Social; week 6; how the environment shapes behaviour

What is environmental psychology?

“The discipline that studies the interplay between individuals and the built and natural environment”

(Steg et al., 2013, p. 2)

Psy1001 Vs PSY2001

Psy2001: the influence of the environment of human experiences, behaviour and well-being

PSY1001: The influence of individuals on the environment- e.g., understanding and promoting sustainable behaviour

The emerging discipline of environmental psychology

Examples of how the (built) environment can shape behaviour:

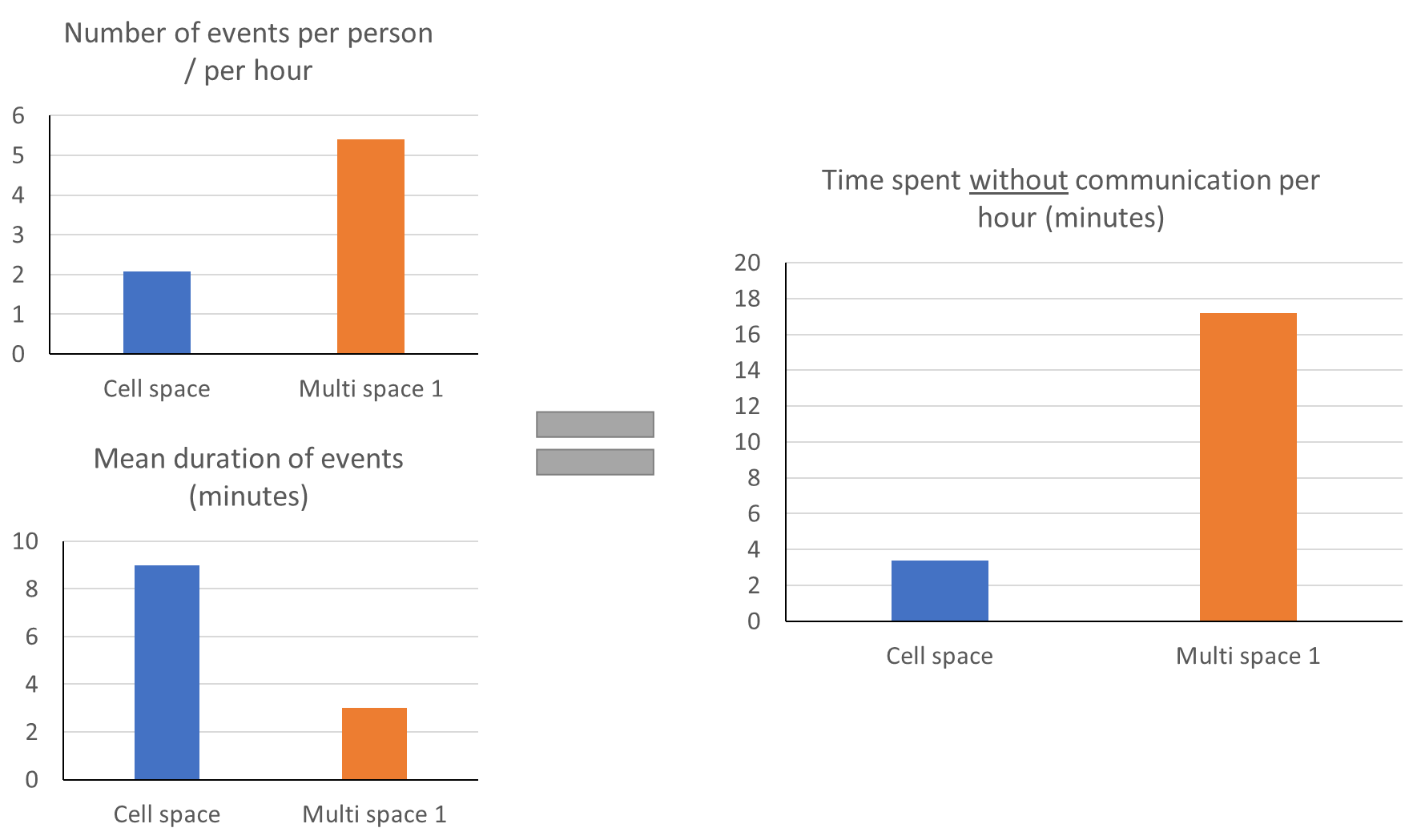

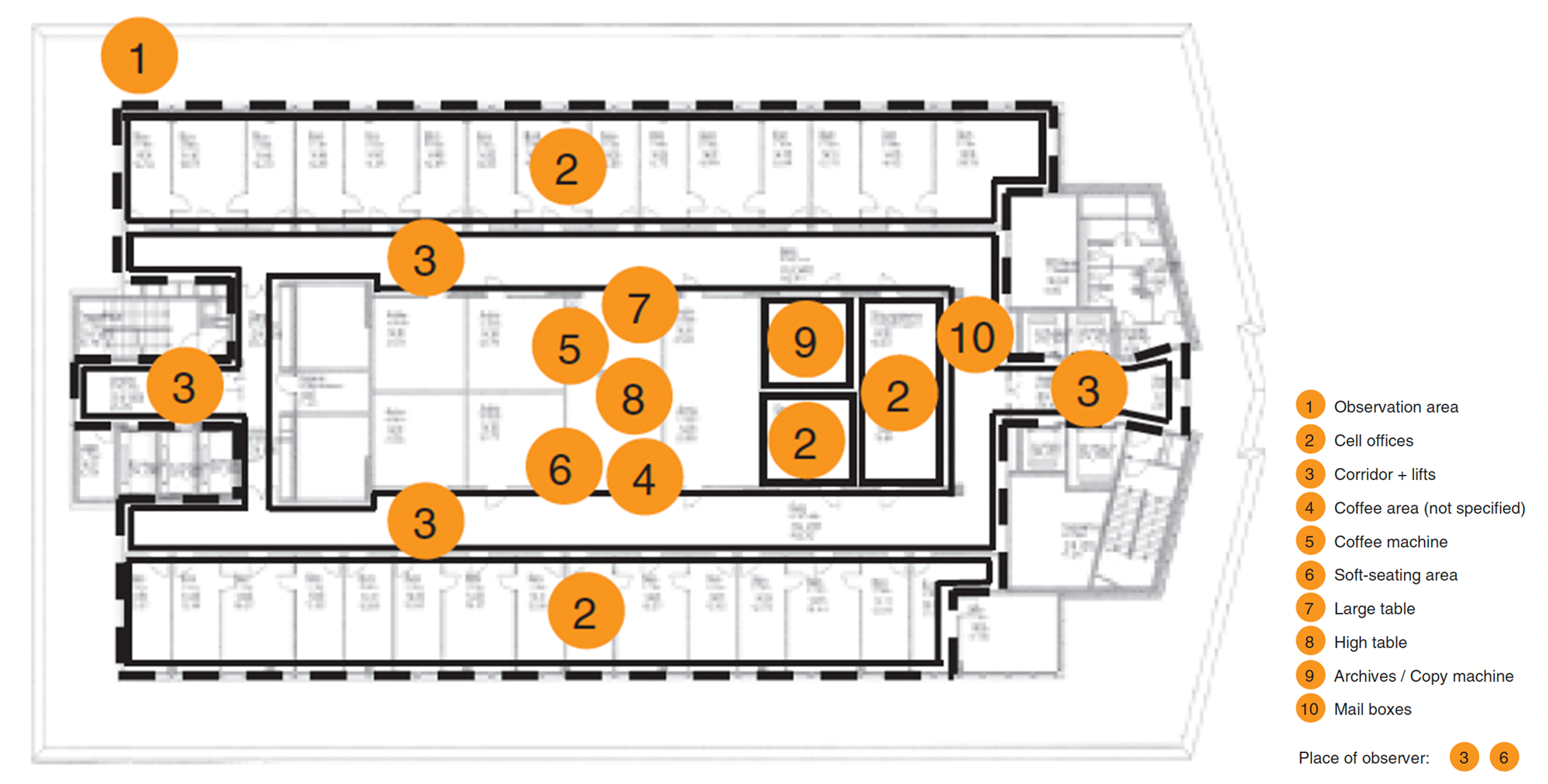

Boutellier et al. (2008)

studied the effect of office layout…

cell offices Vs multi-space layout (x2)

…on communication…

frequency of face-to-face communication

average duration of each event

assess via observation

…in Novartis Campus in Basel, Switzerland

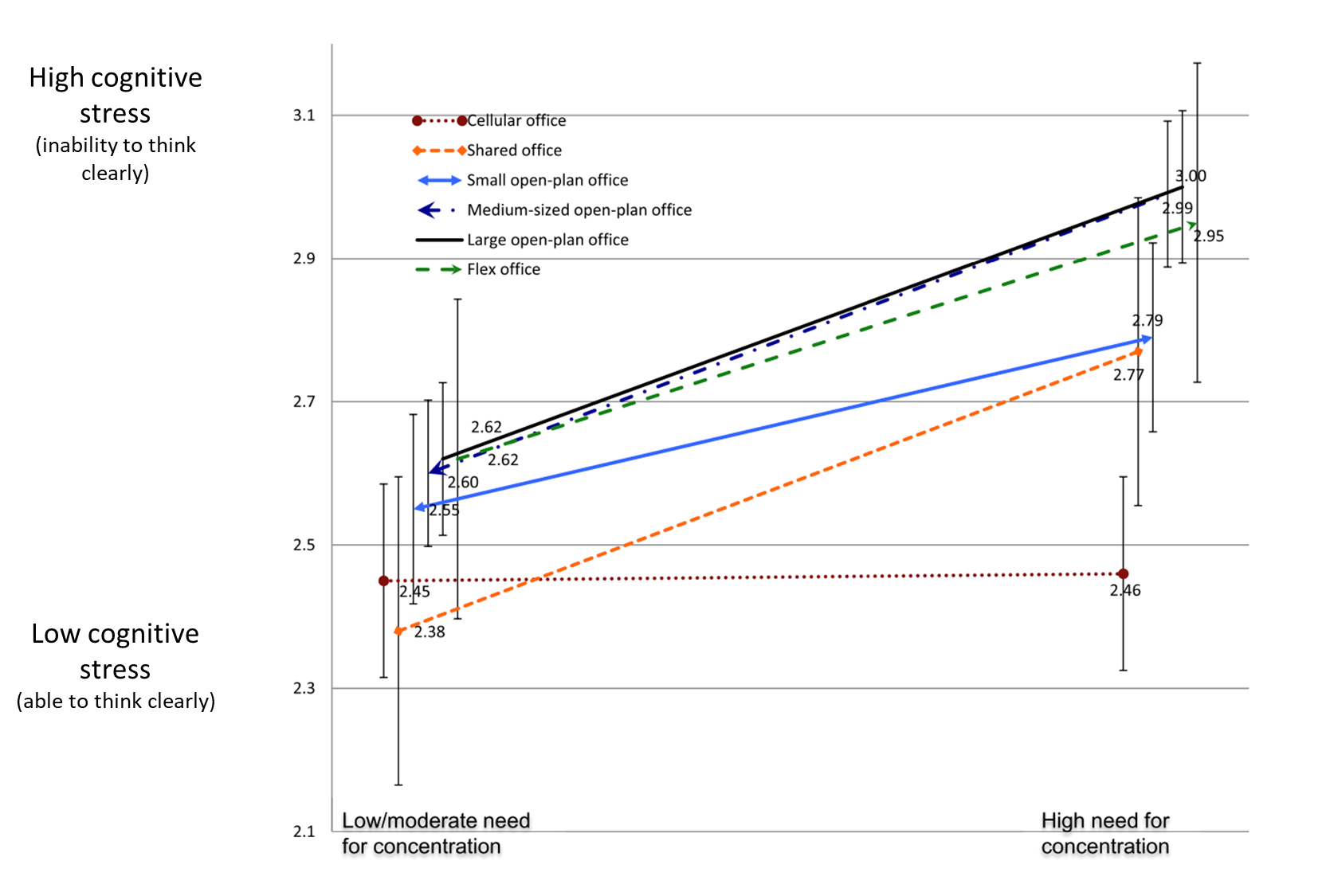

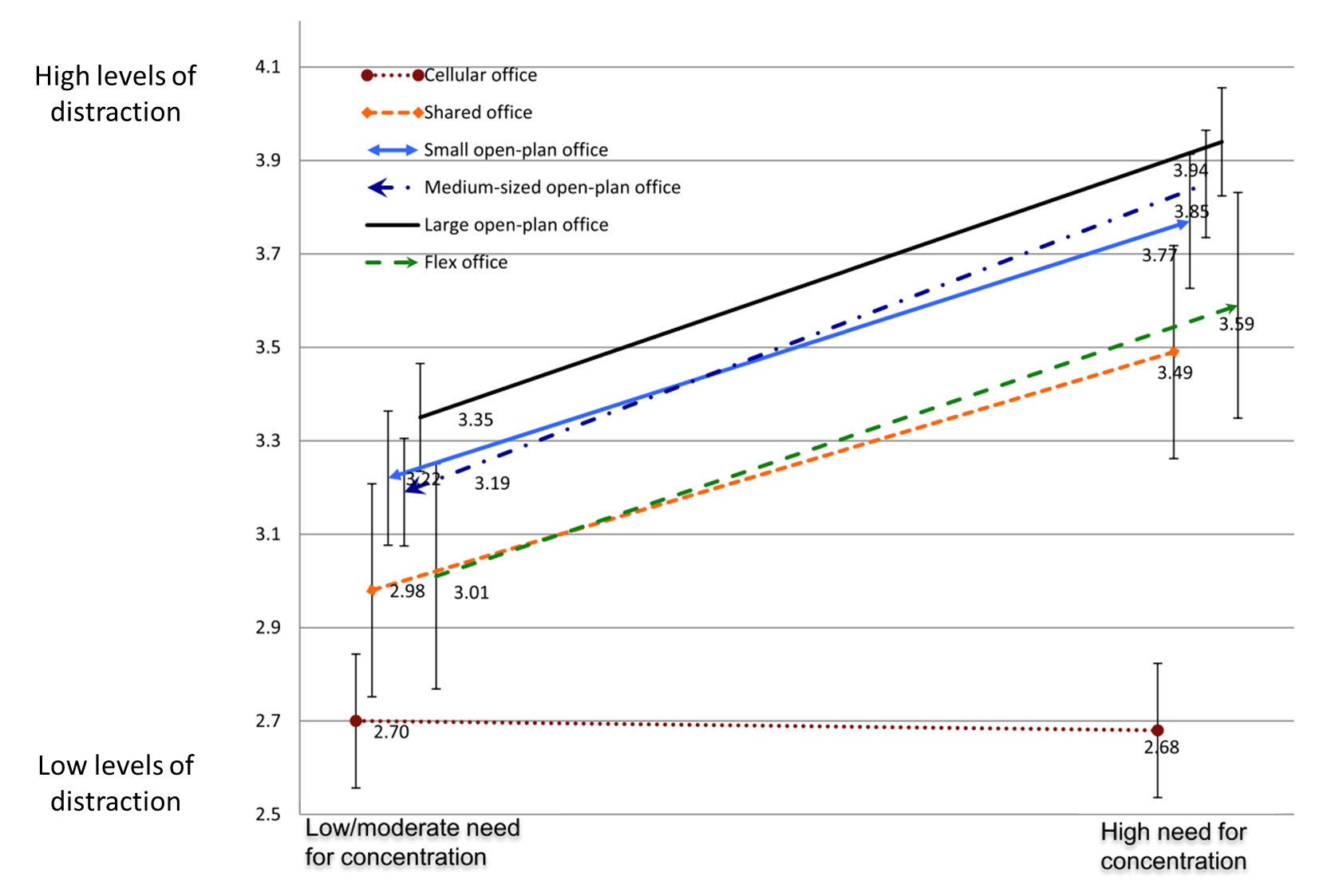

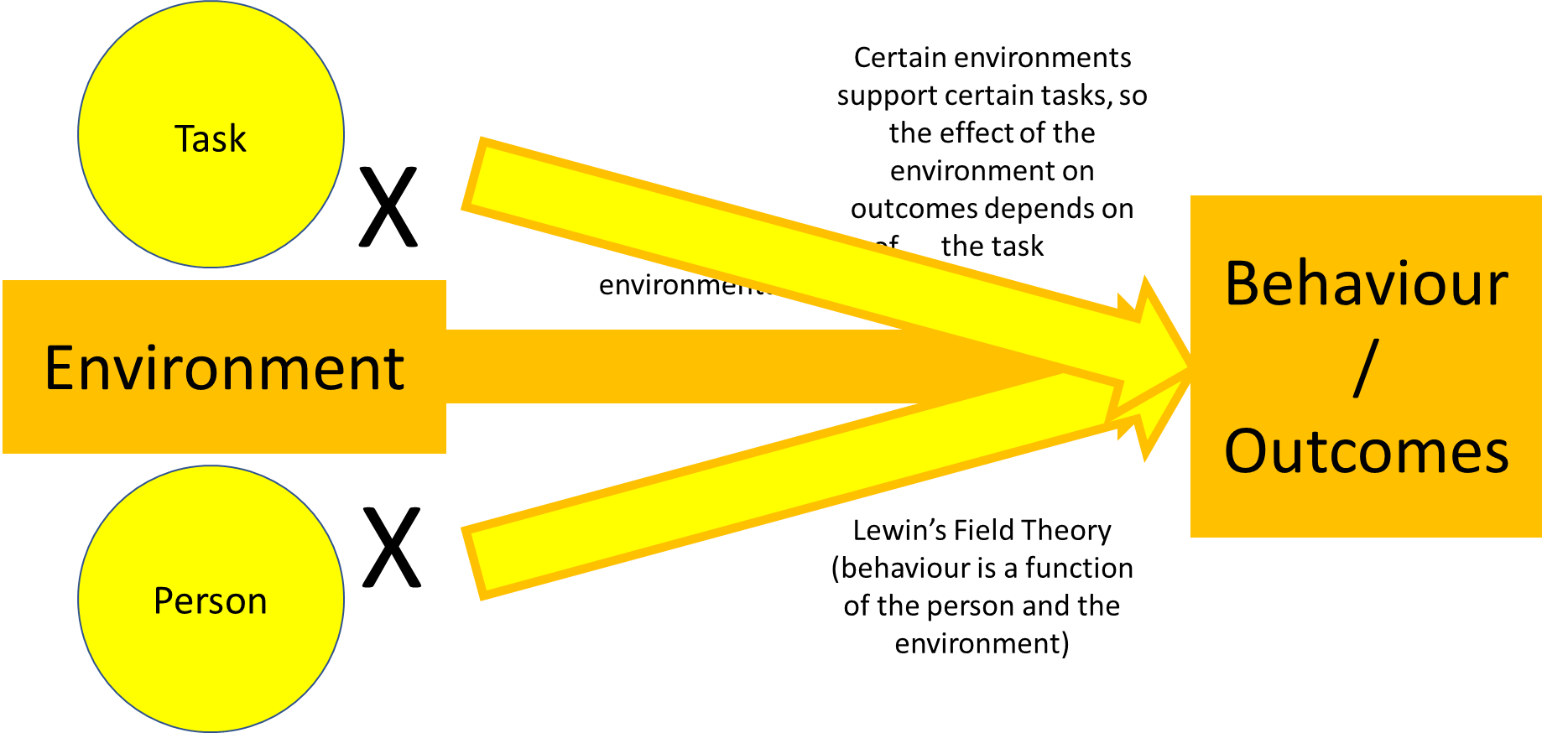

Effect of the environment depends on the nature of the task

Seddigh et al (2014)

independent variables

Office type

cell or individual offices

shared-room offices

small open-plan offices

medium-sized open-plan offices

large open-plan offices

flex offices

Type of task

to what extent do you have individual tasks that require concentration?

dependent variables

distraction

how often are you for some reason disturbed so that you do not get the opportunity to fully immerse yourself in the task you have in front of you

cognitive stress

how much of the time during the past 4 weeks have you found it difficult to think clearly?

Effect of the environment depends on the nature of the person

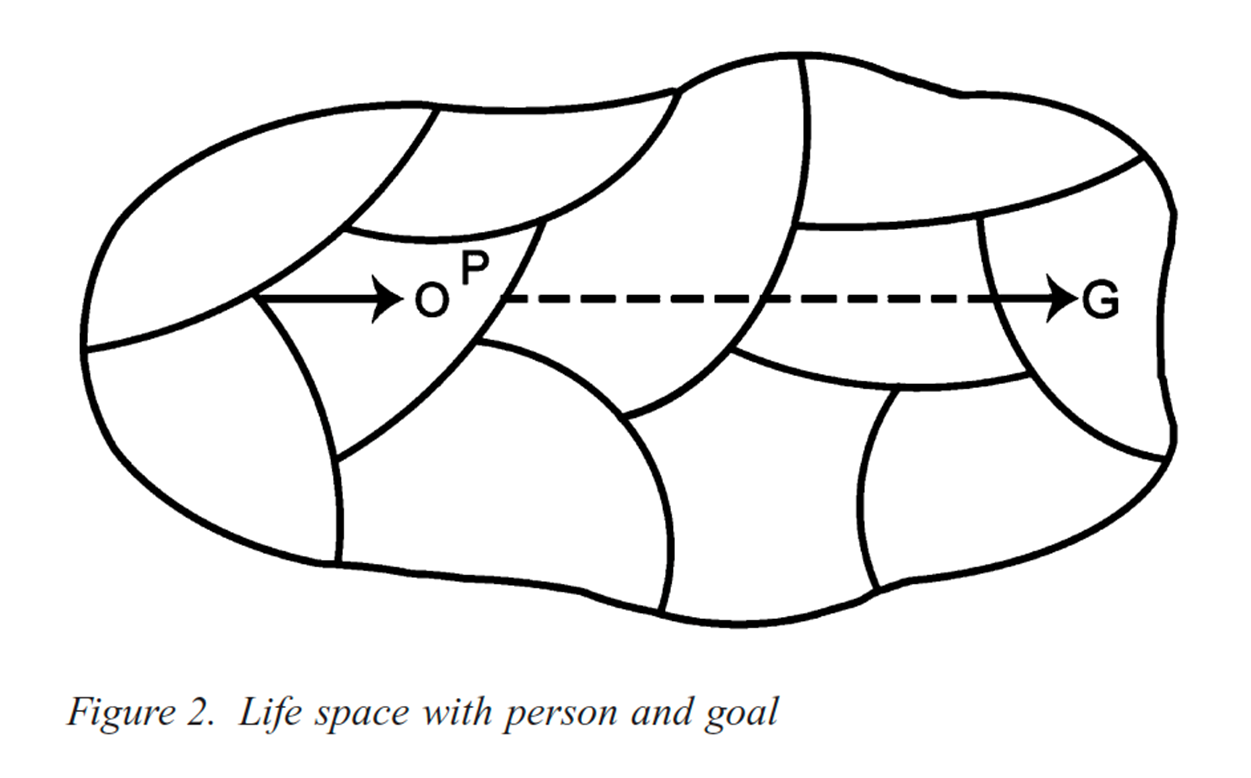

Field Theory (Lewin, 1940)

behaviour is determined by the interaction between a person and their environment

Lewin’s Equation: •: 𝐵 = 𝑓(𝑃, 𝐸)

where 𝐵 is behaviour, 𝑃 is person, and 𝐸 is the environment, f(P, E) is the ‘life space’

Using topology to map the ‘life space’

P is the individual

O represents their current situation or behaviour

G is the goal that they wish to achieve

Environmental response Inventory

McKechnie (1974)

includes need for privacy

there are often times when I need complete silence

I am happiest when I am alone

I get annoyed when people drop by without warning

I am easily distracted by people moving about

Gifford (1980)

Found negative correlations between need for privacy and evaluations of a cafe (r=-0.22) and city hall (r=-0.17)

Roskams et al. (2019)

characteristics of the task

task complexity

interactivity

characteristics of the person

the Big Five Mini-Markers Extraversion Sub-scale

Weinstein’s (1978) Noise sensitivity scale

outcomes

acoustic cimpfrt

disturbances by speech

difficulties in concentration

perceived stress

work engagement

office productivity

“Participants with higher noise sensitivity tended to rate the acoustical quality of the office more negatively, were more disturbed by speech, had greater difficulties in concentration, were more stressed, and had lower self-rated productivity ….

Thus, it can be concluded that the appropriateness of open-plan office for effective work performance is largely moderated by an individual’s noise sensitivity.”

Summary of Part 1:

Certain environments support certain tasks, so the effect of the environment on outcomes depends on the task

environmental psychology

Lewin’s Field Theory (behaviour is a function of the person and the environment)

What makes an environment ‘restorative’?

Perceived Restorativeness Scale (Hartig et al., 1996; 1997)

Fascination

My attention is drawn to many interesting things.

Being Away

Spending time here gives me a good break from my day-to-day routine.

Coherence (Extent)

There is too much going on.

Compatibility

I can do things I like here.

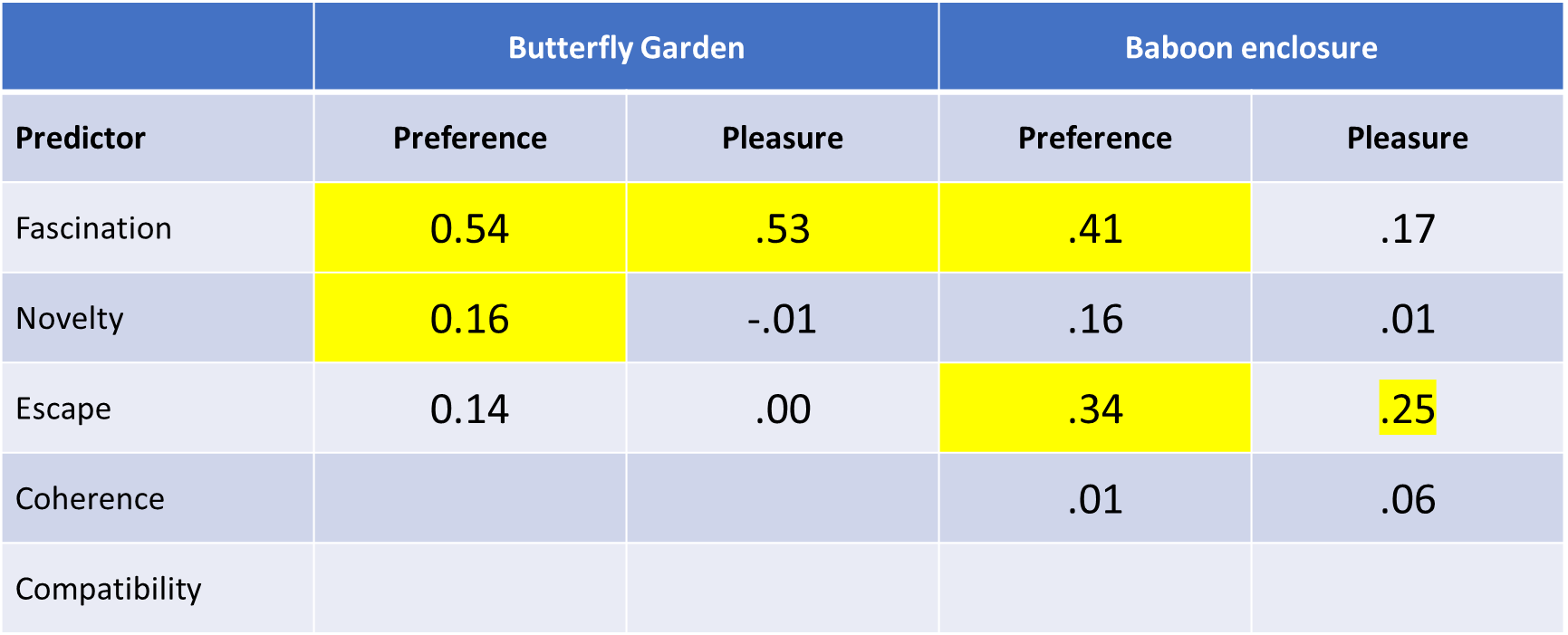

What aspects of zoo attractions make them restorative?

looked at the butterfly gardens Vs the baboons enclosure

an environment doesn’t need to possess all of the features and all aspects to be restorative, just specific parts

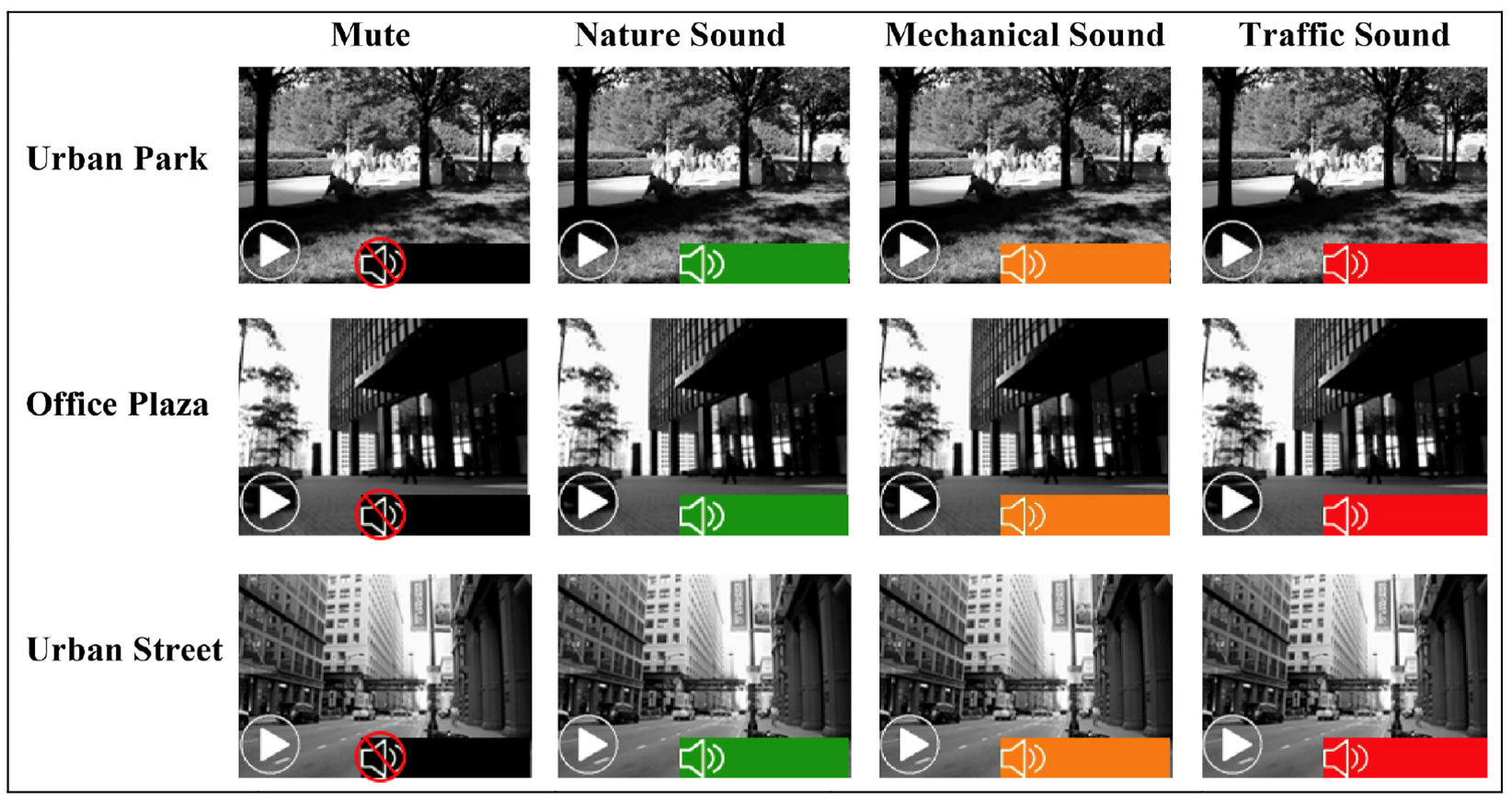

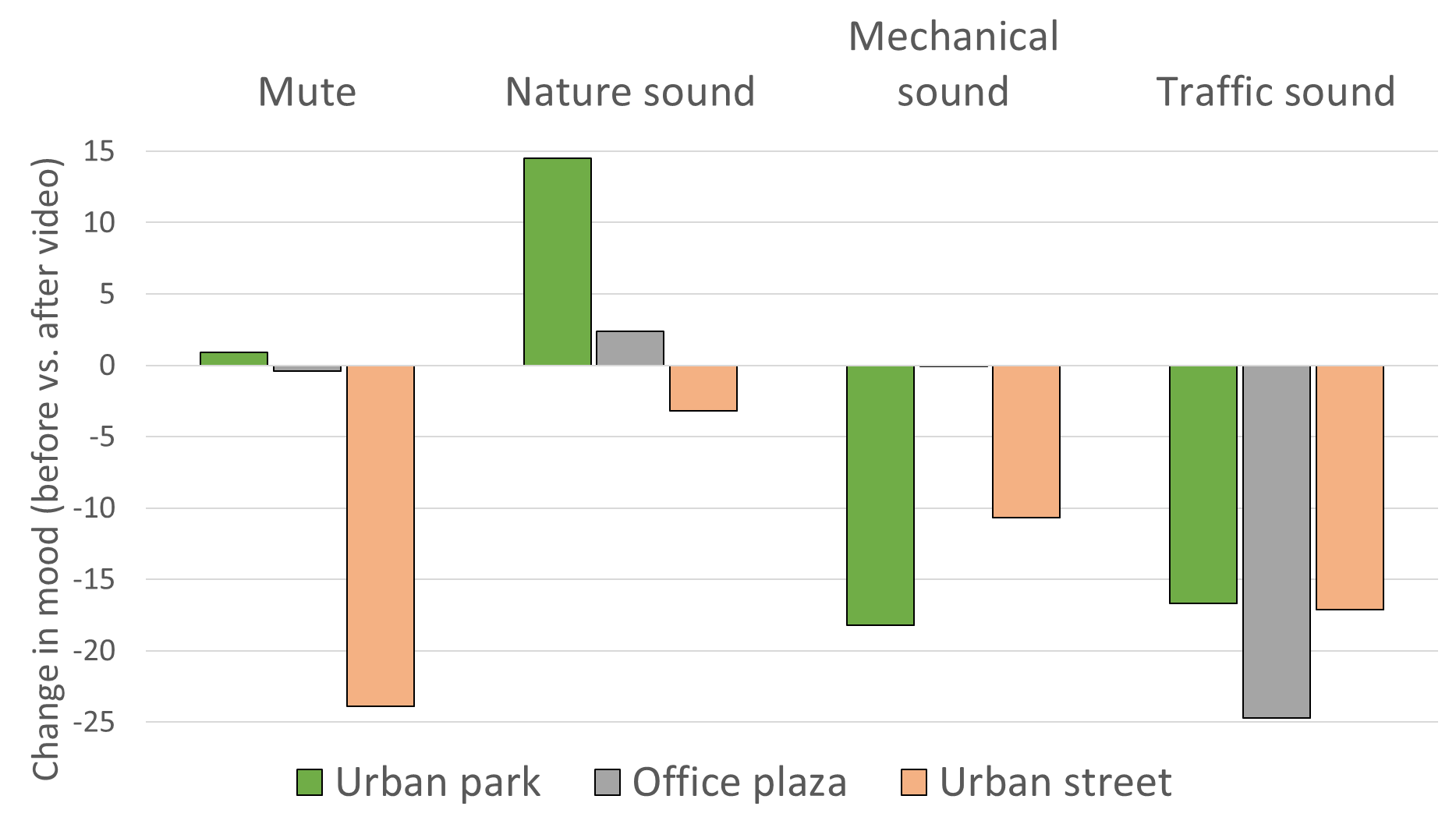

Jiang et al (2021)

They play videos with sounds in headphones of different environments

they could alter noise to make it less or more compatible with vision, so could play nature sounds when looking at an office environment

so is it the visual or auditory aspect more significant and what happens when they aren’t compatible with one another

found that when you play nature sounds with nature visuals increases mood, however, when paired with an urban environment decreased mood

the acoustic environment seemed to have a bigger impact than the visual environment

we like quiet places

Strengths and weaknesses of Jiang et al’s research:

low environmental and external validity

artificial setting, so needs to be replicated in a more real-life situation

What effect(s) do ‘restorative environments have?

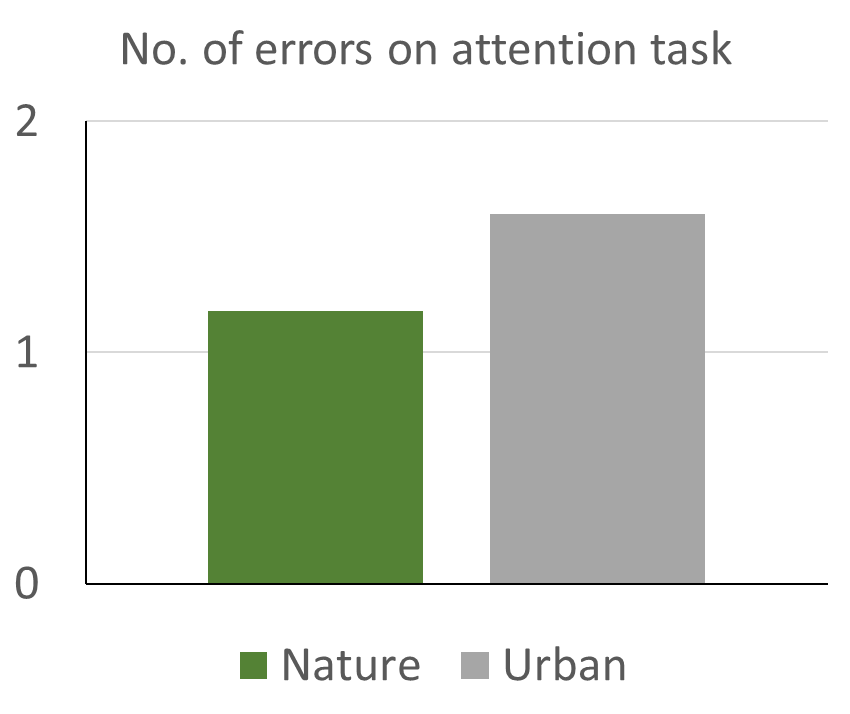

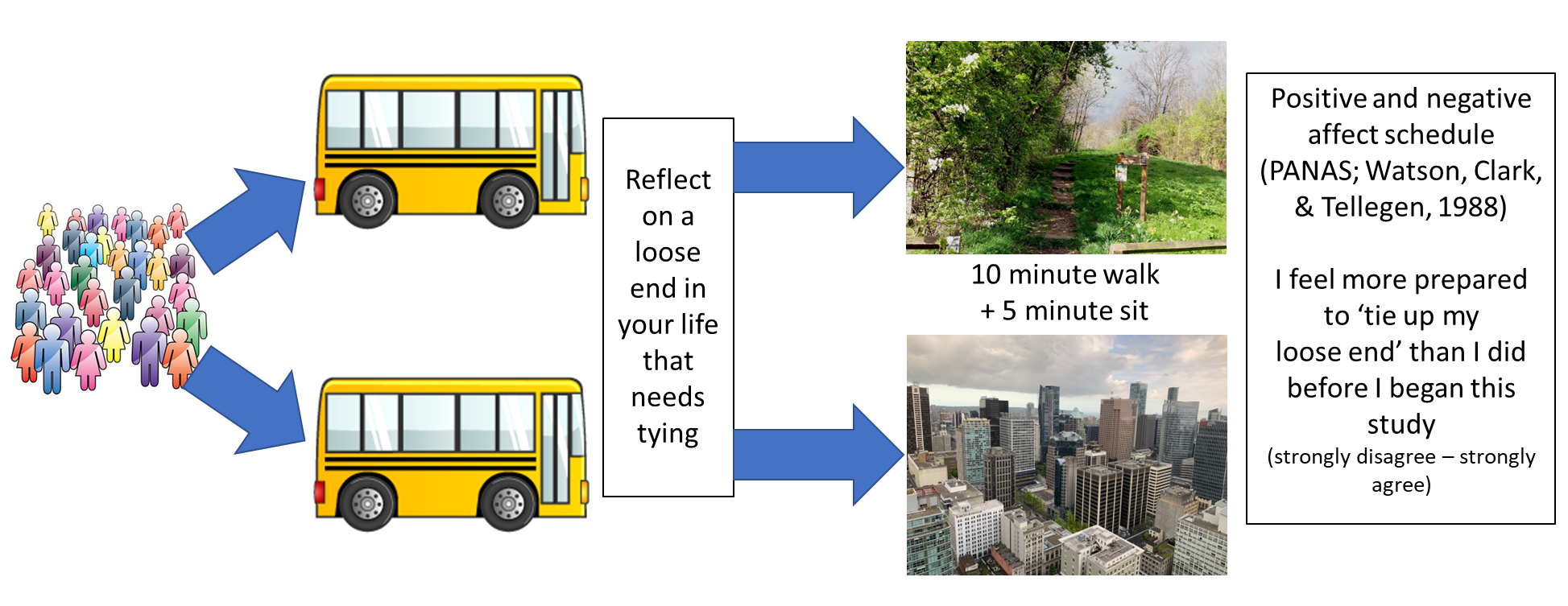

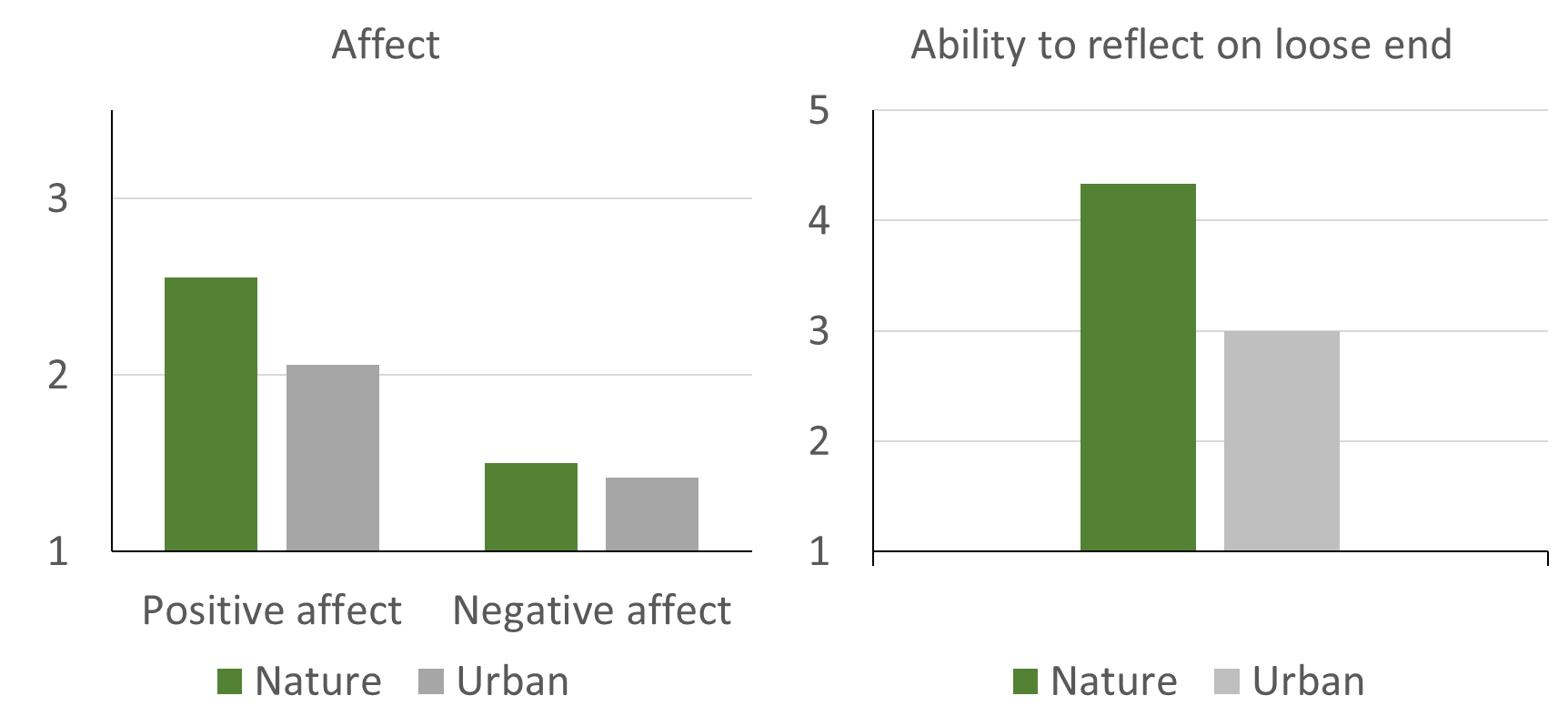

Mayer et al (2009, study 1)

He recruited and randomly allocated pps to board one of two buses

the first bus went to a nature reserve and the second to a busy urban city

whilst on the bus they were asked to reflect on a loose end in their lives that needs tying, it could be romantic, academic, familial etc

Once in their chosen environment they had to either go on a 10 minute walk (nature reserve) or a 5 minute sit (city), then asked about their feelings surrounding the loose end

being in the nature helped them reflect better even if they had no past connection to the area

Soga & Gaston

does spending time in (natural) restorative environments lead people to engage in more pro-biodiversity and pro-environmental behaviour?

Systematic review including 52 effect sizes from 12 case studies

Direct experiences with nature were positively correlated (r+ = 0.20) with actions undertaken with the intention of reducing environmental harms and promoting the protection of the natural environment

quite clear that natural environments are restorative

SHU and SU on restorative natural environments

We depend on nature in every aspect of our lives - it underpins our economy, health and society - and yet progress to restore our wildlife and habitats has been too slow. Ruth’s extensive knowledge and expertise will be vital to help us deliver on our commitments to put nature on the road to recovery.

[Environment Secretary Steve Reed]

Summary of part 2

environments that are fascinating, novel, provide escape and support desired activities are restorative

How do restorative environments exert these effects? (mechanisms)

Stress Recovery Theory

Features in natural environments (immediately) evoke positive affect, without conscious recognition

This serves to lower arousal and reduce stress.

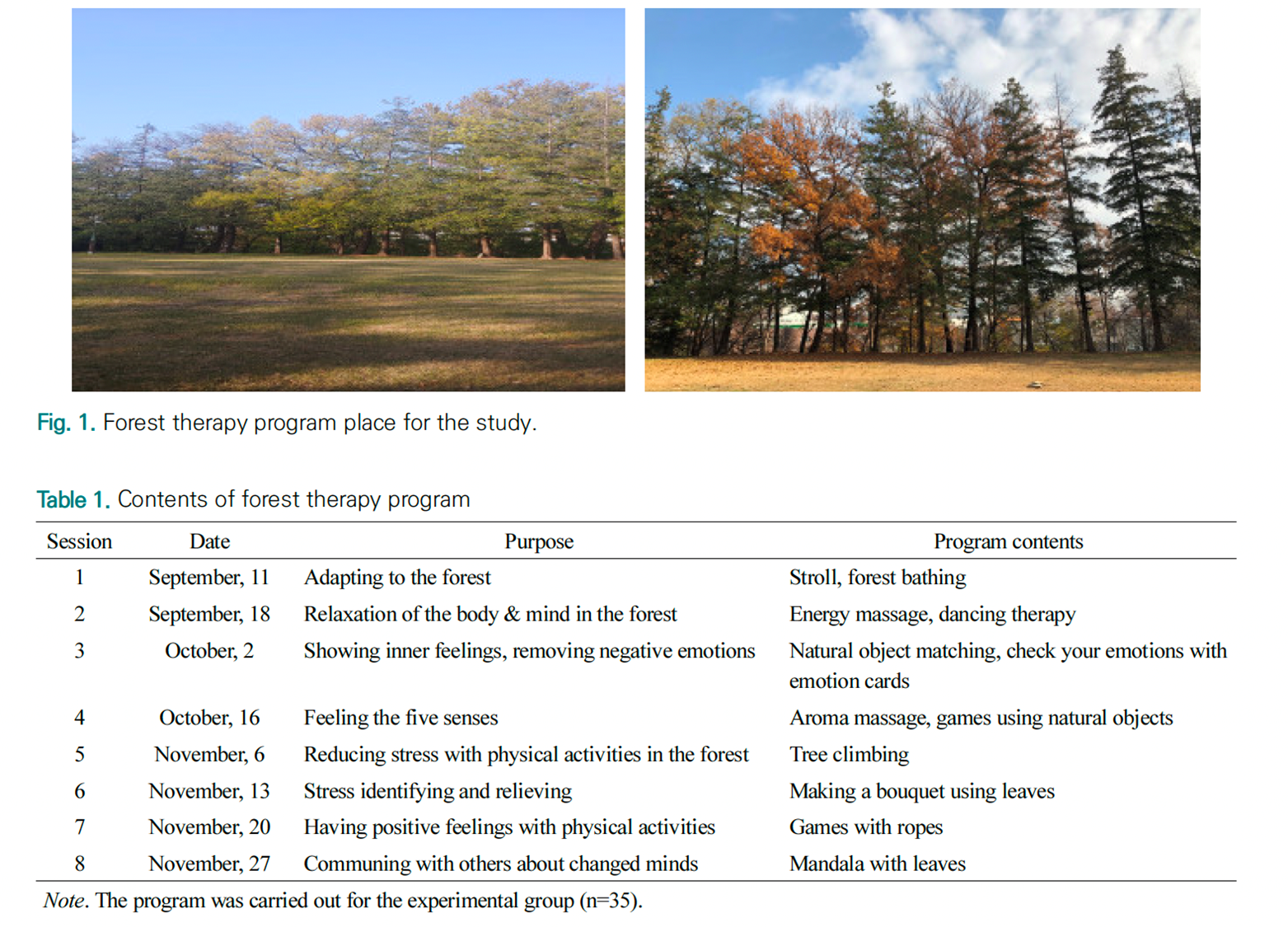

Kang & Shin (2020)

Attention Restoration theory

Kaplan & Kaplan (1989)

Most environments ‘fight’ for our attention and so are depleting.

Termed ‘directed attentional fatigue’

However, natural environments:

Provide fascination

A sense of connectedness

A sense of being away from daily hassles

Are compatible with inclinations

As a result, natural environments restore attention

Mayer et al (2009, study 1)

However, changes in how connected participants felt to nature (not attentional capacity) mediated the effect of exposure to natural vs. urban environments on outcomes

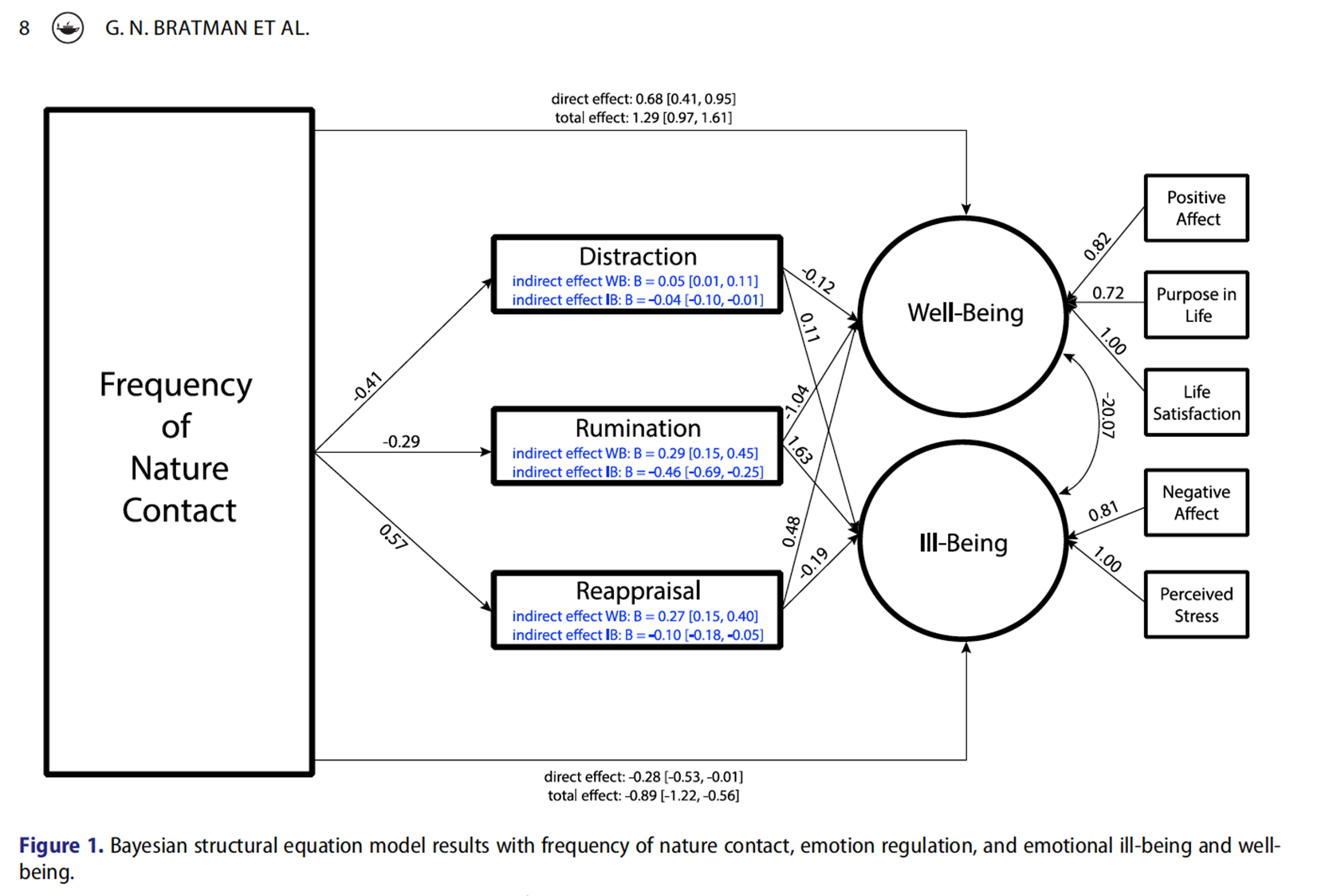

Contact with nature helps people regulate emotions?

Bratman et al (2024) - Survey of 600 adults in the US

Frequency of contact with nature

About how often do you usually visit or pass through outdoor natural areas for any reason?

Use of distraction

To feel less upset during upsetting situations, I divert my attention away from what is happening

Rumination

“I think ‘Why do I have problems other people don’t have?’”

Use of reappraisal

“When something upsetting happens, to feel less upset, I think about the possible benefits of the situation”

Emotional ill-being and well-being

Measures of positive and negative affect, life satisfaction, purpose in life, and perceived stress

Perceptual Fluency Account

Joye et al. (2016)

Natural environments are processed more fluently than urban settings, due to their fractal patterns, which mean that they contain more redundant information than urban scenes

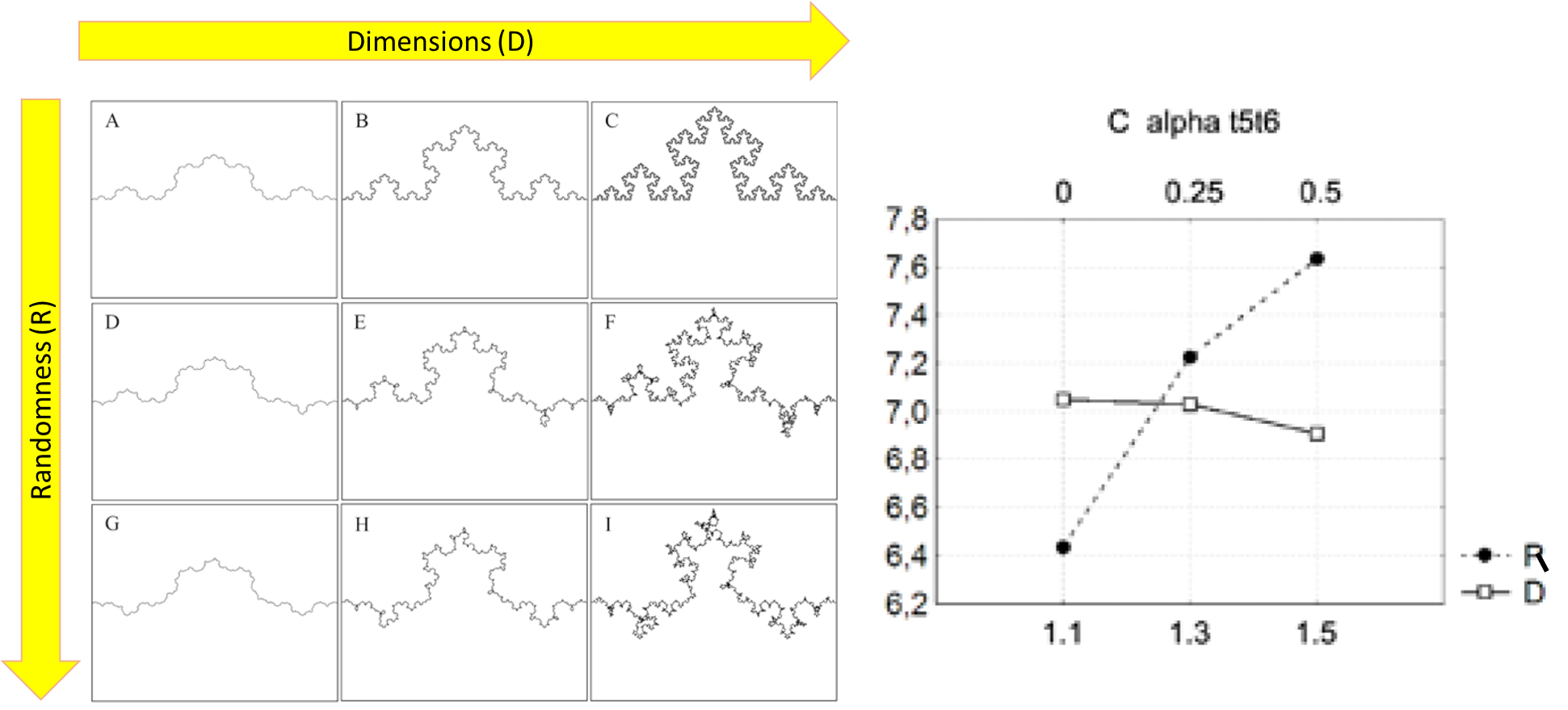

Hagerhall et al (2015)

these are regarding fractals

they used EEG to measure the brain’s responses to various images, these create fractals

the responses could be characterised by the complexity of the environment possibly

for the alpha responses we want high scores on the y axis as this illustrates that we are awake and paying attention

what truly influences are responses is how random these fractals are, rather than the dimensions, as demonstrated by the alpha graph

random fractals are easier to process,

this could support attention restoration theory because our attention has lead to higher alpha scores

Summary of part 3

Why are environmennts restorative

Stress Recovery Theory

Attention Restoration Theory

Perceptual Fluency Account

Core reading: •Steg, L., & de Groot, J. I. M. Environmental psychology: An introduction. BPS Wiley.

•Chapter 6 on ‘Restorative environments’ (by Yannick Joye and Agnes E. van den Berg)

Introduction

What would you recommend to a friend who is feeling stressed and worried? Go to sleep? See a funny movie? Or take a walk in the forest? Chances are high that you will pick the latter option. Indeed, going into nature is probably among the most widely practiced ways of obtaining relief from stress and fatigue in modern Western societies. How can this be explained? More than 150 years ago, the Ameri can landscape architect Frederik Law Olmsted already noted that ‘scenery worked by an unconscious process to produce relaxing and “unbending” of faculties made tense by the strain, noise and artificial surroundings of urban life’ (Beveridge, 1977, p. 40). This analysis seems strikingly modern and prefigures recent theoretical formulations concerning the so-called ‘restorative’ or stress-relieving effects of nature.

6.2 restorative environments research

The word restoration is an umbrella term that, within environmental psychology, refers to the experience of a psychological and/or physiological recovery process that is triggered by particular environments and environmental configurations, i.e. restorative environments. A substantial number of experiments have shown that natural environments tend to be more restorative than urban or built environments. Exposure to restorative natural environments may contribute to well-being and the prevention of disease and illness. As such, restorative environments are a prominent topic in the study of health benefits of nature. All rights reserved. Research into restorative environments has primarily been guided by two theoretical explanations, each with its own interpretation of the construct of restoration. First, stress recovery theory is concerned with restoration from the stress which occurs when an individual is confronted with a situation that is perceived as demanding or threatening to well-being. Second, attention restoration theory focuses on the restoration from attentional fatigue that occurs after prolonged engagement in tasks that are mentally fatiguing. Although there has been discussion on the compatibility of SRT and ART, the two theories are generally regarded as complementary perspectives that focus on different aspects of the restor ative process. In the sections that follow the two theories are explained in more detail.

The experimental paradigm in restorative environments research

Restorative effects of natural and urban environments are typically studied in an experimental paradigm. In this paradigm, healthy volunteers first receive a stress or fatigue induction treatment (e.g. watching a scary movie; performing mentally fatiguing tasks). Next, they are randomly exposed to real or simulated natural versus built environments. Stress and/or mental fatigue are measured at (at least) three points in time: at the start of the experiment (Time 1), after the stress-induction (Time 2), and after exposure to the natural or built environment (Time 3). Changes from Time 1 to Time 2 indicate the effectiveness of the stress induction, while changes from Time 2 to Time 3 indicate the restorative effect of the environment. The three main categories of dependent measures used in restorative environments research are:

affective measures (e.g. how happy/ sad/ stressed do you feel at this moment?)

cognitive measures (e.g. attention and memory tasks)

physiological measures (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, skin conductance, cortisol levels)

These experiments demonstrate that stressed and/or fatigued individuals who are exposed to scenes dominated by natural content have more positive mood changes, perform better on attention tasks and display more pronounced changes characteristic of physiological stress recovery than stressed individuals who are exposed to scenes dominated by built content. These restorative effects have been found for all kinds of natural environments including forests, rural scenery, waves on the beach and golf courses.

Stress recovery theory

Roger Ulrich laid the foundations for SRT in the 1983 article ‘Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment’. Based on the work of Zajonc (1980), he argued that people’s initial response towards an environment is one of generalised affect (i.e. like, dislike), which occurs without conscious recognition or processing of the environment. Initial positive affective responses come about when specific environ mental features or preferenda are present in the environment. These features include the presence of natural content (e.g. vegetation) as well as more structural features such as complexity, gross structural features (e.g. symmetries), depth/spatiality cues, an even ground surface texture, deflected vista (e.g. a path bending away) and absence of threats. Quick positive affective responses to these features initiate the restorative process because they provide a breather from stress, accompanied by liking and reduced levels of arousal and negative feelings such as fear. If the scene draws enough interest, more conscious cognitive processing of the environment may take place, which may result in a more conscious and deliberative restorative experience.

attention restoration theory

While SRT considers restoration as a quick, affect-driven process, ART emphasises the importance of slower, cognitive mechanisms in restoration. ART was fully described for the first time in 1989 by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan in the book The experience of nature. In this book, the Kaplans provide a broad overview of their long-term research on people’s relationship with nature, which encompasses not only restorative experiences but also perceptions and visual preferences. In the latter domain, Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) are well known for their ‘preference matrix’, a framework for predicting people’s landscape preferences (see Chapter 4 for a detailed discussion of this model). The preference matrix is sometimes con fused with ART, because both models consist of four components and were devel oped by the same authors. However, the preference matrix and ART should be considered as distinct models, each focusing on different aspects of the people nature relationship. Copyright © 2012. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. All rights reserved. A core assumption of ART is that people only have a limited capacity to direct their attention to something that is not in itself interesting. The cognitive mechanism necessary to inhibit or block out competing stimuli, called the central executive, becomes depleted with prolonged or intensive use (Kaplan & Berman, 2010). Depletion of this central executive mechanism can result in directed atten tional fatigue (DAF). ART predicts that environments can counter DAF when the human-environment relationship is characterised by four qualities: fascination or the capacity of an environment to automatically draw attention without cognitive effort, a sense of extent or connectedness, being away from daily hassles and obliga tions, and a compatibility between the individual’s inclinations and the characteristics of the environment (see also Box 6.2). Because the combination of these four quali ties is most typical for human interactions with natural environments, these envi ronments tend to be far more effective in countering DAF than most built settings. However, restorative experiences are also possible in other settings, such as monasteries or museums

Perceived restorativeness

lots of research measures actual changes in people’s restorative state after exposure to environments

a second line of research has focused on measuring the perceived restorative potential of environments

most studies use the perceived restorative scale or a variation of it

The PRS consists of statements that tap the four restorative characteristics described by AR. For each statement, respondents are asked to indicate on a likert-type scale the extent to which the statements fits their experience of a given environment

sample items like:

‘my attention is drawn to many interesting things (fascination)’

‘there is much going on here’ (extent/ coherence)

‘spending time here gives me a break from my day-to-day routine’ (being away)

‘I can do things I like here’ (compatibility)

A recurrent finding is that natural environments tend to be perceived as more restorative than built environments. The scale has been successfully used to evaluate the restorativeness of landscape designs and zoo attractions

The evolutionary origins of restorative nature experiences

Restorative responses are often interpreted as relics of human evolution in a natural world. Specifically, it has been proposed that certain natural features (e.g. verdant vegetation) and particular natural landscapes (e.g. savannahs) could offer ancestral humans resource opportunities and safety (e.g. trees as shelters), and in so doing, promoted human survival. Consequently, humans may have developed a biologically prepared readiness to display positive affective responses to such elements. Although widely held in the field of restorative environments research, this evo lutionary account has been put into question. One empirical criticism is that the already few studies on restoration are often performed with undergraduate students in Western countries. The results obtained with such a limited group can hardly provide any justification for the evo lutionary, universalist assumptions underlying restoration theories. A more concep tual problem is that the human species has always inhabited more or less vegetated environments during its evolutionary history. Because this implies that greenery has always been available to everybody, it is unclear why there would have been any selection pressure for evolving preferences for these elements, as restoration theories seem to imply.

Recent theoretical and empirical developments:

perceptual fluency account:

The perceptual fluency account (PFA) is based on the phenomenon of perceptual fluency and aims to provide an integration of both SRT and ART. The central assumption of PFA is that natural environments are processed more fluently than urban settings, and this fluency difference leads to a difference in restorative potential. Perceptually fluent processing of natural stimuli and scenes is thought to occur because the visual brain is more tuned in to the way in which visual information is structured in natural scenes than in built environ ments. Specifically, it is thought that owing to their so-called fractal or self-similar patterns, natural scenes contain much more redundant information than urban scenes, probably making the former more fluent to process than the latter. Within the PFA, the greater stress-reducing capacity of nature, as predicted by SRT, may be explained by the greater safety or familiarity commonly associated with fluent versus disfluent stimulus organisations. The greater attention-restoring potential of natural environments, as predicted by ART, may be explained by the fact that fluent stimuli are lower on cognitive resource demands than disfluent ones, which leaves more place for replenishing attentional resources.

connectedness to nature:

Another recent theoretical approach to restoration starts from the observation that people gain purpose and meaning in life by feeling that they belong to the natural world. Based on this, it is predicted that feeling emotionally connected to nature is an important mechanism underlying beneficial effects of nature. In a series of experiments, Mayer, et al (2009) established that the positive effects of exposure to nature on positive affect and the ability to reflect on an unresolved life-problem could partially be explained by increases in connectedness to nature. Exposure to nature also increased attentional capacity, but this could not explain participants’ greater positive feelings and ability to reflect. These findings provide some of the first empirical evidence for the supposition that an experiential sense of belonging to the natural world plays a role in restorative environment experiences, besides more unconscious, automatic processes.

Micro-restorative experiences and instorative effects

A third approach has focused on micro-restorative experiences that result from brief sensory contact with nature, as through a window, in a book, on television or in a painting (Kaplan, 2001). Accumulated over time, such micro-restorative experiences may significantly improve people’s sense of well-being and provide a buffer against the negative impacts of stressful events. A survey on nature-based coping strategies of elementary school teachers suggests that micro-restorative experiences are espe cially helpful when stress levels are low. Teachers who frequently suffered from vocational stress (having to teach in overcrowded classrooms, poor working conditions) preferred to go out and be in nature (such as taking a walk in the woods), whereas those with low levels of vocational stress found sufficient merit Consistent with these findings, there is increasing evidence that exposure to nature may not only have restorative, but also instorative effects in individuals who are not stressed or fatigued (Hartig, 2007). Recent studies among healthy, unstressed indi viduals have shown that exposure to nature may improve people’s mood states and ability to reflect (Mayer et al., 2009), and increase subjective ‘vitality’ or energy levels.

6.5 applications and implications

Findings from restorative environments research are increasingly being used to guide the design and management of natural and built environments. Given its emphasis on recovery, restorative design measures appear to be most suited for contexts in which stress and attentional fatigue are relatively acute and where such states hamper healing or developmental processes. This is probably one of the reasons why restora tive elements have become an essential part of so-called evidence-based design (EBD) of healthcare settings. However, as certain aspects of urban living constitute a significant and prolonged source of stress, a number of scholars have argued for integrating nature-based design measures on the scale of entire urban environments. In particu lar, the findings on the micro-restorative and instorative effects of nature show that even in unstressed urbanites, green interventions may still have a vitalising role and improve the appeal of the environmental context. One challenge for applying restorative design measures involves the optimal amount of exposure to nature. As discussed above, the available evidence suggests that one does not need to be deeply immersed in a vast natural environment to experience restoration. On the other hand, there are indications that ‘more is better’, especially in urban areas with little green space. However, for some natural elements such as water there appears to be an upper limit to the amount that is effective for restoration. More research is needed to provide more detailed, evidence-based guidelines for designing optimal restorative environments for different groups, contexts and activities. Another question relevant to nature-based interventions is which modality of nature needs to be implemented. Research shows that exposure not only to actual nature, but also to visual simulations (e.g. videos, paintings) and to olfactory (smells) or auditory components can have restorative effects. Preliminary investigations suggest that restorative responses might even extend to geometric properties of nature, such as the fractal repetition of patterns at many scale levels of natural scenes. This extends the possible scope of restorative design measures from actual nature, to imitations of nature and nature’s fractal geometry in architecture

Summary

There is increasing empirical evidence that contact with nature can provide restoration from stress and mental fatigue. Two theoretical perspectives for the restorative effects of nature have dominated the restorative environments research agenda, namely SRT and ART. While in both viewpoints it is commonly assumed that restorative responses are ancient relics of human evolution in natural environments, that view has become criticised. In recent years, theoretical developments relying on concepts such as ‘fluency’, ‘connectedness to nature’ and ‘micro-restorative experiences’ have aimed to further and deepen our understanding of restorative experiences. The empirical evidence for restorative effects of nature is increasingly applied in healthcare and in urban and landscape planning, but further research is needed to optimize these applications.'

Directed attentional fatigue- A neurological symptom, also referred to as ‘mental fatigue’, which occurs when parts of the central executive brain system become fatigued.

perceptual fluency- The subjective experience of the ease with which a certain stimulus is perceptually processed.

preferenda- Features of a setting or an object that are evaluated very rapidly on the basis of basic sensory information.

fractal- A rough or fragmented geometric shape of which the parts are each (at least approxi mately) reduced-size copies of the whole. Most natural structures are fractal in form.

Micro-restorative experiences- Brief sensory interactions with nature that promote a sense of well-being.

extent- A quality of restorative environments, as described by ART, which is a function of scope and coherence. Scope refers to the scale of the environment, including the immediate surroundings and the areas that are out of sight or imagined. Coherence refers to a degree of relatedness between perceived features or elements in the environment, and the contribution of these elements to a larger whole

being away- A quality of restorative environments, as described by ART, indicating an environment that is free from reminders of daily hassles and obligations that overtax the capacity for directed attention.

compatibility- A quality of restorative environments, as described by ART, indicating a good fit between the individual’s inclinations and the characteristics of the environment, so that no attentional resources need to be devoted to questioning how one should behave or act appropriately.

fascination- A quality of restorative environments, as described by ART, indicating the capacity of an environment to automatically draw one’s attention without cognitive effort, thereby relaxing the demand on the central executive and leaving room for the replenishment of directed attention.

instorative effects- Improvements in psychological and/or physiological functioning that are triggered by particular environments and environmental configurations.