Chapter 7: Elasticity, Microeconomics Policy, and Consumer Theory

Elasticity of demand (ED)

- It’s a measure of the responsiveness of consumers to change in price

- If a firm increases price of their product, would consumers still buy it?

- If a demand for a product is inelastic, change in price wouldn’t impact the consumers much e.g. cancer medicines

- If the demand for a product is elastic, change in price would impact the quantity purchased of that product

- The following is the formula to calculate the ED

- %change in Qd / %change in Price

- Economists ignore the negative value of PED

- The greater the value, the more sensitive consumers are to a change in the price of good X

- The answer that is received falls under the following ranges, each with their own interpretation

| ]]Type of Elasticity]] | ]]Elasticity value]] |

|---|---|

| Perfectly inelastic | 0 |

| Relatively Inelastic | <1 |

| Unit elastic | 1 |

| Relatively elastic | >1 |

| Perfectly elastic | Infinity |

Example

- Suppose the price of designer blue jeans increases from $100 to $120 and the quantity demanded decreases from 10 to 9

- First, calculate the percentage change for both price and quantity demanded: ($120 – $100)/$100 = 0.2= 20% increase in price

- (9 – 10)/10 = –0.1 = 10% decrease in the quantity demanded.

- Ed = (–10%)/(20%) = 0.5

- The price elasticity is relatively inelastic

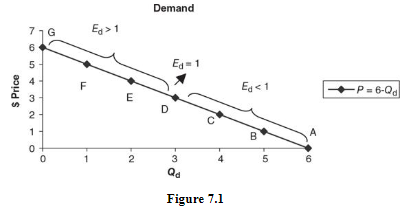

Elasticity on the demand curve

The midpoint formula

- (Change in Qd/Change in Price) x (Average price/ Average quantity)

Example

- Initial price of a hypothetical product is $16, and 20 units are demanded

- The price rises to $20, quantity demanded falls to 10 units.

- The average price between these two points is $18, and the average quantity is 15 units

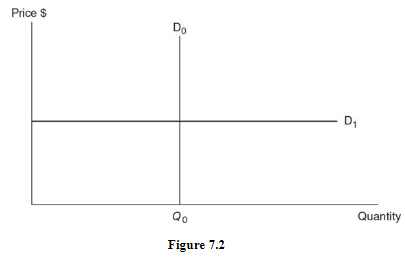

Special cases

- The following is a perfectly inelastic demand curve (D0)

- No substitutes

- Vertical demand curve tells us that no matter what percentage increase, or decrease, in price, the quantity demanded remains the same

- Ed = 0

- The following is a perfectly elastic demand curve (D1)

- Many substitutes

- Horizontal demand curve tells us that even the smallest percentage change in price causes an infinite change in the quantity demanded

- Ed = infinite

- Note: As a demand curve becomes more vertical, the price elasticity falls and consumers become more price inelastic

Determinants of elasticity

- Number of Good Substitutes

- Proportion of Income

- Time

Total revenue test to determine elasticity

- Total revenue is price x quantity

- The answer falls under the following categories, each with its own interpretation

| ]]Type of Elasticity]] | ]]Relationship between Price and total revenue (TR)]] |

|---|---|

| Relatively elastic | inverse relation |

| Relatively inelastic | direct relation |

| Unit elastic | TR doesn’t change when P changes |

- If price increases but total revenue decreases, the demand for the product is relatively elastic

- If price increases and total revenue also increases, the demand for the product is relatively inelastic

- If price changes but total revenue stays same, the demand for the product is unit elastic

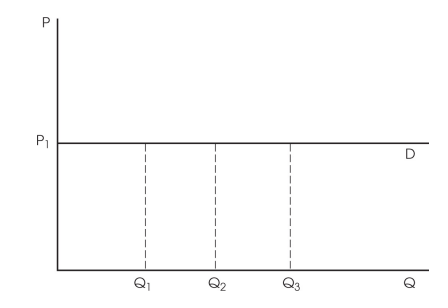

Perfect elasticity

If the demand is perfectly elastic, the price elasticity is infinity

Any price above P1 and the demand falls to zero

Any price that’s exactly P1, the demand could keep increasing (buyers would buy as much quantity as possible)

Any price below P1 and the quantity demanded becomes infinite

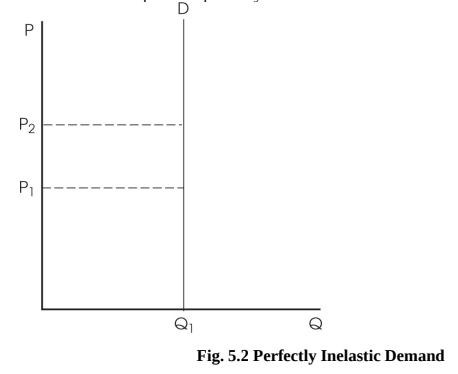

Perfect inelasticity

If the demand is perfectly inelastic, the price elasticity of demand is zero

As the price keeps on changing, the quantity demanded stays same

A good example of this would be life-saving drugs

Prices could increase by a big margin but quantity demanded wouldn’t change still

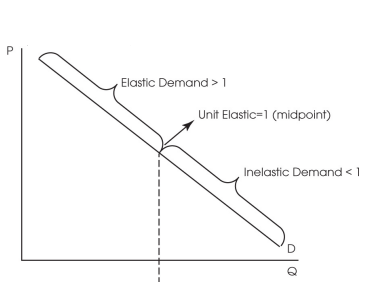

Elasticity along a linear demand curve

- The demand curve is elastic towards the top, unit elastic at the midpoint and inelastic towards the bottom

- As the prices decrease in the elastic range, the total revenue eventually increases

- As the prices decrease in the inelastic range, the total revenue actually decreases

- Monopolies (a type of market structure) prefer producing in the elastic range because that’s also where the revenue is maximized

Income Elasticity of demand

This measure how the demand for a product changes with respect to change in their income

% change in quantity demanded/ %change in consumers income

Calculations of this help determine whether the product is inferior or normal good

Inferior good: as income increases, demand for the product decreases

Normal good: as income increases, demand for the product increases

Three Questions to Determine Demand Elasticity

1. Necessity of the product

- If the product is a necessity, such as life-saving drugs, prices could increase but people would still purchase it

- Products which are wants, such as cars, demand would be price elastic

2. Could the purchase be delayed

- The longer the time consumers have the product as a choice, the more elastic the product demand tends to be

- If the choice time is limited, the product demand tends to be inelastic

- A good example would be emergency supplies

- Since the decision time is limited, demand tends to be inelastic

3. Does the purchase require a larger budget range?

- If the product forms a large proportion of someone’s budget, demand tends to be elastic

- An increase in the price of luxury products would result to consumers stopping their purchase for the time being

- On the contrary, products that don’t form a large proportion of someone’s budget such as match sticks, are inelastic in nature (purchased even if prices increases)

Cross-price elasticity of demand

- This measures how a demand for a product changes with respect to price changes

- Calculations of this help determine whether the product is a complement or substitute

- % change quantity demanded for product X/ % change in price of product Y

- If the result is positive, the product is substitute

- If the result is negative, the product is complement

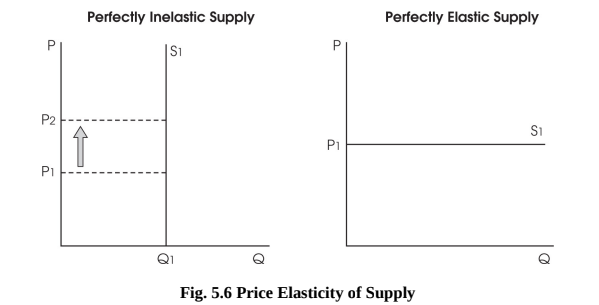

Price Elasticity of supply

This measures the change in supply that takes place with respect to changes in price

Time is key factor when looking at supply elasticity

The longer the firms have time to adjust, the more elastic the supply (difficult to adjust in the short term hence the inelasticity)

In the longer run, market supply is usually perfectly elastic

% change in quantity supplied / % change in price

If the demand curve is perfectly elastic, there wouldn’t be any consumer surplus

If the supply curve is perfectly elastic, there wouldn’t be any producer surplus

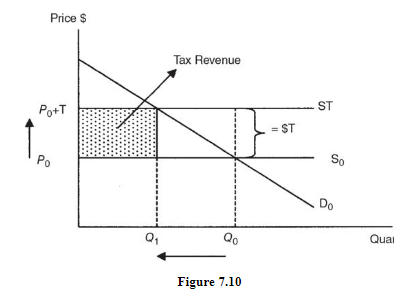

Excise taxes

- Per-unit tax on production

- Firm responds as if the marginal cost of producing each unit has risen by the amount of the tax

- Results in a vertical shift in the supply curve by the amount of the tax

Reason for taxes are:

- Increase revenue collected by the government

- To decrease consumption of a good that might be harmful to some members of society

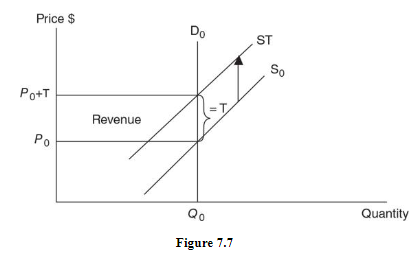

Demand Is Perfectly Inelastic

Assume the following demand is of tobacco

If a per-unit tax of T is imposed on the producers of cigarettes, the supply curve shifts upward by T

Since quantity remained constant, the tax did nothing to decrease the harmful effects of smoking in society

Only increased tax revenues for the government

The entire tax was paid by consumers in the form of a new price exactly equal to the old price plus the tax.

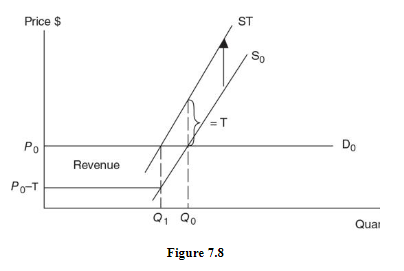

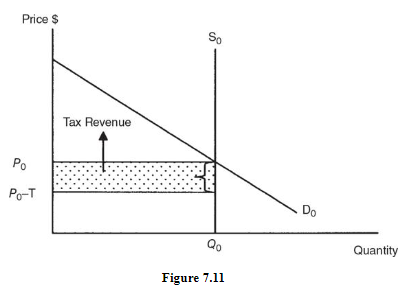

Demand is perfectly elastic

Assume the following demand is of tobacco

The per-unit tax of T shifts the supply curve upward by T

Because the price of a pack of cigarettes did not increase after the tax, it was not the consumers who paid more

Producer pays the entire share of the tax when demand is perfectly elastic

Compared to the perfectly inelastic scenario, the government collected much fewer tax revenue dollars

Maximum decrease in harmful cigarette consumption is a definite plus

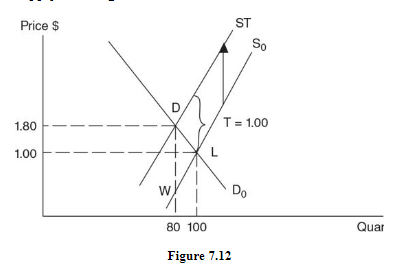

The Role the Supply Curve Plays in the Impact of an Excise Tax

A perfectly elastic, or horizontal, supply curve tells us that even a very small change in the price will cause an infinitely large change in the quantity supplied

The new equilibrium price is exactly T higher than the old price P0, so consumers pay the entire burden of the tax

The equilibrium quantity decreases from Q0 to Q1, and the government collects tax revenue equal to T × Q1.

A perfectly inelastic, or vertical, supply curve illustrates the special case where any change in the price creates absolutely no change in the quantity supplied

At the equilibrium quantity Q0, suppliers would like to charge a higher price than P0, but any price above P0 creates a surplus, and this surplus will clear only at the equilibrium price P0.

The firms must pay T to the government for each of the Q0 units that are sold and consumers continue to pay the original price of P0

Producers pay the entire burden of the tax because, after paying the tax, they receive only (P0 – T) on each unit

Price elasticity of supply and tax incidence

| ]]Price elasticity of supply]] | ]]Government revenue]] | ]]Decrease in consumption]] | ]]Incidence of tax paid by consumers]] | ]]Incidence of tax paid by product]] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| infinity | the least | the most | 100% | 0% |

| >1 | falling | sizeable | >50% | <50% |

| <1 | rising | minimal | <50% | >50% |

| 0 | the most | 0 | 0% | 100% |

- As the price elasticity of demand falls, and the price elasticity of supply rises, the greater the consumer’s share of a per-unit excise tax

- Conversely, as the price elasticity of demand rises and the price elasticity of supply falls, the producer’s share of a per-unit excise tax rises

Loss to society

There is also a cost to society when an excise tax is imposed on a competitive market

With the tax, consumers and producers demand and supply 20 fewer units than without the tax

For these 20 units that go unproduced, the marginal benefit to consumers exceeds the marginal costs to producers

20 units go unproduced and unconsumed resulting in an inefficient outcome

Economists call this area deadweight loss (DWL), or the net benefit sacrificed by society when such a per-unit tax is imposed (triangle labeled DWL)

Taxes create lost efficiency by moving away from the equilibrium market quantity where MB = MC to society.

The area of deadweight loss (triangle DWL) increases as the quantity moves further from the competitive market equilibrium quantity

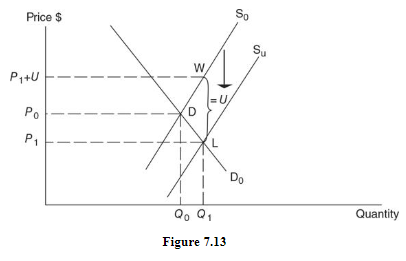

Subsidies

A per-unit subsidy on good X has the opposite effect of an excise tax

Firms respond as if the subsidy has lowered the marginal cost of production

Results in a downward vertical shift in the supply curve for good X

Assume the graph of the market for public university education

The subsidy decreases tuition to P1 and increases the number of undergraduate degrees received

Subsidy distorts the market and creates deadweight loss

Deadweight loss is the area of the triangle labeled DWL.

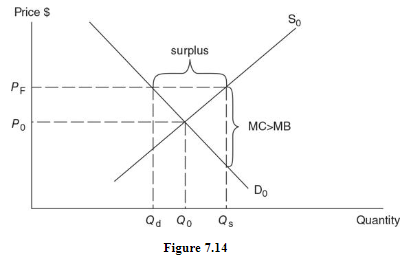

Price Floors

A price floor is a legal minimum price below which the product cannot be sold

An ineffective price floor would be a price set below the equilibrium price

Assume this to be a market for milk

The resulting surplus of milk is not eliminated through the market

The government usually agrees, as part of the price floor arrangement, to purchase the surplus milk

By providing an incentive for producers to produce beyond where MB = MC, the price floor policy causes efficiency to be lost.

For gallons of milk above Q0, MC > MB; there is an over allocation of resources to milk production

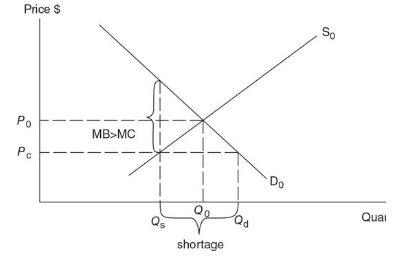

Price Ceilings

A price ceiling is a legal maximum price above which the product cannot be bought and sold

An effective price ceiling must be set below the equilibrium price

Assume this to be a market for rent-controlled households

This form of price control results in lost efficiency for society

When suppliers reduce their quantity supplied below the competitive equilibrium quantity, there is a situation where MB > MC, and we see under allocation of resources in the rental apartment market

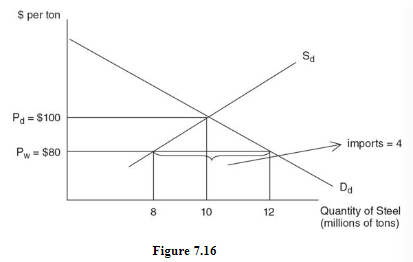

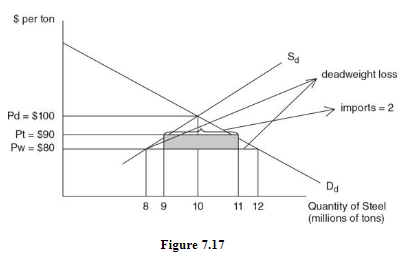

Trade Barriers

1. Tariffs

Revenue tariff is an excise tax levied on goods that are not produced in the domestic market.

Protective tariff is an excise tax levied on a good that is produced in the domestic market

Economic effects of the tariff

Consumers pay higher prices and consume less

Consumer surplus has been lost

Domestic producers increase output

Declining imports

Tariff revenue

Inefficiency

Deadweight loss

2. Quotas

- Import quota is a maximum amount of a good that can be imported into the domestic market

- Both hurt consumers with artificially high prices and lower consumer surplus.

- Both protect inefficient domestic producers at the expense of efficient foreign firms, creating a deadweight loss.

- Both reallocate economic resources toward inefficient producers.

- Tariffs collect revenue for the government, while quotas do not

Consumer Choice

Utility

- People demand things because those things make those people happy

- In economics, we call this happiness utility

- Consumption of more and more of something is likely to increase our total utility

- It is probably safe to say that the first pint in a week provides more marginal utility than the second, third, or fourth pint

- Total utility (TU) is the total amount of happiness received from the consumption of a certain amount of good.

- Marginal utility (MU) is the additional utility received from the consumption of the next unit of a good

- MU = ∆TU/∆Q

Unconstrained consumer choice

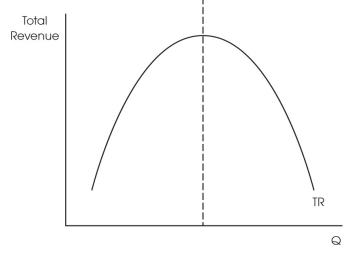

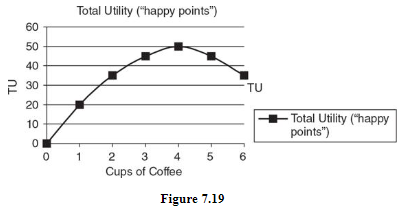

Total utility initially rises, peaks, and then begins to fall as more coffee is consumed(see fig above)

Even if the monetary price of good X is zero, the rational consumer stops consuming good X at the point where total utility is maximized.

Diminishing marginal utility

- The law of diminishing marginal utility says that in a given time period, the marginal utility from consumption of one more of that item falls

Constrained utility maximization

- With a fixed daily income and a price that must be paid, this individual is now a constrained utility maximizer

- When required to pay a price, the utility-maximizing consumer stops consuming when MB = P.

- This MB also represents the highest price, or “willingness to pay,” our consumer would be willing to pay for the next cup.

Demand curve revisited

- Law of diminishing marginal utility is the backbone of the law of demand

- Because of diminishing marginal utility, you offer to pay less for additional units

Utility maximizing rule

- Consumers maximize utility when they buy amounts of goods X and Y so that the marginal utility per dollar spent is equal for both goods

- MUx/Px = MUy/Py

- If the consumer has used all income and the above ratios are equal, they are said to be in equilibrium

- It is very important to remember that consuming more of one good causes the marginal utility to fall, but the total utility to rise

- To find the total utility of consuming cups of coffee, sum up the marginal utility of each cup consumed. Do the same for scones to calculate total utility

| ]]Cups of coffee]] | ]]MU of coffee]] | ]]# of Scones]] | ]]MU of Scone]] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 1 | 30 |

| 2 | 8 | 2 | 24 |

| 3 | 6 | 3 | 20 |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 |

| 5 | 2 | 5 | 14 |

| 6 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

- MUc/MUs = $2/$4= .5 or

- MUc/MUs = $1/$4 = .25