Chapter 1: Prehistoric Art

Key Notes

- Time Period

- Paleolithic Art : 30,000–8000 B.C.E.

- Neolithic Art : 8000–3000 B.C.E.

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Prehistoric art existed before writing.

- Prehistoric art has been affected by climate change.

- Prehistoric art can be seen in practical and ritual objects.

- Prehistoric art shows an awareness of everything from cosmic phenomena to the commonplace.

- Art-making

- The oldest objects are African or Asian.

- The first art forms appear as rock paintings, geometric patterns, human and animal motifs, and architectural monuments.

- Ceramics are first produced in Asia.

- The people of the Pacific are migrants from Asia, who bring ceramic-making techniques with them.

- European cave paintings and megalithic monuments indicate a strong tradition of rituals.

- Early American objects use natural materials, like bone or clay, to create ritual objects.

- Similarities with Asian shamanic religious practices can be found in ritual ancient American objects.

- Art history

- Scientific dating of objects has shed light on the use of prehistoric objects.

- Archaeology increases our understanding of prehistoric art.

- Archaeology: the scientific study of ancient people and cultures principally revealed through excavation

- Basic art historical methods can be used to understand prehistoric art, but our knowledge increases with findings made in other fields.

Prehistoric Background

- Two Eras in Pre-History

- Paleolithic Era: the Old Stone Age

- People were hunter-gatherers

- Neolithic Era: the New Stone Age

- People cultivated the earth and raised livestock.

- They lived in organized settlements, divided labor into occupations, and constructed the first homes.

- People created before they could write, cipher math, cultivate crops, domesticate animals, invent the wheel, or use metal.

- They painted before they had anything resembling clothes or lived in anything resembling a house.

- The need to create is among the strongest of human impulses.

Prehistoric Sculpture

➼ Camelid Sacrum in the Shape of a Canine

Details

- 14,000–7000 B.C.E.

- From Tequixquiac, Central Mexico

- Located at the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico

- Preserved in 1870 in the Valley of Mexico.

Materials

- Bone sculpture from a camel-like animal.

- The bone has been worked to create the image of a dog or wolf.

Content

- Carved to represent a mammal’s skull.

- One natural form is used to take the shape of another.

- The sacrum is the triangular bone at the base of a spine.

Context

- Second skull: A Mesoamerican idea

- The sacrum bone symbolizes the soul in some cultures, and for that reason it may have been chosen for this work.

Image

➼ Anthropomorphic Stele

Details

- 4th-millennium B.C.E.

- From Arabian Peninsula

- Mainly made of sandstone

- Preserved in National Museum, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Stele: an upright stone slab used to mark a grave or a site

Form and Content

- Anthropomorphic: having characteristics of the human form, although the form itself is not human.

- Belted robe from which hangs a double-bladed knife or sword.

- Double cords stretch diagonally across body with an awl unifying them.

Function: Religious or burial purpose, perhaps as a grave marker.

Context

- One of the earliest known works of art from Arabia.

- Found in an area that had extensive ancient trade routes.

Image

➼ Jade Cong

Details

- c. 3300–2200 B.C.E.

- From Liangzhu, China

- Made from a carved jade

- Preserved in Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, China

- Cong: a tubular object with a circular hole cut into a square-like cross-section

Form

- The circular hole is placed within a square.

- Abstract designs; the main decoration is a face pattern, perhaps of spirits or deities.

- Some have a haunting mask design in each of the four corners—with a bar-shaped mouth, raised oval eyes, sunken round pupils, and two bands that might indicate a headdress—which resembles the motif seen on Liangzhu jewelry.

Materials and Techniques

- Jade is a very hard stone, sometimes carved using drills or saws.

- The designs on congs may have been produced by rubbing sand.

- The jades may have been heated to soften the stone, or ritually burned as part of the burial process.

Context

- Jades appear in burials of people of high rank.

- Jades are placed in burials around bodies; some are broken, and some show signs of intentional burning.

- Jade religious objects are of various sizes and found in tombs, interred with the dead in elaborate rituals.

- The Chinese linked jade with the virtues of durability, subtlety, and beauty.

- Made in the Neolithic era in China.

Image

➼ The Ambum Stone

Details

- c. 1500 B.C.E.

- From Ambum Valley, Enga Province, Papua New Guinea

- Made from graywacke

- Preserved in National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Form

- Composite human/animal figure; perhaps an anteater head and a human body.

- Ridgeline runs from nostrils, over the head, between the eyes, and between the shoulders.

Theories

- Masked human.

- Anteater embryo in a fetal position; anteaters thought of as significant because of their fat deposits.

- May have been a pestle or related to tool making.

- Perhaps had a ritual purpose; considered sacred; maybe a fertility symbol.

- Maybe an embodiment of a spirit from the past, an ancestral spirit, or the Rainbow Serpent.

History

- Stone Age work; artists used stone to carve stone.

- Found in the Ambum Valley in Papua New Guinea.

- When it was “found,” it was being used as a ritual object by the Enga people.

- Sold to the Australian National Gallery.

- Damaged in 2000 when it was on loan in France; it was dropped and smashed into three pieces and many shards; it has since been restored.

Image

➼ Tlatilco Female Figurine

Details

- c. 1200–900 B.C.E.

- From Central Mexico, site of Tlatilco

- Made out of ceramic

- Preserved in Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey

Form

- Flipper-like arms, huge thighs, pronounced hips, narrow waists.

- Unclothed except for jewelry; arms extending from body.

- Diminished role of hands and feet.

- Female figures show elaborate details of hairstyles, clothing, and body ornaments.

Technique: Made by hand; artists did not use molds.

Function: May have had a shamanistic function

Context and Interpretation

- Some show deformities, including a female figure with two noses, two mouths, and three eyes, perhaps signifying a cluster of conjoined or Siamese twins and/or stillborn children.

- Bifacial images and congenital defects may express duality.

- Found in graves, and may have had a funerary context.

Image

➼ Terra cotta fragment

Details

- 1000 B.C.E.

- From Lapita, Reef Islands, Solomon Islands

- Made from incised terra cotta

- Preserved in University of Auckland, New Zealand

Form

- Pacific art is characterized by the use of curved stamped patterns: dots, circles, hatching; may have been inspired by patterns on tattoos.

- One of the oldest human faces in Oceanic art.

Materials

- Lapita culture of the Solomon Islands is known for pottery.

- Outlined forms: they used a comb-like tool to stamp designs onto the clay, known as dentate stamping.

Technique

- Did not use potter’s wheel.

- After pot was incised, a white coral lime was often applied to the surface to make the patterns more pronounced.

Tradition

- Continuous tradition: some designs found on the pottery are used in modern Polynesian tattoos and tapas.

Image

Prehistoric Paintings

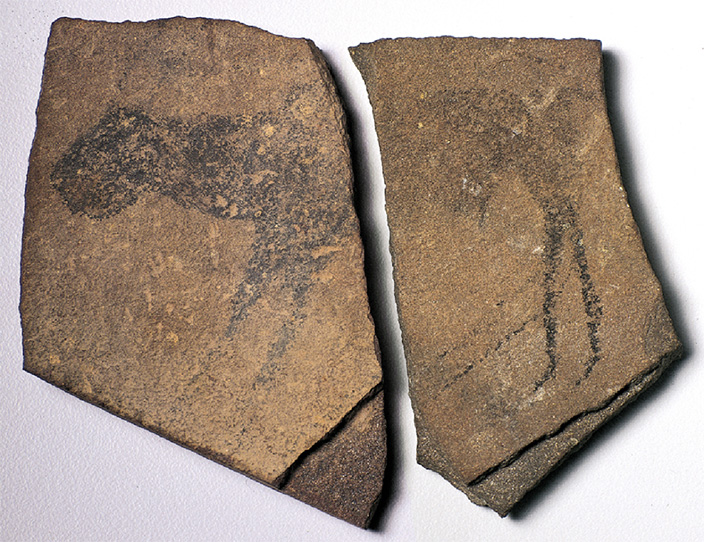

➼ Apollo 11 Stones

Details

- c. 25,500–25,300 B.C.E.

- Painted using charcoal on stone,

- Preserved in State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia

Form

- Animal seen in profile, typical of prehistoric painting.

- Perhaps a composite animal rather than a particular specimen.

Materials

- Done with charcoal.

Context

- Some of the world’s oldest works of art, found in Wonderwerk Cave in Namibia.

- Several stone fragments found.

- Originally brought to the site from elsewhere.

- Cave is the site of 100,000 years of human activity.

History

- Named after the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969, the year the cave was discovered.

Image

➼ Great Hall of the Bulls

Details

- 15,000–13,000 B.C.E.

- From Paleolithic Europe

- A rock painting,

- Found in Lascaux, France

Content

- 650 paintings: most common animals are cows, bulls, horses, and deer.

Form

- Bodies seen in profile; frontal or diagonal view of horns, eyes, and hooves; some animals appear pregnant.

- Twisted perspective: many horns appear more frontal than the bodies.

- Many overlapping figures.

Materials

- Natural products were used to make paint: charcoal, iron ore, plants.

- Walls were scraped to an even surface; paint colors were bound with animal fat; lamps lighted the interior of the caves.

- No brushes have been found.

- May have used mats of moss or hair as brushes.

- Color could have been blown onto the surface by mouth or through a tube, like a hollow bone.

Context

- Animals placed deep inside cave—some hundreds of feet from the entrance.

- Evidence still visible of scaffolding erected to get to higher areas of the caves.

- Negative handprints: are they signatures?

- Caves were not dwellings, as prehistoric people led migratory lives following herds of animals; some evidence exists that people did seek shelter at the mouths of caves.

Theories

- A traditional view is that they were painted to ensure a successful hunt.

- Ancestral animal worship.

- Represents narrative elements in stories or legends.

- Shamanism: a religion based on the idea that the forces of nature can be contacted by intermediaries, called shamans, who go into a trance-like state to reach another state of consciousness.

History

- Discovered in 1940; opened to the public after World War II.

- Closed to the public in 1963 because of damage from human contact.

- Replica of the caves opened adjacent to the original.

Image

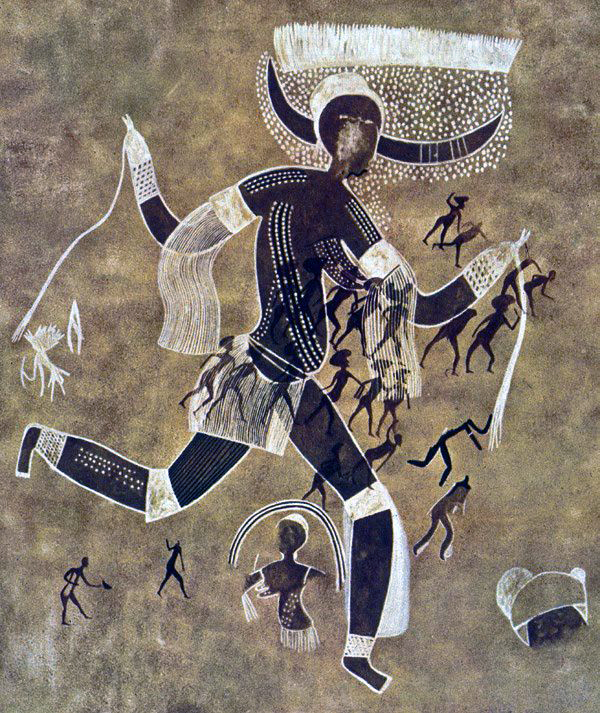

➼ Running Horned Woman

Details

- 6000–4000 B.C.E.

- A pigment on rock,

- Found in Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria

Form

- Composite view of the body.

- Many drawings exist—some are naturalistic, some are abstract, some have Negroid features, and some have Caucasian features.

- The female horned figure suggests attendance at a ritual ceremony.

Content

- Depicts livestock, wildlife, and humans

- Dots may reflect body paint applied for ritual or scarification; white patterns in symmetrical lines may reflect raffia garments.

Context

- More than 15,000 drawings and engravings were found at this site.

- At one time the area was grasslands; climate changes have turned it into a desert.

- The entire site was probably painted by many different groups over large expanses of time.

Image

➼ Beaker with Ibex Motifs

Details

- 4200–3500 B.C.E.

- From Susa, Iran

- Painted terra cotta

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form and Content

- Frieze of stylized aquatic birds on top, suggesting a flock of birds wading in a Mesopotamian river valley.

- Below are stylized running dogs with long narrow bodies, perhaps hunting dogs.

- The main scene shows an ibex with oversized abstract and stylized horns.

- Stylized: a schematic, nonrealistic manner of representing the visible world and its contents, abstracted from the way that they appear in nature

Materials and Techniques

- Probably made on a potter’s wheel, a technological advance; some suggest instead that it was handmade.

- Thin pottery walls.

Context and Interpretation

- In the middle of the horns is a clan symbol of family ownership; perhaps the image identifies the deceased as belonging to a particular group or family.

- Found near a burial site, but not with human remains.

- Found with hundreds of baskets, bowls, and metallic items.

- Made in Susa, in southwestern Iran.

Image

Prehistoric Architecture

- Menhirs: Large individual stones, erected singularly or in long rows stretching into the distance.

- Megaliths: a stone of great size used in the construction of a prehistoric structure

- Henge: a Neolithic monument, characterized by a circular ground plan. Used for rituals and marking astronomical events

- Lintel: a horizontal beam over an opening

- Post and Lintel Architecture: The most fundamental type of architecture in history.

➼ Stonehenge

Details

- c. 2500–1600 B.C.E.

- Made out of sandstone, Neolithic Europe,

- Found in Wiltshire, United Kingdom

Technique

- Post-and-lintel building; lintels grooved in place by the mortise and tenon system of construction.

- Mortise and tenon: a groove cut into stone or wood, called a mortise, that is shaped to receive a tenon, or projection, of the same dimensions

- Large megaliths in the center are over 20 feet tall and form a horseshoe surrounding a central flat stone.

- A central horseshoe is surrounded by lintel-connected megaliths.

- Hundreds of unidentified stones surrounded the monument.

- Builders lacked wheels and pulleys. Stones may have been transported on logs or a greased sleigh.

Context

- Each stone weighs over 50 tons, reflecting the structure's intended permanence.

- Some stones were imported from over 150 miles away, suggesting they were sacred.

History

- Perhaps took 1,000 years to build; gradually redeveloped by succeeding generations.

Probably built in three phases:

- First Phase: circular ditch 36 feet deep and 360 feet in diameter containing 56 pits called Aubrey Holes, named after John Aubrey who found them in the 18th century.

- Today the holes are filled with chalk.

- Second Phase: wooden structure, perhaps roofed.

- The Aubrey Holes may have been used as cremation burials at this time.

- Adult males were buried at these sites, generally, men who did not show a lifetime of hard labor, signifying it was a site for a select group of people.

- Third Phase: stone construction.

Tradition

- British Isles forests may have inspired wood circles.

- Stone circles are still common in Britain, indicating Neolithic popularity.

Theories

- As an observatory, it may predict eclipses and be oriented towards the summer and winter solstices.

- According to a new theory, elite males were buried at Stonehenge.

- An alternative theory suggests it was a healing site.

Image