Unit 2: Ancient Mediterranean, 3500 BCE–300 CE

Contextualization of Ancient Mediterranean Art

The Near East (3500 BCE–300 CE)

- The Near East is a region that includes modern-day Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, and parts of Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

- The art of the Near East dates back to the Neolithic period, around 8000 BCE.

- The Sumerians, who lived in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) around 4000 BCE, created some of the earliest known works of art in the region, including cylinder seals and votive statues.

- The Babylonians, who followed the Sumerians, created intricate relief sculptures and decorative tiles.

- The Persians, who ruled the region from the 6th to the 4th century BCE, created elaborate palaces and tombs, such as the famous Persepolis.

- Islamic art, which emerged in the 7th century CE, is characterized by intricate geometric patterns, calligraphy, and the use of bright colors.

- The art of the Near East has been influenced by various religions, including Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

- Many of the works of art from the Near East are now housed in museums around the world, including the British Museum in London and the Louvre in Paris.

Egypt (3000–30 BCE)

- Egyptian art is one of the oldest and most enduring art forms in the world. It is characterized by its highly stylized and symbolic representations of people, animals, and gods.

- Early Dynastic Period (3000–2686 BCE)

- Art during this period was highly stylized and focused on the representation of the human form.

- Sculptures were typically made from limestone and depicted kings and queens in a rigid, formal pose.

- Paintings were often found in tombs and depicted scenes from daily life, such as hunting and fishing.

- Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BCE)

- The Old Kingdom is known for its monumental architecture, such as the pyramids of Giza.

- Sculptures during this period were highly realistic and depicted the pharaohs as powerful and divine beings.

- Paintings were often used to decorate tombs and depicted scenes from the afterlife.

- Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BCE)

- Art during the Middle Kingdom was characterized by a more naturalistic style.

- Sculptures were often made from bronze and depicted everyday people, such as farmers and craftsmen.

- Paintings during this period were highly detailed and often depicted scenes from daily life.

- New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE)

- The New Kingdom is known for its elaborate tombs and temples, such as the temple of Karnak.

- Sculptures during this period were highly detailed and often depicted gods and goddesses.

- Paintings were highly symbolic and often depicted scenes from mythology and religion.

- Late Period (664–332 BCE)

- Art during the Late Period was heavily influenced by Greek and Roman art.

- Sculptures were often made from bronze and depicted gods and goddesses in a more naturalistic style.

- Paintings during this period were highly detailed and often depicted scenes from daily life.

Greece (900–30 BCE)

- Ancient Greece was subdivided into city-states, comparable to Near Eastern civilizations. It is renowned for its democracy, military might, and art in particular.

- Geometric Period (900-700 BCE)

- Characterized by geometric shapes and patterns

- Pottery was the main art form

- Used for storage and funerary purposes

- Figures were stylized and abstract

- Archaic Period (700-480 BCE)

- Transition from geometric to realistic art

- Sculptures were made of marble and bronze

- Kouros and Kore statues were popular

- Depicted idealized human forms

- Pottery became more decorative

- Classical Period (480-323 BCE)

- Considered the height of Greek art

- Emphasis on balance, harmony, and proportion

- Sculptures depicted realistic human forms

- Contrapposto pose was introduced

- Parthenon was built during this period

- Hellenistic Period (323-30 BCE)

- Art became more emotional and dramatic

- Sculptures depicted movement and expression

- Portraiture became popular

- Laocoon and His Sons is a famous sculpture from this period

Etruria (900-270 BCE)

- Etruria was a civilization in ancient Italy that flourished from the 9th to the 3rd century BCE.

- Etruscan art was heavily influenced by Greek art, but it also had its own unique style.

- It was characterized by its use of terracotta, bronze, and gold.

- It was also known for its intricate and detailed designs, which often depicted scenes from mythology and daily life.

- Etruscan tombs were often decorated with frescoes, which depicted scenes from the afterlife and the deceased's life.

- Etruscan sculpture was also highly detailed and often depicted human figures in a naturalistic style.

- Etruscan pottery was also highly prized and was often decorated with intricate designs and scenes from mythology.

- Etruscan art declined after the Roman conquest of Etruria in the 3rd century BCE, but its influence can still be seen in Roman art and architecture.

Rome (750 BCE -350 CE)

- Rome was founded in 753 BCE and became a powerful city-state in the Mediterranean world.

- Roman art was heavily influenced by Greek art, but it also had its own unique characteristics.

- Early Rome (750-500 BCE)

- Art during this period was mostly utilitarian and focused on practical objects such as pottery and weapons.

- The Etruscan civilization, which was located north of Rome, also had a significant influence on early Roman art.

- Republican Rome (500-27 BCE)

- During this period, Rome became a republic and art became more focused on public works and propaganda.

- Roman art during this period was characterized by realism and a focus on the human form.

- Sculpture was the most prominent form of art, with many examples of busts and statues of important figures.

- Imperial Rome (27 BCE- 350 CE)

- The Roman Empire was established in 27 BCE and art became more grandiose and focused on glorifying the emperor and the empire.

- Architecture became a prominent form of art, with examples such as the Colosseum and the Pantheon.

- Mosaics and frescoes also became popular, with many examples found in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Ancient Mediterranean Artworks

➼ White Temple and its Ziggurat

Details

- c. 3500–3000 B.C.E

- Made up of mud brick

- Found in Uruk (modern Warka), Iraq

Form

- Buttresses spaced across the surface to create a contrasting light-and-shadow pattern.

- The ziggurat tapers downward so that rainwater washes off.

- Entire form resembles a mountain, creating a contrast between the vast flat terrain and the man-made mountain.

- Bent-axis plan: ascending the stairs requires angular changes of direction to reach the temple

Function

- On top of the ziggurat is a terrace for outdoor rituals and a temple for indoor rituals.

- The temple on the top was small, set back, and removed from the populace; access was reserved for royalty and clergy; only the base of the temple remains.

- The temple interior contained a cella and smaller rooms meant for the deities to assemble before a select group of priests.

- Cella: the main room of a temple where the god is housed

Materials

- Mud-brick building built on a colossal scale and covered with glazed tiles or cones.

- Whitewash: was used to disguise the mud appearance; hence the modern name of White Temple.

Context

- Large settlement at Uruk of 40,000, based on agriculture and specialized labor.

- Uruk: May be the first true city in history; the first with monumental architecture.

- Ziggurat sited within the city.

- Anu: The god of the sky, the most important Sumerian deity.

- Gods descend from the heavens to a high place on Earth; hence the Sumerians built ziggurats as high places.

- Four corners oriented to the compass; cosmic orientation.

➼ Statues of Votive Figures

Details

- From the Square Temple at Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar, Iraq)

- c. 2700 B.C.E.

- Gypsum inlaid with shell and black limestone

- Preserved in Iraq Museum ,Baghdad, and the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

- Votive: Offered in fulfillment of a vow or a pledge

Form

- Figures are of different heights, denoting hierarchy of scale.

- Hands are folded in a gesture of prayer.

- Huge eyes in awe, spellbound, perhaps staring at the deity.

- Men are bare-chested; wearing belt and skirt; beard flows in a ripple pattern.

- Women are dressed draped over one shoulder.

- Arms and feet cut away.

- Pinkie in a spiral; chin a wedge shape; ear a double volute.

Function

- Some have inscriptions on the back — “It offers prayers.”

- Other inscriptions tell the names of the donors or gods.

- Figures represent mortals; placed in a temple to pray before a sculpture of a god.

Context

- Gods and humans physically present in their statues.

- None have been found in situ, but buried in groups under the temple floor.

➼ Standard of Ur

Details

- From the Royal Tombs at Ur (modern Tell el-Muqayyar, Iraq)

- c. 2600–2400 B.C.E.

- A wood inlaid with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone

- Preserved in British Museum, London

Form

- Figures have broad frontal shoulders; bodies in profile; twisted perspective.

- Emphasis on eyes, eyebrows, ears.

- Organized in registers; figures stand on ground lines.

- Read from bottom to top.

- Ground line: a baseline upon which figures stand

- Ground plan: the map of a floor of a building

- Register: a horizontal band, often on top of another, that tells a narrative story

Content

- Two sides: war side and peace side; may have been two halves of a narrative; early example of a historical narrative.

- War side: Sumerian king, half a head taller than the others, has descended from his chariot to inspect captives brought before him, some of whom are debased by their nakedness; in the lowest register, chariots advance over the dead.

- Peace side: food brought in a procession to the banquet; musician plays the lyre; the ruler is the largest figure—he wears a kilt made of tufts of wool; may have been a victory celebration after a battle.

Context

- Found in a tomb at the royal cemetery at Ur in modern Iraq.

- Reflects extensive trading network: lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, shells from the Persian Gulf, and red limestone from India.

- Lapis lazuli: a deep-blue stone prized for its color

Theories

- It may have been part of a musical instrument's soundbox; the term "standard" comes from the idea that it was carried on a pole.

- The two scenes may show an ideal Sumerian ruler as a victorious general and a father who promotes general welfare.

➼ Code of Hammurabi

Details

- From Babylon (modern Iran), Susian

- c. 1792–1750 B.C.E.

- Made up of basalt

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form: A stele meant to be placed in an important location.

Function

- One of the earliest law codes is below the main scene, symbolizing a ruler's need to establish civic harmony in a civilized world.

- 300 law entries below the images symbolize Shamash giving Hammurabi the laws.

Content

- Shamash: Sun god, enthroned on a ziggurat, hands Hammurabi a rope, a ring, and a rod of kingship.

- Shamash is in a frontal view and a profile at the same time; their headdress is in profile; rays (wings?) appear from behind his shoulders.

- Shamash’s beard is fuller than Hammurabi’s, illustrating Shamash’s greater wisdom.

- Shamash, judge of the sky and the earth, with a tiara of four rows of horns, presents signs of royal power, the scepter and the ring, to Hammurabi.

- They stare at one another directly even though their shoulders are frontal; composite views.

- Hammurabi is depicted with a speaking/greeting gesture.

Context

- Written in cuneiform.

- Text in Akkadian language, read right to left and top to bottom in 51 columns.

- Law articles are written in a formula: “If a person has done this, then that will happen to him.”

History

- Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.E.) united Mesopotamia in his lifetime.

- Took Babylon from a small power to a dominant kingdom; after his death, the empire dwindled.

➼ Lamassu

Details

- From the citadel of Sargon II, Dur Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad, Iraq)

- c. 720–705 B.C.E.,

- An alabaster

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form

- Human-headed animal guardian figures: face of a person, ears and body of a bull.

- Winged.

- Appears to have five legs: when seen from the front, it seems to be standing at attention; when seen from the side, the animal seems to be walking.

- Faces exude calm, serenity, and harmony.

Materials

- Carved from a single piece of stone.

- Meant to hold up the walls and arch of a gate.

- Stone is rare in Mesopotamian art and contrasts greatly with the mud-brick construction of the palace.

Function

- Meant to ward off enemies both visible and invisible.

- Inscriptions in cuneiform at the bottom portion of the lamassu declare the power of the king and curse his enemies.

Context

- Sargon II founded the capital at Khorsabad; the city was surrounded by a wall with seven gates.

- The protective spirits (guardians) were placed at either side of each gate.

➼ Apadana of Darius and Xerxes

Details

- c. 520–465 B.C.E.

- Mainly made up of limestone

- Found in Persepolis, Iran

- Apadana: an audience hall in a Persian palace

Form

- Built on artificial terraces, as is most Mesopotamian architecture.

- Columns have a bell-shaped base that is an inverted lotus blossom; the capitals are bulls or lions.

- Everything seems to have been built to dwarf the viewer.

Function

- Built for lavish receptions and festivals, not palaces.

- Lamassu gates welcome visitors.

- The Gates of All Nations proudly proclaim this complex as the seat of a great empire.

- Audience hall (apadana): It had 36 columns covered by a wooden roof; held thousands of people; was used for the king’s receptions; had stairways adorned with reliefs of the New Year’s festival and a procession of representatives of 23 subject nations.

- Hypostyle hall: An indication of one of the many cultures that inspired the complex.

Material: Mud brick with stone facing; stone symbolizing durability and strength.

Context and Interpretation

- Darius chose this central location in Persia to protect the treasury, and relief sculptures show delegations from across the empire bringing gifts for storage.

- The immortals, the king's guard, originally painted and adorned with metal accessories, were carved into the stairs.

- The stairs have a central relief of the king enthroned with attendants, the crown prince behind him, and dignitaries bowing.

- Static processions represent a peaceful world.

History

- Built by Darius I and Xerxes I; destroyed by Alexander the Great, perhaps as an act of revenge for the destruction of the Acropolis in Athens.

- Many cultural influences (Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians) contributed to the building of the site, as a sign of Persian cosmopolitan imperial culture.

➼ Palette of King Narmer

Details

- From Predynastic Egypt

- 3000–2920 B.C.E.

- A graywacke

- Found in Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Form

- Hierarchy of Scale

- Figures stand on a ground line.

- Narrative.

- Schematic lines delineate Narmer’s muscle structure: forearm veins and thigh muscles are represented by straight lines, the kneecaps by half circles.

- Composite view of the human body: mostly seen in profile, but chest, eye, and ear are frontal.

- Hieroglyphics explain and add to the meaning, and they identify Narmer in the cartouche.

Function

- Palette used to prepare eye makeup for the blinding sun, although this palette was probably commemorative.

- Palettes carved on two sides were for ceremonial purposes.

Content

- Relief sculpture depicting King Narmer uniting Upper and Lower Egypt.

- Depicted four times at the top register is Hathor, a god as a cow with a woman’s face, or Bat, a sky goddess who has the power to see the past and the future, or a bull which symbolizes the power and strength of the king.

- On the front:

- Narmer, the largest figure, wears the Lower Egyptian cobra crown and inspects the enemy's beheaded corpses from above.

- Narmer's sandal bearer follows four standard bearers and a priest.

- In the center, mythical animals with long necks are harnessed, possibly symbolizing unification. At the bottom, a bull destroys a city fortress. — Narmer knocking over his enemies.

- On the back:

- The falcon is Horus, god of Egypt, who triumphs over Narmer’s foes; Horus holds a rope around a man’s head and a papyrus plant, symbols of Lower Egypt.

- Narmer has a symbol of strength, the bull’s tail, at his waist; wears a bowling-pin-shaped crown as king of united Egypt, beating down an enemy.

- A servant behind Narmer holds his sandals as he stands barefoot on the sacred ground as a divine king.

- Defeated Egyptians lie beneath his feet.

Theories

- Represents the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one ruler.

- Unification is expressed as a concept or goal to be achieved.

- May represent a balance of order and chaos.

- May reference the journey of the sun god.

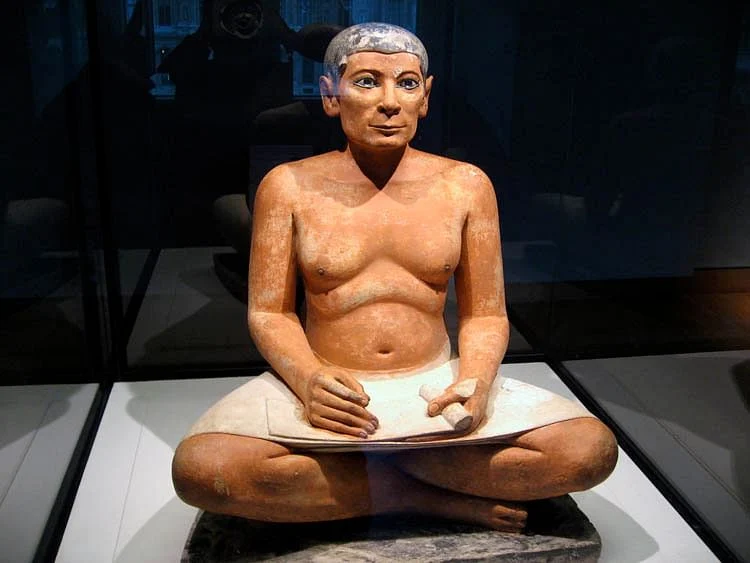

➼ Seated Scribe

Details

- From Saqqara, Egypt, Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty

- c. 2620–2500 B.C.E.

- A painted limestone

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form

- Not a pharaoh: sagging chest and realistic body rather than the idealistic features reserved for a pharaoh; the scribe contrasts with the ideally portrayed pharaoh.

- Figure has high cheekbones, hollow cheeks, and a distinctive jawline.

- Meant to be seen from the front.

- Color still remains on the sculpture.

Function: Created for a tomb at Saqqara as a provision for the ka.

Content

- Amazingly lifelike but not a portrait—rather, it’s a conventional image of a scribe.

- Inlaid crystal eyes.

- Holds papyrus in his lap; his writing instrument (now gone) was in his hand ready to write.

Context

- Attentive expression; thin angular face; in readiness for the words the pharaoh might dictate.

- Seated on the ground to indicate his comparative low state.

➼ Great Pyramids (Menkaura, Khafre, and Khufu)

Details

- c. 2550–2490 B.C.E.

- From Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty

- A cut limestone,

- Found in Giza, Egypt

Form

- Each pyramid is a huge pile of limestone with a minimal interior that housed the deceased pharaoh.

- Each pyramid had an enjoining mortuary temple used for worship.

Function

- Giant monuments to dead pharaohs: Menkaura, Khufu, and Khafre.

- Preservation of the body and tomb contents for eternity.

- Some scholars also suggest that the complex served as the king’s palace in the afterlife.

Context

- Each pyramid has a funerary complex adjacent connected by a formal pathway used for carrying the dead pharaoh’s body to the pyramid to be interred.

- Shape may have been influenced by a sacred stone relic called a benben, which is shaped like a sacred stone found at Heliopolis.

- Heliopolis was the center of the sun god cult.

- Each side of the pyramid is oriented toward a point on the compass, a fact pointing to an association with the stars and the sun.

- Giza temples face east, the rising sun, and have been associated with the god Re.

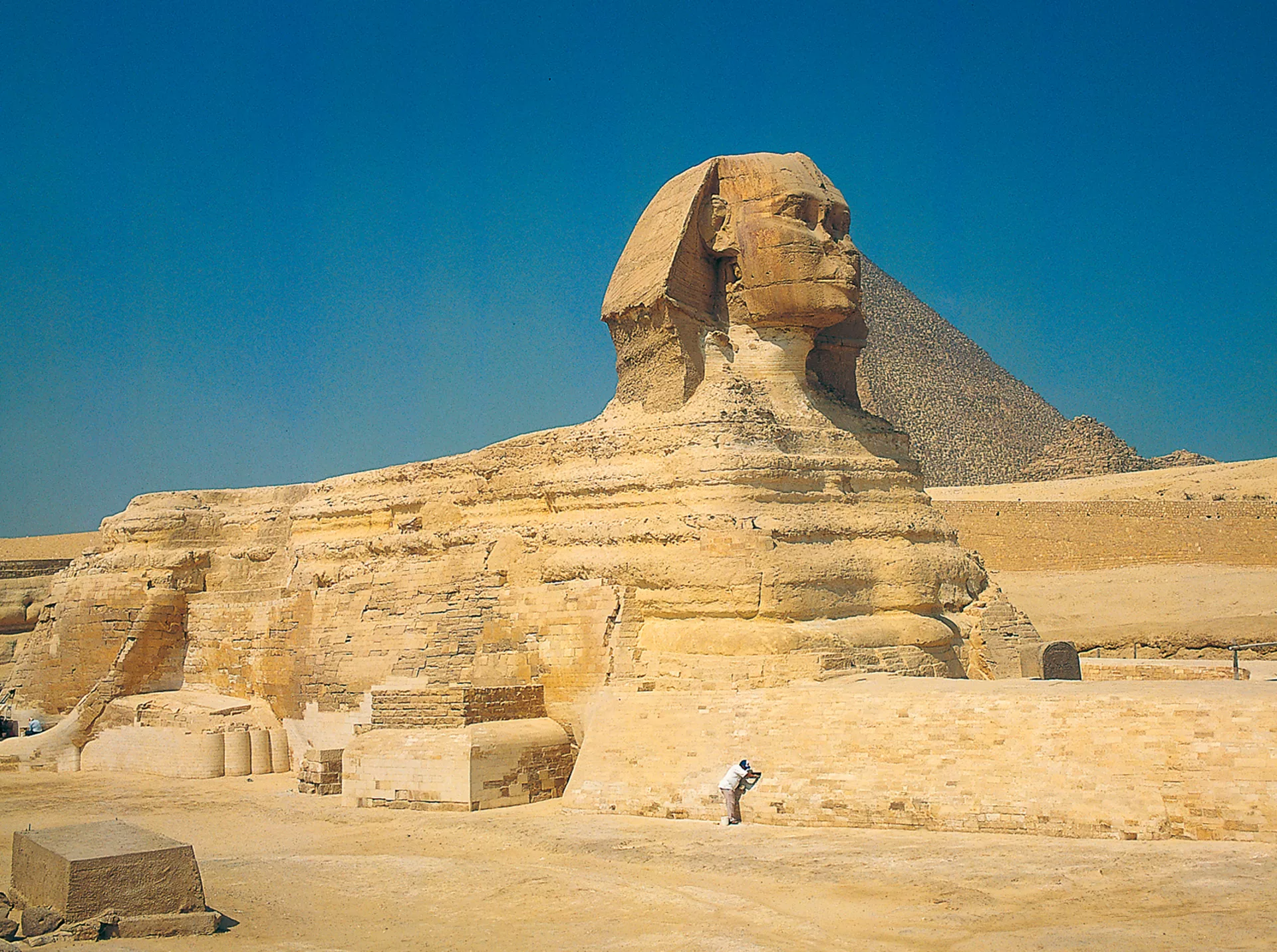

➼ Great Sphinx

Details

- C. 2500 B.C.E.

- A limestone

- Found in Giza, Egypt

Form

- Carved in situ from a huge rock; colossal scale.

- In situ: a Latin expression that means that something is in its original location

- Body of a lion, head of a pharaoh and/or god.

- Originally brightly painted to stand out in the desert behind the figure, which once rose near ramps rising from the Nile.

Function: The Sphinx seems to be protecting the pyramids behind it, although this theory has been debated.

Context and Interpretation

- Very generalized features, although some say it may be a portrait of Khafre.

- Cats are royal animals in ancient Egypt, probably because they saved the grain supply from mice.

History

- Head of the Sphinx badly mauled in the Middle Ages.

- Fragment of the Sphinx’s beard is in the British Museum.

➼ King Menkaura and Queen

Details

- From the Old Kingdom, 4th Dynasty

- 2490– 2472 B.C.E.

- A graywacke

- Found in Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Form

- Two figures attached to a block of stone; arms and legs not cut free.

- Traces of red paint exist on Menkaura’s face and black paint on the queen’s wig.

- Figures seem to stride forward, but simultaneously are anchored to the stone behind; it is unusual for the female figure to be striding with the male.

- Figures stare out into space (the afterlife?).

Function

- Receptacle for the ka of the pharaoh and his queen.

- Ka: the soul, or spiritual essence, of a human being that either ascends to heaven or can live in an Egyptian statue of itself

- Wife’s simple and affectionate gesture, and/or presenting him to the gods.

Materials: Extremely hard stone used; symbolizes the permanence of the pharaoh’s presence and his strength on earth.

Context

- Menkaura’s powerful physique and stride symbolize his kingship, as does his garb: nemes on the head, an artificial beard, and a kilt with a tab.

- Original location was the temple of Menkaura’s pyramid complex at Giza.

- Society’s view of women is expressed in the ankle-length tightly draped gown covering the queen’s body; men and women of the same height indicated equality.

- Society’s view of the king is expressed in his broad shoulders, muscular arms and legs, and firm stomach.

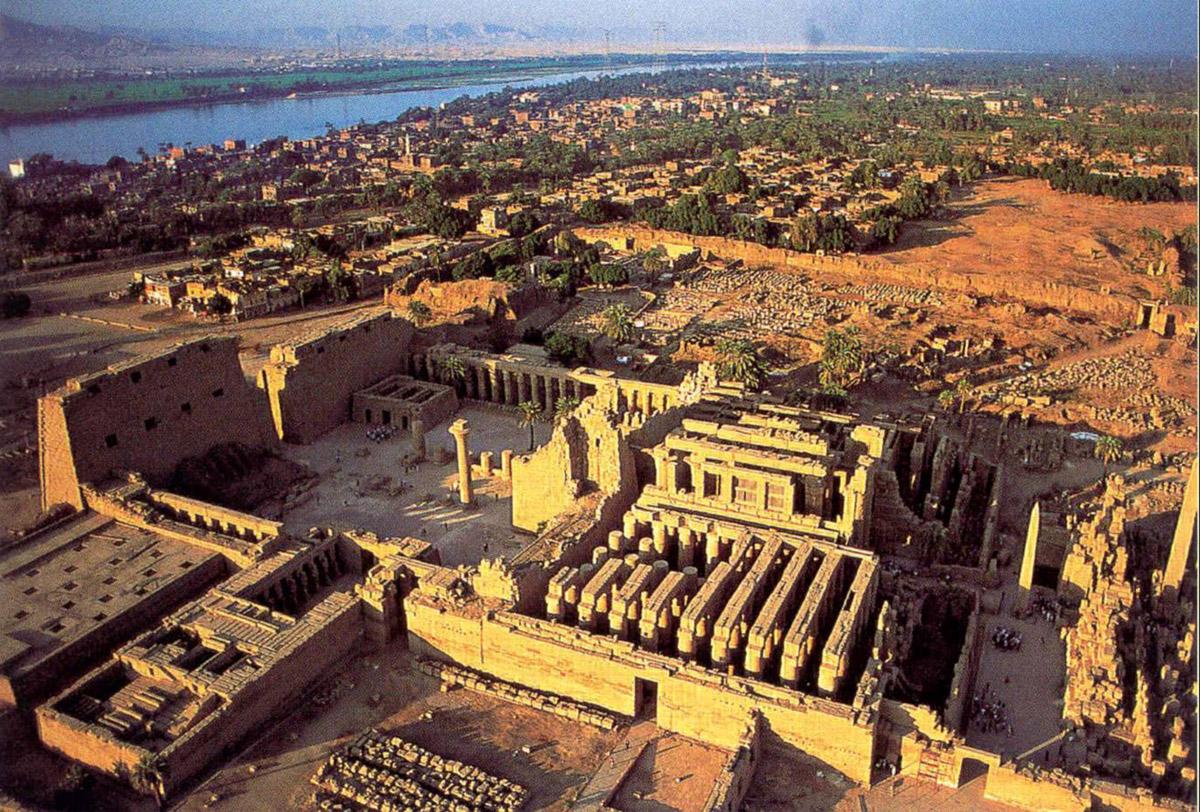

➼ Temple of Amun-Re and Hypostyle Hall

Details

- Temple: 1550 B.C.E.

- Hall: 1250 B.C.E.

- From New Kingdom, 18th and 19th Dynasties

- A cut sandstone and mud brick

- Found in Karnak, near Luxor, Egypt

- Hypostyle: a hall that has a roof supported by a dense thicket of columns

Form

- Axial plan: a building with an elongated ground plan

- Pylon temple.

- Pylon: a monumental gateway to an Egyptian temple marked by two flat, sloping walls between which is a smaller entrance

- Hypostyle halls.

- Massive lintels link the columns together.

- Huge columns, tightly packed together, admit little light into the sanctuary.

- Tallest columns have papyrus capitals; a clerestory allows some light and air into the darkest parts of the temple.

- Clerestory: a roof that rises above lower roofs and thus has window space beneath carved into a surface so that the figures seem to project forward

- Columns elaborately painted.

- Columns carved in sunken relief.

- Sunken relief: a carving in which the outlines of figures are deeply

- Bottom of columns have bud capitals.

- Massive walls enclose complex.

- Enter complex through massive sloped pylon gateway into a peristyle courtyard, then through a hypostyle hall, and then into the sanctuary, where few were allowed.

- Peristyle: a colonnade surrounding a building or enclosing a courtyard

Function

- Egyptian temple for the worship of Amun-Re.

- God housed in the darkest and most secret part of the complex, only accessed by priests and pharaohs.

Context

- Adjacent is an artificial sacred lake—a symbol of the sacred waters of the world that existed before time.

- Located on the east side of the Nile, linked by a road with the Karnak temple for the Opet festival.

- The complex was built near this lake over time; symbolically, it arose from the waters the way civilization did.

- Theory that the temple represents the beginnings of the world:

- Pylons are the horizon.

- Floor rises to the sanctuary of the god.

- Temple roof is the sky.

- Columns represent plants of the Nile: lotus, papyrus, palm, etc.

History

- Built by succeeding generations of pharaohs over a great expanse of time.

➼ Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Details

- c. 1473–1458 B.C.E.

- New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty,

- A sandstone partly carved into a rock cliff

- Found near Luxor, Egypt

Form

- Three colonnaded terraces and two ramps.

- Visually coordinated with the natural setting; long horizontals and verticals of the terraces and colonnades repeat the patterns of the cliffs behind; patterns of dark and light in the colonnade are reflected in the cliffs.

Function

- Hatshepsut declared that she built the temple as “a garden for my father, Amun”

- Only used for special religious events; lacks subsidiary buildings for offering storage, priest housing, temple administration, workshops, and other functions.

- Cultic purity prevented the royal burial in the temple.

- Valley of the Kings led to the royal tomb in the mountain behind the temple.

Context

- First time the achievements of a woman are celebrated in art history; Hatshepsut’s body is interred elsewhere.

- Temple aligned with the winter solstice, when light enters the farthest section of the interior.

- Located on the west side of the Nile across from Thebes.

- Perhaps designed by Senenmut, a high-ranking official in Hatshepsut’s court.

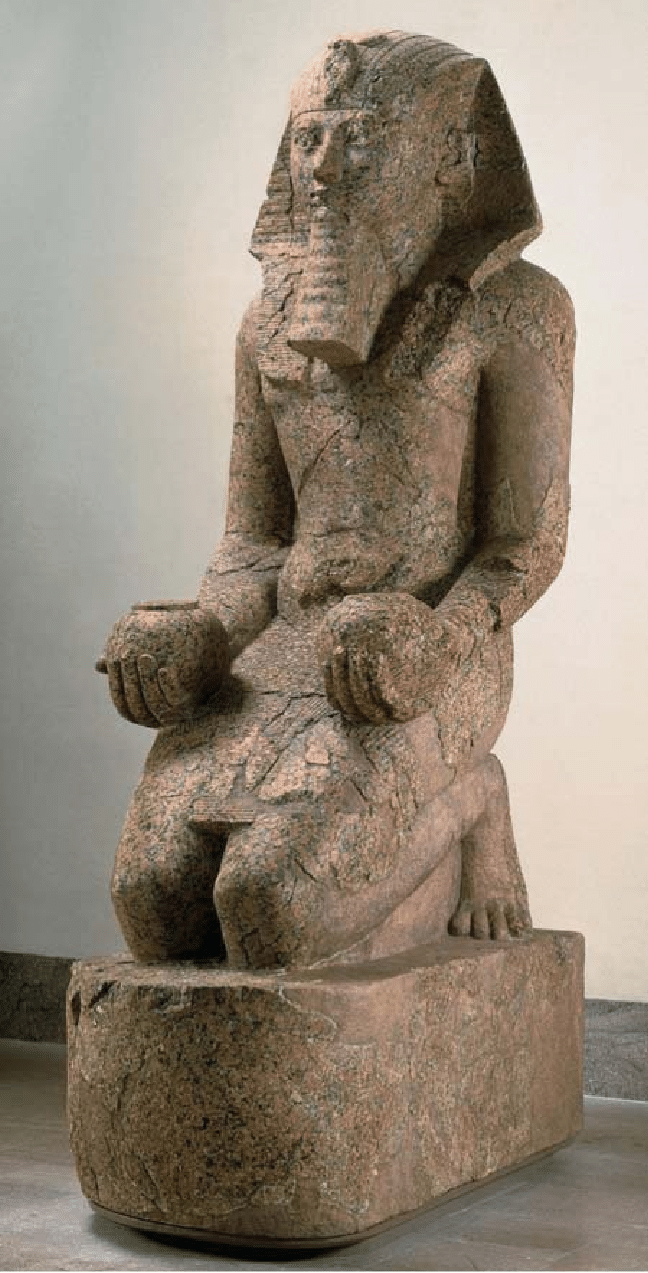

➼ Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut

Details

- 1473–1458 B.C.E.

- Made of red granite

- Found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

- Male pharaonic attributes: nemes or headcloth, false beard, kilt.

- Wears the white crown of Upper Egypt.

- Queen is depicted in male costume of a pharaoh, yet slender proportions and slight breasts indicate femininity.

Function

- Statue of the god brought before sculpture in a procession.

- Processions up the mortuary temple passed in front of this statue of Hatshepsut.

- One of 200 statues placed around the complex.

Context

- One of 10 statues of Hatshepsut with offering jars, part of a ritual in honor of the sun god; pharaoh would kneel only before a god.

- Inscription on base says she is offering plants to Amun, the sun god.

➼ Akhenaton, Nefertiti, and Three Daughters

Details

- 1353–1335 B.C.E.

- New Kingdom (Amarna) 18th Dynasty

- Made up of limestone

- Found in Egyptian Museum, Berlin

Content

- Akhenaton holds his eldest daughter (left), ready to be kissed.

- Nefertiti holds her daughter (right) with another daughter on her shoulder.

- Intimate family relationships are extremely rare in Egyptian art.

Form

- State religion shift indicated by an evolving style in Egyptian art:

- Smoother, curved surfaces

- Low-hanging bellies.

- Slack jaws.

- Thin arms.

- Epicene bodies.

- Heavy-lidded eyes.

- At the end of the sun’s rays, ankhs point to the king and queen.

- Ankh: an Egyptian symbol of life

Function: The domestic environment was new in Egyptian art; the panel is for an altar in a home

Technique

- Sunken relief, which is less likely to be damaged than raised relief.

- Sunken relief creates deeper shadows and can be appreciated in the sunlight.

Context

- Akhenaton abandoned Thebes and created a new capital, originally named Akhenaton and later changed to Amarna; the style of art from this period is called the Amarna Style.

- Amarna style: art created during the reign of Akhenaton, which features a more relaxed figure style than in Old and Middle Kingdom art

- The state religion was changed by Akhenaton to the worship of Aton, symbolized by the sun-disk with a cobra; he changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaton to reflect his devotion to the one god Aton.

- Akhenaton and Nefertiti are having a private relationship with their new god, Aton.

- After Akhenaton’s reign, the Amarna style was slowly replaced by more traditional Egyptian representations.

➼ Innermost Coffin of King Tutankhamun’s tomb

Details

- From New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty

- c. 1323 B.C.E.

- A gold with an inlay of enamel and semi-precious stones

- Found in Egyptian Museum, Cairo

Form

- Gold coffin (6 feet, 7 inches long) containing the body of the pharaoh.

- Smooth, idealized features on the mask of the boy king.

- Holds a crook and a flail, symbols of Osiris.

Function: Mummified body of King Tutankhamun was buried with 143 objects, on his head, neck, abdomen, and limbs; a gold mask was placed over his head.

Context

- When Akhenaton died, two pharaohs ruled briefly, and then his son Tutankhamun reigned for ten years, from age 9 to 19.

- Tutankhamun’s father and mother were brother and sister; his wife was his half-sister; perhaps he was physically handicapped because of genetic inbreeding.

History: Famous tomb was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922.

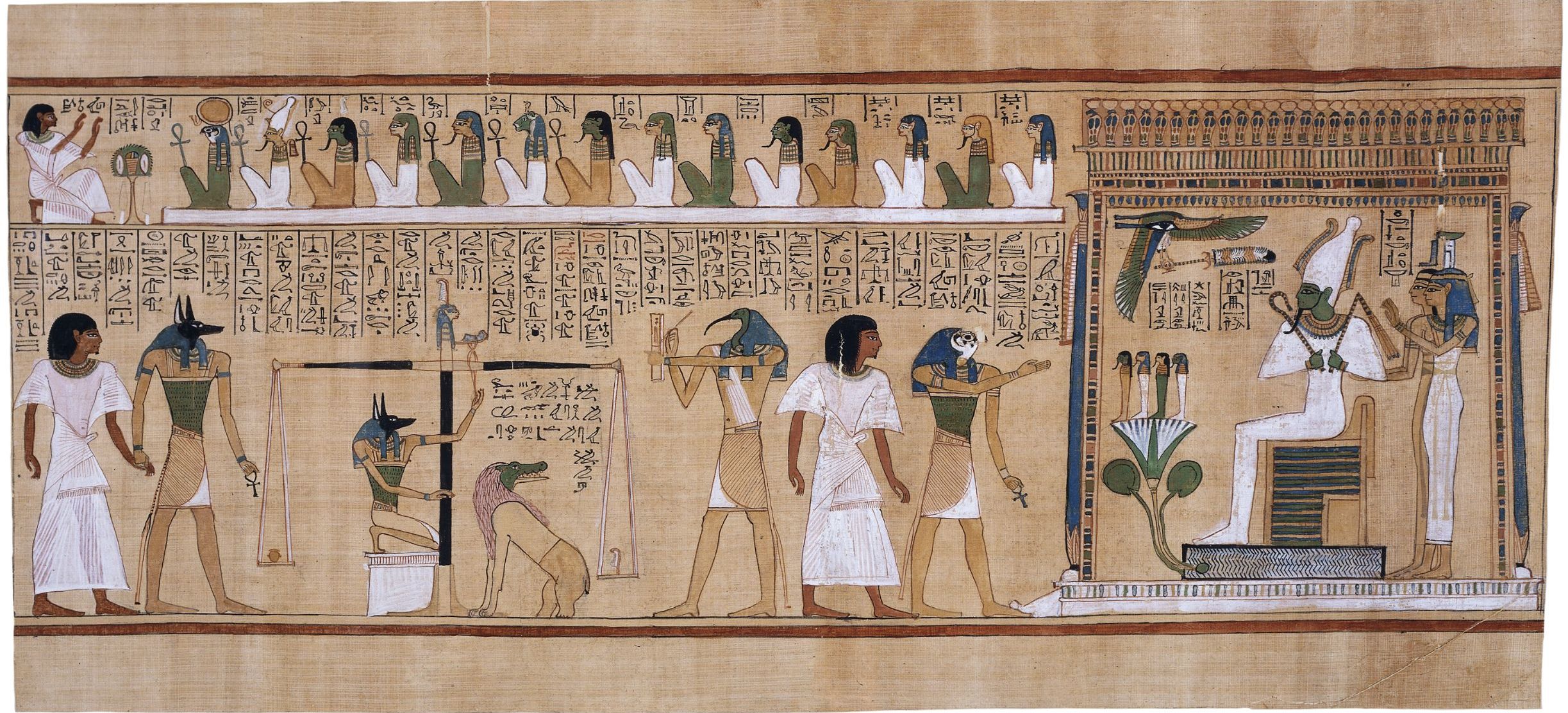

➼ Last Judgment of Hunefer

Details

- Page from the Book of the Dead

- From New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty

- c. 1275 B.C.E.

- A painted papyrus scroll

- Found in British Museum, London

Form: Narrative on a uniform register (read right to left).

Function: Illustration from the Book of the Dead, an Egyptian book of spells and charms that acted as a guide for the deceased to make his or her way to eternal life.

Content

- Top register — Hunefer in white at left before a row of judges.

- Main register — the jackal-headed god of embalming, Anubis, leads the deceased into a hall, where his soul is weighed against a feather. If his sins weigh more than a feather, he will be condemned.

- Ammit: The hippopotamus/lion figure; between the scales, will eat the heart of an evil soul.

- Thoth: A god who has the head of a bird; the stenographer writing down these events in the hieroglyphics that he invented.

- Osiris: god of the underworld, enthroned on the right; will subject the deceased to a day of judgment.

Context

- Hunefer: A scribe who had priestly functions.

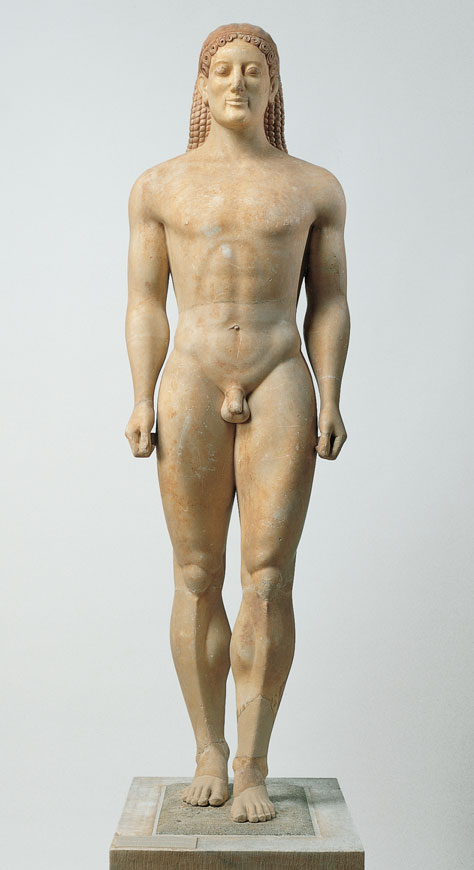

➼ Anavysos Kouros

Details

- From Archaic Greek

- c. 530 B.C.E.

- A marble with remnants of paint

- Found in National Archaeological Museum, Athens

- Kouros (female: kore): An archaic Greek sculpture of a standing youth

Form

- Emulates the stance of Egyptian sculpture but is nude; arms and legs are largely cut free from the stone.

- Rigidly frontal.

- Freestanding and able to move; in contrast, many Egyptian works are reliefs or are attached to the stone.

- Hair is knotted and falls in neatly braided rows down the back.

- Some paint survives, some of it encaustic, which would have given the sculpture greater life.

- Encaustic: a type of painting in which colors are added to hot wax to affix to a surface

- “Archaic smile” meant to enliven the sculpture.

Function

- Grave marker, replacing huge vases of the Geometric period.

- Sponsored by an aristocratic family.

Content

- Not a real portrait but a general representation of the dead.

- Named after a young military hero, Kroisos; the inscription at the base identifies him: “Stand and grieve at the tomb of Kroisos, the dead, in the front line slain by the wild Ares.”

➼ Peplos Kore

Details

- From the Acropolis, Archaic Greek

- c. 530 B.C.E.

- A marble and painted details

- Found in Acropolis Museum, Athens

- Peplos: a garment worn by women in ancient Greece, usually full length and tied at the waist

Form

- Hand emerges into the viewer’s space, breaks out of the mold of static Archaic statues.

- Indented waist.

- Breasts revealed beneath drapery.

- Rounded and naturalistic face.

- Much of the encaustic paint still remains, animating the face and hair.

- Broken hand was fitted into the socket and probably held an attribute; she may have been a goddess.

Context: She is named for the peplos, thought to be one of the four traditional garments she is wearing.

Theory

- Recent theory proposes that she is the goddess, either Athena or Artemis; the figure is now missing arrows and a bow in her hand, and she may have worn a metal diadem on her head.

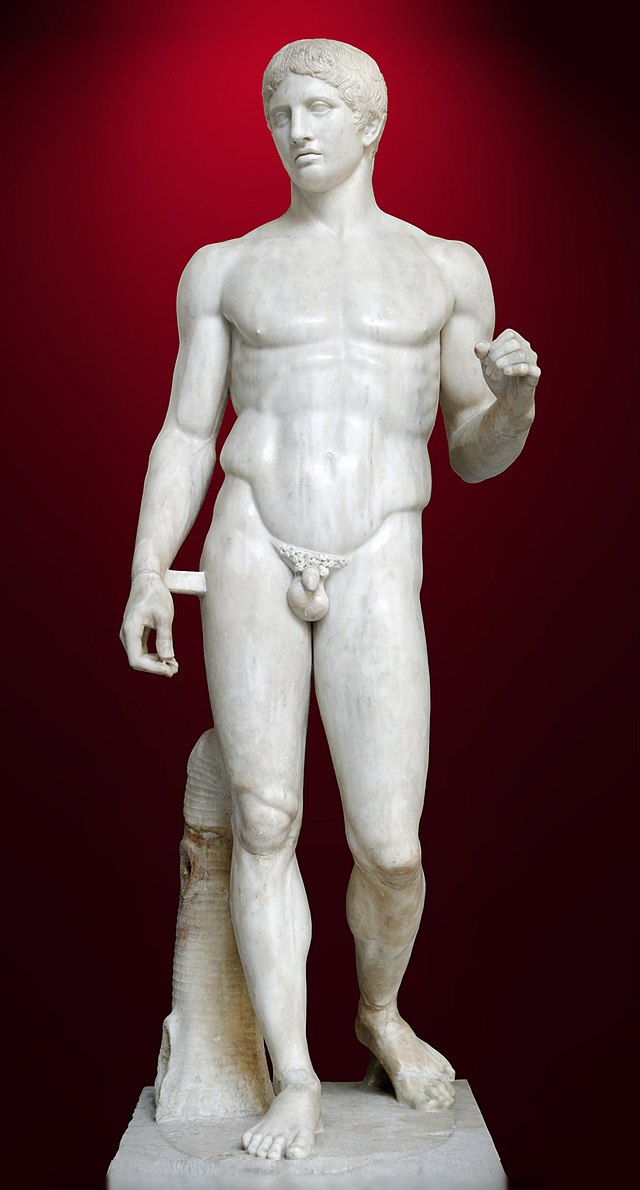

➼ Doryphoros (Spear Bearer)

Details

- A sculpture of Polykleitos

- original: c. 450–440 B.C.E.

- A Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze original,

- Found in National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Form

- Blocky solidity.

- Closed stance.

- Broad shoulders, thick torso, muscular body.

- Idealized body; contrapposto.

- Body is both tense and relaxed: left arm and right leg are relaxed, right arm and left leg are tense.

Content

- Warrior and athlete.

- Hand once held a spear.

- Movement is restrained; ideal Spartan body.

- Averted gaze; he does not recognize the viewer’s admiration.

- Contemplative gaze.

Context: Represents Polykleitos’s ideal masculine figure.

History

- Marble Roman copy of a bronze Greek original.

- Found in Pompeii in a place for athletic training, perhaps for inspiration for athletes.

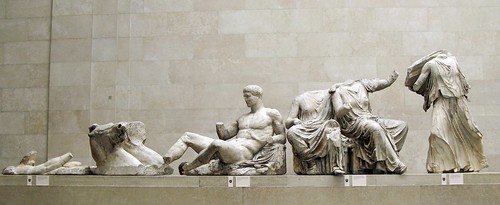

➼ Helios, Horses, and Dionysus (Heracles?)

Details

- c. 438–432 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in British Museum, London

Form

- Greek Classical art; contrapposto.

- Figures seated in the left-hand corner of the east pediment of the Parthenon

- Sculptures comfortably sit in the triangular space of the pediment.

Function

- Part of the east pediment of the Parthenon.

- This grouping contains figures who are present at the birth of Athena, which is the main topic at the center of pediment—now lost.

Content

- On the left, the sun god, Helios, bringing up the dawn with his horses; the male nude is Dionysus, god of wine, and he is lounging.

- Two seated figures may be the goddesses Demeter and Persephone, reacting to the birth of Athena.

Context

- Part of the Parthenon sculptures, also called the Elgin Marbles.

- Phidias acted as the chief sculptor of the workshop.

➼ Plaque of the Ergastines

Details

- c. 447–438 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form

- Isocephalism: the tradition of depicting heads of figures on the same level.

- Figures stand in contrapposto.

- Carved in high relief, which reflects placement; the more three-dimensional the relief, the better it could be seen from below.

Content: Six ergastines, young women in charge of weaving Athena’s peplos, are greeted by two priests.

Context

- Part of a frieze from the Parthenon that depicts some 360 figures.

- Frieze: a horizontal band of sculpture

- Scene from the Panathenaic Frieze depicting the Panathenaic Procession, held every four years to honor Athena.

- Panathenaic Way: a ceremonial road for a procession built to honor Athena during a festival

- This is the first time in Greek art that human events are depicted on a temple.

- The scene contains a religious procession of women dressed in contemporary drapery and acting nobly.

- The procession began at the Dipylon Gate, passed through the agora, and ended at the Parthenon.

- Athenians placed new peplos on an ancient statue of Athena.

Theory: Not the Panathenaic procession but the story of the legendary Athenian king Erechtheus, who sacrificed one of his daughters to save the city of Athens; told to do so by the Oracle of Delphi.

➼ Victory Adjusting Her Sandal

Details

- From the Temple of Athena Nike

- c. 410 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in Acropolis Museum, Athens

- Nike: ancient Greek goddess of victory

Form

- Graceful winged figure modeled in high relief.

- Deeply incised drapery lines reveal body; wet drapery.

Context

- Part of the balustrade on the Temple of Athena Nike, a war monument.

- One of many figures on the balustrade; not a continuous narrative but a sequence of independent scenes.

- The importance of military victories was stressed in the images on the Acropolis.

➼ Grave Stele of Hegeso

Details

- Attributed to Kallimachos

- c. 410 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble and paint

- Found in National Archaeological Museum, Athens

- Stele: an upright stone slab used to mark a grave or a site

Form

- Classical period of Greek art.

- Use of contrapposto in the standing figure.

- Jewelry painted in, not visible.

- Architectural framework.

- Text includes name of the deceased.

Function

- Grave marker.

- In Geometric and Archaic periods, Greeks used kraters and kouroi to mark graves; in the Classical period, stelae were used.

Content

- Commemorates the death of Hegeso; an inscription identifies her and her father.

- Genre scene is that Hegeso examines a piece of jewelry from a jewelry box handed to her by a standing servant; may represent her dowry.

- Standing figure has a lower social station, placed before a seated figure.

Context

- Erected in the Dipylon cemetery in Athens.

- Attributed to the sculptor Kallimachos.

➼ Winged Victory of Samothrace

Details

- Hellenistic Greek

- c. 190 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form

- Monumental figure.

- Dramatic twist and contrapposto of the torso.

- Wet drapery look imitates water playing on the wet body.

- Illusion of wind on the body.

Function: Meant to sit on a fountain representing a figurehead on a boat; the fountain would splash water around the figure.

Content

- Large heroic figure of Nike placed above the marble prow of a naval vessel.

- Nike is wearing several garments, some of which are folded inside out to show the force of the wind.

- Nike may have held a trumpet, wreath, or fillet in her right hand. However, the hand found in Samothrace in 1950 has an open palm and two outstretched fingers, indicating that she was simply greeting.

Context

- Probably made to commemorate a naval victory in 191 B.C.E.; Nike is the goddess of victory.

- The boat at the base is an ancient battleship with oar boxes and traces of a ram.

History

- Found in 1863 in situ on Samothrace.

- Reassembled in the Louvre Museum in Paris and placed at the top of a grand staircase.

- Only one wing was found; the other is a mirror image.

- Only one breast was found; the other is a reconstruction.

- The right hand has been found, but it cannot be attached because no arms have been found.

➼ Athena, from the Great Altar of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon

Details

- Hellenistic Greek

- c. 175 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in Pergamon Museum, Berlin

- Athena: Greek goddess of war and wisdom; patron of Athens

- Zeus: King of the ancient Greek gods; known as Jupiter to the Romans; god of the sky and weather

Form

- Deeply carved figures overlap one another; masterful handling of spatial illusion; figures break into the viewer’s space from the frieze.

- Dramatic intensity of figures and movement; heroic musculature.

Function

- Gigantomachy on the base of the Pergamon Altar illustrates the victories of the goddess Athena, who is worshipped at the altar.

- Gigantomachy: a mythical ancient Greek war between the giants and the Olympian gods

Content

- Describes the battle between the gods and the giants; the giants, depicted as helpless, are dragged up the stairs to worship the gods.

- Athena grabs Alkyoneos by the hair and drags him up the stair to worship Zeus.

- Nike, on the right, crowns Athena in victory.

- Gaia, the earth goddess, looks on in horror and pleads for the fate of her sons, the giants.

Context

- The gods’ victory over the giants offers a parallel to Alexander the Great’s defeat of the Persians.

- Also acts as an allegory of a Greek military victory by Eumenes II.

➼ Seated Boxer

Details

- Hellenistic Greek

- c. 100 B.C.E.

- Made up of bronze

- Found in National Roman Museum, Rome

Form

- Older man, past his prime, looks defeated.

- Smashed nose; lips sunken in suggesting broken teeth.

- Cauliflower ears.

- Nude fighter; hands wrapped in leather bands.

- Figure evinces sadness, stoicism and determination.

Function: May have been a good luck charm for athletes; evidence of toes worn away from being touched.

Materials

- Rare surviving Hellenistic bronze.

- Blood, denoted in copper, drips from his face and onto his right arm and thigh.

- Copper used to highlight his lips and nipples, the straps on his leather gloves, and the wounds on his head.

Context

- May have been part of a group or perhaps a single sculpture, the head turned to face an unseen opponent.

- Found in a Roman bath in Rome.

➼ Athenian Agora

Details

- Archaic through Hellenistic Greek

- 600–150 B.C.E.

- Found in Athens, Greece

- Agora: a public plaza in a Greek city where commercial, religious, and societal activities are conducted

Function

- A plaza at the base of the Acropolis in Athens with commercial, civic, religious, and social buildings where ceremonies took place.

- Setting for the Panathenaic Festival, ceremonies, and parades to honor Athena.

- The Panathenaic Way cuts through along a hilly terrain from the northwestern to the southeastern corners.

Content

- Bouleuterion: a chamber used by a council of 500 citizens, called a boule, who was chosen by lot to serve for one year.

- Tholos: a round structure manned by a group of senators 24 hours a day for emergency meetings; served as a dining hall where the prytaneis (executives) of the boule often met.

- Stoas: Covered walkway with columns on one side and a wall on the other.

➼ Parthenon

Details

- By Iktinos

- From The Parthenon

- 447–410 B.C.E.

- Found in Athens, Greece

Form

- Greek predilection for algebra and geometry is omnipresent in the design of this building: parts can be expressed as x = 2y + 1; thus, there are 17 columns on the side (x) and 8 columns in the front (y), and the ratio of the length to the width is 9:4. Proportions are the same for the cella.

- Unusually light interior had two windows in the cella.

- The façade floor curves upward in the center to drain rainwater and prevent sagging at the ends.

- Since the end columns are surrounded by light, they are thicker to match the others.

- Ionic elements in a Doric temple: the rear room contains Ionic capitals, and the frieze on interior is Ionic.

Function

- Interior built to house a massive statue of Athena, to whom the building was dedicated; also included the treasure of the Delian League.

- The statue, made of gold and ivory over a wooden core, no longer exists.

Context

- Constructed under the leadership of Pericles after the Persian sack of Athens in 480 B.C.E. destroyed the original acropolis.

- Pericles used the extra funds in the Persian war treasury to build the Acropolis; Greek allies were furious that the funds were not returned to them.

History

- Built as a Greek temple dedicated to Athena, the patroness of Athens.

- According to the story, Athena and Poseidon vied for control over Athens and offered gifts to the populace to entice them.

- Poseidon made saltwater spring from the ground on the Acropolis. –Athena made an olive tree grow on the site.

- The Erechtheum, a temple near the Parthenon, houses Poseidon's trident marks, the salt water well, and the sacred olive tree.

- After the Greek period, the Parthenon became a Greek Orthodox church and then a Roman Catholic Mary church.

- In the Islamic period, it was converted to a mosque.

- Destroyed by the Venetians in an attack against the Turks.

- Lord Elgin took half the sculptures to England in the nineteenth century.

➼ Temple of Athena Nike

Details

- By Kallikrates

- From Temple of Athena Nike

- 427–424 B.C.E.

- Made up of marble

- Found in Athens, Greece

Form

- Amphiprostyle: having four columns in the front and four in the back.

- Ionic temple.

Function

- Built to commemorate the Greek victory over the Persians in the Battle of Marathon; Nike is the goddess of victory.

- Once contained a figure of Nike inside.

Context

- Many images of victory on the temple.

- Cf. Victory adjusting her sandal sculpted on a balustrade or railing that once framed the building.

➼ Great Altar of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon

Details

- From Asia Minor (present-day Turkey) Hellenistic Greece

- c. 175 B.C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Pergamon Museum, Berlin

Form

- Altar is on an elevated platform at the top of a dramatic flight of stairs.

- A frieze 7.5 feet high and more than 400 feet long wraps around the monument.

- Ionic columns frame the monument.

Function

- Altar dedicated to Zeus and Athena.

- Cf. Athena on the gigantomachy around the base of the altar.

Context

- Conscious effort to be in dialogue with the Panathenatic frieze on the Parthenon.

- Parallels made between the Pergamon victories over the barbarians in a recent war, Alexander the Great’s defeat of the Persians, and the gods’ defeat of the giants in mythology.

➼ Niobides Krater

Details

- Niobid Painter

- Classical Greek

- 460–450 B.C.E.

- Made of clay, red-figure technique with white highlights

- Found in Louvre, Paris

Form

- First time in vase painting that isocephalism (the tradition of depicting heads of figures on the same level) has been jettisoned.

- May have been the influence of wall paintings, although almost no Greek wall paintings survive.

- Written sources detail how numerous figures were placed at various levels in complex compositions.

Technique: Red figure ware

Function: Ceremonial krater; practical kraters were used for mixing water and wine or storing liquids.

Context

- Called the Niobides Krater because the killing of Niobe’s children is depicted on one side.

- Niobe, who had seven sons and seven daughters, bragged about her fertility to the god Leto, who had only two children.

- Leto’s two children, Apollo and Artemis, sought revenge by killing Niobid’s fourteen.

- Niobid is punished for her hubris.

- Niobe’s children are slaughtered.

- On the other side of the vase, the story is the subject of scholarly debate.

- It may depict Herakles in the center with heroes in arms and Athena on the left.

- Marathon's warriors may be praying to Herakles for protection in an upcoming battle.

History: Found in Orvieto, Italy; many Greek vases found in Etruscan tombs.

➼ Alexander Mosaic

Details

- From the House of Faun, Republican Roman copy of c. 100 B.C.E.

- A mosaic

- Found in National Archaeological Museum, Naples

- Mosaic: a decoration using pieces of stone, marble, or colored glass, called tesserae, that are cemented to a wall or a floor

Form

- Crowded with nervous excitement.

- Extremely complex interweaving of figures; spatial illusionism through foreshortening, chiaroscuro, reflection in shield.

Technique

- Use of tesserae instead of previously used pebbles.

- Tesserae allow for greater flexibility and more complex compositions and shadings.

Function: Roman floor mosaic, found in a house in Pompeii, based on an original Greek mural (?) painting.

Content

- Alexander, at left: does not wear a helmet, showing his bravery.

- Alexander pierces the body of an enemy with his spear without so much as a glance at his victim.

- Alexander’s widened eye is trained on Darius.

- Darius, in center right on chariot: horrified, weakly cedes the victory; his charioteer commands the horses to make their escape.

- Darius looks stunned as his brother, Oxyanthres, is stabbed, the brother portrayed here as sacrificing himself to save the king.

- The dying man’s right hand is still gripping his weapon, as though he wished to pull it out of his body, but his body is already collapsing onto the bloody corpse of his black horse.

Theories

- Perhaps a copy of a mural made by Piloxenos of Eretria for King Cassander.

- Perhaps made by Helen of Egypt, one of the few female Greek artists whose name has come down to us.

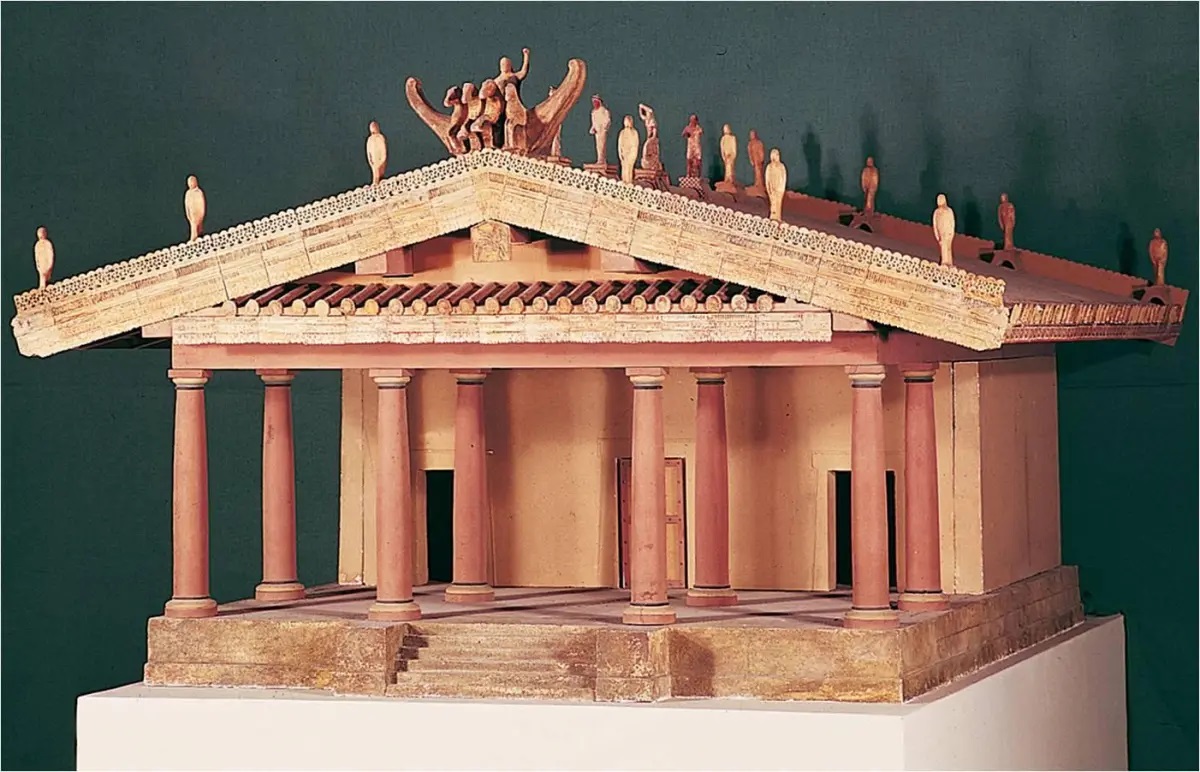

➼ Temple of Minerva

Details

- 510–500 B.C.E.

- Made of mud brick or tufa (volcanic rock) and wood,

- Found in Veii (near Rome), Italy

Form

- Little architecture survives; this model is drawn from descriptions by Vitruvius, a Roman architect of the first century B.C.E.

- Temple raised on a podium; defined visible entrance.

- Deep porch places doorways away from the steps.

Function: Temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva, the Etruscan equivalent to the Greek Athena.

Materials: Temple made of mud brick and wood, perishable materials.

Context

- Steps in front direct attention to the deep porch; entrances emphasized.

- Three doors represent three gods; the interior divided into three spaces.

- Etruscan variation of Greek capitals, called the Tuscan order.

- Tuscan order: an order of ancient architecture featuring slender, smooth columns that sit on simple bases; no carvings on the frieze or in the capitals

- Inspired by Greek architecture, but different:

- Columns are unfluted and made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

- Pediments are made of wood and contain no sculpture, as in Greece.

- Etruscan columns were spaced further apart than Greek columns because they were made of lighter material.

- Etruscans used sculptures made of terra cotta rather than stone on their roofs; columns are unfluted, made of wood, not marble as in Greece.

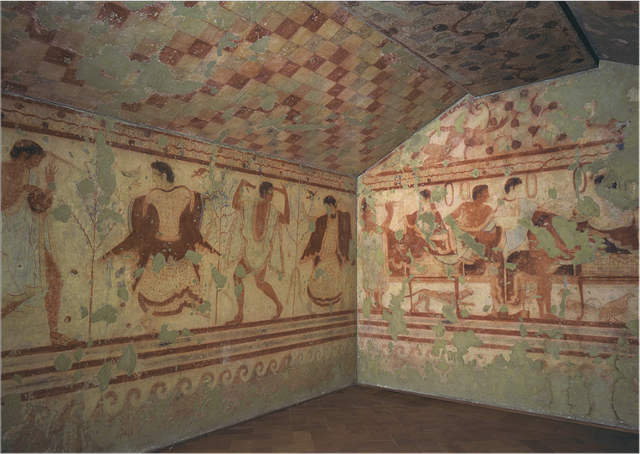

➼ Tomb of the Triclinium

Details

- c. 480–470 B.C.E.

- Made of tufa and fresco

- Found in Tarquinia, Italy

- Triclinium: a dining table in ancient Rome that has a couch on three sides for reclining at meals

Form

- Ancient convention of men painted in darker colors than women.

- Polychrome checkerboard pattern on ceiling; circles may symbolize time; pattern may reflect motifs on fabric tents erected for funeral banquets.

Function: Painted tomb in an Etruscan necropolis.

Content

- Funerals seen as moments in which to celebrate the life of the deceased.

- Dancing figures play musical instruments in a festive celebration of the dead.

- Trees spring up between the main figures, and shrubbery grows beneath the reclining couches—perhaps suggesting a rural setting.

Context

- Banqueting couples recline while eating in the ancient manner.

- Named after a triclinium, an ancient Roman dining table, which appears in the fresco.

➼ Sarcophagus of the Spouses

Details

- c. 520 B.C.E.

- Made of terra cotta,

- Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

- Full-length portraits.

- Great concentration on the upper bodies, less on the legs.

- Bodies make an unnatural L-shape at the waist.

- Broad shoulders, knotted hair, and simple anatomical details.

Function: Sarcophagus of a married couple, whose ashes were placed inside, or perhaps a large urn used for the ashes of the dead.

Technique: Large terra cotta construction made in four separate pieces and joined together.

- Terra cotta: a hard ceramic clay used for building or for making pottery

Content

- Both once held objects in their hands—perhaps the man held an egg to symbolize life after death; other theories suggest the woman is holding a bottle of perfume or a pomegranate.

- The couple reclines against wineskins that act as cushions; the wineskins allude to the ceremony of sharing wine at funerary rituals.

Context

- Depicts the ancient tradition of reclining while eating; men and women ate together, unlike in ancient Greece.

- Symbiotic relationship, the man has a protective arm around the woman and the woman feeds the man, reflecting the high standing women had in Etruscan society.

➼ Apollo from Veii

Details

- Vulca — the master sculptor.

- c. 510 B.C.E.

- Made of terra cotta

- Found in Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

Form

- Figure has spirit, strides quickly forward.

- Archaic Greek smile.

- Meant to be seen from below.

- Tightly fitting garment.

- Hair in knots, dangles down around shoulders.

- Originally brightly painted.

Materials: Masterpiece of terra cotta casting.

Context

- Unlike Greek sculpture, which appears in pediments and is made of stone, Etruscans prefer terra cotta figures that are mounted on roof lines.

- One of four large figures that once stood on the roof of the temple at Veii.

- Part of a scene from Greek mythology involving the third labor of Hercules; Apollo looks directly at Hercules, an important figure in Etruscan religion.

- May have been carved by Vulcan of Veii, the most famous Etruscan sculptor of the age.

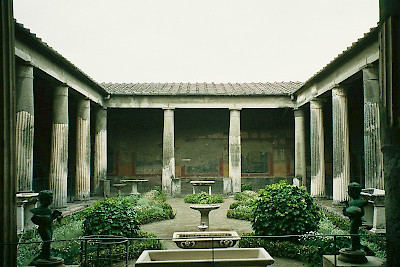

➼ House of Vettii

Details

- From Imperial Roman,

- 2nd century B.C.E.–1st century C.E.

- Rebuilt c. 67–79 C.E.

- Made of cut stone and fresco

- Found in Pompeii, Italy

Form

- Narrow entrance to the home sandwiched between several shops.

- Large reception area called the atrium, which is open to the sky and has a catch basin called an impluvium in the center; rooms called cubicula radiate around the atrium.

- Peristyle garden in rear with fountain, statuary, and more cubicula; this is the private area of the house.

- Axial symmetry of house; someone entering the house can see through to the peristyle garden in the rear.

- Exterior of house lacks windows; interior lighting comes from the atrium and the peristyle.

Function

- Private citizen’s home in Pompeii

- Originally built during the Republic with early imperial additions.

Context

- Two brothers owned the house; both were freedmen who made their money as merchants.

- Extravagant home symbolized the owners’ wealth.

- After the earthquake of 62 A.D., many wealthy Romans left Pompeii, leading to the rise of the “nouveau riche.”

➼ The Colosseum (Flavian Amphitheater)

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 72–80 C.E.

- Made of stone and concrete

- Found in Rome

Function

- Stadium meant for wild and dangerous spectacles—gladiator combat, animal hunts, naval battles—but not, as tradition suggests, religious persecution.

Form

- Accommodated 50,000 spectators.

- Concrete core, brick casing, travertine facing.

- 76 entrances and exits circle the façade.

- Interplay of barrel vaults, groin vaults, arches.

- Façade has engaged columns

- first story is Tuscan,

- second story is Ionic,

- third story is Corinthian, and

- the top story is flattened Corinthian; each thought of as lighter than the order below.

- Flagstaffs: These staffs are the anchors for a retractable canvas roof, called a velarium.

- Velarium: A retractable canvas roof used to protect the crowd on hot days.

- Sand was placed on the floor to absorb the blood; occasionally the sand was dyed red.

- Hypogeum: The subterranean part of an ancient building.

Context

- Real name is the Flavian Amphitheater; the name Colosseum comes from a colossal statue of Nero that used to be adjacent.

- The building illustrates what popular entertainment was like for ancient Romans.

- Entrances and staircases were separated by marble and iron railings to keep the social classes separate; women and the lower classes sat at the top level.

- Much of the marble was pulled off in the Middle Ages and repurposed.

➼ Treasury and Great Temple of Petra, Jordan

Details

- Nabataean Ptolemaic and Roman

- c. 400 B.C.E.–100 C.E.

- Made of cut rock

- Found in Jordan

Context

- Petra was a central city of the Nabataeans, a nomadic people, until Roman occupation in 106 C.E.

- The city was built along a caravan route.

- They buried their dead in the tombs cut out of the sandstone cliffs.

- Five hundred royal tombs in the rock, but no human remains found; burial practices are unknown; tombs are small.

- The city is half built, half carved out of rock. –The city is protected by a narrow canyon entrance.

- The Roman emperor Hadrian visited the site and named it after himself: Hadriane Petra.

Content

- Approached through a monumental gateway, called a propylaeum, and a grand staircase that leads to a colonnade terrace in the lower precincts.

- A second staircase leads to the upper precincts.

- A third staircase leads to the main temple.

Form

- Nabataean concept and Roman features such as Corinthian columns.

- Monuments carved in traditional Nabataean rock-cut cliff walls.

- Lower story influenced by Greek and Roman temples but with unusual features:

- Columns not proportionally spaced.

- Pediment does not cover all columns, only the central four.

- Upper floor: broken pediment with a central tholos.

- Combination of Roman and indigenous traditions.

- Greek, Egyptian, and Assyrian gods on the façade.

- Interior: one central chamber with two flanking smaller rooms.

Function: In reality, it was a tomb, not a “treasury,” as the name implies.

➼ Forum of Trajan

Details

- By Apollodorus of Damascus

- 106–112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

Form

- Large central plaza flanked by stoa-like buildings on each side.

- Originally held an equestrian monument dedicated to Trajan in the center.

Function: Part of a complex that included the Basilica of Ulpia, Trajan’s markets, and the Column of Trajan.

Context: Built with booty collected from Trajan’s victory over the Dacians.

➼ Basilica of Ulpia

Details

- c. 112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

- Basilica: in Roman architecture, a large axially planned building with a nave, side aisles, and apses

Form

- Grand interior space (385 feet by 182 feet) with two apses.

- Nave is spacious and wide.

- Double colonnaded side aisles.

- Second floor had galleries or perhaps clerestory windows.

- Timber roof 80 feet across.

- Basilican structure can be traced back to Greek stoas.

Functional: Law courts held here; apses were a setting for judges.

Context

- Said to have been paid for by Trajan’s spoils taken from the defeat of the Dacians.

- Ulpius was Trajan’s family name.

➼ Trajan Markets

Details

- 106–112 C.E.

- Made of brick and concrete

- Found in Rome, Italy

Form

- Semicircular building held several levels of shops.

- Main space is groin vaulted; barrel vaulted area with the shops.

Function

- Multilevel mall.

- Original market had 150 shops.

Materials: Use of exposed brick indicates a more accepted view of this material, which formerly was thought of as being unsuited to grand public buildings.

➼ Pantheon

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 118–125 C.E.

- Made of concrete with stone facing

- Found Rome, Italy

Form Exterior

- Corinthian-capital porch in front of this building.

- Façade has two pediments, one deeply recessed behind the other; it is difficult to see the second pediment from the street.

Form Interior

- Interior contains a slightly convex floor for water drainage.

- Square panels on floor and in coffers contrast with roundness of walls; circles and squares are a unifying theme.

- Coffers may have been filled with rosette designs to simulate stars.

- Cupola walls are enormously thick: 20 feet at base.

- Thickness of walls is thinned at the top; coffers take some weight pressure off the walls.

- Oculus, 27 feet across, allows for air and sunlight; sun moves across the interior much like a spotlight

- Height of the building equals its width; the building is based on the circle; a hemisphere.

- Walls have seven niches for statues of the gods.

- Triumph of concrete construction.

- Was originally brilliantly decorated.

Function

- Traditional interpretation: it was built as a Roman temple dedicated to all the gods.

- Recent interpretation: it may have been dedicated to a select group of gods and the divine Julius Caesar and/or used for court rituals.

- It is now a Catholic church called Santa Maria Rotonda.

Context

- Inscription on the façade: “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, having been consul three times, built it.”

- The name Pantheon is from the Greek meaning “all the gods” or “common to all the gods.”

- Originally had a large atrium before it; originally built on a high podium; modern Rome has risen up to that level.

- Interior symbolized the vault of the heavens.

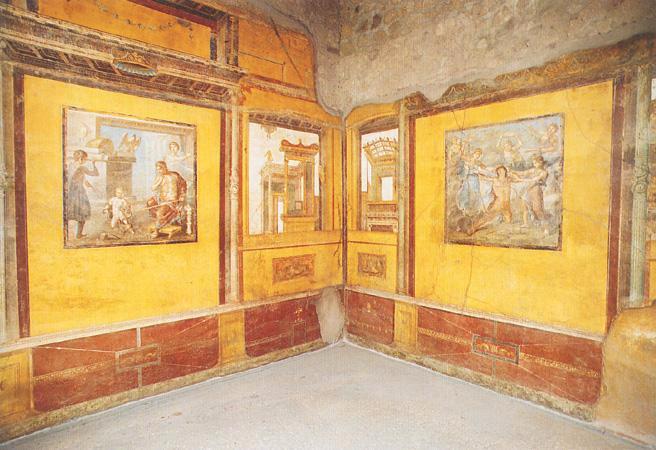

➼ Pentheus Room

Details

- Imperial Roman

- 62–79 C.E.

- fresco

- Foun in Pompeii, Italy

Function

- Triclinium: a dining room in a Roman house.

Context

- Main scene is the death of the Greek hero Pentheus.

- Pentheus opposed the cult of Bacchus and was torn to pieces by women, including his mother, in a Bacchic frenzy; two women are pulling at his hair in this image.

- Punishment of Pentheus is eroticized; central figure with arms outstretched; exposed nakedness of his body.

- Architecture is seen through painted windows; imaginary landscape.

- This painting opens the room with the illusion of windows and a sunny cityscape beyond.

➼ Head of a Roman patrician

Details

- Republican Roman

- c. 75–50 B.C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Museo Torlonia, Rome

Function

- Funerary context; funerary altars adorned with portraits, busts, or reliefs and cinerary urns.

- Tradition of wax portrait masks in funeral processions of the upper class to commemorate their history.

- Portraits housed in family shrines honoring deceased relatives.

Context

- Realism of the portrayal shows the influence of Greek Hellenistic art and late Etruscan art.

- Bulldog-like tenacity of features; overhanging flesh; deep crevices in face.

- Full of experience and wisdom—traits Roman patricians would have desired.

- Features may have been exaggerated by the artist to enhance adherence to Roman Republican virtues such as stoicism, determination, and foresight.

- Busts are mostly of men, often depicted as elderly.

➼ Augustus of Prima Porta

Details

- Imperial Roman

- Early 1st century C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Vatican Museums, Rome

Form

- Contrapposto.

- References Polykleitos’s Doryphoros.

- Characteristic of works depicting Augustus is the part in the hair over the left eye and two locks over the right.

- Heroic, grand, authoritative ruler; over life-size scale.

- Back not carved; figure meant to be placed against a wall.

- Oratorical pose.

Function and Original Context

- Found in the villa of Livia, Augustus’s wife; may have been sculpted to honor him in his lifetime or after his death (Augustus is barefoot like a god, not wearing military boots).

- May have been commissioned by Emperor Tiberius, Livia’s son, whose diplomacy helped secure the return of the eagles; thus it would serve as a commemoration of Augustus and the reign of Tiberius.

Content

- Idealized view of the Roman emperor, not an individualized portrait.

- Confusion between God and man is intentional; in contrast with Roman Republican portraits.

- Standing barefoot indicates he is on sacred ground.

- On his breastplate are a number of gods participating in the return of Roman standards from the Parthians; Pax Romana.

- Breastplate indicates he is a warrior; judges’ robes show him as a civic ruler.

- He may have carried a sword, pointing down, in his left hand.

- His right hand is in a Roman orator pose; perhaps it held laurel branches.

- At base: Cupid on the back of a dolphin—a reference to Augustus’s divine descent from Venus; perhaps also a symbol of Augustus’s naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

- Maybe a copy of a bronze original, which probably did not have the image of Cupid.

➼ Column of Trajan

Details

- 113 C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in Rome

Form

- A 625-foot narrative cycle (128 feet high) wrapped around the column tells the story of Trajan’s defeat of the Dacians; this is the earliest example of this kind of structure.

- Crowded composition.

- Base of the column has an oak wreath, the symbol of victory.

- Low relief; few shadows to cloud what must have been a very difficult object to view in its entirety.

Function

- Visitors who entered the column were meant to wander up the interior spiral staircase to the viewing platform at the top where a heroic nude statue of the emperor was placed.

- Base contains the burial chamber of Trajan and his wife, Plotina, whose ashes were placed in golden urns in the pedestal.

Technique: Roman invention of a tall hollowed out column with an interior spiral staircase.

Content

- 150 episodes, 2,662 figures, 23 registers—continuous narrative.

- Continuous narrative: a work of art that contains several scenes of the same story painted or sculpted in continuous succession

- Scenes on the column depict the preparation for battle, key moments in the Dacian campaign, and many scenes of everyday life

- Trajan appears 58 times in various roles: commander, statesman, ruler, etc.

Context

- Stood in Trajan’s Forum at the far end surrounded by buildings.

- Scholarly debate over the way it was meant to be viewed.

- A viewer would be impressed with Trajan’s accomplishments, including his forum and his markets.

- Two Roman libraries containing Greek and Roman manuscripts flanked the column.

➼ Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus

Details

- Late Imperial Roman

- c. 250 C.E.

- Made of marble

- Found in National Roman Museum, Rome

Form

- Extremely crowded surface with figures piled atop one another; horror vacui.

- Abandonment of classical tradition in favor of a more animated and crowded space.

- Horror vacui: (Latin for a “fear of empty spaces”) a type of artwork in which the entire surface is filled with objects, people, designs, and ornaments in a crowded, sometimes congested way

- Figures lack individuality.

Function: Interment of the dead; rich carving suggests a wealthy patron with a military background.

Technique

- Very deep relief with layers of figures.

- Complexity of composition with deeply carved undercutting.

Content

- Roman army trounces bearded and defeated barbarians.

- Romans appear noble and heroic while the Goths are ugly.

- Romans battling “barbaric” Goths in the Late Imperial period.

- Youthful Roman general appears center top with no weapons, the only Roman with no helmet, indicating that he is invincible and needs no protection; he controls a wild horse with a simple gesture.

Context

- Confusion of battle is suggested by congested composition.

- Rome at war throughout the third century.

- So called because in the seventeenth century it was in Cardinal Ludovisi’s collection in Rome.