neuroscience; week 2; behavioural genetics II

The criminal DNA: the 1920s or the Daily Mail

Were you born a thug? Experiences can make a criminal- but genes are to blame for violent behaviour too, study finds

study questioned 1337 Swedish students about their life experiences

took DNA testing for gene variants MAOA, 5-HTTLPR and BDNF

MAOA breaks down and releases energy in transmitters such as serotonin

¼ men carry less active MAOA variant and among them, those that experienced physical abuse in childhood are more likely to be violent

overall the study found 3 variants interacted with each other, and with conflict and abuse, to increase the likelihood of delinquency

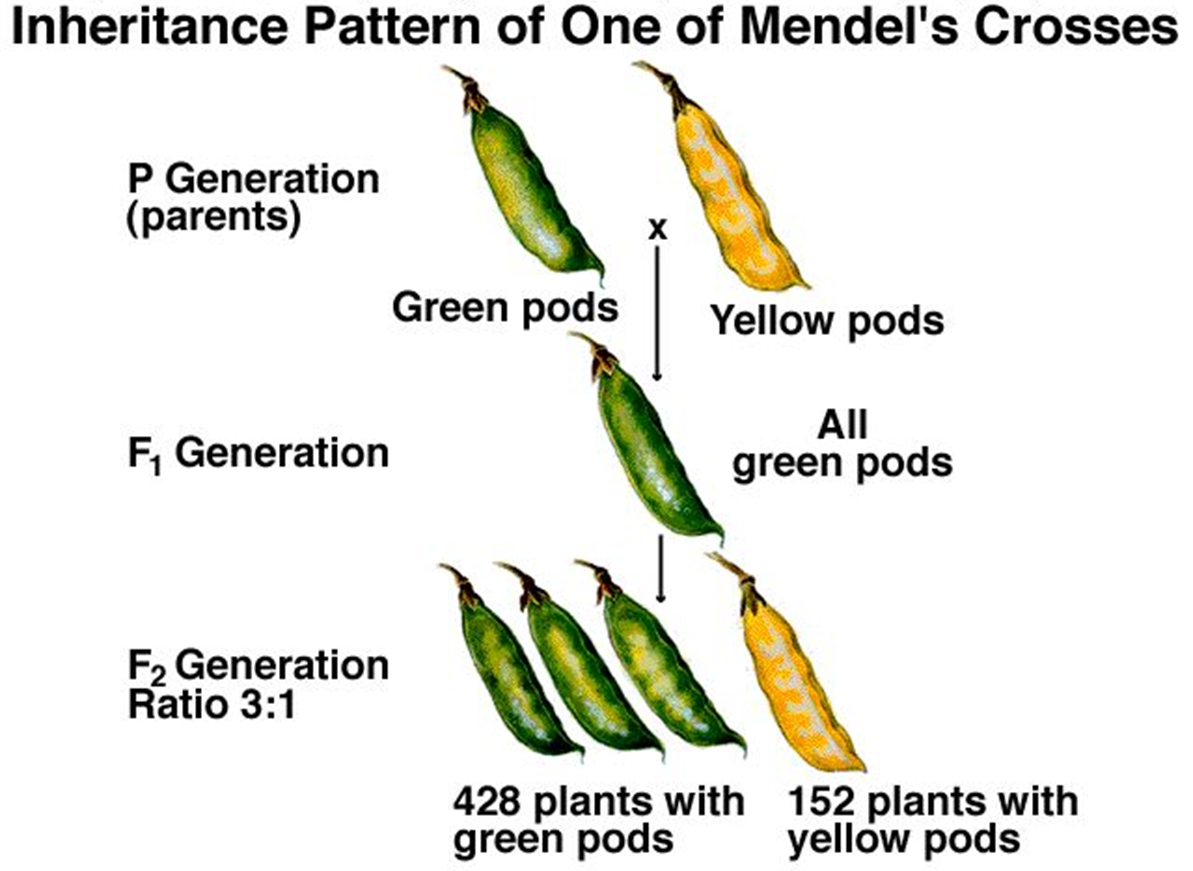

Mendel (1822-84)

Monk that studied dichotomous traits; these are traits which are in one form or another, never in combination

Mendel particularly studied the humble pea plant

the pea plants have pods and the pods can be green or yellow, he bred, experimented and examined the amount of green and yellow pea pods in each generation

started with green pea pods and crossed them with plants that bore yellow at pea pods and then with the second generation of peas they were all green

he bred them together and then he ended up with a ratio for three green pea plants to every one yellow pea plant

Why did this colour ratio of peas occurs? what were the hypothetical constructs at the time?

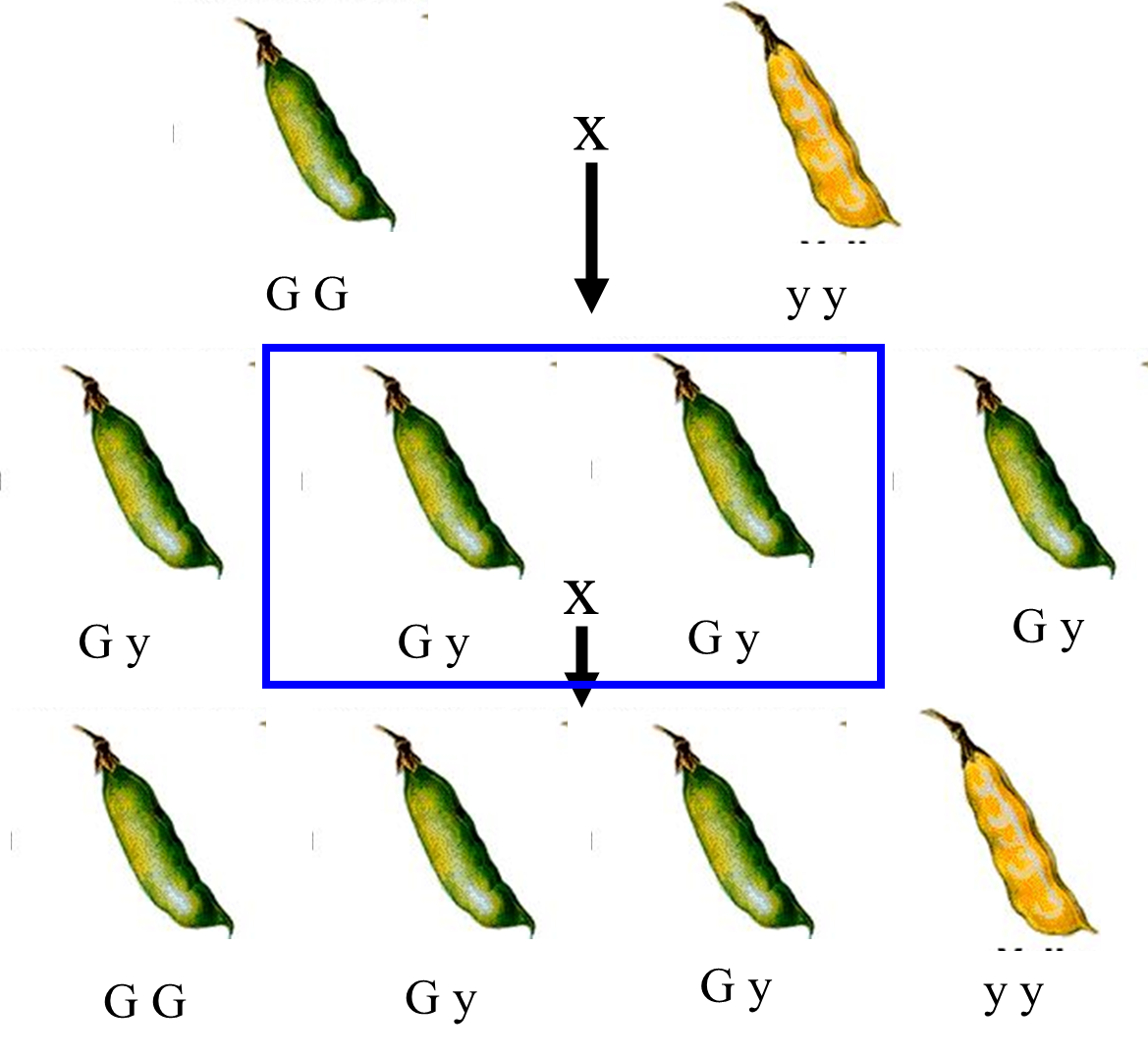

he proposed that each of the next generation of pea plants got one of these letters from each parent pea plant

so it goes from GG and yy → Gy, then the next generation would take one letter from each pea again, however, this COULD result in the pea taking both y’s or both G’s, but most commonly Gy again

one would propose that this is the way that the patterns of inheritance worked

this is what’s called Mendelian inheritance

Terms'

Phenotype – trait e.g. yellow versus green

Genetotype – genetic material (e.g. GG)

Allele – different forms of a gene that control the same trait (G versus y)

Heterozygous: Gy

Homozygous: GG or yy

G is dominant to y

y is recessive to G

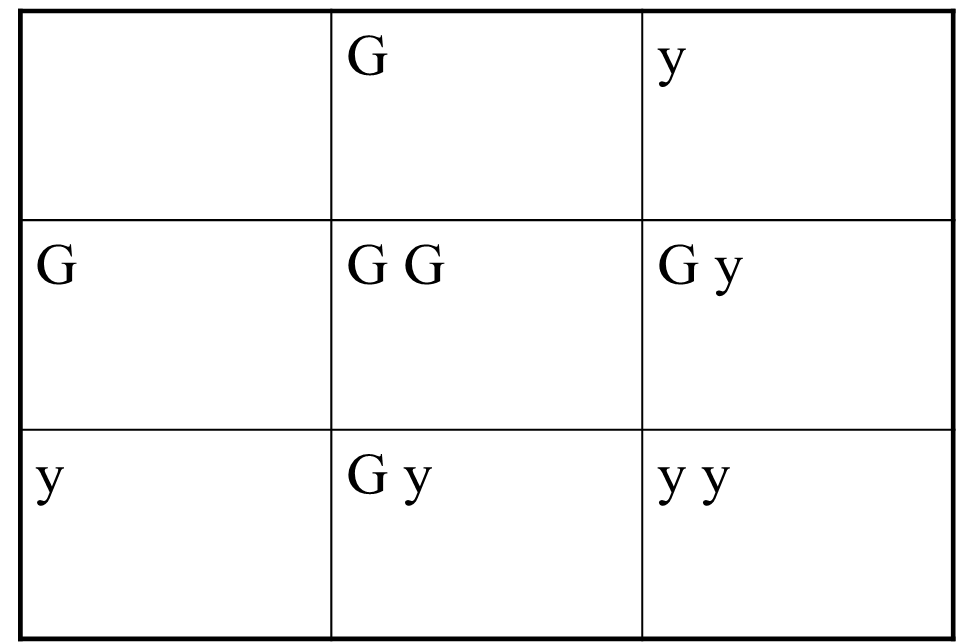

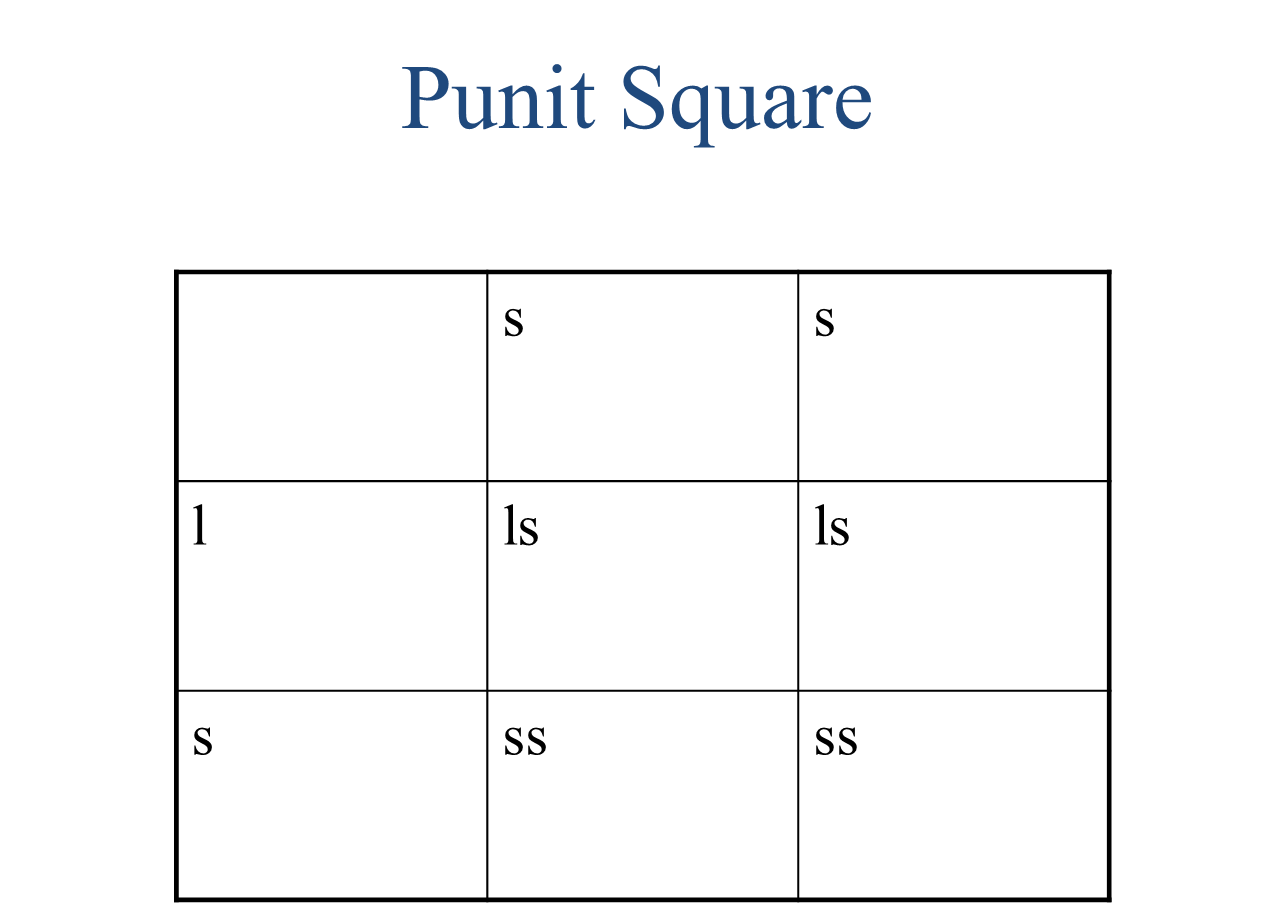

Punit square

one way you can look at the patterns of inheritance and calculate your ratios is by doing a punnet square

this is where you put the alleles of one parent along the top/ the alleles or the other parent down the side, so you can fill in the matrix

Using information about pea plant genetics in regards to psychology

you probably don’t want to know about pea plant genetics when doing a psychology degree, But you might want to know about depression and genes associated with higher incidence of depression

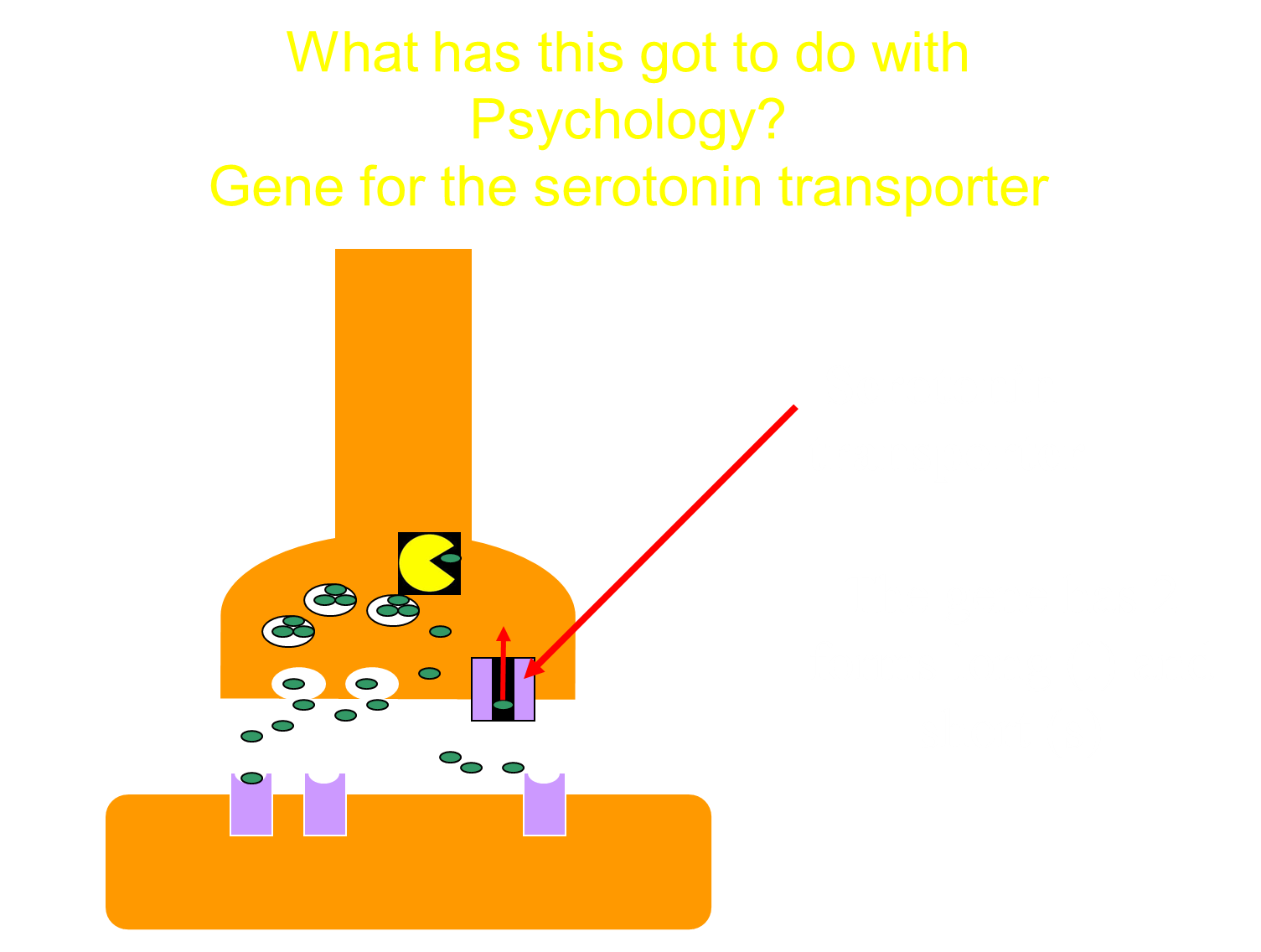

one such gene is the serotonin transporter

The gene for the serotonin transporter has two forms, we can think of those as being alleles; there’s a long and a short form

so if you’ve got the long form, it makes the longer a sort of protonated version of the serotonin transporter and the short form is sort of just a shorter version

they both have different levels of activity in hoovering back up the serotonin not transmitted during the synaptic transmission

SO we’ve got a returning transporter, it can be long (l) or short (s) form, so we might have one parent with two short forms and one parent with a long and a short form

the pattern of inheritance demonstrates that the next generation will be all short form from one parent, long form and short form for another parent

in this case, there isn’t a pattern of one being dominant and one being recessive, the effects/ two alleles of the same gene are additive (A)

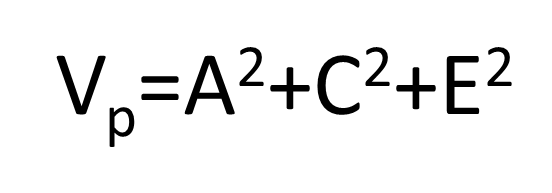

Vp=A2+C2+E2

V is the variance of a trait

A is the ADDIDITVE genetic component

C is the common or “shared” environment

E is the “non-shared” environment

where are genes?

- on chromosomes

Chromosomes

chromosomes are in pairs

chromosomes are made of DNA (Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid)

22 autosomal chromosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes

DNA (Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid)

live sin the nucleus of each cell

What does DNA do?

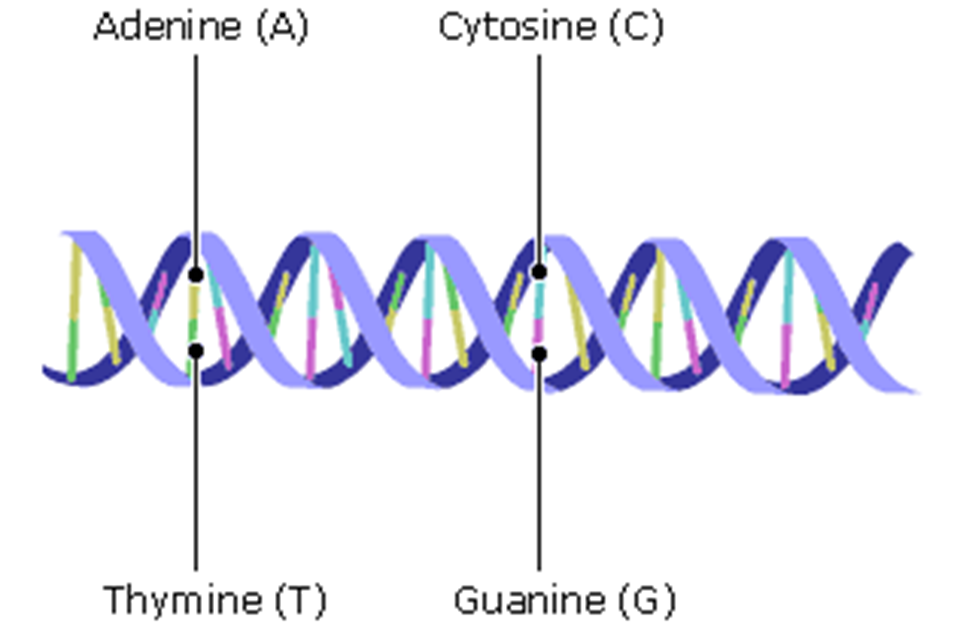

if we zoom in to a strand of DNA, it has a particular double alpha helix structures

it is made of base pairs and, in the case of DNA, there is adenine (A), Thymine (T), Cytosine (C) and Guanine (G), these bases are paired together

the base pair goes across this coil (A always goes to T and C always goes to G)

The DNA structure

allows the DNA to unwind for replication

the structure was discovered by Watson and Crick in the 50s (they got the noble prize)

after the pairs unwind, the spare bases that are sort of lurking about in the cell cycle and bind to the unwound strands of DNA and allows the DNA to replicate

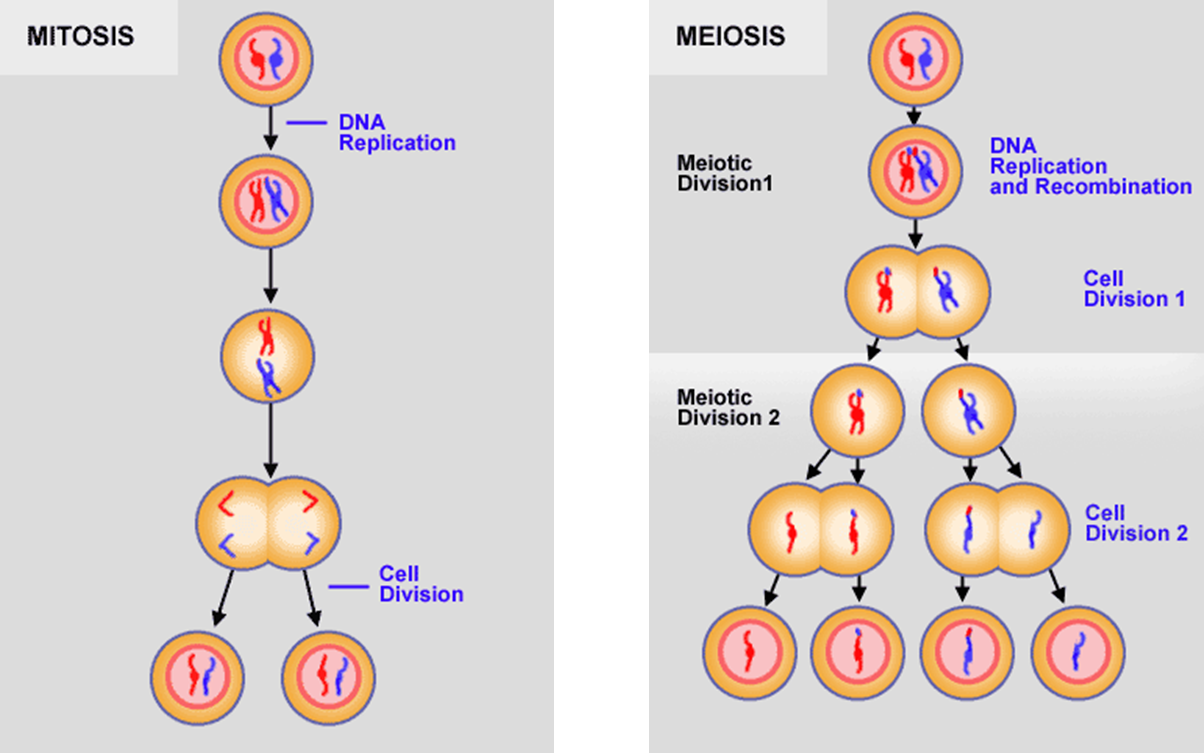

the replication is good because you can have mitosis (where you replicate cell division)

Mitosis and Meiosis

after you undergo mitosis, you can also undergo meiosis

when you undergo meiosis, you end up with cells that have half the amount of DNA and they just have one of the chromosomes in each chromosome pair

the cells on the bottom of here are at the end of meiosis, so these are gametes like sperm or eggs that have half the amount of DNA

Meiosis

meiosis was slightly interesting because this is how the pattern of inheritance arises

so this is why we randomly get one of each of the two chromosomes in the beginnings and then they recombined

the two chromosomes of each pair can sort of cosy up to one each other and this results in this thing called crossing over

so in addition to getting randomly one or the other of each chromosome pair, you can get a bit of jumbling up too

and so this increases the chance of genetic variation of passing it on to the next generation

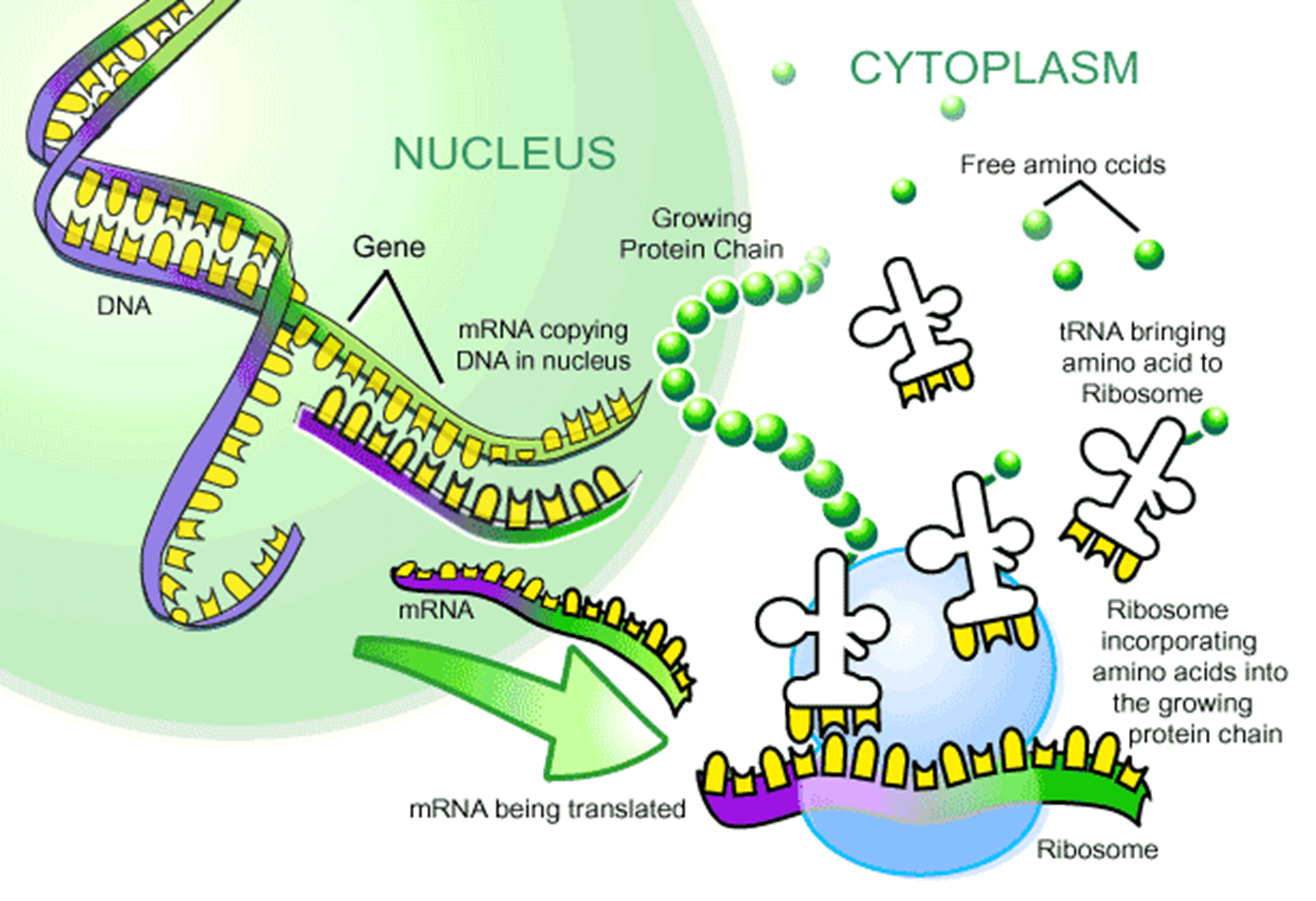

DNA makes protein

because it has got this double alpha helix structure, it can unwind and replicate itself- why do we want this to happen though? To make protein!

The genes gets turned into a protein. The DNA unwinds and then transcribes into a complementary strand of something called messenger RNA (mRNA)

well how does that work then?

so if you go into the nucleus of the cell, the DNA unwinds and then you get the mRNA as a single strand thats complementary to the DNA

then RNA goes on a little journey out of the nucleus into the rest of the cell

the chain of amino acids is actually how you make proteins

What’s RNA?

RNA is a bit like DNA when it exists in like one strand, so doesn’t have two strands like DNA.

The base pairs are slightly different, you get cytosine, guanine, adenine and uracil (c→g, A→U)

DNA and mRNA

it works in codes of three, each letter of three that corresponds to a particular amino acid

each pattenr of three letters correspond to particular amino acids,

thus the DNA can get turned to mRNA in little triplets

and then for encodes a strand of amino acids

what are amino acids?

just the components that proteins are made up of

Tranfer RNA

this has got a complementary triplet

Why are we interested in proteins?

they do lots of things in the brains

for example, transporter proteins or if you’ve got a particular nicotinic receptor gene, then you’re much more likely to be addicted to smoking and find it more difficult to give up

Can you name important proteins for the brain?

Gene for tryptophan hydroxylase

this isn’t the same as the serotonin transporter gene

tryptophan hydroxylase is just the enzyme that makes serotonin

hydroxylase is what’s called the rate limiting enzyme in the reaction that makes serotonin to make all neurotransmitters

the serotonin tryptophan comes in from our diet (much in turkey and eggs) then the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase that turns that into a precursor to serotonin, then it finally gets turned into serotonin

an issues with this enzyme means that you wouldn’t be able to make as much serotonin

Zhang et al 2005 found there was a mutant form of the trait of an hydroxylase gene

Gene for the serotonin transporter

the gene can be long or short so it occupies a different length of the DNA, thus the long form is longer than the short form

the long and short forms have different levels of activity at hoovering up the serotonin

people believed that the short form was more related to depressive symptoms than the long form, but there are studies where it isn’t linked at all,

could be psychological measures of depression are inaccurate or could be that the link doesn’t exist

a solution for this is a brain scanner:

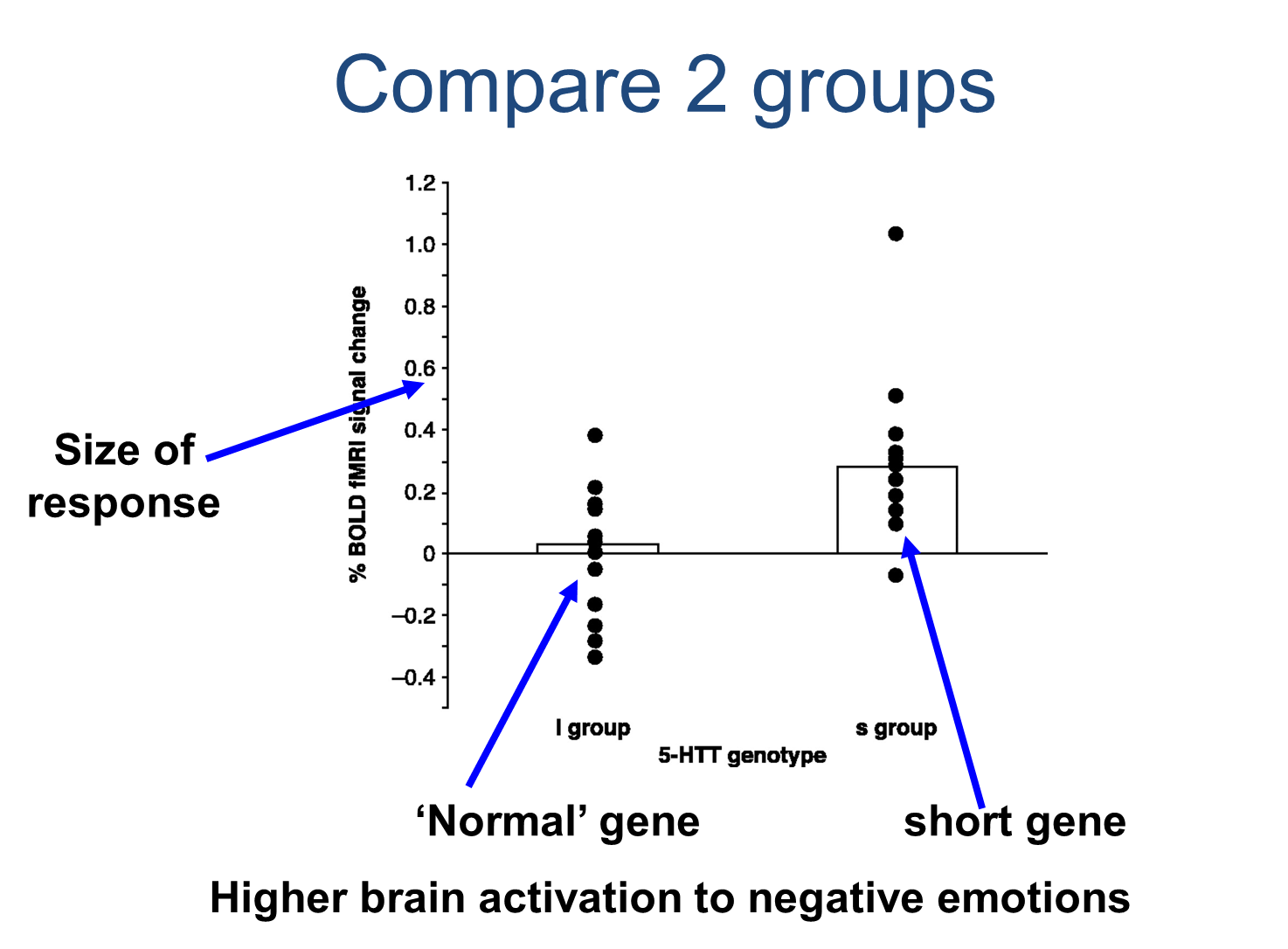

Daniel Weinberg took people with long and short forms of alien transporter and saw what was going on in their brains and to see if there’s any risk factors he could find for the serotonin transporter, so he measured whether they had a long or short form of transport and none of them had a diagnosis of depression, even when they had two short forms of the transporter. He then got people to judge angry and afraid faces (aquaman’s classic faces) and he looked at the response of the amygdala using fMRI. Angry enough red faces, we can get a response in the amygdala

then we look at the toning transporter genotype, 5-HTT is a chemical name for serotonin

the short route had two short forms of the gene, the short group has a big response in the amygdala and the two long forms of the gene get a much lower response in the amygdala to a fearful or afraid face

Short form of serotonin transporter gene makes the brain “over-respond” to negative emotions, their amygdala is much more reactive,

if you’ve got a brain that’s naturally responding more to negative stimuli overtime, that could lead to depression somehow, however, none of the people in this study have depression at all, so how is the short form related to actual depression then?

Mutation of the tryptophan hydroxylase gene

In Vitro cells with this gene make 80% less serotonin than cells with normal gene

and so Zhang et al 2005 took some people with depression and some control subjects, found that in 87 people with depression, 9 of the people had the mutant form of the TH gene and in the 219 control subjects, 3 of them had it

so quite rare out of 300 people, but 3 times as many people had it in the depressed group

of the 3 subjects in the control group with the mutant form, they had anxiety, alcoholism, family history of mental health problems

mutant form seems to result in mental health problems BUT many people who are clinically depressed do not have the mutant form

so how can the short form be related to actual depression then?

it might be something in the environment, if it wasn’t anything to do with the environment related to the depression

Brown (1993)

women with depression and they showed that depressed patients were much more likely to have severe stress in the previous year before a depression diagnosis than control participants.

people without depression were 30% more likely to have had a severe stressful like event in the previous year

those with depression were 84% likely to have had severe stress in the previous year and we can see here some people having stress and are not depressed

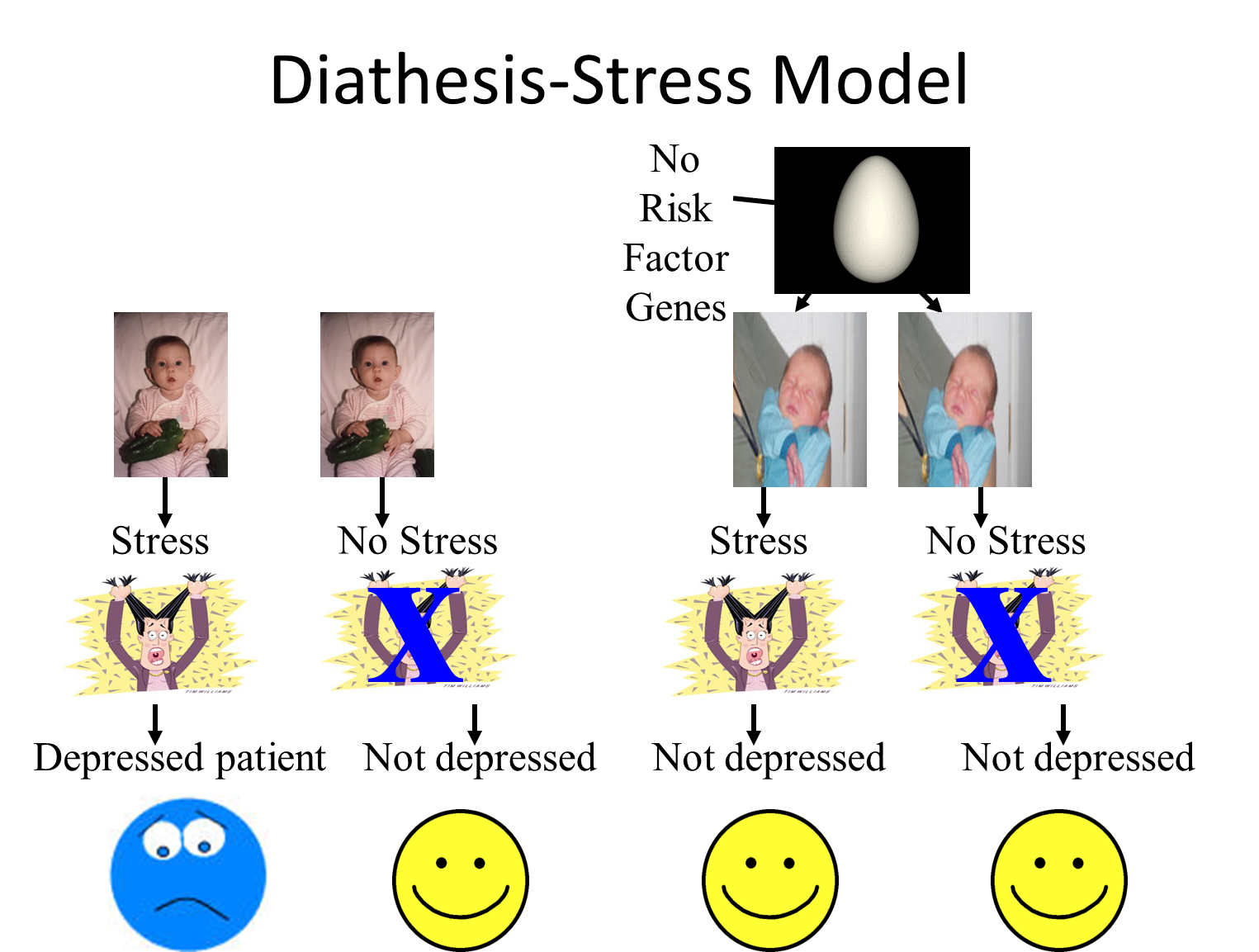

Diathesis-stress model

Caspi et al 2003

Subjects from Dunedin multidisciplinary Health and development study, 1037 subjects, Age 26.

Measured stressful events

Divided subjects into groups based on forms of serotonin transporter gene.

Measured depressive symptoms.

results:

No difference in number of stressful events between genetic groups.

Depressive symptoms:

Number of stress full life events: non significant

Genotype: non-significant

Interaction: Highly significant!

Caspi study summary

5HT-T gene short (s) and long (l),

more short forms you have more likely to be depressed (ss versus ls versus ll)

BUT only when combined with stressful life events

(G X E interaction)

Gene x Environment interaction

Reading

Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene

In a prospective-longitudinal study, we tested why stressful experiences lead to depression in only some people. A functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene was found to moderate the influence of stressful life events on depression. Individuals with one or two copies of the short allele of the 5-HTT promoter polymorphism exhibited more depressive symptoms, diagnosable depression, and suicidality in relation to stressful life events than individuals homozygous for the long allele. This epidemiological study thus provides evidence of a gene-by-environment interaction, in which an individual’s response to environmental insults is moderated by his or her genetic makeup.

Depression is among the top five leading causes of disability and disease burden throughout the world.

Diathesis-stress theories of depression:

predict that individuals’ sensitivity to stressful events depends on their genetic makeup.

research shows the risk of depression after a stressful event is elevated for people at high genetic risk and diminished for those at low genetic risk.

However, whether specific genes exacerbate or buffer the effect of stressful life events on depression is unknown.

In this study, a functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) was used to characterize genetic vulnerability to depression and to test whether 5-HTT gene variation moderates the influence of life stress on depression.

The serotonin system

provides a source of candidate genes for depression, because this system is the target of selective serotonin reuptake–inhibitor drugs that are effective in treating depression.

The serotonin transporter has received particular attention because it is involved in the reuptake of serotonin at brain synapses.

The promoter activity of the 5-HTT gene

located on 17q11.2

is modified by sequence elements within the proximal 5 regulatory region

this is designated the 5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR).

The short (“s”) allele in the 5-HTTLPR is associated with lower transcriptional efficiency of the promoter compared with the long (“l”) allele. The 5-HTT gene is not directly associated with depression, but could moderate the serotonergic response to stress.

Three experiments suggest this.

First, in mice with disrupted 5-HTT, homozygous and heterozygous (5-HTT–/– and /–) strains exhibited more fearful behaviour and greater increases in the stress hormone (plasma) adrenocorticotropin in response to stress compared to homozygous (5-HTT / ) controls, but in the absence of stress no differences related to genotype were observed.

Second, in rhesus macaques, whose length variation of the 5-HTTLPR is analogous to humans, the short allele is associated with decreased serotonergic function among monkeys reared in stressful conditions but not among normally reared monkeys.

Third, human neuroimaging research suggests that the stress response is mediated by variations in the 5-HTTLPR. Humans with 1 or 2 copies of the s allele exhibit greater amygdala neuronal activity to fearful stimuli compared to individuals homozygous for the l allele.

Taken together, these findings suggest the hypothesis that variations in the 5-HTT gene moderate psycho pathological reactions to stressful experiences.

We tested this G E hypothesis among members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study.

This representative birth cohort of 1037 children (52% male) has been assessed at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, and 21 and was virtually intact (96%) at the age of 26 years.

A total of 847 Caucasian non-Maori study members, without stratification confounds, were divided into three groups on the basis of their 5-HTTLPR genotype (11):

those with two copies of the s allele (s/s homozygotes; n 147; 17%),

those with one copy of the s allele (s/l heterozygotes; n 435; 51%),

those with two copies of the l allele (l/l homozygotes; n 265; 31%).

There was no difference in genotype frequencies between the sexes.

Stressful life events occurring after the 21st birthday and before the 26th birthday were assessed with the aid of a life-history calendar, a highly reliable method for ascertaining life-event histories.

Of the 14 events (including employment, financial, housing, health, and relationship stressors) what were the rates of stressful life events?

30% of study members experienced no stressful life events;

25% experienced one event;

20%, two events;

11%, three events;

15%, four or more events.

There were no significant differences between the three genotype groups in the number of life events they experienced suggesting that 5-HTTLPR genotype did not influence exposure to stressful life events.

what did the researchers do to assess depression?

Study members were assessed for past-year depression at age 26 with the use of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, which yields a quantitative measure of depressive symptoms and a categorical diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to DSM-IV criteria.

17% of study members (58% female versus 42% male) met criteria for a past-year major depressive episode, which is comparable to age and sex prevalence rates observed in U.S. epidemiological studies.

In addition, 3% of the study members reported past-year suicide attempts or recurrent thoughts about suicide in the context of a depressive episode.

We also collected informant reports about symptoms of depression for 96% of study members at age 26 by mailing a brief questionnaire to persons nominated by each study member as “someone who knows you well.”

We used a moderated regression frame work (22), with sex as a covariate, to test the association between depression and (i) 5 HTTLPR genotype, (ii) stressful life events, and (iii) their interaction.

The interaction between 5-HTTLPR and life events

showed that the effect of life events on self reports of depression symptoms at age 26 was significantly stronger among individuals carrying an s allele than among l/l homozygotes.

We further tested whether life events could predict within-individual increases in depression symptoms over time among individuals with an s allele by statistically controlling for the baseline number of depressive symptoms they had before the life events occurred (table S1).

The sig nificant interaction (P 0.05) showed that individuals carrying an s allele whose life events occurred after their 21st birthday experienced increases in depressive symptoms from the age of 21 to 26 years whereas l/l homozygotes did not.

The G Einteraction

showed that stressful life events predicted a diagnosis of major depression among carriers of an s allele but not among l/l homozygotes.

Can life events predict the onset of new diagnosed depression among carriers of an s allele?

The significant interaction showed that life events occurring after their 21st birthdays predicted depression at age 26 among carriers of an s allele who did not have a prior history of depression but did not predict onset of new depression among l/l homozygotes.

Further analyses showed that stressful life events predicted suicide ideation or attempt among individuals carrying an s allele but not among l/l homozygotes.

The hypothesized G E interaction was also significant when we predicted informant reports of age-26 depression, an analysis that ruled out the possibility of self report bias.

The interaction showed that the effect of life events on informant reports of depression was stronger among individuals carrying an s allele than among l/l homozygotes.

what does these analyses outline?

They attest that the 5-HTT gene interacts with life events to predict depression symptoms, an increase in symptoms, depression diagnoses, new-onset diagnoses, suicidality, and an informant’s report of depressed behaviour.

SO what was the point of this report (seriously I hated reading this)?

This evidence that 5-HTTLPR variation moderates the effect of life events on depression does not constitute unambiguous evidence of a G E interaction, because exposure to life events may be influenced by genetic factors; if individuals have a heritable tendency to enter situations where they encounter stressful life events, these events may simply be a genetically saturated marker.

Thus, what we have identified as a gene environment interaction predicting depression could actually reflect a gene “gene” interaction between the 5-HTTLPR and other genes we did not measure.

We reasoned that, if our measure of life events represents merely genetic risk, then life events would interact with 5-HTTLPR even if they occurred after the depression episode.

However, if our measure of life events rep resents environmental stress, then the timing of life events relative to depression must follow cause-effect order and life events that occur after depression should not interact with5-HTTLPRtopostdict depression.

We tested this hypothesis by substituting the age 26 measure of depression with depression assessed in this longitudinal study when study members were 21 and18 years old, before the occurrence of the measured life events between the ages of 21 and 26 years.

Where as the 5-HTTLPR life events interaction predicted depression at the age of 26 years, this same interaction did not postdict depression reported at age 21 nor at the age of 18 years, indicating our finding is a true G E interaction.

If 5-HTT genotype moderates the depressogenic influence of stressful life events, it should moderate the effect of life events that occurred not just in adulthood but also of stressful experiences that occurred in earlier developmental periods.

Based on this hypothesis, we tested whether adult depression was predicted by the interaction between 5 HTTLPR and childhood maltreatment that occurred during the first decade of life.

what did the interaction show about childhood maltreatment and adult depression?

Consistent with the G E hypothesis, the longitudinal prediction from childhood maltreatment to adult depression was significantly moderated by 5-HTTLPR.

The interaction showed (P 0.05) that childhood maltreatment predicted adult depression only among individuals carrying an s allele but not among l/l homozygotes.

We previously showed that variations in the gene encoding the neurotransmitter-metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) moderate children’s sensitivity to maltreatment.

MAOA has high affinity for 5-HTT, raising the possibility that the protective effect of thel/lallele on psychiatric morbidity is further augmented by the presence of a genotype conferring high MAOA activity.

is there a limit to the relationship between the 5-HTT gene, life stress and depression?

we found that the moderation of life stress on depression was specific to a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene, because this effect was observed regardless of the individual’s MAOA gene status.

Until this study’s findings are replicated, speculation about clinical implications is premature. Nonetheless, although carriers of an s 5-HTTLPR allele who experienced four or more life events constituted only 10% of the birth cohort, they accounted for almost one quarter (23%) of the 133 cases of diagnosed depression.

Moreover, among cohort members suffering four or more stressful life events, 33% of individuals with an s allele became depressed, whereas only 17% of the l/l homozygotes developed depression.

Thus, the G E’s attributable risk and predictive sensitivity indicate that more knowledge about the functional properties of the 5-HTT gene may lead to better pharmacological treatments for those already de pressed.

Is the short 5-HTTLPR varient too prevalent for screening?

Although the short 5-HTTLPR variant is too prevalent for discriminatory screening (over half of the Caucasian population has an s allele)…

a microarray of genes might eventually identify those needing prophylaxis against life’s stressful events.

Evidence of a direct relation between the 5-HTTLPR and depression has been inconsistent

In this study, no direct association between the 5-HTT gene and depression was observed.

Previous experimental paradigms, including 5-HTT knockout mice, stress reared rhesus macaques, and human functional neuroimaging, have shown that the 5-HTT gene can interact with environmental conditions, although these experiments did not address depression.

Our study demonstrates that this G E interaction extends to the natural development of depression in a representative sample of humans.

what hypotheses could the report not study>

However, we could not test hypotheses about brain endophenotypes intermediate between the 5-HTT gene and depression because of the difficulty of taking CSF or functional magnetic resonance imaging measurements in an epidemiological cohort.

Much genetic research has been guided by the assumption that genes cause diseases, but the expectation that direct paths will be found from gene to disease has not proven fruitful for complex psychiatric disorders.

what does the findings regarding the G E interaction for the 5-HTT gene and the MAOA (another candidate gene) point to?

A different, evolutionary model.

This model assumes that genetic variants maintained at high prevalence in the population probably act to promote organisms’ resistance to environmental pathogens.

We extend the concept of environmental pathogens to include traumatic, stressful life experiences and propose that the effects of genes may be uncovered when such pathogens are measured (in naturalistic studies) or manipulated (in experimental studies).

To date, few linkage studies detect genes, many candidate gene studies fail consistent replication, and genes that replicate account for little variation in the phenotype.

The implications of their G E findingd

If replicated, our G E findings will have implications for improving research in psychiatric genetics.

Incomplete gene penetrance, a major source of error in linkage pedigrees, can be explained if a gene’s effects are expressed only among family members exposed to environ mental risk.

If risk exposure differs between samples, candidate genes may fail replication.

If risk exposure differs among participants within a sample, genes may account for little variation in the phenotype.

We speculate that some multifactorial disorders, instead of resulting from variations in many genes of small effect, may result from variations in fewer genes whose effects are conditional on expo sure to environmental risks

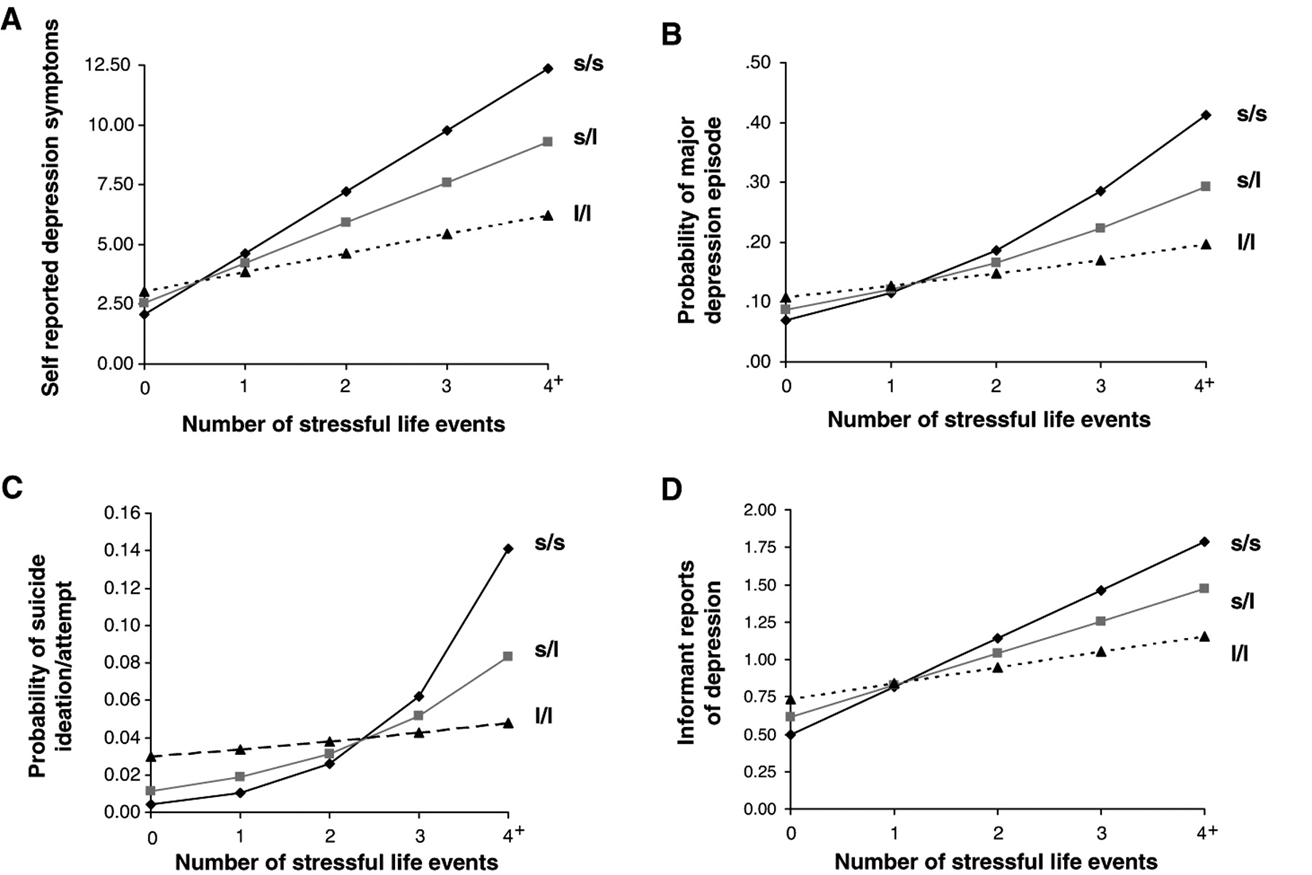

Fig 4

PPI of the right ACC. (A) All areas are shown that receive a significant context-dependent contribution from right ACC during visuospatial decisions, projected on the same rendered brain as in Fig. 1. Right ACC significantly increased its influence on posterior and anterior parts of the right IPS during visuospatial decisions. Note the specificity of this result: Even when the threshold was reduced to P 0.05, uncorrected, no other significant clusters were found throughout the brain. (B) This schema summarizes the negative findings for right ACC: As indicated by the gray dashed lines, right ACC shows no context-dependent contributions to any left-hemispheric area during visuospatial decisions and none to any left- or right-hemispheric area at all during letter decisions.

Fig 1

Results of multiple regression analyses estimating the association between number of stressful life events (between ages 21 and 26 years) and depression outcomes at age 26 as a function of 5-HTTgenotype. The main effect of 5-HTTLPR (i.e., an effect not conditional on other variables) was marginally significant, the main effect of stressful life events was significant, and the interaction between 5-HTTLPR and life events was in the predicted direction. The interaction showed that the effect of life events on self-reports of depression symptoms was stronger among individuals carrying an s allele than among l/l homozygotes.

The main effect of 5-HTTLPR was not significant, the main effect of life events was significant, and the G-E was in the predicted direction. Life events predicted a diagnosis of major depression among s carriers but not among l/l homozygotes.

Probability of suicide ideation or attempt. The main effect of 5-HTTLPR was not significant, the main effect of life events was significant, and the G-E interaction was in the predicted direction. Life events predicted suicide ideation or attempt among s carriers but not among l/l homozygotes.

Informant reports of depression. The main effect of 5-HTTL PR was not significant, the main effect of life events was significant, and the G E was in the predicted direction. The effect of life events on depression was stronger among s carriers than among l/l homozygotes

Fig 2

Results of regression analysis estimating the association between childhood maltreatment (between the ages of 3 and 11 years) and adult depression (ages 18 to 26),as a function of 5-HTTgenotype. Among the 147 s/s homozygotes,92(63%),39(27%),and16(11%) study members were in the no maltreatment, probable maltreatment, and severe maltreatment groups, respectively.Amongthe435s/l heterozygotes,286(66%),116(27%), and33 (8%) were in the no, probable, and severe maltreatment groups.

Among the265 l/l homozygotes, 172(65%), 69(26%), and 24(9%) were in the no, probable, and severe maltreatment groups. The main effect of 5-HTTLPR was not significant, the main effect of childhood maltreatment was significant, and the G-E interaction was in the predicted direction. The interaction showed that childhood stress predicted adult depression only among individuals carrying an allele and not among l/l homozygotes

Fig 3

The percentage of individuals meeting diagnostic criteria for depression at age 26, as a function of 5-HTT genotype and number of stressful life events between the ages of 21 and 26. The figure shows individuals with either one or two copies of the short allele (left) and individuals homozygous for the long allele (right). In a hierarchical logistic regression model, the main effect of genotype was not significant, the main effect of number of life events was significant and the interaction between genotype and number of life events was significant.

Knowt

Knowt