L12: Fluorescence quenching

Review

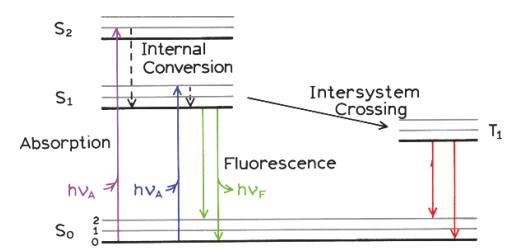

triplet state - milliseconds → seconds long time

Temperature effects

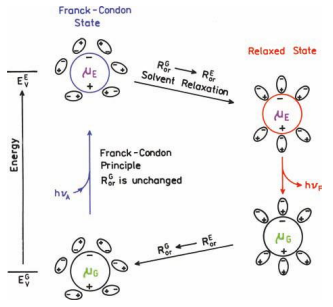

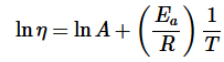

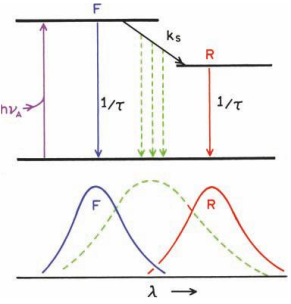

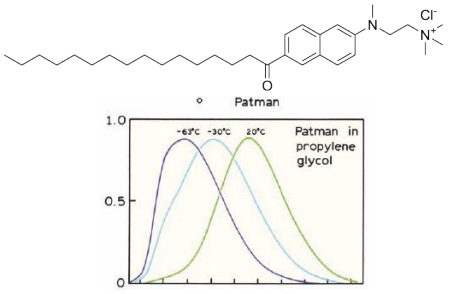

At low temperatures, the solvent can become more viscous, and the time for solvent reorientation increases

Solvent relaxation proceeds with a rate kS .

If kS <<<< fluorescence rate (γ =1/τ), then one expects to observe the emission spectrum of the unrelaxed F state.

If kS >> γ, then emission from the relaxed state will be observed.

flow - longer scale than molecular - viscous drag

Fluorescence quenching

Quenching is a special case of non-radiative decay pathway: Any process that leads to a reduction in fluorescence intensity (or QY)

Relevance in studies

molecular interaction studies

When a quencher molecule interacts with a fluorophore, it alters the emission intensity or lifetime.

This change can reveal:

Binding affinity

Conformational changes

Proximity and orientation of molecules

Used to study protein-ligand binding, DNA-protein interactions, and enzyme kinetics.

Example: Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in proteins helps map binding sites and protein folding pathways

nanoscale probing

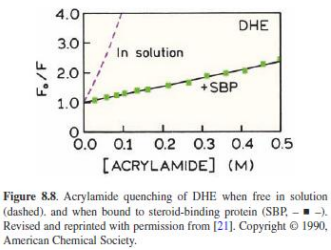

Dynamic quenching follows diffusion-based interactions, while static quenching reveals stable complex formation.

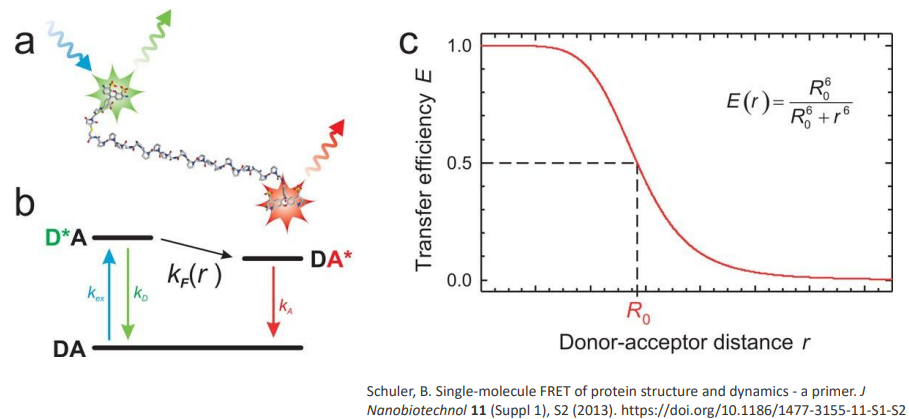

By tracking quenching efficiency, researchers can measure distances at the 1-10 nm scale.

This is the foundation for Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), widely used to measure molecular distances.

Example: FRET is used to study protein folding, RNA dynamics, and membrane fusion.

Collisional quenching - excited donor collides with the acceptor and provides energy transfer to the acceptor

acceptor has to have overlap of absorption range with emission range of donor

ideal distance - 1-5 nm

Environmental Sensing and probing

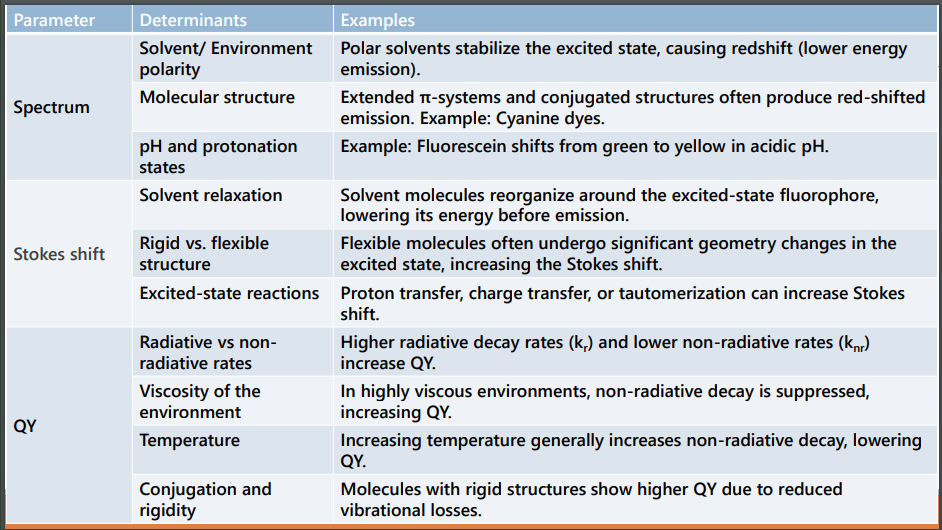

highly sensitive to the molecular environment - Changes in solvent polarity, viscosity, or the presence of metal ions

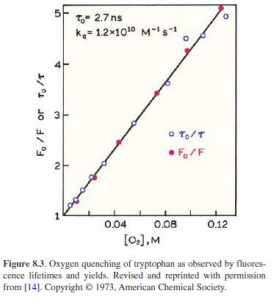

Oxygen quenching is used to measure oxygen concentration in biological tissues.

pH-sensitive probes exploit quenching behavior to monitor cellular environments

Types of quenching

1. Collisional quenching – Excited state fluorophore is deactivated by another molecule. Fluorophore returns to ground state and there is no chemical reaction in the process

2. Static quenching – Static quenching occurs when molecules create a complex in the ground state, before excitation occurs

3. Light driven mechanisms – attenuation of incident light by highly concentrated molecules (inner filter effect)Quenchers and quenching mechanisms

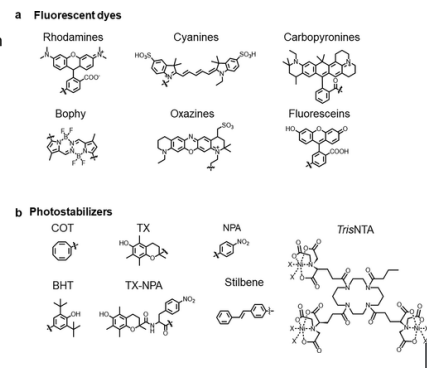

Examples of quenchers: oxygen, halogens, amines, and electron-deficient molecules like acrylamide. Quenchers promote IC

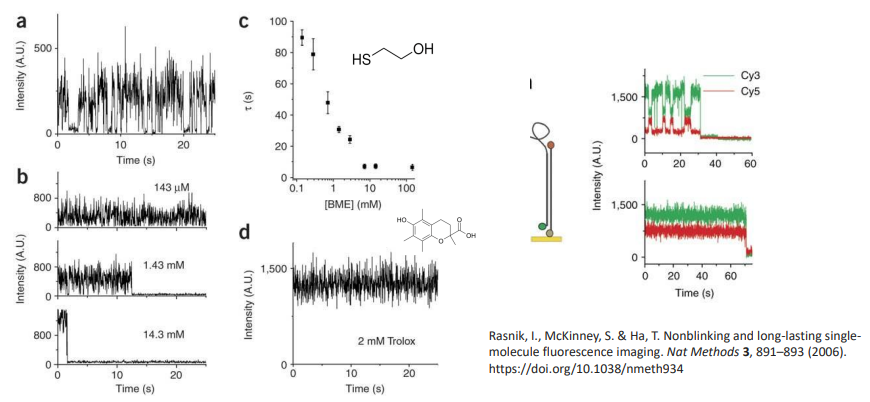

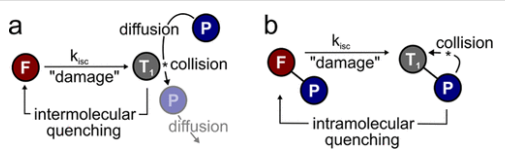

oxygen scavenging improves signal

air oxygen - triplet site

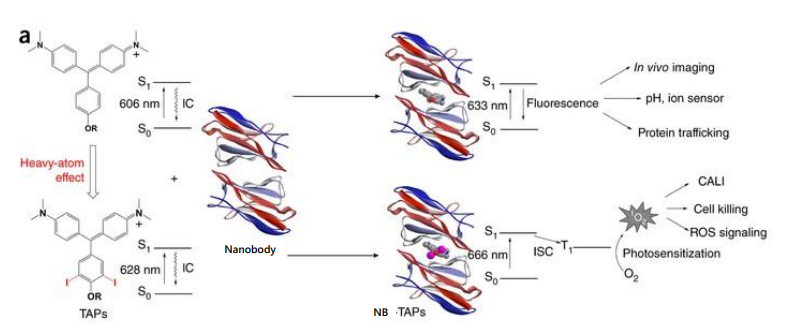

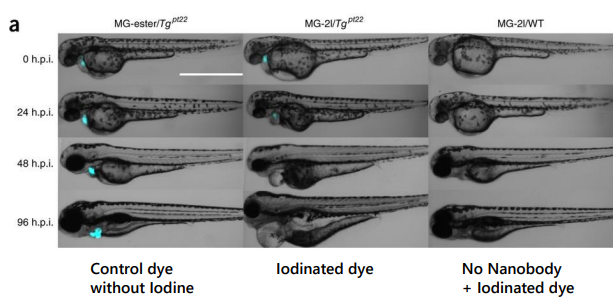

Heavy atom effect

Halogens promote IC to triplet state, promoted by spin–orbit coupling of the excited (singlet) fluorophore and the halogen

Halogenated compounds such as trichloroethanol and bromobenzene also act as collisional quenchers

collisional mass

Diffusion coefficient (D) of oxygen in water at 25C is 2.5E3 µm2/s.

During a typical fluorescence lifetime of 4 ns, an oxygen molecule can diffuse approximately 45 Å. Longer fluorescence lifetimes allow diffusion over greater distances. For instance, with lifetimes of 20 ns and 100 ns, the average diffusion distances for oxygen are approximately 100 Å and 224 Å, respectively

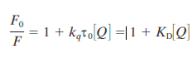

Quantitative description

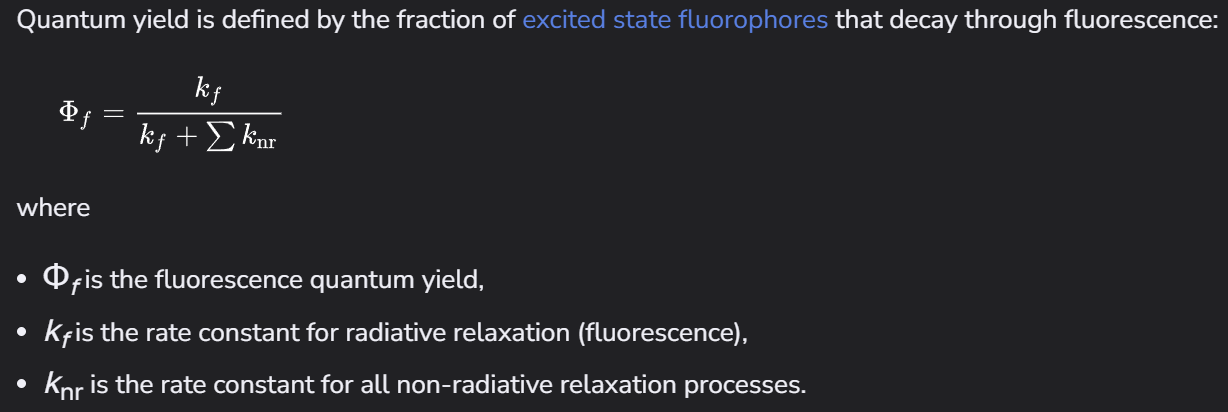

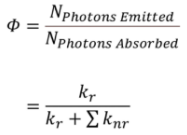

intensity, fluoresecene, quantum yield

kqtau0 = Ksv - constant unique to each quencher-fluorophore pair

Key assumptions of the Stern-Volmer framework

• The quencher interacts only with the fluorophore in the excited state (dynamic quenching).

• The quencher diffuses freely within the sample.

• There are no static (pre-formed complex) quenching interactions present.