Ch 13 Notes

What it is: The Big Mac Index is an informal economic indicator created by The Economist in 1986.

Purpose: It compares the price of a Big Mac in different countries to assess whether a currency is undervalued or overvalued relative to the U.S. dollar.

Based on: Purchasing power parity (PPP), which suggests identical goods should cost the same worldwide in the absence of trade barriers.

How it works:

If a Big Mac in a country costs more than in the U.S., that currency may be overvalued.

If it costs less, the currency may be undervalued.

Why it's useful: Provides a simple, accessible way to evaluate currency misalignments.

Limitations:

A Big Mac is a specific product, so not all economic factors (like labor or rent) are accounted for.

It’s a fun tool for casual analysis but not a perfect economic measure.

Relative Purchasing Power Parity (RPPP) is an economic theory that suggests that the exchange rate between two countries’ currencies will adjust over time to reflect changes in the relative price levels of the two countries.

In other words, it states that the percentage change in the exchange rate between two currencies over a period should be proportional to the difference in inflation rates between the two countries.

Mathematically, RPPP can be expressed as:

(E1/E0) = (1+Inflation1) / (1+Inflation0)

Where:

E1= is the exchange rate at time 1 (future exchange rate),

E0 = is the exchange rate at time 0 (current exchange rate),

Inflation1= is the inflation rate of the foreign country,

Inflation0 = is the inflation rate of the domestic country.

RPPP suggests that if one country experiences higher inflation than another, its currency will depreciate relative to the other currency to maintain the same purchasing power for consumers in both countries.

This is an important concept in international economics and is often used to forecast exchange rates based on inflation trends.

The Law of One Price

What it is: The Law of One Price is an economic theory that states that in an efficient market, identical goods should have the same price when expressed in a common currency, assuming no transportation costs, tariffs, or other trade barriers.

Core idea:

If a good is sold in two different locations, its price should be the same when adjusted for exchange rates, otherwise, an arbitrage opportunity exists.

In other words, if the price of a product differs across locations, traders would buy the cheaper product and sell it in the more expensive market until prices converge.

Conditions for it to hold:

No transaction costs (e.g., shipping, taxes, tariffs).

No government-imposed trade barriers or regulations.

Perfect market competition and information.

Examples:

If a Big Mac sells for $5 in the U.S. and €4 in the Eurozone, and the exchange rate is $1 = €0.80, then the price in the Eurozone should be equivalent to $5 in the U.S. to avoid arbitrage opportunities.

Implications:

Suggests that exchange rates and prices should adjust to eliminate arbitrage opportunities.

Used in economic models like Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) to explain long-term trends in currency values.

Limitations:

Doesn’t hold in the real world due to factors like transportation costs, tariffs, differences in product quality, and local market conditions.

Assumes perfect competition and no monopoly power, which rarely exist in practice.

To calculate the over or undervaluation of a foreign currency using PPP exchange rate and actual exchange rate, you can use the following formula:

Formula for Over or Undervaluation: Over/Undervaluation=(Actual Exchange Rate / PPP Exchange Rate) −1

Where:

Actual Exchange Rate: The current exchange rate between the two currencies (how much one unit of the foreign currency is worth in terms of the domestic currency).

PPP Exchange Rate: The exchange rate implied by purchasing power parity (PPP), based on the relative price of an identical good (like a Big Mac) in both countries.

Steps:

Determine the Actual Exchange Rate: The real-world exchange rate (e.g., how much 1 unit of foreign currency costs in terms of your domestic currency).

Calculate the PPP Exchange Rate: Based on the price of a specific good (e.g., Big Mac) in both countries, the PPP exchange rate is calculated by dividing the price of the good in the foreign currency by the price of the good in the domestic currency.

PPP Exchange Rate=Price of Good in Foreign Currency / Price of Good in Domestic Currency

Calculate Over/Undervaluation:

If the result is greater than 0, the foreign currency is undervalued (its actual exchange rate is higher than the PPP exchange rate).

If the result is less than 0, the foreign currency is overvalued (its actual exchange rate is lower than the PPP exchange rate).

Example:

Actual Exchange Rate: 1 USD = 8 CNY (Chinese Yuan).

Price of a Big Mac: 5 USD in the U.S., and 30 CNY in China.

PPP Exchange Rate:

PPP Exchange Rate=30 CNY5 USD=6 CNY/USD\text{PPP Exchange Rate} = \frac{30 \text{ CNY}}{5 \text{ USD}} = 6 \text{ CNY/USD}

Over/Undervaluation:

Over/Undervaluation=8 CNY/USD6 CNY/USD−1=0.33\text{Over/Undervaluation} = \frac{8 \text{ CNY/USD}}{6 \text{ CNY/USD}} - 1 = 0.33

This means the Chinese Yuan is undervalued by 33% relative to the U.S. dollar.

What are PPP adjustments and why do we need them? notes

GDP and Measurement Challenges

GDP measures total national output in local currency, making cross-country comparisons difficult.

Exchange rates alone do not reflect differences in price levels.

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and International Dollars

PPP adjusts for price level differences by using a hypothetical currency, 'international dollars.'

PPP conversion rates translate local currencies into international dollars for meaningful economic comparisons.

Why PPP Matters

Living standards depend on local purchasing power, not just nominal income.

A fixed amount of money can buy more in lower-cost countries than in high-cost ones.

PPP adjustments provide better comparisons of GDP, poverty rates, and living costs.

Market Exchange Rates vs. PPP Conversion Rates

Market exchange rates reflect currency trade but not local price levels.

Non-tradable goods (e.g., housing, services) impact local price levels but are not reflected in exchange rates.

Why Rich Countries Have Higher Prices (Penn Effect)

Richer countries tend to have higher wages and price levels.

The Balassa-Samuelson model explains that productivity in tradable goods drives up overall price levels.

Limitations of PPP Adjustments

Data limitations: Many low-income countries lack comprehensive price data.

Difficulty defining a standard basket of goods for accurate cross-country comparisons.

Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem

Free trade has several potential drawbacks, despite its many benefits.

Here are some common criticisms:

Job Losses in Certain Industries – Domestic industries that cannot compete with cheaper imports may decline, leading to layoffs and economic hardship in specific sectors.

Wage Suppression – Increased competition with lower-wage countries can drive down wages, particularly for low-skilled workers.

Loss of Domestic Industries – Some industries may be unable to survive without protection, leading to a loss of national production capacity and dependence on foreign suppliers.

Trade Deficits – Countries with persistent trade deficits (importing more than they export) can face economic instability or increased debt.

Environmental Concerns – Free trade can encourage production in countries with weaker environmental regulations, leading to pollution and resource depletion.

Exploitation of Workers – Companies may relocate production to countries with lax labor laws, leading to worker exploitation and poor working conditions.

Loss of Sovereignty – Trade agreements may limit a country's ability to implement policies like tariffs or subsidies to protect its industries.

Economic Disruptions – Rapid shifts in trade can lead to short-term economic disruptions, even if there are long-term benefits.

While free trade promotes economic efficiency and consumer benefits, it can also create inequalities and vulnerabilities that require careful policy management.

The Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem (H-O Theorem) is a key concept in international trade theory that explains how countries specialize in production based on their factor endowments (the resources they have in abundance).

Core Idea: A country will export goods that intensively use its abundant factors of production and import goods that intensively use its scarce factors.

Key Assumptions:

Two countries, two goods, and two factors of production (typically labor and capital).

Countries have different relative endowments of these factors.

Goods require different proportions of labor and capital to produce (some goods are labor-intensive, others are capital-intensive).

Free trade allows countries to specialize based on their comparative advantage.

Example:

The U.S. (capital-abundant) will export capital-intensive goods (like airplanes or tech products).

Bangladesh (labor-abundant) will export labor-intensive goods (like textiles or garments).

Implications:

Explains why trade happens even if countries have no absolute advantage.

Suggests that trade will benefit a country’s abundant factor (e.g., workers in a labor-rich country).

Helps understand income inequality—owners of abundant factors gain, while owners of scarce factors may lose (e.g., unskilled workers in a capital-abundant country may see lower wages).

Chapter 13.5 Fixed Exchange Rates

Fixed Exchange Rates: Strengths & Weaknesses

Overview

The U.S. has used a flexible exchange rate since abandoning the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s.

Fixed exchange rates are still used by many countries, where governments set exchange rates rather than allowing market forces to determine them.

How Fixed Exchange Rates Work

Governments set the nominal exchange rate and may adjust it periodically.

This system contrasts with flexible exchange rates, where market supply and demand determine currency values.

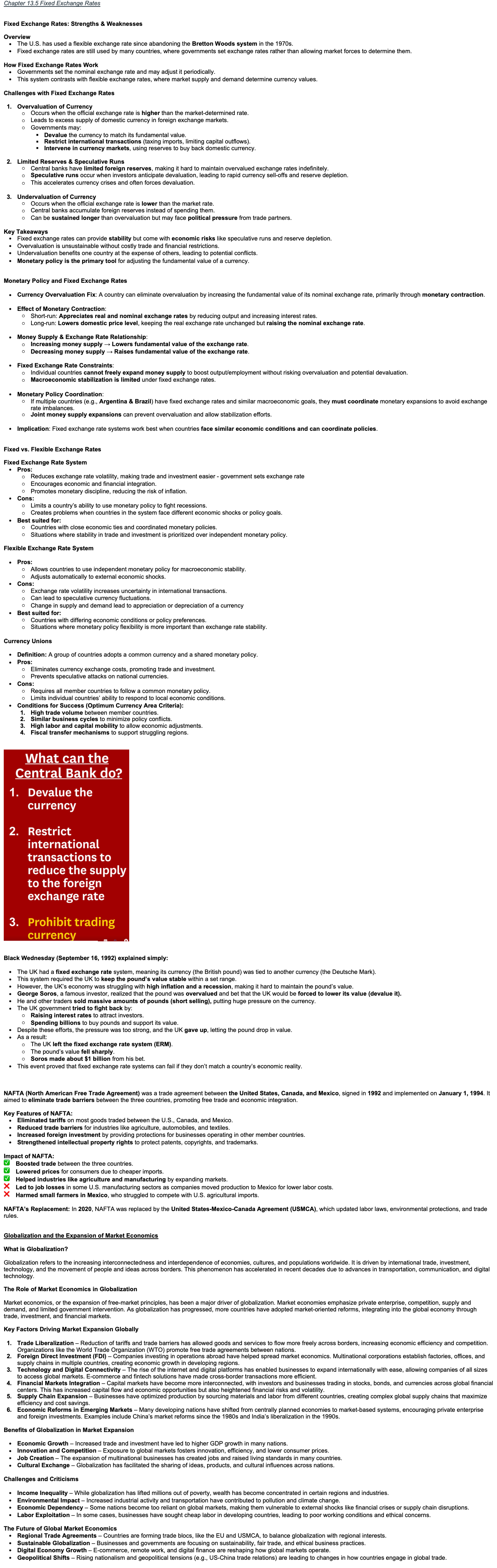

Challenges with Fixed Exchange Rates

Overvaluation of Currency

Occurs when the official exchange rate is higher than the market-determined rate.

Leads to excess supply of domestic currency in foreign exchange markets.

Governments may:

Devalue the currency to match its fundamental value.

Restrict international transactions (taxing imports, limiting capital outflows).

Intervene in currency markets, using reserves to buy back domestic currency.

Limited Reserves & Speculative Runs

Central banks have limited foreign reserves, making it hard to maintain overvalued exchange rates indefinitely.

Speculative runs occur when investors anticipate devaluation, leading to rapid currency sell-offs and reserve depletion.

This accelerates currency crises and often forces devaluation.

Undervaluation of Currency

Occurs when the official exchange rate is lower than the market rate.

Central banks accumulate foreign reserves instead of spending them.

Can be sustained longer than overvaluation but may face political pressure from trade partners.

Key Takeaways

Fixed exchange rates can provide stability but come with economic risks like speculative runs and reserve depletion.

Overvaluation is unsustainable without costly trade and financial restrictions.

Undervaluation benefits one country at the expense of others, leading to potential conflicts.

Monetary policy is the primary tool for adjusting the fundamental value of a currency.

Monetary Policy and Fixed Exchange Rates

Currency Overvaluation Fix: A country can eliminate overvaluation by increasing the fundamental value of its nominal exchange rate, primarily through monetary contraction.

Effect of Monetary Contraction:

Short-run: Appreciates real and nominal exchange rates by reducing output and increasing interest rates.

Long-run: Lowers domestic price level, keeping the real exchange rate unchanged but raising the nominal exchange rate.

Money Supply & Exchange Rate Relationship:

Increasing money supply → Lowers fundamental value of the exchange rate.

Decreasing money supply → Raises fundamental value of the exchange rate.

Fixed Exchange Rate Constraints:

Individual countries cannot freely expand money supply to boost output/employment without risking overvaluation and potential devaluation.

Macroeconomic stabilization is limited under fixed exchange rates.

Monetary Policy Coordination:

If multiple countries (e.g., Argentina & Brazil) have fixed exchange rates and similar macroeconomic goals, they must coordinate monetary expansions to avoid exchange rate imbalances.

Joint money supply expansions can prevent overvaluation and allow stabilization efforts.

Implication: Fixed exchange rate systems work best when countries face similar economic conditions and can coordinate policies.

Fixed vs. Flexible Exchange Rates

Fixed Exchange Rate System

Pros:

Reduces exchange rate volatility, making trade and investment easier - government sets exchange rate

Encourages economic and financial integration.

Promotes monetary discipline, reducing the risk of inflation.

Cons:

Limits a country’s ability to use monetary policy to fight recessions.

Creates problems when countries in the system face different economic shocks or policy goals.

Best suited for:

Countries with close economic ties and coordinated monetary policies.

Situations where stability in trade and investment is prioritized over independent monetary policy.

Flexible Exchange Rate System

Pros:

Allows countries to use independent monetary policy for macroeconomic stability.

Adjusts automatically to external economic shocks.

Cons:

Exchange rate volatility increases uncertainty in international transactions.

Can lead to speculative currency fluctuations.

Change in supply and demand lead to appreciation or depreciation of a currency

Best suited for:

Countries with differing economic conditions or policy preferences.

Situations where monetary policy flexibility is more important than exchange rate stability.

Currency Unions

Definition: A group of countries adopts a common currency and a shared monetary policy.

Pros:

Eliminates currency exchange costs, promoting trade and investment.

Prevents speculative attacks on national currencies.

Cons:

Requires all member countries to follow a common monetary policy.

Limits individual countries’ ability to respond to local economic conditions.

Conditions for Success (Optimum Currency Area Criteria):

High trade volume between member countries.

Similar business cycles to minimize policy conflicts.

High labor and capital mobility to allow economic adjustments.

Fiscal transfer mechanisms to support struggling regions.

Black Wednesday (September 16, 1992) explained simply:

The UK had a fixed exchange rate system, meaning its currency (the British pound) was tied to another currency (the Deutsche Mark).

This system required the UK to keep the pound’s value stable within a set range.

However, the UK’s economy was struggling with high inflation and a recession, making it hard to maintain the pound’s value.

George Soros, a famous investor, realized that the pound was overvalued and bet that the UK would be forced to lower its value (devalue it).

He and other traders sold massive amounts of pounds (short selling), putting huge pressure on the currency.

The UK government tried to fight back by:

Raising interest rates to attract investors.

Spending billions to buy pounds and support its value.

Despite these efforts, the pressure was too strong, and the UK gave up, letting the pound drop in value.

As a result:

The UK left the fixed exchange rate system (ERM).

The pound’s value fell sharply.

Soros made about $1 billion from his bet.

This event proved that fixed exchange rate systems can fail if they don’t match a country’s economic reality.

NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) was a trade agreement between the United States, Canada, and Mexico, signed in 1992 and implemented on January 1, 1994. It aimed to eliminate trade barriers between the three countries, promoting free trade and economic integration.

Key Features of NAFTA:

Eliminated tariffs on most goods traded between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico.

Reduced trade barriers for industries like agriculture, automobiles, and textiles.

Increased foreign investment by providing protections for businesses operating in other member countries.

Strengthened intellectual property rights to protect patents, copyrights, and trademarks.

Impact of NAFTA:

✅ Boosted trade between the three countries.

✅ Lowered prices for consumers due to cheaper imports.

✅ Helped industries like agriculture and manufacturing by expanding markets.

❌ Led to job losses in some U.S. manufacturing sectors as companies moved production to Mexico for lower labor costs.

❌ Harmed small farmers in Mexico, who struggled to compete with U.S. agricultural imports.

NAFTA’s Replacement: In 2020, NAFTA was replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which updated labor laws, environmental protections, and trade rules.

Globalization and the Expansion of Market Economics

What is Globalization?

Globalization refers to the increasing interconnectedness and interdependence of economies, cultures, and populations worldwide. It is driven by international trade, investment, technology, and the movement of people and ideas across borders. This phenomenon has accelerated in recent decades due to advances in transportation, communication, and digital technology.

The Role of Market Economics in Globalization

Market economics, or the expansion of free-market principles, has been a major driver of globalization. Market economies emphasize private enterprise, competition, supply and demand, and limited government intervention. As globalization has progressed, more countries have adopted market-oriented reforms, integrating into the global economy through trade, investment, and financial markets.

Key Factors Driving Market Expansion Globally

Trade Liberalization – Reduction of tariffs and trade barriers has allowed goods and services to flow more freely across borders, increasing economic efficiency and competition. Organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) promote free trade agreements between nations.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) – Companies investing in operations abroad have helped spread market economics. Multinational corporations establish factories, offices, and supply chains in multiple countries, creating economic growth in developing regions.

Technology and Digital Connectivity – The rise of the internet and digital platforms has enabled businesses to expand internationally with ease, allowing companies of all sizes to access global markets. E-commerce and fintech solutions have made cross-border transactions more efficient.

Financial Markets Integration – Capital markets have become more interconnected, with investors and businesses trading in stocks, bonds, and currencies across global financial centers. This has increased capital flow and economic opportunities but also heightened financial risks and volatility.

Supply Chain Expansion – Businesses have optimized production by sourcing materials and labor from different countries, creating complex global supply chains that maximize efficiency and cost savings.

Economic Reforms in Emerging Markets – Many developing nations have shifted from centrally planned economies to market-based systems, encouraging private enterprise and foreign investments. Examples include China’s market reforms since the 1980s and India’s liberalization in the 1990s.

Benefits of Globalization in Market Expansion

Economic Growth – Increased trade and investment have led to higher GDP growth in many nations.

Innovation and Competition – Exposure to global markets fosters innovation, efficiency, and lower consumer prices.

Job Creation – The expansion of multinational businesses has created jobs and raised living standards in many countries.

Cultural Exchange – Globalization has facilitated the sharing of ideas, products, and cultural influences across nations.

Challenges and Criticisms

Income Inequality – While globalization has lifted millions out of poverty, wealth has become concentrated in certain regions and industries.

Environmental Impact – Increased industrial activity and transportation have contributed to pollution and climate change.

Economic Dependency – Some nations become too reliant on global markets, making them vulnerable to external shocks like financial crises or supply chain disruptions.

Labor Exploitation – In some cases, businesses have sought cheap labor in developing countries, leading to poor working conditions and ethical concerns.

The Future of Global Market Economics

Regional Trade Agreements – Countries are forming trade blocs, like the EU and USMCA, to balance globalization with regional interests.

Sustainable Globalization – Businesses and governments are focusing on sustainability, fair trade, and ethical business practices.

Digital Economy Growth – E-commerce, remote work, and digital finance are reshaping how global markets operate.

Geopolitical Shifts – Rising nationalism and geopolitical tensions (e.g., US-China trade relations) are leading to changes in how countries engage in global trade.