Chapter 14: Renaissance in Northern Europe

Key Notes

- Time Period: 1400–1600

- Culture, beliefs, and physical settings

- Renaissance art is generally the art of Western Europe.

- Renaissance art is influenced by a number of concerns, including the art of the classical world, Christianity, a greater respect for naturalism, and formal artistic training.

- The Reformation and Counter-Reformation split European art between Protestant northerners and Catholic southerners.

- The north favored still life, genre, landscape, and portraiture above religious art.

- The south valued religious art, realism, dynamic compositions, and spectacle.

- Cultural interactions

- There are the beginnings of global commercial and artistic networks.

- Materials and Processes

- The period is dominated by an experimentation of visual elements, i.e., atmospheric perspective, a bold use of color, creative compositions, and an illusion of naturalism.

- Audience, functions, and patron

- There is a more pronounced identity of the artist in society

- The artist has more structured training opportunities.

- Theories and Interpretations

- Renaissance art is studied in chronological order.

- There is a large body of primary source material housed in libraries and public institutions.

Historical Background

- The Reformation started in 1517 when German monk and scholar Martin Luther nailed his grievances on All Saints Church in Wittenberg, Germany.

- Reformation: a division in western Christianity in which reformers broke away from the Catholic Church and formed a series of Protestant movements.

- It is considered to have started with the publication of the Ninety-five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517

- He unwittingly started one of Europe's biggest revolutions, producing a Christian divide and centuries of political strife.

- Germany, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands, the shortest-lived Christian nations, turned Protestant.

- Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Poland remained Catholic.

- An iconoclastic campaign against paintings and sculptures of holy figures, formerly hallowed, accompanied a Protestant surge of anti-Catholicism.

- Calvinists led the iconoclastic campaign against blasphemous and idolatrous pictures.

Patronage and Artistic Life

- The conflict between Protestant iconoclasm and Catholic images put artists squarely in the middle.

- Dürer and others sought to tackle the problem by painting portraits or downplaying religious ecstasies or saints.

- Protestants believed God could be contacted immediately via human intercession, therefore Jesus paintings were direct and strong when allowed.

- Catholics preferred Mary, saints, and priests to guide their ideas.

- Catholics said that Mary statues were reminders of the deity they prayed to.

- No idolatry.

- Due to Atlantic commerce, Northern European capitalism developed.

- This emphasized purchasing and selling art as commodities.

Northern Renaissance Painting

- Johann Gutenberg invented a moveable type printing press, one of the most significant innovations in history.

- This gadget could mass-produce books and distribute them widely.

- For the super-rich patrons of the Golden Haggadah, machine produced volumes appeared cheap and unnatural.

- Calligraphers painted the beginning letters before each chapter of Gutenberg's Bible, which was printed mechanically.

- Prints, initially woodcuts, then engravings, and finally etchings, were created by a similar mechanical technique.

- Since the artist built a prototype and reproduced it numerous times, prints were cheap.

- Although each print was cheaper than a painting, the artist profited by the amount of copies.

- Prints were ubiquitous, unlike paintings, thus they spread renown faster.

- Engraving: a printmaking process in which a tool called a burin is used to carve into a metal plate, causing impressions to be made in the surface.

- Ink is passed into the crevices of the plate and paper is applied.

- The result is a print with remarkable details and finely shaded contours

- Etching: a printmaking process in which a metal plate is covered with a ground made of wax.

- The artist uses a tool to cut into the wax to leave the plate exposed.

- The plate is then submerged into an acid bath, which eats away at the exposed portions of the plate.

- The plate is removed from the acid, cleaned, and ink is filled into the crevices caused by the acid.

- Paper is applied and an impression is made.

- Etching produces the finest detail of the three types of early prints

- Woodcut: a printmaking process by which a wooden tablet is carved into with a tool, leaving the design raised and the background cut away.

- Ink is rolled onto the raised portions, and an impression is made when paper is applied to the surface.

- Woodcuts have strong angular surfaces with sharply delineated lines

- Oil paint was the fifteenth century's second major innovation.

- Before this, wall paintings were fresco and panel paintings tempera.

- Oil paint's rich colors precisely mimic natural colors and tones.

- It produces crisp features and enamel-like surfaces.

- It retains its brilliance in rainy weather.

- Oil paint takes longer to cure than tempera and fresco, enabling painters to make modifications.

- Oil paint has been the medium of choice for most painters since its discovery in Flanders in the Early Renaissance.

- Northern European altarpieces are closets with folding wings.

- Altarpiece: a painted or sculpted panel set on an altar of a church

- The focal scene, sometimes carved rather than painted, is very essential.

- The 1425–1428 Annunciation Triptych was portable.

- Larger pieces were designed to be encased in a Gothic frame.

- The painting's frame sometimes reflected the building's architecture.

- Altarpieces generally feature a weekday-visible scene.

- Sunday services reveal the altarpiece's interior.

- Holidays may have had a third perspective for magnificent altarpieces.

- International Gothic Painting, a courtly exquisite painting style started by Italian painters like Simone Martini in the fourteenth century, impacted Northern European artists.

- Late Gothic sculpture and art include slim, elegant forms with an S-shaped curvature.

- Carefully represented elements of reality have natural details.

- Latest styles and textiles are well reflected in costumes.

- Gold indicates the figures' and patrons' affluence.

- Architecture is meticulously portrayed, sometimes with building walls exposed to show the inside.

- International Gothic paintings frequently feature lavish frames.

- Northern European painters like the Annunciation Triptych opened up wall openings to gaze inside homes.

- Instead of being proportionate, figures are usually imprisoned in their apartments.

- Tables, ground lines, and most flat surfaces slant up substantially.

- Expect high vistas.

- Symbolism is present in almost all art, although it is especially prevalent in Northern European artwork.

- Items that seem natural might be part of a symbolic network of interpretations on several levels.

- Scholars have spent much ink deciphering key writings.

- Italian Renaissance concepts were assimilated into Northern European art in the sixteenth century.

- Even though Michelangelo never visited Northern Europe, one of his creations did.

- Many Italian painters traveled, including Leonardo da Vinci.

- Northern European painting had a love of nature unlike Italian art, whether depicting Alpine landscapes, rabbits, or even clumps of soil.

- No matter how clean, landscapes usually reflect human participation, such as houses, farms, or little individuals in a large area. .

- Northern painters used high horizon lines to cover significant areas of the work with earthbound features.

- Landscapes employ atmospheric perspective, while paintings seldom use linear perspective.

- Polyptych: a many-paneled altarpiece

- Predella: The base of an altarpiece that is filled with small paintings, often narrative scenes

➼ Annunciation Triptych

Details

- Robert Campin workshop

- also called Merode Altarpiece

- 1427–1432

- An oil on wood

- Found in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

- Annunciation: in Christianity, an episode in the Book of Luke 1:26–38 in which Angel Gabriel announces to Mary that she would be the Virgin Mother of Jesus

- Triptych: a three-paneled painting or sculpture

- Triptych, or three-paneled altarpiece.

- Meticulous handling of paint; intricate details are rendered through the use of oil paint.

- Steep rising of the ground line; figures too large for the architectural space they occupy.

Function: Meant to be in a private home for personal devotion.

Technique

- Oil paint gives the surface a luminosity and shine.

- Oil allows for layers of glazes that render soft shadows.

- Oil can also be erased with turpentine, allowing for changes and corrections.

Content

- Left panel: donors, middle-class people kneeling before the holy scene.

- Messenger appears at the gate to an enclosed garden.

- Center panel: Annunciation taking place in an everyday Flemish interior.

- Symbolism

- Towels and water represent Mary’s purity; water is a baptism symbol.

- Flowers have three buds, symbolizing the Trinity; the unopened bud represents the unborn Jesus.

- Mary is seated on a kneeler near the floor, symbolizing her humility.

- Mary blocks the fireplace, the entrance to hell.

- The candlestick symbolizes Mary holding Christ in the womb.

- The Holy Spirit with a cross comes in through the window, symbolizing the divine birth.

- Humanization of traditional themes: no halos, domestic interiors, view into a Flemish cityscape.

- Right panel: Joseph is working in his carpentry workshop; the mousetraps on the windowsill and the workbench symbolize the capturing of the devil.

- The mousetraps on the bench and in the shop window opening onto the street are thought to allude to references in the writings of Saint Augustine identifying the cross as the devil’s mousetrap.

Context

- Unusually, the main panel was not commissioned.

- Wings were commissioned when the main panel was purchased; the donor portrait was added at this time.

- Donor: a patron of a work of art, who is often seen in that work

- After the donor’s marriage in the 1430s, the wife and messenger were added, which accounts for the rather squeezed-in look of the donor’s wife.

Image

➼ Arnolfini Portrait

Details

- Painted by Jan van Eyck.

- 1434

- An oil on wood

- Found in National Gallery, London

Form

- Meticulous handling of oil paint; great concentration of minute details.

- Linear perspective, but upturned ground plane and two horizon lines unlike contemporary Italian Renaissance art.

- Great care is taken in rendering elements of a contemporary Flemish bedroom.

Theories

- Traditionally assumed to be the wedding portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife.

- It may be a memorial to a dead wife, who could have died in childbirth.

- It may represent a betrothal.

- Arnolfini may be conferring legal and business privileges on his wife during an absence.

- The painting may have been meant as a gift for the Arnolfini family in Italy.

- It had the purpose of showing the prosperity and wealth of the couple depicted.

Context

- Symbolism of weddings:

- The custom of burning a candle on the first night of a wedding.

- Shoes are cast off, indicating that the couple is standing on holy ground.

- The groom is in a promising pose.

- The dog symbolizes fidelity.

- Two witnesses in the convex mirror; perhaps the artist himself, since the inscription reads “Jan van Eyck was here 1434.”

- The woman pulls up her dress to symbolize childbirth, although most likely she is not pregnant; the gesture may simply be a fashion of the time.

- Statue of Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth, appears on the bedpost.

- The man is standing near the window, symbolizing his role as someone who makes his way in the outside world; the woman appears further in the room to emphasize her role as a homemaker.

- Wealth is displayed in the opulent furnishings, the elaborate clothing, and the importing of fresh oranges from southern Europe.

Image

➼ Adam and Eve

Details

- Engraved by Albrecht Dürer

- An engraving

- Found in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Form

- Influenced by classical sculpture; Adam looks like the Apollo Belvedere, and Eve looks like Medici Venus.

- Italian massing of forms, which he learned from his Italian trips.

- Ideal image of humans before the Fall of Man (Genesis 3).

- Contrapposto of figures from the Italian Renaissance, in turn also based on classical Greek art.

- Northern European devotion to detail.

Content

- Four humors are represented in the animals:

- cat (choleric, or angry),

- rabbit (sanguine, or energetic),

- elk (melancholic, or sad),

- ox (phlegmatic, or lethargic);

- The four humors were kept in balance before the Fall of Man;

- The humors fell out of balance after the successful temptation of the serpent.

- The mouse represents Satan.

- The parrot is a symbol of cleverness.

- Adam tries to dissuade Eve; he grasps the mountain ash, a tree from which snakes recoil.

Context: Prominent placement of the artist’s signature indicates the rising status of his occupation.

Image

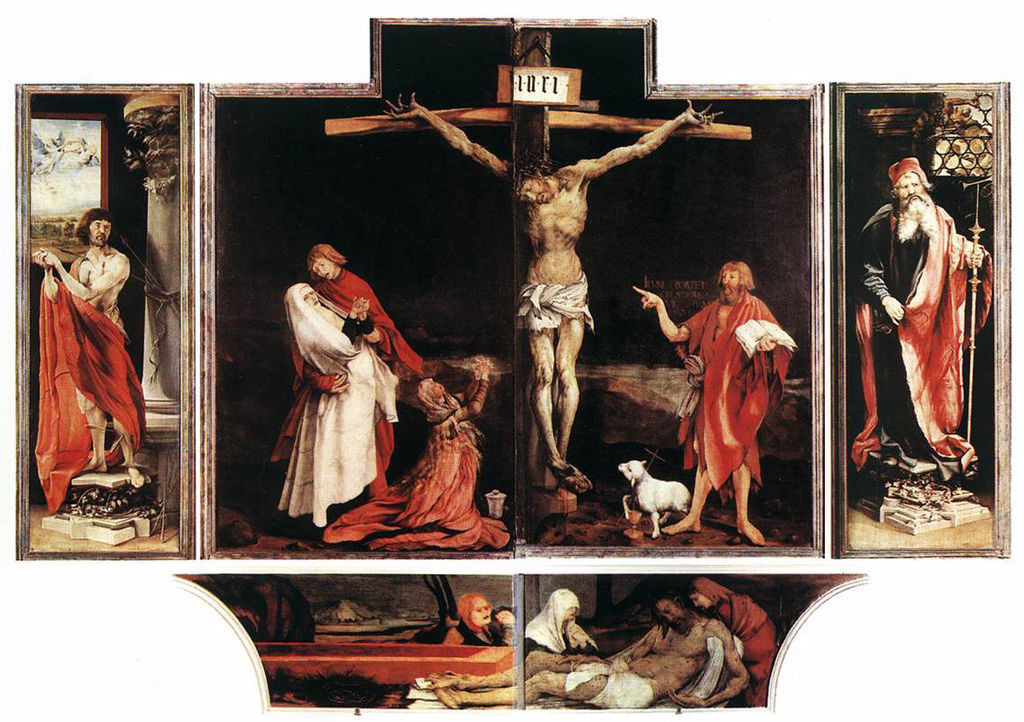

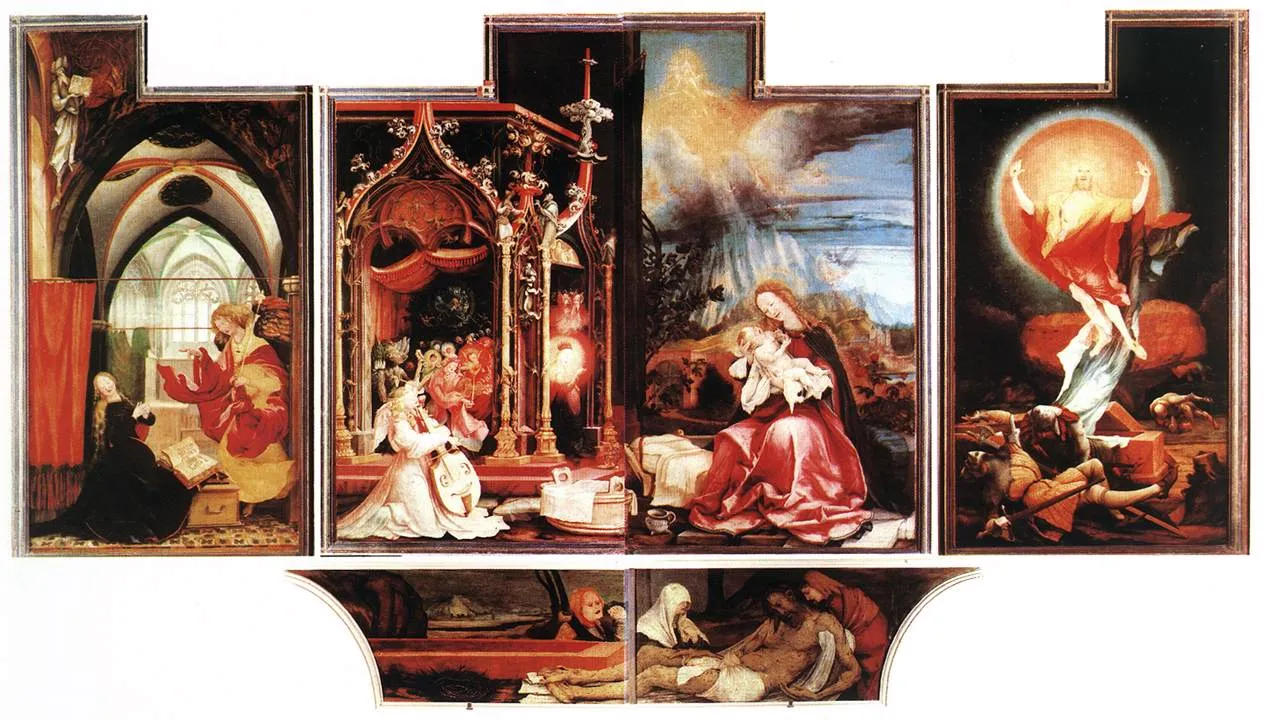

➼ Isenheim Altarpiece

Details

- Painted by Matthias Grünewald

- 1512–1516

- An oil on wood

- Found in Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar

Context

- Placed in a monastery hospital where people were treated for Saint Anthony’s fire, or ergotism—a disease caused by ingesting a fungus that grows on rye flour.

- The name of the disease explains the presence of Saint Anthony in the first view and in the third.

- Theme: healing through salvation and faith;

- Saint Sebastian (left) was saved after being shot by arrows;

- Saint Anthony (right) survived torments by devils and demons.

- Those suffering in the hospital were brought before this image, which symbolized heroism, sacrifice, and martyrdom.

- Ergotism causes convulsions and gangrene.

First view

- A scene of the crucifixion is in the center:

- Surrounded by a symbolically dark background.

- Christ’s body is dead with decomposing flesh emphasized as inspired by the writings by the mystic Saint Bridget.

- Christ’s arms are almost torn from their sockets.

- The body is lashed and whipped.

- The agony of the body is unflinchingly shown and acts as a symbol for the agony of ergotism.

- A lamb holds a cross, a common symbol for Christ, who is called the Lamb of God.

- A chalice catching the lamb’s blood parallels the chalice used to hold wine—the blood of Christ—during the Mass.

- The crucified body of Christ would have paralleled the raising of the sacramental bread called the Eucharist.

- A swooning Mary is dressed like the nuns who worked in the hospital.

- When panels open to reveal the next scene, Christ is amputated.

- Patients suffering from ergotism often endured amputation.

- Amputation also in the predella: Christ’s legs seem amputated below the kneecap.

Second view

- Marian symbols: the enclosed garden, closed gate, rosebush, rosary.

- Christ rises from the dead, on the right; his rags changed to glorious robes; he shows his wounds, which do not harm him now.

- Message to patients: earthly diseases and trials will vanish in the next world.

Third view

- Saint Anthony in the right panel has oozing boils, a withered arm, and a distended stomach: symbols of ergotism

Image

➼ Allegory of Law and Grace

Details

- Made by Lucas Cranach the Elder

- c. 1530,

- A woodcut and letterpress

Function

- Designed using the woodcut technique to make the image available to the masses.

- Its purpose was to contrast the benefits of Protestantism versus the perceived disadvantages of Catholicism.

- Influential image of the Protestant Reformation; text appears in the people’s language: German, and not the church language: Latin.

Context

- Protestantism: the faithful achieve salvation by God’s grace; guidance can be achieved using the Bible.

- Meant to reflect the Lutheran ideas about salvation.

- Done in consultation with Martin Luther, a leader in the Protestant movement.

- Left: Last Judgment

- Moses holds the Ten Commandments.

- The Ten Commandments represent the Old Law, Catholicism.

- The Law of Moses is not enough; it is not enough to live a good life.

- A skeleton chases a man into hell.

- Right: Figure bathed in Christ’s blood

- Faith in Christ alone is needed for salvation.

- Symbolically, the barren branches of the tree on the left side contrast with the full bloom on the right.

Image

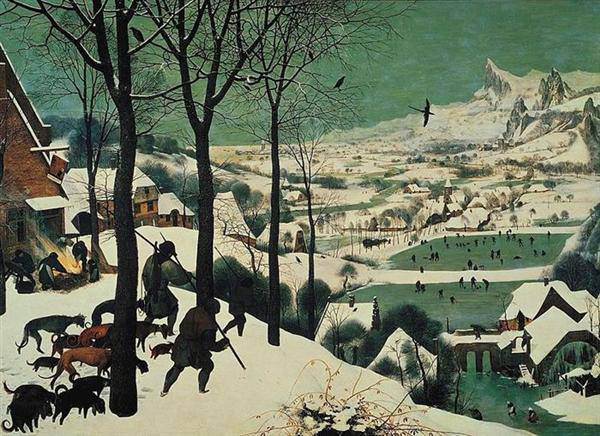

➼ Hunters in the Snow

- Details

- Painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

- 1565

- An oil on wood

- Found in Art History Museum, Vienna

- Form

- Alpine landscape; typical winter scene inspired by the artist’s trips across the Alps to Italy.

- Strong diagonals lead the eye deeper into the painting.

- Figures are peasant types, not individuals.

- Landscape has high horizon line with panoramic views, a Northern European tradition.

- Extremely detailed.

- Function

- ne of a series of six paintings representing the labors of the months—this winter scene is November/December.

- Placed in a wealthy Antwerp merchant’s home.

- Patrons were wealthy individuals of high status; Bruegel’s paintings offered them a view of the world of the peasants.

- Context

- Hunters have had little success in the winter hunt; dogs are skinny and hang their heads.

- Peasants in the sixteenth century were regarded as buffoons or figures of fun;

- Bruegel does not give them individuality but does treat them with respect

Image