ECON 2105 Final

Economics Lecture 1, Unit 1 January 8 Notes:

- There are several differing definitions for economics, scarcity being the heart of all these definitions.

- Examples: “Economics is the study of how society a manages its scarce resources.” Greg Mankiw and “Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a

relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Lionel Robbins

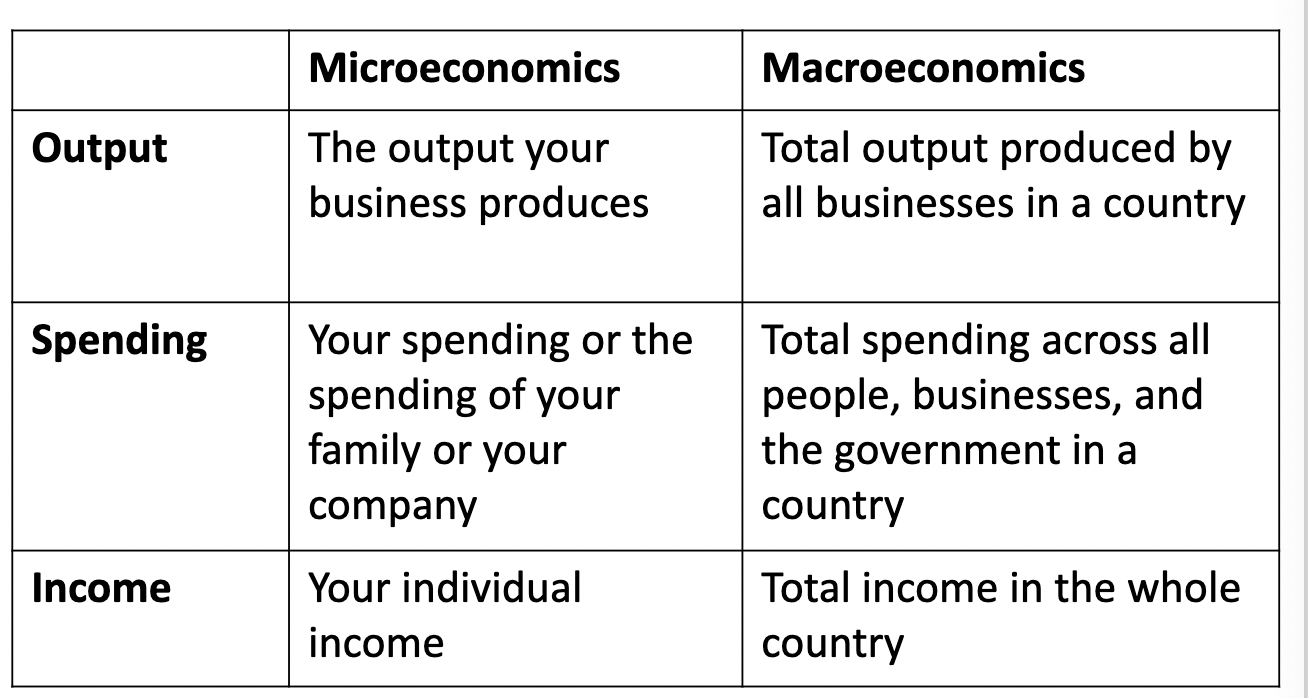

- Microeconomics is the study of choices that individuals and businesses make, the way those choices interact in markets, and the influence of specific government policies.

- Macroeconomics is the study of performance of whole national or global economies.

Chapter 1: Ten Big Ideas Notes-

- Incentives Matter

- Incentives-rewards and penalties that motivate behavior.

- Ex. Journey to private contractors that would take convicts to Australia. There were mistakes in this planning because it paid for convicts getting to Australia but not off in Australia, so the convicts did not have as much food and medicine as they needed.

- People respond to all kinds of incentives in predictable ways

- Subsidies vs taxes: Putting subsidies on cars, or taxes on things which lead to people buying less of it.

- Incentives do not just have to be monetary. People are not only interested in money but pride, and being likeable.

- Incentives need not be monetary.

- Fame, power, reputation, etc are all important incentives.

- Good Institutions Align Self-Interest with the Social Interest

- When markets work well, individuals pursuing their own interest also promote the social interest as if led by an “invisible hand”

- When markets do not work well, government can change incentives with taxes, subsidies, or regulation.

- Trade-Offs are Everywhere

- Trade-offs involved for drug testing

- In our world of scarcity, all choices come with opportunity costs.

- A resource is scarce when there isnt enough to satisfy all of our wants

- The opportunity cost of a choice is the value of the opportunities lost, namely the value of the next best alternative you must give up when making a choice.

- Every choice involves something gained and something lost.

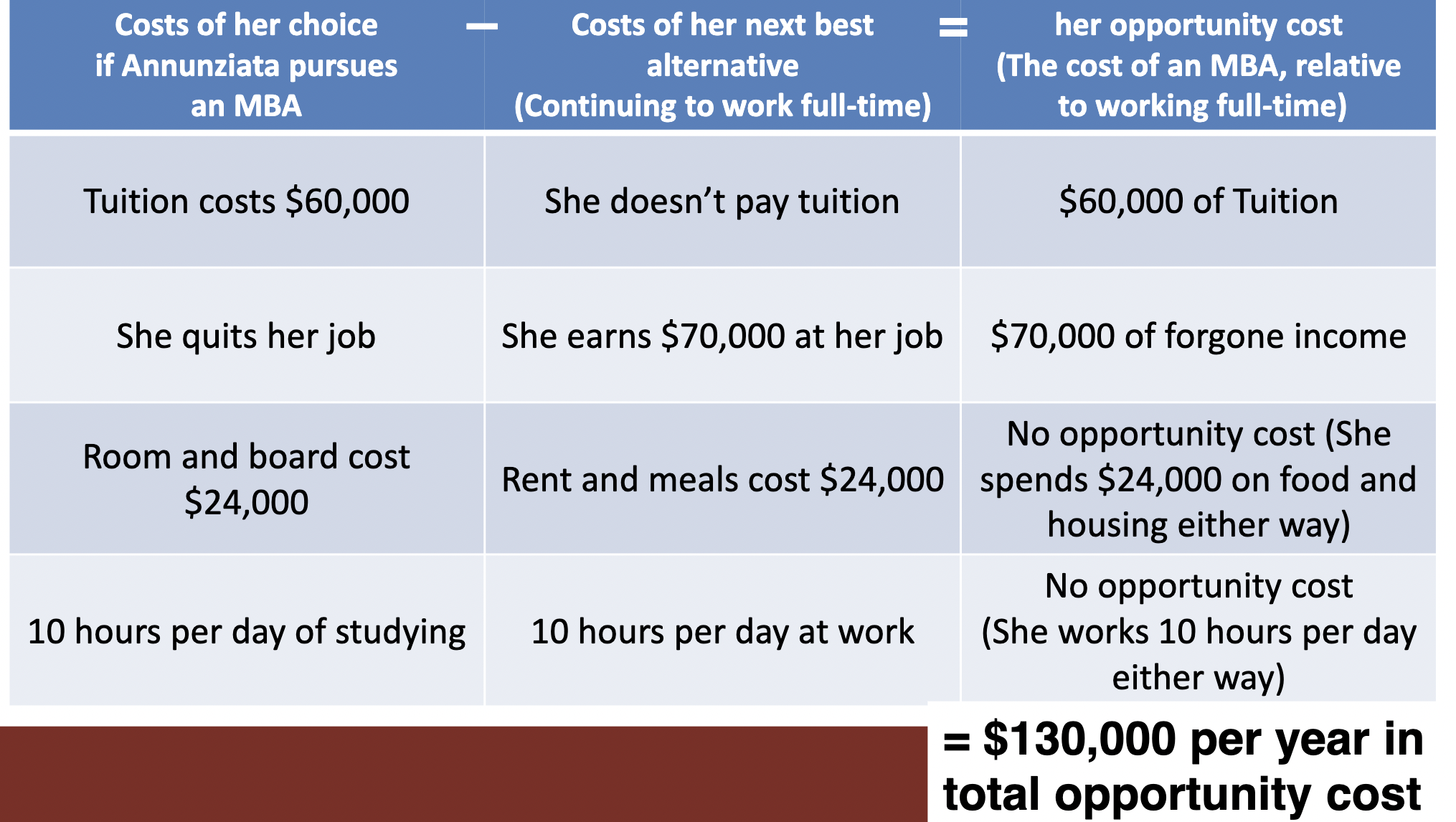

- How would we quantify the opportunity cost of Annunziata pursuing a two-year MBA full time?

- She pays $60,000 in tuition, pays for room and board, spends time studying, and quits her current job (loses that income)

Compared to what happens if she pursues her next best alternative:

- She earns $70,000 per year, still has to pay rent, and meals, and spends her time working.

Four Important Lessons About Opportunity Costs:

- Some out-of-pocket costs are opportunity costs, such as the cost of MBA tuition and fees.

- Opportunity costs don’t need to involve out-of-pocket financial costs.

- Not all out-of-pocket costs are real opportunity costs.

- Some nonfinancial costs are not opportunity costs.

When ignoring opportunity costs, you should ignore sunk costs.

- A sunk cost is a cost that has been incurred and cannot be reversed.

- A sunk cost exists whether you make your choice or not, so it is not an opportunity cost.

- When weighing costs and benefits, a good decision maker ignores sunk costs.

4. Think on the Margin

- We make choices by comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits.

- Marginal means one unit more or fewer, so a marginal cost is the cost of consuming one more unit of a good and the marginal benefit is the benefit from consuming that unit.

- Rational people will only pursue choices where the marginal benefit is greater than or equal to the marginal cost.

Applying the Cost-Benefit Principle-an example:

- How do we compare intangible benefits to monetary costs?

- Economists’ strategy: Convert each cost and each benefit into its monetary equivalent.

- What is your willingness to pay?

- That is, what is the most you would be willing to pay to obtain a particular benefit or avoid a particular cost?

- Ex. Are you willing to pay $7 for a coffee? How about $5? Or $3 or $1?

- The amount you are willing to pay depends on how much you like coffee, not the price.

- Suppose you are a bit tired and willing to pay up to $4 for a coffee

- Cost-benefit principle:

- The cost of the coffee=$3

- The benefit of the coffee=$4

- The benefit is greater than the cost.

After getting that coffee, you wouldn’t likely benefit from a second coffee as much as the first coffee. The marginal benefit of a second cup would thus be lower than the marginal cost, so you wouldn’t buy it.

- Barring violent compulsion, people wouldn’t participate in an exchange unless its marginal benefit to them exceeded its marginal costs.

- But the benefits of trade go beyond the benefits from exchange.

- Trade leads to increased production through specialization

- It also allows us to take advantage of economies of scale.

Theory of Comparitive Advantage:

- When people or nations specialize in goods in which they have a low opportunity cost, they can trade to mutual advantage

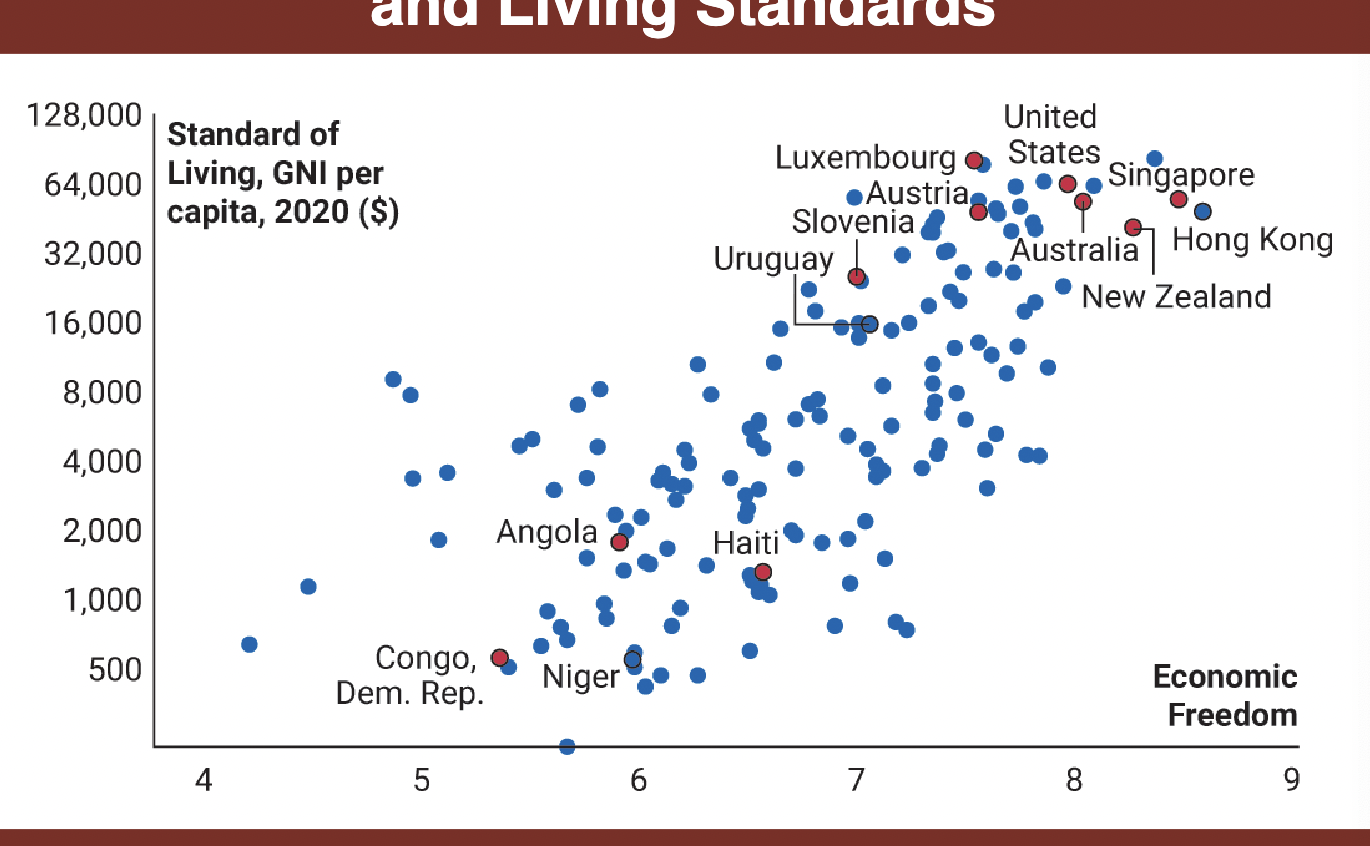

6. Wealth and Economic Growthh Are Important

- Economic growth creates wealth.

- Wealthier economies enable richer and healthier lives.

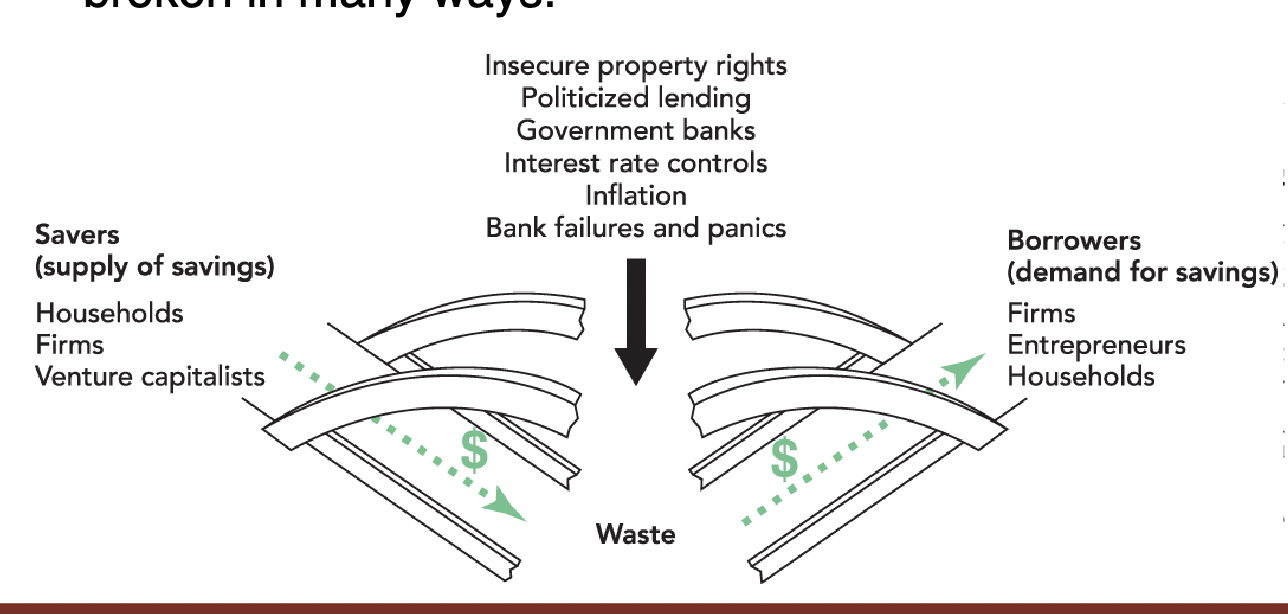

7. Institutions Matter

- Remember Principle 2: “Good Institutions Align Self-Interest with the Social Interest”

- On a broader scale, good institutions also provide incentives to save and invest in:

- Physical capital

- Human capital

- Innovation

- Efficient organization

- The right institutions foster growth:

- Property rights

- Political stability

- Honest government

- Dependable legal system

- Competitive and open markets

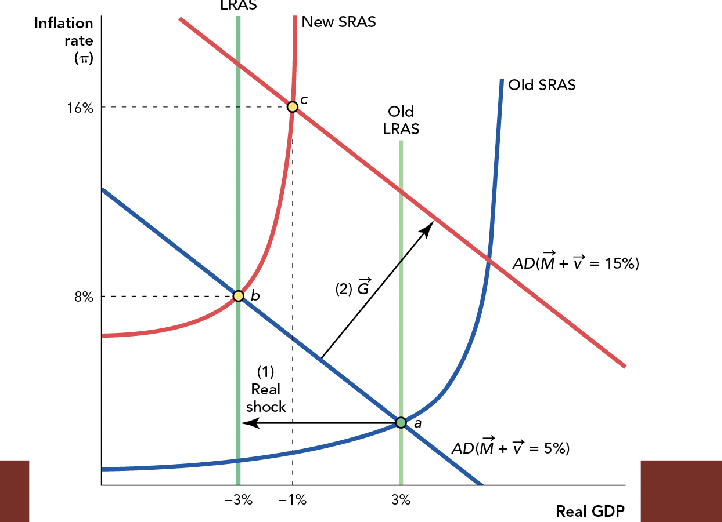

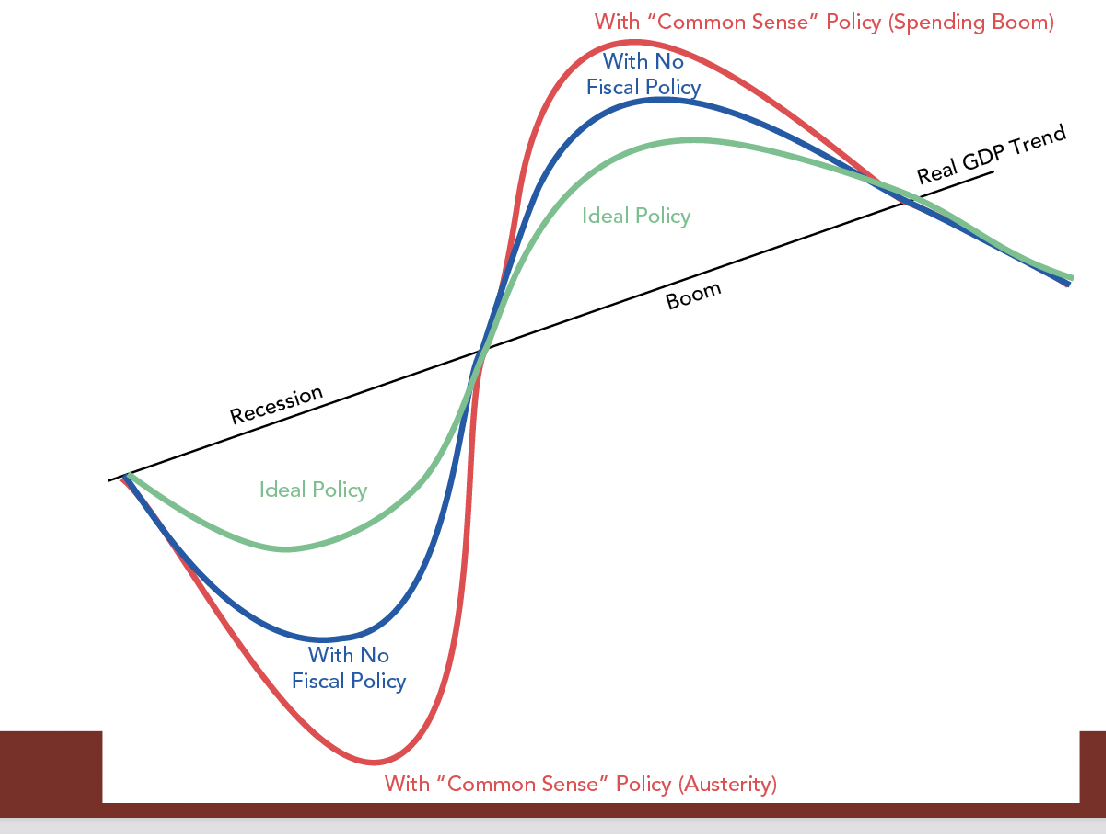

8. Booms and Busts Cannot be Avoided But Can be Moderated

- Economies do not grow at a constant pace.

- Booms and busts are a normal response to changing economic conditions

- In a downturn, output (GDP) drops and unemployment increases.

- The government can use fiscal and monetary policy to reduce the swings in output and unemployment.

- If used improperly, these tools can make the economy more volatile.

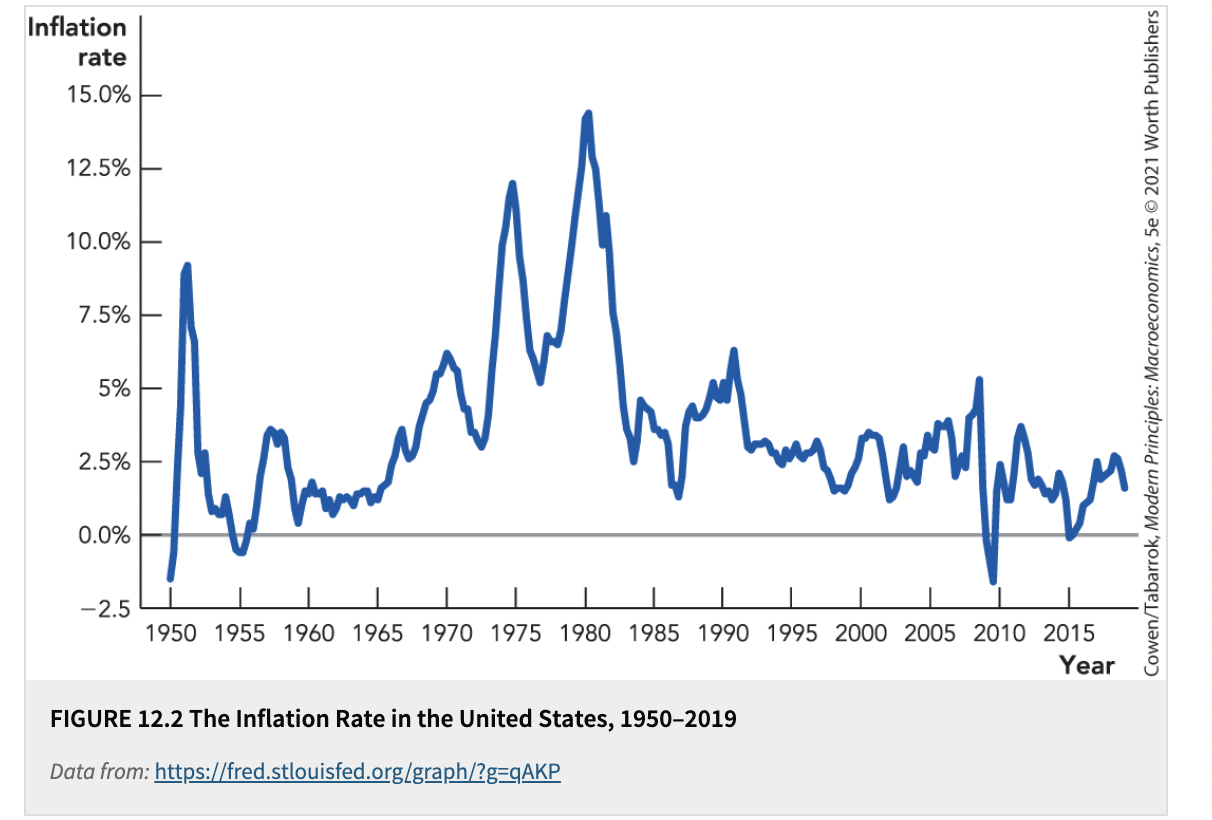

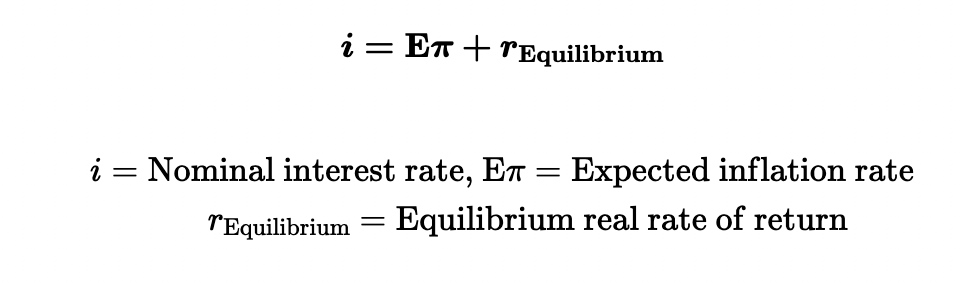

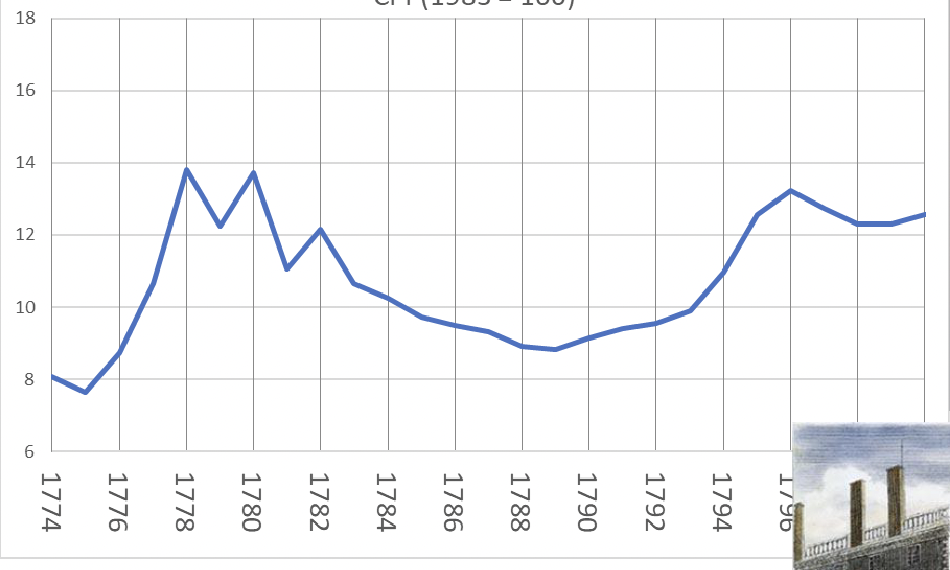

9. Inflation is Caused by Increases in the Supply of Money

- Inflation-An increase in the general level of prices.

- A country’s central bank regulates the supply of money.

- A sustained increased in the supply of money, without an increase in the supply of goods, causes prices to rise.

- Inflation can make people poorer.

- Unpredictable inflation makes it harder for people to figure out the real values of goods, services, and investments.

- Excessive inflation can lead to economic disruption.

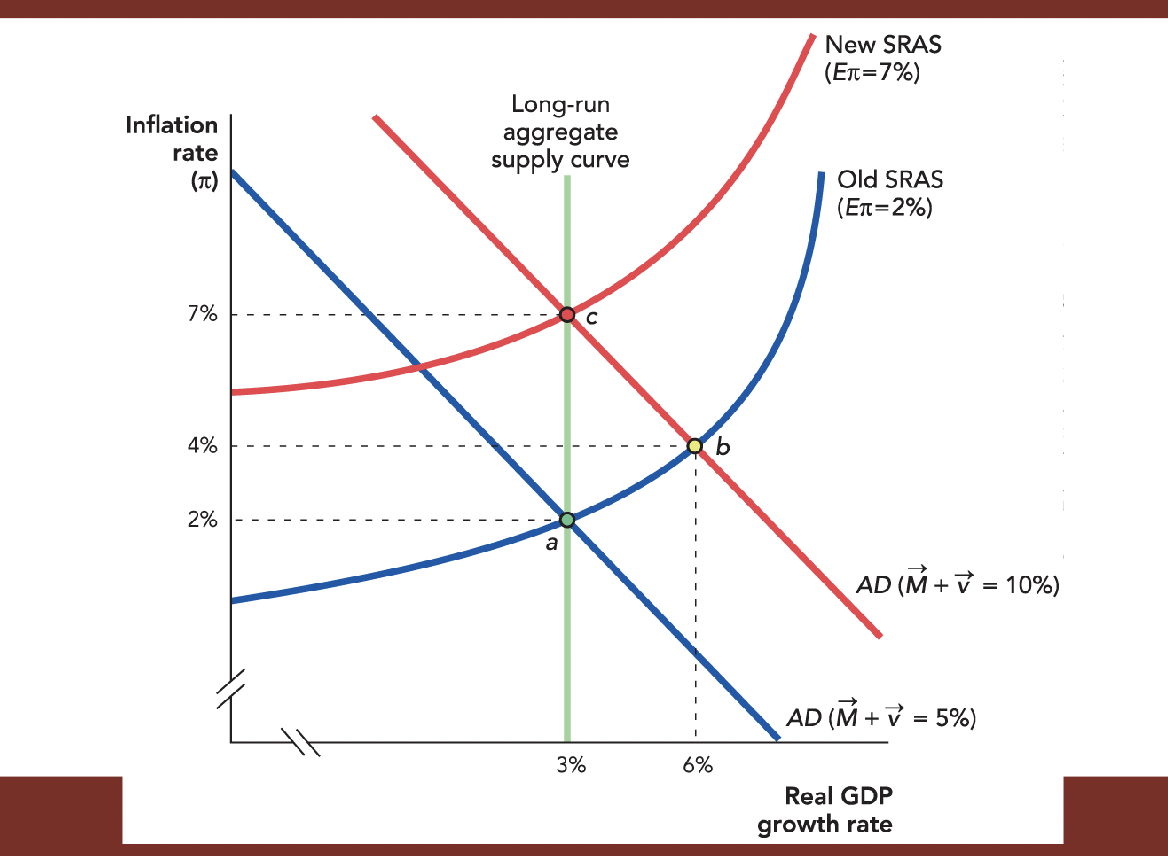

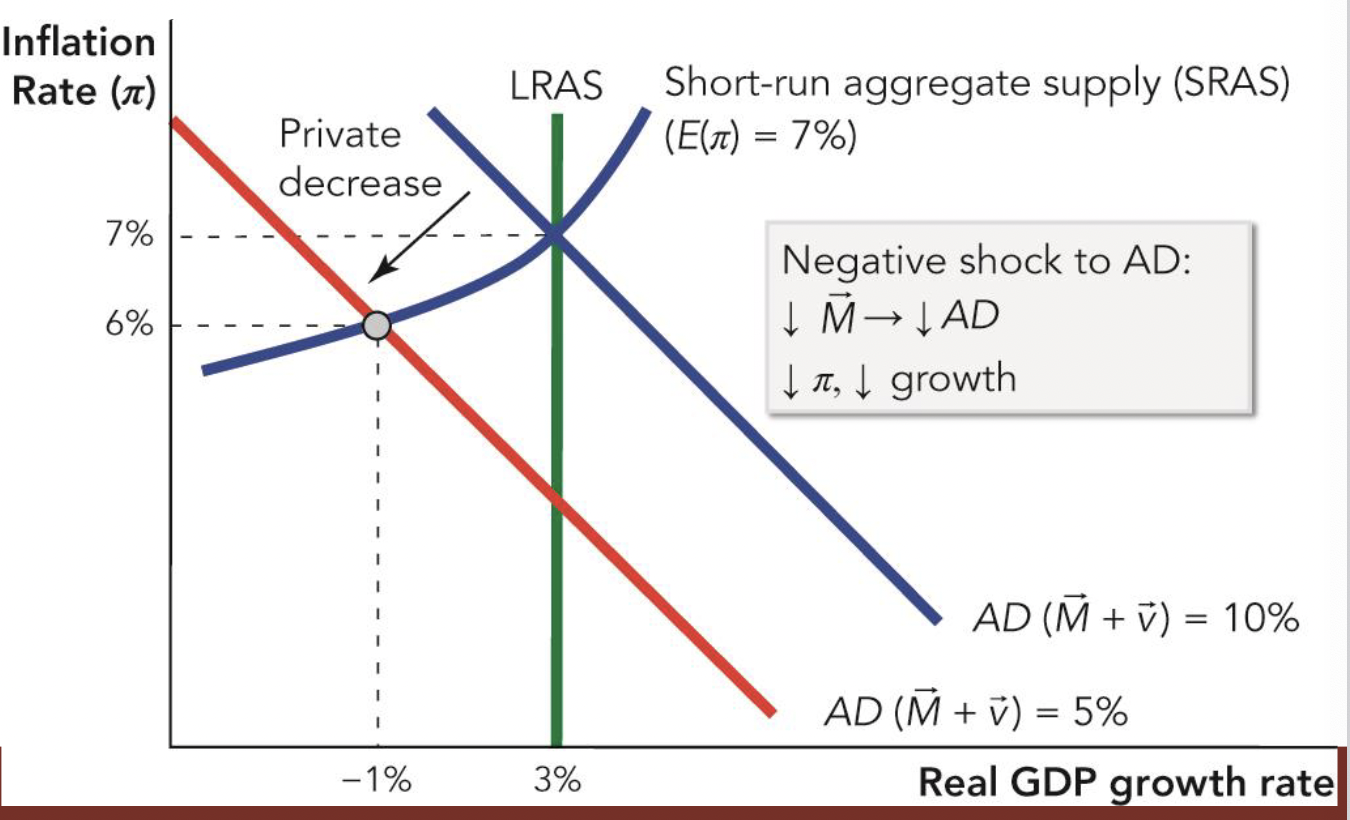

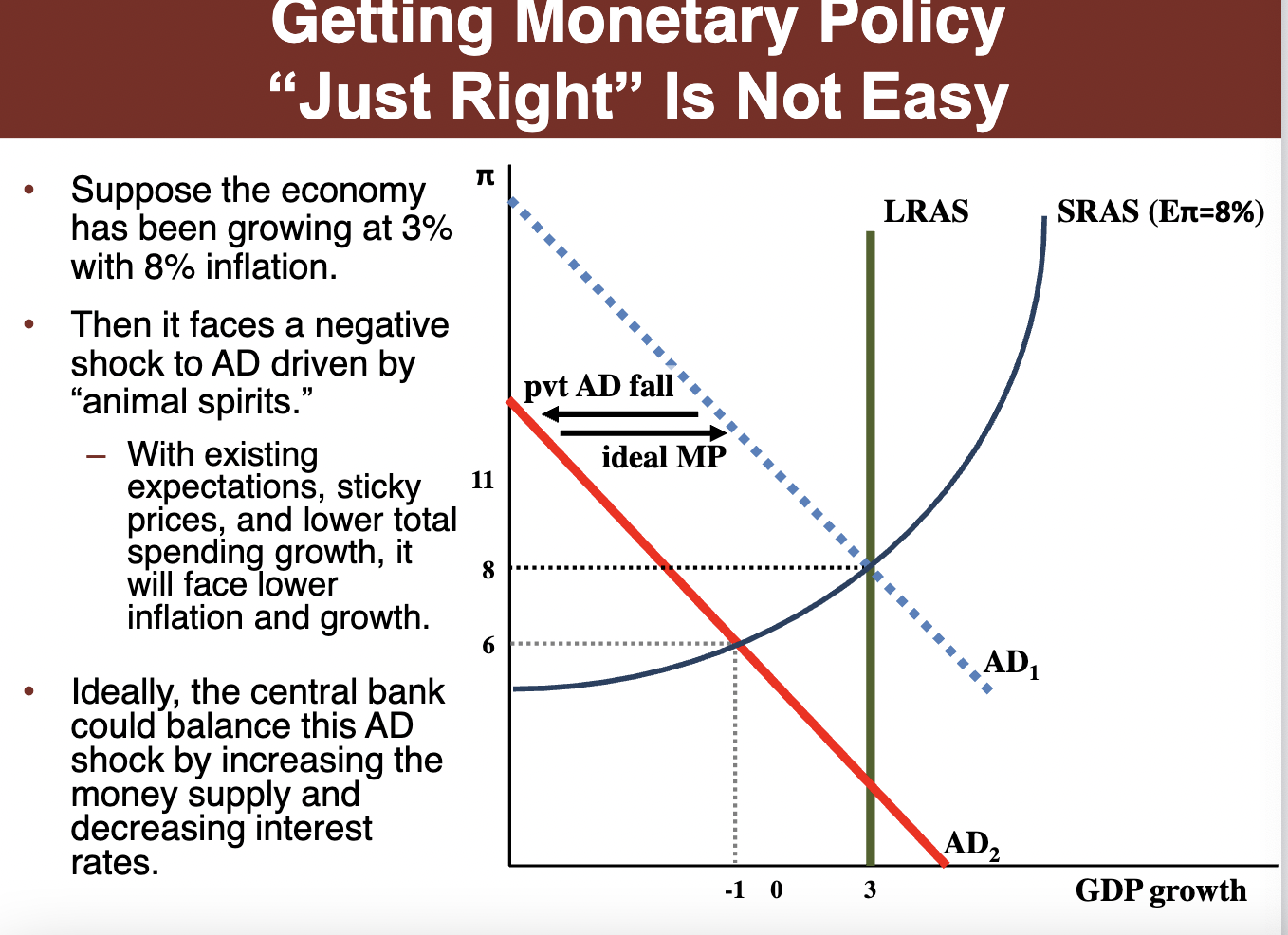

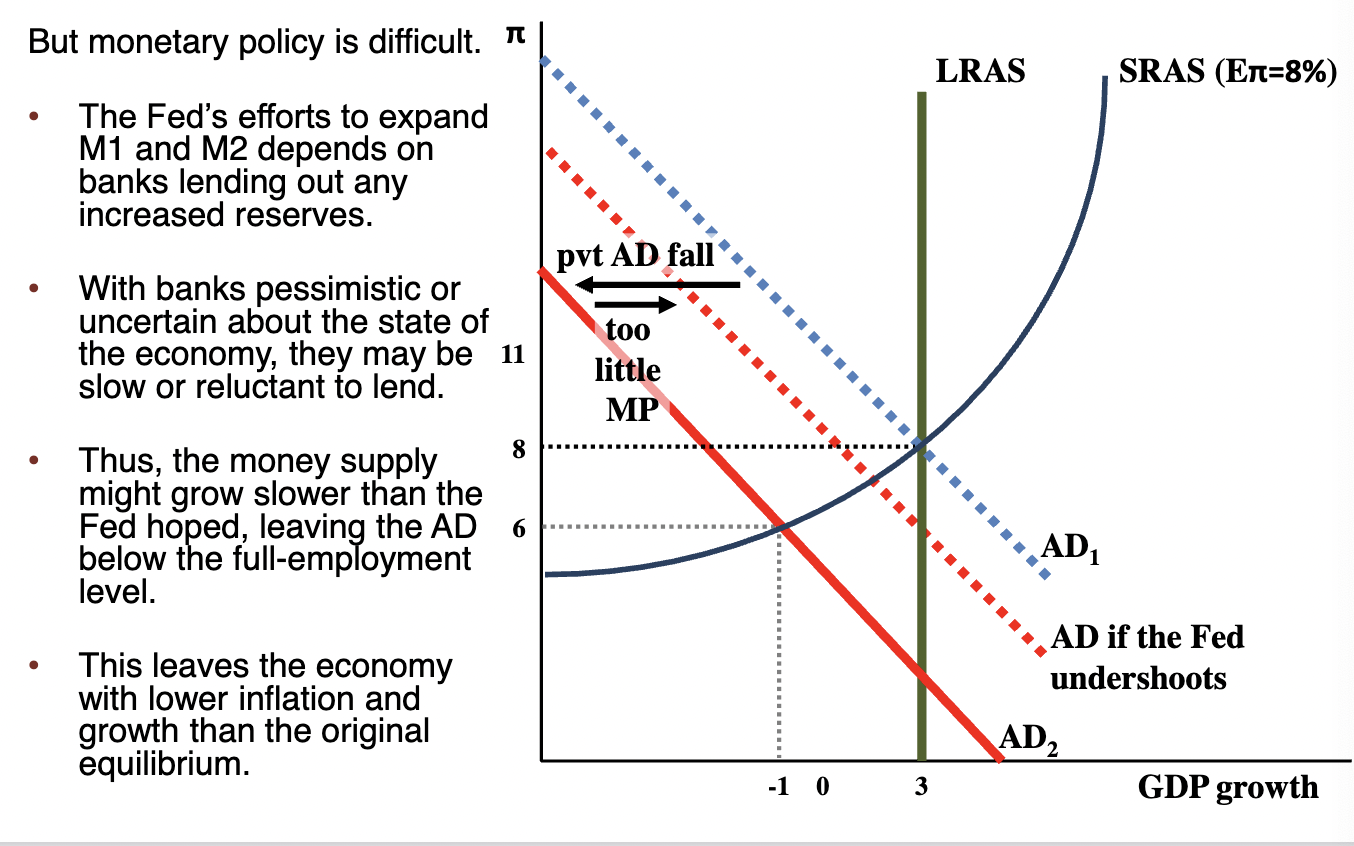

10. Central Banking is a Hard Job

- The U.S. Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) is often called on to combat recessions.

- There are lags between a decision by the Fed and the effects of the decision

- In the meantime, economic conditions may change-they are a “moving target”.

- Too much money leads to inflation

- Not enough money can lead to economic slowdown or recession.

Takeaways:

- Understanding incentives matter, because people pursue their self-interest in the context of their institutional environment.

- This involves looking at the marginal benefits and costs as people face tradeoffs in a world of scarcity.

- These basic principles apply across countries, making it important that policymakers have a good understanding of their applications.

- Economics is also linked to everyday life-your job, personal finances, debt, inflation, recession.

Chapter 2: The Power of Trade and Comparitive Advantage

Introduction:

Benefits of Trade:

- Trade makes people better off when preferences differ

- Trade increases productivity through specialization and the division of knowledge

- Trade increases productivity through comparative advantage

Trade and Preferences:

- Ex. Creator of ebay put up a random object, a broken pen as a way to try out the website, and actually got a buyer who was a collector of broken pens.

- People’s willingness to pay for goods is subjective.

- Trade moves goods from people who value them less to people who value them more.

- Trade makes poeple with different preferences better off.

- Trade creates value due to people’s diverse preferences.

Trade and the Division of Labor

- People enjoy different endowments of skills and factors of production

- Trade allows people to specialize in producing goods they are efficient at making

- This specialization creates opportunities to increase productivity in the long run.

- Adam Smith: Whenever a person saunters from one employment to another, when he first begins his work, his mind does not go to it, until they are more focused on the task at hand. Smith says that labor is facilitated and abridged by the proper machinery and that people are more likely to be able to complete a task when their whole attention of their minds is directed towards that single object than when dissipated among many things.

Specialization:

Increased Productivity

- We can produce more through trade than by individual production

- People who specialize develop skills and knowledge about their field

Because they sell large quantities, people who specialize can take advantage of specialized and large-scale equipment.

Division of Knowledge:

- Without specialization, each person produces their own food, clothing, and so on

- Each person has about the same knowledge as everybody else.

- The combined knowledge of a society is not much more than that of a single person.

- Limits how much we know about society.

- With specialization, much more knowledge is used than could exist in a single brain.

- More room for people to discover more things in their field and cover a larger sphere of specialization.

- Knowledge increases productivity, so specialization increase total output

- Knowledge increases productivity, so specialization increases total output.

- Every increase in world trade is an opportunity to increase the division of knowledge.

Tools of Economic Science:

- Assumptions

- Simplify the complex world and make it easier to understand

- Models

- Stylized representations of a complex reality, abstracting from less relevant details to help us focus on relevant processes

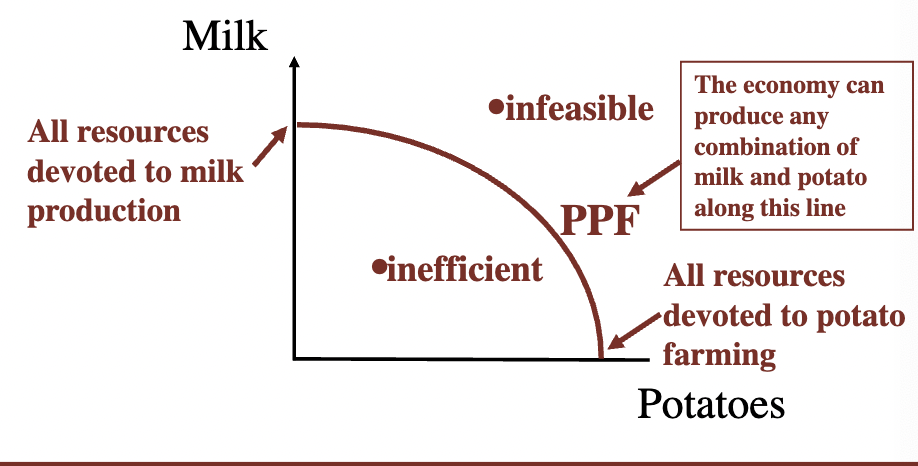

The Production Possibilities Frontier:

- A table or graph indicating all the combinations of goods that an individual or country can produce with a given endowment of inputs and technology

- Example:

- A table or graph indicating all the combinations of goods that an individual or country can produce with a given endowment of inputs and technology

- Assumptions:

- Abstracts the entire economy into two goods

- Snapshot of an economy at one time

- Though the PPF is a snapshot, we can shift it to indicate the effect of changes to an economy’s endowment of inputs and technology

- How would our PPF change with a breakthrough in military technology?

- Improved military tech will allow for more gun production but will have no effect on the amount of domestic goods (“butter”) it can produce. An increase in military tech can allow a society to produce more butter for a given level of guns, since it reduces the amont of resources needed to make that amount of guns

- The PPF indicates all the combinations of goods that an individual or country can produce with a given endowment of inputs and technology (embodies the problem of scarcity)

- Shows the trade-off between producing different goods (the opportunity cost of producing one good in terms of the other

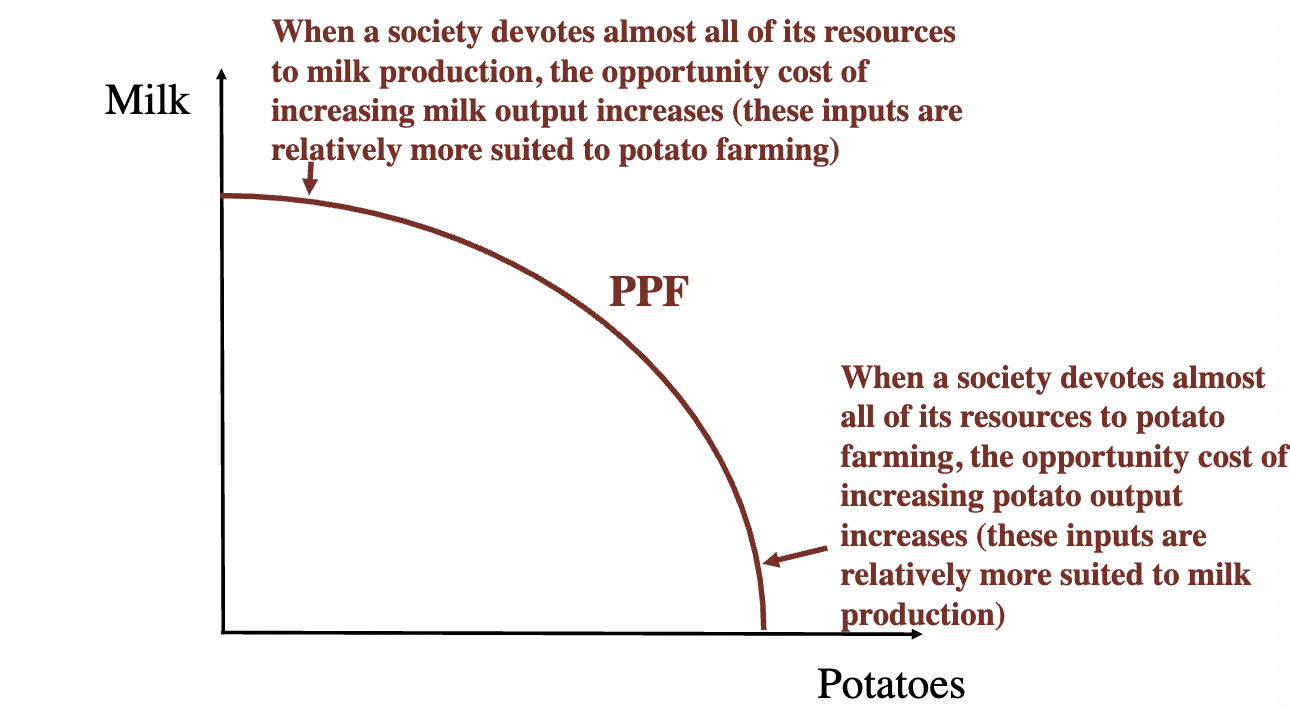

- Opportunity cost of producing each good may differ depending on where an economy sits along the PPF, because different resources are differently suited to producing different goods

- The PPF’s slope will show the marginal rate of transformation between the different goods

January 17th Notes:

Chapter Two Continued

- Nations’ PPFS will have a bowed shape reflecting the differing opportunity cost at different points along the PPF

The PPF and Opportunity Cost:

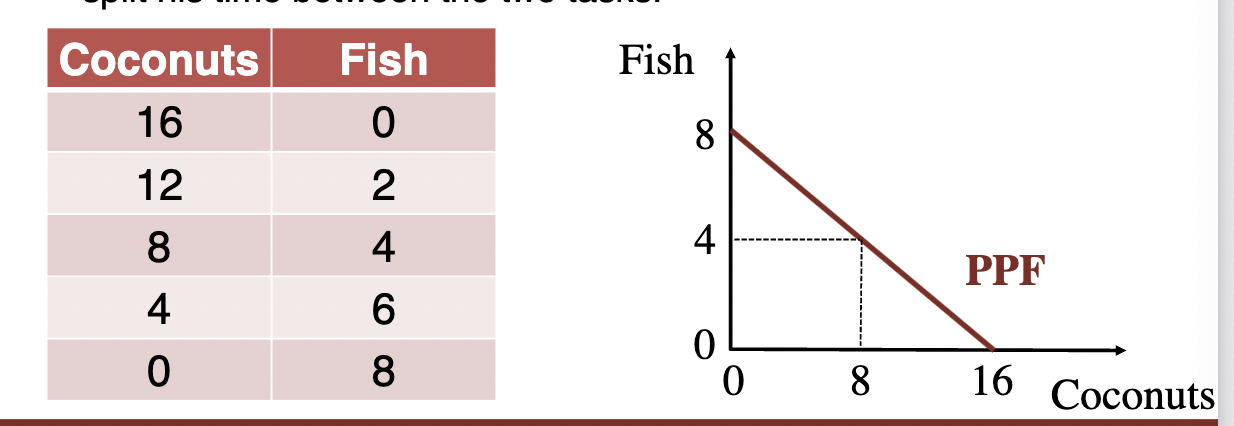

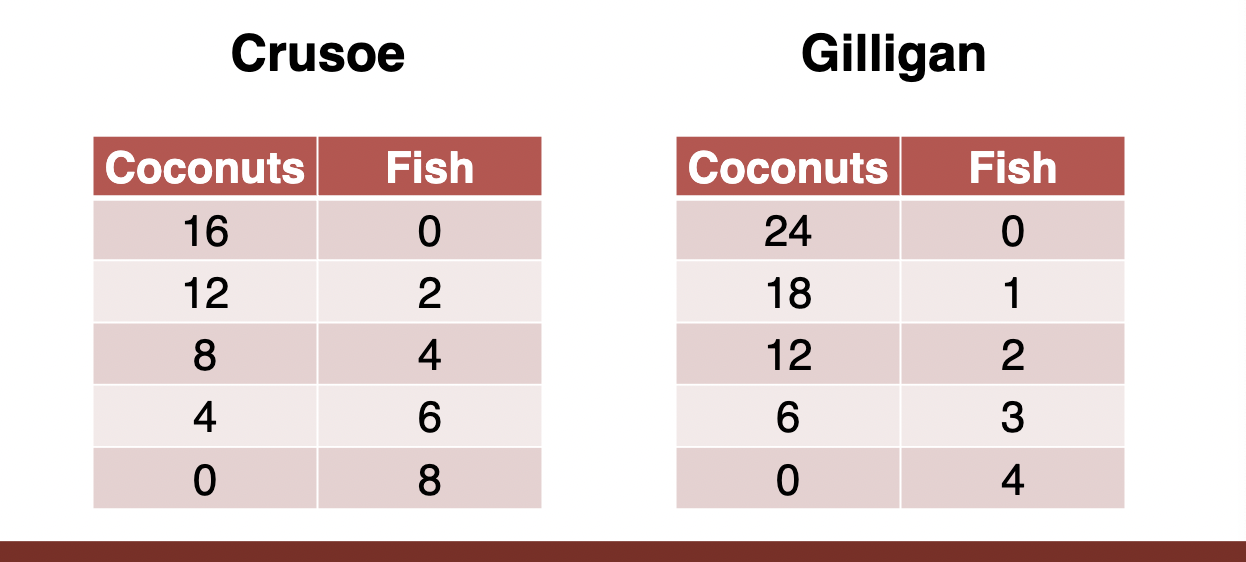

- Ex. Crusoe shipwrecked on an island where the only resource is his labor (8 hours). He discovers he can catch 1 fish per hour/harvest 1 coconut every 30 minutes.

- He can devote all 8 hours to coconuts while catching no fish, or spend 8 hours fishing and harvest no coconuts.

- O.C. of coconut= 8 fish/16 coconuts=½ fish

- O.C. of fish = 16 coconuts/8 fish = 2 coconuts

Absolute Advantage:

- The ability to produce the same good using fewer inputs than another producer.

- Ex. Cruscoue has an absolute advantage in catching fish, and Gilligan in catching coconuts, so they can each specialize.

Comparative Advantage:

- The cost of something is what you give up to get it, the opportunity cost for getting it.

- Ex. If Gilligan doesn’t have the absolute advantage for anything say the numbers could conclude:

- Gilligan: O.C. of coconut = 4f/12c = ⅓ fish and O.C. of fish = 12c/4f = 3 coconuts

- Crusoe: O.C. of coconut = ½ fish and O.C. of fish = 2 coconuts

- Even though it takes Gilligan longer to harvest a coconut, he faces a lower O.C. for doing so. This means Gilligan has the comparative advantage in harvesting coconuts because it takes him less time to get a coconut.

- Definition: Producing a good at the lowest opportunity cost compared to other producers

- Rational people will only participate in trades that make them better off. Therefore, trades where the marginal benefit are greater than or equal to the marginal cost.

- Trade can only take place at rates between either party’s opportunity cost of producing both goods for themselves.

- For countries: Comparative advantage means that all countries have a comparative advantage if they produce goods that they can make at a lower opportunity cost.

Absolute and Comparitive Advantage:

- To benefit from trade, a country doesn’t need to have an absolute advantage.

- A country can benefit from trade if it has a comparative advantage and every country will always have some comparative advantage producing something.

Wages:

- Trade raises wages to the highest levels allowed by a country’s productivity (wages will be higher in high-productivity countries than low-productivity countries).

Trade and Globalization:

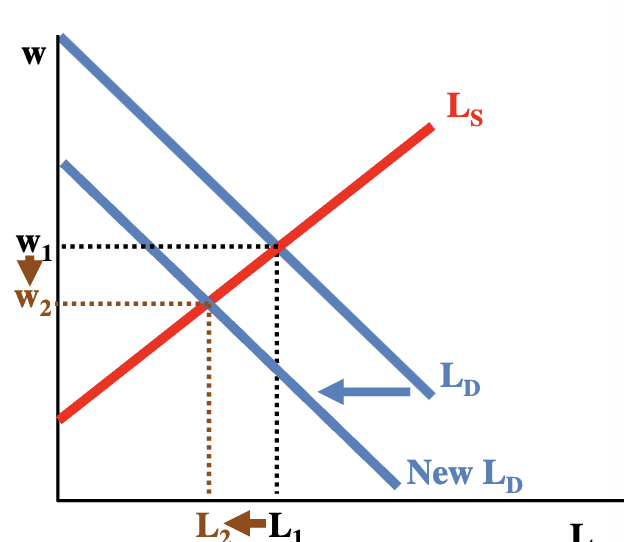

- Wages rise in high-demand industries and fall in low-demand industries

- Workers will move from low-wage to high-wage industries

- People have differing skills they may have cultivated for whole careers. If no compensation is provided, individuals may thus be hurt as their country embraces free trade.

- At a society-wide level, the gains exceed the losses

Chapter Three-Supply and Demand:

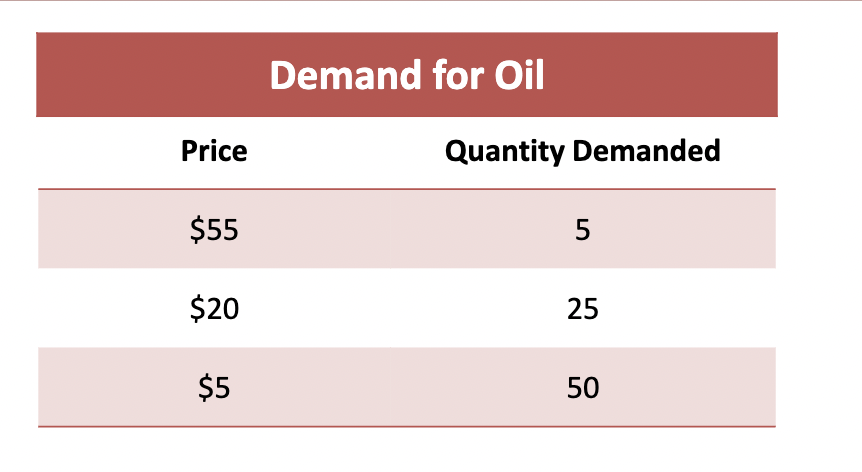

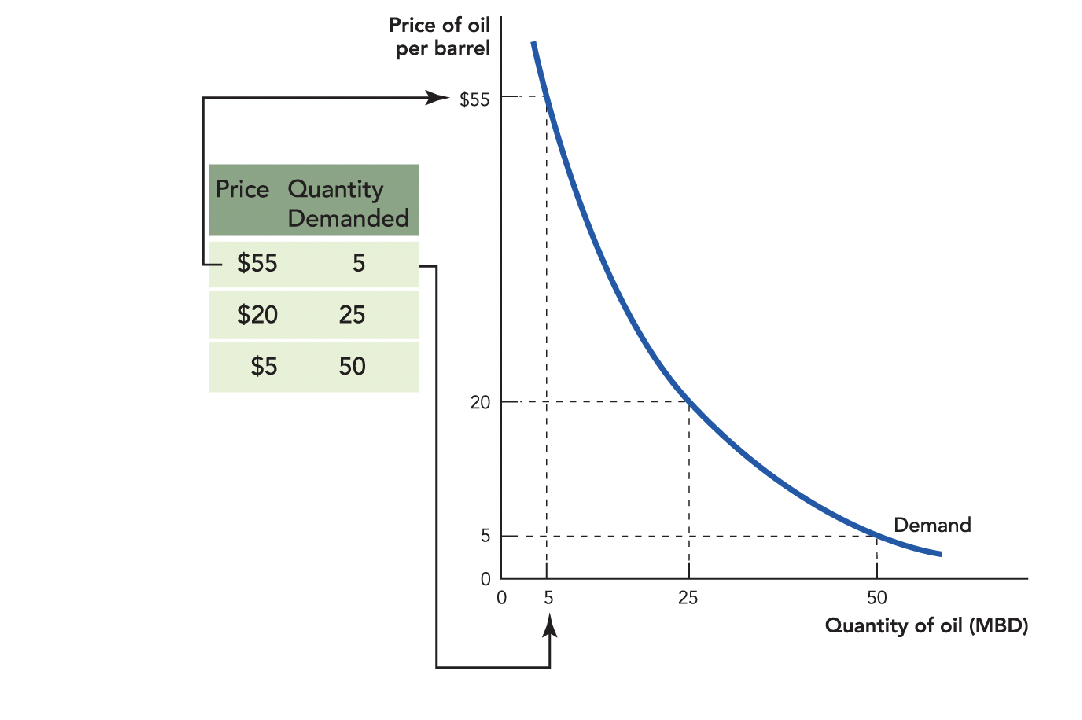

- Demand Curve: A function that shows the quantity demanded at different prices.

- Quantity demanded: The quantity that buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price.

Demand:

- Data for demand can be used to construct a demand curve

Individual Demand Curve:

- A graph plotting the quantity of an item that someone plans to buy at each price.

- Reflects the question that buyers face everyday: At this price, what quantity should I buy?

- An individual demand curve holds other things constant.

- Ex. Gas costs $3 per gallon, so how much gas should a person buy?

Textbook Notes:

- Economists refer to demand as all possible combinations of prices and quantities in the market.

- What happens to value when a good is transferred from a person who does not value it very much to someone who values it a lot? It increases the value.

- If Kyle voluntarily sells a used guitar to Tona for $800, it must be that:

Tona values the guitar more than Kyle does.

Chapter 1 Review:

Key Terms:

- Incentives: Rewards and penalties that motivate behavior.

- Scarcity: The inevitability of trade-offs is the consequence of a big fact about the world.

- Opportunity Cost: The value of the opportunities lost.

- Great Economic Problem: How we arrange our scarce resources to satisfy as many of our wants as possible.

- Inflation: An increase in the general level of prices.

Other Takeaways:

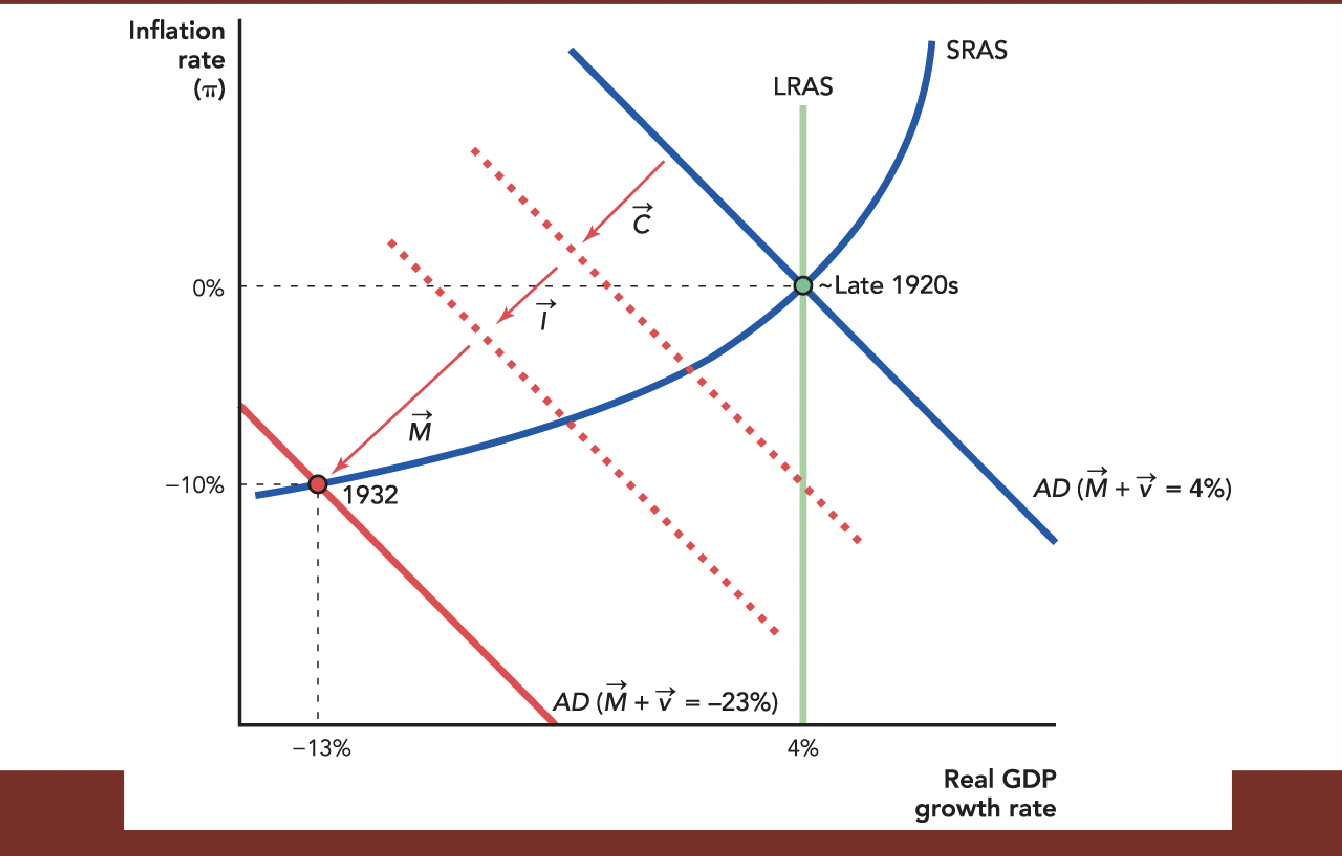

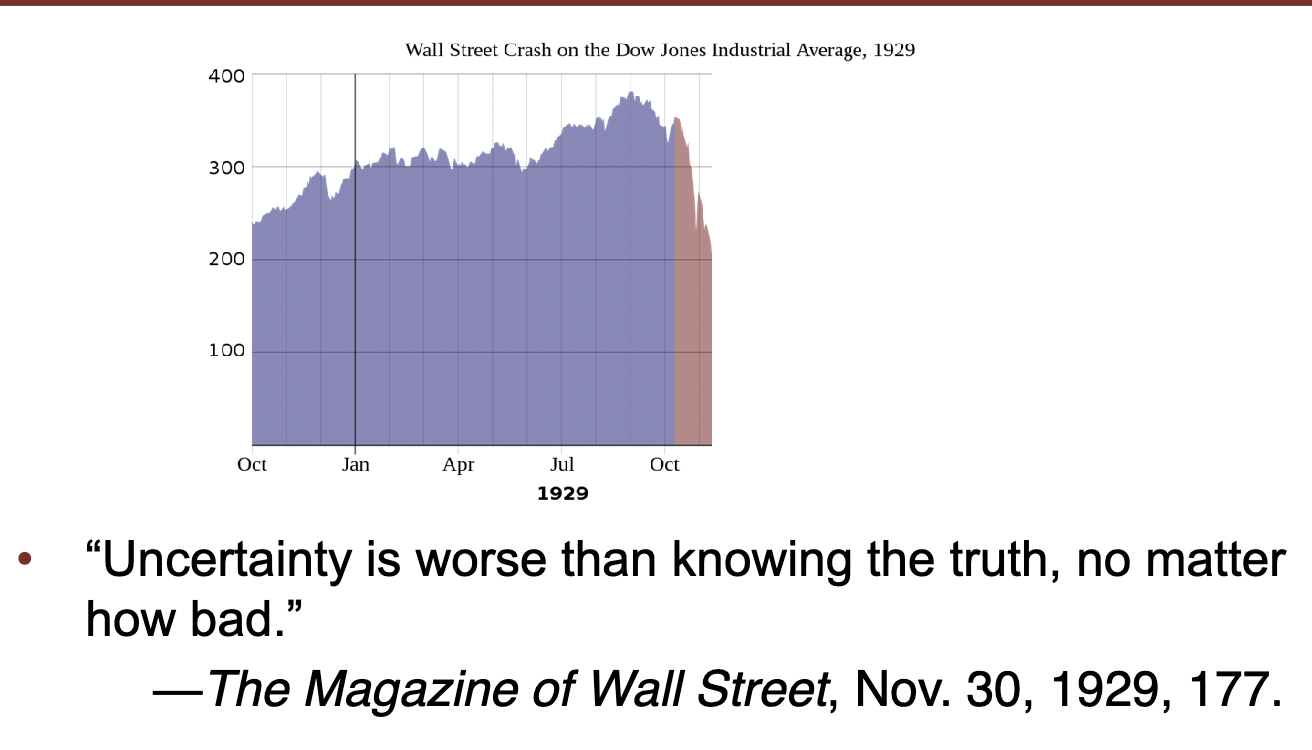

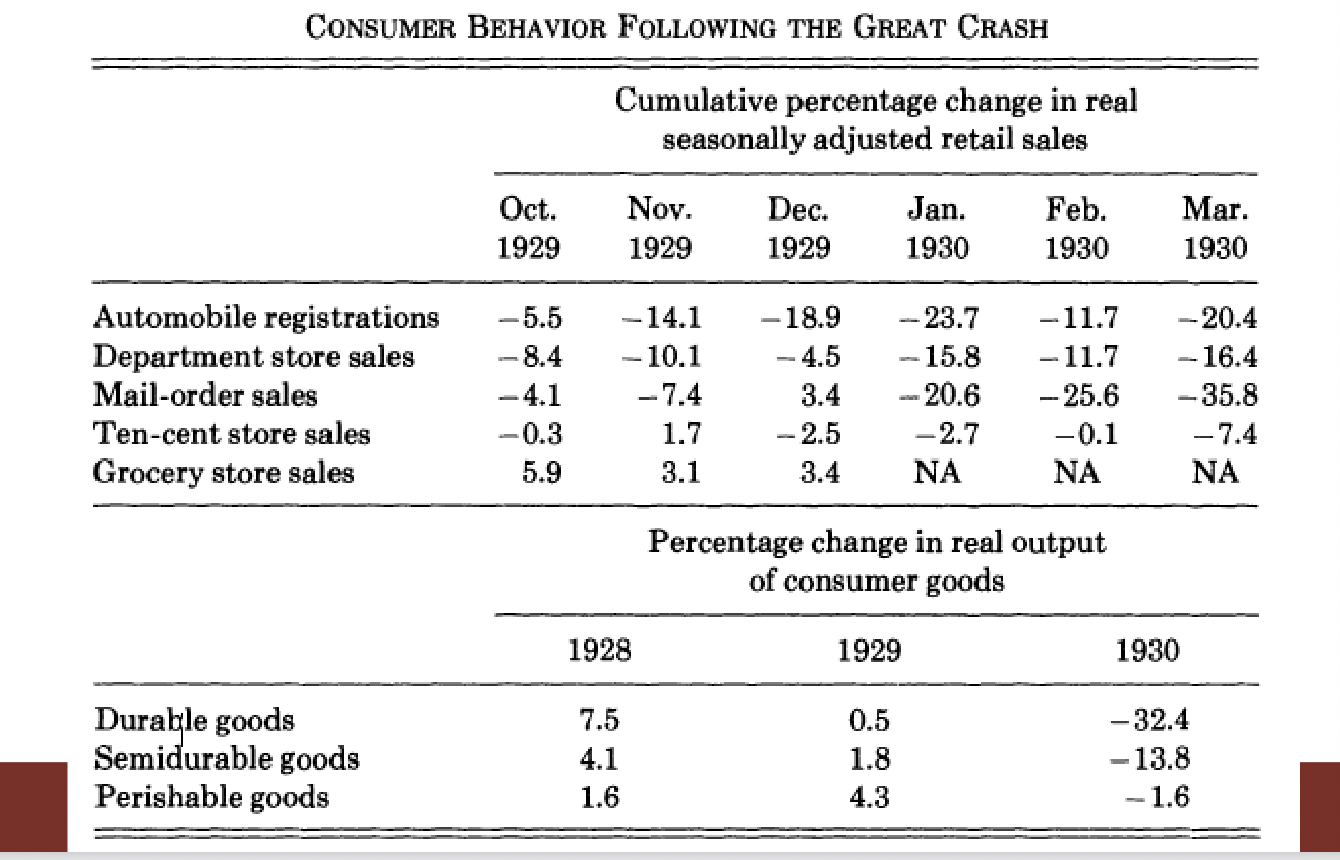

- It is claimed in the textbook that part of the reason that the Great Depression was so destructive was that economists didn’t understand how to use government policy very well in the 1930s.

Chapter 2 Review:

Takeaway:

- Simple trade makes people better of when preferences differ, but the true power of trade occurs when trade leads to specialization. Specialization creates enormous increases in productivity.

- International trade is trade across political borders. The theory of comparitive advantage explains how a country, just like a person, can increase its standard of living by speciallizing in what it can make at low opportunity cost.

Key Terms:

- Absolute advantage: A country has absolute advantage in production if it can produce the same good using fewer inputs than another country.

- Production Possibilities Frontier: Shows all the combinations of computers and shirts that a country or business can produce given its productivity and supply of inputs.

- Comparitive Advantage: One country/business has the lower opportunity cost in producing a good, so it therefore has a comparative advantage in producing that good.

Chapter 3 Review:

Key Terms:

- Demand Curve: A function that shows the quantity demanded at different prices.

- Quantity Demanded: The quantity that buyers are willing and able to buy at a particular price.

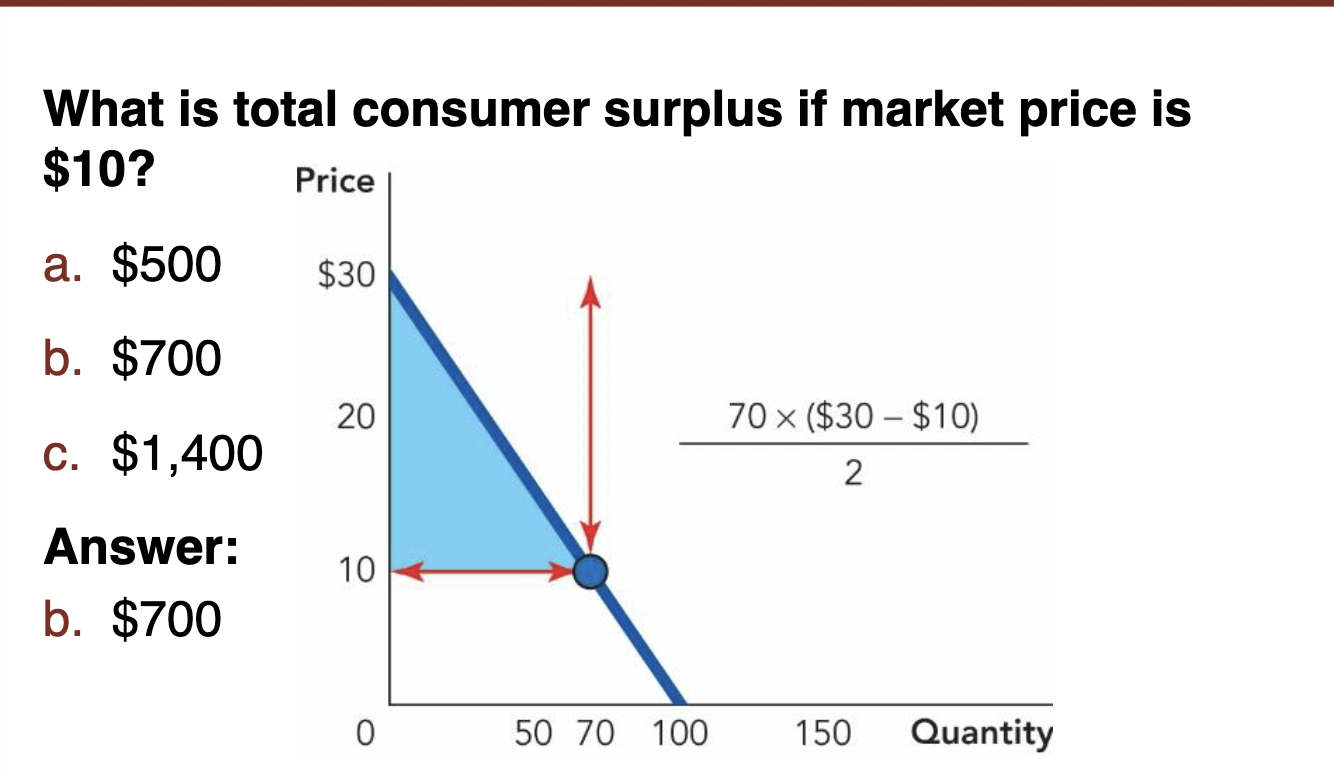

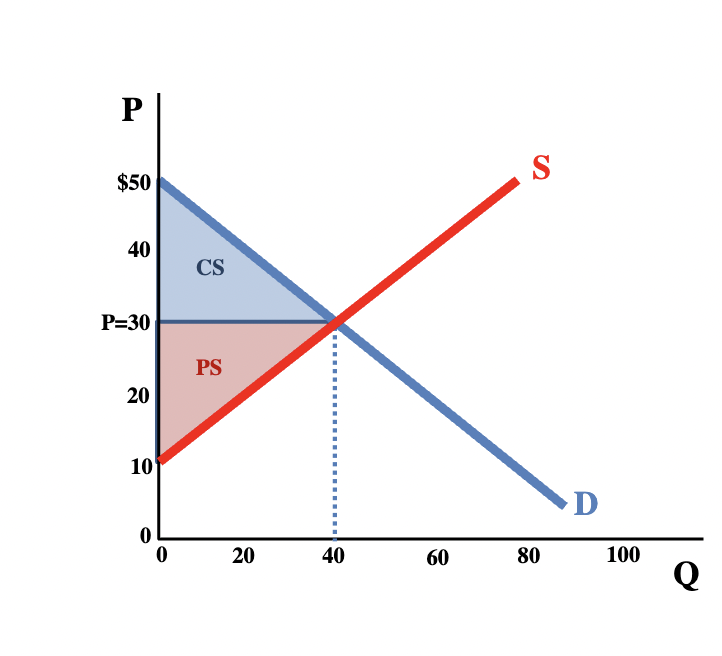

- Consumer Surplus: The consumer’s gain from the exchange.

- Total Consumer Surplus: Found by adding up consumer surplus for each consumer and for each unit. On a graph, it is the shaded area beneath the demand curve and above the price.

- An increase in demand shifts the demand curve outward, up and to the right. On the other hand, a decrease in demand shifts the demand inward, down and to the left.

- Important Demand Shifters:

- Income

- Population

- Price of substitutes

- Price of complements

- Expectations

- Tastes

- Normal Good: When an increase in income increases the demand of a good, we say that good is a normal good.

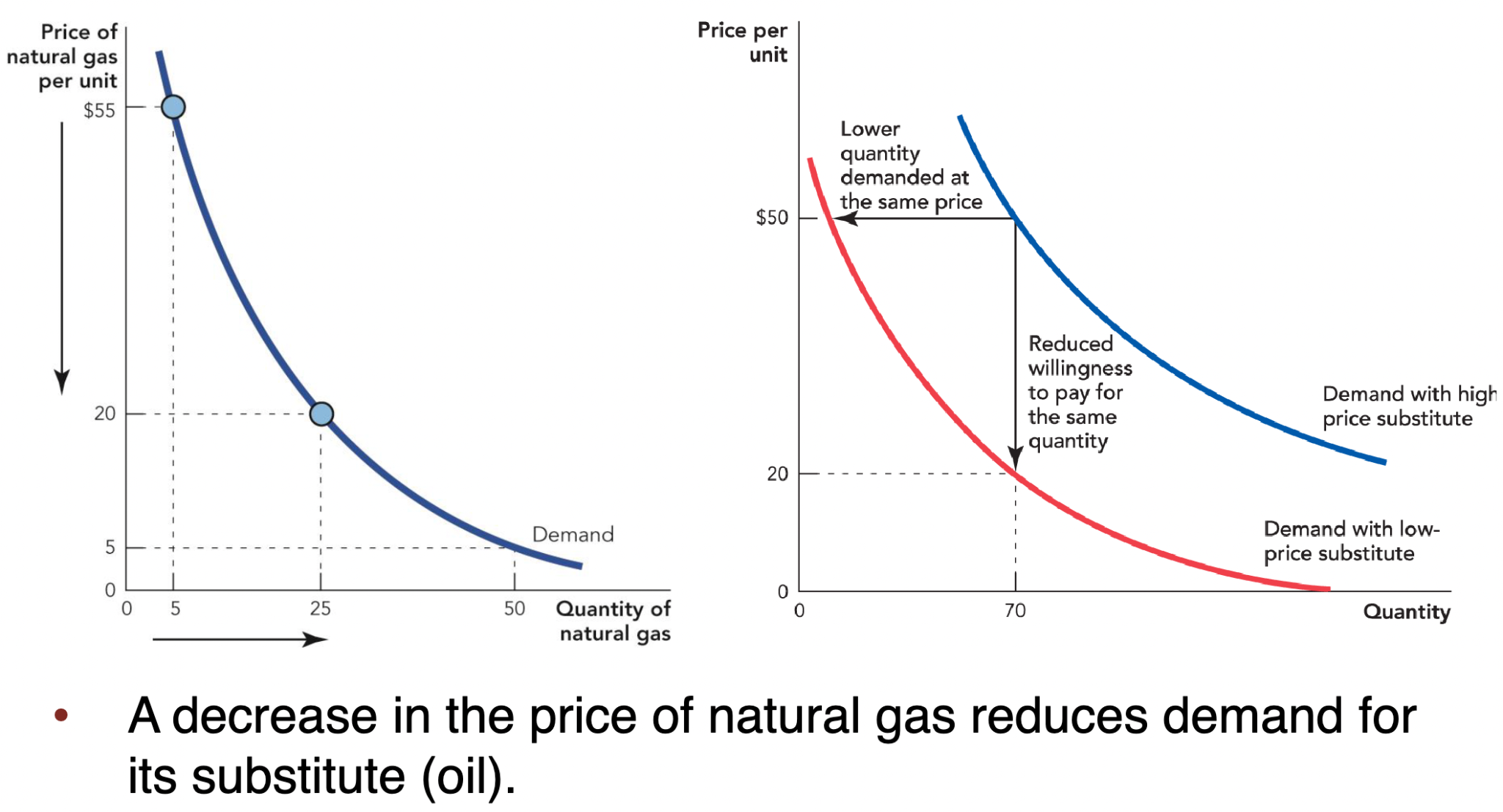

- Substitute: Two goods for which a decrease in the price of one leads to a decrease in demand for the other.

- Complements: Goods that go well together. Two goods for which a decrease in the price of one leads to an increase in demand for the other (ex. Peanut butter and jelly).

- Supply Curve: A function that shows the quantity supplied at different prices. The higher the price, the greater the quantity supplied.

- Quantity Supplied: The quantity that sellers are willing and able to sell at a particular price.

- Total producer surplus: An amount measured by the area above the supply curve and below the price up to the quantity traded.

Takeaways:

- Consumer surplus measures the consumer’s benefit from trade, and producer surplus measures the producer’s benefit from trade.

- Decrease in costs: Shifts the supply curve down and to the right

- Increase in costs: Shifts the supply curve up and to the left

- An increase in supply means that sellers are willing to sell a greater quantity at the same price, or, equivalently, they are willing to sell a given quantity at a lower price.

Quiz:

Go back to 16,18, and 19

January 19th Notes:

Chapter 3-Supply and Demand Continued

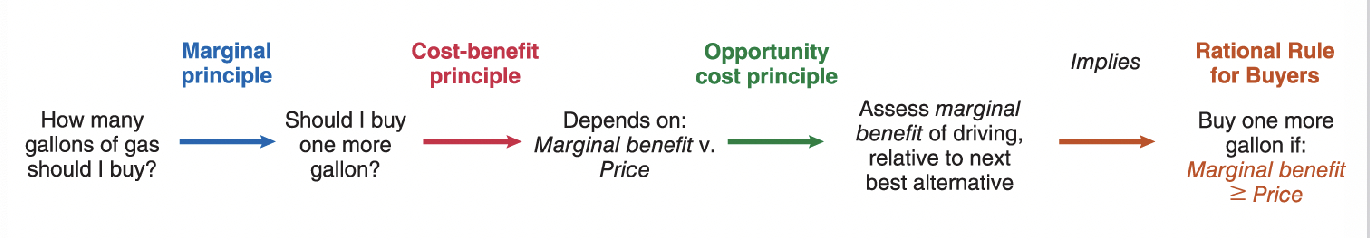

- The Marginal Principle:

- Ex. What are Darren’s marginal benefits for each additional gallon of gas?

- Gas is selling for $2.99. As for the marginal principle, Darren would consider each additional gallon of gas separately.

- The cost benefit principle: Darren compared the marginal cost to the marginal benefit for each gallon of gas.

- The opportunity cost principle: When Darren evaluated his marginal benefits, he compared the benefits to the next best alternative.

- The Rational Rule for Buyers: Buy more of an item if its marginal benefit is greater than (or equal to) the price.

- Keep buying until price = marginal benefit

- As buyers experiment, they will typically act as if they follow this analysis, intuitively purchasing goods up to the point where price = marginal benefit.

Holding Other Things Constant:

- When illustrating an individual demand curve, we ask how much we would be willing to purchase at each price, holding other things constant.

- Things other than price can influence demand. Demand for gas, for example, may change if someone buys a more fuel-efficient car.

- Everything is interdependent.

- First, we want to consider what occurs when the price changes.

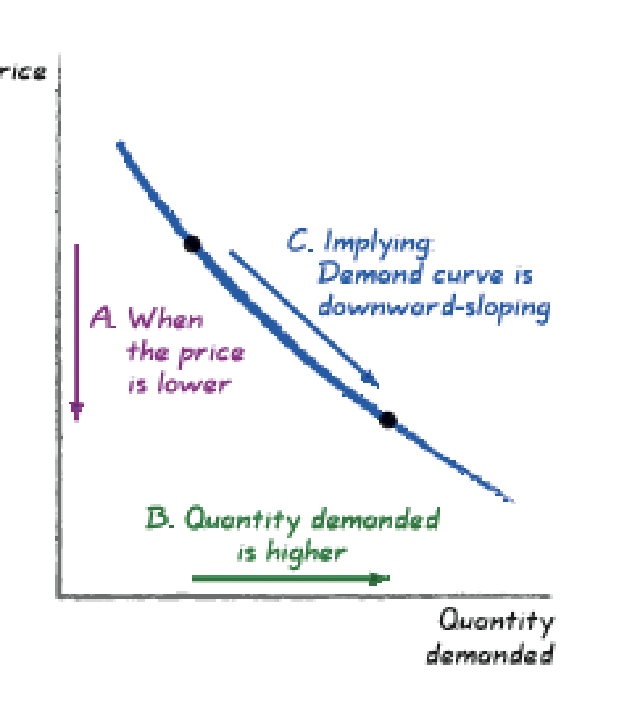

The Law of Demand:

- The quantity demanded is higher when the price is lower - holding other things constant!

Rational Rule

- → price = marginal benefit

- → demand curve = marginal benefit curve

- Diminishing marginal benefit – each additional unit yields a smaller marginal benefit than the previous unit.

Market Demand:

- Market Demand Curve: A graph plotting the total quantity of an item demanded by the entire market, at each price.

- It is the sum of the quantity demanded by each person.

- Individual demand curves are the building blocks of market demand.

- Market demand: The horizontal sum of individual demands

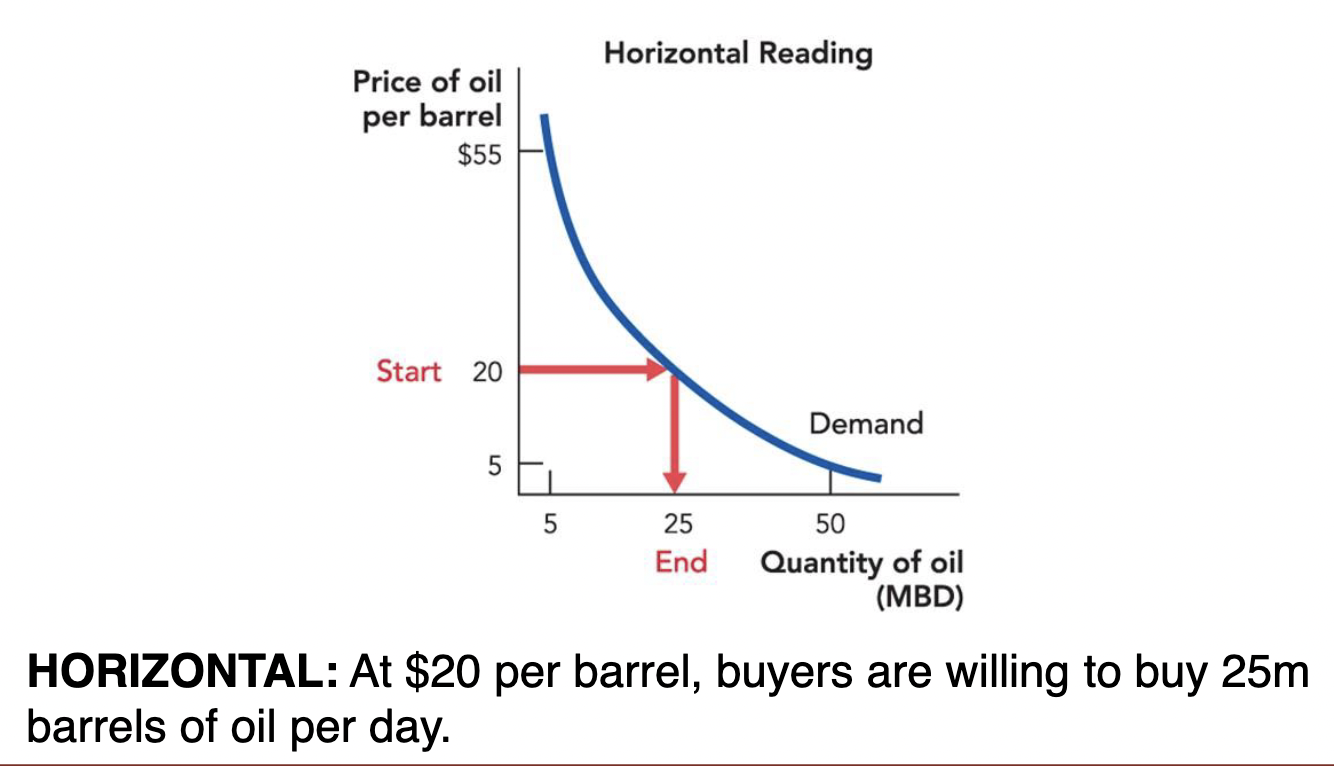

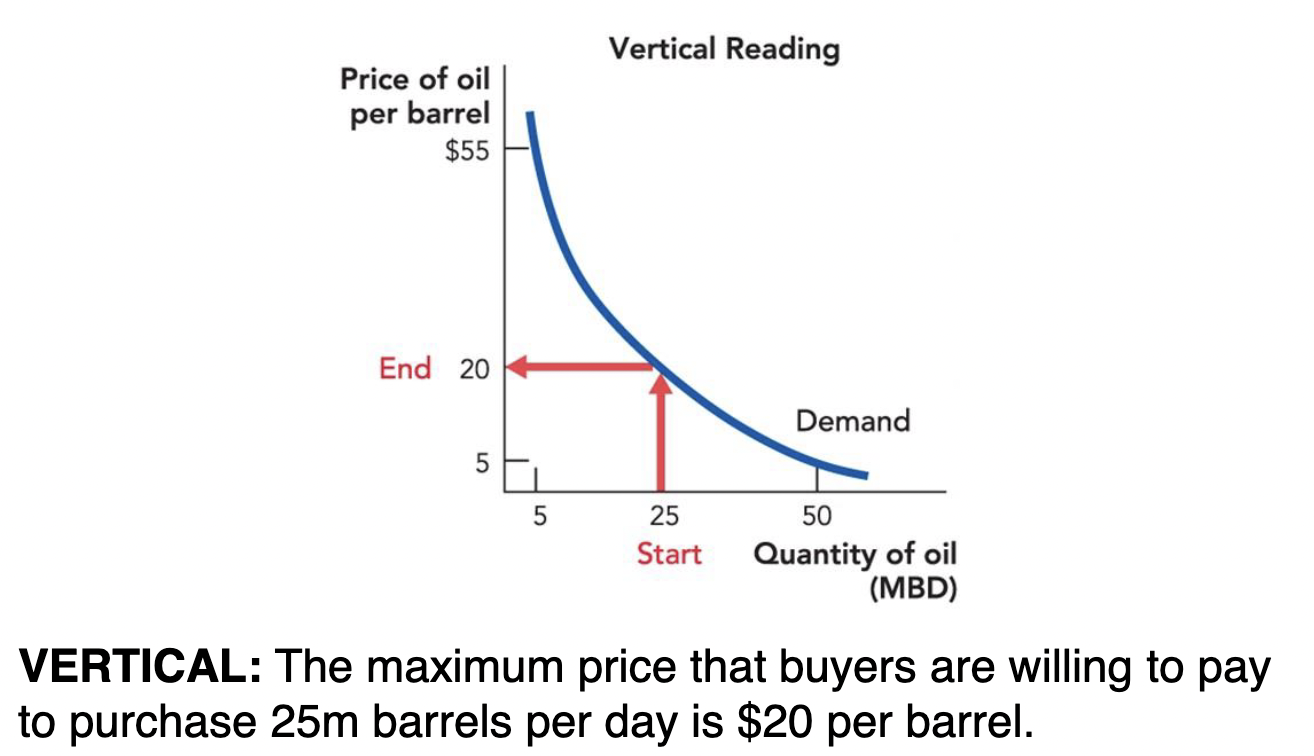

Reading a Demand Curve:

- Horizontally: At a given price, how much are people willing to buy?

- Vertically: What are people willing to pay for a given quantity?

Law of Demand:

- For nearly all goods, the demand curve will always be negatively sloped.

- The lower the price, the greater the quantity demanded

- Demand summarizes how consumers choose to use a good, given:

- Their preferences

- The possibilities for substitution

- Consumers will buy more oil at lower prices than at higher prices.

- When the price is high, consumers will use it only in its most valuable uses.

- As the price falls, consumers will also use oil in its less valued uses (ex. Instead of using oil for rubber duckies, can use wood in order to use higher-valued uses of oil for things like airplanes because there is no alternative).

Exceptions:

- Though the law of demand is one of the most fundamental principles in economics, there are a couple of exceptions such as

- Giften goods–cheap necessities, for which an increase in prices might cause consumers to buy more because they can no longer afford luxury substitutes (potatoes in Famine-era Ireland)--and

- Veblen goods– luxury goods whose value lays primarily in conspicuous consumption.

- But these exceptions are such edge-cases we can ignore them for most purposes.

Consumer Surplus:

- Consumer Surplus: The consumer’s gain from exchange; difference between the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a certain quantity and the market price.

- Total consumer surplus: The area beneath the demand curve and above the price.

- Example: In the example of Darren deciding how much gas to buy at $3, we would calculate his CS for his first gallon by subtracting this price from his WTP for this gallon ($5-$3=$2). For the second gallon, $4-$3=$1. His total CS would be $2+$1=$3.

January 22nd Notes:

- Change in Demand

- A shift in the demand schedule caused by changes in consumer tastes or conditions

- Movement along the demand curve

- A change in quantity demanded due to the movement from one point on a fixed demand curve to another along the same demand curve caused by change in price.

Factors that Shift Demand:

- Income

- When people get richer, they buy more

- When an increase in income increases the demand for a good, it is a normal good.

- Most goods are normal goods

- When an increase in income decreases the demand for a good, it is an inferior good.

- Population

- An increase in population will increase demand generally.

- A shift in subpopulations will change the demand for specific goods and services.

- Prices of Substitutes

- A substitute is a good that can be consumed instead of another good.

- Your demand for a good will increase if the price of substitute goods rises.

- Your demand for a good will decrease if the price of substitute goods decrease.

- Prices of Complements

- Complements are things that go well together.

- Your demand for a good will increase if the price of complementary goods decreases.

- Your demand for a good will decrease if the price of the complementary good rises.

- Expectations

- If you believe prices will rise (or supply will decrease), you will make your purchase today, increasing today’s demand.

- If you believe prices will fall, you will delay your purchase, decreasing today’s demand.

- Tastes

- Changes in preferences can shift demand curves.

- Companies spend billions of dollars each year attempting to influence our preferences through advertising.

- Social pressure can shift your demand curve

- Preferences are also affected by fads and fashion trends.

Producer Choice and Supply

Supply Curve:

- Supply Curve: A function that shows the quantity supplied at different prices.

- Quantity supplied: The quantity that sellers are willing and able to sell at a particular price.

Reading a Supply Curve:

A supply curve can be read-

- Horizontally: At a given price, how much are suppliers willing to sell?

- Vertically: To produce a given quantity, what price must sellers be paid?

Firm Decisions and the Individual Supply Curve:

Like consumers, firms choose what quantity to produce for markets based on

- The marginal principle

- The cost-benefit principle, and

- The opportunity cost principle

Choosing the best quantity to supply:

- The marginal principle: Decisions about quantities are best made incrementally.

- The cost benefit principle: Decisions depend on the balance of marginal benefits and marginal costs. Produce one more unit if the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost.

- The opportunity cost principle: When determining the marginal cost, you should

compare the cost of production to its next best option–not producing.

- Marginal cost does include variable costs …

- Variable costs are those costs that vary with the quantity of output, such as labor and raw materials.

- but does not include fixed costs.

- Fixed costs don’t vary when the quantity of output changes, they are incurred regardless of level of output.

Examples of what to consider when choosing the quantity to supply:

- How many units to supply

- Selling one more unit

- Selling one more unit depends on price versus marginal cost (cost-benefit principle).

- Calculate the marginal cost (opportunity cost principle).

- If the price is greater than the marginal cost, sell one more uniit in order to Maximize Profits!

Rational Rule:

- If maximizing profit, people will always keep selling until the price equals marginal cost.

- The supply curve, therefore, shows the quantity sold at every price, which is also the marginal cost.

Supply Curve Slope:

- The supply curve is upward sloping because of increasing marginal costs.

- As you increase the quantity you produce, the marginal cost of producing an extra unit rises because of the following:

1. Diminishing marginal product leads to rising marginal costs.

- Diminishing marginal product: The marginal product of an input declines as you use more of that input.

2. Rising input costs can also lead to rising marginal costs.

Market Supply Curve:

- A graph plotting the total quantity of an item supplied by the entire market, at each price.

- Market supply is the sum of the quantity supplied by each individual seller.

Law of Supply:

- The tendency for the quantity supplied to be higher when the price is higher (holding other things constant).

- Reflecting the diminishing marginal product, firms will tend to increase the quantity supplied as the price rises.

- As the price of oil rises, it becomes profitable to extract from more costly sources.

Shifts and Movements on Supply Curves:

- When the price changes, you are thinking about a movement along the supply curve.

- When other factors change you need to think about shifts in the supply curve.

Movements along the supply curve:

- A price change causes movement from one point on a fixed supply curve to another point on the same curve.

- Change in the quantity supplied: The change in quantity associated with movement along a supply curve.

Supply Curve Shifts:

- An increase in supply = shift to the right

- At each price, producers are willing to sell more.

- At each quantity, producers are willing to accept a lower price.

- Decrease in supply = shift to the left

- At each price, sellers will offer less

- At each quantity, sellers will demand a higher price

Factors that Shift Supply:

- Technological Innovations and the Price of Inputs

- Improvements in technology can reduce costs, thus increasing supply. A reduction in input prices reduces costs and thus has a similar effect.

- Taxes and Subsidies

- A tax on output has the same effect as an increase in costs.

- A subsidy is the reverse of tax

- Expectations

- Suppliers who expect prices to increase will store goods for future sale and sell less today. The expectation of an increase in price decreases supply and the supply curve shifts to the left.

- Entry or Exit of Producers

- Shifts the curve down and to the right. This also affects the market supply curve.

- Changes in Opportunity Costs:

- An increase in opportunity costs shifts the supply curve up and to the left

- If the price of wheat increases, the opportunity cost of growing soybeans increases Some farmers will shift away from producing soybeans and start producing wheat. The supply curve shifts soybeans to the left.

Consumer surplus formula:

½ x (market price-price)xquantity demanded

Producer surplus:

½ x (price given-minimum price) x min quantity demanded

Calculate the area between the price and the supply curve

Chapter Four Notes:

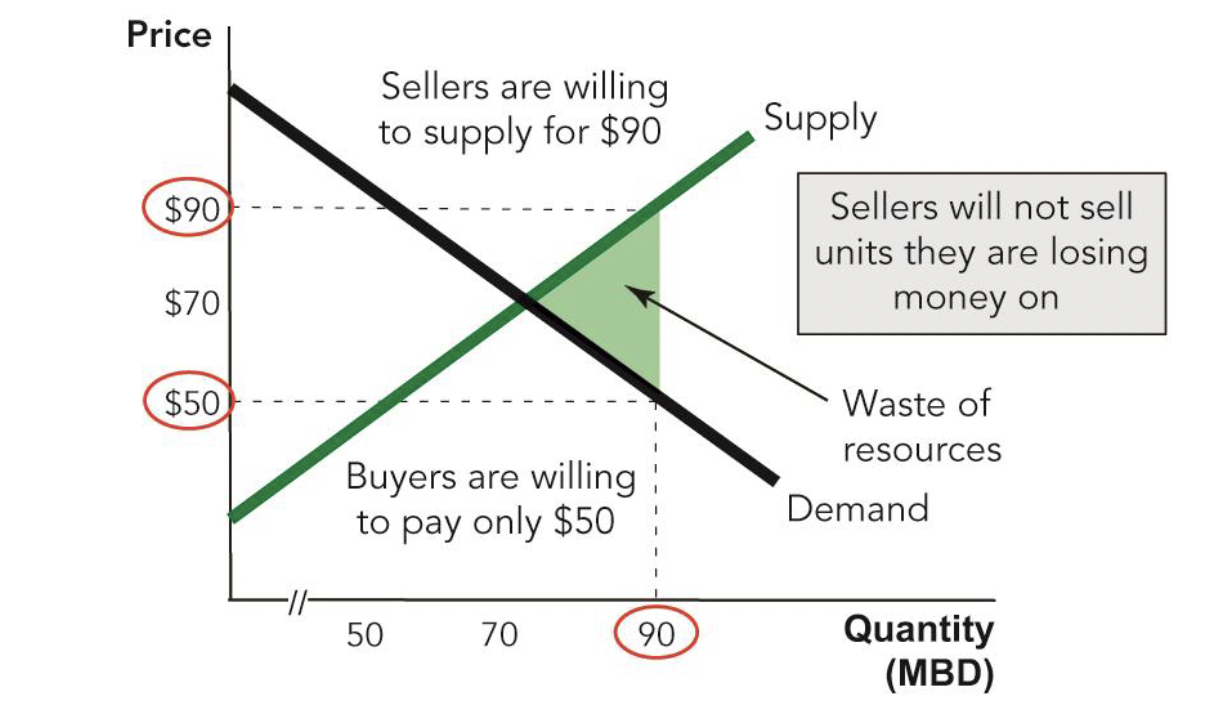

- Surplus: A situation in which the quantity supplied is greater than the quantity demanded.

- Competition will push prices down whenever there is a surplus. As competition pushes prices down, the quantity demanded will increase and the quantity supplied will decrease. Vice versa, competition will push prices up whenever there is a shortage. As prices are pushed up, the quantity supplied increases and the quantity demanded decreases until there is a price where there is no longer an incentive for prices to rise and equilibrium is restored.

- Equilibrium price: The price at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied.

- Equilibrium quantity: The quantity at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied.

- At equilibrium, neither buyers nor sellers have an incentive to change. At any other point, economic forces push prices and quantities back toward equilibrium.

- Shortage: A situation in which the quantity demanded is greater than the quantity supplied.

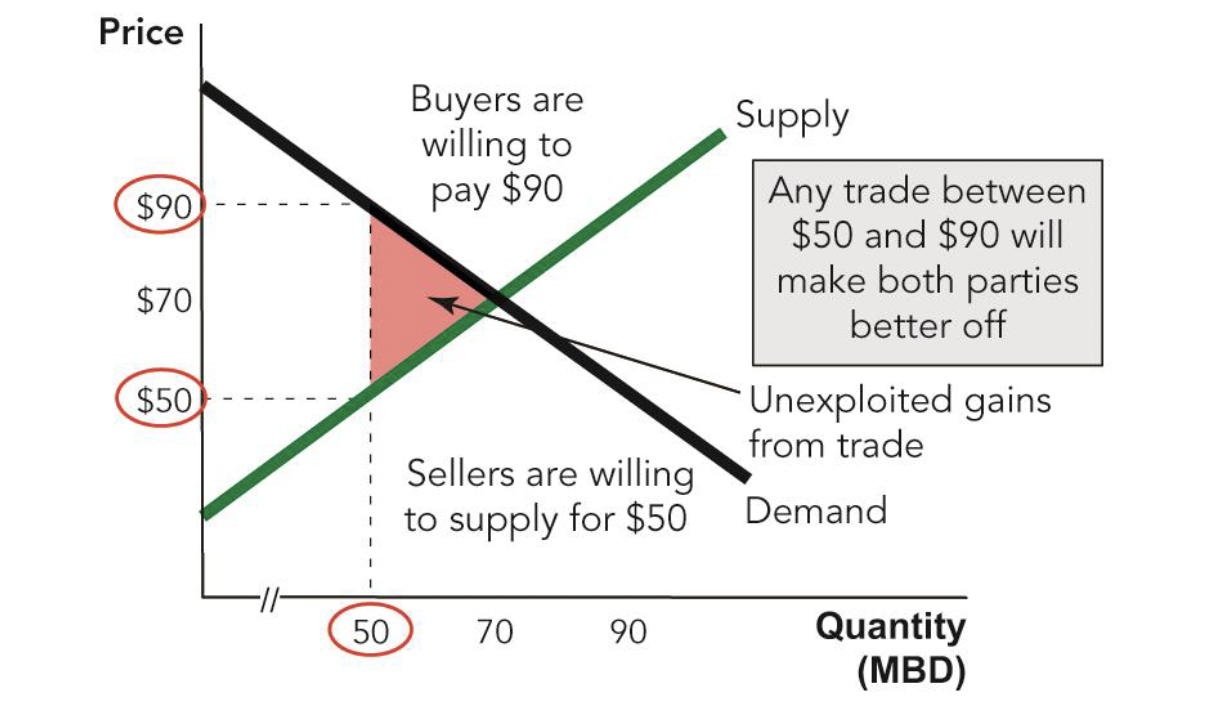

- When a free market maximizes the gains from trade, this means:

- The goods are bought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay.

- The goods are sold by the sellers with the lowest costs.

- There are no unexploited gains from trade and no wasteful trades.

(Together, these three conditions imply that the gains from trade are maximized)

- An increase in supply reduces the equilibrium price and increases the equilibrium quantity.

- An increase in supply = shift of the entire supply curve

- An increase in quantity supplied = movement along a fixed supply curve

Takeaways and Conclusions:

- Market competition brings about an equilibrium in which quantity supplied = quantity demanded.

- Only on price/quantity combination is a market equilibrium and this should be identifiable.

- Should understand and be able to explain the incentives that enforce market equilibrium.

- The sum of consumer and producer surplus (gains from trade) is maximized at the equilibrium price and quantity, and no other price/quantity combination maximizes consumer plus producer surplus

- A change in demand is not the same thing as a change in quantity demanded, and the same goes for a supply curve.

January 24th Notes:

Markets:

- Market: A group of buyers and sellers of a particular good or service.

- Competitive Market: A market in which there are many buyers and many sellers so that each has a negligible impact on the market price

—> Price takers buying and selling a homogeneous product

A.K.A. “perfect competition”

Other Market Structures:

- Monopoly: A market with only one seller market

- Seller controls price

- Oligopoly: A market with only a few sellers

- Not always aggressive competition

- Monopolistic Competition: A market with multiple sellers, each selling a slightly different product from its competitors.

What Markets Do:

- Markets organize economic activity by bringing potential buyers into contact with potential sellers.

- They determine:

- what gets produced.

- how much gets produced.

- who produces it.

- who receives it.

- at what price.

- Market outcomes are determined by the forces of supply and demand

- Remember that the demand curve indicated the Qd at each P.

- We can overlay this with the S curve, which shows the Qs at each P.

- The point where the S and D curves intersect shows the P where Qs=Qd

Equilibrium:

- Equilibrium occurs at the price where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied

- Equilibrium price: The price at which the market is in equilibrium

- Equilibrium quantity: The quantity demanded and supplied at equilibrium..

- Equilibrium price and quantity are the only factors that are stable in a free market.

- At any other point, economic forces push prices and quantities back at equilibrium.

- (In this class, focus is on equilibrium in perfectly competitive markets.

Adjustment Process: Surpluses

- Consider how markets will reach to a surplus.

- Surplus: A situation in which quantity supplied is greater than quantity demanded.

- Surpluses are seen where the price is greater than the equilibrium price.

- With Qs>Qd, firms will not be able to sell all their inventories.

- Some will lower their prices as they compete for customers.

- This will put a downward pressure on the price, eventually bringing the market to equilibrium.

Adjustment Process-Shortages:

- Shortage: A situation in which quantity demanded is greater than quantity supplied.

- Shortages are seen where the price is lower than the equilibrium price.

- With Qd>Qs, customers will not be able to buy everything they want at the market price.

- Some will offer sellers higher prices as they compete for scarce goods.

- This will put an upward pressure on price.

- Eventually bringing the market to equilibrium.

Equilibrium:

- Occurs when Qd=Qs

- Every buyer who wants the good at the equilibrium price can get it.

- Sellers can sell every unit they want to sell at the equilibrium price.

- Buyers have no incentive to bid up the price.

- Sellers have no incentive to lower prices.

Equilibrium:

- At equilibrium neither buyers nor sellers have an incentive to change.

- At any other point, economic forces push prices and quantities back toward equilibrium

- Equilibrium is the point at which there is no tendency for change.

- Equilibria are also stable in other market structures we discussed, but they will look different.

- There are regular supply- and demand-curve shifts.

- Each S and D curve only shows the Qs and Qd at each price holding all else equal.

- All else does not remain equal–remember all the soruces of S- and D-curve shifts.

- But we will always tend towards the new equilibria.

Equilibrium and Gains from Trade:

- A free market maximizes the gains from trade.

- Available goods are brought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay.

- Goods are sold by the sellers with the lowest costs.

- Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade or any wasteful trades.

- These three conditions imply that the gains from trade are maximized.

Welfare Economics:

- Definition: The study of how the allocation of resources affects economic well-being

- The allocation of resources refers to

- how much of each good is produced

- which producers produce it

- which consumers consume it

Consumer Surplus:

- The consumer’s gain from exchange–the difference between the buyer’s willingness to pay for a quantity of a good and the price actually paid for it

- CS=WTP-P

- Total CS is equal to the area under the demand curve but above the price from 0 to Q

Producer Surplus:

- Seller’s gain from exchange–the difference between the price the seller receives for a quantity of a good and the cost of producing it (including opportunity cost)

- PS=P-C

- Total PS is equal to the area under the price but above from 0 to Q

CS, PS, and Total Surplus:

- CS= (value to buyers)-(amount paid by buyers)=buyers’ gains from participating in the market

- PS=(amount received by sellers)-(cost to sellers)=sellers’ gains from participating in the market

- Total Surplus= CS+PS

- = total gains from participating in the market

- = value to buyers - cost to sellers

CS, PS, and Total Surplus

- TS=CS+PS

- Without taxes, notice that:

- TS=CS+PS

- TS=(WTP-P)+(P-Cost)

- TS=WTP-Cost

- If Q were below the market equilibrium, both consumers and producers would be worse off for each unit past it

- Beyond Qeq, MB<MC

Total Surplus and Market Efficiency:

- Think about how total surplus would differ if Q were any lower or higher than the equilibrium

Unexploited Gains from Trade:

Wasted Resources

- If the quantity traded is less than the equilibrium quantity some gains from trade will be lost.

Another Caveat:

- Free market equilibria may not maximize social welfare in markets with externalities

- Externalities are the uncompensated effects of one person’s actions on the well-being of a bystander

- These effects can be either positive or negative.

- With externalities of consumption, buyers’ demand curves do not fully account for a goods’ marginal benefits.

- With externalities of production, sellers’ supply curves do not fully account for a goods’ marginal costs.

- Thus, their cost-benefit judgements will not result in a socially efficient outcome.

- In markets with externalities, the government can sometimes improve outcomes by implementing policies that help internalize externalities:

- Implementing taxes or subsidies that make people take into account the full cost or benefit of each unit of a good.

- But this requires information that government often lacks, and can be hard to implement.

January 26th Notes:

Negative Externality in Production:

- If production of a good imposes costs on others, the social cost will be above the S curve to account for these external costs.

- The market equilibrium results in too high a Q.

Evidence from the Labratory:

- In fall 1955, Vernon Smith questioned how much the models of perfect competition actually reflect reality.

- In Spring 1956, Smith tested the supply and demand model in a lab

Predicting Market Changes:

- The consequences of shifts in demand and supply.

- The ways that changes in prices and quantities reveal whether demand or supply changed.

Set up supply and demand graph

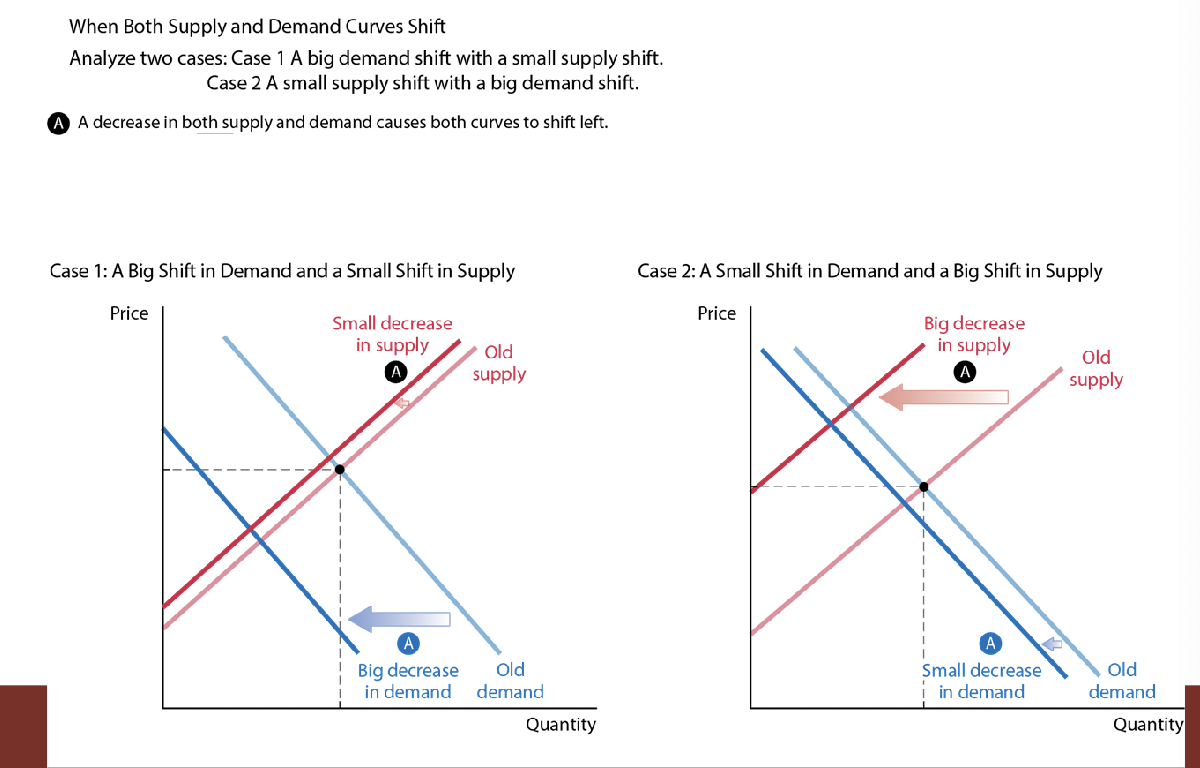

When Both Suply and Demand Shift:

- The conclusion is often unknown/depends on the situation.

- The change in supply might cause the price or quantity to move in one direction.

- The change in demand can cause it to move in the opposite direction.

- Example from the gasoline market:

- The U.S. entered a severe recession, and the price of oil rose sharply.

- A recession reduced the incomes of gas consumers, so demand shifted left.

- Higher oil prices raised costs for gasoline suppliers, so supply shifted left.

- This causes both curves to shift left.

- There was a decrease in quantity in either scenario because supply and demand curves are both shifting, pushing them to lower economies. The demand curve shifts down in price, and supply curve does the opposite.

- When supply and demand both shift, the effect on either price or quantity will be ambiguous

January 29th Notes:

Review:

Chapter 1:

- Incentives Matter:

- Incentives: Rewards and penalties that motivate behavior

- People respond to all kinds of incentives in predictable ways

- Incentives do not need to be monetary

- Good Institutions

- When markets work well, individuals pursuing their own interests also promote their self interest, led by an “invisible hand”

- When markets do not work well, government can change incentives with taxes, subsidies, or regulation

Opportunnity Cost Example:

- 70K (from quitting job)+25K (5% interest from 500K)=$95K total opportunity cost

- The day trader’s 100K accounting profit exceeded his 95K opportunity cost. He earned an economic profit of 5K.

Opportunity Costs:

- Some out of pocket costs are opportunity costs

- Opportunity costs don’t need to involve out of pocket financial costs

- Not all out of pocket costs are opportunity costs.

- Some nonfinancial costs are not opportunity costs.

Sunk Costs:

- Cost that has been incurred and cannot be reversed. Ignore sunk costs.

Thinking on the Margin:

- Choices are made by comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits. Compare the cost of consuming or producing one more unit of a good with the benefit of consuming or producing that one unit.

- Rational people only do something if the marginal benefit is greater than or equal to the cost.

- We ask about individuals’ willingness to pay to obtain the benefits of a particular good or avoid the costs of a particular bad. This willingness to pay is how much you value the good, independent of its market price.

Go over the principles

Ex.

Chapter 2:

Benefits of Trade:

- Trade makes people better off when preferences differ

- Trade increases productivity through specialization and the division of knowledge

- Trade increases productivity through comparative advantage

Specialization:

- Without specialization, each person produces their own food, clothing, and so on.

Division of knowledge:

- With specialization, much more knowledge is used than could exist in a single brain

Production Possibilities Frontier:

- A table or graph indicating all the combinations of goods that an individual/country can produce with a given existing inputs and technology

- Ask how each change would affect the society’s ability to produce each good, if the society specialized entirely in its production.

PPF and Opportunity Cost:

- The O.C. of one thing is the amount of the other that the industry/person does not produce.

- Helpful for understanding what it would look like when one person or industry does not have the absolute advantage in doing anything and to calculate the opportunity costs.

Absolute and Comparitive Advantage

- Countries benefit from trade if they have a comparative advantage rather than an absolute advantage

- Wages rise in high demand countries and fall in low-demand countries.

Market Outcomes:

- Determined by supply and demand

- The point where S and D curves intersect→equilibrium point

- At equilibrium neither buyers nor sellers have an incentive to change

- Economic forces push prices and quantites back toward equilibrium

- Equilibrium is the point where Qs=Qd

Equilibrium and Gains from Trade:

- Available goods are brought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay.

- Goods are sold by sellers with the lowest costs.

- Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade or any wasteful trades.

When Supply Increases:

- The S curve shift will cause a movement along the demand curve bringing about a lower price and higher quantity.

When Supply Decreases:

- The S curve shift will cause a movement along the demand curve bringing about a higher P and lower Q

When Demand Increases:

- The D curve will shift and cause a movement along the supply curve bringing about a higher P and Q

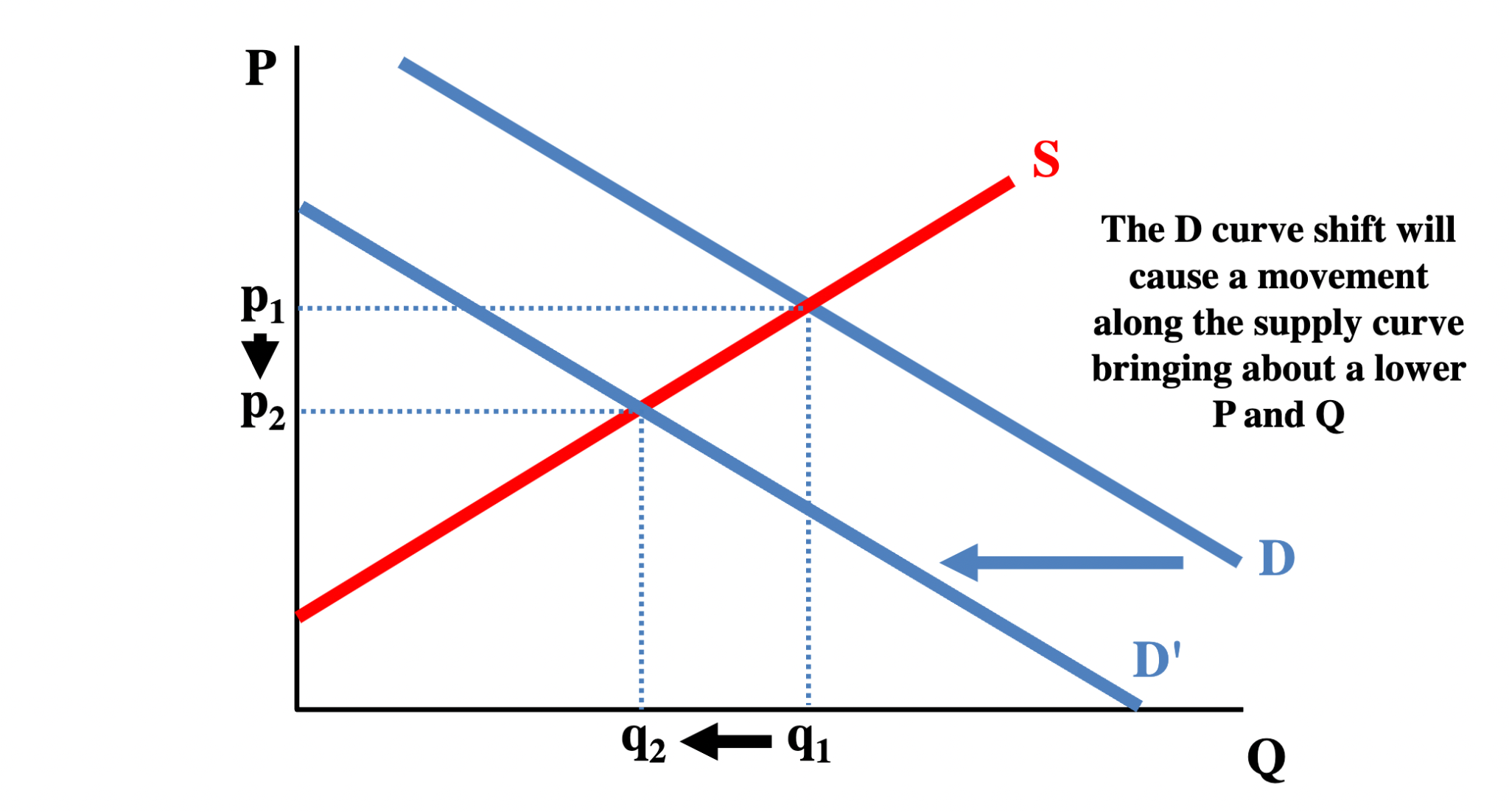

When Demand Decreases:

- The D curve shift will cause a movement along the supply curve bringing about a lower P and Q

When Supply and Demand both shift:

- Ex. When supply shifts right and demand shifts down. Small shift in quantity, big shift in price (price shifts down, quantity slightly shifts up)

Chapter 6 Notes:

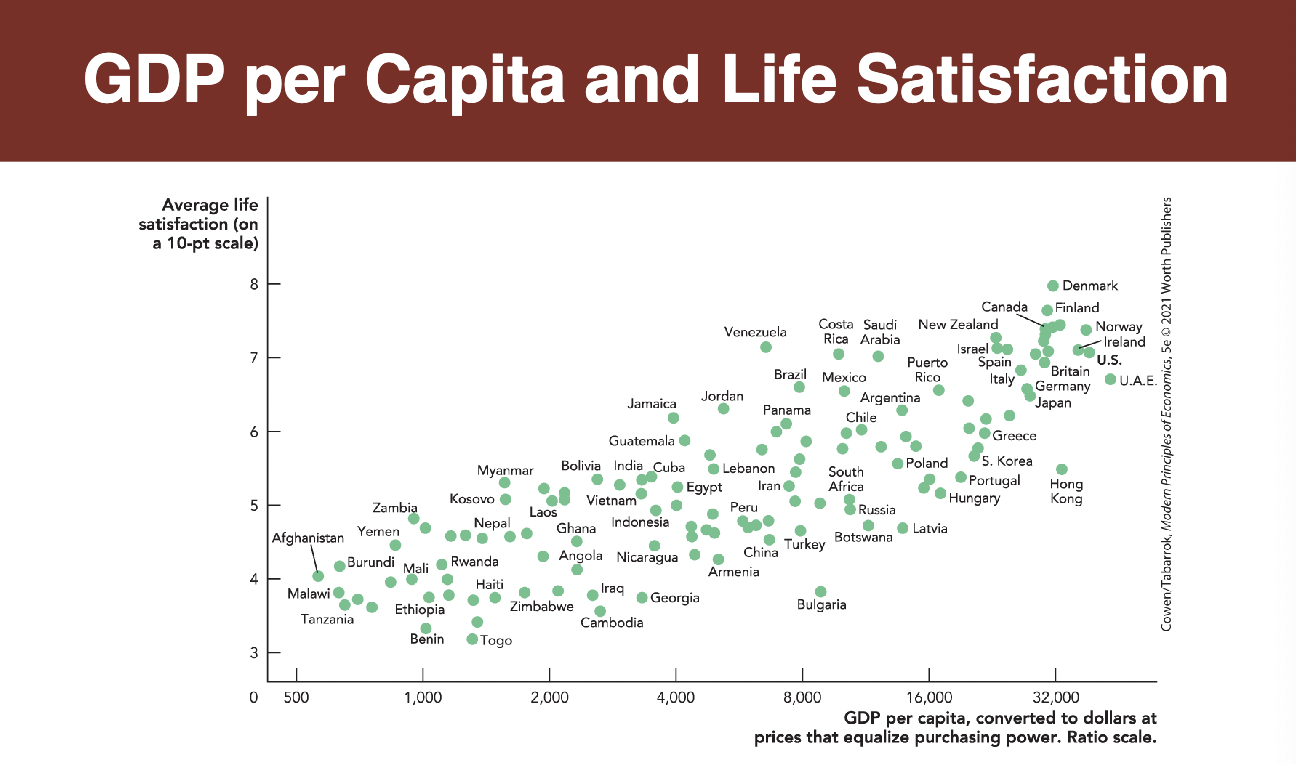

- Gross domestic product is the market value of all finished goods and services produced within a country in a year. GDP per capita is GDP divided by a country’s population.

- Intermediate goods and services: Some goods and services are sold to firms and then bundled or processed with other goods or services for sale at a later stage.

- The output of an economy includes both goods and services. Services provide a benefit to individuals without the production of tangible output

- Ex: U.S. GDP is about $21.4 trillion, the value of finished services is about $14.5 trillion and the value of finished goods is about $6.8 trillion (68% of GDP is from services so finished goods is 1-0.68=6.8 trillion of GDP).

- Gross national product: Very similar to GDP but GNP measures what is produced by the labor and property supplied by U.S. residents wherever in the world that labor or capital is located, rather than what is produced within the U.S. border.

- Compute percentage change as: (GDP2-GDP1)/GDP1 X 100=GDP growth rate for year 2

Terms with GDP:

- Calculated using prices at the time of sale. It is variables, such as nominal GDP, that have not been adjusted for changes in prices. Therefore, GDP from one year is calculated using that year’s prices. For example, 2018 nominal GDP is found by multiplying 2018 prices and 2018 quantities.

- Real variable: Variables such as real GDP, that have been adjusted for changes in prices by using the same set of prices in all time periods.

- GDP deflator: A price index that can be used to measure inflation. It equals (nominal GDP/Real GDP) x 100.

- Countries with low GDP but a high GDP per capita: UK and France and Country with a high GDP but a low GDP per capita: China

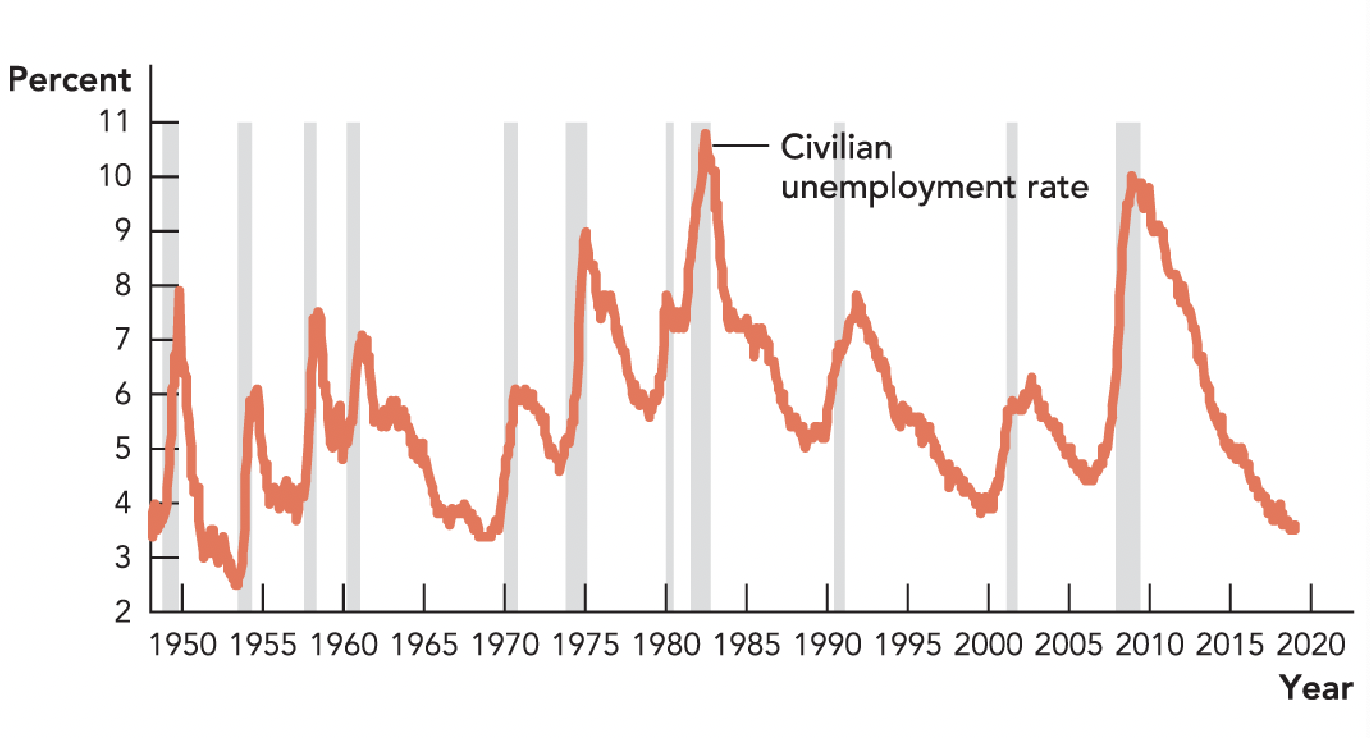

Cyclical and Short-Run Changes in GDP:

- Recessions: Significant, widespread declines in real GDP and employment–are of special concern to policymakers and the public.

- The National Bureau of Economic Reasearch is considered the most authoritative source on identifying U.S. recessions.

- The fluctuations of real GDP around its long-term trend, or “normal” growth rate, business fluctuations or business cycles.

- Business fluctuations: The short-run movements in real GDP around its long-term trend.

- Business Cycles: The short-run movements in real GDP around its long-term trend.

The Many Ways of Splitting GDP:

Two Common ways of splitting GDP-

- National spending approach to GDP: Y= C+ I + G + (Exports-Imports)

- Factor income approach to GDP: Y = Employee Compensation + Rent + Interest + Profit

The National Spending Approach:

- Economists have found it useful, especially for the analysis of short-run economic fluctuations, to split GDP into consumption, investment, government purchases, and exports minus imports, which is often shortened to Net Exports.

- Consumption: Private spending on finished goods and services. Most consumption spending is made by households, such as spending on cars and chickens.

- While economists think of education as an investment in “human capital,” the Bureau of Economic Analysis includes education as consumption spending alongside purchases of automobiles, smartphones, and televisions.

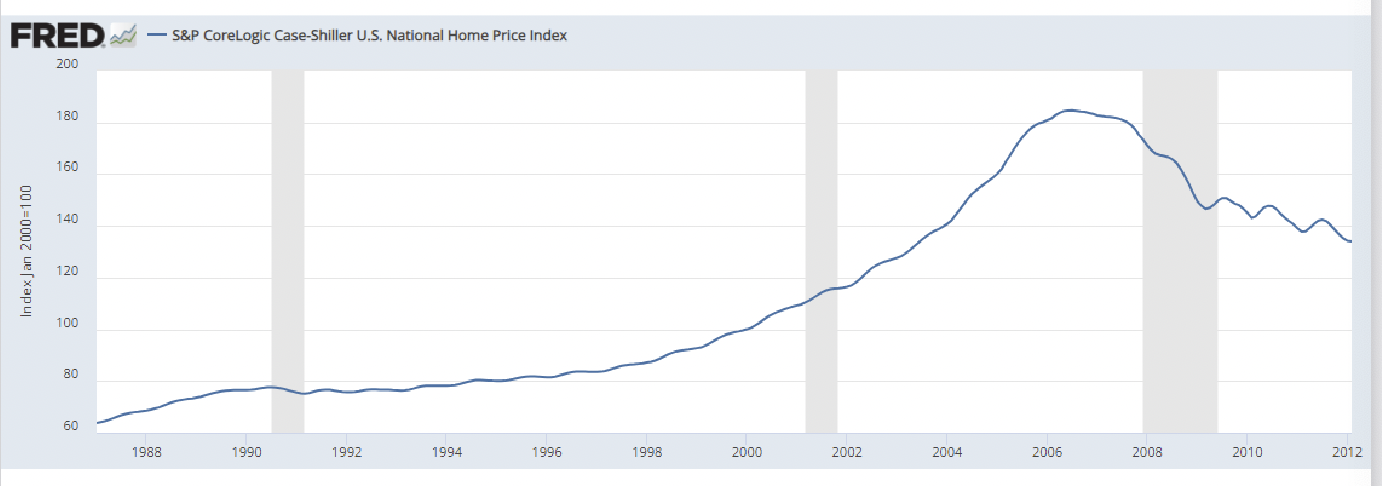

- Investment: The purchase of new capital goods; private spending on tools, plant, and equipment used to produce future output. Most investment spending is made by businesses but an important exception is that new home production is counted as investment.

- Government purchases: The third component of GDP. Government purchases is spending by all levels of government on finished goods and services not including transfers. A large part of what government does is transfer money from one citizen to another citizen; about 21% of the spending of the federal government, for example, is for Social Security payments.

- Net exports: Exports minus imports. When we are adding C+I+G, we are adding up all national spending but some of that spending was on imports, goods that were not produced domestically.

- Trade is not ultimately good or bad, but rather that Y=C+I+G+NX is an accounting identity that can’t by itself answer the question of business fluctuation.

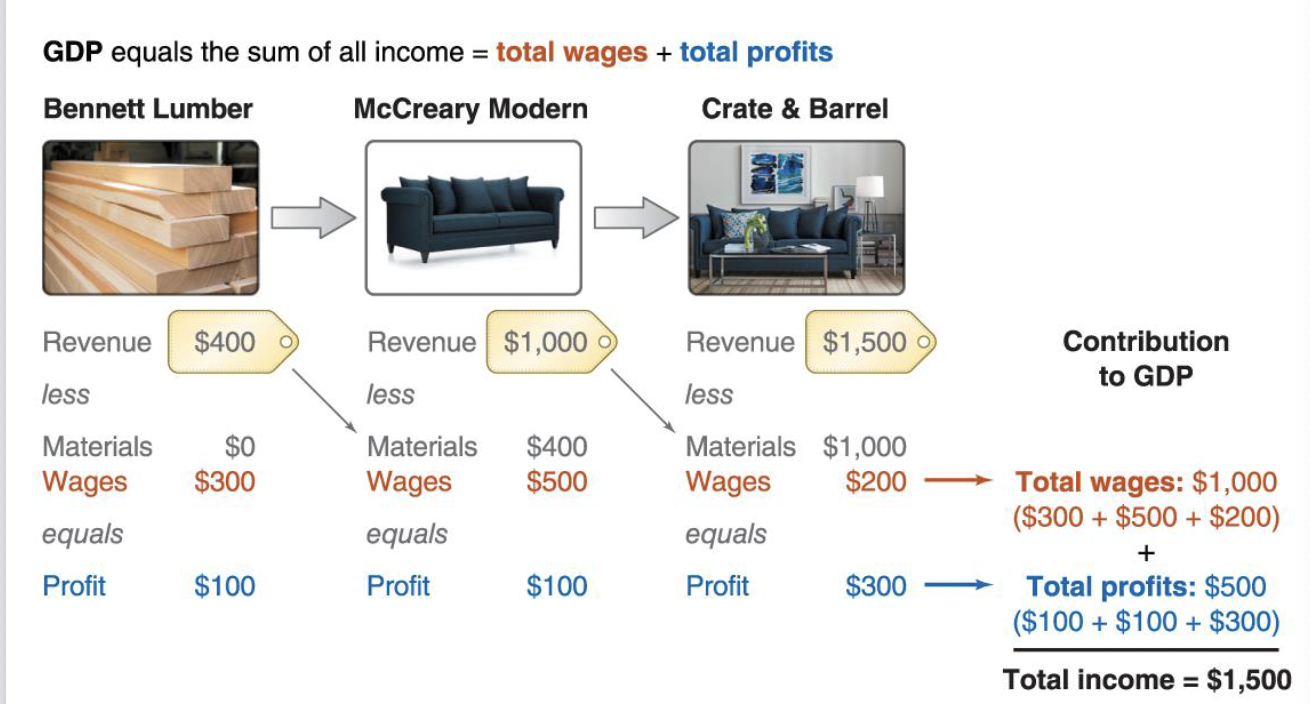

The Factor Income Approach:

- GDP can also be written as: Y= Employee Compensation + Rent + Interest + Profit

- When a consumer spends money, the money is received by workers (employee compensation = wages + benefits), landlords (rent), owners of capital (interest), and businesses (profit).

- Not every dollar spent on goods and services is a dollar received in income.

- Employee compensation (wages and other benefits) accounts for about 54% of GDP–more than most people expect and much larger than corporate profits, which are around 10% of GDP.

Problems with GDP as a Measure of Output and Welfare:

- GDP measures the market value of finished goods and services. But we do not know the market value of many goods and services nor do we know the market value of goods and service that are not bought and sold in markets.

- Nations with a great deal of illegal and off-the books activity are not as poor as they appear in the official GDP statistics.

- GDP does not count nonpriced production. Nonpriced production occurs when valuable goods and services are produced but no explicit monetary payment is made. The omission of nonpriced production introduces two biases into GDP statistics: biases over time and biases across nations.

- GDP Does not count bads-Environmental Costs: GDP adds up the market value of finished goods and services, but it does not subtract the value of bads. Pollution, for example, is a bad that is produced every year, but this bad is not counted in the GDP statistics (destruction of water aquifers, the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere, or the changing supplies of natural resources are also not counted. For ex, America has cleaner air and cleaner water than it did in 1960, but GDP statistics do not reflect this improvement.

- GDP does not count the health of nations: According to ecnomists Kevin Murphy and Robert Topel, ncreases in life expectancy are worth tens of trillions of dollars, however value of health is not included in GDP.

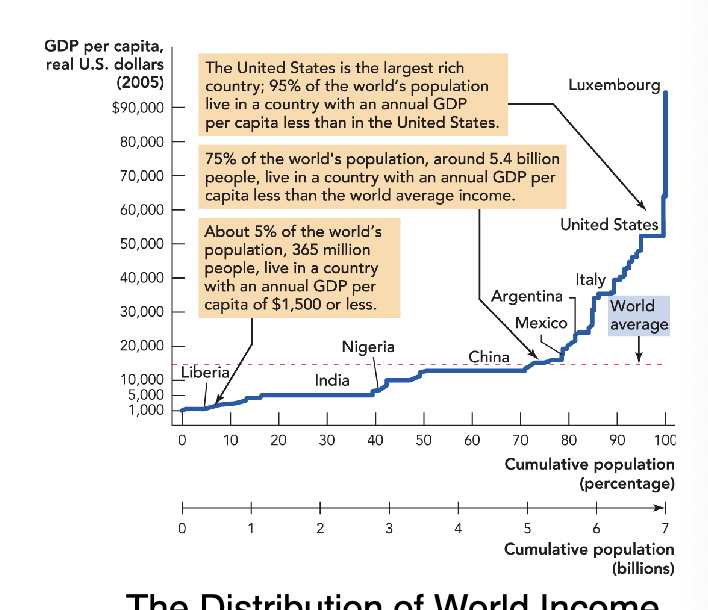

- GDP does not measure the distribution of income: GDP figures are useful but they will always be imperfect.

Takeaways:

- National spending identity: Y = C+I+G+NX, splits GDP according to different classes of income spending

- The factor income approach: Y = Employee compensation + Interest + Rent + Profit, splits GDP into different classes of income receiving.

- GDP per capita is a rough estimate of the standard of living in a nation. Real GDP is GDP per capita corrected for inflation by calculating GDP using the same set of prices in every year.

- Growth in real GDP per capita tells us roughly how the average person’s standard of living is changing over time.

- GDP and GDP per capita also do not tell us anything about how equally GDP is distributed.

- Economies of Scale: Economies of scale refers to the fact that as production is scaled up, that is, increased quantity, the average cost of producing a good decreases.

Unit 2 Notes:

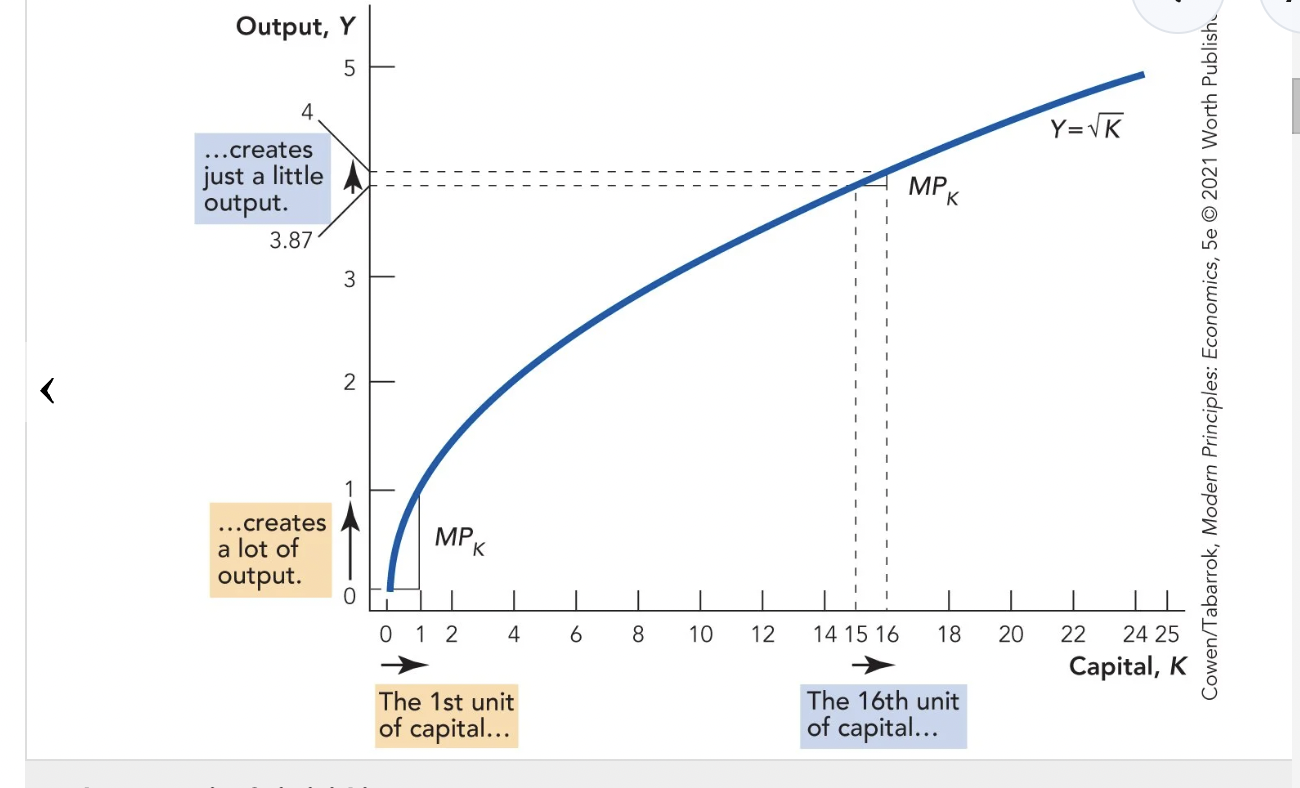

The law of diminishing returns

thus states that when one input is held constant, increases in the other inputs will begin to yield smaller and smaller increases in output.

February 5th-Chapter 6 Notes:

Introduction:

- Real GDP per capita: A rough measure of a country’s standard of living.

- Switzerland: $91,991.60 (2021)

- Italy: $35,657.50 (2021)

- Switzerland’s residents on average produce 2.6 times as many goods and services as Italy’s.

- Switzerland’s residents can afford 2.6x as much as Italy’s can

Origins of National Income Accounting:

William Petty (1623-1687)

- Hobbes and Empircism

- Down Survey

- Varbun Sapienti

- Political Arithmetick

- The article of the trade of commerce is more of a general piece

Simon Kuznets (1901-1985)

- Wesley Clair Mitchell and Institutionalism: His goal was not to just rely on theory, but rely on as many historical aspects as possible to apply to theory.

- NBER-tool of state trend, allows economists to use statistics reflecting how this will be the basis on how economists collect data. Most use his data or use his theories of collecting data. The origins of modern income accounting.

- “National Income, 1929-1932” (1934)

- National Income and Capital Formation, 1919-1935 (1937)

- National Product Since 1869 (1946)

- Nobel Prize (1971)

Kuznet’s National Income Accounting:

- Decides how much businesses and their owners end up receiving, salaries, withdrawals, how individual entrepreneurs and corporations have business savings or losses, etc.

- Gross Domestic Product: The market value of all finished goods and services produced within a country in a year. Each component is an important part of this definition:

- Market value

- An economy’s total output includes millions of different goods and services

- Some goods are more valuable than others, so we can’t just add up quantities.

- GDP uses market values to determine how much each good or service is worth and then sums the total.

- Of all

- As a comprehensive measure, GDP includes everything produced and sold in markets

- The output of an economy includes both goods and services

- Haircuts, medical care, and transportation are some examples of services

- Nonmarket goods and services are not included

- Finished goods and services

- Only finished goods and services sold to the final consumer are included (ex. A phone)

- Intermediate goods and services used to make another good or service are not included (ex. A silicon chip used to make a phone)

- If intermediate goods were counted, their value would be double-counted

- Counting the silicon chip in itself and as part of the phone would include that chip trice in GDP.

- However, machinery and equipment used to produce other goods are included in GDP

- Any good still on its way to its final transaction to the customer is an intermediate good.

- Produced

- GDP measures production, so it doesn’t count the resale of existing goods & services (ex. Sale of a used car)

- Second-hand sales change only the ownership of the product

- But the services of the used car dealer getting you in a carry today are new

- Within a country

- U.S. GDP measures what is collectively produced domestically (within the U.S.)

- This includes products made in the U.S. by foreign-owned businesses.

- U.S. GDP doesn’t include products made in foreign countries by American-owned businesses.

- In a year

- There needs to be a time frame for GDP

- A year is typically used, although measures are also reported quarterly.

GDP vs. GNP

- GDP: Total output, total spending amd total income in the economy have the same value, which is the economy’s GDP.

- Gross National Product (GNP): The market value of all finished goods and services produced by a country’s permanent residents, wherever they are located, within a year.

- U.S. GDP includes goods and services produced by labor and capitol located in the United States, regardless of the nationality of the worker or property owners.

- GNP is similar to GDP but measures what is produced by the labor and property supplied by U.S. permanent residents

- GNP-GDP = factor payments from abroad - factor payments to abroad

GDP vs. National Health:

- National wealth refers to the value of a nation’s entire stock of assets

- GDP tells us how much the nation produced in a year, not how much it has accumulated in its entire history.

- GDP is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), part of the Department of Commerce.

Using GDP:

- And cross-country comparisons

- U.S. $23.3 trillion (2021)

- China $17.7 trillion (2021)

- For measures of prosperity and growth, it is best to use GDP per capita–GDP divided by population

- U.S. $70,243 (2021)

- China $12,556 (2021)

Growth Rates:

- GDP growth rate– the percentage increase in GDP

- Growth rate of GDP for 2018 = [(GDP2018-GDP2017)/GDP2017] x 100

- Using actual numbers (in billions): [($20,580-$19,519)/ $19,519] x 100 = 5.4%

- (GDP 2-GDP1)/GDP1 x 100

GDP per capita growth rate:

- (GDP per capita for previous year-GDP per capita for present year x 100)/GDP per capita growth for previous year

- 0.201

Formulas:

GDP: Y=C+I+G+(Exports-Imports)

Factor Income Approach to GDP: Y= Employee Compensation+Rent+Interest+Profit

Productivity: GDP/workers

Productivity growth rate: (GDP year 2/workers year 2-gdp year 1/workers year 1)/gdpyear 1/workers year 1

Have you calculated productivity by dividing GDP by workers? Then use those numbers to find productivity growth.

February 7th Notes:

Using GDP:

- GDP facilitates cross-country comparisons

- U.S. $23.3 trillion (2021)

- China $17.7 trillion (2021)

- But for measures of prosperity, it is best to use GDP per capita–GDP divided by population

- U.S. $70,243 (2021)

- China $12,556 (2021)

- GDP facilitates itertemporal comparisons

- GDP growth rate-the percentage increase in GDP

- Growth rate of GDP for 2018= GDP2018-GDP2017/GDP2017 x 100

- Using actual numbers for example: $20,580-$19,519/$19,519 x 100 = 5.4%

Real and Nominal GDP:

- Nominal GDP: GDP measured in today’s prices

- Real GDP: GDP measured in constant prices

- The growth rate of quantity is: (QTY-QLY)/QLY

- The growth rate of price is: (PTY-PLY)/PLY

Calculating Nominal GDP and Growth rate:

- NGDP=RGDP+ Price Level

- Base Year: Year at which prices are held fixed (constant) in Real GDP calculation

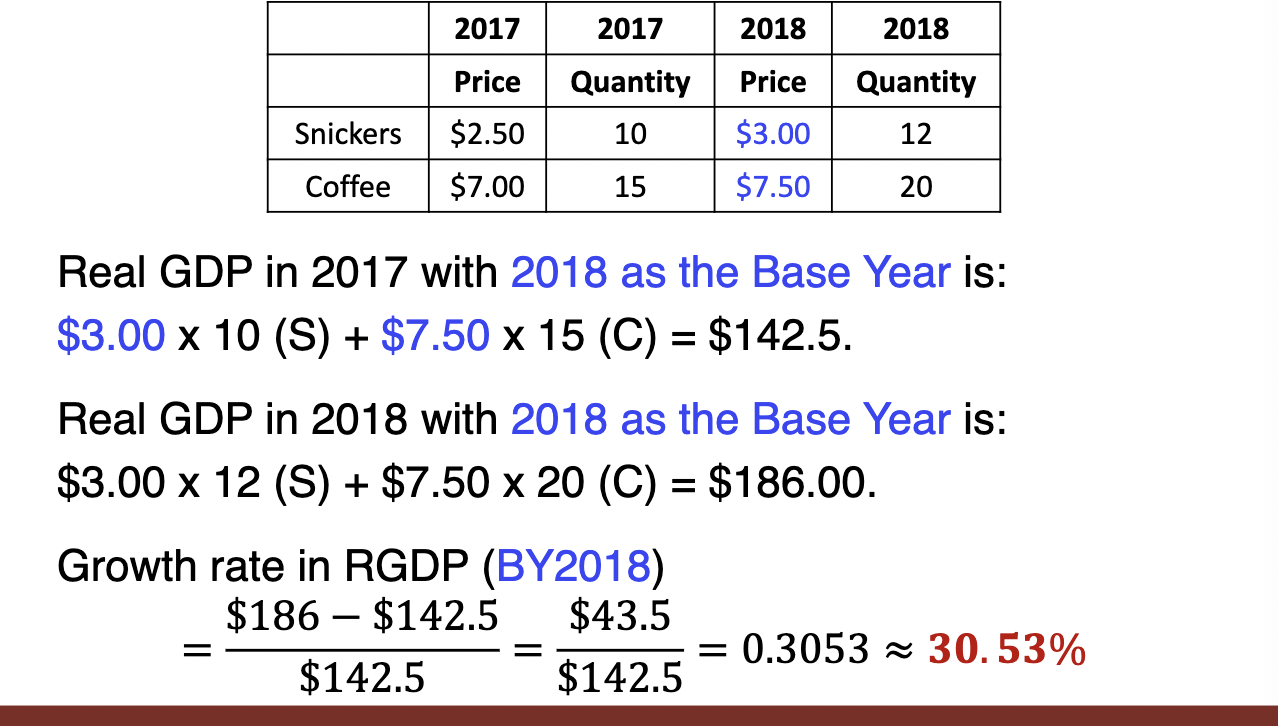

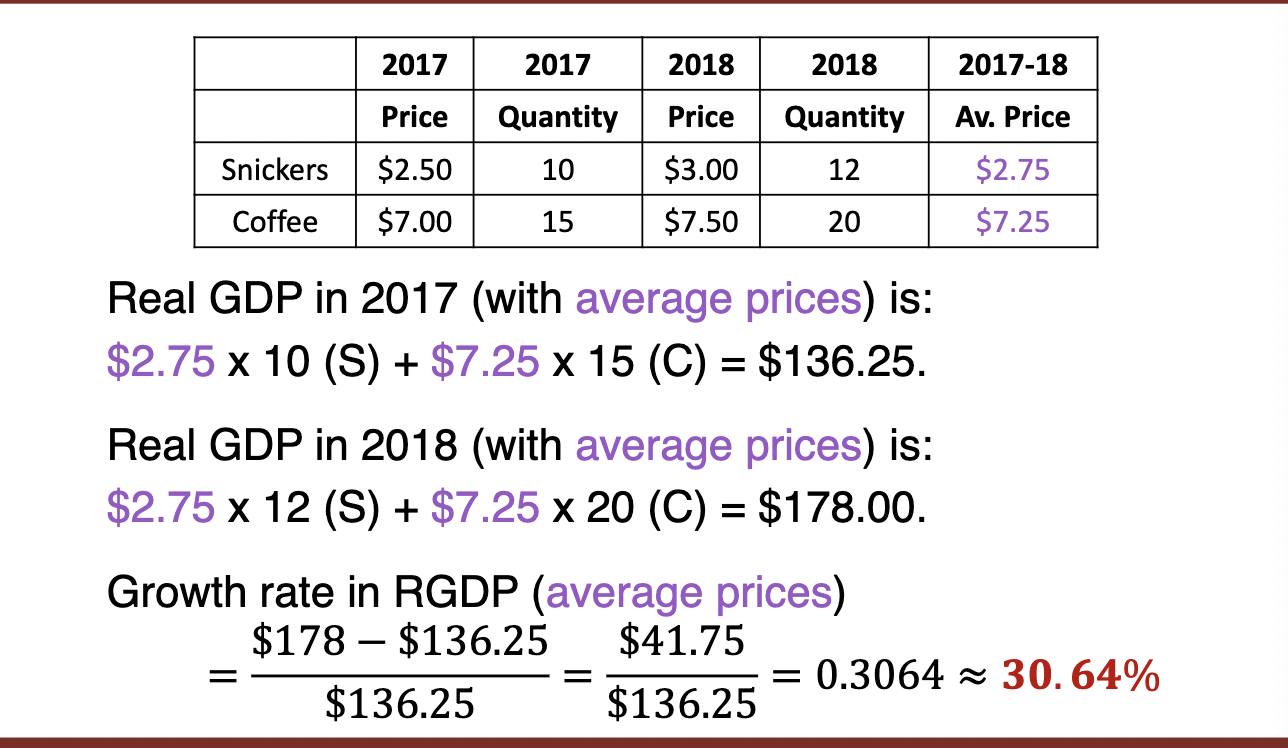

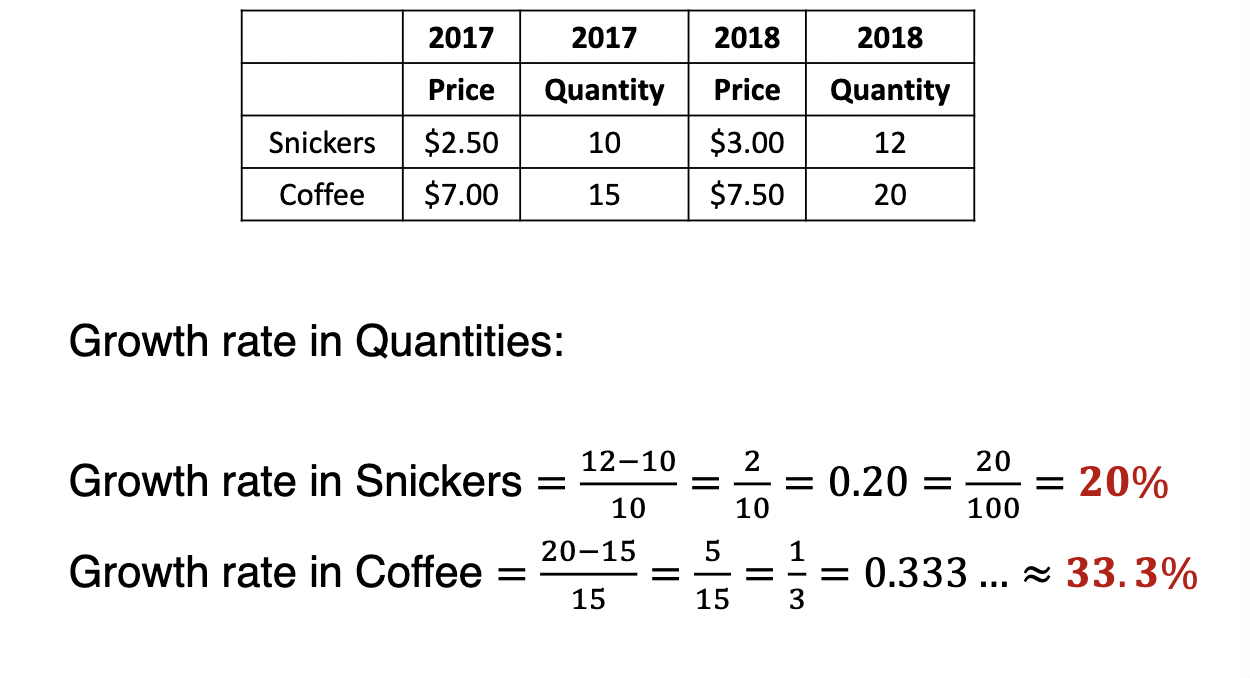

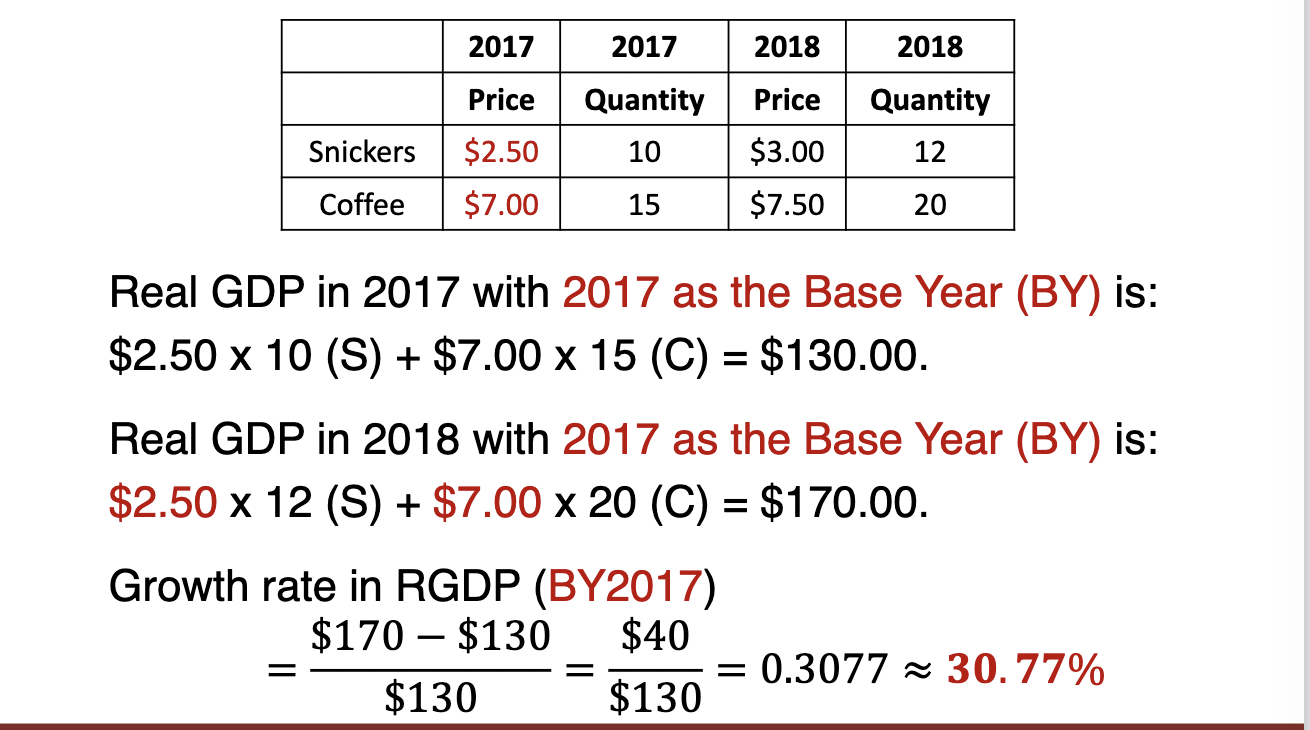

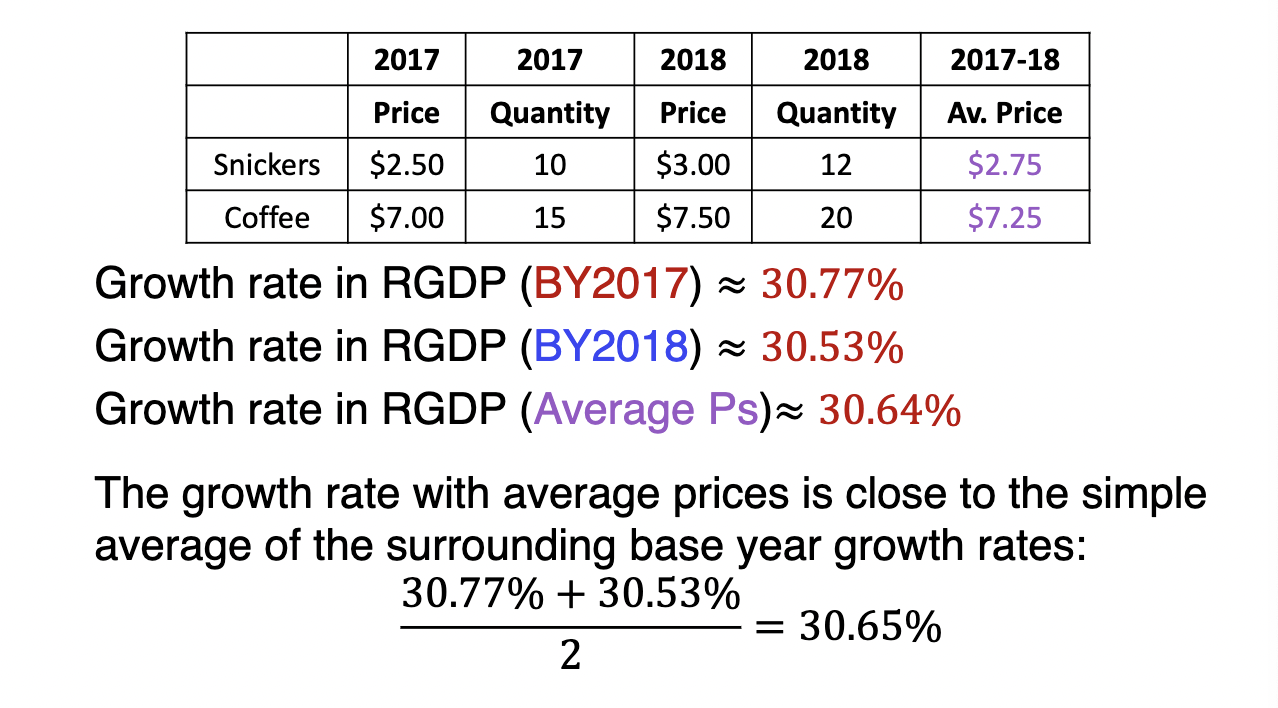

Example of Real GDP Growth Rates with Two Goods:

- Nominal GDP in 2017 is: $2.50 x 10(s) + $7.00 x 15(C) = $130.00

- Nominal GDP in 2018 is: $3.00 x 12 (S) + $7.50 x 20 © = $186.00

- Growth rate of NGDP = 186-130/130=43%

- But GR Snickers = 20%, GR Coffee = 33.33%

- Prices increased in addition to quantities increasing! Solution: hold prices constant → real GDP

Real GDP Growth per Capita:

- Real GDP helps control for price changes

- But growth in real GDP does not account for changes in population

- Growth in real GDP will thus overstate economic growth in countries with rapidly growing populations

- Thus growth in real GDP per capita is usually the best reflection of changing standards of living

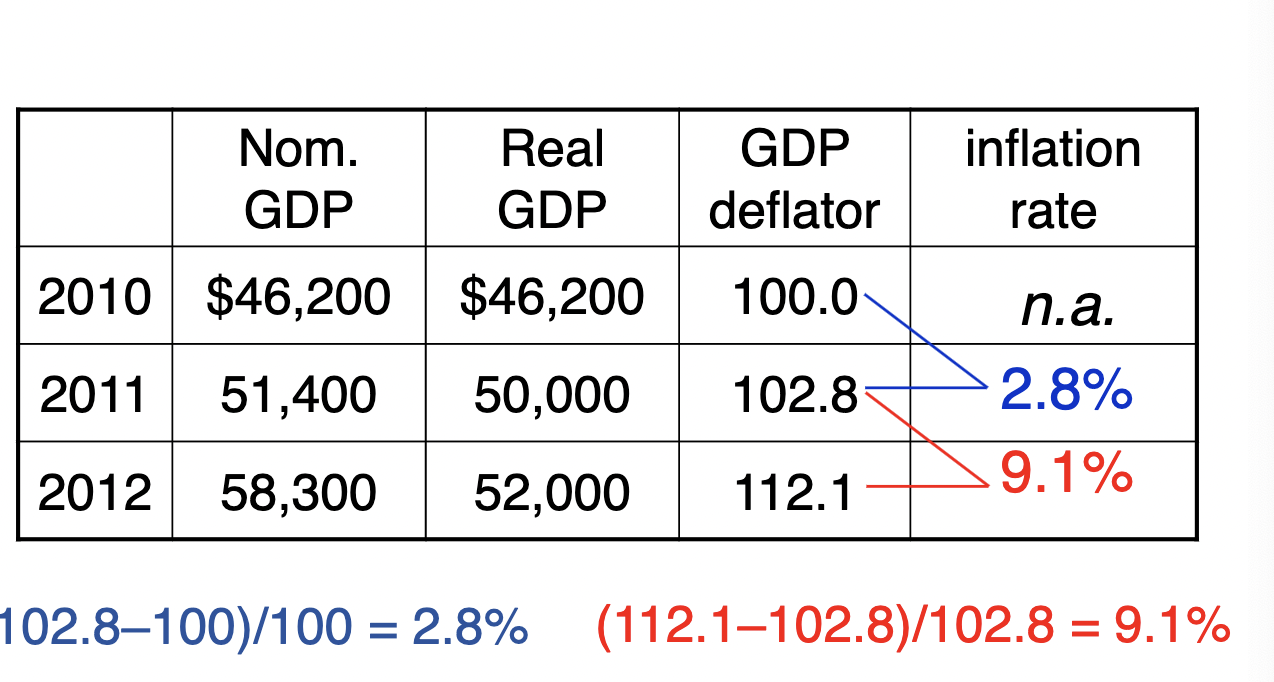

GDP Deflator:

- Since real GDP controls for price changes, we can use it and the fGDP to measure inflation (the change in overall price levels)

- The GDP deflator is a price index that can be used to measure inflation, calculated by finding the ration of nominal GDP to real GDP (nominal gdp/real gdp x 100)

Nominal GDP versus Real GDP:

- Nominal GDP measures the market value of GDP right now, based on current prices

- Real GDP controls for price changes to measure changes in the quantity of output produced

- Tral GDP per capita is the best measure of economic growth

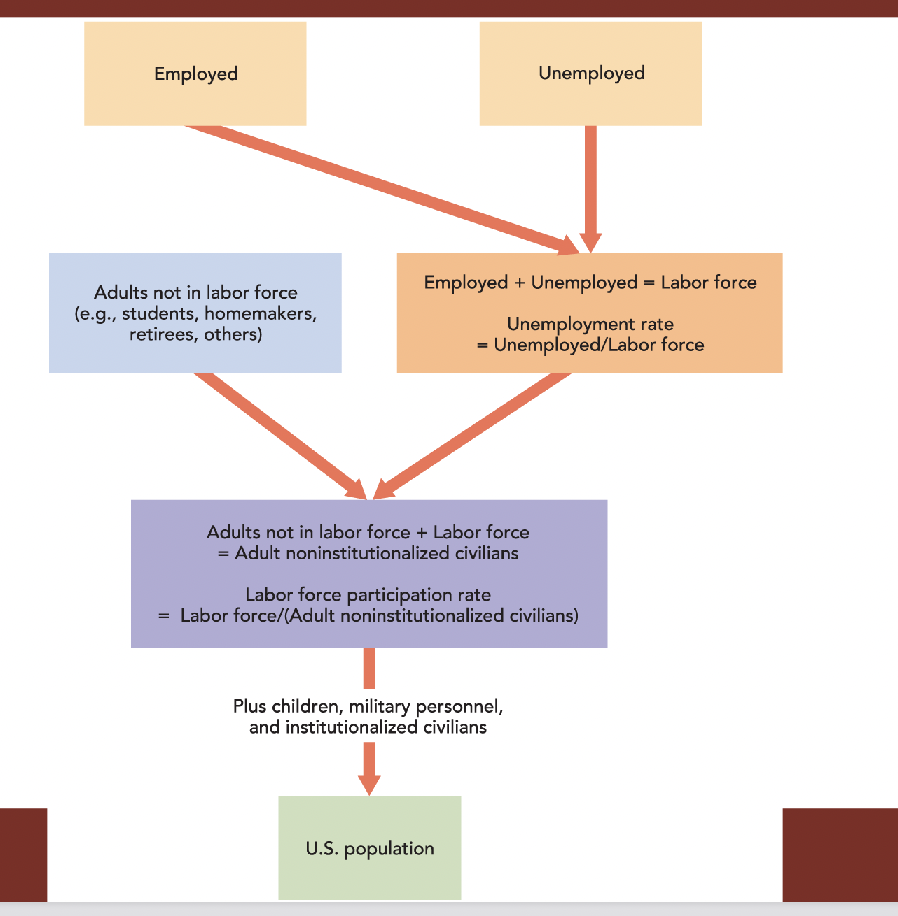

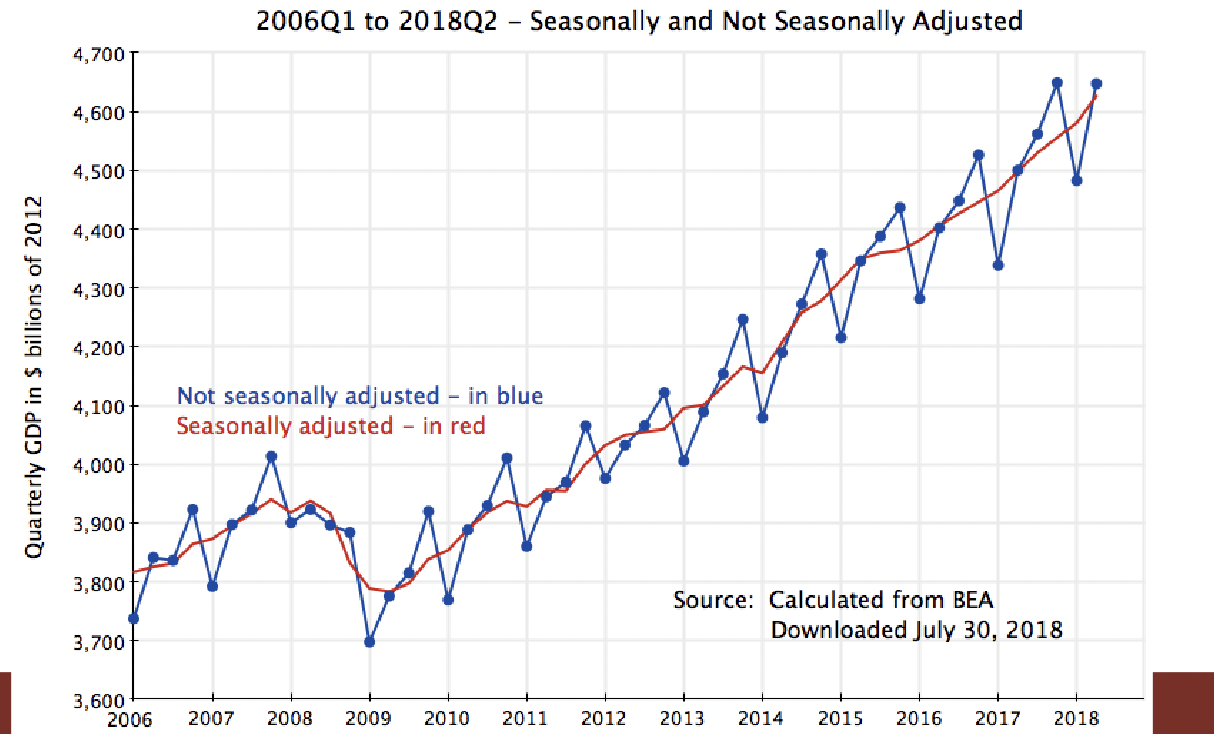

Short-Run Business Fluctuations:

- GDP is used to compare economic output across countries and over long periods

- GDP is also used to measure business fluctuations or business cycles (short-term movements in real GDP around its long-term trend)

- We call a significant, widespread decline in real GDP and employment a recession

- One popular rule of thumb defines a recession as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

- But the National Bueau of Economic Reasearch defines a recession as: A significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.

Chapter 7 Notes:

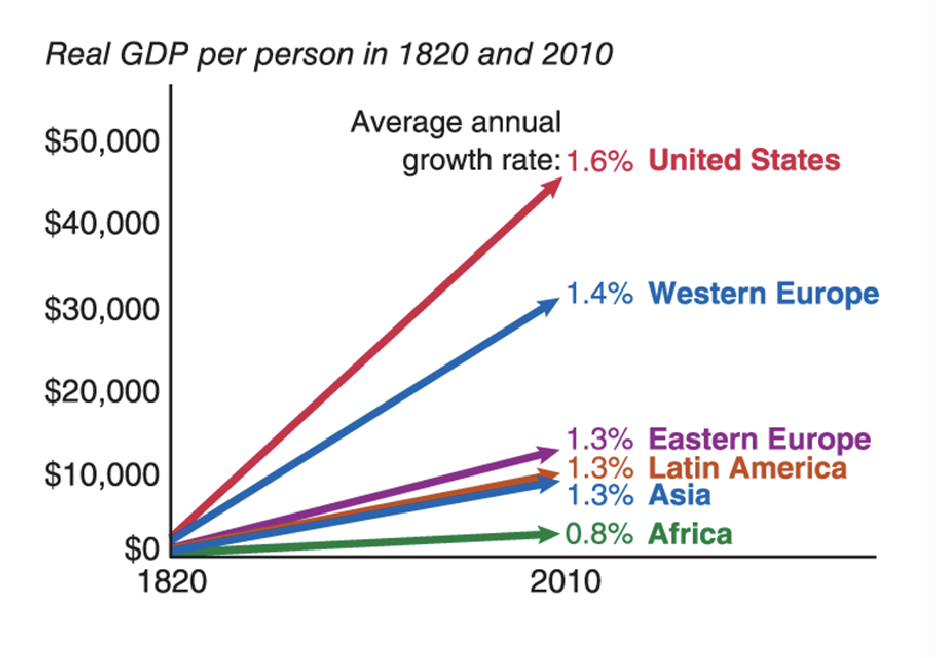

Key Facts About the Wealth of Nations and Economic Growth:

- GDP per Capita Varies Enormously Among Nations:

- 10% of the world’s population (772 million people) lived in a country with a GDP per capita of less than $2,900 (about the level in Bangladesh). 70% of the world’s population lived in a country with a GDP per capita equal or less than $12,472 (about the level in China), and 73% of the world’s population (5.2 billion people) lived in a country with a GDP per capita less than average. The US is the largest rich country in terms of GDP.

- Everyone Used to Be Poor:

- In different regions of the world, people were generally poor throughout time. From 1-2000 AD, in the year 1, the GDP per capita was about $700-$1,000. GDP per capita was about the same in year 1 as it would be 1,000 years later, and 1,000 years earlier. For most of human history, there was no long-run growth in real per capita GDP.

- In the nineteenth century some parts of the world began to grow at a rate unprecedented in human history.

A Primer on Growth rates:

- A growth rate is the percentage change in a variable over a given period, such as a year. When we refer to economic growth, we mean the growth rate of real per capita GDP.

- Even slow growth, if sustained over many years, produces large differences in real GDP per capita.

- Ex: If the annual growth rate of real GDP per capita is 2%, how long will it take for real per capita GDP to double from $40,000 to $80,000? Growth builds on top of growth, which is called compounding or exponential growth. To find this, you would use the rule of 70, which is doubling time=70/x years.

- At a growth rate of 2%, GDP per capita will double every 35 years (70/2=35)

- There are Growth Miracles and Growth Disasters:

- The U.S. is one of the wealthiest countries in they world because it has grown slowly but relatively consistently for more than 200 years. For example, after WW2 Japan was one of the poorest countries in the world. However, from 1950-1970, Japan grew at a rate of 8.5% per year (at that rate GDP per capita doubles in 8 years), and today Japan is one of the richest countries in the world.

- Growth disasters are also possible. For example, Nigeria has barely grown since 1950 and was poorer in 2005 than in 1974 due to high oil prices bumping up its per capita GDP. Argentina was one of the richest countries in the world in 1900 with a GDP 75% that of the US. But, by 1950, Argentina’s per capita GDP had fallen to half of the US, and by 2000 it was less than a third of that of the United States.

Summarizing the Facts:

- Most of the world is poor and more than 1 billion people live on incomes of less than $3 per day. But for most of human history, people were poor and there was no economic growth.

- Economic growth has quickly transformed the world, and has raised the standard of living of most people in developed nations many times above the historical norm. Growth miracles tell us that it doesn’t take 250 years to reach the level of wealth of the U.S.-- South Korea was as poor as Nigeria in 1950, but today has a per capita GDP not far behind Germany or the United Kingdom.

- Growth disasters tell us that economic growth is not automatic either, there are several causes that go into growth miracles and disasters.

Understanding the Wealth of Nations:

The Factors of Production-

- The most immediate cause of the wealth of nations is countries with a high GDP per capita have a lot of physical and human capital per worker and that capital is organized using the best tecnological knowledge to ne highly productive. Physical capital, human capital, and technological knowledge are called factors of production.

- Physical Capital: The stock of tools including machines, structures, and equipments. Some examples are pencils, desks, computers, hammers, shovels, tractors, cell phones, factories, roads, and bridges. Farming is an example of capital: They dig, seed, cut, and harvest using hard labor and simple tools like hoes and ploes. In the US, farmers use a lot more capital–tractors, tricks, combines, and harvesters. The typical worker in the U.S. works with more than $100,000 worth of capital.

- There is also a high tech nature of farming. A tractor’s location is combined with data from other satellites and land-based sensors to adjust the amount of seed, fertilizer, and water to be added to the land. Human capital is tools of the mind; the productive knowledge and skills that workers acquire through education, training, and experience. It is not something we are born with–it’s produced by an investment of time and other resources in education, training, and experience. For example, with farmers, its the human capital that enables them to take advantage of tools like GPS receivers and is why U.S. farmers are more productive (U.S. citizens typically have about 12 years of schooling).

- Technological Knowledge: Knowledge about how the world works that is used to produce goods and services. Includes the genetics, chemistry, and physics that form the basis of the techniques used in modern agriculture. Technological knowledge is increased with research and development, which is potentially boundless. We can learn more and more about how the world works even if human capital remains relatively constant.

- Organization: Human capital, physical capital, and technological knowledge must be organized to produce valuable goods and services.

Incentives and Institutions:

- One example of comparison is North Korea and South Korea. The GDP of South Korea is nearly 20 times higher than North Korea. South Korea has more physical and human capital than North Korea because they have more incentives. In South Korea a worker earns more money if he provides goods and services of value to consumers or if she invents new ideas for more efficient production. In North Korea, workers are rewarded just for being loyal to the ruling Communist Party.

- South Korea uses markets to organize its production much more than North Korea, so they are able to take advantage of all the efficiency properties of markets.

- Incentives matter and good institutions align self-interest with the social interest

- Countries with a high GDP per capita have institutions that make it in people’s self-interest to invest in physical capital, human capital, and technological knowledge and to efficiently organize these resources for production.

Institutions:

- Institutions are the “rules of the game” that structure economic incentives. They include laws and regulations but also customs, practices, organizations, and social mores–institutions are the “rules of the game” that shape human interaction and structure economic incentives within a society.

- Key Institutions include:

- Property rights

- Honest government

- Political stability

- A dependable legal system

- Competitive and open markets

- Institutions create appropriate incentives, incentives that align self-interest with the social interest.

Property Rights:

- Communal property meant that the incentives to invest in the land and to work hard were low.

- There is an incentive not to work and to free ride on the work of others. In the “Great Leap Forward,” the incentive to free ride was made even stronger when communes were increased to 5,000 families. If everyone free rides, the commune will starve. Communal property in agricultural land did not align a farmer’s self-interest with the social interest.

- The Great Leap Foward was essentially a great leap backward because agricultural land was less productive in 1978 than it had been in 1949 when the Communists took over. The farmers agreed to divide the land, which violated governmental policy. The change from collective property rights to something closer to private property rights had an immediate effect: investment, work effort, and productivity increased.

- From 1978-1983 in China, food production increased by nearly 50% and 170 million people were lifted above the World Bank’s lowest poverty line. Property rights in land greatly increased China’s agricultural production. China opened up to foreign investment. Property rights are also important for encouraging technological innovation.

Honest Government:

- Corruption is like a heavy tax that bleeds resources away from productive entrepreneurs. Resources “invested” in bribing politicans and bureaucrats cannot be invested in machinery and equipment, this reducing productivity.

- An honest government is one that spends taxpayer funds on public goods like education, infrastructure, and public health.

- Countries that are more corrupt have much lower per capita GDP.

Political Stability:

- Investors have more to fear than government expropriation.

- Liberia, for example, has had conflict for the past 40 years. Before the election in 2006 of President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, it had been 35 years since a Liberian president assumed office by means other than bloodshed.

- In many nations, civil war, military dictatorship, and anarchy have destroyed the institutions necessary for economic growth.

A Dependable Legal System:

- A good legal system facilitates contracts and protects private parties from expropriating one another. In the U.S. for example, it takes 17 procedures and 300 days to collect on a debt. In India, it takes 56 procedures and 1,240 days to do the same thing. This is why it’s relatively difficult for people living in India to borrow money in the first place. Lenders know how hard it is to get their money back.

Competitive and Open Markets:

- The factors of production must not only be produced–they must also be organized.

- The failure to organize capital efficiently has a huge effect on the wealth of nations.

- Half of the differences in per capita income across countries are explained by differences in the amount of physical and human capital.

- Ex: If India used its physical and human capital as efficiently as the U.S. uses its capital, India would be four times richer than it is today. Indian shirts are usually made by habnd in small shops with tailors who design, measure and sow. However, if they were mass manufactured, Indian shirts could be cheaper to make. In the past, in an effort to protect small firms, India prohibited investment in shirt factories from exceeding about $200,000. This meant that Indian shirt manufacturers could not take advantage of economies of scale.

- Economies of Scale: The decrease in the average cost of production that often occurs as the total quantity of production increases.

- In the U.S., it takes about 4 days to start a business, but in India it takes 26, and in Haiti it takes 97 days. Thus, even before a business is begun, an Indian/Haitain entrepreneur must invest extensively in dealing with bureaucracies.

The Ultimate Causes of the Wealth of Nations:

- Institions have a large effect on increasing and organizing the factors of production, and institutions thus have a large effect on economic growth

- Simple natural resources like oil and diamonds are usually good to have but in rich, developed countries, physical and human capital are typically mnuch more important.

- Free trade is not just a matter of policy or choice–it also depends on natural conditions.

- Growth miracle example: The industrial Revolution. This was the first time that human living standards climbed noticeably above the subsistence and stayed there for a long period.

- More wealth in the revolution meant more people could devote their lives to science, invention, and turning new ideas into practical commercial developments. This in turn led to new wealth and then again to more applied science.

- Understanding institutions, where they come from, and how they can be changed is thus a key research question in economics.

Takeaways:

- Today GDP per capita is more than 50 times higher in the riches countries than the poorest

- Poor countries can catch up to rich countries in a surprisingly short period through growth “miracles”.

- What makes a country rich: Countries with a high GDP per capita have lots of physical and human capital per worker, and that capital is organized using the best technological knowledge to be highly productive.

- Countries with a high GDP per capita have institutions that encourage investment in physical capital, human capital, technological innovation, and the efficienty organization of resources.

- Most powerful institutions for increasing economic growth include: property rights, honest government, political stability, a dependable legal system, and competitive and open markets.

February 9th Notes:

Nominal GDP vs. Real GDP:

- Nominal GDP is calculated using prices at the time of the sale

- GDP in 2018 is calculated using 2018 prices.

- GDP in 2017 is calculated using 2017 prices.

- This creates problems when comparing GDP over time.

- We can’t tell if an increase in nominal GDP was due to greater production or increased prices

- Increases in production, not increases in prices, improve the standard of living, so we control for changes in prices with real GDP measures.

Example:

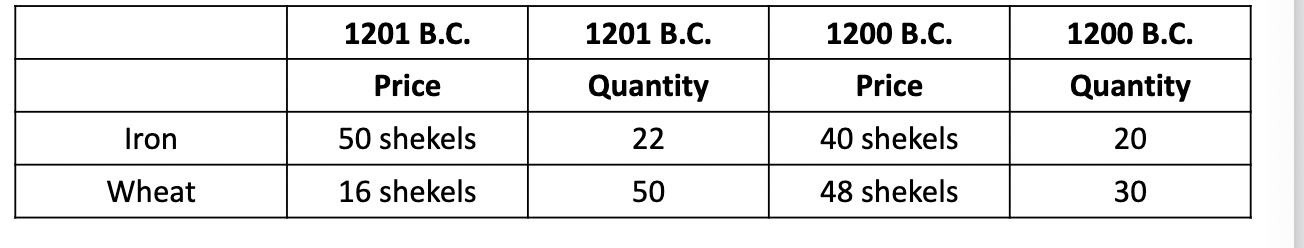

Nominal GDP in 1201 B.C. is:

50 shekels x 22 (I)+16 shekels x 50 (W) = 1,900 shekels

Nominal GDP in 1200 B.C. is:

40 shekels x 20 (I) + 32 shekels x 30 (W) = 2,240 shekels

Growth in NGDP =2240-1900/1900Real GDP:x

GDP Deflator:

- The GDP deflator (the ration of nominal GDP to real GDP) is a price index that can be used to measure inflation: GDP deflator = nominal gdp/real gdp x 100

- If 2016 nominal GDP + $18.57 trillion, and 2016 real GDP (in 2009 dollars) = $16.66 trillion, GDP deflator = 18.57 trillion/16.66 trillion x 100 = 111.46

- This tells us that 2016 prices were 11.46% higher (111.46-100) than 2009 prices.

The Many Ways of Splitting GDP:

- National spending approach: Add up the components of spending. Y = C + I + G + (Exports - Imports)

- Factor income approach: Add up the income generated by producing goods and services. Y = Employee Compensation + Rent + Interest + Profit

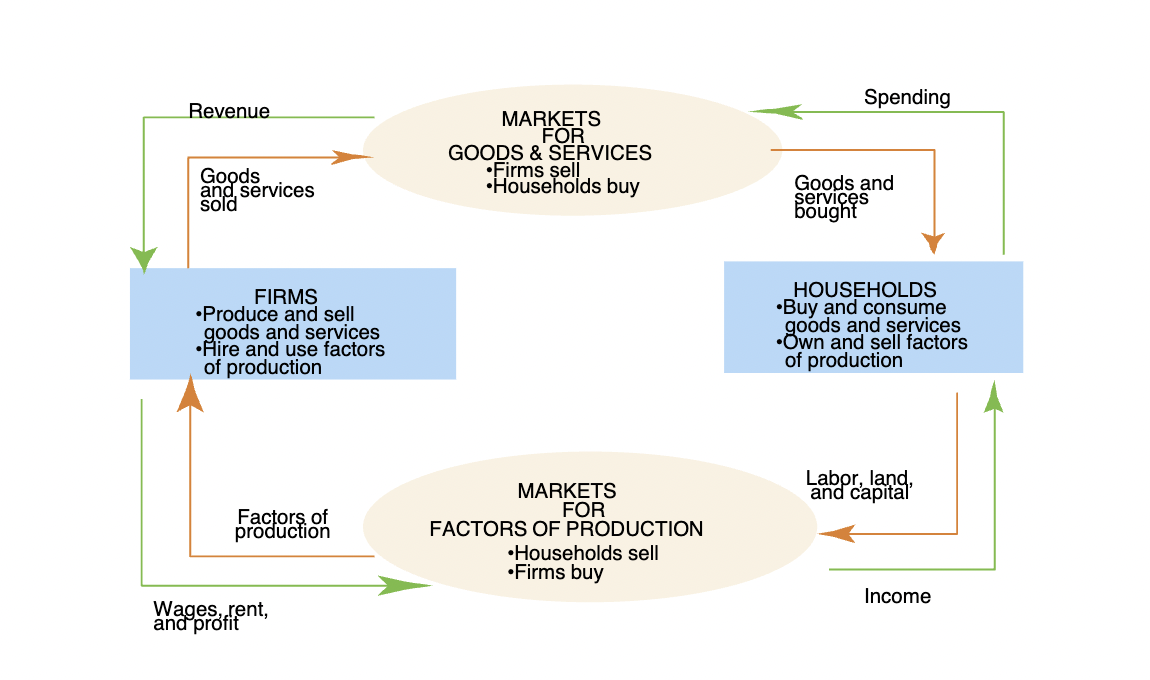

The Circular Flow Model:

- Illustrates the interdependence of the macroeconomy

- Provides a conceptual framework for analyzing macroeconomic interdependence.

An output that’s produced gets sold at some market price → The market value of total output must be equal to total spending.

Every dollar that someone spends is a dollar of income for someone else → Total spending must be equal to total income.

GDP as Total Spending:

- GDP is the sum of consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports.

- Y = C + I + G + NX

Consumption:

- The value of all private spending on finished goods and services

- Includes:

- Durable goods

Last a long time

E.g., cars, home appliances

- Nondurable goods

Last a short time

E.g., food, clothing

- Services

Intangible items purchased by consumers e.g., dry cleaning, air travel

Investment:

- Private spending on capital–private spending on tools, plant, and equipment used to produce future output.

- Includes:

- Business fixed investment

Spending on plant, equipment, and intellectual property

- Residential fixed investment

Spending by customers and landlords on housing units

- Inventory investment

The change in the value of all firm’s inventories

- Consumption includes products made that year/that time

Investment vs. Capital:

- Investment is spending on new capital.

- Example (assuming no depreciation):

- 1/1/2021: Economy has $10 trillion worth of capital

- During 2021: Investment = $2 trillion

- 1/1/2022: Economy will have $12 trillion worth of capital.

Government Spending:

- G includes spending by all levels of government on finished goods and services (including investments)

- G excludes transfer payments like social security checks, unemployment insurance payments, etc.

- These transfer payments do NOT represent spending on goods and services.

Net Exports (NX):

- NX = exports - imports

- Exports: The value of goods and services sold to other countries