Chapter 5 - The Gap

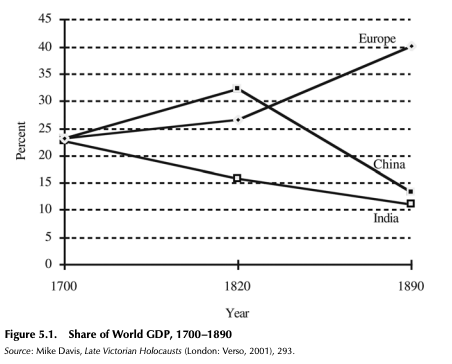

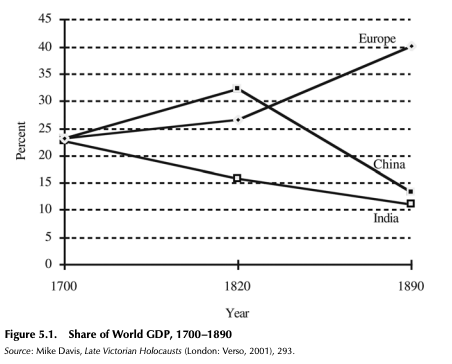

China, India, and Europe were largely equivalent in terms of economic development, standard of living, and life expectancy in the eighteenth century.

India, China, and Europe all claimed almost the same amount of the world's total gross domestic product (GDP).

Thus, in 1700, just three regions of the world accounted for 70% of global economic activity.

In 1750, China produced around 33% of all manufactured items in the globe, with India and Europe each contributing approximately 23%, totalling nearly 80% of global industrial production.

By 1800, the narrative is similar, albeit India's contribution begins.

By 1900, India accounted for only 2% of global industrial production, with China accounting for 7%, while Europe alone claimed 60% and the US 20%, for a total of 80%.

In the eighteenth century, India and China accounted for slightly more than half of the world's wealth; by 1900, they had become among the least industrialized and impoverished.

Their portions of global GDP did not decline as much as their shares of global industrial output, owing to their populations' sustained growth.

China's population surpassed that of both India and Europe between 1750 and 1850.

Figures 5.1 as shown in the impact attached above depict the formation of a vast and expanding divide between the West and the rest of the globe throughout the nineteenth century, as shown by India and China.

"To explain this divide, which was to widen through time," the great historian Fernand Braudel once stated, "is to solve the central challenge of contemporary global history."

Braudel himself was cautious about his own capacity to explain "the gap," acknowledging that when he wrote (in the late 1970s), more was known about European history than about India, China, or the rest of what has come to be regarded as the "underdeveloped" or "third" world.

Braudel was expressing his unhappiness with the many Eurocentric interpretations of "the gap" discussed in the preceding chapter.

He argued that theories that focused solely on the establishment and "rationalization" of a market economy in Europe were overly simple.

Indeed, as discussed in the last chapter, by the seventeenth century, China had a fairly well-developed market economy, but it was on the losing end of the widening disparity.

This chapter investigates why, over the nineteenth century, not just China and India, but also most of the rest of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, became progressively destitute in comparison to Europe and the United States.

In this chapter, we will look at how opium, weapons, and El Nino affect the environment.

Japan

Unlike Russia, Japan lacked many of the natural resources required for an industrial economy, particularly coal and iron ore.

Furthermore, it was still implementing a policy of "closed country" set two centuries earlier in the mid-1800s.

When US Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay in 1853, insisting that Japan open itself.

lf up to "regular" foreign business ("or else..."), Japan's officials were taken aback.

Knowing what had occurred to China at the hands of the British during the Opium War, Japan's authorities opted to negotiate an opening to the West, which resulted in increased commerce and interaction between Japanese and Westerners, but also in the fall of the old regime in 1868.

After some fits and starts, the new regime, known as the Meiji era after the reign title of the new (and very young) emperor Meiji set about dismantling the old feudal system and establishing a strong, centralized state that took on the task of industrializing Japan when private capital failed to take up the challenge.

However, with scant natural resources and tariffs controlled by treaties enforced by the US, Japan's industrialisation pursued an unusual course.

Having to first export in order to purchase industrial raw materials, Japan resorted to its silk industry, standardizing and mechanizing as much as possible in order to sell on the global market, eroding the Chinese and French market share.

This method was quite profitable. Its force was powerful enough to beat China in an 1894-1895 war and then Russia a decade later.

Recognizing Japan's military might, the British signed a military treaty with it in 1902, and the Western countries repudiated the unequal treaties that had limited Japan's capacity to manage its own tariffs in 1911.

By 1910, Japan had the industrial capability and technological know-how to build the Satsuma, the world's biggest warship.

Even while China and India continued to weaken in relation to the West, Japan's industrialization by 1900 signaled that the West would not continue to rule the globe through a monopoly of industrial production, but that past patterns of Asian vigor would begin to emerge.

By 1900, Europe and the United States accounted for 80% of global industrial output, with Japan accounting for 10%, China accounting for 7%, and India accounting for 2%, totalling 99 percent of worldwide industrial production.

Thus, between 1800 and 1900, there was a significant turnaround, with Europe and the United States occupying the place previously occupied by India and China.

Part of the enormous disparity between the richest and poorest portions of our globe may therefore be explained by industrialization and the escape of some areas of the world—Europe, the United States, and Japan—from the biological old regime's restraints.

Of course, it is more accurate to argue that industrial output emanated from certain regions rather than the entire country.

Chapter 5 - The Gap

China, India, and Europe were largely equivalent in terms of economic development, standard of living, and life expectancy in the eighteenth century.

India, China, and Europe all claimed almost the same amount of the world's total gross domestic product (GDP).

Thus, in 1700, just three regions of the world accounted for 70% of global economic activity.

In 1750, China produced around 33% of all manufactured items in the globe, with India and Europe each contributing approximately 23%, totalling nearly 80% of global industrial production.

By 1800, the narrative is similar, albeit India's contribution begins.

By 1900, India accounted for only 2% of global industrial production, with China accounting for 7%, while Europe alone claimed 60% and the US 20%, for a total of 80%.

In the eighteenth century, India and China accounted for slightly more than half of the world's wealth; by 1900, they had become among the least industrialized and impoverished.

Their portions of global GDP did not decline as much as their shares of global industrial output, owing to their populations' sustained growth.

China's population surpassed that of both India and Europe between 1750 and 1850.

Figures 5.1 as shown in the impact attached above depict the formation of a vast and expanding divide between the West and the rest of the globe throughout the nineteenth century, as shown by India and China.

"To explain this divide, which was to widen through time," the great historian Fernand Braudel once stated, "is to solve the central challenge of contemporary global history."

Braudel himself was cautious about his own capacity to explain "the gap," acknowledging that when he wrote (in the late 1970s), more was known about European history than about India, China, or the rest of what has come to be regarded as the "underdeveloped" or "third" world.

Braudel was expressing his unhappiness with the many Eurocentric interpretations of "the gap" discussed in the preceding chapter.

He argued that theories that focused solely on the establishment and "rationalization" of a market economy in Europe were overly simple.

Indeed, as discussed in the last chapter, by the seventeenth century, China had a fairly well-developed market economy, but it was on the losing end of the widening disparity.

This chapter investigates why, over the nineteenth century, not just China and India, but also most of the rest of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, became progressively destitute in comparison to Europe and the United States.

In this chapter, we will look at how opium, weapons, and El Nino affect the environment.

Japan

Unlike Russia, Japan lacked many of the natural resources required for an industrial economy, particularly coal and iron ore.

Furthermore, it was still implementing a policy of "closed country" set two centuries earlier in the mid-1800s.

When US Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay in 1853, insisting that Japan open itself.

lf up to "regular" foreign business ("or else..."), Japan's officials were taken aback.

Knowing what had occurred to China at the hands of the British during the Opium War, Japan's authorities opted to negotiate an opening to the West, which resulted in increased commerce and interaction between Japanese and Westerners, but also in the fall of the old regime in 1868.

After some fits and starts, the new regime, known as the Meiji era after the reign title of the new (and very young) emperor Meiji set about dismantling the old feudal system and establishing a strong, centralized state that took on the task of industrializing Japan when private capital failed to take up the challenge.

However, with scant natural resources and tariffs controlled by treaties enforced by the US, Japan's industrialisation pursued an unusual course.

Having to first export in order to purchase industrial raw materials, Japan resorted to its silk industry, standardizing and mechanizing as much as possible in order to sell on the global market, eroding the Chinese and French market share.

This method was quite profitable. Its force was powerful enough to beat China in an 1894-1895 war and then Russia a decade later.

Recognizing Japan's military might, the British signed a military treaty with it in 1902, and the Western countries repudiated the unequal treaties that had limited Japan's capacity to manage its own tariffs in 1911.

By 1910, Japan had the industrial capability and technological know-how to build the Satsuma, the world's biggest warship.

Even while China and India continued to weaken in relation to the West, Japan's industrialization by 1900 signaled that the West would not continue to rule the globe through a monopoly of industrial production, but that past patterns of Asian vigor would begin to emerge.

By 1900, Europe and the United States accounted for 80% of global industrial output, with Japan accounting for 10%, China accounting for 7%, and India accounting for 2%, totalling 99 percent of worldwide industrial production.

Thus, between 1800 and 1900, there was a significant turnaround, with Europe and the United States occupying the place previously occupied by India and China.

Part of the enormous disparity between the richest and poorest portions of our globe may therefore be explained by industrialization and the escape of some areas of the world—Europe, the United States, and Japan—from the biological old regime's restraints.

Of course, it is more accurate to argue that industrial output emanated from certain regions rather than the entire country.

Knowt

Knowt