Translation: RNA to Protein

FROM RNA TO PROTEIN

By the end of the 1950s, biologists demonstrated that the information encoded in DNA is copied first into RNA and then into protein. The debate shifted to the “coding problem”: How is the information in a linear sequence of nucleotides in an RNA molecule translated into the linear sequence of amino acids in a protein? This question intrigued scientists from various disciplines, including physics, mathematics, and chemistry. The human brain, as a product of evolution, was finally able to solve this cryptogram established by nature after over 3 billion years of evolution. Scientists have revealed, in atomic detail, the precise workings of the machinery by which cells read this code.

An mRNA Sequence Is Decoded in Sets of Three Nucleotides

Transcription: DNA and RNA are chemically and structurally similar, allowing DNA to act as a direct template for the synthesis of RNA through complementary base-pairing. This process of transcription is analogous to converting a handwritten message into a typewritten text without changing the language or form.

Translation: The conversion of information from RNA into protein translates the information into another language using different symbols. There are only 4 different nucleotides in mRNA but 20 different types of amino acids in proteins. Therefore, a direct one-to-one correspondence between a nucleotide in RNA and an amino acid in protein is not sufficient. The set of rules by which the nucleotide sequence of a gene is translated into the amino acid sequence of a protein via an intermediary mRNA is known as the genetic code.

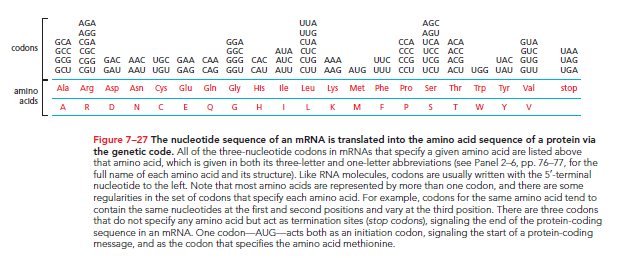

In 1961, it was discovered that the nucleotide sequence in mRNA is read in groups of three called codons. Since RNA is composed of 4 different nucleotides, there are 4 × 4 × 4 = 64 possible combinations of nucleotide triplets like AAA, AUA, AUG, etc. However, only 20 different amino acids are commonly found in proteins, indicating that some codon triplets are either unused or redundant, with some amino acids specified by more than one triplet. This redundancy was confirmed by deciphering the genetic code (refer to Figure 7–27).

The same genetic code is utilized across all present-day organisms, although minor differences have been noted primarily in the mRNA of mitochondria, fungi, and protozoa. Mitochondria contain their own DNA replication, transcription, and protein-synthesis machinery, operating independently of the cell's other machinery. The similar genetic codes in fungi and protozoa outweigh their differences.

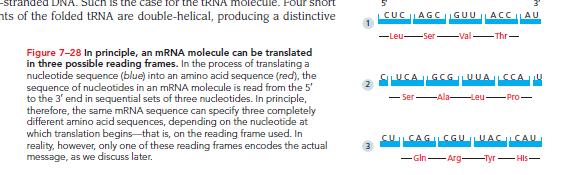

An mRNA sequence can theoretically be translated in three different reading frames, determined by where decoding begins.

. Only one of these frames results in the correct protein, established by a special signal at the beginning of each mRNA that sets the reading frame.

tRNA Molecules Match Amino Acids to Codons in mRNA

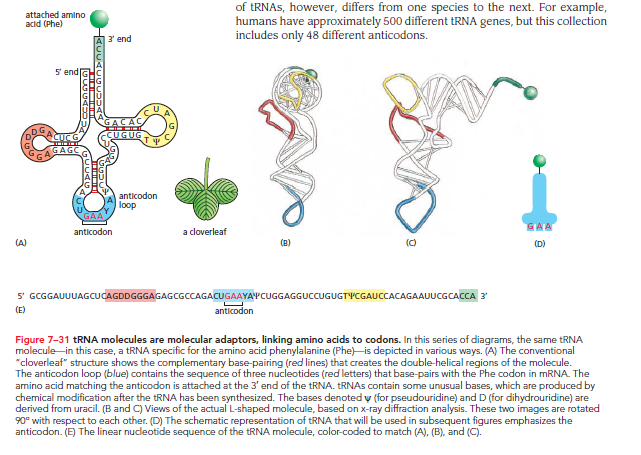

The codons in mRNA do not directly bind to the amino acids they specify. Instead, the translation of mRNA into protein relies on adaptor molecules that bind to a codon on one end and an amino acid on the other. These adaptors are small RNA molecules known as transfer RNAs (tRNAs), each approximately 80 nucleotides in length.

RNA molecules fold into three-dimensional structures through internal base pairing. If the paired regions are extensive enough, they form a double-helical structure similar to double-stranded DNA. The tRNA molecule, for example, forms a distinctive cloverleaf structure that can be seen schematically.

A 5ʹ-GCUC-3ʹ sequence can base-pair with a 5ʹ-GAGC-3ʹ sequence elsewhere in the molecule. Further folding produces an L-shaped structure held together by hydrogen bonds.

Essential functional regions of the L-shaped tRNA molecule include:

Anticodon: A set of three nucleotides that, through base-pairing, binds to the complementary codon in mRNA.

Amino Acid Attachment Site: A short, single-stranded region at the 3ʹ end where the corresponding amino acid is covalently attached.

The redundancy of the genetic code means that multiple codons can specify a single amino acid. This implies the existence of multiple tRNAs for many amino acids or the capability of some tRNAs to base-pair with more than one codon. This phenomenon explains the variations seen in codons differing only by their third nucleotide. Wobble base-pairing allows 20 amino acids to be fitted to 61 codons with at least 31 kinds of tRNA molecules; the diversity in tRNA genes varies by species (e.g., humans have 500 tRNA genes with only 48 different anticodons).

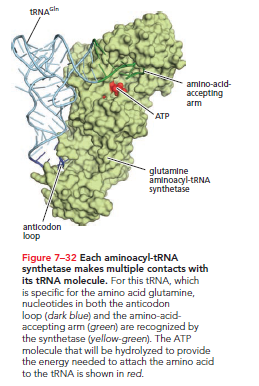

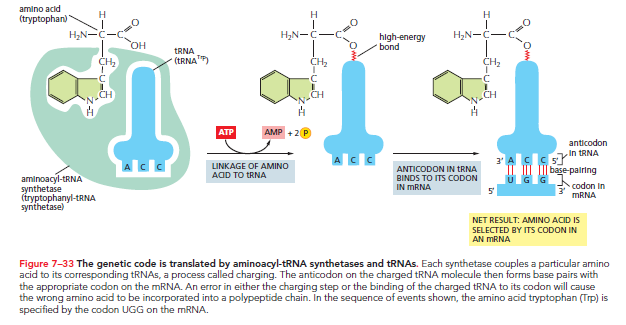

Specific Enzymes Couple tRNAs to the Correct Amino Acid

For tRNA to function as an adaptor, it must be charged with the correct amino acid. This requires enzymes called aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, which covalently link specific amino acids to their respective tRNAs. Typically, each amino acid has its own distinct synthetase, amounting to 20 synthetases total. Each synthetase recognizes its specific amino acid, as well as nucleotides in the tRNA's anticodon loop and amino-acid-accepting arm.

The reaction catalyzed by the synthetase attaches the amino acid to the tRNA's 3ʹ end and is coupled with the energy-releasing hydrolysis of ATP. This reaction results in the formation of a high-energy bond that facilitates the covalent linkage of the amino acid to the growing polypeptide chain.

The mRNA Message Is Decoded on Ribosomes

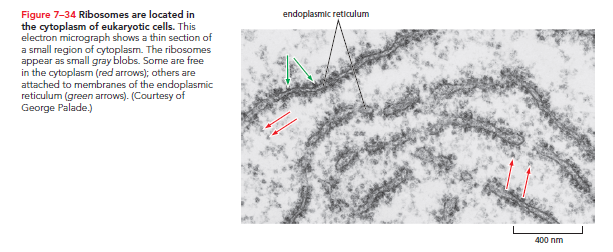

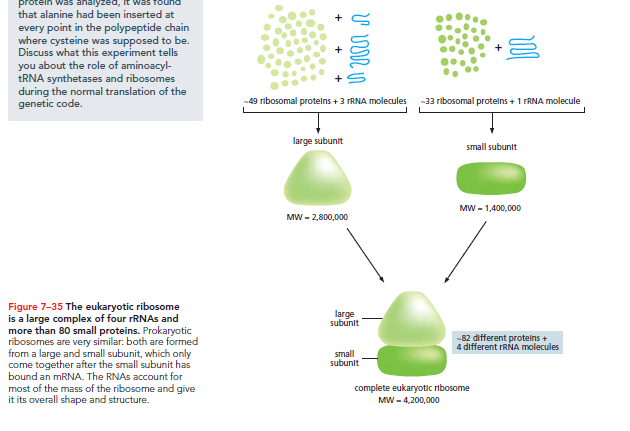

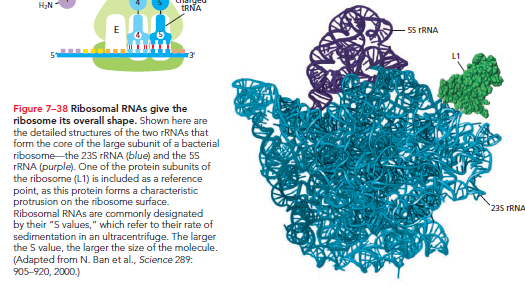

Codon recognition by the tRNA anticodon utilizes complementary base-pairing similar to that in DNA replication. However, efficient mRNA translation into proteins necessitates a complex machine capable of attaching to mRNA, capturing the correct tRNAs, and linking amino acids to generate a polypeptide chain. This machine is the ribosome, made from numerous small ribosomal proteins and several ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). Eukaryotic cells house millions of ribosomes within their cytosol.

Both eukaryotic and prokaryotic ribosomes share structural and functional similarities. Each consists of one large subunit and one small subunit, forming a complete structure with a mass in the millions of daltons.

The small subunit pairs tRNAs with mRNA codons, while the large subunit catalyzes the peptide bond formation among amino acids to create the polypeptide chain.

The ribosome initiates protein synthesis by assembling on an mRNA near the 5ʹ end, pulling the mRNA through as it moves in a 5ʹ-to-3ʹ direction. The ribosome translates mRNA into an amino acid sequence codon by codon, adding each amino acid to the polypeptide chain's end (Movie 7.7). Upon completion of protein synthesis, the ribosome subunits dissociate. Eukaryotic ribosomes add about 2 amino acids every second, while bacterial ribosomes are faster, adding up to 20 amino acids per second.

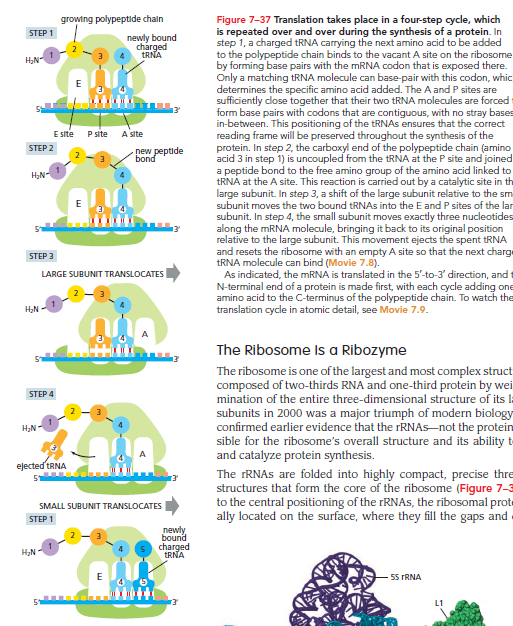

Each ribosome features three binding sites for tRNA: the A site, P site, and E site.

A Site: A charged tRNA enters by base-pairing with the corresponding mRNA codon, linking its amino acid to the growing peptide chain held by the tRNA in the P site.

P Site: The position that holds the growing polypeptide.

E Site: Once the large ribosomal subunit shifts forward, the spent tRNA is moved here before being ejected.

This reaction cycle continues with each added amino acid until a stop codon in the mRNA is recognized, signaling protein release.

The Ribosome Is a Ribozyme

The ribosome comprises two-thirds RNA and one-third protein by weight. Its structural analysis in 2000 confirmed that rRNAs—not proteins—are responsible for the ribosome's overall structure and ability to catalyze protein synthesis.

The rRNAs fold into precise three-dimensional structures to form the ribosome's core.

In contrast, ribosomal proteins primarily stabilize the RNA core and permit conformational changes needed for catalysis. The three tRNA-binding sites (A, P, and E) are formed mainly by rRNAs.

The peptidyl transferase catalytic site for the peptide bond formation is formed by the 23S rRNA of the large subunit, with the nearest protein located too far to contact the incoming amino acid or growing polypeptide.

The ribosome’s catalytic site operates similarly to protein enzymes by providing a structured pocket that orients the reactants—elongating polypeptides and amino acids carried by tRNA—enhancing reaction likelihood.

Ribozymes: RNA molecules with catalytic activity. The discussion will explore additional ribozymes and the implication of RNA-based catalysis for the early evolution of life, suggesting that RNA likely served as the first catalysts in cells. The ribosome represents a remnant of a time when life relied heavily on RNAs.

Specific Codons in an mRNA Signal the Ribosome Where to Start and to Stop Protein Synthesis

In vitro, ribosomes can translate any RNA molecule . However, cells require a specific start signal for translation initiation. The starting site for protein synthesis on an mRNA is critical as it sets the entire reading frame. An error in this stage can misread subsequent codons, resulting in a nonfunctional protein.

Translation begins with the codon AUG, accompanied by a special charged tRNA. This initiator tRNA carries methionine (formylmethionine in bacteria). Newly synthesized proteins thus start with methionine at their N-terminal, typically removed later by proteases.

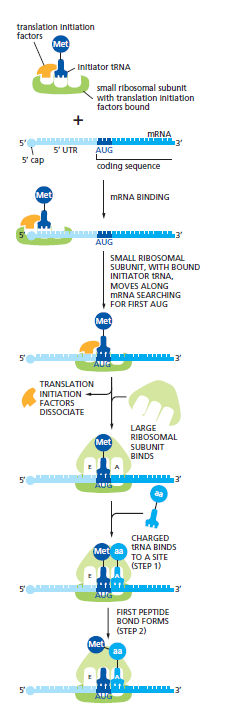

Eukaryotic Initiation: An initiator tRNA, charged with methionine, first loads into the P site of the small ribosomal subunit, alongside translation initiation factors.

The initiator tRNA uniquely binds the P site in the absence of the large ribosomal subunit. The small subunit then binds to the 5ʹ end of the mRNA marked by the 5ʹ cap. Scanning occurs in the 5ʹ-to-3ʹ direction to find AUG; upon recognition, initiation factors dissociate, allowing the large ribosomal subunit to bind and complete assembly. This paves the way for the following charged tRNA to enter the A site.

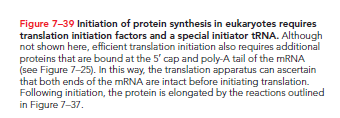

Bacterial Initiation: Bacterial mRNAs lack 5ʹ caps, instead utilizing a specific ribosome-binding sequence upstream of the AUG. Bacterial ribosomes can bind to internal start codons directly if a ribosome-binding site is present. Prokaryotic mRNAs are often polycistronic, encoding several different proteins, with distinct ribosome-binding sites for each coding sequence.

In contrast, eukaryotic mRNA typically encodes a single protein, relying on the 5ʹ cap and associated proteins for ribosome positioning.

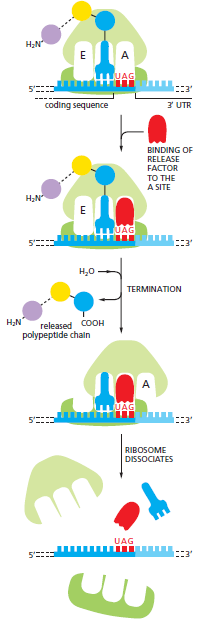

Stop Codons: The end of translation in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes is indicated by stop codons present in the mRNA. The stop codons—UAA, UAG, and UGA—are unrecognized by tRNA and do not specify amino acids. Instead, stop codons signal the ribosome to terminate translation. Release factors bind to the A site upon encountering a stop codon, altering peptidyl transferase activity to facilitate the addition of a water molecule rather than an amino acid.

This process cleaves the polypeptide off the tRNA and releases the completed protein chain. Subsequently, the ribosome disassociates from the mRNA, allowing its subunits to reassemble on another mRNA for a new round of protein synthesis.

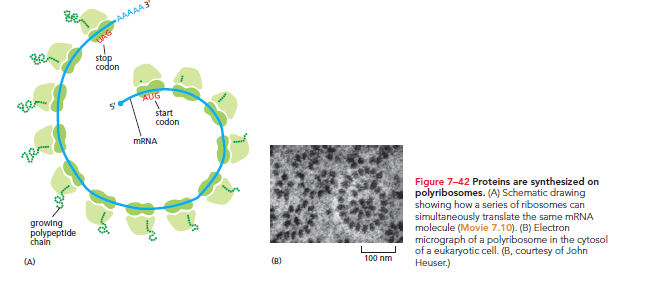

Proteins Are Produced on Polyribosomes

Efficiency: Protein synthesis typically lasts from 20 seconds to several minutes. During this time, multiple ribosomes can bind to each mRNA. When translation is efficient, a new ribosome attaches to the 5ʹ end of an mRNA almost immediately after the preceding ribosome has translated sufficient sequence to move aside. Thus, translated mRNA is often seen as polyribosomes or polysomes, large assemblies made up of various ribosomes spaced 80 nucleotides apart on a single mRNA molecule.

The operation of polysomes allows for increased protein production in a given timeframe compared to sequential synthesis.

Bacterial Efficiency: Polysomes occur in both bacteria and eukaryotes, with bacteria further accelerating protein synthesis. Bacterial mRNA does not require processing and remains accessible during synthesis, allowing ribosomes to attach at the free end and commence translation even before transcription completes. This synchronous operation allows ribosomes to trail closely behind the RNA polymerase as it moves along the DNA.

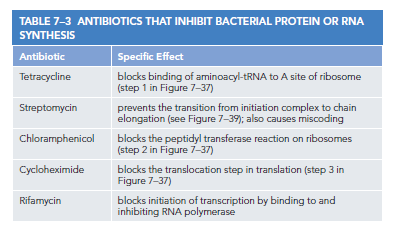

Inhibitors of Prokaryotic Protein Synthesis Are Used as Antibiotics

The ability to accurately translate mRNAs into proteins is a fundamental characteristic of life on Earth. While ribosomes and their associated components are similar across organisms, differences between bacterial and eukaryotic RNA and protein synthesis methods emerged through evolution, providing valuable opportunities in modern medicinal advancements.

Many effective antibiotics act by inhibiting bacterial gene expression without affecting eukaryotic processes. These drugs target the nuanced structural and functional differences between bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes, allowing for selective bacterial protein synthesis disruption while minimizing toxicity to humans. Each antibiotic binds to various bacterial ribosome regions, inhibiting distinct steps in protein synthesis.

Many common antibiotics have been derived from fungi. Fungi and bacteria often occupy shared ecological niches, leading fungi to develop potent toxins that eliminate bacteria while remaining harmless to themselves. Because fungi are eukaryotes, they are closely related to humans, enabling us to utilize these defenses against bacterial threats. However, the evolution of bacterial resistance to these medications presents a continuous challenge.

Controlled Protein Breakdown Helps Regulate the Amount of Each Protein in a Cell

After a protein is synthesized and released from the ribosome, the cell can control its activity and lifespan through various mechanisms. The cell's protein count depends on the rate of new protein synthesis and their respective lifespans. Structural proteins may persist for months or years, whereas metabolic enzymes and regulatory proteins may last only hours, days, or even seconds.

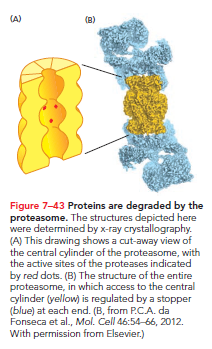

Proteolysis: Cells produce proteolytic enzymes responsible for breaking down proteins into their constituent amino acids, initiating the process of proteolysis. Proteases work by hydrolyzing peptide bonds between amino acids. This process facilitates the acceleration of turnover for proteins with shorter lifetimes while identifying damaged or misfolded proteins for removal. The elimination of misfolded proteins is particularly vital, as these can aggregate, damage cells, and potentially induce cell death.

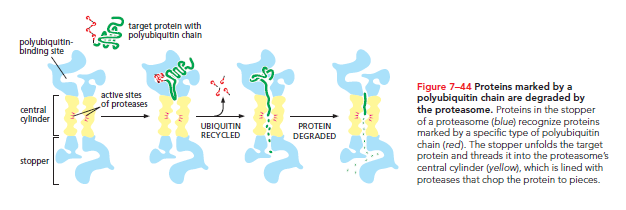

All proteins eventually accumulate damage and undergo proteolysis, enabling amino acids to be recycled for new protein synthesis. Eukaryotic cells utilize proteasomes—large protein complexes located in the cytosol and nucleus—for protein degradation. The proteasome contains a central cylinder of proteases whose active sites face an inner chamber, while each cylinder end is plugged by a protein complex consisting of at least 10 types of subunits.

The proteasome stoppers bind proteins targeted for degradation, using ATP hydrolysis for unfolding and threading them into the inner chamber. Within the chamber, proteases cleave proteins into short peptides that are released at either end. Storing proteases within these molecular chambers avoids uncontrolled enzymatic activity throughout the cell.

Proteasomes select substrates based on a small protein known as ubiquitin. Specialized enzymes label proteins designated for rapid degradation with a polyubiquitin chain, allowing recognition and disassembly by the proteasome.

Short-lived proteins often possess specific sequences indicating they should be ubiquitylated, ensuring they are processed. Damaged or misfolded proteins undergo similar recognition and degradation via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. The enzymes attaching the polyubiquitin chain recognize signals exposed by misfolding or chemical damage, enabling targeted degradation.

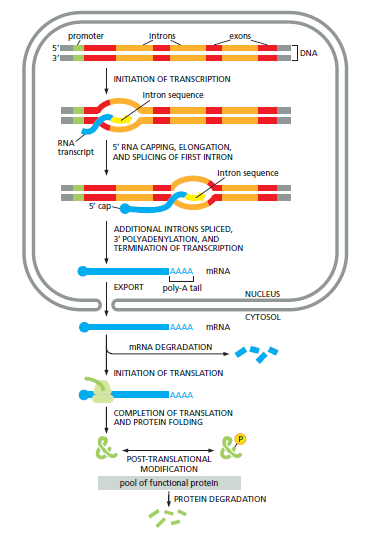

There Are Many Steps Between DNA and Protein

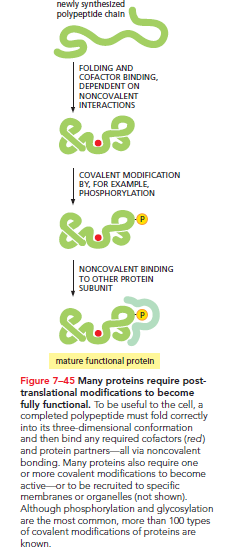

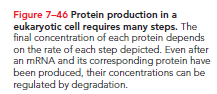

Various steps are necessary to convert a gene's information into a functional protein. In eukaryotic cells, mRNAs must be synthesized, processed, and transported to the cytosol for translation. The process extends beyond mere synthesis: proteins must also attain the correct three-dimensional shape, which can occur spontaneously for some or necessitate the aid of chaperone proteins to prevent aggregation.

Furthermore, proteins may require additional modifications post-translation to achieve functionality. Some undergo covalent modifications, such as phosphorylation or glycosylation, while others interact with small cofactors or assemble with additional subunits. These post-translational modifications are often vital for a synthesized protein to function optimally.

Consequently, the concentration of any given protein hinges on the efficiency of all intervening steps—from DNA to a mature protein.

Ultimately, each step may be modulated, allowing cells to fine-tune protein concentrations based on their needs.