Ch 2

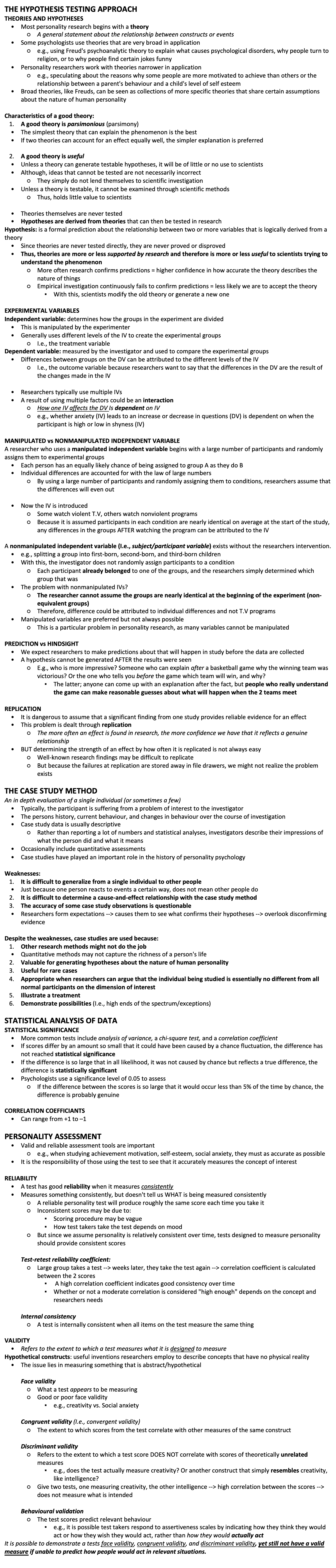

THE HYPOTHESIS TESTING APPROACH

THEORIES AND HYPOTHESES

Most personality research begins with a theory

A general statement about the relationship between constructs or events

Some psychologists use theories that are very broad in application

e.g., using Freud's psychoanalytic theory to explain what causes psychological disorders, why people turn to religion, or to why people find certain jokes funny

Personality researchers work with theories narrower in application

e.g., speculating about the reasons why some people are more motivated to achieve than others or the relationship between a parent's behaviour and a child's level of self esteem

Broad theories, like Freuds, can be seen as collections of more specific theories that share certain assumptions about the nature of human personality

Characteristics of a good theory:

A good theory is parsimonious (parsimony)

The simplest theory that can explain the phenomenon is the best

If two theories can account for an effect equally well, the simpler explanation is preferred

A good theory is useful

Unless a theory can generate testable hypotheses, it will be of little or no use to scientists

Although, ideas that cannot be tested are not necessarily incorrect

They simply do not lend themselves to scientific investigation

Unless a theory is testable, it cannot be examined through scientific methods

Thus, holds little value to scientists

Theories themselves are never tested

Hypotheses are derived from theories that can then be tested in research

Hypothesis: is a formal prediction about the relationship between two or more variables that is logically derived from a theory

Since theories are never tested directly, they are never proved or disproved

Thus, theories are more or less supported by research and therefore is more or less useful to scientists trying to understand the phenomenon

More often research confirms predictions = higher confidence in how accurate the theory describes the nature of things

Empirical investigation continuously fails to confirm predictions = less likely we are to accept the theory

With this, scientists modify the old theory or generate a new one

EXPERIMENTAL VARIABLES

Independent variable: determines how the groups in the experiment are divided

This is manipulated by the experimenter

Generally uses different levels of the IV to create the experimental groups

I.e., the treatment variable

Dependent variable: measured by the investigator and used to compare the experimental groups

Differences between groups on the DV can be attributed to the different levels of the IV

I.e., the outcome variable because researchers want to say that the differences in the DV are the result of the changes made in the IV

Researchers typically use multiple IVs

A result of using multiple factors could be an interaction

How one IV affects the DV Is dependent on IV

e.g., whether anxiety (IV) leads to an increase or decrease in questions (DV) is dependent on when the participant is high or low in shyness (IV)

MANIPULATED vs NONMANIPULATED INDEPENDENT VARIABLE

A researcher who uses a manipulated independent variable begins with a large number of participants and randomly assigns them to experimental groups

Each person has an equally likely chance of being assigned to group A as they do B

Individual differences are accounted for with the law of large numbers

By using a large number of participants and randomly assigning them to conditions, researchers assume that the differences will even out

Now the IV is introduced

Some watch violent T.V, others watch nonviolent programs

Because it is assumed participants in each condition are nearly identical on average at the start of the study, any differences in the groups AFTER watching the program can be attributed to the IV

A nonmanipulated independent variable (I.e., subject/participant variable) exists without the researchers intervention.

e.g., splitting a group into first-born, second-born, and third-born children

With this, the investigator does not randomly assign participants to a condition

Each participant already belonged to one of the groups, and the researchers simply determined which group that was

The problem with nonmanipulated IVs?

The researcher cannot assume the groups are nearly identical at the beginning of the experiment (non-equivalent groups)

Therefore, difference could be attributed to individual differences and not T.V programs

Manipulated variables are preferred but not always possible

This is a particular problem in personality research, as many variables cannot be manipulated

PREDICTION vs HINDSIGHT

We expect researchers to make predictions about that will happen in study before the data are collected

A hypothesis cannot be generated AFTER the results were seen

E.g., who is more impressive? Someone who can explain after a basketball game why the winning team was victorious? Or the one who tells you before the game which team will win, and why?

The latter; anyone can come up with an explanation after the fact, but people who really understand the game can make reasonable guesses about what will happen when the 2 teams meet

REPLICATION

It is dangerous to assume that a significant finding from one study provides reliable evidence for an effect

This problem is dealt through replication

The more often an effect is found in research, the more confidence we have that it reflects a genuine relationship

BUT determining the strength of an effect by how often it is replicated is not always easy

Well-known research findings may be difficult to replicate

But because the failures at replication are stored away in file drawers, we might not realize the problem exists

THE CASE STUDY METHOD

An in depth evaluation of a single individual (or sometimes a few)

Typically, the participant is suffering from a problem of interest to the investigator

The persons history, current behaviour, and changes in behaviour over the course of investigation

Case study data is usually descriptive

Rather than reporting a lot of numbers and statistical analyses, investigators describe their impressions of what the person did and what it means

Occasionally include quantitative assessments

Case studies have played an important role in the history of personality psychology

Weaknesses:

It is difficult to generalize from a single individual to other people

Just because one person reacts to events a certain way, does not mean other people do

It is difficult to determine a cause-and-effect relationship with the case study method

The accuracy of some case study observations is questionable

Researchers form expectations --> causes them to see what confirms their hypotheses --> overlook disconfirming evidence

Despite the weaknesses, case studies are used because:

Other research methods might not do the job

Quantitative methods may not capture the richness of a person's life

Valuable for generating hypotheses about the nature of human personality

Useful for rare cases

Appropriate when researchers can argue that the individual being studied is essentially no different from all normal participants on the dimension of interest

Illustrate a treatment

Demonstrate possibilities (I.e., high ends of the spectrum/exceptions)

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF DATA

STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE

More common tests include analysis of variance, a chi-square test, and a correlation coefficient

If scores differ by an amount so small that it could have been caused by a chance fluctuation, the difference has not reached statistical significance

If the difference is so large that in all likelihood, it was not caused by chance but reflects a true difference, the difference is statistically significant

Psychologists use a significance level of 0.05 to assess

If the difference between the scores is so large that it would occur less than 5% of the time by chance, the difference is probably genuine

CORRELATION COEFFICIANTS

Can range from +1 to –1

PERSONALITY ASSESSMENT

Valid and reliable assessment tools are important

e.g., when studying achievement motivation, self-esteem, social anxiety, they must as accurate as possible

It is the responsibility of those using the test to see that it accurately measures the concept of interest

RELIABILITY

A test has good reliability when it measures consistently

Measures something consistently, but doesn't tell us WHAT is being measured consistently

A reliable personality test will produce roughly the same score each time you take it

Inconsistent scores may be due to:

Scoring procedure may be vague

How test takers take the test depends on mood

But since we assume personality is relatively consistent over time, tests designed to measure personality should provide consistent scores

Test-retest reliability coefficient:

Large group takes a test --> weeks later, they take the test again --> correlation coefficient is calculated between the 2 scores

A high correlation coefficient indicates good consistency over time

Whether or not a moderate correlation is considered "high enough" depends on the concept and researchers needs

Internal consistency

A test is internally consistent when all items on the test measure the same thing

VALIDITY

Refers to the extent to which a test measures what it is designed to measure

Hypothetical constructs: useful inventions researchers employ to describe concepts that have no physical reality

The issue lies in measuring something that is abstract/hypothetical

Face validity

What a test appears to be measuring

Good or poor face validity

e.g., creativity vs. Social anxiety

Congruent validity (I.e., convergent validity)

The extent to which scores from the test correlate with other measures of the same construct

Discriminant validity

Refers to the extent to which a test score DOES NOT correlate with scores of theoretically unrelated measures

e.g., does the test actually measure creativity? Or another construct that simply resembles creativity, like intelligence?

Give two tests, one measuring creativity, the other intelligence --> high correlation between the scores --> does not measure what is intended

Behavioural validation

The test scores predict relevant behaviour

e.g., it is possible test takers respond to assertiveness scales by indicating how they think they would act or how they wish they would act, rather than how they would actually act

It is possible to demonstrate a tests face validity, congruent validity, and discriminant validity, yet still not have a valid measure if unable to predict how people would act in relevant situations.