PSYC203 Week 19 Discursive Social Psychology - 1pp

Page 1

Course Introduction

Course Name: PSYC203

Title: Discursive Social Psychology

Week: 19

Instructor: Dr. Chris Walton

Institution: Lancaster University

Page 2 - Crises in social psychology: is it social enough?

Crises in Social Psychology

First crisis in social psychology emerged in the late 1960s and early 70s.

Concerns included:

Reductionism

Over-individualism

Sole reliance on experimentation as a methodology

Ignorance of language, history, and culture's role in shaping social behaviour

Impact: Greater relevance concerns raised about social psychology's meaningful contributions to social life. Most pronounced impact in Europe.

Page 3 - Crises in social psychology: is it social enough?

The Emergence of Discursive Social Psychology

Literature:

Jonathan Potter and Margaret Wetherell authored "Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour" (1987).

Page 4

Aims of the Lecture

Objectives:

Outline a discursive psychological approach focusing on:

Historical and theoretical background

Core concepts and processes

Relationship to other social psychology approaches

Limitations and criticisms

Page 5 - Crises in social psychology: is it social enough?

“Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour” (1987):

Influences

Informed by linguistics, sociology, and ethnomethodology.

Methodology:

Emphasizes language and social interaction for investigation

Utilizes qualitative data and analysis methods - e.g. interviews, speeches, discussion groups

Epistemology:

Social constructionist rather than (post)positivist epistemology (Gergen, 1985, 1999)

Primarily British orientation.

Page 6 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Potter & Wetherell, 1987; Edwards & Potter, 1992

Alternative to cognitive and social-cognition approaches

Engages with traditional social psychological topics (e.g., attribution, emotion, prejudice, and racism) in context of discourse and everyday life interactions.

e.g. managing everyday interactional concerns

Page 7 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Augoustinos, Walker & Donaghue (2006) identified four core principles of discursive psychology:

Discourse is Constitutive

Discourse is Functional

Discourse is Built from Discursive Resources and Practices

Discourse Constructs Identities in Talk

Page 8 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Principle 1: Discourse is Constitutive

Inverts the usual positivist, cognitivist relationship that underlies most traditional social psychology,

e.g., Reality → Perception → Discourse

In this view language (discourse) is a neutral medium that reflects a reality ‘out there’ in the world or in the head of the individual.

Instead, DP proposes that discourse is analytically prior to perception and reality,

e.g., Discourse → Perception → Reality

In this view discourse is the medium out of which our exterior and interior worlds (realities) are actively constructed.

Page 9 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Principle 2: Discourse is Functional

People do things in and through discourse; it is a social practice.

People do not merely describe the world, objects, individuals or groups within it, but actively construct versions of those worlds in the course of performing social actions.

Thus, versions of the world are: •

Designed for the social context in which they are located;

Oriented to matters of accountability and self-presentation;

Articulated so as to be persuasive and accepted as ‘reality’, over and above alternative accounts.

Page 10 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Principle 3. Discourse is put together from discursive resources and practices

Discursive resources includes such psychological concepts as ‘attitudes’, ‘stereotypes’, ‘categories’ and ‘emotions’ and related meanings.

They can have a higher level of organisation, ‘interpretative repertoires’ (Potter & Wetherell, 1987) or ‘discourses’ (Parker, 1992), e.g., ‘meritocracy’.

They are put together through linguistic practices, strategies and devices to make an account persuasive and accepted as factual, e.g., idiomatic expressions, claimed consensus, three-part lists etc.

three part lists → people commonly list 3 things e.g. “I do everything in this house: the cooking, cleaning and childcare”

These resources and practices are culturally and historically contingent.

Page 11 - Discursive Psychology: Background

Principle 4: Discourse Constructs Identities in Talk

In constructing versions of the world, discourse also constructs the speaking subject, i.e., it constitutes the identity of the speaker.

People can speak from a range of subject positions (Davies & Harré, 1990), so that people can dynamically manage, or instantiate, their identity, e.g., as a ‘woman’, a ‘daughter’, a ‘feminist’, a ‘student’, and a ‘friend’.

People can also actively resist the identities others ascribe to them.

In this view, identity is not a stable, inner psychological aspect of the individual, rather it is something they actively take on or mobilise in particular contexts to particular ends.

You utilise certain identities when it is beneficial to you

Page 12 - Social constructionist approach to emotion

Culturally specific emotion words

Emotion words and concepts shaped by cultural contexts:

Japanese:

Amae (dependent feeling),

Oime (indebtedness)

German:

Schadenfreude (pleasure at others' misfortune)

Weltshmerz (depression resulting from comparing ideals to real word)

Korean:

Cheong (feeling of we-ness)

Page 13 - Social constructionist approach to emotion

Concepts in Emotional Discourse Harré, 1986, p.4-5.

“Psychologists have always had to struggle against a persistent illusion that in such studies as those of emotions there is something there, the emotion, of which the emotion word is a mere representation.”

“Instead of asking the question, ‘What is anger?’ we would do well to begin by asking, ‘How is the word “anger”, and other expressions that cluster around it, actually used in this or that cultural milieu and type of episode?”

Page 14 - Emotion discourse

Emotion Discourse Overview

“The discursive psychology of emotion deals with how people talk about emotion, whether ‘avowing’ their own or ‘ascribing them to other people, and how they use emotion categories when talking about other things. Emotion discourse is an integral feature of talk about events, mental states, mind and body, personal dispositions, and social relations.” (Edwards, 1997, pp.171)

Focus:

Emotion discourse examines how people communicate emotions, both personally and socially

Integrates the talk about mental states, events, and relationships

Treats emotions as discursive phenomena and examines how people use emotion discourse in everyday life.

Page 15 - Emotion discourse

Rhetorical Positions in Emotion Discourse (Edwards, 1997; 1999).

Emotion vs. Cognition

Rational vs. Irrational

Emotion as Cognitively Grounded and/or cognitively consequential

Event Driven vs. Dispositions

Controllable actions vs. Passive Reactions

Natural vs. Moral (unconscious/automatic vs. social judgement)

Internal states vs. External Behaviour (feelings vs. public expression)

Page 16 - Emotion discourse

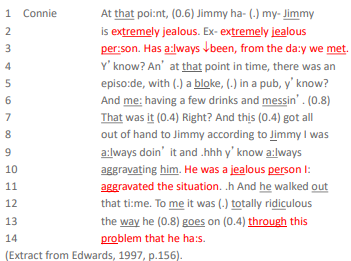

Example of Emotion Discourse (Extract)

Context:

Conversation describes intense jealousy in a situation involving drinking and perceived betrayal.

Illustrates how emotions like jealousy can be constructed and rationalized in discourse.

Page 17 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Cultural Reference:

“…Shilpa Fuckawallah, Shilpa Durupa, Shilpa Poppadom”

-Jade Goody, Celebrity Big Brother 2007

"But that's the way it is in the Army. If someone is slow on the assault course, you'd get people shouting: 'Come on you fat bastard, come on you ginger bastard, come on you black bastard.'"

- Patrick Mercer, Conservative MP, 8th March 2007

Page 18

Recent Political Discourse

Page 19 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Defining Racist Discourse

“ Racist discourse is discourse which has the effect of categorizing, allocating and discriminating betweencertain groups and, in the context of New Zealand, it is discourse which justifies, sustains and legitimates thosepractices which maintain the power and dominance of Pakeha [White] New Zealanders.”

-Wetherell & Potter, 1992, p.70

Page 20 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Denial of Racism in Discourse

Tropes such as “I’m not racist but…” and “I have friends who are black but…” are recurrent features of such talk. (Wetherell & Potter, 1992; Condor, 2006)

Alternatively, accusations of prejudice and discrimination can be recast, by others, as resources used by minority groups in pursuit of their own self interests.

Thus, accusations of prejudice and discrimination can be mobilized as resources in denials of prejudice and discrimination. (Augoustinos et al, 1999).

Page 21 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Focus Group Analysis on Race Relations - Augoustinos, Tuffin & Rapley, 1999

Analysed transcripts of two focus groups of university students on the topic of ‘race relations in Australia’.

Identified four recurring ‘discourses’ that framed discussions of the disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal people:

A colonialist historical narrative of Australia's past;

An economic rationalist/neoliberal discourse on Aboriginal people’s disengagement from productive activity;

A defensive discourse of ‘even-handedness’ that downplayed racism;

A nationalist discourse emphasizing the moral necessity of identifying as ‘Australian’.

Page 22 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

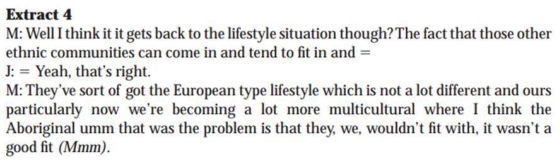

Augoustinos, Tuffin & Rapley, 1999 → 1. A colonialist historical narrative of Australia's past;

Speakers constructed a ‘cultural hierarchy’ with White Europeans as more developed and Aboriginal people as more ‘primitive’. The problem, and the continued disadvantage faced by Aboriginal people, is consequently one of a ‘failure to fit’.

Page 23 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

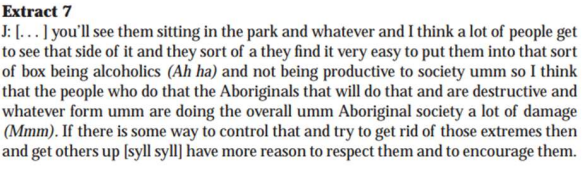

Augoustinos, Tuffin & Rapley, 1999 → 2. Aboriginal people’s disengagement from productive activity

Speakers account for the ‘plight’ of the disadvantaged Aboriginal population by constructing them as the source of the problem by virtue of the self-destructive ‘choices’ they make, ‘victim blaming’.

Page 24 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

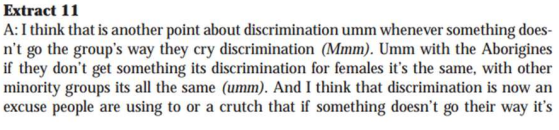

Augoustinos, Tuffin & Rapley, 1999 3. A defensive discourse of ‘even-handedness’ that downplayed racism;

.Speakers appeal to balance or ‘even-handedness’ to argue that racism and discrimination exists on both sides. Claims of racism and discrimination by Aboriginal people (and other minority) groups are constructed as ‘self-interested’, thereby mitigating responsibility on the part of White Australians.

Page 25 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Augoustinos, Tuffin & Rapley, 1999 4. A nationalist discourse emphasizing the moral necessity of identifying as ‘Australian’.

The disadvantage experienced by Aboriginal people is a consequence of their assertion of their Aboriginal identity and their failure to take on the ‘collective’ Australian identity. Victim blaming

Page 26 - A Discursive Psychology of Prejudice

Discourse Functions Beyond Denial

Power Dynamics:

Discusses how identified discourses serve existing power structures and diminishes responsibility of the majority in addressing inequality.

Page 27

Characteristics of Practical Political Rhetoric

Commonplace Tropes:

Themes such as equality for all and accountability for past generations illustrate persistent narratives in political discourse.

Page 28

Implications for Understanding Prejudice

Understanding Prejudice:

Emphasizes that prejudice is reflected in social discourse rather than inherent psychological attributes.

Explores discursive resources speakers use to engage with ethical dilemmas regarding unequal treatment of groups.

Page 29

Criticisms of Discursive Psychology

Critique Points:

Claims of unscientific nature, opaque methods and terminology, subjectivity of findings.

Referenced: Anderson & Wiggins (2013) responses to criticisms.

Page 30

Conclusion: Social Representations Theory vs. Discursive Psychology

Comparative Insights:

Both are social constructionist in nature, focusing on active language use in shaping individual cognition and social processes.

Present ambiguities and criticisms while striving for a more socially grounded psychology.