mod2

When people look at a painting or a sculpture for the first time, the initial question that they usually ask is “What is it?” or “What does it show” Somehow, they expect to see recognizable images in these works of art. Enjoyment of painting, sculpture and literature comes not from their perception of the “meaning” or composition but from the satisfaction they get out of recognizing the subject or understanding the narrative content. Watch the video below.

Play Video

How to analyze the subject matter of an art

The subject of art refers to any person, object, scene, or event described or represented in a work of art. It is the literal, visible image in a work

Types of Subject

Some arts have subject, others do not have. There are two types of subject in arts:

1. Representational or objective art. These are the arts that have subject. Painting, sculpture, the graphic arts, literature, and other theatre arts are generally classified as representational

2. Non-representational or non-objective arts are the arts that do not have subject. The non-objective arts do not present descriptions, stories, or references to identifiable objects or symbols. Rather they appeal directly to the senses primarily because of the satisfying organization of their sensuous and expressive elements. Most musical pieces are not imitations of natural sounds, but we enjoy listening to them because the sounds have been pleasingly arranged and because they evoke certain emotional responses in us. Music, architecture, and many of the functional arts are non- representational. Some musical compositions have subject. They are generally referred to as program music.

Whatever subject an artist chooses, his choice involves some personal statement; it shows what he considers significant or aesthetically satisfying. The value of a work of art does not depend on the artist’s choice of subject. It does not necessarily follow that the more profound the subject, the greater the work of art. Rather, the worth of any representational work of art depends upon the way the subject has been presented. (Caslib Jr., Garing, D. & Casual, J. A. 2018.)

The Content of Art

The content of art includes the connotative, symbolic, and suggestive aspects of the image. Content is the communication of ideas, feelings and reactions connected to the subject. When we look at a painting its content is what is sensed rather that can be analysed. It is the ultimate reason for creating art. Something in the painting must appeal or speak to the heart, spirit and soul of the viewer which is called “emotional content” While subject refers to the objects depicted by the artist, content refers to what the artist expresses or communicates on the whole in his work. Sometimes it is spoken as the “meaning” of the work. Subject matter may acquire different levels of meaning which are the following: (1) factual meaning, (2) conventional meaning, and (3) subjective meaning

The factual meaning is the literal statement or the narrative content in the work which can be directly apprehended because the objects presented are easily recognized.

The conventional meaning refers to the special meaning that a certain object or color has for a particular culture or group of people (i.e. The flag is the agreed-upon symbol for a nation.)

The subjective meaning is any personal meaning consciously or unconsciously conveyed by the artist using a private symbolism which stems from his own association of certain objects, actions, or colors with past experiences. This can be fully understood only when the artist himself explains what he really means. To fully grasp the content of works of art, one must learn as much as he can about the culture of the people that produced them and maintain an open mind.

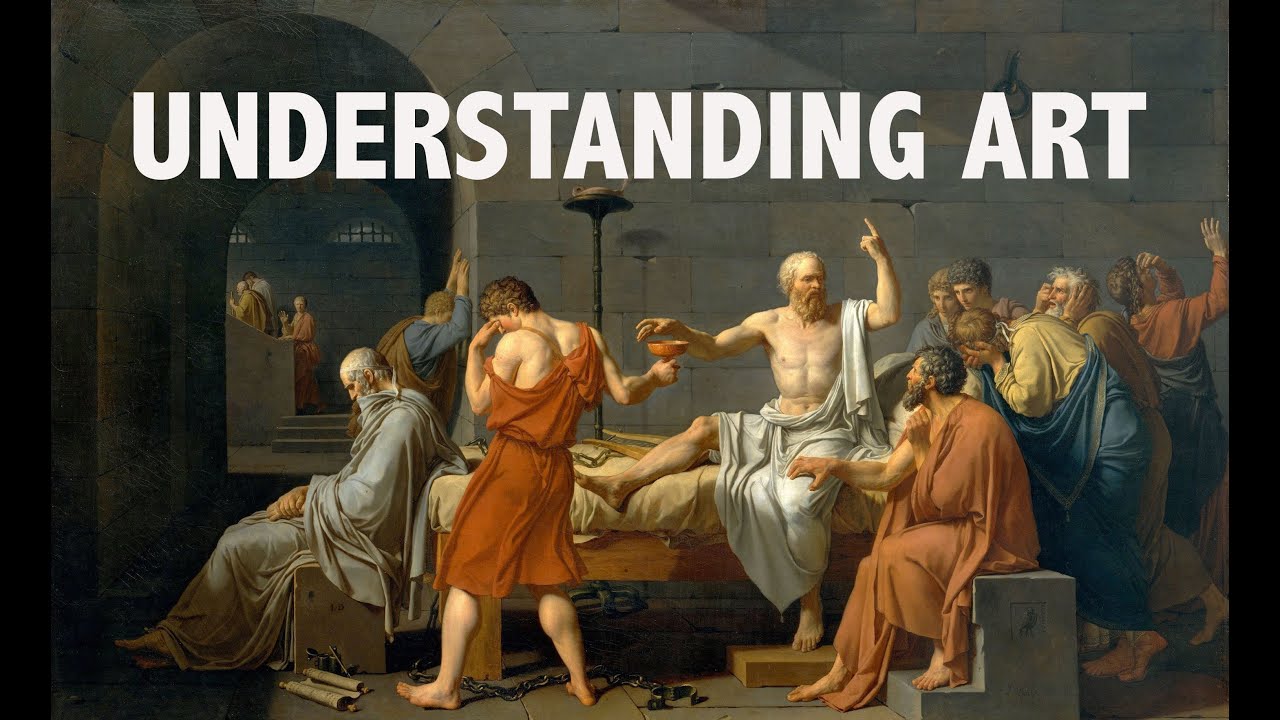

Watch and learn from this video, The Death of Socrates: How To Read A Painting

Play Video

;

Sources and Kinds of Subject

Artists can source their subjects from nature, history, Greek and Roman mythology, Judeo-Christian tradition, sacred oriental texts, religious connections and other works of art.

The subjects depicted in works of art, particularly, the visual arts, can be classified into:

1. Landscapes, seascapes, and cityscapes. Artists have always been fascinated with their physical environment. Since ancient times, landscapes and seascapes have been the favorite subjects of Chinese and Japanese painters who would observe nature, meditate lengthily on its eternal qualities, and paint it in its varying moods. Filipino painters too have captured on canvas the Philippine countryside. Fernando Amoroso romanticized Philippine landscapes, turning the rural areas into idyllic places where agrarian problems are virtually unknown.

In Europe, the painting of pure landscapes without human figures was almost unheard of until Renaissance, when artists began to rediscover their natural environment. But for a time, though, landscapes served only as backgrounds for figures, as in Mona Lisa; or as settings for some religious scenes.

Modern painters seem to be more attracted to scenes in cities. Vicente Manansala, Arturo Luz, and Mauro Malang Santos are among the Filipino painters who have done interesting cityscapes.

2. Still lifes. Some artists love to paint inanimate objects arranged in an indoor setting, flower and fruit arrangements, dishes of food pats and pans, musical instruments and music sheets. The arrangement shows particularly human interest and activities. The still lifes of Chinese and Japanese painters usually show flowers, fruits and leaves in their natural setting, unplucked from the branches. Today the focus is on the exciting arrangement and combinations of the object’s shapes and colors.

3. Animals. They have been represented by artists from almost every age and place. In fact, the earliest known paintings are representation of animals on the walls of waves. The carabao has been a favorite subject of Filipino artists. The Maranaws have an animal form of sarimanok as their proudest prestige symbol. Animals have been used as symbols in conventional religious art.

4. Portraits. People have always been intrigued by the human face as an index of the owner’s character. As an instrument of expression, it is capable of showing a variety of moods and feelings. It is a realistic likeness of a person in sculpture, painting, drawing or print but it needs to be a photogenic likeness. A great portrait is a product of a selective process, the artist highlighting certain features and de-emphasizing others. It does not have to be beautiful but it has to be truthful.

Besides the face, other things are worth noticing in portraits are the subject’s hands, which can be very expressive, his attire and accessories for it reveals much about the subject’s time. Statues and busts of leaders and heroes were quite common among the Romans but it was not until the Renaissance that portrait painting became popular in Europe. Many artists did self- portraits. Their own faces provided them unlimited opportunities for character study.

5. Figures. The sculptor’s chief subject has traditionally been the human body, nude or clothed. The body’s form, structure and flexibility offer the artist a big challenge to depict it in a variety of ways, ranging from the idealistic as in the classical Greek sculptures to the most abstract. The grace and ideal proportions of the human form were captured in religious sculpture by the ancient Greeks. To them physical beauty was the symbol of moral and spiritual perfection; thus they portrayed their gods and goddesses as possessing perfect human shapes. Renaissance artists reawakened an interest in the nude human figure. A favorite subject among painters is the female figure in the nude.

6. Everyday Life. Artists have always shown a deep concern about life around them. Many of them have recorded in paintings their observation of people going about their usual ways and performing their usual tasks. Genre paintings include representations of rice threshers, cock fighters, candle vendors, street musicians and children at play.

7. History and Legend. History consists of verifiable facts, legends of unverifiable ones, although many of them are often accepted as true because tradition has held them so far. Insofar as ancient past is concerned, it is difficult to tell how much of what we know now is history and how much is legend. History and Legend are popular subjects of art. While many works may not be consciously done historical records, certain information about history can be pieced from them-the costumes and accessories, the status symbols, the kinds of dwellings or the means of transportation. Malakas and Maganda and Mariang Makiling are among the legendary subjects which have been rendered in painting and sculpture by not a few Filipino artists.

8. Religion and Mythology. Art has always been a handmaiden of religion. Most of the world’s religions have used the arts to aid in worship, to instruct, to inspire feelings of devotion and to impress and convert non-believers. Pictures of god, human beings, or animals are forbidden in Judaism and Islam because people might worship the images themselves. Other religions have taught that god may sometimes assume human or other visible forms. The ancient Egyptians portrayed their gods as part human and part animal. The ancient African tribes distorted their god’s features. Among the Hindus, Shiva is shown as a four-armed god. Buddha is symbolized by his footprints or a wheel.

9. Dreams and Fantasies. Dreams are usually vague and illogical. Artists especially the surrealists have tried to depict dreams as well as the grotesque terrors and apprehensions that lurk in the depths of the subconscious. A dream may be lifelike situation. Therefore, we would not know if an artwork is based on a dream unless the artist explicitly mentions it. But if the picture suggests the strange, the irrational and the absurd, we can classify it right away as a fantasy or dream although the artist may not have gotten from the idea of a dream at all but the workings of his imagination. No limits can be imposed on an artist’s imagination. (Ortiz, Ma. Aurora R. et. Al.1976).

Reading Article:

Art and the Perception of the World

There is of course more wisdom concerning life that one gets out of The Little Prince by Antoine Saint-Exupery than an insight into the theory of art; nevertheless, it is an insight, and deserves recognition. We are told in this novel that the pilot, as a little boy, used to show his drawing to the adults, and asked them what it is. “It’s a hat,” they replied. But for the boy, it was a boa constrictor having swallowed an elephant!

Consider another drawing of the same kind, we refer to this design:

| |

|  |

There are many ways of looking at this. These are just five of them: (1) a square suspended in a frame, (2) a lampshade seen from above, (3) a lampshade seen from below, (4) a tunnel, and (5) an aerial view of a truncated pyramid. What accounts for the changing visual “aspects”? For psychologists, it is a revelation of personality, like in inkblot experiments. But for the philosophers of art, it is what constitutes the aesthetic perception!

Most of us see a painting as what it is about- the subject. We see, in Sandro Boticelli’s The Birth of Venus, a beautiful golden-haired woman coming out of a shell. We observed bloody, dead gladiators being dragged out of the stadium into the dungeon, amidst the curious glances of Roman spectators, in the Spolarium by Juan Luna. Even in the fragmented, geometrical shapes of Picasso’s Three Musicians, we notice a man with a flute and another one with an accordion or guitar. And when looking at Vincent van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat, we ask: “Who is that?” as if being confronted with a real person.

The fact of our experience is that we often fail to see a painting as a design shapes and lines of different colors and values stumped upon a canvass. And we tend to categorize it to the level of things far removed from what it actually is made of. Yet, the design and the medium visually constitute a painting. If there is more to painting than being visual, it is because we are talking of a different kind of “seeing, “that is “seeing through.” We see through the design, so to speak, in the same way as the boy in The Little Prince saw a huge snake, and as we see a lampshade or a tunnel in the design above. This is our unique experience of art. But should we necessarily “see through” the design in order to ascend to the subject level of a painting in our aesthetic experience of it?

A woman looking at a painting by Henry Matisse was noted to have commented: T have never seen a woman like that!” The painter, who happened to hear the woman, sarcastically responded, “Madame, that is not a woman, that’s a painting!” In the standard of Matisse then, if one sees the painting as its subject, one commits some kind of mistake. But seeing a painting not as representation is a very difficult thing to do. “Man is possessed by an urge to objectivate,” says Herchell Chip, “ he wants to see something in the work of art, and he is sure this represents something.” Some students who for the first time saw van Gogh’s Landscape with Cypresses, protested that nature never looked like that. It took them some times to realize that it was all but a painting, and they exclaimed: “ Ah, van Gogh’s Landscape with Cypresses.”

Of course, there is a great deal of difference, like anything else, between a woman and a painting of a woman in the ontological level, but in the level of sight, these differences disappear. Painting reaching trompe l oeil have so defied vision. An anecdote about Zeuxis and Apollodorus would bring this point to the fore:

As the most famous artists of their time, the rivals held a competition. Zeuxis was said to have painted such a life-like bunch of grapes that the birds came to peck at them. His skill was such that even birds were deceived. Parrhasius, in turn, invited Zeuxis to unveil his painting as was the custom. But as Zeuxis moved to draw the veil, he suddenly realized to his chagrin that the veil itself was the painting. Thus Parrhasius won the competition because his painting, in its versimilitude, fooled not only the birds but a human being.

The true-to-nature approach to painting may be observed in the miniaturismo of the Filipino portrait painters of the 19th century, and in the style called magic realism which might have been influenced by pictures derived from photography. Given that painting is representational, it may be asked: “ What of the world does a painting represent?” By way of answering this question, we shall consider the style of rendering the human form in the Renaissance and cubist paintings.

Portraits were representational and highly realistic during the Renaissance period. The human figure is in the position of rest, either standing or sitting. The face is always in frontal view; it is highly emphasized because the direction of the light and arrangement of objects around are made to focus towards it. The background suggests an illusion of depth which brings the figure affront the eye of the viewer. Leonardo da Vinci’s The Mona Lisa is such a case. If many figures are shown, like in the Last Supper again by da Vinci, they are arranged in a perfectly symmetrical balance achieved by their relative positions in the picture- plane, as determined by the application of linear perspective with its single vanishing point at the center and in the eye level of the observer.

The faithful treatment of figures was abandoned by the cubists during the second decade of 20th century. They brutally distorted it. In Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’ Avignon, is composed of various facet of five female bodies sen from different angles. The facial features of the two women are radically simplified by combining the front and side views. The figures are almost entirely flattened, producing an effect which makes them look immersed on the surface level together with the objects around them. An analytic cubism of the human image is still distinguisable as it is formed by various fragmented, monochromatic, geometrical shapes, like in the Daniel-Henry Kahweiler again by Picasso.

Close consideration of the nature of Renaissance art and cubism as two different styles of figuration indicates that these had developed out of the artists different ways of looking at the world. J. W. Sanders observed:

About 1500, the artists of the Renaissance invented the perspective we are still accustomed to: the artists sat down on his chair, looked at the scene from one definite angle, and tried to fix on his panel accordingly. Now, after four hundred years, the painter rises from his chair. Starts moving around his object, and tries to render the totality. He changes his point of view.

The world the Renaissance saw was static; their paintings captured reality for just one moment, in one view. The cubist turned and wiggle their sight to see many movements, many appearances which resulted in a multi-view, multi-perspective, assorted rendering of thing in artistic forms. This sense of dynamism is one of the most penetrating aspects in the theory of artistic forms. This sense of dynamism is one of the most penetrating aspects in the theory of modern art.

The nature, evolution and appreciation of representational art can therefore be understood in the contexts of the artists’ vision of the world. The relation between art and the world is not that art mirrors nature, as the ancient cliché claimed, but the world as seen by the artists determines the way art becomes. This view, in the final analysis, is the idealist philosophy applied to the theory of art- that we never have a direct contact with the world; we only have an experience of our own, subjective impulses.

Watch and learn from this video:

Knowt

Knowt