China’s First Civilizations

China’s First Civilizations

China’s Geography

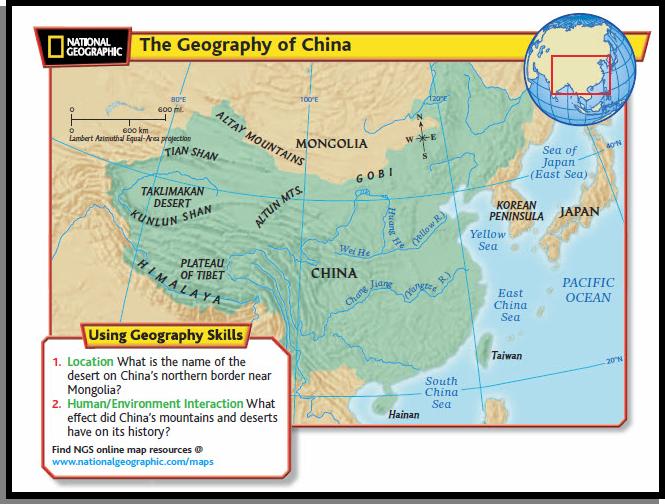

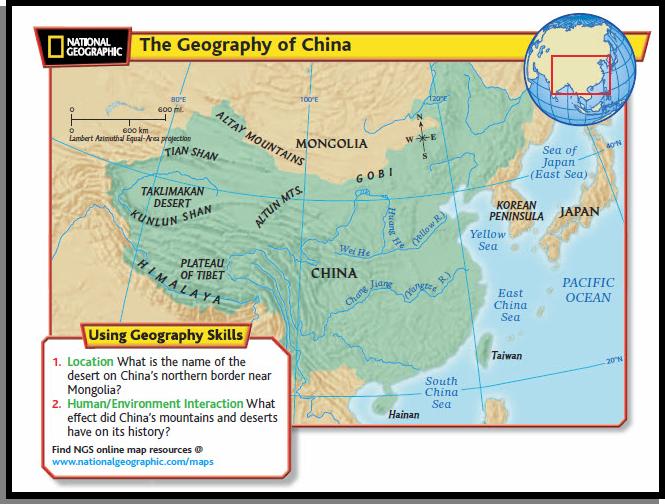

Main Idea: Rivers, mountains, and deserts helped shape China’s civilization.

The Huang He (HWAHNG HUH), or Yellow River, flows across China for more than 2,900 miles (4,666 km). It gets its name

from the rich yellow soil it carries from Mongolia to the Pacific Ocean. Like rivers in early Mesopotamia and Egypt, China’s

Huang He regularly flooded the land. These floods destroyed homes and drowned many people. As a result, the Chinese called the Huang He “China’s sorrow.”

The river, however, also brought a gift. The Huang He is the muddiest river in the world. When the river floods, it leaves

behind rich silt in the Huang He valley, nearly 57 pounds for every cubic yard of topsoil. By comparison, the Nile River in

Egypt only leaves 2 pounds of silt per cubic yard. The soil is so rich that farmers can grow large amounts of food on very small

farms.

China also has another great river, called the Chang Jiang (CHAHNG JYAHNG), or the Yangtze River. The Chang Jiang flows

for about 3,400 miles (5,471 km) east across central China where it empties into the Yellow Sea. Like the Huang He valley, the

Chang Jiang valley also has rich soil for farming.

Even though China has rich soil along its rivers, only a little more than one-tenth of its land can be farmed. That is because

mountains and deserts cover most of the land. The towering Himalaya close off China to the southwest. The Kunlun Shan

and Tian Shan are mountain ranges on China’s western border. The Gobi, a vast, cold, rocky desert, spreads east from the

mountains. These mountains and deserts shaped much of Chinese history. They were like a wall around the Chinese, separating them from most other peoples.

Over time, the Chinese people united to form one kingdom. They called their homeland “the Middle Kingdom.” To them, it

was the world’s center and its leading civilization. The Chinese developed a way of life that lasted into modern times.

The Shang Dynasty

Main Idea: Rulers known as the Shang became powerful because they controlled land and had strong armies.

Little is known about how Chinese civilization began. Archaeologists, however, have found pottery in the Huang He valley

dating back thousands of years. These artifacts show that the Huang He valley was the first center of Chinese civilization.

Archaeologists think that people stayed in the valley and farmed the land because of rich soil. As their numbers expanded, they began building towns, and soon after, the first Chinese civilization began.

China’s first rulers were probably part of the Xia (SYAH) dynasty. A dynasty (DY• nuh•stee) is a line of rulers who belong to the same family. Little is known about the Xia. We know more about the next dynasty, the Shang. The Shang kings ruled from about 1750 B.C. to 1045 B.C.

Who Were the Shang?

Archaeologists have found huge walls, royal palaces, and royal tombs from the time of the Shang.

These remains show that the Shang may have built the first Chinese cities. One of these cities was Anyang (AHN• YAHNG) in

northern China. Anyang was China’s first capital. From there, the Shang kings ruled the early Chinese people.

The people of the Shang dynasty were divided into groups. The most powerful group was the king and his family. The first

Shang king ruled over a small area in northern China. His armies used chariots and bronze weapons to take over nearby areas. In time, the Shang kings ruled over most of the Huang He valley.

Later, Shang kings chose warlords to govern the kingdom’s territories. Warlords are military leaders who command their

own armies. However, the king controlled even larger armies who defended the kingdom’s borders. The king’s armies helped

him stay in power.

Under the king, the warlords and other royal officials made up the upper class. They were aristocrats (uh • RIHS • tuh • KRATS), nobles whose wealth came from the land they owned. Aristocrats passed their land and their power from one generation to the next.

In Shang China, a few people were traders and artisans. Most Chinese, however, were farmers. They worked the land

that belonged to the aristocrats. They grew grains, such as millet, wheat, and rice, and raised cattle, sheep, and chickens. A small number of enslaved people captured in war also lived in Shang China.

Spirits and Ancestors

People in Shang China worshiped gods and spirits. Spirits were believed to live in mountains, rivers,

and seas. The people believed that they had to keep the gods and spirits happy by making offerings of food and other goods. They believed that the gods and spirits would be angry if they were not treated well. Angry gods and spirits might cause farmers to have a poor harvest or armies to lose a battle.

People also honored their ancestors, or departed family members. Offerings were made in the hope that ancestors would help

in times of need and bring good luck. To this day, many Chinese still remember their ancestors by going to temples and burning small paper copies of food and clothing. These copies represent things that their departed relatives need in the afterlife.

Telling the Future

Shang kings believed that they received power and wisdom from the gods, the spirits, and their ancestors. Shang religion and government were closely linked, just as they were in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. An important duty of Shang kings was to contact the gods, the spirits, and ancestors before making important decisions.

The kings asked for the gods’ help by using oracle (AWR• uh • kuhl) bones. They had priests scratch questions on the bones,

such as “Will I win the battle?” and “Will I recover from my illness?” Then the priests placed hot metal rods inside the bones,

causing them to crack. They believed that the pattern of the cracks formed answers from the gods. The priests interpreted the answers and wrote them down for the kings. In this way, kings could make decisions that they believed were guided by the

gods and their ancestors. Scratches on oracle bones are the earliest known examples of Chinese writing.

The Chinese Language

The scratches on oracle bones show how today’s Chinese writing began. However, the modern

Chinese language is much more complex.

Like many other ancient languages, early Chinese writing used pictographs and ideographs. Pictographs (PIHK • tuh • GRAFS)

are characters that stand for objects. For example, the Chinese characters for a mountain, the sun, and the moon are pictographs. Ideographs (IH • dee • uh • GRAFS) are another kind of character used in Chinese writing. They join two or more

pictographs to represent an idea. For example, the ideograph for “east” relates to the idea of the sun rising in the east. It is a combination of pictographs that show the sun coming up behind trees.

Unlike Chinese, English and many other languages have writing systems based on an alphabet. An alphabet uses characters

that stand for sounds. The Chinese use some characters to stand for sounds, but most characters still represent whole words.

Shang Artists

The people in Shang China developed many skills. Farmers produced silk, which weavers used to make colorful clothes. Artisans made vases and dishes from fine white clay. They also carved statues from ivory and a green stone called jade.

The Shang are best known for their works of bronze. To make bronze objects, artisans made clay molds in several sections. Next, they carved detailed designs into the clay. Then, they fit the pieces of the mold tightly together and poured in melted bronze. When the bronze cooled, the mold was removed. A beautifully decorated work of art remained.

Shang bronze objects included sculptures, vases, drinking cups, and containers called urns. The Shang used bronze urns to

prepare and serve food for rituals honoring ancestors.

The Zhou Dynasty

Main Idea: Chinese rulers claimed that the Mandate of Heaven gave them the right to rule.

During the rule of the Shang, a great gap existed between the rich and the poor. Shang kings lived in luxury and began to

treat people cruelly. As a result, they lost the support of the people in their kingdom. In 1045 B.C. an aristocrat named Wu Wang (WOO WAHNG) led a rebellion against the Shang. After defeating the Shang, Wu began a new dynasty called the Zhou (JOH).

The Zhou Government

The Zhou dynasty ruled for more than 800 years—longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history.

Zhou kings ruled much like Shang rulers. The Zhou king was at the head of the government. Under him was a large bureaucracy (byu•RAH• kruh• see). A bureaucracy is made up of appointed officials who are responsible for different areas of government. Like the Shang rulers, the Zhou king was in charge of defending the kingdom.

The Zhou kings copied the Shang system of dividing the kingdom into smaller territories. The kings put aristocrats they

trusted in charge of each territory. The positions the aristocrats held were hereditary. That meant that when an aristocrat died, his son or another relative would take over as ruler of the territory.

The Chinese considered the king their link between heaven and earth. His chief duty was to carry out religious rituals. The

Chinese believed these rituals strengthened the link between them and the gods. This belief paved the way for a new idea that

the Zhou kings introduced to government. They claimed that kings ruled China because they had the Mandate of Heaven.

What Was the Mandate of Heaven?

According to Zhou rulers, a heavenly law gave the Zhou king the power to rule. This

mandate (MAN• DAYT), or formal order, was called the Mandate of Heaven. Based on the mandate, the king was chosen by heavenly order because of his talent and virtue. Therefore, he would rule the people with goodness and wisdom.

The Mandate of Heaven worked in two ways. First, the people expected the king to rule according to the proper “Way,” called the Dao (DOW). His duty was to keep the gods happy. A natural disaster or a bad harvest was a sign that he had failed in his duty. People then had the right to overthrow and replace the king.

The Mandate of Heaven also worked another way. It gave the people, as well as the king, important rights. For example, people had the right to overthrow a dishonest or evil ruler. It also made clear that the king was not a god himself. Of course, each new dynasty claimed it had the Mandate of Heaven. The only way people could question the claim was by overthrowing the dynasty.

New Tools and Trade

For thousands of years, Chinese farmers depended on rain to water their crops. During the Zhou dynasty, the Chinese developed irrigation and flood control systems. As a result, farmers could grow more crops than ever before.

Improvements in farming tools also helped farmers produce more crops. By 550 B.C., the Chinese were using iron plows.

These sturdy plows broke up land that had been too hard to farm with wooden plows. As a result, the Chinese could plow more and produce more crops. Because more food could support more people, the population increased. During the late Zhou dynasty, China’s population had expanded to about 50 million people.

Trade and manufacturing grew along with farming. An important trade item during the Zhou dynasty was silk. Pieces of

Chinese silk have been found throughout central Asia and as far away as Greece. This suggests that the Chinese traded far

and wide.

The Zhou Empire Falls

Over time, the local rulers of the Zhou territories became powerful. They stopped obeying the Zhou kings and set up their own states. In 403 B.C. fighting broke out. For almost 200 years, the states battled each other. Historians call this time the “Period of the Warring States.”

Instead of nobles driving chariots, the warring states used large armies of foot soldiers. To get enough soldiers, they issued laws forcing peasants to serve in the army. The armies fought with swords, spears, and crossbows. A crossbow uses a crank to pull the string and shoots arrows with great force.

As the fighting went on, the Chinese invented the saddle and stirrup. These let soldiers ride horses and use spears and crossbows while riding. In 221 B.C. the ruler of Qin (CHIHN), one of the warring states, used a large cavalry force to defeat the other states and set up a new dynasty.

Summary

Ancient China, a land of profound cultural heritage, has captivated the hearts and minds of scholars and enthusiasts alike. The Chinese people's deep-seated belief in the importance of historical records and the reverence for the written language have been instrumental in preserving their rich cultural legacy. (Han, 1947)

The ancient Han Chinese culture was characterized by a strong emphasis on the philosophy of change, which has inspired researchers to delve deeper into the relationship between cultural heritage and the natural world. (Chen & Han, 2019) This approach has shed light on the unique perspectives of the ancient Chinese on the concept of change and the intricate interplay between people, heritage, and the environment.

Interestingly, a comparative analysis of ancient Greece and China has revealed that while certain key elements of ancient Greek culture may have been absent in early China, this does not necessarily imply cultural superiority. Rather, the differences and similarities between these two ancient civilizations should be examined with an open and nuanced approach, acknowledging the unique contributions and perspectives of each.

Knowt

Knowt