Myers-Psychology-for-AP-Textbook-359-369.docx (copy)

we not-so-wise humans are easily deceived by perceptual illusions, pseudopsychic claims, and false memories.

In this unit, we encounter further instances of these two images of the human condition—the rational and the irrational. We will ponder our memory’s enormous capacity, and the ease with which our two-track mind processes information, with and without our awareness. We will consider how we use and misuse the informa- tion we receive, perceive, store, and retrieve. We will look at our gift for language and consider how and why it develops. And we will reflect on how deserving we are of our species name, Homo sapiens—wise human.

Module 31

Studying and Building Memories

Module Learning Objectives

Define memory.

31-1

Explain how psychologists describe the human memory system. Distinguish between explicit and implicit memories.

31-2

31-3

31-4

Identify the information we process automatically. Explain how sensory memory works.

31-5

31-6

Describe the capacity of our short-term and working memory.

Describe the effortful processing strategies that help us remember new information.

31-7

Describe the levels of processing and their effect on encoding.

31-8

e thankful for memory. We take it for granted, except when it malfunctions. But it is our memory that accounts for time and defines our life. It is our memory that enables us to recognize family, speak our language, find our way home, and locate food and

B

water. It is our memory that enables us to enjoy an experience and then mentally replay and enjoy it again. And it is our memory that occasionally pits us against those whose offenses we cannot forget.

318 Unit VII Cognition

In large part, we are what we remember. Without memory—our storehouse of accu- mulated learning—there would be no savoring of past joys, no guilt or anger over painful recollections. We would instead live in an enduring present, each moment fresh. But each person would be a stranger, every language foreign, every task—dressing, eating, biking—a new challenge. You would even be a stranger to yourself, lacking that continuous sense of self that extends from your distant past to your momentary present.

AP ® Exam Tip

The next three modules deal with memory. Not only is this a

significant topic on the AP® exam, it is also one of the most practical topics in psychology, especially

if you’re a student! Some of your preconceptions about memory may be accurate and some may not. As you read, think about how you can apply what you’re learning in order to be a better student.

Studying Memory

What is memory?

31-1

memory the persistence of learning over time through the encoding, storage, and retrieval of information.

© The New Yorker Collection, 1987, Warren Miller from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

To a psychologist, memory is learning that has persisted over time; it is information that has been acquired, stored, and can be retrieved.

Research on memory’s extremes has helped us understand how memory works. At age 92, my father suffered a small stroke that had but one peculiar effect. He was as mobile as before. His genial personality was intact. He knew us and enjoyed poring over family photo albums and reminiscing about his past. But he had lost most of his ability to lay down new memories of conversations and everyday episodes. He could not tell me what day of the week it was, or what he’d had for lunch. Told repeatedly of his brother-in-law’s

death, he was surprised and saddened each time he heard the news.

At the other extreme are people who would be gold medal winners in a memory Olympics. Russian journalist Shereshevskii, or S, had merely to listen while other reporters scribbled notes (Luria, 1968). You and I could parrot back a string of about 7—maybe even 9—digits. S could repeat up to 70, if they were read about 3 seconds apart in an otherwise silent room. Moreover, he could recall digits or words backward as easily as forward. His accuracy was unerring, even when recalling a list as much as 15 years later. “Yes, yes,” he might recall. “This was a series you gave me once when we were in your apartment. You

were sitting at the table and I in the rocking chair You were wearing a gray

suit. ”

Amazing? Yes, but consider your own impressive memory. You remember countless voices, sounds, and songs; tastes, smells, and textures; faces, places, and happenings. Imagine viewing more than 2500 slides of faces and places for 10 seconds each. Later, you see 280 of these slides, paired with others you’ve never seen. Actual participants in this experiment recognized 90 percent of the

slides they had viewed in the first round (Haber, 1970). In a follow-up experiment, people exposed to 2800 images for only 3 seconds each spotted the repeats with 82 percent accu- racy (Konkle et al., 2010).

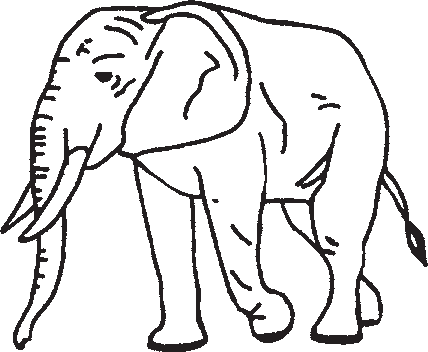

Figure 31.1

What is this? People who had, 17 years earlier, seen the complete image (in Figure 31.4 when you turn the page) were more likely to

recognize this fragment, even if they had forgotten the earlier experience (Mitchell, 2006).

Or imagine yourself looking at a picture fragment, such as the one in FIGURE 31.1. Also imagine that you had seen the complete picture for a couple of seconds 17 years earlier. This, too, was a real experiment, and participants who had previously seen the complete drawings were more likely to identify the objects than were members of a control group (Mitchell, 2006). Moreover, the picture memory reappeared even for those who did not con- sciously recall participating in the long-ago experiment!

How do we accomplish such memory feats? How does our brain pluck information out of the world around us and tuck that information away for later use? How can we remem- ber things we have not thought about for years, yet forget the name of someone we met a minute ago? How are memories stored in our brains? Why will you be likely, later in this module, to misrecall this sentence: “The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”? In this and the next two modules, we’ll consider these fascinating questions and more, including tips on how we can improve our own memories.

Studying and Building Memories Module 31 319

Memory Models

How do psychologists describe the human memory system?

31-2

Architects make miniature house models to help clients imagine their future homes. Simi- larly, psychologists create memory models to help us think about how our brain forms and retrieves memories. Information-processing models are analogies that compare human mem- ory to a computer’s operations. Thus, to remember any event, we must

get information into our brain, a process called encoding.

retain that information, a process called storage.

later get the information back out, a process called retrieval.

Like all analogies, computer models have their limits. Our memories are less literal and more fragile than a computer’s. Moreover, most computers process information sequential- ly, even while alternating between tasks. Our dual-track brain processes many things simul- taneously (some of them unconsciously) by means of parallel processing. As you enter the lunchroom, you simultaneously—in parallel—process information about the people you see, the sounds of voices, and the smell of the food.

To focus on this complex, simultaneous processing, one information-processing mod- el, connectionism, views memories as products of interconnected neural networks. Specific memories arise from particular activation patterns within these networks. Every time you learn something new, your brain’s neural connections change, forming and strengthening pathways that allow you to interact with and learn from your constantly changing environ- ment.

To explain our memory-forming process, Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin (1968) proposed another model, with three stages:

We first record to-be-remembered information as a fleeting sensory memory.

From there, we process information into short-term memory, where we encode it through rehearsal.

Finally, information moves into long-term memory for later retrieval.

Other psychologists have updated this model (FIGURE 31.2) to include important newer concepts, including working memory and automatic processing.

WORKING MEMORY

Alan Baddeley and others (Baddeley, 2001, 2002; Engle, 2002) challenged Atkinson and Shiffrin’s view of short-term memory as a small, brief storage space for recent thoughts and experiences. Research shows that this stage is not just a temporary shelf for holding incom-

encoding the processing of information into the memory system—for example, by extracting meaning.

storage the process of retaining encoded information over time.

retrieval the process of getting information out of memory storage.

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the

brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Contrasts with the step-by-step (serial) processing of most computers and of conscious problem solving.

sensory memory the immediate, very brief recording of sensory information in the memory system.

short-term memory activated memory that holds a few items briefly, such as the seven digits

of a phone number while dialing, before the information is stored or forgotten.

long-term memory the relatively permanent and limitless storehouse of the memory system. Includes knowledge, skills, and experiences.

You will see several versions of Figure 31.2 as you work your way through Modules 31, 32, and 33. Pay attention! This model may look confusing now, but will make more and more sense as its components are described in more detail.

AP ® Exam Tip

ing information. It’s an active desktop where your brain pro- cesses information, making sense of new input and linking it with long-term memories. Whether we hear eye-screem as “ice cream” or “I scream” will depend on how the context and our experience guide us in interpreting and encoding the sounds.

Automatic processing

Figure 31.2

A modified three-stage processing model of memory Atkinson and Shiffrin’s classic three-step model helps us to think about how memories are processed, but today’s researchers recognize other ways long-term memories form. For example, some information slips into long- term memory via a “back door,” without our consciously attending to it (automatic processing). And so much active processing occurs in the short-term memory stage that many now prefer the term working memory.

Attention to important or novel information

Sensory input

Maintenance rehearsal

Encoding

Long-term memory storage

Encoding Retrieving

Working/short- term memory

Sensory memory

External events

320 Unit VII Cognition

Figure 31.3

Working memory Alan Baddeley’s (2002) model of working memory, simplified here, includes visual and auditory rehearsal of new information. A hypothetical

central executive (manager) focuses attention and pulls information from long-term memory to help make sense of new information.

Auditory rehearsal

(Example: Mentally repeating a password long enough to enter it online)

Central executive (focuses attention)

Visual- spatial information

(Example: Mentally rearranging furniture in a room)

Long-term memory

To emphasize the active processing that takes place in this middle stage, psychologists use the term working memory. Right now, you are using your working memory to link the informa- tion you’re reading with your previously stored information (Cowan, 2010; Kail & Hall, 2001). The pages you are reading may enter working memory through vision. You might also repeat the information using auditory rehearsal. As you integrate these memory inputs with your existing long-term memory, your attention is focused. Baddeley (2002) suggested a

central executive handles this focused processing (FIGURE 31.3).

Figure 31.4

Now you know People who had seen this complete image were, 17 years later, more likely to recognize the fragment in Figure 31.1.

Without focused attention, information often fades. In one experiment, people read and typed new information they would later need, such as “An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain.” If they knew the information would be available online, they invested less energy in remembering, and they remembered the trivia less well (Sparrow et al., 2011). Sometimes Google replaces rehearsal.

Before You Move On

c ASK YOURSELF

How have you used the three parts of your memory system (encoding, storage, and retrieval) in learning something new today?

c TEST YOURSELF

Memory includes (in alphabetical order) long-term memory, sensory memory, and working/ short-term memory. What’s the correct order of these three memory stages?

Answers to the Test Yourself questions can be found in Appendix E at the end of the book.

working memory a newer understanding of short-term memory that focuses on conscious, active processing of incoming auditory and visual-spatial information, and of information retrieved from long-term memory.

explicit memory memory of facts and experiences that one can consciously know and “declare.” (Also called declarative memory.)

effortful processing encoding that requires attention and conscious effort.

automatic processing unconscious encoding of incidental information, such as space, time, and frequency, and of well-learned

information, such as word meanings.

implicit memory retention independent of conscious recollection. (Also called nondeclarative memory.)

Building Memories: Encoding

Dual-Track Memory: Effortful Versus Automatic Processing

How do explicit and implicit memories differ?

31-3

As we have seen throughout this text, our mind operates on two tracks:

Atkinson and Shiffrin’s model focused on how we process our explicit memories—the facts and experiences we can consciously know and declare (thus, also called declarative memories). We encode explicit memories through conscious, effortful processing.

Behind the scenes, outside the Atkinson-Shiffrin stages, other information skips the conscious encoding track and barges directly into storage. This automatic processing, which happens without our awareness, produces implicit memories (also called nondeclarative memories).

Studying and Building Memories Module 31 321

Automatic Processing and Implicit Memories

What information do we automatically process?

31-4

Our implicit memories include procedural memory for automatic skills (such as how to ride a bike) and classically conditioned associations among stimuli.Visiting your dentist, you may, thanks to a conditioned association linking the dentist’s office with the painful drill, find yourself with sweaty palms. You didn’t plan to feel that way when you got to the dentist’s office; it happened automatically.

Without conscious effort you also automatically process information about

space. While studying, you often encode the place on a page or in your notebook where certain material appears; later, when you want to retrieve information about automatic processing, for example, you may visualize the location of that information on this page.

time. While going about your day, you unintentionally note the sequence of its events. Later, realizing you’ve left your backpack somewhere, the event sequence your brain automatically encoded will enable you to retrace your steps.

frequency. You effortlessly keep track of how many times things happen, as when you suddenly realize, This is the third time I’ve run into her today.

Our two-track mind engages in impressively efficient information processing. As one track automatically tucks away many routine details, the other track is free to focus on con- scious, effortful processing. This reinforces an important principle introduced in Module 18’s description of parallel processing: Mental feats such as vision, thinking, and memory may seem to be single abilities, but they are not. Rather, we split information into different components for separate and simultaneous processing.

Effortful Processing and Explicit Memories

Automatic processing happens so effortlessly that it is difficult to shut off. When you see words in your native language, perhaps on the side of a delivery truck, you can’t help but read them and register their meaning. Learning to read wasn’t automatic. You may recall working hard to pick out letters and connect them to certain sounds. But with experience and practice, your reading became automatic. Imagine now learning to read reversed sen- tences like this:

.citamotua emoceb nac gnissecorp luftroffE

At first, this requires effort, but after enough practice, you would also perform this task much more automatically. We develop many skills in this way. We learn to drive, to text, to speak a new language with effort, but then these tasks become automatic.

SENSORY MEMORY

How does sensory memory work?

31-5

Sensory memory (recall Figure 31.2) feeds our active working memory, recording momentary images of scenes or echoes of sounds. How much of this page could you sense and recall with less exposure than a lightning flash? In one experiment (Sperling, 1960), people viewed three rows of three letters each, for only one-

K

Figure 31.5

Total recall—briefly When George Sperling flashed a group of letters similar to this for one-twentieth of a second, people could recall only about half the letters. But when signaled to recall a particular row immediately after the letters had disappeared, they could do so with near-perfect accuracy.

Z R

twentieth of a second (FIGURE 31.5). After the nine letters disappeared, they Q B T

could recall only about half of them.

Was it because they had insufficient time to glimpse them? No. The researcher,

George Sperling, cleverly demonstrated that people actually could see and recall all the letters, but only momentarily. Rather than ask them to recall all nine letters at

S G N

322 Unit VII Cognition

iconic memory a momentary sensory memory of visual stimuli; a photographic or picture-image

memory lasting no more than a few tenths of a second.

echoic memory a momentary sensory memory of auditory stimuli; if attention is elsewhere, sounds and words can still be recalled within 3 or 4 seconds.

FYI

The Magical Number Seven has become psychology’s contribution to an intriguing list of magic sevens—the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World,

the seven seas, the seven deadly sins, the seven primary colors, the seven musical scale notes, the seven days of the week— seven magical sevens.

once, he sounded a high, medium, or low tone immediately after flashing the nine letters. This tone directed participants to report only the letters of the top, middle, or bottom row, respectively. Now they rarely missed a letter, showing that all nine letters were momentarily available for recall.

Sperling’s experiment demonstrated iconic memory, a fleeting sensory memory of vi- sual stimuli. For a few tenths of a second, our eyes register a photographic or picture-image memory of a scene, and we can recall any part of it in amazing detail. But if Sperling delayed the tone signal by more than half a second, the image faded and participants again recalled only about half the letters. Our visual screen clears quickly, as new images are superimposed over old ones.

We also have an impeccable, though fleeting, memory for auditory stimuli, called echo- ic memory (Cowan, 1988; Lu et al., 1992). Picture yourself in class, as your attention veers to thoughts of the weekend. If your mildly irked teacher tests you by asking, “What did I just say?” you can recover the last few words from your mind’s echo chamber. Auditory echoes tend to linger for 3 or 4 seconds.

CAPACITY OF SHORT-TERM AND WORKING MEMORY

What is the capacity of our short-term and working memory?

31-6

George Miller (1956) proposed that short-term memory can retain about seven informa- tion bits (give or take two). Other researchers have confirmed that we can, if nothing distracts us, recall about seven digits, or about six letters or five words (Baddeley et al., 1975). How quickly do our short-term memories disappear? To find out, researchers asked people to remember three-consonant groups, such as CHJ (Peterson & Peterson, 1959). To prevent rehearsal, the researchers asked them, for example, to start at 100 and count aloud backward by threes. After 3 seconds, people recalled the letters only about half the time; after 12 seconds, they seldom recalled them at all (FIGURE 31.6). Without the ac-

tive processing that we now understand to be a part of our working memory, short-term memories have a limited life.

Percentage who recalled consonants

90%

80

70

60

50

40

30

Rapid decay

with no

r

ehearsal

Figure 31.6

Short-term memory decay Unless rehearsed, verbal information may be quickly forgotten. (From Peterson & Peterson, 1959; see also Brown, 1958.)

20

10

0

3 6 9 12 15 18

Time in seconds between presentation of consonants and recall request

(no rehearsal allowed)

Working-memory capacity varies, depending on age and other factors. Compared with children and older adults, young adults have more working-memory capacity, so they can use their mental workspace more efficiently. This means their ability to multitask is rela- tively greater. But whatever our age, we do better and more efficient work when focused, without distractions, on one task at a time. “One of the most stubborn, per- sistent phenomenon of the mind,” notes cognitive psy- chologist Daniel Willingham (2010), “is that when you do two things at once, you don’t do either one as well as when you do them one at a time.” The bottom line: It’s probably a bad idea to try to watch TV, text your friends, and write a psychology paper all at the same time!

EFFORTFUL PROCESSING STRATEGIES

What are some effortful processing strategies that can help us remember new information?

31-7

Research shows that several effortful processing strategies can boost our ability to form new memories. Later, when we try to retrieve a memory, these strategies can make the difference between success and failure.

Studying and Building Memories Module 31 323

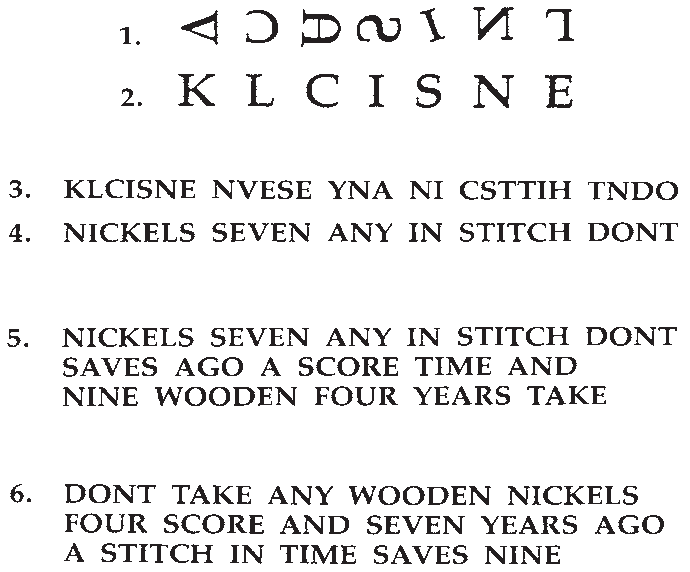

CHUNKING Glance for a few seconds at row 1 of FIGURE 31.7, then look away

and try to reproduce what you saw. Im-

possible, yes? But you can easily repro- duce the second row, which is no less

complex. Similarly, you will probably find row 4 much easier to remember than row 3, although both contain the same letters. And you could remember the sixth cluster more easily than the fifth, although both contain the same words. As these units demonstrate, chunking information—or- ganizing items into familiar, manageable

units—enables us to recall it more easily. Try remembering 43 individual numbers and let- ters. It would be impossible, unless chunked into, say, seven meaningful chunks, such as “Try remembering 43 individual numbers and letters.”☺

Chunking usually occurs so naturally that we take it for granted. If you are a native English speaker, you can reproduce perfectly the 150 or so line segments that make up the words in the three phrases of item 6 in Figure 31.7. It would astonish someone unfamiliar with the language. I am similarly awed at a Chinese reader’s ability to glance at FIGURE

31.8 and then reproduce all the strokes; or of a varsity basketball player’s recall of the posi- tions of the players after a 4-second glance at a basketball play (Allard & Burnett, 1985). We all remember information best when we can organize it into personally meaningful arrangements.

MNEMONICS To help them encode lengthy passages and speeches, ancient Greek scholars and orators also developed mnemonics (nih-MON-iks). Many of these memory aids use vivid imagery, because we are particularly good at remembering mental pictures. We more easily remember concrete, visualizable words than we do abstract words. (When I quiz you later, in Module 33, which three of these words—bicycle, void, cigarette, inherent, fire, process— will you most likely recall?) If you still recall the rock-throwing rioter sentence, it is prob- ably not only because of the meaning you encoded but also because the sentence painted a mental image.

The peg-word system harnesses our superior visual-imagery skill. This mnemonic re- quires you to memorize a jingle: “One is a bun; two is a shoe; three is a tree; four is a door; five is a hive; six is sticks; seven is heaven; eight is a gate; nine is swine; ten is a hen.” Without much effort, you will soon be able to count by peg words instead of numbers: bun, shoe, tree . . . and then to visually associate the peg words with to-be-remembered items. Now you are ready to challenge anyone to give you a grocery list to remember. Carrots? Stick them into the imaginary bun. Milk? Fill the shoe with it. Paper towels? Drape them over the tree branch. Think bun, shoe, tree and you see their associated images: carrots, milk, paper towels. With few errors, you will be able to recall the items in any order and to name any given item (Bugelski et al., 1968). Memory whizzes understand the power of such sys- tems. A study of star performers in the World Memory Championships showed them not to have exceptional intelligence, but rather to be superior at using mnemonic strategies (Maguire et al., 2003).

Chunking and mnemonic techniques combined can be great memory aids for unfamil- iar material. Want to remember the colors of the rainbow in order of wavelength? Think of the mnemonic ROY G. BIV (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). Need to recall the names of North America’s five Great Lakes? Just remember HOMES (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior). In each case, we chunk information into a more familiar form by creating a word (called an acronym) from the first letters of the to-be-remembered items.

Figure 31.7

Effects of chunking on memory When we organize information into meaningful units, such as letters, words, and phrases, we recall it more easily. (From Hintzman, 1978.)

Figure 31.8

An example of chunking—for those who read Chinese After looking at these characters, can you reproduce them exactly? If so, you are literate in Chinese.

chunking organizing items into familiar, manageable units; often occurs automatically.

mnemonics [nih-MON-iks] memory aids, especially those techniques that use vivid imagery and organizational devices.

324 Unit VII Cognition

HIERARCHIES When people develop expertise in an area, they process information not only in chunks but also in hierarchies composed of a few broad concepts divided and subdivided into narrower concepts and facts. This section, for example, aims to help you organize some of the memory concepts we have been discussing (FIGURE 31.9).

Organizing knowledge in hierarchies helps us retrieve information efficiently, as Gor- don Bower and his colleagues (1969) demonstrated by presenting words either randomly or grouped into categories. When the words were organized into categories, recall was two to three times better. Such results show the benefits of organizing what you study—of giving special attention to the module objectives, headings, and Ask Yourself and Test Yourself ques- tions. Taking class and text notes in outline format—a type of hierarchical organization—may also prove helpful.

Figure 31.9

Hierarchies aid retrieval When we organize words or concepts into hierarchical groups, as illustrated here with some of the concepts from this section, we remember them better than when we see them presented randomly.

Mnemonics

Effortful processing strategies

Capacity of short-term and working memory

Effortful processing and explicit memories

Hierarchies

Chunking

Sensory memory

“The mind is slow in unlearning what it has been long in learning.”

-ROMAN PHILOSOPHER SENECA (4 B.C.E.–65 C.E.)

It’s not the studying you do in May that will determine your success on the AP® exam; it’s the studying you do now. It’s a good idea to take a little time each week to quickly review material from earlier in the course. When was the last time you looked at information from the previous units?

AP ® Exam Tip

spacing effect the tendency for distributed study or practice to yield better long-term retention than is achieved through massed study or practice.

testing effect enhanced memory after retrieving, rather than simply rereading, information. Also sometimes referred to as a retrieval practice effect or test-enhanced learning.

shallow processing encoding on a basic level based on the structure or appearance of words.

DISTRIBUTED PRACTICE

We retain information (such as classmates’names) better when our encoding is distributed over time. More than 300 experiments over the last century have consistently revealed the benefits of this spacing effect (Cepeda et al., 2006). Massed practice (cramming) can produce speedy short-term learning and a feeling of confidence. But to paraphrase pioneer memory researcher Hermann Ebbinghaus (1885), those who learn quickly also forget quickly. Distributed practice produces better long-term recall. After you’ve studied long enough to master the material, fur- ther study at that time becomes inefficient (Rohrer & Pashler, 2007). Better to spend that ex- tra reviewing time later—a day later if you need to remember something 10 days hence, or a month later if you need to remember something 6 months hence (Cepeda et al., 2008).

Spreading your learning over several months, rather than over a shorter term, can help you retain information for a lifetime. In a 9-year experiment, Harry Bahrick and three of his family members (1993) practiced foreign language word translations for a given number of times, at intervals ranging from 14 to 56 days. Their consistent finding: The longer the space between practice sessions, the better their retention up to 5 years later.

One effective way to distribute practice is repeated self-testing, a phenomenon that re- searchers Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke (2006) have called the testing effect. In this text, for example, the testing questions interspersed throughout and at the end of each module and unit offer such opportunities. Better to practice retrieval (as any exam will de- mand) than merely to reread material (which may lull you into a false sense of mastery).

The point to remember: Spaced study and self-assessment beat cramming and rereading. Practice may not make perfect, but smart practice—occasional rehearsal with self-testing— makes for lasting memories.

LEVELS OF PROCESSING

What are the levels of processing, and how do they affect encoding?

31-8

Memory researchers have discovered that we process verbal information at different levels, and that depth of processing affects our long-term retention. Shallow processing encodes on a very basic level, such as a word’s letters or, at a more intermediate level, a word’s sound.

Studying and Building Memories Module 31 325

Making things memorable For suggestions on how to apply the testing effect to your own learning, watch this 5-minute YouTube animation: tinyurl.com/HowToRemember.

Deep processing encodes semantically, based on the meaning of the words. The deeper (more meaningful) the processing, the better our retention.

In one classic experiment, researchers Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving (1975) flashed words at people. Then they asked the viewers a question that would elicit different levels of processing. To experience the task yourself, rapidly answer the following sample questions:

deep processing encoding semantically, based on the meaning of the words; tends to yield the best retention.

Sample Questions to Elicit Processing | Word Flashed | Yes | No |

1. Is the word in capital letters? | CHAIR | ||

2. Does the word rhyme with train? | brain | ||

3. Would the word fit in this sentence? The girl put the on the table. | doll |

Which type of processing would best prepare you to recognize the words at a later time? In Craik and Tulving’s experiment, the deeper, semantic processing triggered by the third question yielded a much better memory than did the shallower processing elicited by the second question or the very shallow processing elicited by question 1 (which was especially ineffective).

MAKING MATERIAL PERSONALLY MEANINGFUL

If new information is not meaningful or related to our experience, we have trouble process- ing it. Put yourself in the place of the students whom John Bransford and Marcia Johnson (1972) asked to remember the following recorded passage:

Are you often pressed for time? The most effective way to cut down on the amount of time you need to spend studying is to increase the meaningfulness of the material. If you can relate the material to your own life—and that’s pretty easy when you’re studying psychology—it takes less time to master it.

AP ® Exam Tip

The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. After the procedure is completed one arranges the materials into different

groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually they will be used once more and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.

When the students heard the paragraph you have just read, without a meaningful context, they remembered little of it. When told the paragraph described washing clothes (some- thing meaningful to them), they remembered much more of it—as you probably could now after rereading it.

326 Unit VII Cognition

Can you repeat the sentence about the rioter that I gave you at this module’s begin- ning? (“The angry rioter threw . . .”) Perhaps, like those in an experiment by William Brewer (1977), you recalled the sentence by the meaning you encoded when you read it (for ex- ample, “The angry rioter threw the rock through the window”) and not as it was written (“The angry rioter threw the rock at the window”). Referring to such mental mismatches, researchers have likened our minds to theater directors who, given a raw script, imagine the finished stage production (Bower & Morrow, 1990). Asked later what we heard or read, we recall not the literal text but what we encoded. Thus, studying for a test, you may remember your class notes rather than the class itself.

Tr y This

Here is another sentence I will ask you about later (in Module 33): “The fish attacked the swimmer.”

We can avoid some of these mismatches by rephrasing what we see and hear into meaningful terms. From his experiments on himself, German philosopher Hermann Ebb- inghaus (1850–1909) estimated that, compared with learning nonsense material, learning meaningful material required one-tenth the effort. As memory researcher Wayne Wickel- gren (1977, p. 346) noted, “The time you spend thinking about material you are reading and relating it to previously stored material is about the most useful thing you can do in learning any new subject matter.”

Psychologist-actor team Helga Noice and Tony Noice (2006) have described how actors inject meaning into the daunting task of learning “all those lines.” They do it by first coming to understand the flow of meaning: “One actor divided a half-page of dialogue into three [intentions]: ‘to flatter,’ ‘to draw him out,’ and ‘to allay his fears.’” With this meaningful sequence in mind, the actor more easily remembered the lines.

We have especially good recall for information we can meaningfully relate to ourselves. Asked how well certain adjectives describe someone else, we often forget them; asked how well the adjectives describe us, we remember the words well. This tendency, called the self- reference effect, is especially strong in members of individualist Western cultures (Symons & Johnson, 1997; Wagar & Cohen, 2003). Information deemed “relevant to me” is processed more deeply and remains more accessible. Knowing this, you can profit from taking time to find personal meaning in what you are studying.

The point to remember: The amount remembered depends both on the time spent learn- ing and on your making it meaningful for deep processing.

Before You Move On

c ASK YOURSELF

Can you think of three ways to employ the principles in this section to improve your own learning and retention of important ideas?

c TEST YOURSELF

What would be the most effective strategy to learn and retain a list of names of key historical figures for a week? For a year?

Answers to the Test Yourself questions can be found in Appendix E at the end of the book.

Studying and Building Memories Module 31 327

Module 31 Review

What is memory?

31-1

Memory is learning that has persisted over time, through the storage and retrieval of information.

How do psychologists describe the human memory system?

31-2

Psychologists use memory models to think and communicate about memory.

Information-processing models involve three processes:

encoding, storage, and retrieval.

The connectionism information-processing model views memories as products of interconnected neural networks.

The three processing stages in the Atkinson-Shiffrin model are sensory memory, short-term memory, and long- term memory. More recent research has updated this

model to include two important concepts: (1) working memory, to stress the active processing occurring in the second memory stage; and (2) automatic processing, to address the processing of information outside of conscious awareness.

How do explicit and implicit memories differ?

31-3

Through parallel processing, the human brain processes many things simultaneously, on dual tracks.

Explicit (declarative) memories—our conscious memories of facts and experiences—form through effortful processing, which requires conscious effort and attention.

Implicit (nondeclarative) memories—of skills and classically conditioned associations—happen without our awareness, through automatic processing.

What information do we automatically process?

31-4

In addition to skills and classically conditioned associations, we automatically process incidental information about space, time, and frequency.

How does sensory memory work?

Sensory memory feeds some information into working memory for active processing there.

31-5

An iconic memory is a very brief (a few tenths of a second) sensory memory of visual stimuli; an echoic memory is a three- or four-second sensory memory of auditory stimuli.

What is the capacity of our short-term and working memory?

31-6

Short-term memory capacity is about seven items, plus or minus two, but this information disappears from memory quickly without rehearsal.

Working memory capacity varies, depending on age, intelligence level, and other factors.

What are some effortful processing strategies that can help us remember new information?

31-7

Effective effortful processing strategies include chunking, mnemonics, hierarchies, and distributed practice sessions.

The testing effect is the finding that consciously retrieving, rather than simply rereading, information enhances memory.

What are the levels of processing, and how do they affect encoding?

31-8

Depth of processing affects long-term retention.

In shallow processing, we encode words based on their

structure or appearance.

Retention is best when we use deep processing, encoding words based on their meaning.

We also more easily remember material that is personally meaningful—the self-reference effect.