Accounting ALL chaps

Accounting synthesis

Chapter 1

All individuals, companies and businesses must keep track of their financial resources and their wealth, so they must keep accounts, which we call ACCOUNTING.

Accounting: The process of identifying, recording, summarizing & analyzing a company’s financial transactions, processing this into information and communicating this information to decision makers.

GOAL: to provide users with structured information; to collect + classify information concerning company activity.

Who uses accounting?

Internal Users

Management: To make day-to-day management decisions, they need to have all the information on the company's situation.

Employees: Attentive to results + signs of the company's good health.

External Users

Investors (owners): use accounting information to decide whether to buy, hold, or sell ownership shares of a company.

Shareholders: Find out about the company's financial health from the annual accounts.

Banks or financial institutions: analyze annual accounts to determine whether they can lend to the company.

Creditors (suppliers): Will check your solvency to see if they can give you credit.

Public authorities: interested in the financial aspect (VAT (tva)+ Tax declaration)

Central Balance Sheet Office: Gathers information from annual accounts and publishes it to the public.

Financial analysts: They try to estimate the figures to be announced by companies.

Accounting objectives

The French commercial code requires that the annual financial statements give a true and fair view of the company's assets and liabilities, financial position, results of operations and cash flows. Financial position and results of the company.

Fundamental Characteristics:

- Relevance: Information must influence decisions by predicting future outcomes or confirming past ones.

- Faithful Representation: Data should be complete, unbiased, and free from errors, accurately reflecting economic reality

Enhancing Characteristics:

- Comparability: Data should be consistent over time and with other entities to support effective comparisons.

- Verifiability: Independent parties should agree that information accurately represents an economic event.

- Timeliness: Information must be available early enough to help users make decisions when it matters most.

Assumptions

Assumptions provide a foundation for the accounting process.

Monetary unit assumption: means that we only record financial transactions that can be expressed in terms of money. This helps us measure economic events and is crucial when using the historical cost principle. `

Ex: You buy a computer for $500, and that's recorded in accounting because it's a money value. However, your computer's performance, though important, isn't recorded because it can't be measured in money terms.

Economic entity assumption: a fundamental accounting principle that requires a clear separation between the financial activities of a business entity and those of its owners and other entities. (Separation between their business expenses and private expenses)

Types of businesses

- Proprietorship: A business owned by one person.

- Partnership: A business owned by two or more persons associated as partners i

- Corporation: a business owned by shareholders

The accounting equation

A business has 2 main things: what it owns (assets) and what it owes (liabilities and equity). Assets are what it owns, like a company's money or property. Liabilities and equity are the rights to those assets, which can belong to people or organizations the company owes (like creditors) and the owners.

Basic eq 🡪 Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Assets should always equal the total of liabilities and equity. Liabilities come first in the equation because they get paid first if the business ends.

This equation works for all types of businesses, whether small like a corner store or huge like a big company. It's the foundation for keeping track of a business's financial transactions.

- Assets: What a company owns , it’s resources.

Ex: restaurant's delivery truck & cash

- Cash

- Accounts receivable / debtors/ receivable (creances): the amount of money owned to you

- Notes receivables (creance client): customers owe you one specific date/period usually w/ an interest rate

- Inventory / stocks / Merchandise inventory: what u are selling.

- Prepaid expenses / prepayment: You paid in advance (EX: rent)

- Property, plant, equipment (PPE) (actifs immobilisés): expected to be used for more than 1 period. EX: land, buildings, equipment, furniture, fixture

- Liabilities: Which are debts and obligations

EX: money owed to suppliers and banks.

- Accounts payable / Creditors / payables: the amount of you owe.

- Notes payable (prét/loan): amount of $$ the company must pay, usually w/ interest

- Accrued liabilities: a liability for an expense you have not yet incurred.

Ex : interest payable, salary payable

- Equity : What's left after subtracting liabilities from assets and represents the owners' claim on the company's assets.

🡪 It can include 2 main parts: share capital (money invested by shareholders when they buy shares) and retained earnings.

- Share capital: owners investment in the corporation

- Retained earnings : The money a company keeps from its profits after paying expenses and dividends. It's used for future growth or to cover unexpected costs.

- Dividends: Payments a company makes to its shareholders, typically from its profits. It's a way for owners to get a share of the company's earnings.

- Expenses: The costs a company incurs to run its business, like rent, wages, and supplies.

So, equity increases when shareholders invest or when the business makes money (revenues) and decreases when the company incurs expenses or pays dividends. This balance between assets, liabilities, and equity is crucial in accounting to keep track of a business's financial health.

Accounting transactions

Business transactions are economic events recorded by accountants. They can be external (involving interactions with outside entities) or internal (happening within the company).

EX: buying cooking equipment from a supplier or paying rent are external transactions, while using cleaning supplies internally is an internal transaction.

Not all company activities result in business transactions. Actions like hiring employees or chatting with customers may or may not lead to transactions. To decide, companies analyze each event to see if it affects the accounting equation's components. If it does, they record it.

Double entry system: Every transaction should have a dual effect on the accounting equation. For instance, if one asset increases, there must be a corresponding decrease in another asset, an increase in a specific liability, or an increase in equity. This process is part of the accounting cycle used by companies to record transactions and prepare financial statements.

Expanded equation : Assets = Liabilities + (Share Capital—Ordinary + Retained Earnings)

Each element has its role:

Share Capital—Ordinary: Represents the investment made by shareholders in exchange for ordinary shares.

Retained Earnings: Reflects changes due to revenues earned, expenses incurred, or dividends paid.

The expanded equation links the financial statements between each other.

Financial statements

- Income statement: shows a company’s financial performance. Its purpose is to show whether the company has made a profit. (Revenues + expenses)

- Statement of retained earnings: Summarizes the changes in retained earnings for a specific period of time. ( net income/loss , dividends )

- Balance sheet / statement of financial position : Shows a companies’ financial position , presented at the end of each accounting period. ( assets , liabilities , equity)

- Statement cashflow : Shows a companies’ cash receipts + payments

- A comprehensive income statement: used when a company, , has items of "other comprehensive income" that are important but not part of the net income. They add these items to the net income to calculate comprehensive income. This statement is usually presented after the traditional income statement.

Types of accounting

Not all companies are subject to the same accounting system. This varies according to : Legal form (SA, SRL,..) , Business sector, Sales, Number of employees.

- Simplified accounting: for small businesses

- Double-entry bookkeeping: Double-entry bookkeeping means that each entry in an account must be matched by a "corresponding" entry. In one account must have a "symmetrical" counterpart in another account; Thus, any amount entered in the accounts will be transcribed twice: once on the debit side of an account, and a second time on the credit side. and a second time to the credit of another account.

- Compta (full diagram): For large companies

- Financial Accounting: Focuses on reporting a company's financial performance and financial position to external users, such as investors and creditors. (provides info for external users)

- Managerial Accounting: Provides internal management with information for planning, decision-making, and control within the organization. (provides info for internal users)

- Forensic Accounting: Investigates financial discrepancies and fraud, often used in legal proceedings.

- Governmental Accounting: Focuses on accounting and financial reporting within government entities

- Public accounting : offer expert service to the general public, in much the same way that doctors serve patients and lawyers serve clients.

- Private accounting : accounting within a specific organization or company

Standard charts of accounts (Plan comptable minimum normalisé) , a document containing all the company's account numbers. It is used to record the company's accounting entries.

Companies must file their annual accounts with the central balance sheet office of the central bank, and this information is made public.

Except for: tradesmen (individuals), small companies with limited liability (SNC, SCOMM, SC, SRL), hospitals, schools, etc.

The presentation and use of accounting are governed by the ACCOUNTING LAW

Chapter 2

Definition:

An account: it’s like a record or a place where you keep track of money or something valuable. In accounting an account is referred to as a T- account

Where the left side is called debit (Dr) and the right side is called credit (Cr). We use these terms in the recording process to describe where entries are made in accounts. When comparing the totals of the two sides, an account shows a debit balance if the total of the debit amounts exceeds the credits. An account shows a credit balance if the credit amounts exceed the debits.

Debit: represents every positive item in the tabular summary a receipt of cash. (Les debit represent une augmentation de Tresorie)

![]() Credit: represent every negative amount represents a payment of cash.

Credit: represent every negative amount represents a payment of cash.

Having increases on one side and decreases on the other reduces recording errors and helps in determining the totals of each side of the account as well as the account balance.

The balance is determined by subtracting one amount from the other. The account balance, a debit of €8,050, indicates that Softbyte had €8,050 more increases than decreases in cash.

![]() Double entry: it’s the fact that every financial transaction has two equal and opposite effects. When you record a transaction, you write it down in two places: one as a debit and the other as a credit. These two entries balance each other, ensuring that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) stays. This system helps track where the money comes from and where it goes, keeping your financial records accurate and organized as well as detection of errors.

Double entry: it’s the fact that every financial transaction has two equal and opposite effects. When you record a transaction, you write it down in two places: one as a debit and the other as a credit. These two entries balance each other, ensuring that the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) stays. This system helps track where the money comes from and where it goes, keeping your financial records accurate and organized as well as detection of errors.

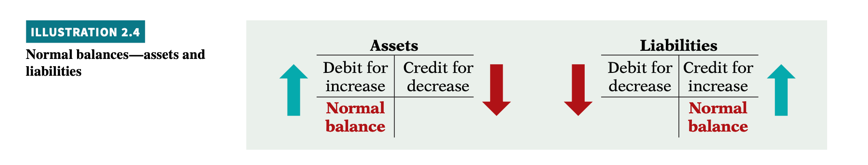

An asset increases on the left side (debit side), and decreases on the right side (credit side).

We know that both sides of the basic equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) must be equal. So liabilities have to be recorded opposite from assets.

Liabilities increase on the right (credit side), and decrease on the left (debit side). Same for equity

The normal balance of an account is on the side where an increase in the account is recorded.

- Asset accounts normally show debit balances. (Debits to an asset account should exceed credits to that account).

Liability accounts normally show credit balances. (Credits to a liability account should exceed debits to that account).

Liability accounts normally show credit balances. (Credits to a liability account should exceed debits to that account).

![]() Since equity is composed of share Capital, Retained Earnings, Dividends, Revenues and Expenses.

Since equity is composed of share Capital, Retained Earnings, Dividends, Revenues and Expenses.

Share Capital—Ordinary: Companies issue share capital—ordinary in exchange for the owners’ investment paid into the company. Credits increase the Share Capital—Ordinary account, and debits decrease. (Acts like liabilities (c’est un passif)

![]()

![]() Retained Earnings: it’s the net income that is kept in the business. It represents the portion of equity that the company has accumulated through the profitable operation of the business. Credits (net income) increase the Retained Earnings account, and debits (dividends or net losses) decrease it. (Acts like liabilities (c’est un passif)

Retained Earnings: it’s the net income that is kept in the business. It represents the portion of equity that the company has accumulated through the profitable operation of the business. Credits (net income) increase the Retained Earnings account, and debits (dividends or net losses) decrease it. (Acts like liabilities (c’est un passif)

Dividends: it’s a company’s distribution to its shareholders. The most common form of distribution is a cash dividend. Dividends reduce the shareholders’ claims on retained earnings. Debits increase the Dividends account, and credits decrease it. (Acts like assest (c’est un actif)

![]() Revenues and Expenses: The purpose of earning revenues is to benefit the shareholders of the business. When a company recognizes revenues, equity increases. So, the effect of debits and credits on revenue accounts is the same as their effect on Retained Earnings. That is, revenue increased by credits and decreased by debits. (Acts like liabilities (c’est un passif)

Revenues and Expenses: The purpose of earning revenues is to benefit the shareholders of the business. When a company recognizes revenues, equity increases. So, the effect of debits and credits on revenue accounts is the same as their effect on Retained Earnings. That is, revenue increased by credits and decreased by debits. (Acts like liabilities (c’est un passif)

Expenses have the opposite effect. Expenses decrease equity. Since expenses decrease net income and revenues increase it, it is logical that the increase and decrease sides of expense accounts should be the opposite of revenue accounts. Thus, expense accounts are increased by debits and decreased by credits. (Expenses acts like asset (c’est un actfi)

Summary of Debit/Credit Rules

The 2nd step in the accounting cycle: The Journal

![]() Journalizing: is entering transaction data in the journal. A complete entry consists of :

Journalizing: is entering transaction data in the journal. A complete entry consists of :

- the date of the transaction (1)

- the accounts and amounts to be debited and credited (2,3)

- a brief explanation of the transaction. (4)

- The column titled Ref. (Reference) is left blank when the journal entry is made. It’s used later when the journal entries are transferred to the individual accounts

!!! In the journal you always have to enter the debit first and then the credit!!!

It is important to use correct and specific account titles in journalizing. Flexibility exists initially in selecting account titles. The main criterion is that each title must appropriately describe the content of the account. Once a company chooses the specific title to use, it should record under that account title all later transactions involving the account.

Simple and Compound Entries

The difference between simple entries and compound entries:

Simple entry is a transaction that only involves two accounts, one debit and one credit but compound entry it’s when transactions require more than two accounts (3, 4 ….or more accounts).

Step 3: The Ledger and Posting

![]() The Ledger : a collection of T-accounts

The Ledger : a collection of T-accounts

In accounting, it’s like a detailed notebook where you keep a record of all your financial transactions. It's where you write down in and out of money in your business and you use it to see the complete history of your financial activities. The ledger provides the balance in each of the accounts as well as keeps track of changes in these balances.

Companies normally use a general ledger. Which contains all the asset, liability, and equity accounts.

Standard Form of Account

This format is called the three-column form of account. It has three money columns—debit, credit, and balance. The balance in the account is determined after each transaction (the total of each account). Companies use the explanation space and reference columns to provide special information about the transaction. The reference column of a ledger account indicates the journal page from which the transaction was posted.

![]() Difference between the Ledger and The Journal:

Difference between the Ledger and The Journal:

The general journal is where transactions are initially recorded in detail, while the ledger is a collection of individual accounts that provide a summary of the financial activity for specific accounts. The general journal is like a diary of transactions, while the ledger is like a set of categorized accounts that show the balances for each account. The information in the general journal is later posted to the ledger to keep track of the balances for each account.

![]() Posting

Posting

Posting is the procedure of transferring journal entries to the ledger accounts. This phase of the recording process accumulates the effects of journalized transactions into the individual accounts. Posting involves the following steps.

Posting should be performed in chronological order. That is, the company should post all the debits and credits of one journal entry before proceeding to the next journal entry. Postings should be made on a timely basis to ensure that the ledger is up-to-date. The reference column of a ledger account indicates the journal page from which the transaction was posted.

![]() 4th step in the cycle: The Trial Balance

4th step in the cycle: The Trial Balance

A trial balance is a list of accounts and their balances at a given time ( c’est une photography a un points T dans l’entrprise). Companies usually prepare a trial balance at the end of an accounting period. Accounts are represented in the same order as in the ledger. Debit balances appear in the left column and credit balances in the right column. The totals of the two columns must be equal. The trial balance proves the mathematical equality of debits and credits after posting.

Under the double-entry system, this equality occurs when the sum of the debit account balances equals the sum of the credit account balances. A trial balance may also uncover errors in journalizing and posting. It’s also useful in the preparation of financial statements.

The steps for preparing a trial balance are:

- List the account titles and their balances in the appropriate debit or credit column.

- Total the debit and credit columns.

- Verify the equality of the two columns.

Chapter 3

Accrual-basis accounting and Adjusting Entries

Creditors, investors, and consumers can not wait for the company to prepare their financial statements because they want to know how well the company performed for a period of time. Solution: accountants divide the economic life of a business into artificial time periods.

This concept is known as the time period assumption or perioding assumption it’s the division of the life of a business into specific time periods, usually one year. This allows us to measure and report the financial performance and financial position of the company at regular intervals, such as annually, quarterly, or monthly.

Fiscal and Calendar Years

Monthly and quarterly time periods are called interim periods.

Fiscal year is an accounting time period that is one year in length. A fiscal year usually begins on the first day of a month and ends 12 months later on the last day of a month. Many businesses use the calendar year (January 1 to December 31) as their accounting period.

Accrual- versus Cash-Basis Accounting

Accrual-basis accounting: It means that you recognize revenue when you make a sale or provide a service, and you record expenses when you receive goods or services, even if the actual payment happens later.

Cash-basis accounting: it’s a method of keeping financial records where you only record income and expenses when actual money changes hands. In other words, you recognize revenue when you receive cash and record expenses when you pay out cash.

Accrual-basis accounting is therefore following International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

![]() Recognizing Revenues and Expenses

Recognizing Revenues and Expenses

Revenue Recognition Principle

Performance obligation: is a promise a company makes to provide a product or service to a customer. When the company meets this performance obligation, it recognizes revenue.

The revenue recognition principle is when a company recognizes revenue in the accounting period in which the performance obligation is satisfied, they do so by performing a service or providing a good to a customer.

![]()

Expense Recognition Principle

Accountants follow a simple rule in recognizing expenses: “Let the expenses follow the revenues.” Thus, expense recognition is tied to revenue recognition.

The expense recognition principle. It requires that companies recognize expenses in the period in which they make efforts (consume assets or incur liabilities) to generate revenue.

Summary of the revenue and expense recognition principles

![]()

The Need for Adjusting Entries

In order for revenues to be recorded in the period in which services are performed and for expenses to be recognized in the period in which they are incurred, companies make adjusting entries.

Adjusting entries ensure that the revenue recognition and expense recognition principles are followed. It is needed every time a company prepares its financial statements.

Adjusting entries are necessary because the trial balance—the first pulling together of the transaction data—may not contain up-to-date and complete data. This is true for several reasons:

- Some events are not recorded daily because it is not efficient to do so.

- Some costs are not recorded during the accounting period because the process is with time rather than as a result of recurring daily transactions. Examples: rent, and insurance.

- Some items may be unrecorded. Example is a bill that will not be received until the next accounting period.

Adjusting entries are required every time a company prepares financial statements.

The company analyzes each account in the trial balance to determine whether it is complete and up-to-date for financial statement purposes. Every adjusting entry will include one income statement account and one balance sheet account.

Types of Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries are classified as either deferrals or accruals.

Adjusting Entries for Deferrals

Deferrals are expenses or revenues that are recognized at a date later than the point when cash was originally exchanged.

There are two types of deferrals : -Prepaid expenses , - unearned revenues

- Prepaid Expenses

Prepaid expenses or prepayments: are costs that you pay in advance for something you will receive or use in the future. It's like paying for a service or product before you actually get it. EX: if you pay your rent for the next month at the end of the current month, that's a prepaid expense. You've paid for the upcoming month's rent in advance.

Prepaid expenses are costs that expire either with the passage of time or through use

Prepaid expenses are recorded as assets on your balance sheet because they represent something of value that you haven't used yet. As time passes and you benefit from what you've prepaid for you gradually recognize these costs as expenses on your income statement. (You increase (a debit) to an expense account and a decrease (a credit) to an asset account.)

- Unearned Revenues

![]() Unearned revenues: are payments you receive in advance for products or services you haven't delivered or provided yet. It's like getting paid for something you promise to do in the future. Now the company has a performance obligation to its customers. Items like rent, magazine subscriptions, and customer deposits are unearned revenues.

Unearned revenues: are payments you receive in advance for products or services you haven't delivered or provided yet. It's like getting paid for something you promise to do in the future. Now the company has a performance obligation to its customers. Items like rent, magazine subscriptions, and customer deposits are unearned revenues.

Unearned revenues are the opposite of prepaid expenses since unearned revenue on the books of one company is likely to be a prepaid expense on the books of the company that has made the advance payment.

Unearned revenues are recorded as liabilities on the balance sheet because they represent an obligation to deliver a product or service in the future.

As the company fulfills its promise and provides the service, it gradually recognizes the unearned revenue as earned revenue on the income statement, reflecting the revenue earned over time. (You decrease (a debit) a liability account and increase (a credit) a revenue account).

Adjusting Entries for Accruals

Accruals are expenses or revenues that are recognized ar an earlier date than the point when cash will be exchanged in the future. The adjusting entry for accruals will increase both the balance sheet account and an income statement account.

- Accrued Revenues

![]() Accrued revenues: It's when you've provided a product or service to a customer, and they owe you money, but they haven't paid you yet. Accrued revenues are recorded on the books to show that you've earned this money, even though it's not in your hands yet.

Accrued revenues: It's when you've provided a product or service to a customer, and they owe you money, but they haven't paid you yet. Accrued revenues are recorded on the books to show that you've earned this money, even though it's not in your hands yet.

It helps keep track of what you're owed and reflects your company's financial performance accurately, matching income with the time when you earned it.

An adjusting entry records the receivable that exists at the statement of financial position date and the revenue for the services performed during the period.

An adjusting entry for accrued revenues results in an increase (a debit) to an asset account and an increase (a credit) to a revenue account.

![]() Summary

Summary

Accrued Expenses

Cost or expenditures that a company has incurred (collected) but has not yet paid or recorded in its financial statements. Ex: interest, taxes, and salaries.

They occur when a company consumes goods or services and is obligated to pay for them in the future, creating a liability.

To account for accrued expenses, companies need to make adjusting entries. These entries are necessary to reflect the financial obligations that exist at the statement of financial position (balance sheet) date and to recognize the expenses that belong to the current accounting period. Without these adjustments, both the liabilities and expenses on the financial statements would be understated.

Debiting an Expense Account: This increases the expense on the income statement, recognizing the cost incurred.

Crediting a Liability Account: This increases the liability on the balance sheet, acknowledging the obligation to pay.

Accrued interest

The interest that accumulates on a debt but has not yet been paid. This interest accrues over time based on the principal amount, the interest rate, and the duration for which the debt is outstanding.

Example

- Yazici Advertising borrowed $5,000 on October 1, and they have to pay it back in three months. The annual interest rate is 12%.

- The interest for one month is $50 ($5,000 principal × 12% annual rate × 1/12).

- At the end of October, Yazici records this accrued interest. They increase "Interest Payable" (money they owe but haven't paid yet) by $50 and also record "Interest Expense" for $50 (the cost of the interest they've incurred during the month).

This way, the company keeps track of its financial obligations and expenses accurately for the current period without understating liabilities or overestimating net income and equity.

Accrued wages & salaries

They occur when a company has incurred salary and wage expenses but hasn't paid them yet. This is common when employees work for a certain period before receiving their paychecks. In accounting, these unpaid expenses are recognized as accrued liabilities until they are paid.

To account for accrued salaries and wages, companies need to make adjusting entries. :

- Adjustment at the End of the Period: As the end of the accounting period approaches, the company assesses the unpaid salaries and wages for the work done in that period. In your example, you have accrued salaries of $1,200 at the end of October.

- Adjusting Entry:

- Debit Salaries and Wages Expense: This increases the expense on the income statement, recognizing the cost incurred. In this case, you debit it with $1,200.

- Credit Salaries and Wages Payable: This recognizes the amount as a liability on the balance sheet, acknowledging the obligation to pay. You credit it with $1,200.

This makes sure that the company's financial statements correctly reflect the amount of salaries and wages incurred and owed during that specific accounting period.

When the company eventually pays the employees, usually in the next accounting period, they'll make another entry to debit Salaries and Wages Payable and credit Cash, effectively reducing the liability and recognizing the cash outflow.

![]() Summary of basic relationships

Summary of basic relationships

Each adjusting entry affects one balance sheet and on income statement.

Step 6 & 7: Adjusted trial balance & financial statements

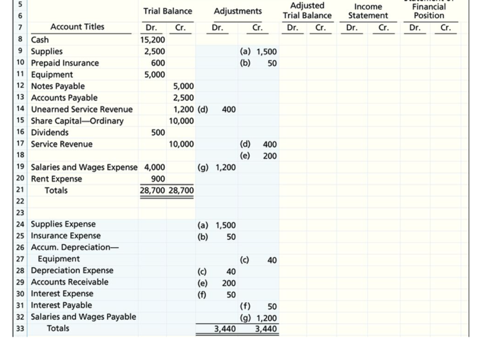

An Adjusted Trial Balance is an important step in the accounting process that helps ensure the accuracy of a company's financial records and forms the foundation for creating financial statements. Here's how it works:

Preparing Adjusted Trial balance

This adjusted trial balance reflects the updated account balances after making adjusting entries. It includes additional accounts like Prepaid Insurance, Notes Payable, Interest Payable, Unearned Service Revenue, and Salaries and Wages Payable, which were affected by the adjusting entries. The purpose of this trial balance is to ensure that the total debits (left side) equal the total credits (right side), which indicates the books are in balance. It is also the basis for preparing financial statements.

Photo

Preparing Financial Statements

Income Statement: Companies create the income statement from the revenue and expense accounts. Revenues are listed at the top, followed by a list of expenses. The total expenses are subtracted from total revenues to calculate the net income or net loss for the period.

Retained Earnings Statement: Using the Retained Earnings account, the statement shows the beginning balance of retained earnings (from the previous period), adds the net income from the income statement, and subtracts any dividends. The result is the ending balance of retained earnings.

Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet): Companies prepare the statement of financial position from the asset and liability accounts in the adjusted trial balance. It includes assets such as cash, equipment, supplies, and accounts receivable, and liabilities like accounts payable, notes payable, and other obligations. The ending balance of retained earnings, as reported in the retained earnings statement, is also included.

The adjusted trial balance serves as the basis for creating these financial statements and ensures that all the accounting data are correctly presented.

Alternative treatment of deferrals

The company handles prepaid expenses and unearned revenues differently in its initial entries and adjusting entries.

- Prepaid Expenses (Alternative Treatment):

- When a company prepays an expense, it debits that amount to an expense account instead of debiting it to an asset account.

- EX: if a company pays for rent in advance, it records the payment as an expense immediately.

- Unearned Revenues (Alternative Treatment):

- When a company receives payment for future services, it credits the amount to a revenue account rather than a liability account.

- This means the company recognizes the revenue immediately, even though the services or products are not yet delivered.

The effect of this alternative approach is that it accelerates the recognition of expenses and revenues, making the financial statements reflect these changes earlier than traditional methods. It can only be used when specific circumstances allow it .

Prepaid expenses

When a company expects to use a prepaid expense (EX : supplies) before the end of the month, they debit (increase) an expense account (EX: Supplies Expense) rather than an asset account (EX: Supplies) at the time of purchase.

This eliminates the need for an adjusting entry at the end of the month. The expense account will show the cost of supplies used between the purchase date and the end of the month.

- Adjusting Entry for Unused Supplies:

- If the company doesn't use all of the supplies, they make an adjusting entry at the end of the month to account for the unused supplies.

- For example, if 1,000 units of advertising supplies remain at the end of the month, an adjusting entry is made to decrease Supplies Expense and increase Supplies by 1,000.

This alternative approach simplifies the accounting process when a company is confident that they will consume prepaid expenses before the end of the period. However, if they end up not using all of the supplies, an adjusting entry is still necessary to ensure accurate financial reporting.

Unearned revenues

In the traditional approach, unearned revenues are initially recorded as liabilities. As services are performed, the liability decreases, and the corresponding revenue increases. However, some companies use a different approach

In an alternative treatment for unearned revenues, companies credit a revenue account when they receive cash for future services expected to be performed within the current period. If the services aren't provided by the period's end, an adjusting entry is made. Without this entry, the revenue is overstated, and the liability account is understated.

EX: if Yazici Advertising received 1,200 on October 2 for services expected to be performed by October 31, they would credit the Service Revenue account. If not all the services are performed, an adjusting entry on October 31 would be made:

Credit Service Revenue: 800 Debit Unearned Service Revenue: 800

This adjustment ensures accurate financial reporting by correctly reflecting revenue and liabilities.

![]() Summary of Additional adjustment relationships

Summary of Additional adjustment relationships

Alternative adjusting entries don’t apply to accrued revenues and accrued expenses because no entries happen before companies make these types of adjusting entries .

Financial reporting concepts

Assumptions

- Monetary unit assumption : means that we only record financial transactions that can be expressed in terms of money.

- Economic entity assumption: a fundamental accounting principle that requires a clear separation between the financial activities of a business entity and those of its owners and other entities. (Separation between their business expenses and private expenses)

- Time period assumption: The belief that financial information should be divided into specific time periods, like months or years, for easier analysis and reporting.

- Going concern assumption: based on the idea that a business will continue its operations indefinitely. It assumes that the company is not facing impending bankruptcy or planning to cease operations.

Principles in Financial Reporting

- Historical Cost Principle: Assets are recorded at their original cost and are not adjusted for changes in market value over time.

- Fair Value Principle: Assets and liabilities are reported at their current market value, when that value is readily available and provides more relevant information.

- Revenue Recognition Principle: Revenue is recognized when a company satisfies its performance obligations, typically when goods are transferred or services are performed.

- Expense Recognition Principle: Expenses are recognized in the same period as the related revenues to accurately match costs with the revenue they help generate.

- Full Disclosure Principle: Companies must disclose all important information that could impact financial statement users in accompanying notes when it cannot be reported directly on the financial statements.

- Cost Constraint: This principle considers the cost of providing certain information against the benefits of having that information for financial statement users, helping to determine whether it should be disclosed.

Chapter 4

The worksheet:

It’s a multiple-column form used in the adjustment process and preparation of financial statements (to make one we need excel). A company CAN NOT publish it to external users. The completed worksheet is not a substitute for formal financial statements.

![]()

- IT’S NOT A JOURNAL OR A GENERAL LEDGER but a working tool.

- The use of it is optional but it offers the opportunity for the company to directly do their financial statement on this Excel document.

Step-by-step preparation of a worksheet:

Prepare your trail balance:

Prepare your trail balance:

Enter all the ledger accounts with their balances in the account titles column. Then enter debit and credit amounts from the ledger in the trial balance columns.

- Enter the Adjustments in the Adjustments Columns (keying):

Enter all adjustments in the adjustment columns. 2 things can happen:

- If an account that is already in the trail balance needs an adjustment, put the adjustment amount next to it.

- If additional accounts need to be adjusted, insert them below “account titles”.

- Enter Adjusted Balances in the Adjusted Trial Balance Columns:

Now, combine the trial balance and the adjustments account together for each account.

Remember:

If the account is in debit in the trial balance and you have to credit it in the adjustment it means that in the adjusted trial balance you have to subtract both

If the account is in debit in the trial balance and you have to credit it in the adjustment it means that in the adjusted trial balance you have to subtract both

- If the account is in debit in the trial balance and you have to debit it in the adjustment it means that you have to add both

- If the account is credited in the train balance and you have to debit it in the adjustment it means that you just need to subtract both

- If the account is credited in the train balance and you have to credit it in the adjustment it means that you have to add both

Extend Adjusted Trial Balance Amounts to Appropriate Financial Statement Columns

Extend Adjusted Trial Balance Amounts to Appropriate Financial Statement Columns

Next, place the correct account in the income statement and the statement of financial position

Rapple:

- Income statement: ONLY revenues, expenses, and account receivable.

- Balance sheet is ONLY assets, liability, and equity

- Total the Statement Columns, Compute the Net Income (or Net Loss), and Complete the Worksheet

![]()

Finally, we have to total each column of the financial statements.

Same rule as before: To find the net income or loss, subtract the totals of the debit and credit in the income statement columns.

- If the total credits exceed the total debits, the result is net income.

Consequently: you must enter the amount in the debit of the income statement and in the statement of financial position in the credit column. (The credit in the statement of financial position indicates the increase in equity caused by net income.)

What if instead of the net income we had a net loss?

We would just put the result in the credit side of our income statement and debit our statement of financial position. Consequently, the debit in the statement of financial position indicates the decrease in equity caused by net loss.)

Preparing Financial Statements from a Worksheet

Now that the worksheet is complete, the company can now prepare its financial statement on individual sheets.

Remember that the retained earnings statement is prepared from the statement of financial position columns because it just takes into account the retained earnings and dividends.

Preparing Adjusting Entries from a Worksheet: (NO)

- To adjust the accounts, the company must journalize the adjustments and post them to the ledger because a worksheet cannot be used for that.

- (The reference letters in the adjustment columns and the explanations of the adjustments at the bottom of the worksheet help identify the adjusting entries)

Closing the Books:

When they say “Closing the books” it means that the company is preparing their accounts for the next period. They do this at end of the accounting period.

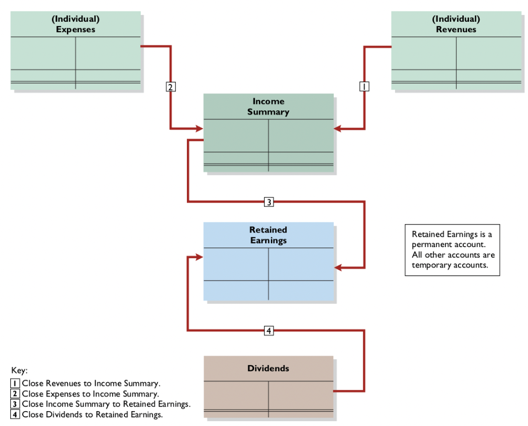

![]() Closing the book we can distinguish:

Closing the book we can distinguish:

- Temporary accounts: Accounts that will stay for only this accounting period meaning that at the end of the period they will be closed.

- They include all income statement accounts and the dividends account.

- Permanent accounts: Accounts that will stay for more than an accounting period, they will be carried from period to period in the company

- They consist of all statements of financial position accounts.

Preparing Closing Entries

In preparing closing entries, companies transfer the revenue and expense accounts to the “Income Summary”, after that they transfer the resulting net income or net loss from this account to Retained Earnings. And then they add dividends to the retained earnings. Companies usually record closing entries in the general journal.

- Income Summary: is only used in closing entries.

At this time:

- All temporary accounts have a balance of zero, to accumulate data in the next accounting period.

- Permanent accounts have the same value at the closing entry and the beginning of the entry.

![]()

Closing Process :

- Debit each revenue account for its balance, and credit the Income Summary for total revenues.

- Debit Income Summary for total expenses, and credit each expense account for its balance.

- Debit Income Summary and credit Retained Earnings for the amount of net income.

Debit Retained Earnings for the balance in the Dividends account, and credit Dividends for the same amount

Debit Retained Earnings for the balance in the Dividends account, and credit Dividends for the same amount

(They close net income in retained earnings and they add dividend to it)

Rappel: Dividends are not an expense, and they are not a factor in determining net income.

Posting Closing Entries:

After posting the closing entries, all temporary accounts have a balance of zero.

The balance in Retained Earnings represents the accumulated undistributed earnings of the company at the end of the accounting period. This balance is shown on the statement of financial position and is the ending amount reported on the retained earnings statement.

In the closing process, a company will double-underline its temporary accounts and draw a single underline beneath the permanent accounts and they will be carried forward to the next period.

Preparing a Post-Closing Trial Balance:

After a company has journalized and posted all closing entries, they will prepare another trial balance, called a post-closing trial balance. It does not consider the temporary account because their balance is equal to 0 at the end of the fiscal year but it lists permanent accounts and their balances after the journalizing and posting of closing entries.

The purpose: prove the equality of the permanent account balances carried forward into the next accounting period.

Reversing Entries (Optional Step):

A reversing entry is the exact opposite of the adjusting entry. Use of reversing entries is an optional bookkeeping procedure; it is not a required step in the accounting cycle.

Correcting Entries (An Avoidable Step):

Unfortunately, errors may occur in the recording process. Companies should correct errors, as soon as they discover them, by journalizing and posting correcting entries.

Differences between correcting entries and adjusting entries.

- Adjusting entries are an integral part of the accounting cycle.

- Correcting entries are unnecessary if the records are error-free.

- Companies journalize and post adjustments only at the end of an accounting period, but they can make correcting entries whenever they discover an error.

- Adjusting entries always affect at least one statement of financial position account and one income statement account.

- Correcting entries may involve any combination of accounts in need of correction.

- Correcting entries must be posted before closing entries.

Classified Statement of Financial Position:

The statement of financial position presents a snapshot of a company's financial position at a point in time.

To improve users' understanding of a company's statement of financial position, companies group similar assets and liabilities because some items have similar economic characteristics.

These help financial statement readers determine if the company has enough assets to pay

- Its debts as they come due,

- And short and long-term creditors.

Intangible Assets:

Intangible assets are long-lived assets that are not physical à they will stay for a long time in the company

Ex: goodwill, patents, copyrights, trademarks, property, plant, and equipment

![]() Depreciation: is the practice of allocating the cost of assets to a number of years.

Depreciation: is the practice of allocating the cost of assets to a number of years.

Companies will systematically assign a portion of an asset's cost as an expense each year.

The assets depreciated are reported on the statement of financial position in the account “less: accumulated depreciation”.

Less: accumulated depreciation account: shows the total amount of depreciation that the company has expensed so far in the asset's life.

Long-Term Investments:

Long-term investments are generally:

- Investments in shares and bonds of other companies that are normally held for many years

- non-current assets such as land or buildings that a company is not currently using in its operating activities

long-term notes receivable

long-term notes receivable

Current Assets:

Current assets are assets that a company expects to convert into cash or use within one year of its operating cycle.

Ex: cash, investments, receivables (notes receivable, accounts receivable, and interest receivable), inventories, and prepaid expenses (supplies and insurance).

The operating cycle of a company is the average time that it takes to purchase inventory, sell it on account, and then collect cash from customers.

Equity:

The content of the equity section varies with the form of business organization.

- Proprietorship, there is one capital account.

- Partnership, there is a capital account for each partner.

- Corporations often divide equity into two accounts: Share Capital—Ordinary and Retained Earnings.

Corporations record shareholders' investments in the company by debiting cash accounts and crediting the Share Capital—Ordinary account. And they combine the Share Capital—Ordinary and Retained Earnings accounts and report them in the statement of financial position as equity.

Non-Current Liabilities:

Non-current liabilities are obligations that a company expects to pay after one year.

Ex: bonds payable, mortgages payable, long-term notes payable, lease liabilities, and pension liabilities.

Current Liabilities:

Current liabilities are obligations that the company is to pay within the coming year of its operating cycle.

Ex: accounts payable, salaries and wages payable, notes payable, interest payable, and income taxes payable. We can add current maturities of long-term obligations

Current maturities of long-term obligations are payments to be made within the next year on long-term obligations.

The relationship between current assets and current liabilities:

This relationship is important in evaluating a company's liquidity (its ability to pay obligations expected to be due within the next year.)

- When current assets exceed current liabilities, the company has enough liquidity to pay the liabilities.

- When current liabilities exceed current assets, the company doesn’t have enough liquidity to pay its creditors and they might end up in bankruptcy.

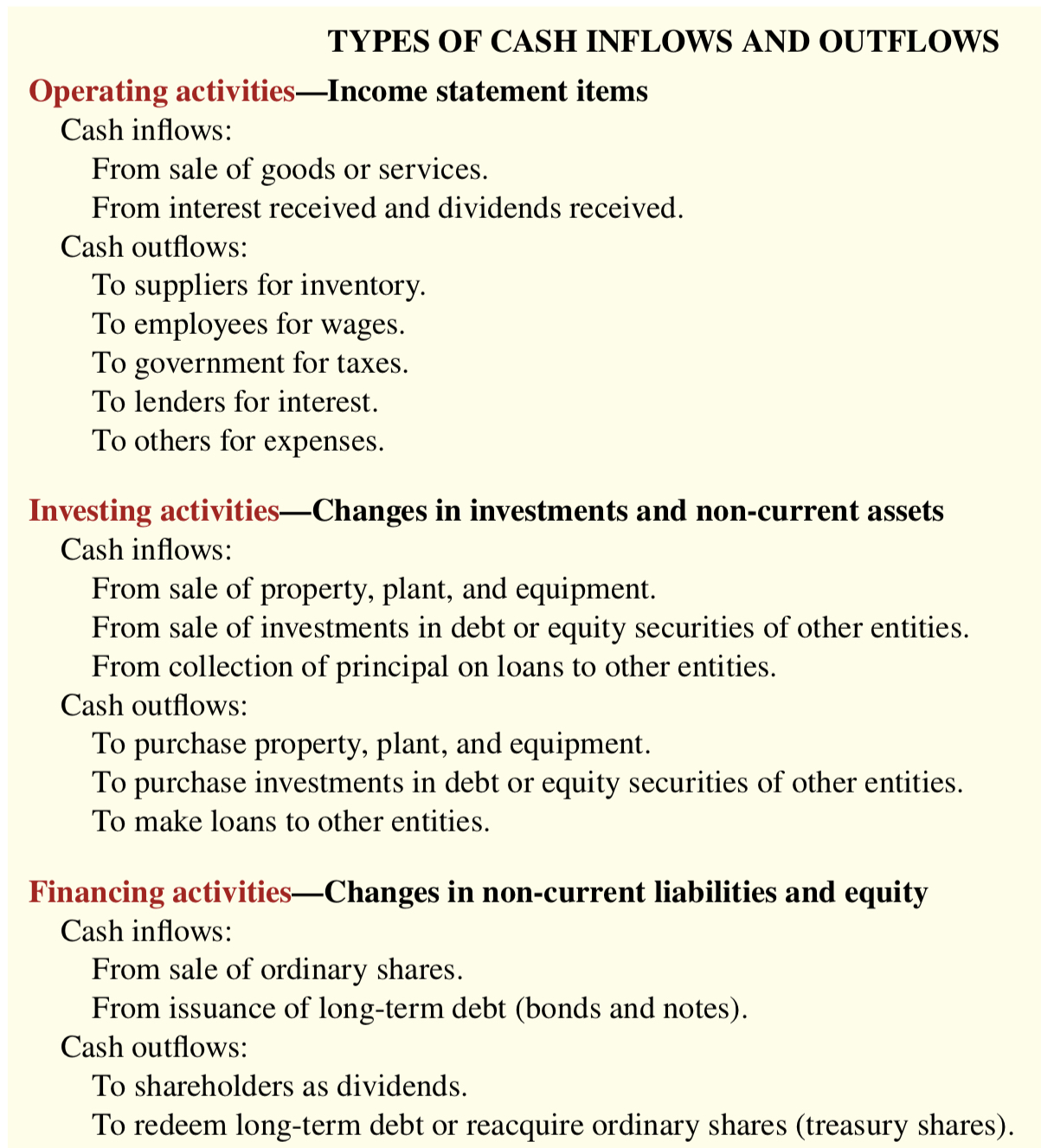

Chapter 5

Merchandising Operations and Inventory Systems:

Merchandising: companies that buy and sell merchandise (inventory) as their primary source of revenue (also known as the sale of merchandise, sales revenue or sales.)

There are 3 different types:

- Retailers à companies that purchase and sell directly to consumers

- Wholesalers à companies that sell to retailers

- Manufactures à they are the ones making the products for sale it to wholesalers

A merchandising company has 2 categories of expenses:

- Cost of goods sold: the total cost of merchandise sold during the period.

This expense is directly related to the revenue recognized from the sale of goods.

- Operating expenses: all expenses that a company will have to do in the purpose to sale inventory

Operating Cycles:

![]()

![]() The operating cycle of a merchandising company is longer than the one of a service company because a merchandising company has to purchase and kept until it’s sold to customers

The operating cycle of a merchandising company is longer than the one of a service company because a merchandising company has to purchase and kept until it’s sold to customers

Flow of Costs:

![]() The flow of costs for a merchandising company is:

The flow of costs for a merchandising company is:

As goods are sold, they are assigned to the cost of goods sold.

Ending inventory à are the good that are not sold at the end of the accounting period

Perpetual inventory system and periodic inventory system:

Companies use one of two systems to account for inventory:

A perpetual inventory system:

à Characteristic: companies keep detailed records of the cost of each inventory purchase and sale. These records show the inventory that should be on hand for every item. A company determines the cost of goods sold each time a sale occurs.

A periodic inventory system:

à Characteristic: companies do not keep detailed inventory records of the goods throughout the period. Instead, they determine the cost of goods sold only at the end of the accounting period.

At that point, the company takes a physical inventory count to determine the cost of goods on hand.

Step to determine the cost of goods sold under a periodic inventory system:

- Determine the cost of goods on hand at the beginning of the accounting period.

- Add to it the cost of goods purchased.

- Subtract the cost of goods on hand as determined by the physical inventory count at the end of the accounting period.

COGS = BB inventory + Purchases – EB Inventory

Advantages of the Perpetual System:

A perpetual inventory system is named so because the accounting records continuously show the quantity and cost of the inventory that should be on hand at any time.

This system is recommended by IFRS because it provides better control over inventories than a periodic system. (The inventory records show the quantities that should be on hand, so in case of robbery or shrinkage the company can investigate immediately.)

Recording Purchases Under a Perpetual System:

![]() Purchase Invoice: is a document that supports each credit purchase.

Purchase Invoice: is a document that supports each credit purchase.

Here, the purchaser uses a purchase invoice and a copy of the sales invoice sent by the seller. It identifies:

- Seller

- Invoice date

- Purchaser

- Sales person

- Credit terms

- Freight terms

- Goods sold: catalog number, description, quantity, price per unit

- Total invoice amount

Companies purchase inventory using cash or on account. à so they record an increase in Inventory and a decrease in Cash or account payable.

Date | Inventory Cash or account payable | x |

x |

Recording Sales Under a Perpetual System:

In accordance with the revenue recognition principle, companies record sales revenue when the performance obligation is satisfied and this happens when the goods are transferred from the seller to the buyer.

à Sales may be made on credit or for cash.

- Business documents should support every sales transaction, to provide written evidence of the sale.

- Cash Register Documents: provide evidence of cash sales

- A sales receipt is a document that provides support for a credit sale.

The original copy of the receipt goes to the customer, and the seller keeps a copy for use in recording the sale. The invoice shows the date of sale, customer name, total sales price, and other information.

The seller makes two entries for each sale.

- Records the sale: The seller increases (debits) Cash (or Accounts Receivable if a credit sale), and increases (credits) Sales Revenue.

- Records the cost of the merchandise sold: The seller increases (debits) Cost of Goods Sold, and decreases (credits) Inventory for the cost of those goods.

As a result, the Inventory account will always show the amount of inventory that the company should have.

For internal decision-making purposes, merchandising companies may use more than one sales account. On its income statement a merchandising company normally would provide only a single sales figure (so it will sum up all its individual sales accounts).

Why doing that?

- It provides detail on all its individual sales accounts by adding considerable length to its income statement.

- Second, most companies do not want their competitors to know the details of their operating results.

Chapter 6

How a company classifies its inventory depends on whether the firm is a merchandiser or a manufacturer.

- In a merchandising company, only need 1 inventory account because they sell items that have common characteristics : they are owned by the company and they are ready to be sale to customers.

- In a manufacturing company, some inventory may not yet be ready for sale. So they divide there inventory into three categories:

- Raw materials : are the basic goods that will be used in production but have not yet been placed into production.

- Work in process : are good that have been placed into the production process but is not yet complete.

- Finished goods : are good that are ready to be sold.

Companies need to make inventory to know what products are left in the company after sales. It is usually done at the end of an accouting period

When we observe the levels and changes in the levels of these three inventory types, financial statement users can gain information into management’s production plans.

Ex : low levels of raw materials and high levels of finished goods mean that there’s enough inventory on hand and production will be slowing down. High levels of raw materials and low levels of finished goods mean that the company is planning to step up production.

Many companies have significantly lowered inventory levels and costs using just-in-time (JIT) inventory methods.

With just-in-time method, companies manufacture or purchase goods only when needed.

Now we are going to focus on merchandise inventory.

Determining Inventory Quantities :

It doesn’t matter whether we are using a periodic or perpetual inventory system, all companies need to determine inventory quantities at the end of the accounting period.

If we are using a perpetual inventory system, companies take a physical inventory because they need :

1. To check the accuracy of their perpetual inventory records.

2. To determine the amount of inventory lost due to wasted raw materials, shoplifting, or employee theft.

If a companies is using a periodic inventory system they will take a physical inventory for two different purposes:

- To determine the inventory on hand at the statement of financial position date

- To determine the cost of goods sold for the period.

Determining inventory quantities involves two steps:

- Taking a physical inventory of goods on hand

- Determining the ownership of goods.

Taking a Physical Inventory

Taking a physical inventory involves actually counting, weighing, or measuring each kind of inventory on hand. An inventory count is generally more accurate when goods are not being sold or received during the counting. Consequently, companies often “take inventory” when the business is closed or when business is slow. This is why many retailers close early 1 day in January ( after the holiday sales and returns, because inventories are at their lowest level) to count.

Determining Ownership of Goods

One challenge in counting inventory quantities is determining what inventory a company owns.

To determine ownership of goods, two questions must be answered:

- Do all of the goods included in the count belong to the company?

- Does the company own any goods that were not included in the count?

Goods in Transit :

A difficulty in determining ownership is goods in transit at the end of the period. The company may have purchased goods that have not yet been received, or it may have sold goods that have not yet been delivered.

To arrive at an accurate count, the company must determine ownership of these goods.

Goods in transit should be included in the inventory of the company that has legal title to the goods.

When the terms are FOB (free on board) shipping point, ownership of the goods passes to the buyer when the public carrier accepts the goods from the seller.

Ex : You purchase goods from a seller in Los Angeles with the agreement FOB Shipping Point terms for the transaction (you need to ship it to NewYork). The seller will prepares the goods for shipment in Los Angeles. Once the goods are handed over to the carrier in Los Angeles, ownership of the goods transfers from the seller to you, the buyer. From this moment as the buyer, you are responsible for the transportation costs, insurance, and any risks associated with the goods during transit from Los Angeles to New York. The goods are shipped to New York, and when it arrive as the buyer, you take possession of the goods.

When the terms are FOB destination, ownership of the goods remains with the seller until the goods reach the buyer.

Ex : You and the seller agree to FOB Destination terms for the transaction ( to ship in NewYork) and he seller prepares the goods for shipment in Los Angeles. Unlike FOB Shipping Point, in FOB Destination, ownership of the goods remains with the seller until the goods reach the destination. The seller is responsible for the transportation costs, insurance, and risks associated with the goods during transit from Los Angeles to New York. The goods are shipped to New York, and ownership of the good is transferred to the buyer only when the good arrived to the destination.

If goods in transit at the statement date are ignored, inventory quantities may be seriously miscounted.

Consigned Goods.

Consigned goods: is when someone will keep and sell the good of another business for them for a fee. The parti how does that don’t have an ownership on the good —> CCL the good must not be added in the inventory of the company who sell the good for the other company because they don’t own it. Normally when a company want another parti to sell a good for them is beause :

. they when to keep their inventory cost low

. they believe that they won’t be able to sell it themselves

Ex: You and Sarah agree that she will provide her handmade jewelry to your boutique for display and sale. Despite the goods being physically in your boutique, Sarah, as the ownership of the jewelry. Your boutique has Sarah's jewelry, and customers can purchase them directly from your store. When a customer buys a piece of jewelry, your boutique handles the sale, but you don't own the items. Instead, you and Sarah have agreed on a revenue-sharing arrangement or a fee for each item sold. If some jewelry items remain unsold after a certain period, you might return them to Sarah, or you could both agree on a plan for handling unsold items.

Inventory Methods and Financial Effects:

Inventory is accounted as a cost.

When we say « Cost », it includes everything that is necessary to acquire a goods and place them in a condition ready for sale (every modification done to a good to put them in sell is considers as cost of inventory ).

Ex: You purchase flour, sugar, eggs, and other ingredients to make the cupcakes. The cost of these raw materials is considered part of the inventory. The time and effort spent by the baker in mixing the ingredients, baking the cupcakes, and decorating them are considered as labor costs. These costs are also the inventory costs. the electricity used by the ovens, the cost of packaging materials, and a portion of the rent for the bakery space, are costs associated with the production of the cupcakes. These costs are included in the inventory. If you need to transport the cupcakes to a retail location, any transportation costs incurred, such as fuel or shipping fees, are considered part of the inventory cost. The cost of storing the cupcakes in a refrigerated display or storage area, including rent for that space, contributes to the overall inventory cost.

After a company has determined the quantity of units of inventory, it applies unit costs to the quantities to find the total cost of the inventory and the cost of goods sold.

But the problem is that in your inventory you ight have purchasesd the good at different prices and at different time cause your accounts to be miscounted

(Cost of goods sold will differ depending on which two prices the company sold.)

If a company can easily identify which particular units it sold and which are still in ending inventory, it can use the specific identification method of inventory costing. Using this method, companies can accurately determine ending inventory and cost of goods sold.

If a company uses specific identification it requires

- that companies keep records of the original cost of each individual inventory item.

Ex: Imagine you run a small antique shop, and you have three unique items for sale:

- Typewriter: Purchased for $200

- Record Player: Purchased for $150

- Rare Book: Purchased for $300

- A customer comes in and buys the typewriter. In a specific identification system, you would record the sale using the actual cost of the typewriter, which is $200.

- Another customer purchases the vintage record player. You would record this sale using the cost of the record player, which is $150.

- The rare book is still in your inventory.

Historically, this method was possible only when a company sold a limited variety of high-unit-cost items that could be identified clearly from the time of purchase through the time of sale. Ex of products which we can still use the method: cars, pianos, or expensive antiques.

Today, this practice is still relatively rare. Instead, rather than keep track of the cost of each particular item sold, most companies make assumptions, called cost flow assumptions.

Cost Flow Assumptions :

This technique can be used when we sell a large amount of identical unis to track the cost of good flow

There are three assumed cost flow methods but we will only use two because they are permitted be IFRS :

1. First-in, first-out (FIFO)

2. Average-cost

3. Last in first out (LIFO)—> used by GAAP

To demonstrate the two cost flow methods, we will use a periodic inventory system. We assume a periodic system because very few companies use perpetual FIFO or average-cost to cost their inventory and related cost of goods sold.

Companies that use perpetual systems often use an assumed cost (called a standard cost) to record cost of goods sold at the time of sale. Then, at the end of the period when they count their inventory, they will have to recalculate cost of goods sold using periodic FIFO or average-cost

First-In, First-Out (FIFO) :

The first-in, first-out (FIFO) method assumes that the earliest goods purchased are the first to be sold. Here, the costs of the earliest goods purchased are the first to be recognized in determining cost of goods sold. It does not necessarily mean that the oldest units are sold first, but that the costs of the oldest units are recognized first.

Under FIFO, since it is assumed that the first goods purchased were the first goods sold, ending inventory is based on the prices of the most recent units purchased. That is, under FIFO, companies obtain the cost of the ending inventory by taking the unit cost of the most recent purchase and working backward until all units of inventory have been costed.

FIFO (First-In, First-Out): FIFO assumes that the oldest inventory items (first to be purchased or produced) are the first to be used or sold.

Ex: Most of the books Bookmarker sells are bought from publishers. The price of these books is set by the publisher and this price can change based on the popularity of the book, printing costs, number of books bought, etcetera. During 2020, the following transactions have occurred for a book. Assume that Bookmarker uses a perpetual inventory system. The owner can easily calculate total sales revenue for this title, because he knows that 45 books were

![]() sold during 2020 at a price of €20 per copy, but he is not sure what number he has to use for the cost of goods sold. He knows this number depends on the assumed cost flow method FIFO, Average-cost, and LIFO. Let’s follow the FIFO method

sold during 2020 at a price of €20 per copy, but he is not sure what number he has to use for the cost of goods sold. He knows this number depends on the assumed cost flow method FIFO, Average-cost, and LIFO. Let’s follow the FIFO method

Total inventory before sales : 30+ 10+10+10= 60

Unite of inventory sold : 45

Inventory left : 15 (ending inventory)

|

| The cost of the purchase |

Beginning inventory | 30*8 | 240 |

Feb 5 : Purchased | 10*10 | 100 |

July 12 : Purchased | (15-10)*11–>5*11 | 55 |

| 45 | COGS : 395 |

Ending inventory | 10*12+ 5*11 | 175 |

Average-Cost

![]() When we use the average-cost method we have to take the average of what we have brought during the accouting period and use it to identitfy the cost of good sold and the value of the inventory.

When we use the average-cost method we have to take the average of what we have brought during the accouting period and use it to identitfy the cost of good sold and the value of the inventory.

Average Cost: The average cost method assigns a cost based on the average price of all units in inventory. This method evens out the cost of goods sold and provides a middle-ground approach between FIFO and LIFO during fluctuating prices.

EX: At the beginning of the month, the store has 200 packs of pens from the previous month, which were purchased at $1.50 each.

- Throughout the month, the store makes two additional purchases:

- Purchase 1: 100 packs of pens at $1.60 each

- Purchase 2: 150 packs of pens at $1.70 each

- The store makes various sales throughout the month but doesn't immediately reduce the inventory. Instead, it keeps a record of the sales. At the end of the month, the store physically counts its remaining inventory and determines the cost of goods sold (COGS) using the average cost method.

- Calculation of Average Cost:

- The average cost per unit is calculated by taking the weighted average of the costs for the available inventory.

![]() If the store sells 300 packs of pens during the month, it uses the average cost of $1.59 to calculate the cost of goods sold.

If the store sells 300 packs of pens during the month, it uses the average cost of $1.59 to calculate the cost of goods sold.

COGS = 300 × $1.59

COGS ≈ $ 477

The ending inventory is the remaining unsold packs of pens, valued at the average cost.

Ending Inventory=(200+100+150)−300

Ending Inventory = 450 − 300

Ending Inventory = 150 packs

LIFO Inventory Method:

LIFO (Last-In, First-Out): LIFO assumes that the newest inventory items (last to be purchased or produced) are the first to be used or sold. This method often results in higher costs of goods sold and lower ending inventory when prices are rising. Under IFRS, LIFO is not permitted for financial reporting purposes. LIFO is used for financial reporting in the United States, and it is permitted for tax purposes in some countries. Its use can result in significant tax savings in a period of rising prices. Under the LIFO method, the costs of the latest goods purchased are the first to be recognized in determining cost of goods sold.

Financial Statement and Tax Effects of Cost Flow Methods

A recent survey of IFRS companies indicated that approximately 60% of these companies use the average-cost method, with 40% using FIFO. In fact, approximately 23% use both average-cost and FIFO for different parts of their inventory.

The reasons companies adopt different inventory cost flow methods are varied, but we can count 3 main ones

1. income statement effects

2. statement of financial position effects

3. tax effects.

Income Statement Effects:

To understand why companies choose either FIFO or average-cost, let’s examine the effects of these two cost flow assumptions on the income statements

Note the cost of goods available for sale (HK$12,000) is the same under both FIFO and average-cost. However, the ending inventories and the costs of goods sold are different. This difference is due to the unit costs that the company allocated to cost of goods sold and to end- ing inventory. Each dollar of difference in ending inventory results in a corresponding dollar difference in income before income taxes.

In periods of changing prices, the cost flow assumption can have a significant impact on income and on evaluations based on income, such as the following.

- If prices rises , FIFO will reports a higher net income than average-cost because using Fifo we are taking the first purchases (= less expensive purchase) the cost of good sold will be lower and since I leave my ending inventory with my last purchase (= most expensive purchase) it will be higher. if my cost of good sold is low my net income is high

2. If prices are falling, FIFO will report the lower net income and average-cost the higher because using Fifo we are taking the high purchases (= most expensive purchase) the cost of good sold will be higher and since I leave my ending inventory with my last purchase (= less expensive purchase) it will be lower. if my cost of good sold is high my net income is low

CCL: companies tend to prefer FIFO because it results in higher net income because external users view the company more favorably and , managers will receive bonuses if the net income is higher.

Statement of Financial Position Effects :

A major advantage of the FIFO method is that in a period of rising prises, the costs allocated to ending inventory will close to their current cost.

Ex: Imagine you have a stack of boxes, and you keep adding new boxes on top. When you sell something, you take from the top (the oldest boxes). In a period of rising price, using FIFO is like selling the older items first. This means the cost you assign to your ending inventory (what's left unsold) is closer to the current, higher prices.

The average-cost method is that in a period of rising prices, the costs allocated to ending inventory may be understated in terms of current cost. The understatement becomes greater over prolonged periods of inflation if the inventory includes goods purchased in one or more prior accounting periods.

Ex: Imagine you have a mix of old and new boxes, and you calculate an average cost for everything. When you sell something, you use this average cost. In a period of rising price, this average might be lower than the current prices, especially if you have older, cheaper items in your inventory.

The showcase of the average cost method : With the average-cost method, as prices go up, your calculated average might not keep up. If you have goods from previous periods( when prices were lower) , the cost assigned to your ending inventory might be lower than what it would cost to replace those items with new ones. This could lead to understating the value of your unsold items.

Tax Effects :

We as we can see in the statement of financial position and net income on the income statement are higher when companies use FIFO in a period of inflation. But, some companies use average-cost.

Why? The average-cost cause a lower income taxes (because of lower net income) during times of rising prices. ( if your net income is low the government will taxe you less in it—> you pay less taxes )

Using Inventory Cost Flow Methods Consistently :

The consistency concept: it means that a company uses the same accounting principles and methods from year to year. So watch ever cost flow method a company chooses, it should use that method consistently from one accounting period to another. They do this to facilitates the comparability of financial statements over successive time periods. It does not mean that a company cannot change its inventory costing method. When a company adopts a different method, it should specify in the financial statements the change and its effects on net income.

Effects of Inventory Errors :

Unfortunately, errors occasionally occur in accounting for inventory. In some cases, errors are caused by :

- Failure to count

- Price the inventory correctly

- When companies do not properly recognize the transfer of legal title to goods that are in transit.

When errors occur, they affect both the income statement and the statement of financial position.

Income Statement Effects :

![]() The ending inventory of one period becomes the beginning inventory of the next period. So if there’s an inventory errors it can affect the calculation of cost of goods sold and net income in two periods.

The ending inventory of one period becomes the beginning inventory of the next period. So if there’s an inventory errors it can affect the calculation of cost of goods sold and net income in two periods.

![]()

Remember:

An error in the ending inventory of the current period will have a reverse effect on net income of the next accounting period. Note that the understatement of ending inventory in 2019 results in an understatement of beginning inventory in 2020 and an overstatement of net income in 2020.

![]()

![]()

Over the two years, though, total net income is correct because the errors réajustée itself. The correctness of the ending inventory depends entirely on the accuracy of taking and costing the inventory at the statement of financial position date under the periodic inventory system

Statement of Financial Position Effects:

![]() The ending inventory errors can effect the statement of financial position by using the basic accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.