D2- Life history trade-offs

Trade-offs (and constraints) in organismal biology, Theodore Garland Jr et al., 2022

Abstract-

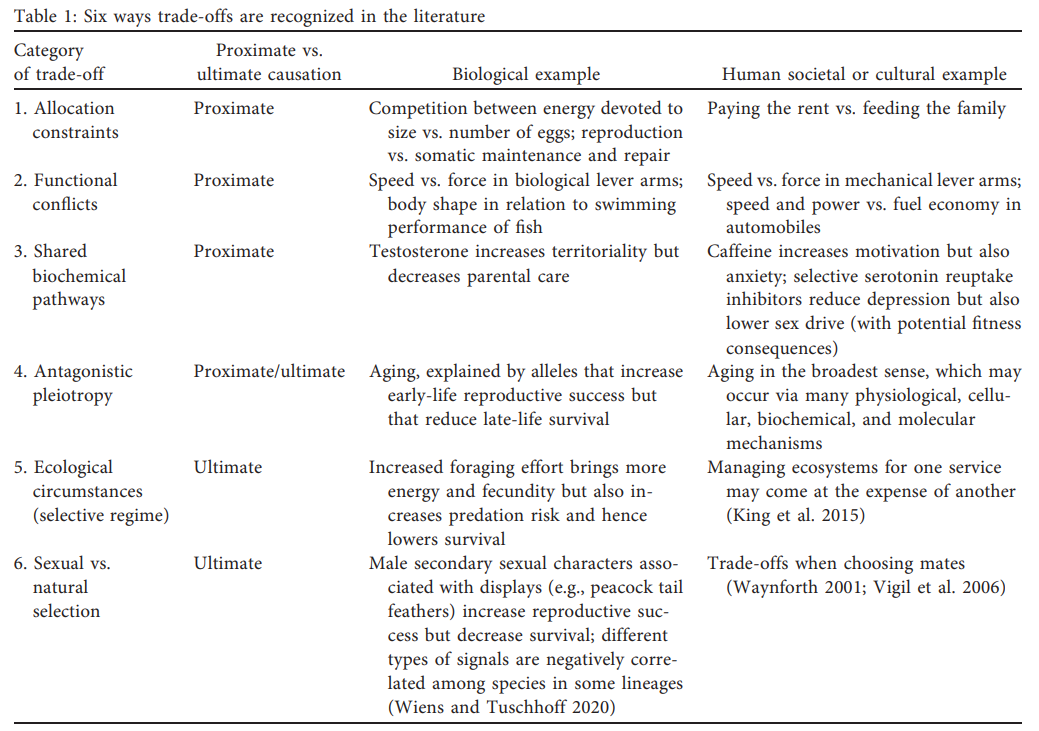

Trade-offs can be defined, categorized, and studied in at least six, not mutually exclusive, ways.

trade-offs only happen when there are low resources or phenotypic extremes

Introduction-

aim→ outline a general framework for relating the concepts of trade-offs and constraints in biology, with an emphasis on the perspectives of organismal biology

some trade offs arise from simple pathways whilst others are complex

bought together different research methods- get a broad perspective as trade-offs happen at all levels e.g. organismal, population, trade-offs occur as networks of interacting processes, where, for example, the trade-off between A versus B might depend on the resolution of a prior trade-off between A1 and A2 upstream in a network that culminates in A. the mechanisms and selective pressure span many disciplines for many trade-offs→ trade-offs aren’t simple

What Are Trade-Offs and Constraints?

trade offs→ the mechanistic processes that cause one trait to decrease when another increases, cannot increase without a decrease not will not, is a cause not a consequence

constraint has many definitions in different aspects

a trade-off involves a constraint placed simultaneously on the functional relationship between two (or more) traits.

When only two such competing functions are involved, this is termed the Y-model e.g. size vs number of offspring

will only be a trade off if the total amount of resources is being used up

Six Categories of Trade-Offs:

allocation constraints→ a limit exists for the total amount of a resource that is available, lead to trade-offs in traits, For a given resource, multiple hierarchically arranged Y model constraints often exist.

strategies are to have trade-offs in other traits or phenotypic plasticity

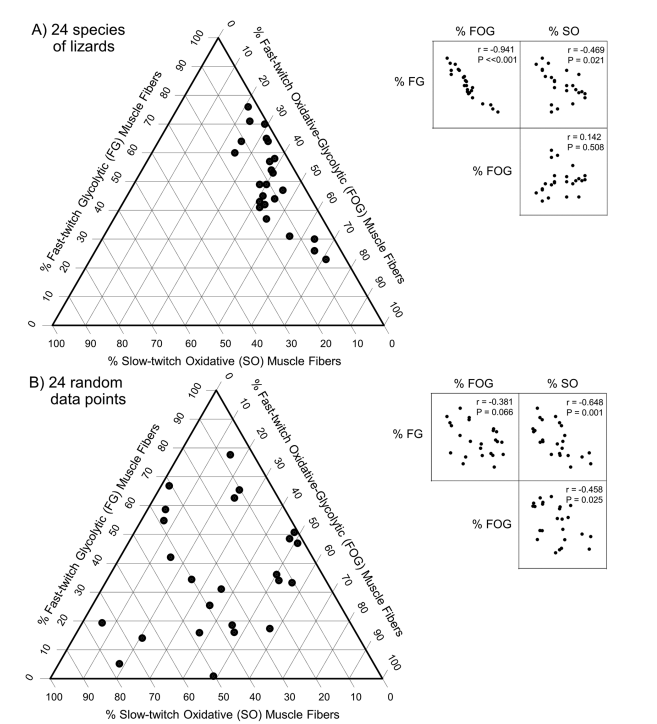

should be careful as just because the muscles will add up to 1 doesn’t mean there is a correlation e.g. random points also show a trade-off just because they add up to 1

functional constraints→ a feature that enhances one trait decreases the performance of another

examples

shared biochemical pathways→ often involve integrator molecules (e.g., hormones, neurotransmitters, transcription factors) that simultaneously affect multiple traits, with some effects being beneficial for one or more components of Darwinian fitness (e.g., survival, age at first reproduction, fecundity) and others detrimental

e.g. concentrations of testosterone: high levels can increase growth rate, muscle mass, bone density, activity levels, and territorial/aggressive behavior but also increase parasitism and decrease paternal care

e.g. caffeine increases motivation and performance in both mental and physical tasks but also increases heart rate and anxiety and can disrupt sleep

Recently, trade-offs involving integrator molecules have been placed within a network framework→ insights about the connected nature of physiological traits and insights about how molecules that mechanistically regulate a trade-off can also trigger other physiological responses that help mitigate that same trade-off

Antagonistic pleiotropy describes genetic variants that increase one component of Darwinian fitness simultaneously decrease another, causing a negative additive genetic correlation between the two components. → a single locus affects two or more apparently unrelated phenotypic traits

pleiotropy occurs not magically but via ordinary biochemical pathways and physiological mechanisms, including integrator molecules, and in the context of ecological circumstances and whatever sexual selection may be occurring

e.g. This theory of aging posits that alleles increasing components of early-life reproductive success (e.g., age at first reproduction) may reduce late-life survival,

ecological circumstances→ external context of trade-offs. Many trade-offs are driven by ecological circumstances and when the relationship between traits and Darwinian fitness varies with environmental conditions, they will be context dependent. when trade offs occur that are context dependent. there is a trade-off and there are mechanisms due to this but the ecological circumstances weight the alternatives that must be traded off by setting the selective regime under which the mechanisms will occur

Sexual selection→ may lead to the elaboration of (usually male) secondary sexual characters that improve mating success but handicap survival and/or impose energetic costs that reduce other fitness components.

immunohandicap hypothesis→ females prefer males that can maintain ornamental secondary sex characteristics in the face of parasites→ keeps the trait honest

mechanistic hypothesis→ androgens have the dual role of increasing expression of sexual ornaments while suppressing immune function (Owens and Short 1995). It follows that males can have ornamental characteristics and fight parasite infections only if they are of high quality.

Some Examples of Why Trade-Offs Matter:

maintains genetic diversity e.g. pea aphids

lead to variation in a trait e.g. bill depth in darwin’s finches

makes sure there is not one superspecies

Proximate versus Ultimate Causation: Mechanism versus Evolution

Proximate causation refers to immediate mechanisms of a biological trait. For trade-offs, proximate causes include resource limitations leading to allocation constraints, functional conflicts, and shared biochemical pathways→ associate proximate causes with processes that occur within an organism’s lifetime, observed in one generation

Ultimate causation refers to the evolutionary processes that shape a biological trait, including ecological circumstances that cause variation in selection regimes, sexual selection and other evolutionary mechanisms (e.g., founder effects, genetic drift)→ processes that involve Darwinian selection that spans generations, observed among many generation

e.g. Mice with mutations in TP53 that enhance activity of its associated pathway have fewer spontaneous tumors compared with wild-type littermates, but these mice also exhibit early onset of phenotypes associated with aging. At the proximate level over an individual’s lifetime, this demonstrates a trade-off between aging and incidences of cancer that are mediated by the pleiotropic effects of TP53. At the ultimate level of human evolution, this also suggests the reason natural selection cannot simply act to increase activity of TP53 to reduce cancer risk: doing so would reduce longevity.

Proximate Causes of Trade-Offs:

internal factors causing trade-offs

e.g. integrator molecules

Physiological Regulatory Networks

They consist of a network of signaling molecules grouped into subnetworks, and each subnetwork regulates a particular set of physiological processes with connections

e.g. In insects, the stress response and immune response networks share some signaling molecules, including octopamine and adipokinetic hormone. These hormones are released during a fight or-flight stress response and its corresponding intense physical activity and facilitate trade-offs with components of the immune system.

not all interactions mediated by integrator molecules cause trade-offs and that the outcome will depend on the species, the internal and external contexts, and the pathway involved, highlighting the need to investigate the mechanism underpinning trade-offs rather than relying on measuring negative correlations

It follows that integrator molecules can help ameliorate the effects of a trade-off as well as cause a trade-off

explains why suites of physiological traits and their associated trade-offs change in tandem e.g. wake/sleep

Integrator Molecules and Trade-Offs: Examples Involving Immune Defenses

Timescales and Trade-Off Compensation

trade offs can be different lengths and varies between species

is useful to know the timings of trade offs because it informs the biological scale at which consequences of the trade-off occur

Acute changes driven by resource limitations are going to have organism-level consequences, whereas trade-offs that are maintained across generations have consequences for ecological community function and hence underpin evolutionary patterns that are driven by tradeoff

look at e how trade-offs are organized along a temporal scale, from acute to microevolutionary, and how the duration of a trade-off relates to the scale of the consequences and the compensation strategies employed.

Acute Trade-Offs

shorter than lifetime

alter behaviour→ can lead to trade offs

are condition dependent, facultative

Chronic Trade-Offs

can be adaptive e.g. predictive like favouring reproduction over foraging, or a response to a chronic condition- will disappear after condition has disappeared

plasticity

Developmental Trade-Offs

early in life or at crucial points, have long-lasting sometimes irreversible effects

These trade-offs can arise because a signal during a critical developmental window leads to irreversible change to a phenotype; this type of phenotypic plasticity is known as developmental plasticity

Transgenerational Effects

factors generating trade off are passed down

plasticity by parents alters further generations

Microevolutionary Trade-Offs

genetic variation in populations, persist across generations

need generational solutions like speciation, mutations

caused by internal, proximate mechanisms, including (i) linkage disequilibrium between two or more loci and (ii) pleiotropic gene action

Network Perspectives on Trade-Offs

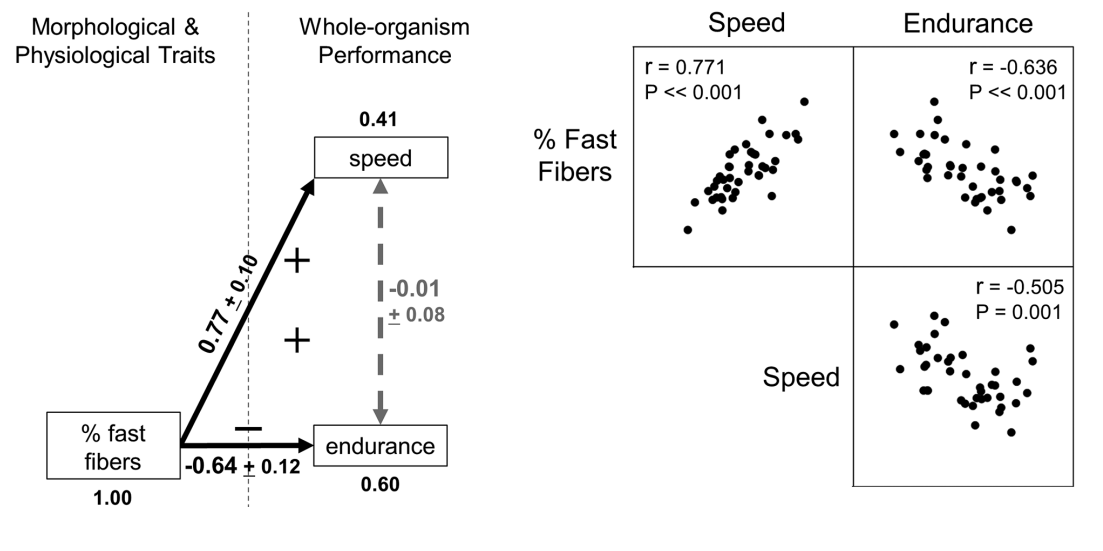

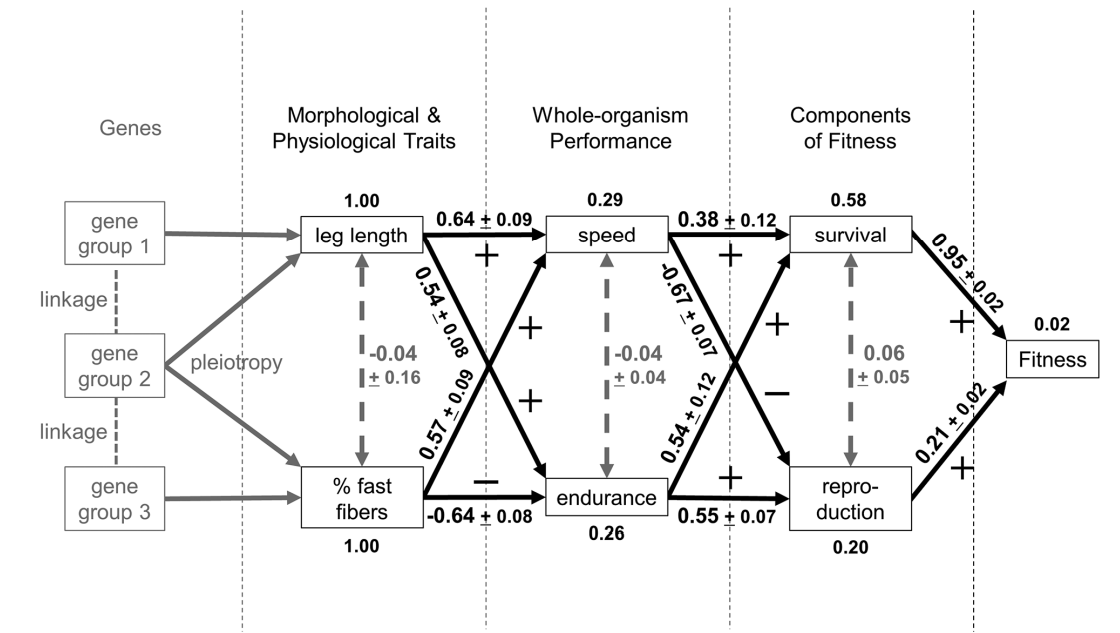

main goals in this article is to champion the need for a broad view of trade-offs to encompass simultaneously both multiple proximate mechanisms and ultimate drivers of evolution. Here, we illustrate the complexities that emerge in networks of trade-offs using an explicit numerical model related to locomotor performance.

Simple Binary Trade-Offs

The focus in the literature on binary trade-offs can lead researchers to miss important trade-offs or to misinterpret the nature of a trade-off. sometimes refer to a negative relationship between two traits simply as a trade-off, keeping in mind that it is actually the result of a trade-off

A Trade-Off Network of Seven Traits

many more lower-level traits affect muscle function and running endurance capacity, including hormones and probably signals from the central nervous system

Analysis of the Entire Network

Relationships at higher levels of biological organization may be very difficult to predict from those involving lower-level traits because of the detail of information that is needed

Analysis of Subsets of the Network

different biologists look at different subsets of networks

→ to fully understand the role of trade-offs in the functioning and fitness of organisms, we need to integrate across disciplines and explore trade-offs in the context of causal networks rooted in mechanism. A corollary is that multiple types of trade-offs generated by different biological processes must be considered. Another corollary is that unexpected functional properties may emerge even from relatively simple systems

How to Study Trade-Offs (and Constraints)

empirical studies often search for negative correlations between two traits. negatives→ Failing to include traits that play a key role in a particular trade-off is another common problem in empirical studies. Moreover, tradeoffs often occur only at the extremes of distributions, as in animals that have exceptional athletic abilities or live in extreme environments, Therefore, the choice of individuals, populations, or species to study can have a large effect on the ability and statistical power to detect trade-offs, As the number of traits involved increases, using negative (genetic) correlations to identify trade-offs becomes more problematic

incomplete sampling of the organisms in question, including a failure to consider extinct forms that may have been different in body size

Comparative Studies

comparing species

constraints can also be recognized in comparative data where they appear as a limit to the range of a given phenotype or by a gap in phenotypic space

Individual Variation

Physiological Correlations and Manipulations

controversy on the value of physiological manipulations for elucidating evolutionary trade-offs

Physical Models

aerodynamics in vehicles→ link it to understanding the evolution of gliding behavior and flight and how body size, body plan, and body shape may affect flight performance

Genetic Correlations

used to predict the rate and direction of evolutionary changes

Selection in the Wild

ecological circumstances that might cause trade-offs are of interest, then studies of selection in the wild are the method of choice

observational or can involve experiments, such as field introductions or transplants , or modification of the characteristics of individual organisms

Selection Experiments

Selection experiments and experimental evolution in both laboratory and field settings

Correlated responses to selection indicate genetic correlations, many of which will represent functional relationships among traits, including trade-offs and constraints

These selection studies show the power of manipulating the “ecological” circumstances of populations in ways that are explicitly designed to reveal trade-offs at the mechanistic level. As such, they make it possible to understand how the integration of multiple trade-offs determines the evolutionary trajectories of populations.

Theoretical Models

mathematic formulations and computer simulations

Optimality models based on costs versus benefits are commonly used, and all of them assume some sort of constraint (limit) that causes a trade-off

Finally,we see a need for models that explicitly include genetics and mechanistic networks of physiological and morphological traits, all under natural selection, in order to better understand how patterns of trait correlations emerge in real populations and how we can find them in real data.

the need to measure mechanisms of trade-offs to distinguish trade-offs from observed negative correlations. scientists with different perspectives talk to each other about trade-offs and thus improve our understanding of both how organisms work and how they evolve.

Predicting Life-History Trade-Offs with Whole-Organism Performance, Simon Lailvaux and Jerry Husak, 2017

Introduction-

main principle of life history theory is that allocation to a fitness-enhancing trait depends on the amount of resources acquired, limited resource pools therefore drive trade-offs between traits

trade-offs means traits can be constrained, reduced or checked entirely

know about trade offs in traditional phenotype traits e.g. gestation period, age of sexual maturity, longevity but not trade-offs in whole-organism performance traits e.g. running, biting, flying, affect survival through dispersal, predator-prey interactions, foraging and also reproductive success in males through combat

previous studies→ expression of performance traits is traded-off with other traits that are important for energy expenditure e.g. experimentally activating the immune system reduced speed by 13% in 4 hours in lizards, forcing lizards to invest in locomotor endurance on treadmills increased their endurance but also in other traits too

dietary restriction- exposes trade-offs as expression is more apparent when there are less energetic resources

ecological cost of transport definition→ the percentage of that species’ daily energetic expenditure that is accounted for by the energetic costs of movement→ useful metric of the cost of locomotor performance

existing data- carnivores have the highest, non-carnivores have lower

ECT is still useful in testing for trade-offs

energy budgets vary between individuals and between age, sex, and season

Costs of reproduction are also variable, but tend to be especially high for female eutherian mammals, primarily driven by the energetic requirements of lactation- a given bout of reproduction increases metabolic rates overall by around 25%, with the majority of that increase (80%) being attributable to lactation alone

pregnancy and lactation require very high rates of metabolism, and consequently a high basal rate of metabolism facilitates a high reproductive output. These high costs of reproduction require that animals either time their reproductive output to coincide with periods of high environmental resource availability, or allocate existing resources away from other physiological tasks and toward reproduction.

hypothesis tested→ that locomotor performance and reproduction, which use a large amount of energy budget, trade off against each other

more expensive traits will prompt trade off to a larger extent than cheaper traits

whether a trait is expensive depends on the amount of resources available and also the baseline rate of energetic expenditure which is different for each organism

to work this out, need to know the average energetic cost of using a trait out of the total daily energetic costs

use GPS and remote-sensing technology for this

e.g. used SMART tracking in lions, showed use 10-20% of energy costs on locating prey

predict→ mammal species that spend a large proportion of their daily energy budgets on locomotion (high ECTs) exhibit lower reproductive outputs, therefore slower life histories

locomotion was quantified by ECT- what is ECT? expresses the daily cost of locomotion as a percentage of total daily energetic expenditure,

aim→ to test for a trade-off between locomotor performance and a suite of life history traits, which collectively represent the slow fast life-history continuum, create a framework that predicts the circumstances that performance traits will trade-off with other life-history traits, and in which species

what do we mean by energetic resources?

Materials and Methods-

collected life-history data (gestation length, lifespan, age at weaning, age at female reproductive maturity, and litter size) and data on daily movement distance, incremental cost of locomotion and daily energetic expenditure, as well as mass from the literature for a total of 72 mammal species→ calculate ECT

included basal metabolic rate (BMR) as a predictor variable in the current analysis. Relevant data on BMR for the taxa of interest are even sparser than the life-history data.

The phylogeny and branch lengths used were derived from a recent comprehensive mammalian phylogeny by BinindaEmonds et al. (2007). We therefore log-transformed all life-history data prior to analyses (as in Swanson and Dantzer 2014).

comparative analysis

Results-

prediction was supported by analysis of life history and ECT across several mammalian orders

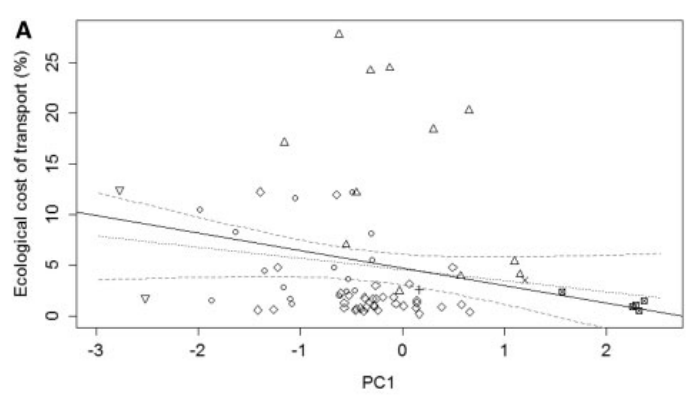

a significant negative relationship between ECT and the major multivariate life-history axis (PC1; Fig. 1) which corresponds to the slow-fast life histories→ species with high scores on PC1 (those with high reproductive outputs, but small body size and metabolic rate, and short lifespan) invest heavily in reproduction but spend less energy on a day-to-day basis on locomotion→ support for a potential trade-off between performance and reproductive investment as represented by overall life-history strategy.

Discussion-

one explanation for smaller species showing this is the central limitation hypothesis→ small mammals such as rodents are limited in the rate at which they can acquire resources by their limited food intake e.g. female mice killed their offspring rather than eating more when forced to run on wheels through the first 12 days of lactation to pay for the extra locomotor expense

→ smaller mammals may be especially prone to life history trade-offs with reproduction not necessarily (or not only) because of their relatively high costs of reproduction, but because of their relatively limited food intake/nutrient uptake rates

did not get results on the timing of those costs and trade-offs, nor into the potential intraspecific variation in those costs→ important impact on overall fitness, implies that trade-offs between whole-organism performance capacities and other life-history traits will not only depend on the energetic costs of both the performance trait and of other traits involved in that trade-off, but they may also be realized only at certain times of year, and more readily in one sex or the other, usually females

future→ test whether the costs paid specifically by females, for example, constrain male locomotor investment sufficiently to be manifest at the species level, or if intersexual variation in life-history strategy leads to variation in patterns of trade-offs as well.

Q- how could we do that?

Positives and negatives of the study:

+

- had to predict quite a lot of their data as it was not available especially daily energy expenditure, could not do it on other taxa- only mammals, reduces sample size and power, interpolate missing datapoints for the current dataset based on body mass as well based on existing equations for scaling of mammalian life history variables, whether the costs paid specifically by females, for example, constrain male locomotor investment sufficiently to be manifest at the species level, or if intersexual variation in life-history strategy leads to variation in patterns of trade-offs as well, individual heterogeneity