Unit 3: Complex Rhetorical Modes

Process Analysis

Process analysis is a rhetorical mode that’s used by writers when they want to explain either how to do something or how something was done.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

Process analysis can be an effective way of relating an experience.

Take, for example, this excerpt from “On Dumpster Diving” from Travels with Lizbeth by Lars Eighner.

This is a good illustration of writing process analysis.

Although the content is ordered chronologically, the author adds explanatory examples and personal commentary to liven up the segment.

In this section, the author is outlining the psychological progression of a homeless scavenger based on his personal experience and exposing the excesses of a consumerist culture.

When and How to Use Process Analysis

- Sequence is chronological and usually fixed—think of recipes.

- When you use this device, make sure the stages of the process are clear, by using transitions (e.g., first, next, after two days, finally).

- Make sure your terminology is appropriate for the reader.

- Verify that every step is clear; an error or omission in an intermediate step may make the rest of the process analysis very confusing.

Cause and Effect

Cause and effect explains the processes responsible for the process.

Some cause-and-effect relationships are easy to describe.

For example:

In this passage, Pangloss is using a series of cause-and-effect relationships to prove his point, that “things cannot be otherwise than as they are.” You see examples of this rhetorical mode all around you.

When and How to Use Cause and Effect

- Do not confuse the relating of mere circumstances with a cause-and- effect relationship.

- Turn your causal relationships into causes and effects by using carefully chosen examples.

- Make sure to carefully address each step in a series of causal relationships; if you don’t, you risk losing your reader.

Definition

You are probably familiar with definitions; you see them every time you look up a word in the dictionary.

Hopefully when you write, you try to make sure your reader understands the words that you use.

Here, for example, is a paragraph that defines feis (pronounced “fesh”).

The text begins with a simple definition, but the definition is elaborated and rhetorical forms are blended.

You probably noticed the comparison to a soccer match, and then there is an ill-conceived (imperfectly formed) attempt at categorisation (the divisions in the competition).

You can even contend that using Lord of the Dance as an example is appropriate.

The rhetorical form of definition can be used to explain a word or concept, but authors usually employ it to engage readers.

When and How to Use Definition

- Keep your reason for defining something in mind as you’re writing.

- Define key terms according to what you know of your audience, in other words, the readers of the essays; you don’t want to bore your reader by defining terms unnecessarily, nor do you want to perplex your reader by failing to define terms that may be obscure to your audience.

- Explain the background (history) when it is relevant to your definition.

- Define by negation when appropriate.

- Combine definition with any number of other rhetorical modes when applicable.

Description

Description can help make expository or argumentative writing lively and interesting and hold the reader’s interest, which is vital, of course.

Oftentimes description serves as the primary rhetorical mode for an entire essay—or even an entire book.

It’s typically used to communicate a scene, a specific place, or a person to the reader.

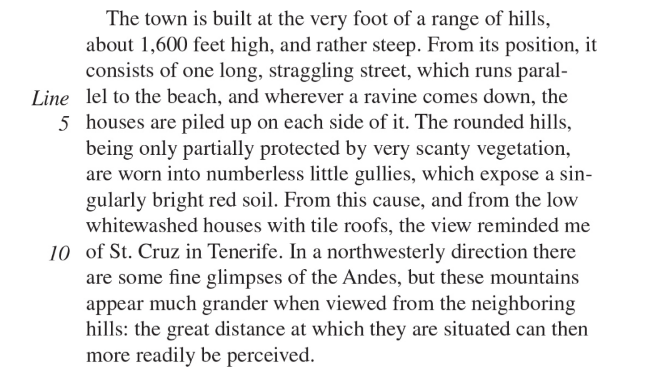

As an example of this, take a look at Charles Darwin’s depiction of Valparaíso, the chief seaport in Chile, in Voyage of the Beagle.

How and When to Use Description

- When possible, call on all five senses: visual, auditory, olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste), and tactile.

- Place the most striking examples at the beginnings and ends of your paragraphs (or essay) for maximum effect.

- Show, don’t tell, using anecdotes and examples.

- Use concrete nouns and adjectives; nouns, not adjectives, should dominate.

- Concentrate on details that will convey the sense you’re trying to get across most effectively. (Remember the fish bladders!)

- Employ figures of speech, especially similes, metaphors, and personification, when appropriate.

- When describing people, try to focus on distinctive mannerisms; whenever possible, go beyond physical appearance.

- Direct discourse (using dialogue or quotations) can be revealing and useful.

- A brief illustrative anecdote is worth a thousand words.

- To the extent possible, use action verbs.

Narration

A narrative is a story in which pieces of information are arranged in chronological order.

Narration can be an effective expository technique.

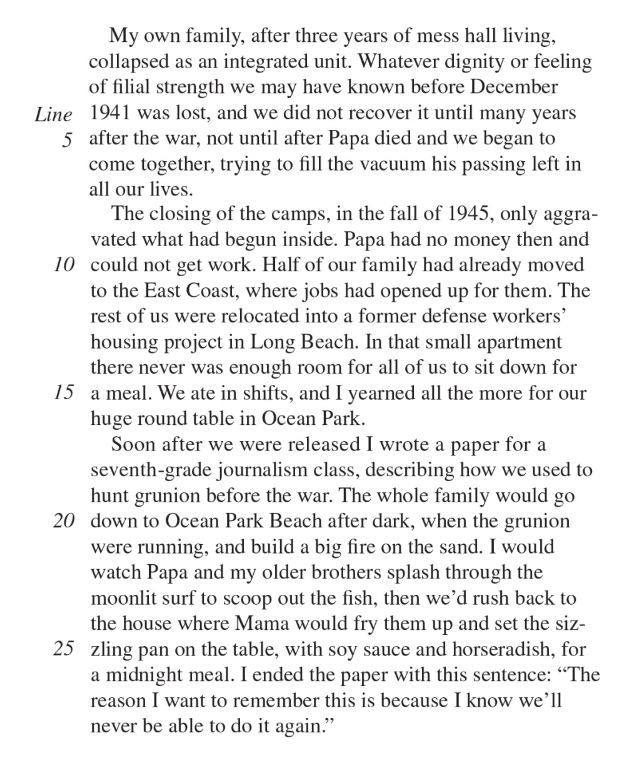

- Decades after her experience in a Japanese internment camp, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston decided to narrate her experiences before, during, and immediately after imprisonment.

- She did not want to tell the story just for the story’s sake; she wanted to relay her experience to the public to exorcise personal demons and to raise public awareness about this period in history.

- Here is a passage from this personal narrative.

- The passage describes the period after the Wakatsuki family had lost their house in Ocean Park, California, when they were forced into detention.

How and When to Use Narration

- When possible, structure the events in chronological order.

- Make your story complete: make sure you have a beginning, middle, and end.

- Provide a realistic setting (typically at the beginning).

- Whenever possible, use action verbs; for example, write “the fighters tumbled to the ground,” rather than “there were fallen soldiers on the ground.”

- Provide concrete and specific details.

- Show, don’t tell.

- Establish a clear point of view—if it’s clear who is narrating and why, then it will be easier to choose relevant details.

- Include appropriate amounts of direct discourse (dialogue or quotations).

Induction and Deduction

- Induction is a process in which specific examples are used to reach a general conclusion.

- Deduction involves the use of a generalization to draw a conclusion about a specific case.

How and When to Use Induction and Deduction

- Induction proceeds from the specific to a generalization.

- Make sure you have sufficient evidence to support your claim.

- Deduction is the process of applying a generalization to a specific case.

- Make sure your generalization has sufficient credibility before applying it to specific cases.

Next Chapter: Chapter 4: Rhetorical Fallacies