W10: Economic growth and the State

Growth and Crisis 1950-2023

Patterns of crisis:

WW1 and 2 connected as one crisis.

The rise of Macroeconomic theories: 1940s - 1970s Golden Age: Keynes and demand management.

By the 1970s Keynesian demand management was also incapable of addressing the newly emergent, more global economy which led to the rise of supply-side economics and monetarism from the 1980s.

1970s - 2009 Neo-liberalism, Globalisation and financialisaton

The challenge to Keynesianism by the 1970s revolved around a number of elements. Two of which were that exchange could only be developed in an environment whereby stability existed in prices. In an economy with rising and high inflation uncertainty existed, similar to that identified by Keynes forty years earlier, but now the state, government intervention and the multiplier effect, were no longer understood as the means by which stability could be achieved. Instead control over the supply of money and restricting its increase would be a means to control price inflation. The quantity theory of money became a bedrock on monetarist supply-side economics in the 1980s.

This was combined with a second element of monetarist economic thinking: the primary role of the market and market signals in determining investment. Government investment no longer was considered to generate multiplier effects for economic development. Now it was ‘crowing-out’ efficient use of resources. As the state grew bigger in its economic influence in the economy, government expenditure was said to be restricting the extent to which private investors could access capital for profitable investment.

Committing to the importance of the market meant a logic existed in relation to industrial policy. On the one hand industries which failed to be competitive would be left to fail, if they were unable to adjust to the new market environment, whilst those who were able to adjust to the new competitive market were able to thrive.

Associated with this logic was the development of policies which facilitated market signals to be amplified. Competition policy opened up new markets in the banking sector ‘big bang’ in 1986 removed restrictive legislation preventing new banks from opening up and existing banks from expanding into new forms of financial markets. The impact was the rapid growth of the City of London becoming one of the financial centres for global finance.

Neo liberal financialisaton and the rise of foreign exchange market, grew from $1.6t to $6.6t per day between 2001 and 2019. A global market for financial services emerged which dwarfed what had gone before.

These funds were mobile and sought the highest returns possible irrespective of their connectedness to the real economy. Arbitrage and speculation, day trading and shorting of stock could generate enormous profits for those with wealth enough to engage in these markets or those who traded other people’s wealth in these markets.

The second was to move state assets into the private sector through a process of privatisation. Within the UK, the ‘Tel Sid’ campaign in 1986 British Gas privatisation.

Within more traditional industries of the second and third revolution, cars, engineering, steel and shipbuilding the picture was less rosy with large-scale bankruptcy and manufacturing shrinking in its importance as a proportion of gross domestic product.

Just as Keynesian revolution was understood to be successful in its initial decades, so too was monetarism within economics and those who won out in the changes. The social costs of adjustment were understood as necessary consequences of these global changes.

But just as Keynesian revolution was undermined and challenged by the monetarist revolution so too was this challenged by the debates in the 2000s and especially sharply as the monetarist economic ideas failed to address the next crisis, ushered in with the Great Financial Crash of 2008-9.

Piketty Capital in the 21st century

“My object is to make people think” said Piketty. “I am a defender of the free market and private property, but there are limits to what markets can do.”

The emergence of patrimonial capital emerges from returns on savings being faster than the rate of growth of the economy itself leads to concentration of wealth in the hands of those who already hold wealth.

Keynesian under consumption and Modern Monetary Theory: money was now divorced from the economy, with low or zero interest rates meant money could be borrowed for free. Negative real interest rates existed. A variety of different forms of money now could exist from derivatives to crypto currencies.

Britain in November 2021 $65K to September 2023 $2.7K.

Tesla $601b share value in 2024 produced 1.4 million cars per year while Toyota valued at a fraction of Tesla, $283b produced 11 million cars per year in 2024.

The return of Marx and the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

2020 - Brexit, Covid and beyond

economics and globalisation

de-globalisation and Brexit

Agriculture, manufacturing and financial capital

imperialism and the end of empire

Ukraine, Russia and the US: the new war

covid - 2020 and the return of the state

Questions for the future

crisis today

low rate of profit encourages investment into fictitious capital

climate change and the future

The British Economy 1970-2023:

Intro

The post 1945 period of the British economy is without question the most important, politically charged and contentious of any period.

The post-war settlement ushered in a new era of government intervention within the economy and with it new areas of economic activity became the centre for social discussion and wider social opinion.

The post 1945 period has also been the era in which the British economy performed more spectacularly than in any other historical period, yet at the same time it continued to slip back against other advanced or newly advancing economies with the result that the ‘Golden age’ from 1951-73 is either exactly that or the golden failure and lost opportunity.

The first issue to point out is that as you should be well aware by now - do not expect writers to agree on issues. This is not simply a difference on the balance of interpretation but a wholesale difference of approach.

Different schools take fundamentally different conclusions from the evidence. Even within the same broad school of thought there will be widely divergent views.

Periodisation and Facts

Note:

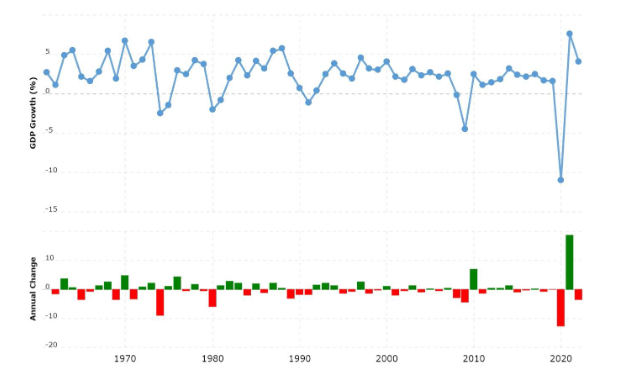

chart below highlights the rapid growth characteristic of the 1961-71 era, the ‘golden age’. By whichever method used growth rates were considerably higher than in later periods. Also productivity growth (measured as total factor productivity (TFP) was much higher.

total factor productivity is a measure of how economies use resources in new ways - hence a high TFP suggests that the economy was open to technological change and new production techniques in a way that was new and has not been repeated since.

crisis at the end of the long boom. Annualised GDP growth between 1973-9 - the next business cycle was less than half that of the long boom. TFP growth was almost negligible

the 1980s saw growth rates rise from the low of the 1970s - the suggestion was made that there had been an economic miracle and decline had been reversed. Nevertheless growth rates were never to return to the heights of the long boom.

Growth in the long boom was so strong that not even in the downswings of the business cycle did GDP contract. Recessions were growth recessions rather than absolute falls in output levels. Not without foundation then is the long boom considered to the ‘golden age’. Particularly compared with the period that has followed.

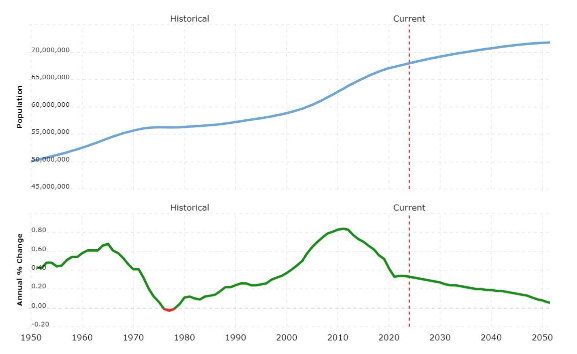

Acceleration in national growth rates after 1950 were universal through the golden period for all advanced economies. Nevertheless, against international comparisons the golden age of growth for the British economy looks less impressive. Britain started in 1950 as second wealthiest European economy in the industrial world measured by GDP/per capita (fifth behind USA, Switzerland, Canada and Australia in the world), however by 1973 it had fallen back to 7th by 1973 and 9th by 1992.

Essential points for any discussion

Decline for the British economy needs to be considered as relative decline not absolute. The economy has continued to grow, overall, throughout the period. By 1992 measured at constant US 1990 International dollars the GDP has expanded by 230% since 1945.

the second essential point for any discussion is that the relative decline may have very little to do at all with failure of the economy but instead simply be a result of Britain’s early start in industrialisation, catch up growth, or due to other natural endowments, historical legacy etc., which the British economy cannot ignore.

There is an inverse correlation between initial GDP per capita in 1950 and growth rates to 1990. Those with low national income had a greater distance to travel

Slowing down of growth rates after 1973 were also universal. Hence the reality of relative decline cannot be simply nor directly linked to failure. Challenging the assumption that decline is a result of failure is a central theme of those critical of the declinist message.

The supply-side explanations

Attempt here is a broad outline of key, repeating themes within the supply-side explanation.

1945-51 The years of recovery

The post-war settlement derived from examination of the market failures of the 1930s. Market mechanisms in the interwar economy had been seen to have failed. International free trade had been abandoned by the early 1930s. International currency trading and payments at fixed exchange rates had collapsed. Domestically the private economy had failed to grasp the rationalisation movement in the staple industries and a recognition that wages could not be readily reduced without increasing social conflict led to the ‘stickiness’ in labour markets to clear. The partial recovery of the mid 1930s wavered by 1937 and only government intervention in the form of rearmament brought renewed prosperity.

Full employment, improved diets due to rationing, new opportunities for women workers, childcare and healthcare systems of wartime produced proof that Keynesian demand management was superior.

By 1945 there was only a small fringe movement of economists such as Hayek who were opposed to the continuation of the state to actively play a role in the economy. Hayek’s book ‘Capitalism and the historians’ whilst a best-seller, indicating that an ideological resistance to the growth of the state existed, it remains the case that free marketer’s were still the ideological fringe.

A series of reforms brought in by the labour government from 1945-51 were designed and initiated by liberals and Tories. Beveridge, a liberal, produced the reports, which laid the basis for the NHS and Social Security system.

The 1944 Education Act, providing full time education for all under 15 years of age was implemented by the Labour government but introduced by the Tory Minister for Education Butler under the Churchill government.

Nationalisation of industry was with few exceptions, steel being one of them, was carried out with the approval and support of MPs from across the House of Commons.

However, within business Hayek’s ideas of a minimalist state were still strong. The employer’s organisations, the Federation of British industry was intensely hostile to the labour government and openly defined them over issues related to the restructuring of industry. British business/government relations in the early post-war years were therefore highly politicised.

Mancur Olson, The Rise and Fall of Nations

Economies over time develop what he describes as ‘distributional coalitions’. These coalitions, pressure groups may be employers associations, trade unions or pressure groups as innocuous as the Campaign for Real Ale. National Childbirth trust ect. Coalitions intervene in market processes extracting rents, which are then distributed within these coalitions. Economies which are stable for the longest periods will develop more of these and in doing so develop barriers to the free operation of the market.

Olson maintained that where these distributional coalitions are all-encompassing, involving the whole population they can promote growth by directing resources but where whey are not all-encompassing they will hinder growth. Olson further maintained that where nations suffer defeat in war, military occupation or social revolution these distributional coalitions are broken down which in turn frees market mechanisms and subsequent growth.

Reconstruction after the war is one area of intense debate on the origins of British economic failure.

Did reconstruction offer the opportunity to radically alter expectations, bargaining conditions and institutional arrangements? Should government fail to dispell these distributional coalitions? Should it have fundamentally challenged and altered the employers/government trade union bargaining environment?

If so, how? Competition policy has been suggested to have been weak and ineffectual in Britain after the war. Product markets were characterised by a lack of price competition, international competition has been suggested to have suffered from private cartel arrangements and government supported protectionism. International trade was restricted by both import controls and exchange controls. Did both of these reduce the opportunities for British firms to either compete or learn from abroad?

A further supply side issue relates to the growth of what is described as ‘increases in human capital’. Britain historically had a low level of university trained managers. British firms are said to have been dominated by the continuation of family control and/or a cult of the amateur. The manager who rose from the ranks, the gentleman whose concerns lay outside the firm are all suggested to have held back British firms when a professionalised, managerial class was required to develop larger and more complex business organisations. So did the education system fail to create a large enough layer of managers in Britain?

One important question then is did government squander the opportunity to reconstruct British business in a competitive fashion in the aftermath of 1945?

The Golden Age 1951-73

By the 1950s the use of Keynesian demand management was well established. Within a renewed international payments system, the European Payments Union, a renewed exchange rate system Bretton Woods and within an international economic support system, the IMF -Keynesian demand management appears to have been extremely successful. Indeed the Golden Age is increasingly seen as the exception rather than the norm in explanations of twentieth century growth.

If we have a more detailed look at the contributions to the rapid economic growth we see further evidence provided for supply-side explanations. The starting point for many is the accounting for growth. Growth accounting highlights the importance of productivity change in the golden age.

Population growth and the quality of labour

notes:

labour input - urbanisation in Britain being earlier than other economies

labour supply is a major constraint on the productivity of workers

capital input as a central feature of growth

as mentioned before TFP plays the major role (in an international context and a major role in the UK context) in the explanation of growth in the golden age

rapid TFP growth derives from a number of different areas. The role of Backwardness (catch up) as an element of TFP in boosting growth for economies such as France and Germany in relation to Britain. The transfer of technology, production techniques as well as post-war reconstruction and structural change, competition policy

lack of input from labour suggested to result from restrictive practices and trade union power.

residual efficiency - TFP is the error term from regression analysis. Residual efficiency is the error term once specific factors are factored out. Nevertheless, growth accounting also highlights a failure in residual efficiency within the British economy.

Here again supply-side explanations point to:

Long term stability allowing distributional coalitions extracting economic rent? was the government therefore captured by rent-seeking interest groups which resulted in a featherbedding of industry and a failure of firms to exit markets where they were unprofitable?

Perhaps government itself was the part of the problem?

Bacon and Eltis, Britain’s Economic Problem: Too Few Producers:

Suggested that government restricted the availability and cost of investment capital by the growth of state taxation and expenditure in the post-war period. Private investment was crowded-out at the expense of create transfer payments in the form of the welfare state and the existence of a large nationalised industrial sector.

Importantly government spending in the arms industry has been suggested to have dominated the R+D focus of British industry. R+D investment, qualified scientists and engineers were all absorbed into the arms industry at the expense of other sectors.

Could this investment have been used more productively? Or alternatively, again, was there too little government expenditure on R+D?

Elsewhere new growth theories examine the role of human capital accumulation, perhaps the British move towards wider university education in the 1960s was too late. The failure to develop a managerial class may have impacted on British competitiveness. The growth of mass higher education also coincided with a collapse of the apprenticeship system in Britain. British economic failure in human capital may be both a failure to develop a professional managerial class at one end of the spectrum and also a failure to develop vocational training among workers at the other end.

L Hannah, The Rise of the Corporate Economy

Within business itself mergers and the creation of large firms increasingly became important from the 1960s onwards. Government support for competition policy and industrial policy emerged from the 1950s and the British economy became highly concentrated. Large scale business organisation was expected to be able to invest on a level capable of creating competitive world class corporations. Did these mergers actually help or hinder the creation of economies of scale and scope. As we shall see much of the merger activity took place in response to competition legislation as firms merged to continue in their collusive practices but this time under a single corporate identity.

1970s and 1980s Crisis Decades

The 1970s and 80s were the two decades when the chickens came home to roost. A world slow down saw a collapse of growth rates.

What in the endogenous growth theory accounted for the growth that took place?

capital input again central

TFP no longer as impressive. Backwardness overcome but continuing residual efficiency

human capital shows negative sign as labour becomes surplus

By the mid 1970s a series of high profile private companies had collapsed, including Rolls-Royce, Ferranti electronics, British Leyland car manufacturer. While governments bailed these and other companies out by taking on their debts and providing operating capital a sea change in opinion was taking place. The free market ideas of Hayek were readily absorbed by Margaret Thatcher and the Tory party.

Within the 1974-79 Labour government these supply-side ideas also found a resonance. In 1976 the Prime Minister Callaghan announced an end and adherence to Keynesian demand side management. The changes that followed, including closing more hospitals than Thatcher ever managed, ensured a reaction and in 1979 Thatcher was first elected as Prime minister.

To what degree did the change of economic ideas alter the development of the British economy?

In general much was presented as significant changes in hindsight these changes are increasingly seen as far less significant.

1970s and 1980s characterised by return of mass unemployment and in the 1980s re-drawing of industrial relations legislation.

Inflation remained relatively high, government expenditure continued at a high level and growth failed to reach anything like the level of the long boom.

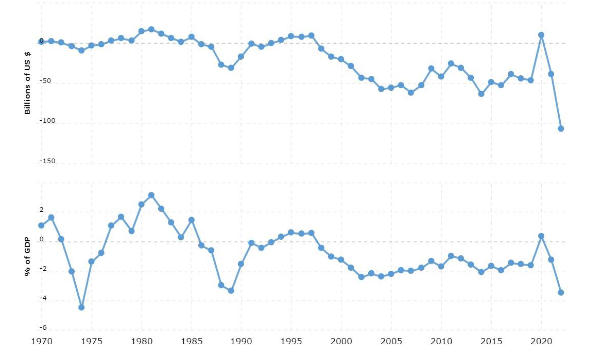

Trade imbalances and balance of payments deficits

Note:

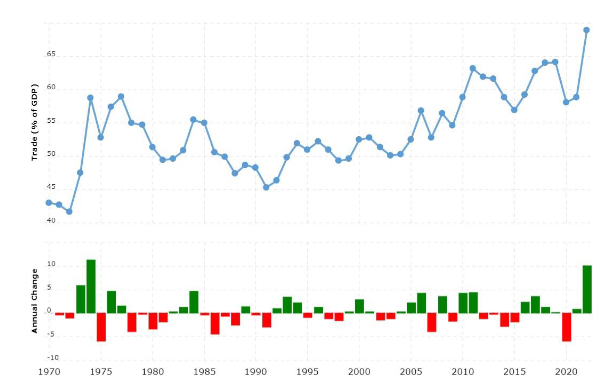

trade deficit as manufacturing declines and imports rise from the 1980s onwards. The value of sterling and the ability to exchange sterling for other currencies impacts on prices within the UK of consumer goods.

Internationally traded services from the financial sector played an increasingly important role in the finances of the UK economy.

Note:

the increasing openness of the economy from the 1990s

Brexit was attractive for those sectors seeking new international markets for exports, the internationally traded financial sectors in the City of London

Contemporary debates in Economics: State vs. Market

The Defeat of Truss Economics: Limits to the ‘free’ market

The shortest term of office for a Prime Minister saw Liz Truss exit Downing Street in just 48 days. This after the turmoil caused by crashing the UK economy in a way which has alienated large sections of the international capitalism, exposing major fault lines in economic thinking. The newly appointed Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng was himself sacked, making him the fifth Chancellor in 12 months and similarly gaining the accolade of being the shortest serving Chancellor in history, with the exception of a Chancellor who actually died after taking office. Kwarteng was of course sacked by the Prime Minister for carrying out her own policies with the result that Truss’s own premiership ended just 11 days afterwards.

The focus is the conflict Truss created within neo-liberalism and highlights the fracture that has always existed between the rhetoric of free-market economics and the reality of capitalist accumulation.

Truss’s economics represented a logic dominated by the concept of a free market, in which price signals determine the success or failure of capitalist firms. Other forms of co-ordination within markets such as regulation, government provision of goods and services or laws (excluding property rights) were understood as impediments to these market signals.

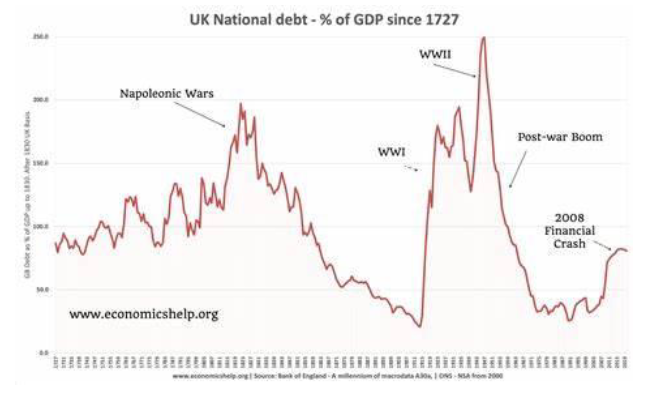

In contrast, however, market structures are ones in which governments’ not only act to frame competition by defining property rights but manage competition to favour their own capitals, ultimately acting as a backstop when crises inevitably occur within markets. Whether it was the Great Financial Crash in 2008 and the bailing out of the financial sector through the large-scale increase in public sector debt or the Covid pandemic requiring governments’ to fund private capital, along with its wage bill through furlough schemes, the state is inextricably embedded within the framework for market developments.

Unfunded tax cuts, rising debt and inflation were a trigger for a backlash within financial markets due to their undermining of the potential for the state to act as a backstop by Truss and Kwarteng’s mini budget. As business interests articulated their complaints against Truss and Kwarteng’s proposals were that ‘business needs stability’.

An explanation is needed, from the liberal and neo-liberal perspective, as to why changes in capitalist development and its weaknesses in relation to British capitalism proved so disastrous for the Tory government led by Liz Truss.

Capitalist markets are driven by the need to accumulate wealth and competition acts to drive out weaker firms, concentrating wealth in the hands of even larger firms. To remain the dominant firm in a market requires further investment in both technological ability and scale of production. In this sense capitalist markets are dynamic. In doing so this investment, combined with competition from rival firms, inevitably leads to a reduction in profitability of all firms in an industry. In this sense markets have crisis embedded within them.

Marxists explain this contradiction by recognising that these pressures inevitably lead to a tendency for the rate of profit to fall. In contrast, neo-liberal thought has attempted to resolve the question of why economic crises develop by focusing less upon their origins (the inability to continue to accumulate profit) and more on how crises can be managed. In doing so Truss and Kwarteng exposed a contradiction between those free-market perspectives that maintain you can simply let markets operate unhindered against those who recognise the necessity for the state to construct a favourable framework for managing crises and facilitate the accumulation of future profits.

Truss articulated her economic thoughts challenging what she identified as the ‘Treasury view’ and the orthodox economic neo-liberal view for ‘sound money’ in favour of a growth agenda which could be fostered via tax cuts both for rich individuals, by abolishing the highest income tax rate, and for business by reductions in corporation tax. When combined with additional restrictions on the rights of labour to strike, the entrepreneurial spirit of market capitalism could be unleashed from an anti-growth coalition which Truss and Kwarteng maintained has been missing from British capitalist development throughout the twentieth century. Truss and Kwarteng thus focus upon impediments to market signals operating as the cause of crises not the rate of profit itself.

The Treasury View

The criticism of British capitalism’s productivity failure, to grow at rates achieved by its competitors, articulated in the concept of the ‘Treasury view’ originates from the 1920s when, following the collapse of the international trade during WW1, the British Government returned to the Gold Standard. The Gold Standard was a fixed arrangement for currency valuation which ensured international trade could be paid for at pre-determined stable exchange rates. The return to gold in 1925 precipitated the 1926 General Strike and the mass unemployment of the 1930s as British exports found themselves uncompetitive in relation to international competition and employers pushed through pay cuts with swinging cuts to living standards in what was known as the ‘hungry thirties’. The British government were again forced to abandon the Gold Standard in 1931 and its collapse as a mechanism for regulating international trade was identified as one of the economic drivers for the outbreak of the second world war. Post WW2 attempts to revive stable exchange rates, with the Bretton Woods agreement, now using the dollar as the global currency then continued until its collapse in 1971, when the floating exchange rate system known today emerged. The interwar decades thus saw a transition from a more liberal market economy to a more state managed ‘state capitalist’ economy dominated by Keynesian ideas of demand management from the 1940s until this model’s collapse in the crisis of the 1970s.

A lack of investment and rationalism in private industry in the 1920s was identified as the cause of the relative economic decline facing British manufacturing. Government action to bridge this investment shortfall, identified as the ‘MacMillan gap’ failed to materialise due to hostility from the Treasury to sanction such intervention in private markets. City interests were suggested to have been given precedence over manufacturing as British financial institutions grew in global importance in what was defined as the ‘Treasury view’.

These criticisms of the City of London and a divide between financial and manufacturing capitalism have been a mainstay of a critique of British capitalism throughout the twentieth century, from both the political left and right. A critique to the Treasury view is associated with Keynesian approaches in which a dynamic state can substitute for the failures of private capital. However, a market-focused critique of the Treasury view is also associated with the political right, of which Truss articulated and can be found in the critique of government expenditure. Government action is responsible for ‘crowding out’ opportunities for more efficient private investment in Bacon and Eltis’s 1976 publication Britain’s Economic Problems: Too Few Producers. Reinvigorating market signals will, it is suggested, energise producers in manufacturing over those of financial institutions leading to a shift away from financial interests in the economy.

Ever since the 1920s economic historians have debated the origins of British relative economic decline and the mechanisms through which this failure has continued. Differing interpretations have placed the blame for relative economic decline on a failure of entrepreneurial spirit ‘gentlemanly capitalism’. British manufacturing’s support for cartelisation and monopoly over modernisation, failures of investment for newer technologies, to name a few. An example of the rightwing critique can be found in Corelli Barnet’s Audit of War which ‘the dank reality of a segregated, subliterate, unskilled, unhealthy, and institutionalised proletariat hanging on the nipple of state materialism’ prevented anything other than relative economic decline occurring.

Sound Money

The ‘Treasury view’ is itself rooted in the concept of sound money, the ability to manage exchange rates and facilitate international trade in goods and services. This concept was championed by Margaret Thatcher and monetarist economists in the 1980s as a means to weaken labour and restrict inflation. Here the argument was made that if the quantity of money circulating in the economy could be controlled prices would have to adjust to the limits of this supply. Money would be ‘sound’ as investors could have certainty that the future profits from investment would not be undermined by inflation and increases in the money supply.

The history of inflation under Thatcher’s government was, however, that inflation exceeded that expected from her monetary policies. Monetary targets set for the Bank of England were continually adjusted to address the inability to control the targets used for measuring the money supply. One reason for this failure was that the ideology of controlling the money to use to facilitate exchange and circumvent monetary policy. By the 1970s the Eurodollar market had already emerged and under Thatcher’s governments new forms of debt developed in the areas of consumer expenditure, with the expansion of credit card use, while in the area of corporate capitalism de-regulation of the financial sector saw newer forms of credit, derivatives as contracts for future trade, leveraged buy-outs and other forms of money expanded. This process has continued into the twenty first century, most notably with still newer alternative forms of money with the advent of crypto currencies.

Importantly, this rise in financial capitalism while portrayed as parasitical on ‘real’ manufacturing capitalism was symbiotic with manufacturing capitalism. Private manufacturing capital moved profits into wider financial markets in order to avoid reinvestment in new technologies for fear of undermining their own basis for profitability. Thus, the fossil fuel industry has the capital and dependency that has created the wealth in the industry itself. Oil firms risk undermining the very basis of their profitability, based upon an old pre-existing technology, and as a result move their profits into financial services. Oil companies can then gain greater profits from their financial services than actually producing oil.

A deeper explanation for the Monetarist failure lies in the fact that money is not simply a mechanism to facilitate exchange but also a mechanism for holding wealth. Money can be used as payment for trade but also to amass wealth. In its role as a mechanism for amassing wealth money has a different function. Here is can be used to speculate on short-term changes in the economy, through what is referred to as arbitrage. Rather than invest in productive assets, with the risk that the future profits from this investment will fail to accrue to the investor, speculation on future price changes can provide higher returns to investors. Additionally, where these price changes can be determined in advance by large scale financial institutions these profits can be substantial and as a result asymmetric information permits large firms to maximise profits in these markets. Thus, the market for foreign currencies as an example, the foreign exchange market grew from $1.6t to $6.6t per day between 2001 and 2019.

Anti-growth Coalition

The growth in the returns on financial assets exceeding those of output from firms since the crisis of the 1970s is the centrepiece of the critique of financial capitalism, developed by Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twentieth Century. While Piketty is not a marxist his work nevertheless documented the growing concentration of wealth in the 1% compared to the global 99%. Piketty’s evidence challenges one of the mainstays of mainstream economics, that equilibrium in competitive markets ensures the equalisation of real incomes for whole populations over time. The reality of the global growth since the 1970s, as Piketty charted, has been the opposite with rising income inequality and divergence rather than convergence of incomes within populations.

An explanation for the evident failures of trickle-down economies has been the focus of the second target of Truss and Kwarteng’s argument, namely an anti-growth coalition. This perspective lends itself heavily upon the work of the Chicago economist Deirdre McCloskey and the earlier work of the American political scientist Mancur Olson.

McCloskey’s critique of the work of Piketty and others who identify the stark levels of inequality in contemporary capitalism is to dismiss these concerns in favour of what she describes as ‘the Great Enrichment’ over the past two hundred years. Her perspective is that where markets operate free from restriction inequality will reduce overtime as returns to investment, in physical and human capital, equalise. Growth then rather than the distribution of wealth is the fundamental driver of capitalist development. McCloskey maintains that it is the size of the cake not its distribution that is of utmost importance while, of course ignoring the transition costs for those baring the cost of this adjustment, namely through poverty, war and destitution. More recently we could add the environmental costs to the environment of traditional, carbon based forms of industrialisation. For McCloskey what is required is more time for Piketty’s evidence to demonstrate this inevitable equalisation. Does the planet and with it the existence of human kind have sufficient time to wait for this adjustment?

In answer to the question: why does the historical evidence demonstrate low levels of growth coincide with a lack of such redistribution within contemporary capitalism? It is suggested to arise due to what Olson identifies as ‘distributional coalitions’ and their sclerotic tendencies to reduce growth within economies. Distributional coalitions, where they bring about changes for sub-groups in the population, whether related to childcare, any form of social or trade networks, trade unions or employer bodies all act to redistribute surpluses. According to Olson economies suffer from institutional sclerosis resulting from these distributional coalitions redirecting surpluses away from productive investment leading to a redistribution away from growth enhancing areas. An inevitable historical tendency towards sclerotic tendencies arising from the development of distributional coalitions in stable societies, thus hindering economic development. Olson then provides solutions to these tendencies in the crisis ridden process of defeat in war, civil war or military occupation whereby distributed coalitions are broken apart and free markets re-emerge.

Shock Therapy

In the primacy awarded the free market, the focus upon growth to the exclusion of redistribution, the disruption of the Treasury view and the attacks on the anti-growth coalition the Truss Kwarteng mini budget attempted to apply shock therapy to the British economy. The shock treatment used in Chile after the overthrow of the Allende Popular Unity government in 1973 and the shock therapy applied to Russia after 1989 was now to be introduced into the British economy in order to wipe out sclerotic inducing distributional coalitions, instil an entrepreneurial spirit and let market signals operate unhindered.

British and international capitalist firms and institutions rejected these proposals for a shock treatment decisively. Asset holders and financial markets rapidly abandoned British government debt, pushing up interest rates, and devaluing Sterling, reducing the value of the pound against other currencies.

Truss maintained this was due to the poor signalling of their intentions, ‘they went too fast’. British capitalism wasn’t prepared to follow the route of the Russian economy after 1989, not because they oppose growth but rather the construction of the post Brexit free(er) market for British capitalism currently guarantees the redistribution of surplus value into the hands of capitalist firms operating within the British economy. Brexit, in removing regulation from financial markets and allowing the financial sector to act as an off-shore tax haven for Europe and the development of tax-free Enterprise Zones and Free Ports for the manufacturing and distribution sectors respectively were creating de-regulated freer markets for large-scale capitalist firms. This architecture was being constructed without removing the government safety net in the form of the ability for the British government to borrow. Truss and Kwarteng, believed accelerating this agenda would promote new growth opportunities, but it was one in which uncertainty over which firms will survive in this freer market led international capital to abandon the Truss government and move swiftly to prevent its implementation.

The short lived Truss experiment in free market economics placed neo-liberal ideology over and above the reality of capital accumulation. While maintaining an ideology of free markets British capitalism is completely dependent upon the integration of the state with private firms, in constructing a framework for accumulation which guarantees profitable outcomes for British capitalism. Post-Brexit this newly emerging architecture for British capitalism of de-regulation and low taxes for business was already facing threats to its fulfilment, as the dethroning of Prime Minister Boris Johnson MP had already testified. The failure to deliver on the advantages of Brexit, combined with the emergent social conflicts and industrial unrest together, led to the collapse of support for Boris Johnson as Prime Minister.

With the appointment of Rishi Sunak as Prime Minister the moves to reduce the public sector and weaken labour’s influence via trade unions will continue, but the role of the state as a stabilising institution within capitalist markets can still be assured. A step towards freer markets proved a step too far for one of the weakest capitalist economies in the world and a return to the integration of state and private capital will be re-established. As a result, the problem of managing the tendency towards low growth rates with higher levels of state intervention in the British economy will also remain unsolved.

Mariana Mazzucato: what is the role of government in the modern economy?

Mazzucato’s approach recognises the importance of the state in developing market economies. Her work on the entrepreneurial state focuses upon the significance of the state in not simply defining the ‘rules of the game’ but encouraging the game to take place through state directed entrepreneurial activities.