Ch.14 L1-4 Summary

Lesson 1: Selecting Cases at the Supreme Court

The Function of the Supreme Court

What is the role of the Supreme Court in our democracy?

The Supreme Court is the highest court in the land and as such sits at the top of the judicial branch in our democracy. The Court’s primary function is to resolve disputes that arise over the meaning of federal law and the U.S. Constitution.

One of the Supreme Court’s most important powers is judicial review.

Can decide what a federal law means or whether any law is unconstitutional.

This power is not specifically mentioned in the Constitution.

Choosing Cases

How does the Court decide which cases to hear?

Jurisdiction

The justices can only decide issues that come to them through the court system in the form of legal cases. Those issues are limited to determining what a federal law means or deciding whether a law or government action is constitutional.

The Supreme Court has both original and appellate jurisdiction.

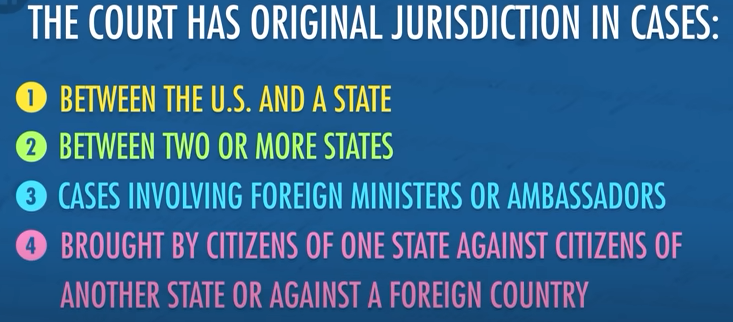

Article III, Section 2, of the Constitution sets the Court’s original jurisdiction. This article and section address two types of cases:

When Maryland and Virginia argued over oyster fishing rights, the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction.

Most of the cases the Court decides fall under the Court’s appellate jurisdiction—appellate comes from the word appeal.

Under its appellate jurisdiction, the Court hears cases appealed from lower courts of appeal, or it may hear cases from federal district courts where an act of Congress was held unconstitutional.

It must usually wait for a trial to be held and for the losing party at the trial to appeal the case to at least one higher court. Then the losing party from the appeal may be able to seek Supreme Court review. It cannot issue advisory opinions—a ruling on a law or action that has not yet been challenged in court.

Summarizing Under what conditions can the Supreme Court hear a case?

Conflicts and Importance

The Supreme Court is concerned about ensuring uniformity in decisions about the meaning of the Constitution and the interpretation of federal laws.

They also choose cases that raise major questions about the law that will have a national impact—questions that they believe must be answered for the good of the country.

This includes controversial issues like abortion, privacy, or the death penalty, as well as politically charged topics like campaign finance and business cases.

While not grabbing headlines like cases involving social issues, these cases can involve billions of dollars and directly affect many people’s lives.

In order to have their cases accepted, these people must usually show that their case raises a question about a federal law or the U.S. Constitution, and that the question has been answered differently by lower courts.

For example, in 1963 Clarence Gideon appealed his conviction from a Florida state prison. He argued that the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteed him a right to a lawyer at his trial—a right that he had been denied. The Court accepted his case and ruled in his favor.

Petitions for Certiorari

The party that appeals to the Supreme Court is generally the party who lost in a lower court—either in a federal circuit court of appeals or a state supreme court.

To appeal, the losing party sends the Court a petition for a writ of certiorari. In this document, the Supreme Court is asked to hear the case and given reasons it should do so. At this stage, the petition does not suggest how the Court should decide the case—just that it should decide the case.

For example, the petitioner might argue that two or more federal courts of appeal have ruled that the federal law means two different things, and that the Court must step in to assure national uniformity.

Solicitor General

The solicitor general is the government official most often responsible for representing the federal government in court.

The solicitor general decides which cases to appeal to the Supreme Court and how to respond when others appeal a case involving the federal government. Sometimes, when the justices are considering whether or not to accept a case, they will ask the solicitor general to submit the government’s views.

Selecting Cases to Hear

The law clerks look for cases that clearly present a federal legal issue that is important and that has divided the lower courts.

The law clerks from most of the justices’ chambers work together in a “cert pool” and divide up the task of reviewing the petitions and writing summaries. Some justices do not participate in the pool. These justices and their law clerks review all the petitions.

The justices meet to decide which cases they will hear. If four of the nine justices agree to hear a case, then the petition for certiorari is granted, and the case is scheduled for argument. This unwritten rule is called the rule of four.

Describing What are the different ways that a case can reach the Supreme Court? Which is least common? Why?

Lesson 2: Deciding Cases

Arguing and Deciding Cases

How are cases argued and decided by the Supreme Court?

Unlike a trial court, the Supreme Court does not hear witness testimony, accept evidence, or have a jury. The nine justices read written arguments from the parties and notes from their clerks, and participate in one hour of oral argument for each case.

Briefing

Once the Court decides to hear a case, each side submits a written brief, explaining how they want the Court to decide their case and the best arguments in support of that decision.

An important part of their legal brief involves pointing out similar cases the Court has already decided and noting how the decisions in those cases (precedents) support their argument.

The solicitor general can also submit a brief on behalf of the federal government to explain the United States’ perspective on the issues in the case.

Oral Argument

Each side has 30 minutes to present its case to the justices. The justices, who have already read the briefs and studied the case, ask many tough questions.

In cases where the federal government is a party, a lawyer from the solicitor general’s office will usually present the oral argument for the United States.

Or when it has an interest in the case, the solicitor general’s office might also present the federal government’s views about the party whose side the government supports.

Deciding the Case

One justice is assigned to draft each opinion, or ruling, in the case. The person who has been serving on the Court the longest decides who will write the Court’s opinion.

If there are dissenters, the most senior justice among them assigns someone to write a dissenting opinion.

Once the opinions are drafted, circulated, revised, and put in final form, they are announced in court. The Court’s written opinions are its way to communicate with Congress, the president, interest groups, and the public.

Enforcing Decisions

Describing What are written briefs and oral arguments and how are they used in deciding Supreme Court cases?

Influences on the Court

What influences the Supreme Court justices’ opinions on cases?

Public Opinion

Because the Supreme Court justices are not elected, the Court is fairly well insulated from public opinion and daily political pressures.

They know that when the Court moves too far ahead or lags too far behind public opinion, it risks losing support and diminishing its own authority.

When they issue decisions that may be unpopular with the public, they are aware that they rely on the cooperation and goodwill of others to enforce its decisions.

For example, in one ruling against voter discrimination in the South, the Court reassigned the opinion to Justice Stanley Reed, a Southerner, hoping that this would produce an opinion more broadly acceptable throughout the country.

Values of Society

The values and beliefs of society influence Supreme Court justices. As society changes, attitudes and practices that were acceptable in one era may become unacceptable in another. In time, the Court’s decisions will usually reflect changes in American society.

Some of the Court’s decisions on racial segregation provide an example of how the Court changes with the times. In 1896, in Plessy v. Ferguson, the Court ruled that it was legal for Louisiana to require “separate but equal” treatment in a public accommodation (a railway car).

Analyzing To what extent do you think the Court is affected by the public’s opinion and societal values? Explain.

Lesson 3: Selecting Supreme Court Justices

The Nomination and Confirmation Process

How are Supreme Court justices nominated and confirmed?

The justices are not elected, nor are they accountable to anyone—just to the law.

Lifetime appointments to the Court are designed to ensure a fair and impartial judiciary.

Similar process to federal judges.

Supreme Court justices may keep their jobs for life, unless they are impeached, which is very, very rare.

Constitutional Requirements

The Constitution does not say much about who should serve as a federal judge. There are only two requirements:

the person must be nominated by the president

and receive the consent of the Senate.

The president …

“… Shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint … Judges of the supreme Court …”

Confirmation by the Senate

The Process and Politics

The choice made by the president is a political decision: the president selects a nominee who is confirmable by the Senate.

Once the president has chosen a candidate, he or she will be introduced to the public, and the Senate Judiciary Committee will schedule a confirmation hearing.

At the hearing, senators are interested in the approach the nominee will take to deciding controversial issues once on the Court.

The committee votes on whether or not to send the nomination forward to the entire Senate.

If the nominee receives a majority of the committee votes, the entire Senate then votes.

Technically, a nominee needs a majority of the votes cast in the Senate to be confirmed, but in recent years, nominees have needed the support of 60 senators in order to avoid a filibuster.

Some observers believe that the most important factor in whether the nominee gets confirmed is the political popularity and strength of the president.

In 2016, republicans, worried that a conservative justice might be replaced with a liberal justice, refused to hold hearings on a nomination.

They argued that the people should weigh in on the process through the election of the next president.

President Obama rejected this logic and nominated judge Merrick Garland to the court. The Senate did not act on his nomination.

The Selection of Supreme Court Justices

What characteristics make someone an ideal nominee for the Supreme Court?

Merit and Ideology

Some presidents want justices with extensive experience as a judge, while others might want justices who have more experience prosecuting criminals or dealing with Americans’ everyday concerns.

Representativeness

Explaining What characteristics do presidents look for in a Supreme Court nominee?

Lesson 4: Constitutional Interpretation

Interpreting the Constitution

How do judges decide what the Constitution means?

Citizens, interest groups, businesses, and many others have different opinions about the role the Supreme Court should play in our federal system when it uses the power of judicial review.

Should judges seek to change society or leave making changes to our elected representatives in the legislative and executive branches?

Some advocate judicial restraint; others argue for judicial activism.

Judicial Restraint and Judicial Activism

Those who support judicial restraint believe that the Court should avoid overturning laws passed by democratically elected bodies, like Congress or state legislatures.

If the Court overturns such laws, it becomes too involved in socio-politicals

They believe the Court should uphold acts of Congress unless the acts clearly violate a specific constitutional provision.

In other words, the Court should leave policy making to elected officials.

Those who support judicial activism believe the opposite: that the Court must step in when Americans’ rights are violated.

This means the Court would actively help settle the difficult social and political questions of the day.

Under Earl Warren, chief justice from 1953 to 1969, for example, the Court overturned many laws limiting the civil rights of minorities.

Judicial activism can also serve conservative goals.

In the 1930s, for example, conservative justices often took activist positions against New Deal programs intended to regulate the economy.

Historically, liberals have been more likely to support judicial activism, and conservatives have been more likely to support judicial restraint. However, this generalization has not held true in recent years.

Influences on Decision Making

The justices must decide how to determine what the text of the Constitution means when the words are unclear.

When justices are reviewing cases, how can they decide what “cruel and unusual punishment” (from the Eighth Amendment) or “unreasonable search and seizure” (from the Fourth Amendment) means today?

Two major influences on the decisions justices make are precedents and judicial philosophy.

Precedent and Stare Decisis

One of the basic principles of law in making judicial decisions is stare decisis (“let the decision stand”). Under this principle, once the Court rules on a case, its decision serves as a precedent to base other decisions in cases that raise the same legal issue.

This principle is important because it makes the law predictable. If judges’ decisions were unpredictable from one case to another, what is legal one day could be illegal the next, and respect for the law would diminish.

Judicial Philosophy

Supreme Court justices explain their decisions in terms of law and precedents. However, it is the justices themselves who determine what laws mean and what precedents are important based upon their judicial philosophy.

This is their idea about what guidelines to use when interpreting the Constitution.

Critics of this approach say that we cannot always determine what the people understood the Constitution to mean at the time of its ratification.

Moreover, it is impractical to have the views of people from 200 years ago govern us today.

It is also difficult to figure out how their understandings of the document apply to new technologies such as the Internet or drone aircraft.

Supporters of this philosophy believe that the meaning of the Constitution must evolve because it is a living document. This flexibility has allowed it to be used as our basis of government for more than 200 years.

They think such an approach may also result in greater public support for decisions because interpretation of the Constitution can align with contemporary values and standards.

They point out that it is very difficult to amend the Constitution and that the document cannot be amended every time a new technology is invented or a new situation arises. The Constitution must be applicable to conditions that the people of the 1780s never imagined.

Critics of the living constitution say that it is an invitation for judges to make up the law. If the Constitution’s meaning changes over time, then it is not fixed and is not really law. It is dangerous and undemocratic for unelected judges to create meaning in the Constitution.

Checks and Balances on the Supreme Court

How is the Supreme Court’s power limited and balanced by the other branches of government?

The president has the power to appoint justices, while the Senate has the power to approve or reject those appointments.

Congress has the power to impeach and remove justices. Congress even decides how many justices will be on the Supreme Court and sets their salaries.

If the American people do not like a Supreme Court ruling, they can (through their elected representatives) change the law or the part of the Constitution that the Supreme Court interpreted.

For example, think about a federal law that bans discrimination against people with disabilities. If the Supreme Court decides that the law means that private clubs need to install wheelchair ramps—but Americans disagree with that decision—then Congress can amend the law to exclude private clubs.

If the people do not like a Supreme Court ruling about the Constitution, however, they must go through the more difficult process of amending the Constitution.

This has happened in the past. In an 1895 case, the Court ruled that a tax on incomes was unconstitutional. The Sixteenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, allowed Congress to levy an income tax.

Discussing What are ways that the legislative branch can check the power of the Supreme Court?