L4: Precipitation nucleation

Learning Objectives:

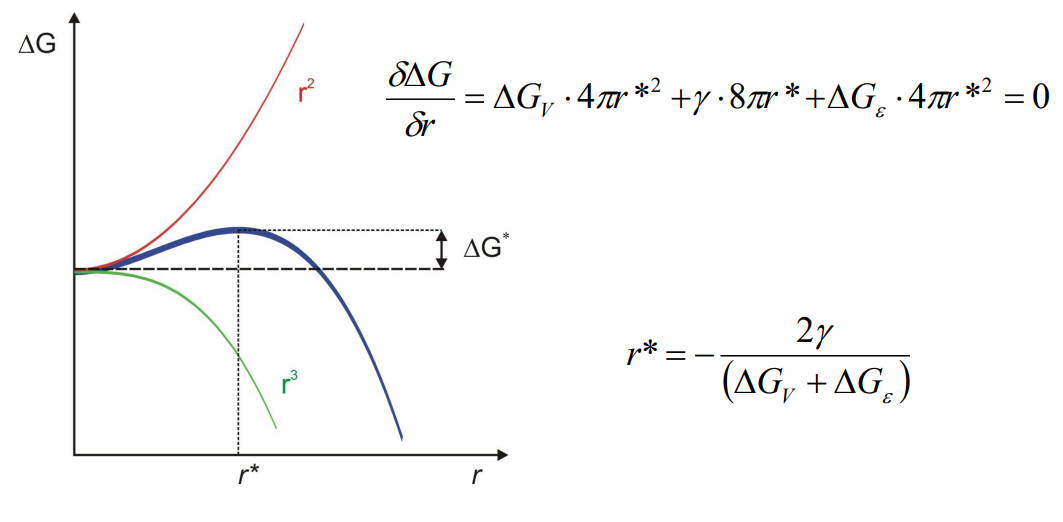

Derive the equation controlling the free energy changes upon nucleation

Phase change negative; strain and surface energies positive

Discuss the critical size of a nucleus and the energy barrier to be overcome.

Found by taking derivative of delta G and setting to zero. Depends on undercooling.

Develop a simple prediction for the nucleation rate and explain its variation with temperature

With increasing undercooling there is a trade-off between (i) high driving force, and (ii) slower diffusion.

Show that heterogeneous nucleation, e.g. on a grain boundary, is much easier than homogeneous nucleation

determined by relative energy of boundary (or defect) and precipitate. High undercooling = more homogenous nucleation

(1) Derive the equation controlling the free energy changes upon nucleation:

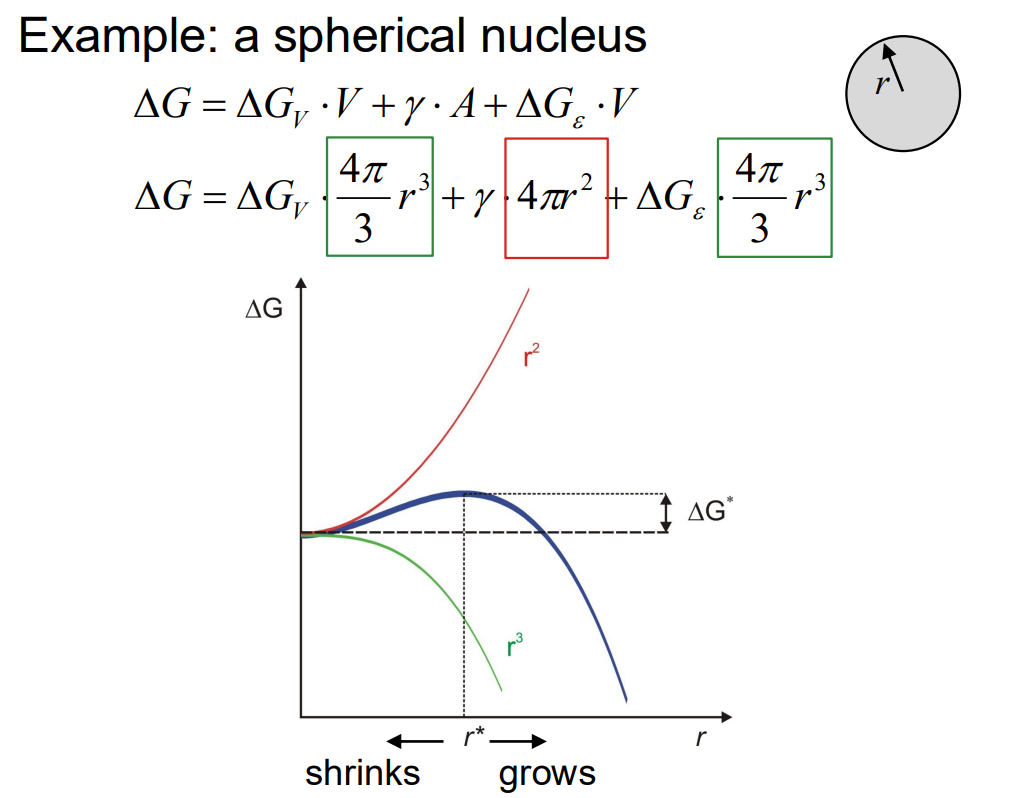

The free energy change (ΔG) upon nucleation is influenced by three main factors:

Volume free energy change (ΔGv): This is the driving force for nucleation, which is negative as it represents the energy reduction when a more stable phase forms.

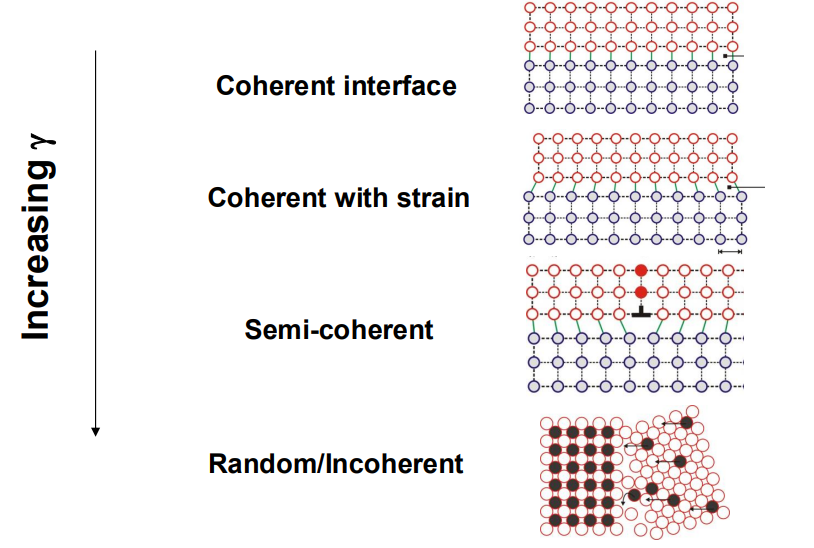

Surface energy (γ⋅A): This is the energy required to create the interface between the new phase and the matrix, which is positive.

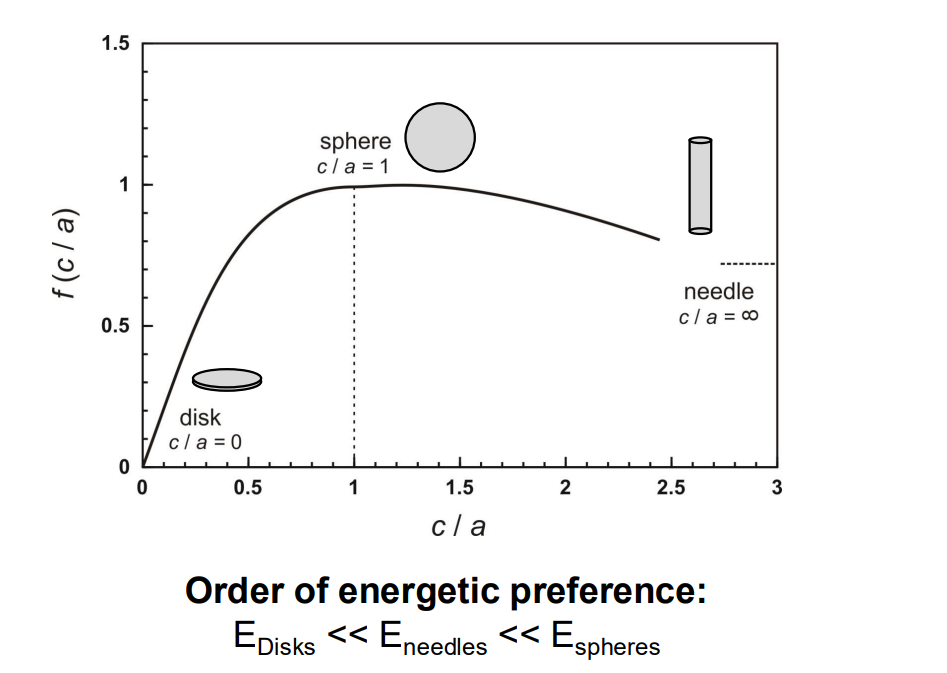

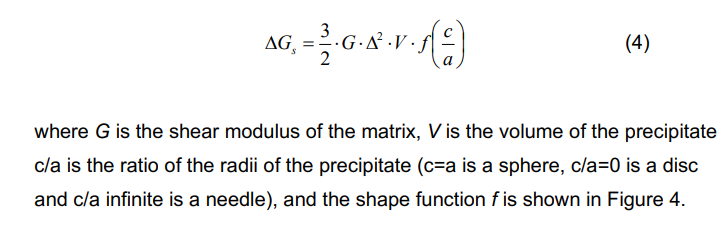

Misfit strain energy (ΔGe): This is the energy associated with the volume mismatch between the new phase and the matrix, also positive.

The overall free energy change for a spherical nucleus is given by:

where r is the radius of the nucleus.

(2) Discuss the critical size of a nucleus and the energy barrier to be overcome:

The critical nucleus size (r∗) is the size at which the nucleus can grow rather than shrink. It is determined by setting the derivative of ΔG with respect to r to zero:

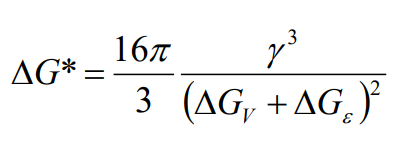

The energy barrier (ΔG∗) for nucleation is the free energy change at the critical radius:

This barrier must be overcome for nucleation to occur.

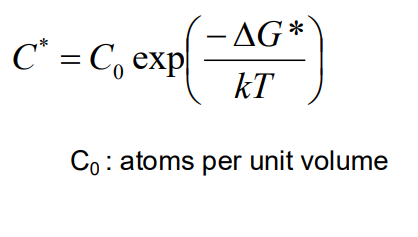

(3) Develop a simple prediction for the nucleation rate and explain its variation with temperature:

The nucleation rate (Nhom) depends on the concentration of critical nuclei and the rate at which atoms can diffuse to form these nuclei. The concentration of critical nuclei is given by:

where C0 is the number of atoms per unit volume, kk is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature. The nucleation rate is then:

where f0 is a pre-exponential factor and ΔGm is the activation energy for diffusion.

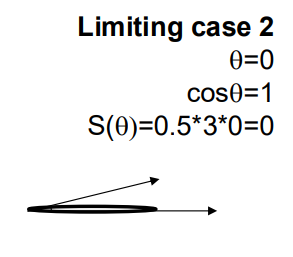

The nucleation rate initially increases with undercooling (lower temperature) due to a higher driving force (ΔGv), but at very low temperatures, diffusion slows down, reducing the nucleation rate. This results in a peak nucleation rate at an intermediate temperature.

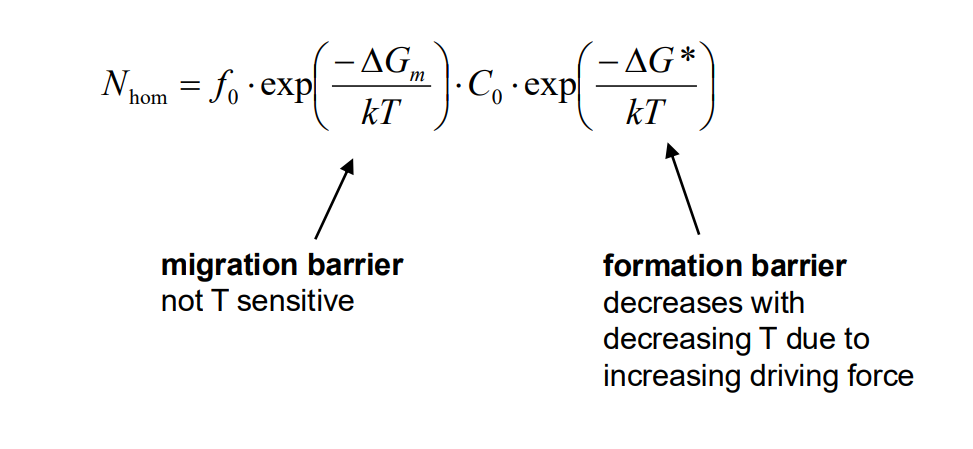

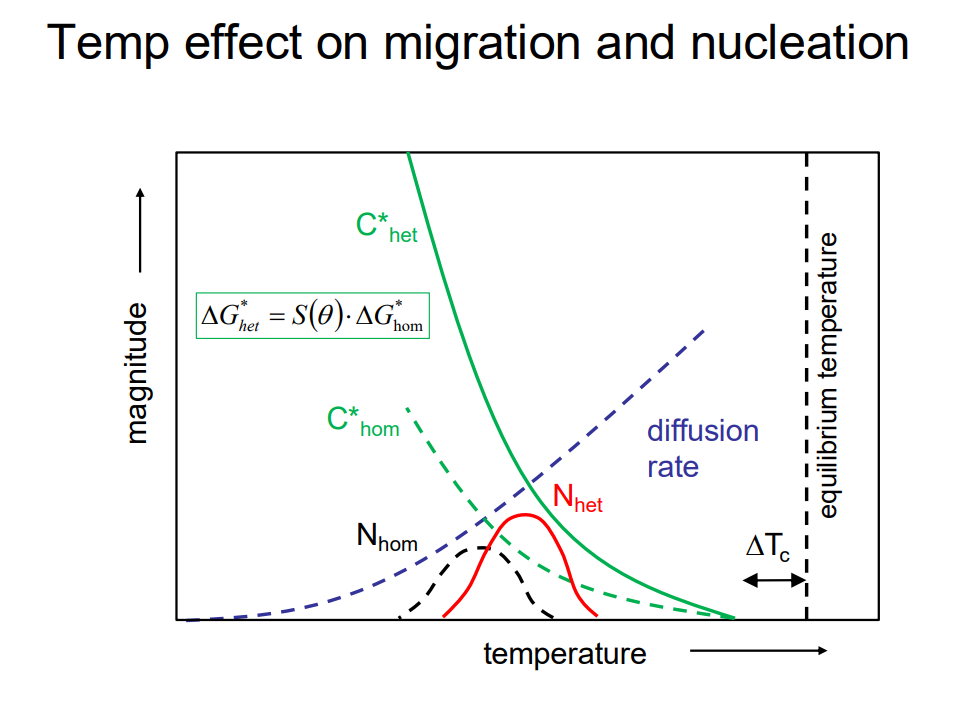

(4) Show that heterogeneous nucleation, e.g. on a grain boundary, is much easier than homogeneous nucleation:

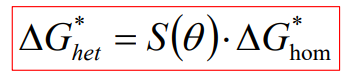

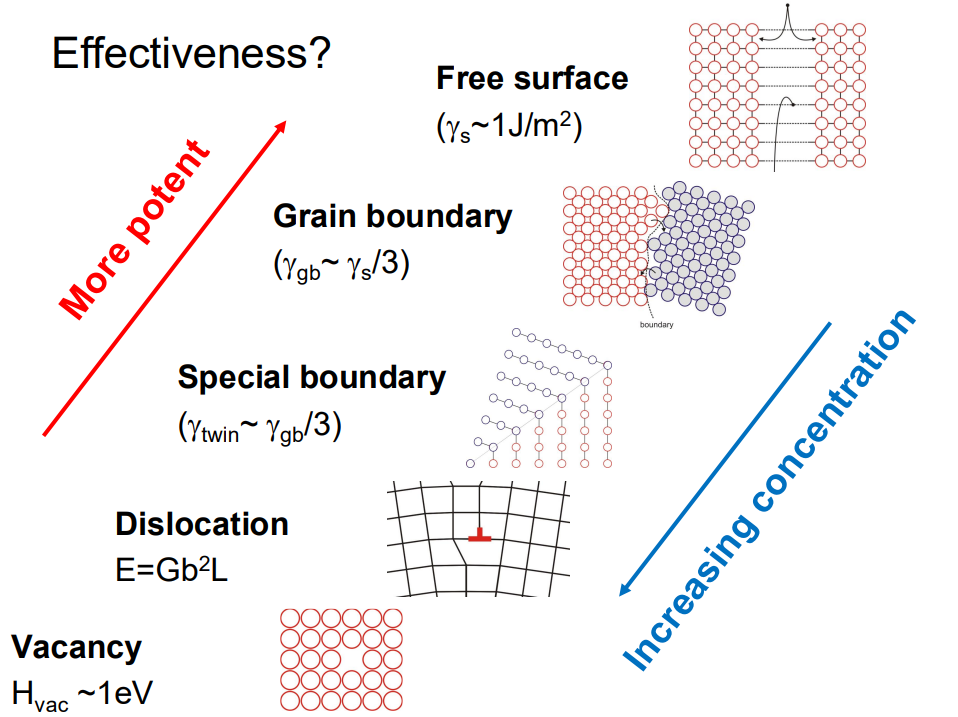

Heterogeneous nucleation occurs at defects like grain boundaries, dislocations, or impurities, which reduce the energy barrier for nucleation. The energy change for heterogeneous nucleation (ΔGhet) is modified by a shape factor S(θ):

θ is the contact angle between the nucleus and the grain boundary. Since S(θ)<1S(θ)<1, the energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation is lower than for homogeneous nucleation, making it easier.

Green curves (C∗): Critical nucleation concentration for heterogeneous (solid) and homogeneous (dashed) nucleation.

Red & Black curves (N): Nucleation rates; heterogeneous (Nhet) peaks earlier and higher than homogeneous (Nhom), meaning it's easier to nucleate on surfaces.

Blue dashed curve: Diffusion rate increases with temperature.

Key takeaway: At low temperatures, nucleation is favoured; at high temperatures, diffusion dominates. The balance between these controls phase transformations

In summary:

Heterogeneous nucleation is favoured because defects reduce the energy barrier.

The nucleation rate peaks at an intermediate temperature due to a trade-off between driving force and diffusion rate.

The critical nucleus size and energy barrier are determined by balancing the driving force, surface energy, and misfit strain energy.

Knowt

Knowt