The economic way of thinking - 3. Substitutes everywhere, the concept of demand

- Recap:

- Most goods are scarce: they can be obtained only by sacrificing some other good

- There are substitutes for anything

- Everyday choices entail trade-offs: comparing expected additional costs against expected additional benefits.

On the notion of needs

- What is the relationship between the claim that people face "trade-offs" versus the claim that people have genuine "needs"?

- Economic way of thinking doesn't deny that real people have real needs, but it does suggest that these statements can be misleading.

- As the sacrifice or cost increases, people tend to search for substitutes.

- Ex: an upcoming physics midterm raises the cost of reading the assigned chapter in economics. The student might read a summary instead of the whole chapter.

- Ex: the lower the price of visiting a doctor, the more frequently people substitute a trip to the doctor for other remedies.

Marginal values

- Our choices depend on the situations we face.

- Just about anything could be more valuable than anything else under appropriate circumstances.

- Like choices, values depend on the situation too.

- The values that matter are marginal values.

- Marginal: on or at the edge.

- ==A marginal benefit or cost is an additional benefit or cost==

- What do I expect to gain? What do I expect to sacrifice?

- Ex: water vs diamonds.

- When we make decisions, we don't do them in terms of "all or nothing", rather, more of this versus less of that.

The demand curve

Demand: a concept that relates amounts people want to obtain to the sacrifices they must make to obtain these amounts.

- Consume means a person tries to acquire and use a specific amount of a good for a variety of different purposes.

- Quantity demanded: the amount that consumers plan to purchase at a given price.

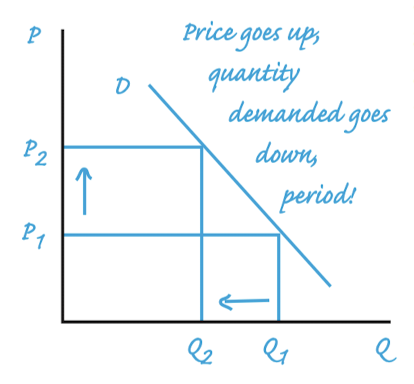

- Demand curve: illustrates the amount of a good that consumers plan to purchase at any given price.

- Quantity demanded and demand curve are not the same.

- Demand is a curve. We move along a demand curve.

- Quantity demanded is a specific amount that consumers plan to buy at a specific price.

When faced with higher prices, people tend to conserve a resource, to seek out substitutes.

- Consumers make marginal adjustments to changes in the price of a goods. They don't engage in all-or-nothing trade-offs.

- They seek out more economically efficient ways of accomplishing their goals.

- It takes time to find substitutes.

Law of demand: negative relationship between price and quantity demanded, other things being constant.

- If a price increases, the quantity demanded will decrease, and vice-versa.

Demand itself can change due to:

- A change in the number of consumers.

- A change in consumer tastes and preferences.

- A change in income.

- Normal good: income and demand move in the same direction.

- A change in the price of a substitute good.

- A rise in the price of a given good will tend to increase the demand for the substitute good.

- The price of a single good has meaning only when considered against the prices of the vast array of other goods.

- Everything depends on everything else

- A change in the price of a complementary good.

- Complementary goods are goods that are consumed and used together.

- A change in the expected price of a good.

- "Let's buy more now before the price goes even higher"

One major reason why people don't think the law of demand works is because they don't take inflation into consideration.

- Inflation: an increase in the average money price of goods.

- Inflation muddies the price signals.

- All money prices do not change in equal proportion as a result of inflation, but they do tend to move together.

What role should demand play? it's a property rights issue.

Price elasticity of demand

- Elasticity means responsiveness.

- How sensitive are buyers to a change in price?

- Price elasticity: the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price.

- When the coefficient of elasticity is greater than 1, the demand is elastic.

- It is influenced by three factors:

- Time: the longer the period people have to adjust to price changes, the more elastic demand will become.

- The availability and closeness of known substitutes: the more substitutes, the greater the elasticity of demand.

- The proportion of one's budget spent on a good: the smaller the proportion of one's budget spent on a good, the less sensitive consumers will be to price changes.

- Demand curves are not completely inelastic over the entire price range.

- Most purchasers will respond at least a little to changes in the cost to them, and all purchasers will respond to a sufficiently large change.

- A completely inelastic demand curve would graph as a vertical line, suggesting there are no substitutes for the good in question.

Money costs, other costs, and economic calculation

- The concept of demand doesn't suggest that money is the only thing that matters to people.

- As the opportunity cost of an action increases, the chooser will tend to undertake less of that action.

- People compare additional costs to additional benefits in whatever way that cost is conceived.

- Price measured in money allows for economic calculation.

Summary

- Trade-offs, trade-offs, trade-offs—most goods are scarce, which means that they can be obtained only by sacrificing other goods.

- There are substitutes for any good. Economizing is the process of making trade-offs among scarce goods by comparing the expected additional benefits and the expected additional costs from alternative ways of pursuing one’s objectives. Marginal benefits and costs are the additional benefits and costs expected in the existing situation.

- The concept of “needs” overlooks what the concept of demand emphasizes: the great variety of means for achieving ends, and the consequent importance of considering trade-offs.

- The “law of demand” asserts that people economize: They will want to purchase more of any good at lower prices and less at higher prices.

- The demand for a good expresses the relationship between the price that must be paid to obtain the good and the quantity of the good people will plan to purchase. Demand is a curve and should not be confused with the specific quantity that will be demanded at any particular price.

- Don’t confuse a change in quantity demanded with a change in overall demand! If the price of a specific good changes, holding everything else constant, only the quantity demanded for that good is subject to change. In the graph, we simply move along a given curve.

- When economists say that demand itself increases or decreases, they mean the entire curve shifts right or left, and there are six general reasons why this can happen. Other things constant, demand will increase if (1) the number of consumers increases, (2) consumer tastes and preferences change, making the good more desirable, (3) income increases if the good is a normal good, or income decreases if the good is inferior, (4) the price of a substitute good rises, (5) the price of a complementary good falls, and (6) consumers expect a higher price in the future.

- The extent to which people will want to increase or decrease their purchases of a good in response to a change in its price is expressed by the concept of price elasticity of demand, which is the percentage change in the quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in the price.

- When the percentage change in quantity demanded is greater than the percentage change in price, demand is said to be elastic, and price changes will lead to changes in dollar expenditures on the good that move in the opposite direction from the price change. When the percentage change in the quantity demanded is less than the percentage change in the price, demand is said to be inelastic, and price changes will lead to changes in dollar expenditures on the good that move in the same direction as the price change.

- Just how sensitive are buyers to a change in price? The price elasticity of demand for a good depends primarily on the availability of substitutes. The better or more abundant the substitutes for a good, the greater will be the elasticity of the demand for it. Often it takes time to seek out and discover such substitutes, so time, too, plays a role in determining the price elasticity of demand. The more time people have to adjust to a higher price, the more elastic their response tends to be. Also, the proportion or percentage of one’s budget devoted to a good has an effect on elasticity. Consumers tend to be less sensitive to price changes for cheap and low-budget items, and more sensitive to the price changes of expensive, high-budget items.

- In markets people express their plans to obtain scarce goods and services by their willingness to reach agreements on prices. Although many different criteria can be and are used to determine who gets what, an economic system as a whole, which is based upon the voluntary exchange of private property rights, and by the criterion of money price, tends to enhance the economic freedom and power of individuals. Such rules, and the information signals they generate, allow people to calculate, and therefore better economize on the basis of the particular facts of their unique situation.