C15: Nursing Care of A Family During Labor and Birth

Labor is the series of events by which uterine contractions and abdominal pressure expel a fetus and placenta from the uterus. Regular contractions cause progressive dilatation of the cervix and create sufficient muscular uterine force to allow a baby to be pushed out into the extrauterine world.

Labor and birth are unique events, requiring a laboring person to employ all the psychological and physical coping methods they have available. Regardless of the amount of childbirth preparation or the number of times a person has been through the birth experience, family-centered nursing care is the approach that best supports them as they focus on the beginning of their new family. This goal for nursing is further emphasized by the Healthy People 2030 goals (Box 15.1).

Nursing Care Planning Based on Healthy People 2030 Goals

Because labor and birth are potentially high-risk times for both a fetus and a birthing parent, a number of Healthy People 2030 goals speak directly to these:

Reduce the rate of maternal deaths to no more than 15.7 out of 100,000 live births from a baseline of 17.4 out of 100,000 live births.

Reduce severe maternal complications identified during delivery hospitalizations from a baseline of 68.7 per 10,000 to 61.8 per 10,000.

Reduce cesarean births among low-risk (full-term, singleton, vertex presentation) patients from a baseline of 25.9% to a target of 23.6%.

Reduce the rate of fetal deaths at 20 or more weeks of gestation to no more than 5.9 out of 1,000 live births from a baseline of 5.7 out of 1,000.

Reduce the preterm birth rate from 10.0% to 9.45% (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020).

Nurses can help the nation achieve these goals by closely monitoring birthing parents during labor and birth and by teaching them as much as possible about labor so they are able to use as little analgesia and anesthesia as possible. The less anesthesia and analgesia used, the fewer complications that occur, resulting in reduced fetal or maternal death.

Nursing Process Overview: FOR THE PERSON IN LABOR

ASSESSMENT

A person in labor is keenly aware of both nonverbal and verbal expressions around them (i.e., not only words spoken but gestures such as eye rolling or sighing). Because of this sensitivity, an assessment must be done quickly yet thoroughly and gently because they may have difficulty being patient, for example, while admission information is obtained or relaxing for a vaginal examination.

Remember that pain is a subjective symptom. Only the patient can evaluate how much they are experiencing or how much they want to endure. Assess how much discomfort the patient is experiencing and how they feel about their labor not only by their score on a pain scale but also by subtle signs of pain such as facial tenseness, flushing or paleness of the face, hands clenched in a fist, rapid breathing, or rapid pulse rate. Appreciate that the fetus as well as the birthing parent is under stress from the process of labor, so both need vital sign assessments.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

Nursing diagnoses in labor generally relate to a patient's reaction to labor.

Common nursing diagnoses include:

Pain related to labor contractions

Anxiety related to process of labor and birth

Health-seeking behaviors related to management of discomfort of labor

Situational low self-esteem related to inability to use planned childbirth method

Although the discomfort of labor contractions is commonly referred to as "contractions" rather than "pain," do not omit the word "pain" from a nursing diagnosis because the term strengthens an understanding of the problem as well as alerts a patient they should feel free to ask for something for pain relief whenever they feel in need of additional help.

OUTCOME IDENTIFICATION AND PLANNING

When establishing expected outcomes for patients in labor and their partners, be certain they are realistic and that they can be met. Although labor usually takes place over a relatively short time frame (average, 12 hours), it is important not to project a definite time limit for labor to be completed because the length of labor can vary greatly and still be within normal limits. It is necessary also to appreciate the magnitude of labor. It is unlikely all the fear or anxiety experienced during labor can be completely alleviated. Often, because it is such an unusual and significant experience, the average patient may need guidance in order to be able to employ additional coping measures.

Be certain to incorporate a support person as well as the patient in planning so the experience is a shared one. Although people may have learned about the stages of labor and what to expect at each stage during pregnancy, the reality of labor may seem very different from what they imagined. Be certain also that planning is flexible and individualized, allowing patients to experience the full significance of the event.

IMPLEMENTATION

As much as possible, interventions during labor should always be carried out between contractions so the patient can use pain management techniques to limit the discomfort of contractions. This calls for good coordination of care among healthcare providers and the patient and their support person. The person a patient chooses to stay with them during childbirth is often culturally determined and varies from being a spouse, a significant other or partner, the non birthing parent of the child, a sibling, a parent, or a close friend.

OUTCOME EVALUATION

An evaluation during labor should be ongoing to preserve the safety of the patient and the newborn. After birth, an evaluation helps to determine the patient's opinion of their experience with labor and birth. Ideally, the experience should not only be one they could endure but also one that allowed their self-esteem to grow and the family bond to intensify through a shared experience. It is advantageous to talk to patients following birth about their labor experience because doing so serves as a means of evaluating nursing care during labor. It also provides a patient the chance to work through" the experience and incorporate it into their self-image.

Possible outcome criteria include:

Patient states pain during labor was tolerable because of their advanced preparation.

Patient verbalizes that the need for nonpharmacologic comfort measures was met.

Patient and family members state the labor and birth experience was a positive growth experience for them, both individually and as a family.

Theories of Why Labor Begins

Labor normally begins between 37 and 42 weeks of pregnancy, when a fetus is sufficiently mature to adapt to extrauterine life, yet not too large to cause mechanical difficulty with birth. In some instances, labor begins before a fetus is mature (preterm birth). In others, labor is delayed until the fetus and the placenta have both passed beyond the optimal point for birth (post term birth).

A number of factors are known to be responsible for the initiation of spontaneous labor, although much is still unknown. Factors such as withdrawal of progesterone, an increase of prostaglandins, and other complex biochemical markers have shown to be at work (Cunningham et al., 2018). A number of theories, including a combination of factors originating from both the parent and fetus, have been proposed to explain why progesterone withdrawal begins. Some of the theories include:

The uterine muscle stretches from the increasing size of the fetus, which results in release of prostaglandins.

The fetus presses on the cervix, which stimulates the release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary.

Oxytocin stimulation works together with prostaglandins to initiate contractions.

Changes in the ratio of estrogen to progesterone occur increasing estrogen in relation to progesterone, which is interpreted as progesterone withdrawal.

The placenta reaches a set age, which triggers contractions.

Rising fetal cortisol levels reduce progesterone formation and increase prostaglandin formation.

The fetal membrane begins to produce prostaglandins, which stimulate contractions (Cunningham et al., 2018)

The role of prostaglandins answers the often-asked question: Does coitus help induce labor? Semen does contain prostaglandins, which can be helpful in softening, also known as "ripening" of the cervix; if a cervix is ready to ripen, semen prostaglandins could possibly stimulate the beginning of contractions. Rhythmic contractions brought on by female orgasm can conceivably help as well, although, again, not until a uterus is prepared and ready for labor.

The Components of Labor

A successful labor depends on four integrated concepts, often referred to as the four Ps:

The passage (pelvis) is of adequate size and contour.

The passenger (the fetus) is of appropriate size and in an advantageous position and presentation

The powers of labor (uterine factors) are adequate.

The psyche, or psychological state, which may either encourage or inhibit labor. This can be based on the pregnant person's past life experiences as well as present psychological state.

THE PASSAGE

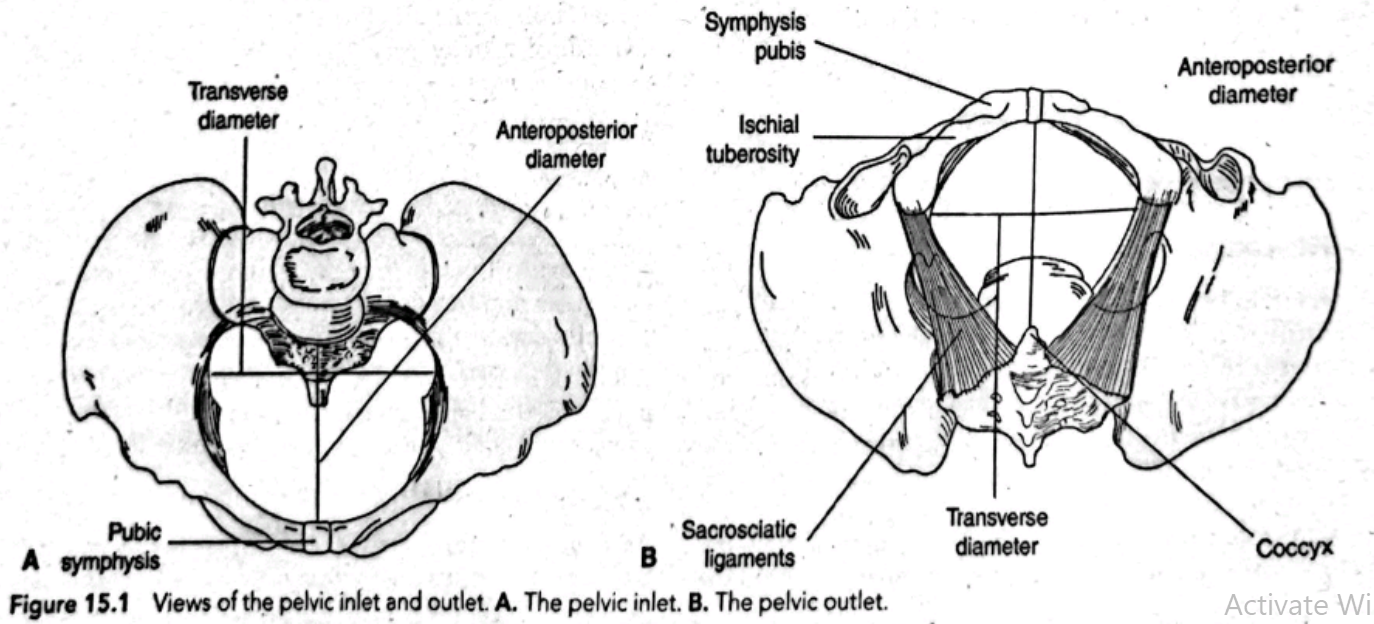

The passage refers to the route a fetus must travel from the uterus through the cervix and vagina to the external perineum (Fig. 15.1).

In most instances, if a disproportion between fetus and pelvis occurs, the pelvis is the structure at fault. If the fetus is the cause of the disproportion, it is often not because the fetal head is too large but because it is presenting to the birth canal at less than its narrowest diameter. Keep this in mind when discussing with parents why an infant may not be able to be born vaginally. It can be upsetting for parents to learn that a child cannot be born vaginally because the birthing parent's pelvis is too small. It can be much more upsetting to think their infant's head is too large because it implies something may be seriously wrong with their baby (and that is rarely true). Avoiding this type of negative thought helps promote good parent-child bonding.

THE PASSENGER

The passenger is the fetus. The body part of the fetus that has the widest diameter is the head, so this is the part least likely to be able to pass through the pelvic ring. Whether a fetal skull can pass depends on both its structure (bones, fontanelles, and suture lines) and its alignment with the pelvis.

Structure of the Fetal Skull

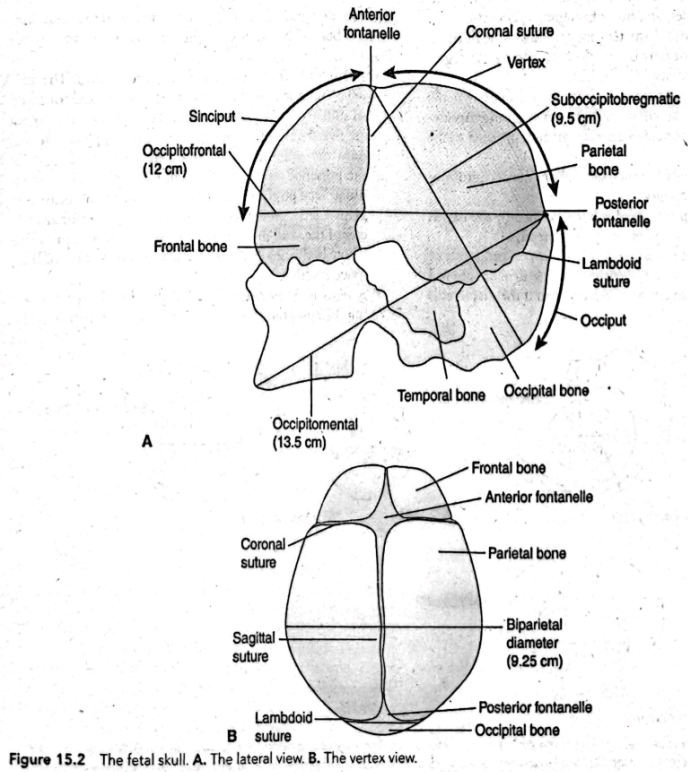

The cranium, the uppermost portion of the skull, is composed of eight bones. The four superior bones-the frontal (actually two fused bones), the two parietal, and the occipital-are the bones important in childbirth. The other four bones of the skull (sphenoid, ethmoid, and two temporal bones) lie at the base of the cranium and so are of little significance in child-birth because they are never presenting parts (Fig. 15.2).

Fontanelle spaces compress during birth to aid in molding of the fetal head. Their presence can be assessed manually through the cervix after the cervix has dilated during labor. Palpating for fontanelle spaces during a pelvic examination helps to establish the position of the fetal head and whether it is in a favorable position for birth.

Diameters of the Fetal Skull

The shape of a fetal skull causes it to be wider in its anteroposterior diameter than in its transverse diameter. To fit through the inlet of the birth canal best, a fetus must present the smaller diameter (the transverse diameter) of the head to the smaller diameter of the maternal pelvis (the diagonal conjugate); otherwise, progress can be halted and vaginal birth may not be possible. The diameters of the fetal skull vary depending on where the measurement is taken (Fig. 15.2A).

The smallest diameter of the fetal skull is the biparietal diameter or the transverse diameter, which measures about 9.25 cm.

The smallest anteroposterior diameter is the suboccipitobregmatic measurement (approximately 9.5 cm) and is measured from the inferior aspect of the occiput to the center of the anterior fontanelle.

The occipitofrontal diameter, measured from the occipital prominence to the bridge of the nose, is approximately 12 cm.

The occipitomental diameter, which is the widest anteroposterior diameter (approximately 13.5 cm), is measured from the posterior fontanelle to the chin.

The anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis, a space approximately 11 cm wide, is the narrowest diameter at the pelvic inlet, and so the best presentation for birth is when the fetus presents a biparietal diameter (the narrowest fetal head diameter) to this (see Fig. 15.2B). At the outlet, the fetus must rotate to present this narrowest fetal head diameter (the biparietal diameter) to the maternal transverse diameter, a space, again, approximately 11 cm wide.

If a fetus presents one of the anteroposterior diameters of the skull to the anteroposterior diameter of the inlet, engagement, or the settling of the fetal head into the pelvis, may not occur.

If the fetus does not rotate, leaving the anteroposterior diameter of the skull presenting to the transverse diameter of the outlet, an arrest of progress may occur.

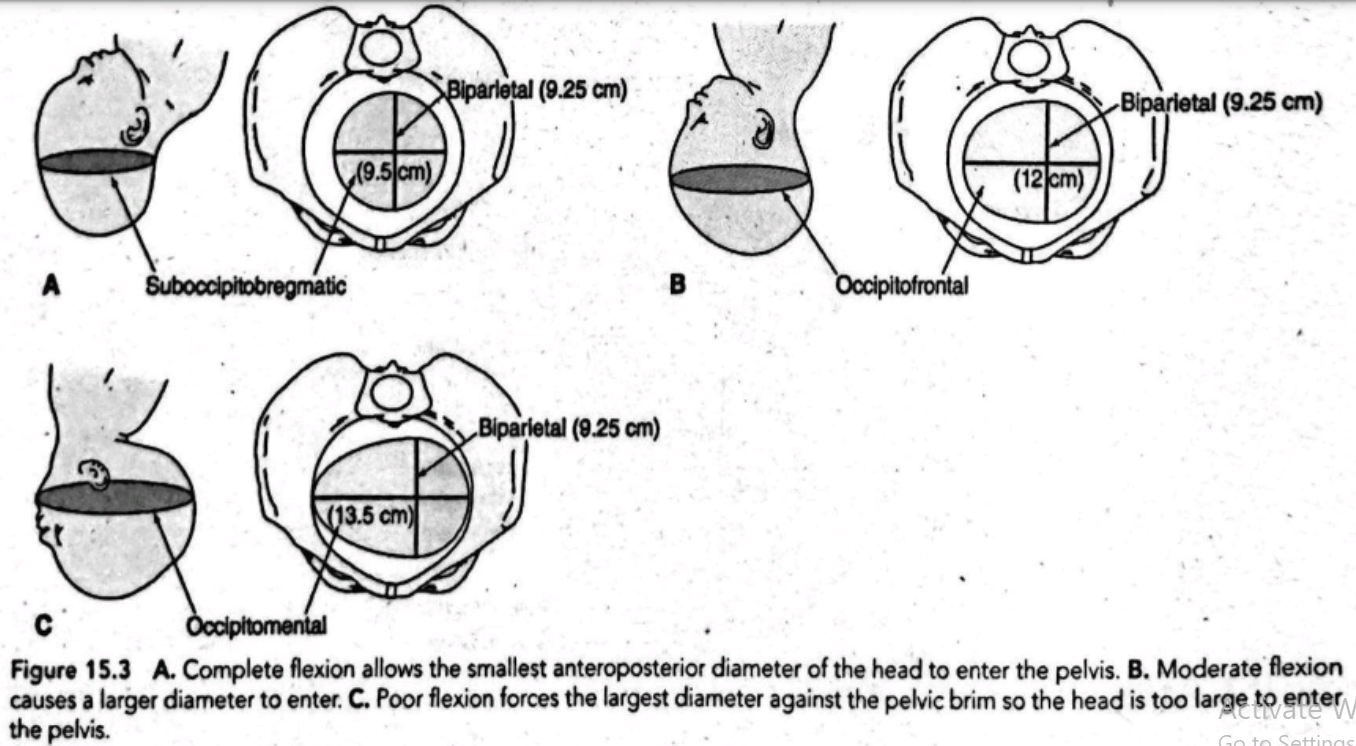

The anteroposterior diameter that presents to the birth canal is determined not only by rotation but also by the degree of flexion of the fetal head (Fig. 15.3).

In full flexion, the fetal head flexes so sharply that the chin rests on the chest, and the smallest anteroposterior diameter, the suboccipitobregmatic, presents to the birth canal.

If the head is held in moderate flexion, the occipitofrontal diameter presents.

In poor flexion (the head is hyperextended), the largest diameter (the occipitomental) will present.

It follows that full head flexion is an important aspect of labor because a fetal head presenting a diameter of 9.5 cm will fit through a pelvis much more readily than if the diameter is 12.0 or 13.5 cm.

Molding

Molding is overlapping of skull bones along the suture lines, which causes a change in the shape of the fetal skull to one long and narrow, a shape that facilitates passage through the rigid pelvis. Molding is caused by the force of uterine contractions as the vertex of the head is pressed against the not-yet-dilated cervix. The overlapping that occurs in the sagittal suture line and, generally, the coronal suture line can be easily palpated on the newborn skull. Parents can be reassured that molding only lasts a day or two and will not be a permanent condition. There is little molding when the brow is the presenting part (described later) because frontal bones are fused. No skull molding occurs when a fetus is breech because the buttocks, not the head, present first. Babies born by cesarean birth when there is no labor also typically have no molding.

Fetal Attitude and Lie

Other factors that play a part in whether a fetus is properly aligned in the pelvis and is in the best position to be born are fetal attitude, fetal lie, fetal presentation, and fetal position.

Fetal Attitude

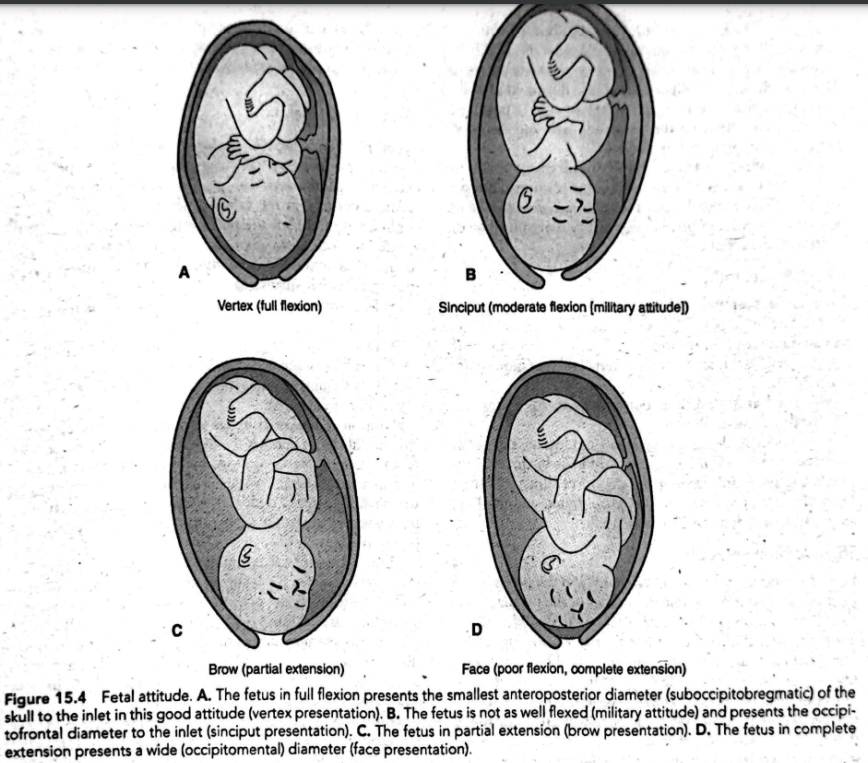

Attitude describes the degree of flexion a fetus assumes during labor or the relation of the fetal parts to each other (Fig. 15.4).

A fetus in optimal attitude is in complete flexion: The spinal column is bowed forward, the head is flexed forward so much that the chin touches the sternum, the arms are flexed and folded on the chest, the thighs are flexed onto the abdomen, and the calves are pressed against the posterior aspect of the thighs (see Fig. 15.4A). This usual "fetal position" is advantageous for birth because it helps a fetus present the smallest anteroposterior diameter of the skull to the pelvis and also because it puts the whole body into an ovoid shape, occupying the smallest space possible.

A fetus is in moderate flexion if the chin is not touching the chest but is in an alert or "military position" (see Fig. 15.4B). This position causes the next widest antero- posterior diameter, the occipitofrontal diameter, to present to the birth canal. A fair number of fetuses assume a military position early in labor. This does not usually interfere with labor, however, because later mechanisms of labor (descent and flexion) force the fetal head to fully flex.

A fetus in partial extension presents the "brow" of the head to the birth canal (see Fig. 15.4C).

If a fetus is in complete extension, the back is arched and the neck is extended, presenting the occipitomental diameter of the head to the birth canal (a face presentation; see Fig. 15.4D). This unusual position usually presents too wide a skull diameter to the birth canal for vaginal birth. Such a position may occur. in an otherwise healthy fetus or may be an indication there is less than the usual amount of amniotic fluid present (oligohydramnios), which is not allowing the fetus adequate movement space. It also may reflect a neurologic abnormality in the fetus, causing spasticity.

Fetal Lie

Lie is the relationship between the long (cephalocaudal) axis of the fetal body and the long (cephalocaudal) axis of a female's body-in other words, whether the fetus is lying in a horizontal (transverse) or a vertical (longitudinal) position. Approximately 96% of fetuses assume a longitudinal lie (with their long axis parallel to the long axis of the parent) (King et al., 2019).

Longitudinal lies are further classified as cephalic, which means the fetal head will be the first part to contact the cervix, or breech, with a foot or the buttocks as the first portion to contact the cervix.

Fetal Presentation

Fetal presentation denotes the body part that will first contact the cervix or be born first and is determined by the combination of fetal lie and the degree of fetal flexion (attitude).

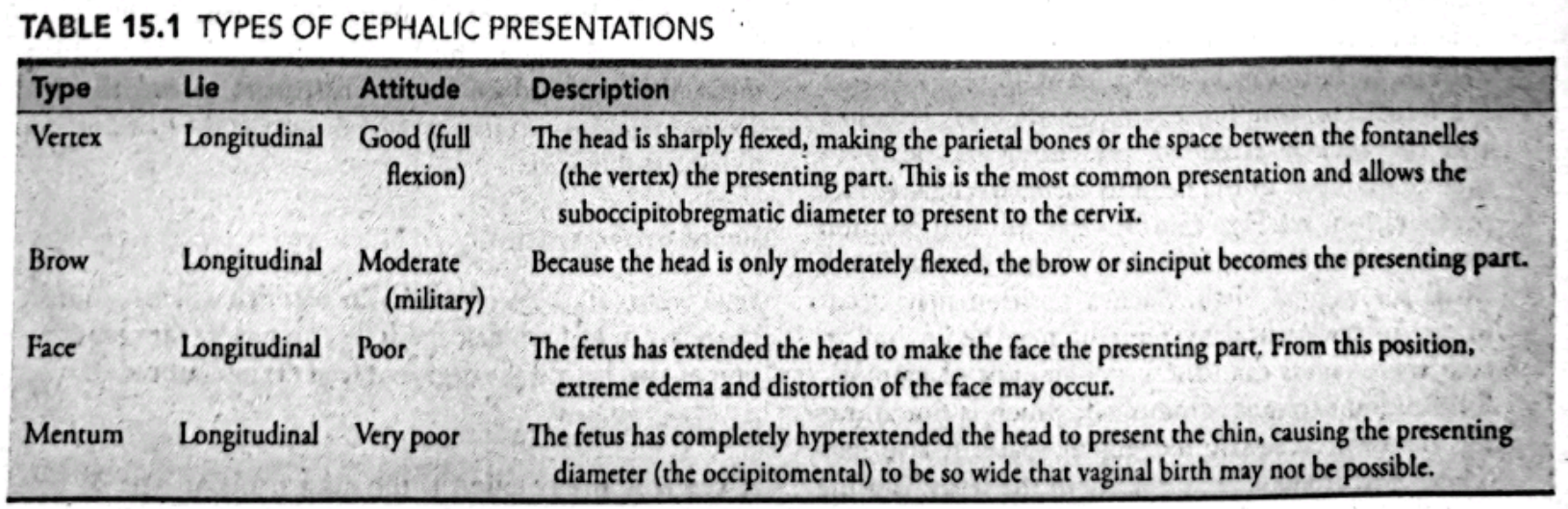

Cephalic Presentation

A cephalic presentation is the most frequent type of presentation, occurring as often as 96% of the time. With this type of presentation, the fetal head is the body part that first contacts the cervix. The four types of cephalic presentation (vertex, brow, face, and mentum) are described in Table 15.1. The vertex is the ideal presenting part because the skull bones are capable of effectively molding to accommodate the cervix. This exact fit may actually aid in cervical dilatation as well as prevent complications such as a prolapsed cord (a portion of the cord passes between the presenting part and the cervix and enters the vagina before the fetus).

During labor, the area of the fetal skull that contacts the cervix often becomes edematous from the continued pressure against it. This edema is called a caput succedaneum. In the newborn, the point of presentation can be determined by the location of the caput.

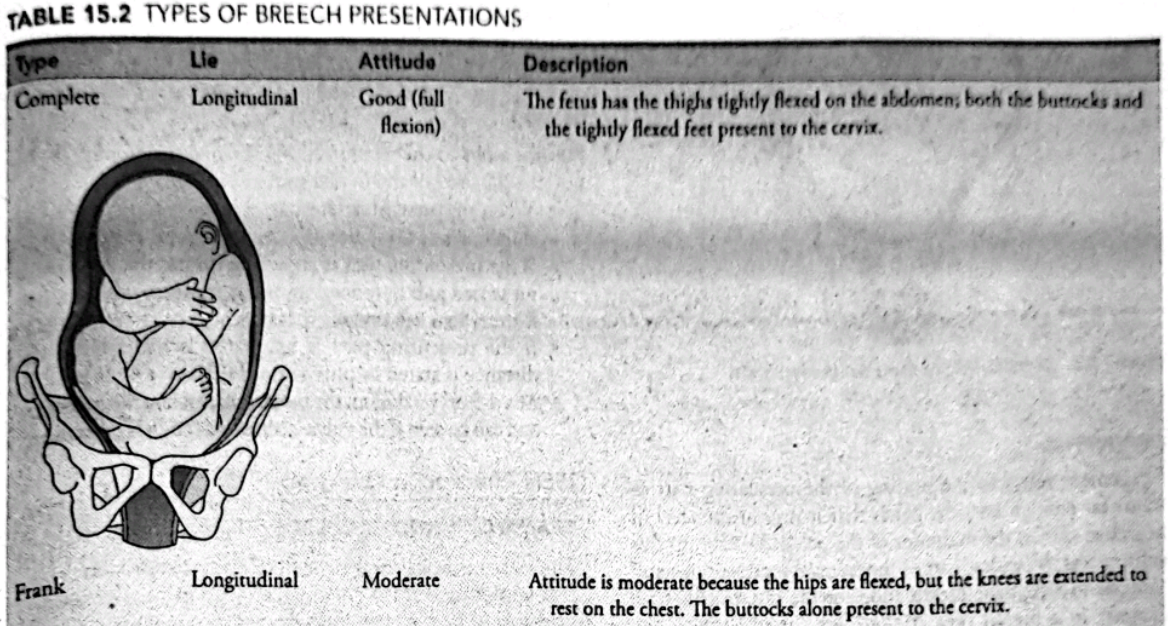

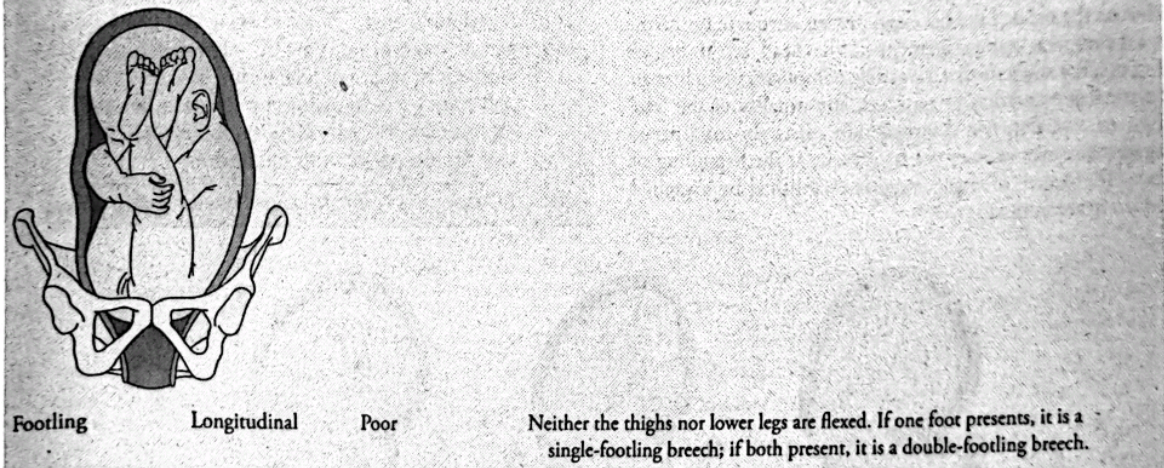

Breech Presentation

A breech presentation means either the buttocks or the feet. are the first body parts that will contact the cervix. Breech presentations occur in approximately 4% of births and are affected by fetal attitude the same as vertex presentations (King et al., 2019).

A good attitude brings the fetal knees up against the fetal abdomen.

A poor attitude means the knees and legs are extended.

Breech presentation can cause a difficult birth, with the presenting point influencing the degree of difficulty. Three types of breech presentation (complete, frank, and footling) are possible and described in Table 15.2.

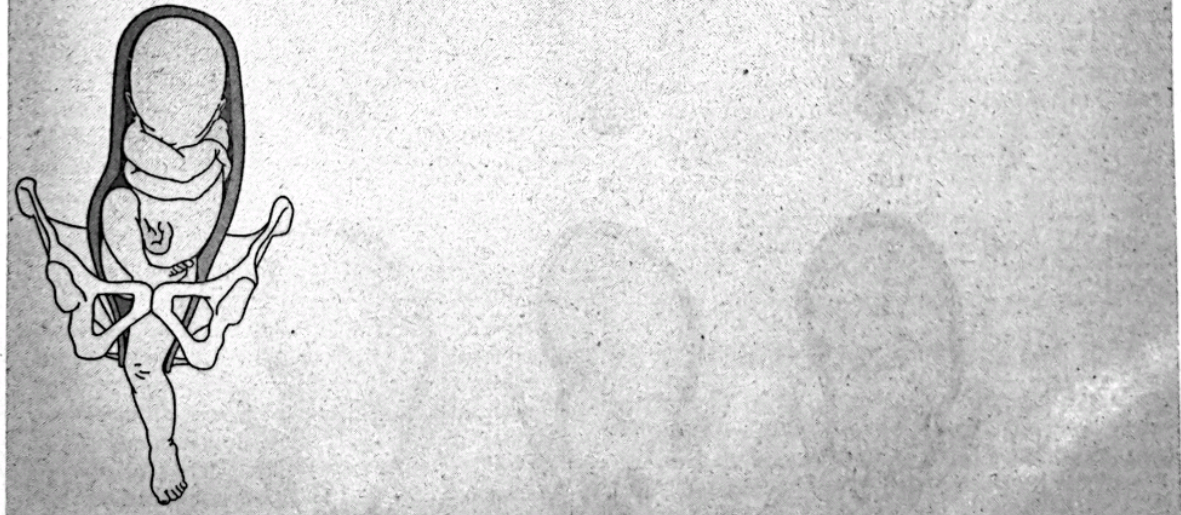

Shoulder Presentation

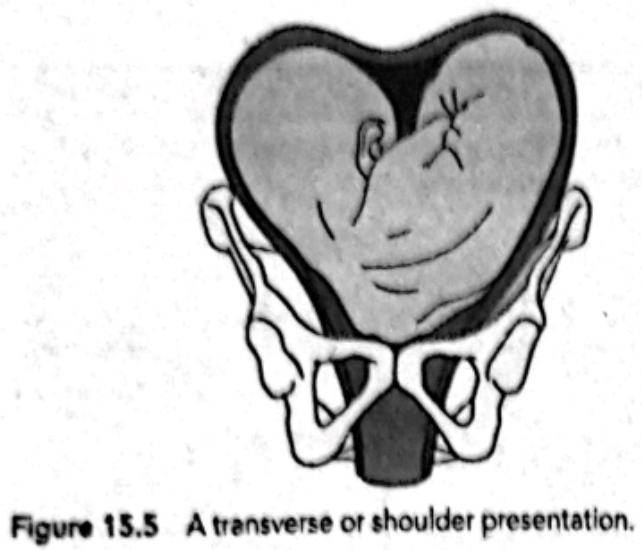

In a transverse lie, a fetus lies horizontally in the pelvis so the longest fetal axis is perpendicular to that of the pregnant person. The presenting part is usually one of the shoulders (acromion process), an iliac crest, a hand, or an elbow (Fig. 15.5). The usual contour of the pregnant person's abdomen at term may appear fuller side to side rather than top to bottom.

Fewer than 1% of fetuses lie transversely. This presentation may be caused by pelvic contractions, in which the horizontal space is greater than the vertical space or by the presence of a placenta previa (the placenta is located low in the uterus, ob- scuring some of the vertical space). It also can be caused by re- laxed abdominal walls from grand multiparity, which allows the unsupported uterus to fall forward (King et al., 2019).

If an infant is preterm and smaller than usual, an attempt to turn the fetus to a horizontal lie (external fetal version) may be made. Most infants in a transverse lie must be born by cesarean birth, however, because they can neither be turned nor born vaginally due to this "wedged" position. Discovering a shoulder presentation during labor is an important assess ment because it almost always identifies a birth position tha puts both birthing parent and child in jeopardy unless skilled healthcare personnel are available to complete a cesarean birth

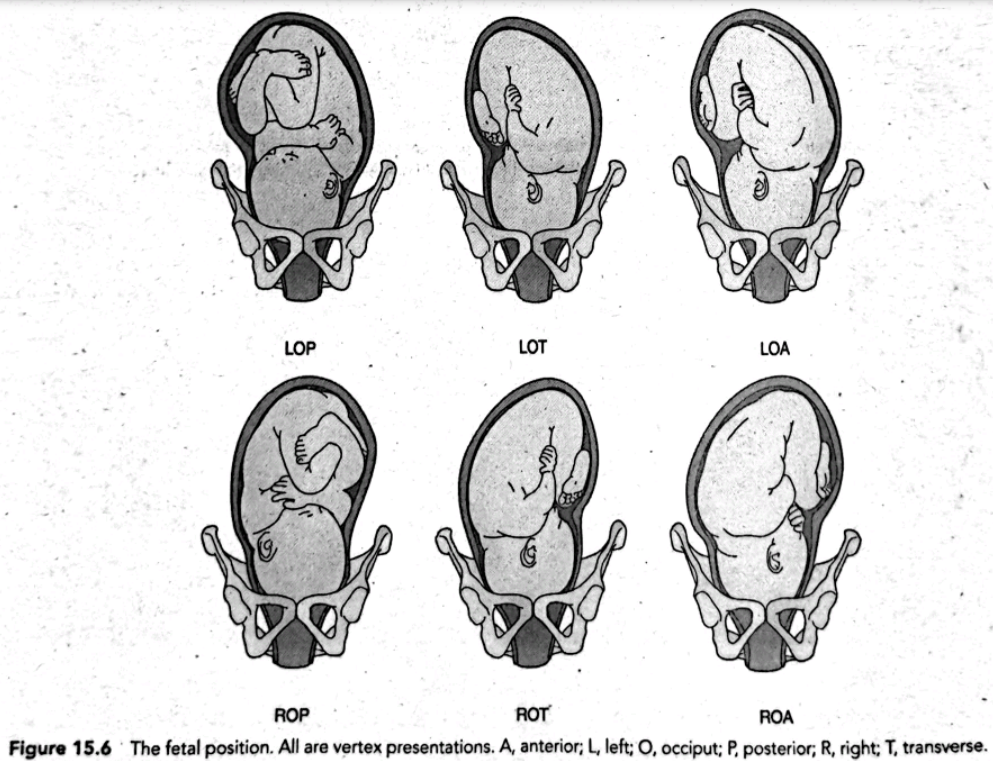

Fetal Position

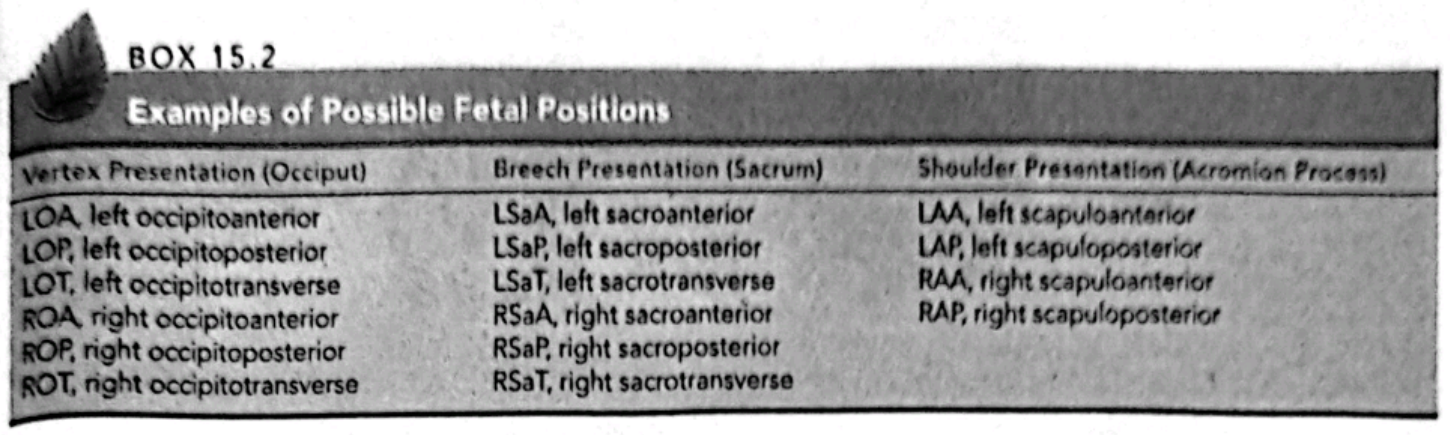

Fetal position is the relationship of the presenting part to a specific quadrant and side of the pregnant person's pelvis. For convenience, the maternal pelvis is divided into four quad rants according to the birthing person's right and left: (a) right anterior, (b) left anterior, (c) right posterior, and (d) left posterior. Four parts of a fetus are typically chosen as land- marks to describe the relationship of the presenting part to one of the pelvic quadrants.

In a vertex presentation, the occiput (O) is the chosen point.

In a face presentation, it is the chin (mentum [M]). In a breech presentation, it is the sacrum (Sa).

In a shoulder presentation, it is the scapula or the acromion process (A).

Position is indicated by an abbreviation of three letters. The middle letter denotes the fetal landmark (O for occiput, M for mentum, Sa for sacrum, and A for acromion process). The first letter defines whether the landmark is pointing to the birthing parent's right (R) or left (L). The last letter de- fines whether the landmark points anteriorly (A), posteriorly (P), or transversely (T).

If the occiput of a fetus points to the left anterior quadrant in a vertex position, for example, this is a left occipitoanterior (LOA) position. If the occiput points to the right posterior quadrant, the position is right occipitoposterior (ROP). LOA is the most common fetal position, and right occipitoanterior (ROA) is the second most frequent. Box 15.2 summarizes possible positions. Six common positions in cephalic presen- tations are illustrated in Figure 15.6.

Position is important because it can influence both the process and efficiency of labor. Typically, a fetus is born fast- est from an ROA or LOA position. Labor can be considerably extended if the position is posterior (ROP or LOP) and may be more painful because the rotation of the fetal head puts pressure on sacral nerves. Encouraging a patient to rest in a Sims position on the same side as the fetal spine or use a hands-and-knees position may encourage rotation from an occipitoposterior to an occipitoanterior position prior to and during labor (Bueno-Lopez et al., 2018).

Engagement

Engagement refers to the settling of the presenting part of a fecus far enough into the pelvis that it rests at the level of the ischial spines, the midpoint of the pelvis. Descent to this point means the widest part of the fetus (the presenting skull diameter in a cephalic presentation, or the intertrochanteric diameter in a breech presentation) has passed through the pelvis or the pelvic inlet has been proven adequate for birth. In a primipara, nonengagement of the head at the begin- ning of labor suggests that a possible complication such as an abnormal presentation or position, abnormality of the fetal head, or cephalopelvic disproportion exists. In multiparas, engagement may or may not be present at the beginning of labor. The degree of engagement is established by a vaginal and cervical examination.

A presenting part that is not engaged is said to be "floating"

One that is descending but has not yet reached the ischial spines may be referred to as "dipping"

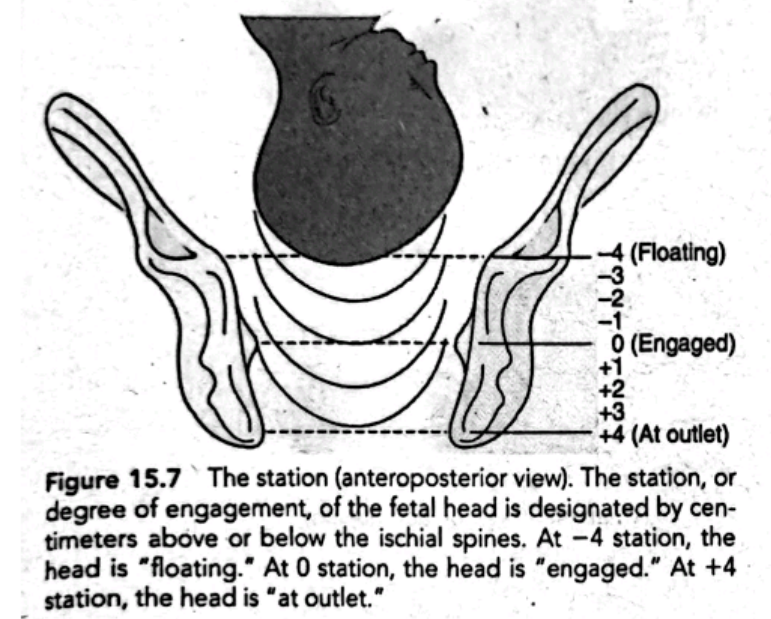

Station

Station refers to the relationship of the presenting part of the fetus to the level of the ischial spines (Fig. 15.7).

When the presenting fetal part is at the level of the ischial spines, it is at a O station (synonymous with engagement

If the presenting part is above the spines, the distance is measured and described as minus stations, which range from -1 to -4 cm.

If the presenting part is below the ischial spines, the distance is stated as plus stations (+1 to +4 cm).

At a +3 or +4 station, the presenting part is at the perineum and can be seen if the vulva is separated (ie., it is crowning

Mechanisms (Cardinal Movements) of Labor

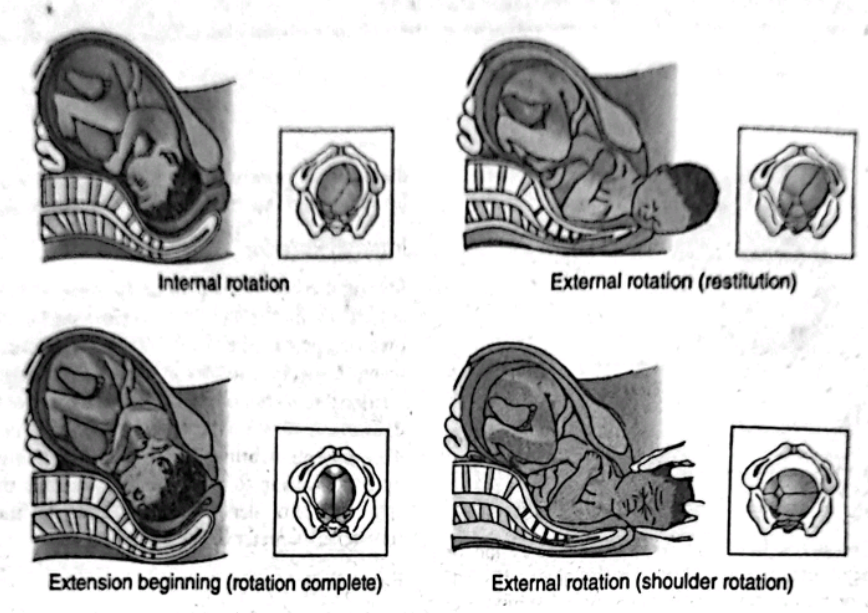

Effective passage of a fetus through the birth canal involves not only position and presentation but also a number of dif- ferent position changes in order to keep the smallest diameter of the fetal head (in cephalic presentations) always presenting to the smallest diameter of the pelvis. These position changes are termed the cardinal movements of labor: descent, flexion, internal rotation, extension, external rotation, and expulsion (Fig. 15.8).

Descent

Descent is the downward movement of the biparietal diam- eter of the fetal head within the pelvic inlet. Full descent oc- curs when the fetal head protrudes beyond the dilated cervix and touches the posterior vaginal floor. Descent occurs be- cause of pressure on the fetus by the uterine fundus. As the pressure of the fetal head presses on the sacral nerves at the pelvic floor, the pregnant person will experience the typical "pushing sensation," which occurs with labor. This pushing, which contracts the abdominal muscles, aids descent.

Flexion

As descent is completed and the fetal head touches the pelvic floor, the head bends forward onto the chest, causing the smallest anteroposterior diameter (the suboccipitobregmatic diameter) to present to the birth canal. Flexion is also aided by abdominal muscle contraction during pushing.

Internal Rotation

During descent, the biparietal diameter of the fetal skull was aligned to fit through the anteroposterior diameter of the pregnant person's pelvis. As the head flexes at the end of de- scent, the occiput rotates so the head is brought into the best relationship to the outlet of the pelvis, or the anteroposterior diameter is now in the anteroposterior plane of the pelvis. This movement brings the shoulders, coming next, into the optimal position to enter the inlet, or puts the widest diam- eter of the shoulders (a transverse one) in line with the wide transverse diameter of the inlet.

Extension

As the occiput of the fetal head is born, the back of the neck stops beneath the pubic arch and acts as a pivot for the rest of the head. The head extends, and the foremost parts of the head, the face and chin, are born.

External Rotation

In external rotation, almost immediately after the head of the in- fant is born, the head rotates a final time (from the anteroposte rior position it assumed to enter the outlet) back to the diagonal or transverse position of the early part of labor. This brings the after coming shoulders into an anteroposterior position, which is best for entering the outlet. The anterior shoulder is born first, assisted perhaps by downward flexion of the infant's head.

Expulsion

Once the shoulders are born, the rest of the baby is born eas- ily and smoothly because of its smaller size. This movement, called expulsion, is the end of the pelvic division of labor. For a view of the complete birth sequence, see Figure 15.9.

THE POWERS OF LABOR

The third important requirement for a successful labor is ef- fective powers of labor. This is the force supplied by the fun- dus of the uterus and implemented by uterine contractions, which causes cervical dilatation and then expulsion of the fetus from the uterus. After full dilatation of the cervix, the primary power is supplemented by use of a secondary power source, the abdominal muscles. It is important for patients to understand that they should not bear down with their abdominal muscles to push until the cervix is fully dilated.

Doing so impedes the primary force and could cause fetal and cervical damage.

Uterine Contractions.

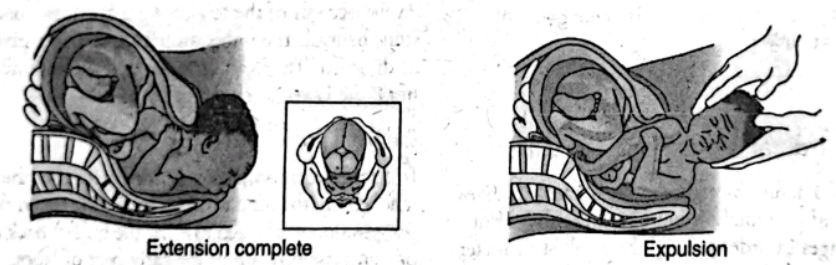

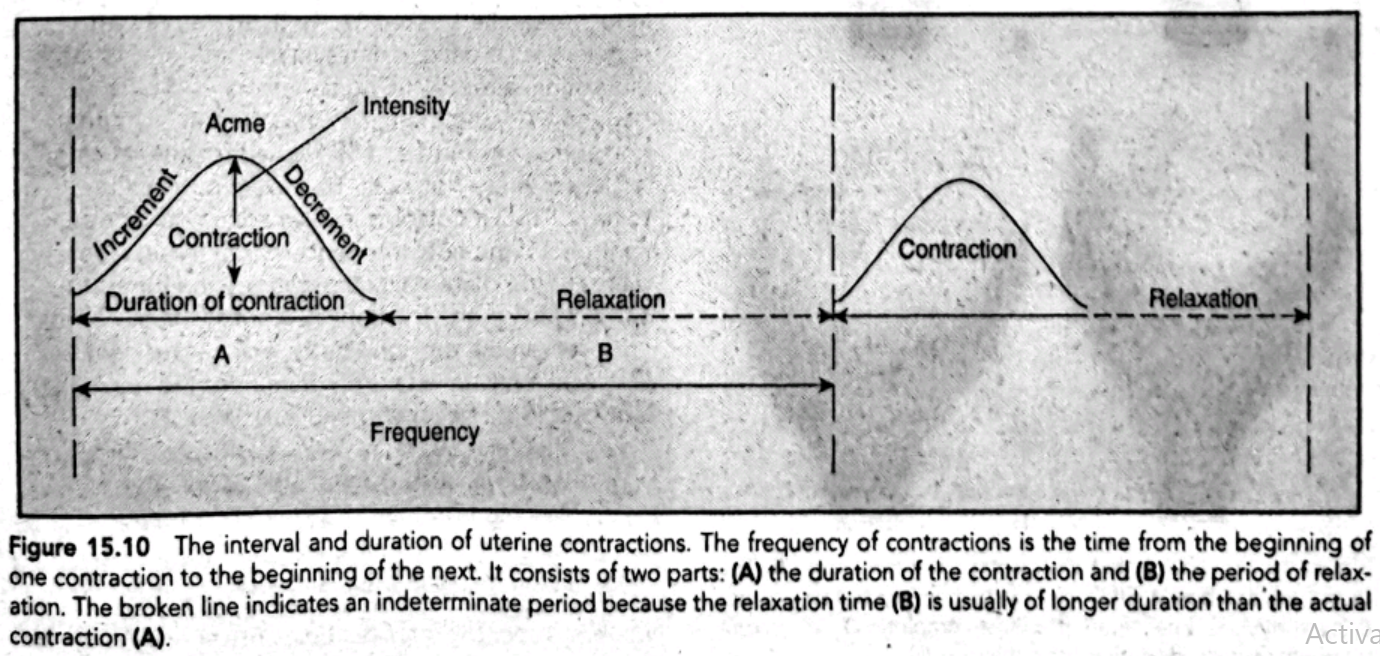

During pregnancy, the uterus begins to contract and relax periodically as if it is rehearsing for labor (Braxton Hicks con- tractions, or false labor). These contractions are usually mild but can be strong enough to be mistaken for true labor. As a rule, even if a patient thinks what they are feeling cannot be true labor, they should contact the primary care provider to have the contractions further evaluated to rule out preterm labor. The mark of Braxton Hicks contractions is that they are usually irregular and are painful, but they do not cause cervical dilatation. In contrast, effective uterine contractions have rhythmicity, a progressive increase in length and intensity, and accompany dilatation of the cervix. These differences between false and true labor are summarized in Table 15.3. Contractions are assessed according to frequency, duration, and strength.

Origins

Like cardiac contractions, labor contractions begin at a "pace- maker" point located in the uterine myometrium near one of the uterotubal junctions. Each contraction begins at that point and then sweeps down over the uterus as a wave. After a short rest period, another contraction is initiated and the downward sweep begins again.

In early labor, the uterotubal pacemaker may not operate in a synchronous manner. This makes contractions sometimes strong, sometimes weak, and somewhat irregular. This mild incoordination of early labor improves after a few hours as the pacemaker becomes more attuned to calcium concentrations in the myometrium and begins to function effectively.

In some patients, contractions appear to originate in the lower uterine segment rather than in the fundus. These are reversed and ineffective and may actually cause tightening rather than dilatation of the cervix. It is difficult to tell from palpation that contractions are being initiated in a reverse pattern. It can be suspected, however, if the patient reports feeling pain in their lower abdomen before the contraction is readily palpated at the fundus. It is truly revealed only when apparently strong uterine contractions do not cause cervical dilatation.

Some patients seem to have additional pacemaker sites in other portions of the uterus. This may cause uncoordinated contractions that can slow labor and lead to failure to prog- ress and fetal distress because they may not allow for adequate placental filling. All of these possibilities make evaluating the rate, intensity, and pattern of uterine contractions an impor- tant nursing responsibility.

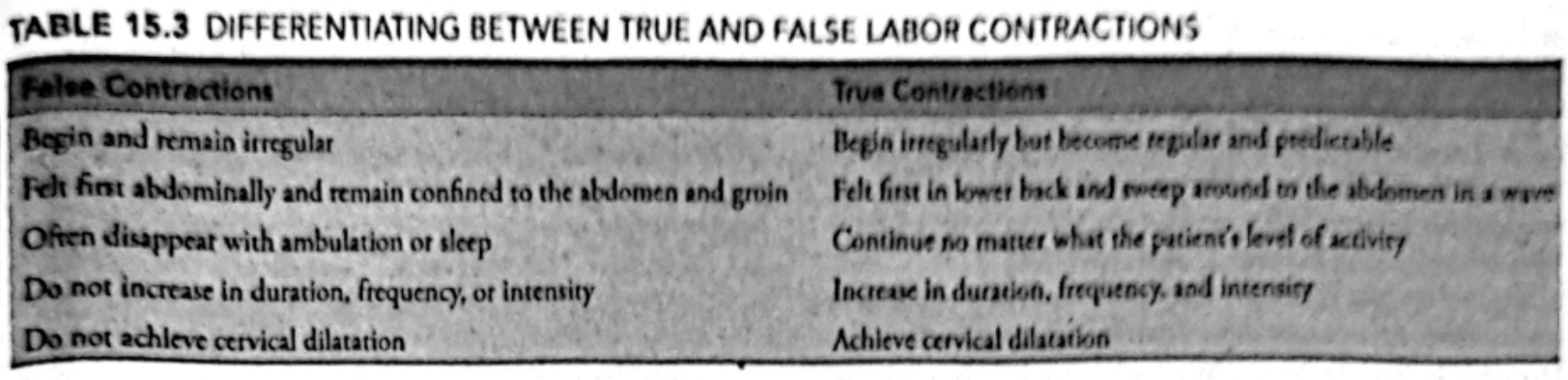

Phases

A contraction consists of three phases: the increment, when the intensity of the contraction increases; the acme, when the contraction is at its strongest; and the decrement, when the intensity decreases (Fig. 15.10). Between contractions, the uterus relaxes. As labor progresses, the relaxation intervals decrease from 10 minutes early in labor to only 2 to 3 minutes. The duration of contractions also changes, increasing from 20 to 30 seconds at the beginning to a range of 60 to 70 seconds by the end of the first stage (Cunningham et al., 2018).

Contour Changes

As labor contractions progress and become regular and strong, the uterus gradually differentiates itself into two dis- tinct functioning areas: an upper portion, which thickens, and a lower segment, which becomes thin-walled, supple, and passive so the fetus can be pushed out of the uterus easily. The contour of the overall uterus also changes from a round, ovoid structure to an elongated one with a vertical diameter markedly greater than the horizontal diameter. This lengthening straightens the body of the fetus, bringing it into better alignment with the cervix and pelvis. The elongation of the uterus can cause pressure against the diaphragm and leads to the often expressed sensation that a uterus is "taking control" of a pregnant person's body.

Cervical Changes

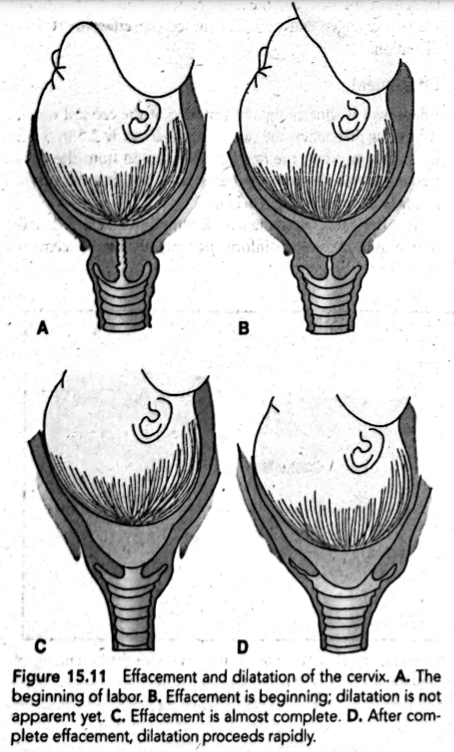

Even more marked than the changes in the body of the uterus are two changes that occur in the cervix: effacement and dilatation.

Effacement

Effacement is shortening and thinning of the cervical canal. All during pregnancy, the canal is approximately 2.5 to 5 cm long. During labor, the longitudinal traction from the con- tracting uterus shortens the cervix so much that the cervix virtually disappears (Fig. 15.11).

In primiparas, effacement is accomplished before dilata- tion begins. Be sure to inform patients of both effacement and dilatation following a pelvic examination. If a patient is told at noon, for example, they are 3 cm dilated and then at 4 p.m., told they are still 3 cm dilated, it is a discouraging report because it seems as if absolutely nothing has happened in 4 hours. Effacement, however, will have been occurring: sharing this information as well can be the necessary encour agement to continue working with contractions.

In multiparas, dilatation may proceed before effacement is complete. Effacement must occur by the end of dilatation, however, before the fetus can be safely pushed through the cervical canal; otherwise, cervical tearing can result.

Dilatation

Dilatation refers to the enlargement or widening of the cervi- cal canal from an opening a few millimeters wide to one large enough (approximately 10 cm) to permit passage of a fetus (see Fig. 15.11).

Dilatation occurs first because uterine contractions gradu- ally increase the diameter of the cervical canal lumen by pulling the cervix up over the presenting part of the fetus. Secondly, the fluid-filled membranes push ahead of the fetus and serve as an opening wedge. If they are ruptured, the pre- senting part will serve this same function, although maybe not as effectively.

As dilatation begins, there is an increase in the amount of vaginal secretions (show) because minute capillaries in the cervix rupture and the last of the mucus plug that has sealed the cervix since early pregnancy is released.

THE PSYCHE

The fourth "P," or psychological outlook, refers to the psycho logical state or feelings a pregnant person brings into labor For many, this is a feeling of apprehension or fright.. For al most everyone, it includes a sense of excitement or awe.

Those who manage best in labor typically have a strong sense of self-esteem and a meaningful support person with them. These factors allow pregnant people to feel in control of sensa tions and circumstances they have never experienced before and which may not be what they expected (Bohren et al., 2017). Pregnant people without adequate support can have a labor experience so frightening and stressful that they develop symp toms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Ayers, 2017).

Encourage patients to ask questions at prenatal visits and to attend preparation for childbirth classes so they are as well pre- pared for labor as possible. Encourage them after birth to talk about and share their experience because a "debriefing time" can be an important way to help them appreciate everything that happened and integrate the experience into their total life.

The Stages of Labor

Labor is traditionally divided into three stages:

The first stage of dilatation, which begins with the initiation of true labor contractions and ends when the cervix is fully dilated

The second stage, extending from the time of full dilatation until the infant is born

The third or placental stage, lasting from the time the infant is born until after the delivery of the placenta

The first 1 to 4 hours after birth of the placenta is sometimes termed the "fourth stage" to emphasize the importance of close maternal observation needed at this time.

THE FIRST STAGE

The first stage, which takes about 12 hours to complete, is divided into three segments: a latent, an active, and a transition phase. Traditionally the Freidman's curve, an algorithm for determining normal labor progress, has been utilized in labor settings everywhere. However, new research is discovering that a normal labor can actually take a great deal longer than previously thought (Cohen & Friedman, 2018).

The Latent Phase

The latent or early phase begins at the onset of regularly perceived uterine contractions and ends when rapid cervical dilatation begins. Contractions during this phase are mild and short, lasting 20 to 40 seconds. Cervical effacement occurs, and the cervix dilates minimally. A birthing parent who is multiparous usually progresses more quickly than a nullipara. A birthing parent who enters labor with a "nonripe" cervix will probably have a longer than average latent phase. If a patient wants analgesia at this point, they shouldn't be denied it, as the previous belief that analgesia prolongs the first stage of labor is not well supported by evidence.

In a patient who is psychologically prepared for labor and who does not tense at each tightening sensation in their abdomen, latent phase contractions cause only minimal discomfort and can be managed by controlled breathing. During this phase, encourage patients to continue to walk about and make preparations for birth, such as doing last-minute packing for their stay at the hospital or birthing center, preparing older children for their departure and the upcoming birth, or giving instructions to the person who will take care of them while they are away. If desired, they could begin alternative methods of pain relief such as aromatherapy, distraction, or acupressure (Babbar et al., 2017). If the patient should come to a birthing setting this early, encourage them to continue to be active and to use any nonpharmacotherapeutic measures they find effective.

The Active Phase

The active phase of labor is considered to begin at 6 cm (Cohen & Friedman, 2018). During the active phase, cervical dilatation occurs more rapidly. Contractions grow stronger, lasting 40 to 60 seconds, and occur approximately every 3 to 5 minutes. Show (increased vaginal secretions) and, perhaps, spontaneous rupture of the membranes may occur during this time. Encourage patients to be active participants in labor by keeping active and assuming whatever position is most comfortable for them during this time, except flat on their back (Mirzakhani, 2020).

This phase can be difficult because contractions grow so much stronger and last so much longer than they did in the latent phase that the patient begins to experience true dis- comfort. It is also both an exciting and a frightening time because it is obvious something dramatic is definitely happening. In a few hours, a patient will have a new baby. Their life will never be the same again.

The Transition Phase

During the transition phase, contractions reach their peak of intensity, occurring every 2 to 3 minutes with a duration of 60 to 70 seconds, and a maximum cervical dilatation of 8 to 10 cm occurs. If it has not previously occurred, show will occur as the last of the mucus plug from the cervix is released. If the membranes have not previously ruptured, they will usually rupture at full dilatation (10 cm). By the end of this phase, both full dilatation (10 cm) and complete cervical effacement (obliteration of the cervix) have occurred.

During this phase, a patient may experience intense discomfort that is so strong it might be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. They may also experience a feeling of loss of control, anxiety, panic, and/or irritability. Because of the intensity and duration of the contractions, it may seem as though labor has taken charge of them. A few minutes before, they may have enjoyed having their forehead wiped with a cool cloth or their back rubbed. Now, they may knock a partner's hand away. Their focus turns entirely inward to the task of birthing the baby. As a patient reaches the end of this stage at 10 cm of dilatation, unless they have been administered epidural anesthesia, a new sensation, the irresistible urge to push, usually begins.

THE SECOND STAGE

What If... 15.1

C.B. tells the nurse she is certain her labor is going wrong because it has lasted over 6 hours. Is this an unusually long time for a first stage of labor for a person having their first child? Would she be comforted by learning the usual length?

The second stage of labor is the time span from full dilatation and cervical effacement to birth of the infant. A patient typically feels contractions change from the characteristic crescendo-decrescendo pattern to an uncontrollable urge to push or bear down with each contraction as if to move their bowels. They may experience only momentary nausea or vomiting because pressure is no longer exerted on their stomach as the fetus descends into the pelvis. The patient pushes with such force that they perspire and the blood vessels in their neck become distended.

The fetus begins descent and, as the fetal head touches the internal perineum to begin internal rotation, the perineum begins to bulge and appear tense. The anus may become everted, and stool may be expelled. As the fetal head pushes against the vaginal introitus, this opens and the fetal scalp appears at the opening to the vagina and enlarges from the size of a dime, to a quartet, then a half-dollar. This is termed crowning.

It takes a few contractions of this new type for a patient to realize everything is alright, just different, and to appreciate it feels better and less frightening to push with contractions. As they concentrate on pushing, they may become unaware of the conversation in the room. Pain may disappear as all of their energy and thoughts are directed toward giving birth. As the fetal head is pushed out of the birth canal, it extends and then rotates to bring the shoulders into the best line with the pelvis. The body of the baby is then born.

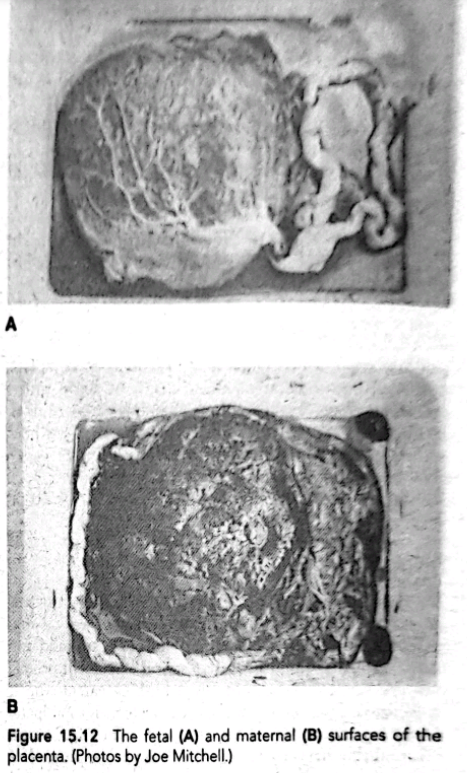

THE THIRD STAGE

The third stage of labor, the placental stage, begins with the birth of the infant and ends with the delivery of the placenta. Two separate phases are involved: placental separation and placental expulsion.

After the birth of the infant, the uterus can be palpated as a firm, round mass just below the level of the umbilicus. After a few minutes of rest, uterine contractions begin again, and the organ assumes a discoid shape. It retains this new shape until the placenta has separated, approximately 5 minutes after the birth of the infant.

Placental Separation

As the uterus contracts down on an almost empty interior, there is such a disproportion between the placenta and the contracting wall of the uterus that folding and separation of the placenta occur. Active bleeding on the maternal sur- face of the placenta begins with separation, which helps to separate the placenta still further by pushing it away from its attachment site. As separation is completed, the placenta sinks to the lower uterine segment or the upper vagina. The placenta has loosened and is ready to deliver when: There is lengthening of the umbilical cord.

A sudden gush of vaginal blood occurs. The placenta is visible at the vaginal opening. The uterus contracts and feels firm again.

If the placenta separates first at its center and lastly at its edges, it tends to fold on itself like an umbrella and presents at the vaginal opening with the fetal surface evident. Ap- proximately 80% of placentas separate and present in this way. Appearing shiny and glistening from the fetal mem- branes, this is called a Schultze presentation. If, however, the placenta separates first at its edges, it slides along the uterine surface and presents at the vagina with the maternal surface evident. It looks raw, red, and irregular, with the ridges or cotyledons that separate blood collection spaces evident; this is called a Duncan presentation. Although there is no difference in the outcome, record which way the placenta presented. A simple trick of remembering the presentations is remembering that if the placenta appears shiny, it is a Schultze presentation. If it looks "dirty" (the irregular maternal surface shows), it is a Duncan presenta- tion (Fig. 15.12).

This stage can take anywhere from 1 to 30 minutes and still be considered normal. Because bleeding occurs as the placenta separates, before the uterus contracts sufficiently to seal maternal capillaries, there is a blood loss of about 300 to 500 mL, not a great amount in relation to the extra blood volume that was formed during pregnancy.

Placental Expulsion

Once separation has occurred, the placenta delivers either by the natural bearing-down effort of the birthing parent or by gentle pressure on the contracted uterine fundus by the primary healthcare provider (a Credé maneuver). Pressure should never be applied to a uterus in a noncontracted state because doing so could cause the uterus to evert (turn inside out), accompanied by massive hemorrhage (Cunningham et al., 2018). If the placenta does not deliver spontaneously, it can be removed manually. It needs to be inspected after delivery to be certain it is intact and part of it was not re- tained (which could prevent the uterus from fully contracting and lead to postpartal hemorrhage). In recognition of cultural preferences, be certain to ask if a patient wants to take home the placenta because this can be a strong cultural tradition you don't want to break (Box 15.3).

Some patients choose to have a cord blood sample with- drawn from the cord to be banked for stem cell transplanta- tion in the future. In some major health centers, patients may be asked to donate a placental blood sample for a community stem cell banking program (Munro et al., 2019).

Nursing Care Planning to Respect Diversity BOX 15.3

It is important for birthing parents to understand what is happening to them during labor so they can make informed decisions as to their care. If a person is not proficient in English, make arrangements to locate an interpreter. If they have a hearing impairment, it is the healthcare facility's responsibility to provide an inter- preter so they can receive adequate explanations of progress. Remember, whether a person enjoys being touched or not is in part culturally influenced. Assess early in labor whether they might benefit from such car- ing measures as having their hand held or their back rubbed or if they want this only from a support person.

For most healthcare providers in the United States, a placenta has little importance or meaning after its work of fetal oxygenation is done. Worldwide, however, the placenta has continuing importance. Based on this, ask patients if they want to take it home with them. In a number of Asian and Native American cultures, it is, important to bury the placenta to ensure the child will continue to be healthy. Be certain when supplying pla- centas to take home that you respect standard infection precautions and hospital policy.

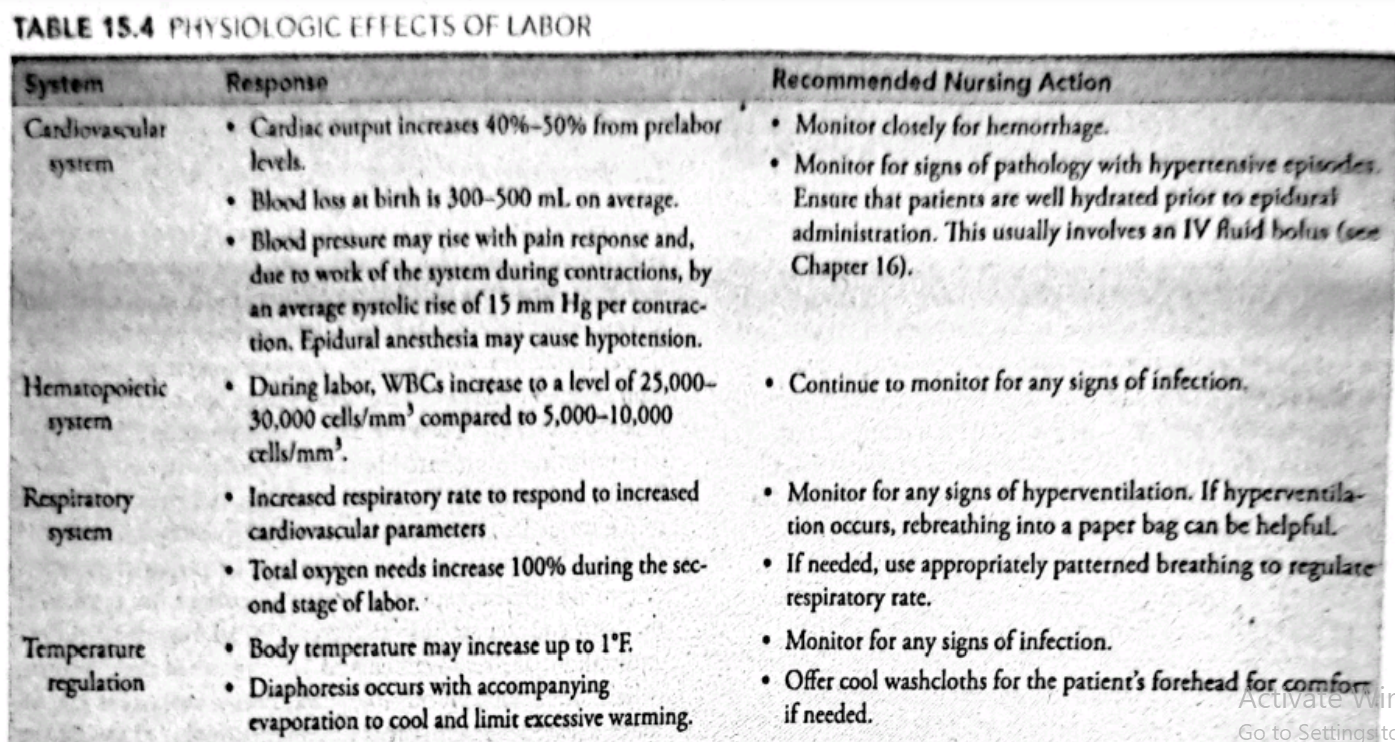

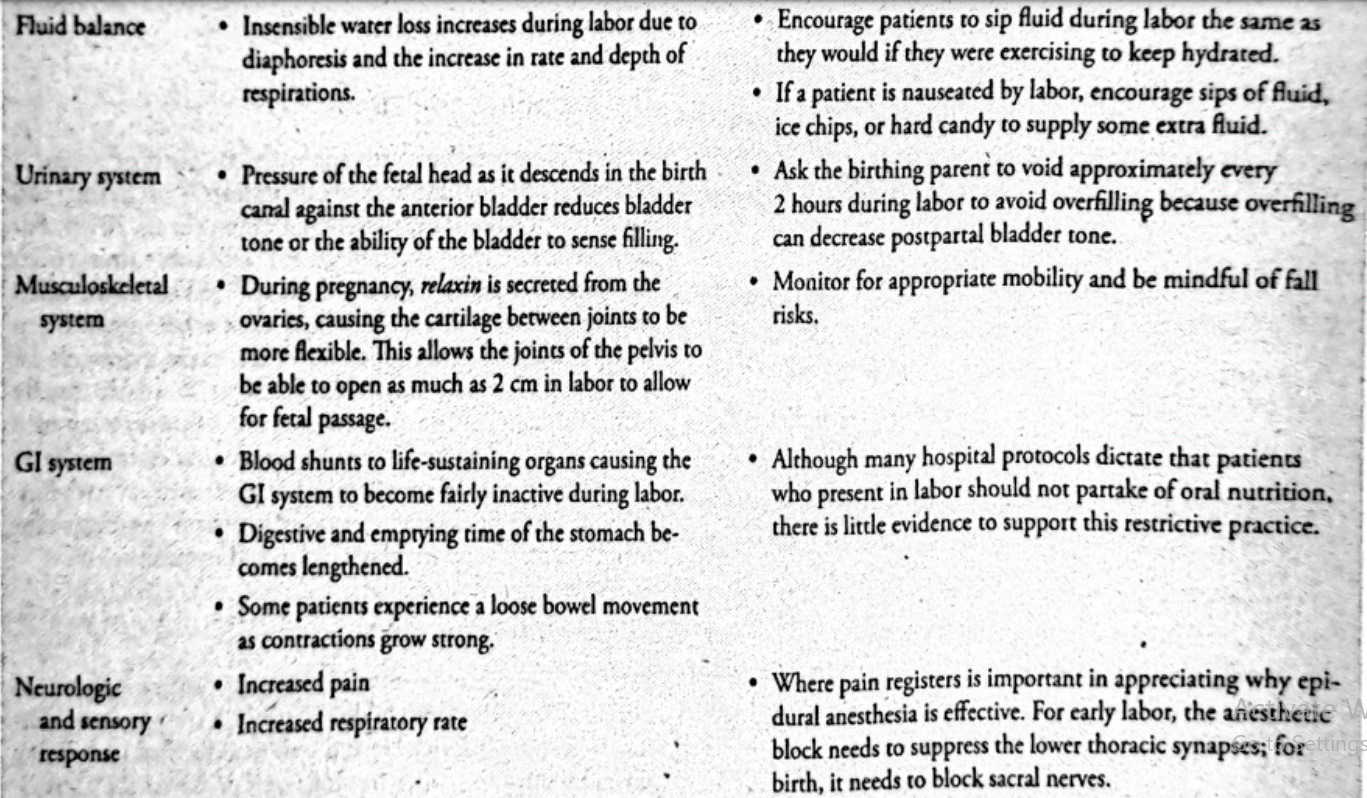

Maternal and Fetal Responses to Labor

Labor is a local process that involves the abdomen and repro- ductive organs, but because it is such an intense process, it has systemic physiologic effects on both a birthing parent and the fetus. Its intensity is so great that almost all body systems are affected by it.

THE MATERNAL PHYSIOLOGIC EFFECTS AND PSYCHOLOGICAL RESPONSES

Pregnancy has effects on many systems of the birthing parent. During labor, there are yet further effects which may require the nurse to deliver specific care to their patient. Knowing and recognizing what is normal and what is not normal can help to ensure safe provision of care (Table 15.4).

The Response to Pain

Cultural factors can strongly influence a patient's experience and satisfaction with labor. In the past, Americans were accus tomed to expecting hospital procedures and a medical model of care and therefore followed instructions with few ques tions. Today, birthing parents are encouraged to help plan their care. In addition, every person responds to cultural cues in some way. This makes the patient's response to pain, choice of nourishment, preferred birthing position, desired proxim- ity and involvement of a support person, and customs related to the immediate postpartal period highly individualized.

To make labor a positive experience, be prepared to adapt care to the patient's specific needs. If a patient has traditions that run counter to hospital protocols, address these differ- ences and make arrangements to accommodate their desires, beliefs, or customs, if possible, such as advocating for special foods to eat, dancing in order to remain upright, or saving the placenta for the patient to take home.

The Response to Fatigue

By the time the date of birth approaches, a birthing parent is generally tired from the normal discomforts of pregnancy and has not slept well for the past month (Young et al., 2018). For example, a side-lying position caused backache, turning onto their back caused the fetus to kick and waken them; when they turned back to the side, their back ached again. Sleep hunger from this type of discomfort can make it difficult for a person to perceive situations clearly or to adjust rapidly to new situations. It can make a small deficiency such as a wrinkled sheet appear as a major threatening discrepancy in care. It can make the process of labor loom as an overwhelm- ing, unendurable experience unless the patient has competent people to offer support, reassurance, and comfort.

The Response to Fear

Patients appreciate a review of the labor process early in la- bor as a reminder that childbirth is not a strange, bewilder- ing event but a predictable and well-documented one. Being taken by surprise-labor moving faster or slower than antici- pated or contractions harder and longer than they remember from a previous pregnancy-can lead a patient to feel out of control and increase their level of pain. This sense of lack of control combined with pain may cause a patient to be- gin to worry for the infant and fear they will not meet their own behavioral expectations. Explain and repeat as necessary that labor is predictable but also variable. Contractions last a certain length and reach a certain intensity but always have a rest period in between, so patients can have a break from pain. Fear of labor this way releases adrenaline, and adrena- line interferes with oxytocin release and so can limit the ef- fectiveness of uterine contractions. Patients with a history of sexual trauma may have an extremely heightened sense of fear during childbirth as the physical sensations and feeling of a lack of control can trigger flashbacks and other PTSD responses during labor (Scoglio et al., 2021). It is important to be mindful of consent during the childbearing process and

FETAL RESPONSES TO LABOR

The pressure and circulatory changes that occur with contrac tions not only affect the birthing parent but also can cause detectable physiologic changes in the fetus as well.

The Neurologic System

Uterine contractions exert pressure on the fetal head, so the same response that is involved with any instance of increased intracranial pressure occurs. The fetal heart rate (FHR) de- creases by as much as five beats per minute during a con- traction, as soon as contraction strength reaches 40 mm Hg; although not measurable, fetal blood pressure also rises. The decrease in FHR appears on a fetal heart monitor as a normal or early deceleration pattern.

The Cardiovascular System

A sufficiently mature fetus is unaffected by the continual vari- ations of heart rate that occur with labor contractions. Dur- ing a contraction, as the arteries of the uterus become sharply constricted, and the filling of cotyledons almost completely halts, the amount of nutrients, including oxygen, exchanged during this time is greatly reduced, causing a slight but in- consequential fetal hypoxia. The increase in blood pressure caused by increased intracranial pressure raises blood pressure and keeps circulation from falling below normal for the dura- tion of a contraction.

The Integumentary System

The pressure involved in the birth process is often reflected in minimal petechiae or ecchymotic areas on a fetus (particu- larly the presenting part). There may also be edema of the presenting part (caput succedaneum) from this pressure.

The Musculoskeletal System

The force of uterine contractions tends to push a fetus into a position of full flexion or with the head bent forward, which is the most advantageous position for birth.

The Respiratory System

The process of labor appears to aid in the maturation of surfactant production by alveoli in the fetal lung. Both the pressure applied to the chest from contractions and passage through the birth canal help to clear the respiratory tract of lung fluid. For this reason, an infant born vaginally is usually able to establish respirations more easily than a fetus born by cesarean birth.

Measuring Progress in Labor

A patient's progress in labor is recorded on a labor record (a Partogram) devised by the World Health Organization, or a like form on which vital signs, FHR, cervical dilatation, descent of the fetal head, urine tests, and any drugs adminis- tered can be recorded.

Remember, when using such forms, how much and what type of analgesia a patient receives in labor should not influ ence the length of labor but may affect how long the second stage (pushing) lasts. Because "norms" on such a record refer to averages, an individual's labor can vary greatly from the ideal projected course of labor and still be normal.

After each cervical examination, cervical dilatation and fe tal descent (which may be referred to as "station") are plotted on the graph. The pattern of cervical dilatation usually plots as a rising S-shaped curve. You may need to remind patients that assessments of cervical dilatation are subjective, so one examiner may report a different finding from another (King et al., 2019).

Labor may take over 6 hours to progress from 4 to 5 cm and over 3 hours to progress from 5 to 6 cm of dilatation. Nulliparas and multiparas progress at a pace that is similar be- fore 6 cm. However, after 6 cm, labor accelerates much faster in multiparas than in nulliparas. The Friedman's curve, which had been used as the standard for labor progression, has more recently been phased out (Cohen & Friedman, 2018).

MATERNAL DANGER SIGNS OF LABOR

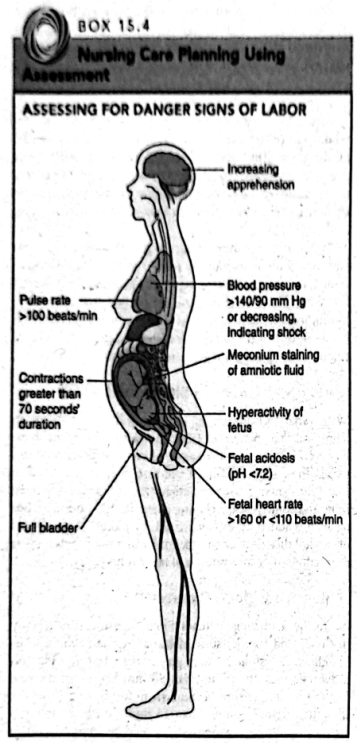

Wide variation exists among individuals in their response to labor and their pattern of labor contractions. Certain signs, however, indicate that the course of events is deviating from usual. These signs, both fetal and maternal, are described in Box 15.4. Nursing care of a patient who is experiencing these signs and so may be developing a complication during labor or birth is addressed in Chapter 23. In addition to problems of cervical dilatation or contractions, other symptoms suggest augmentation or intervention of labor is necessary.

High or Low Blood Pressure

Normally, a birthing parent's blood pressure rises slightly in the second (pelvic) stage of labor because of their push- ing effort. A systolic pressure greater than 140 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm Hg, or an increase in the systolic pressure of more than 30 mm Hg or in the diastolic pressure of more than 15 mm Hg (the basic crite- ria for gestational hypertension), should be reported. Just as important to report is a falling blood pressure because it may be the first sign of intrauterine hemorrhage, although a fall- ing blood pressure from hemorrhage is often associated with other clinical signs of hypovolemic shock, such as apprehen- sion, increased pulse rate, and pallor.

Abnormal Pulse

Most patients during pregnancy have a pulse rate of 70 to 80 beats per minute. This rate normally increases slightly during the second stage of labor because of the exertion involved. A. maternal pulse rate greater than 100 beats per minute during labor is unusual and should be reported because it may be another indication of hemorrhage.

Inadequate or Prolonged Contractions

Uterine contractions normally become more frequent, in- tense, and longer as labor progresses. If they become less fre- quent, less intense, or shorter in duration, this may indicate uterine exhaustion (inertia). This problem may be correctable but needs augmentation or other interventions.

Abnormal Lower Abdominal Contour

If a patient has a full bladder during labor, a round bulge appears on the lower anterior abdomen. This is a danger sig- nal for two reasons: First, the bladder may be injured by the pressure of the fetal head pressing against it; and second, the pressure of the full bladder may not allow the fetal head to descend. To avoid a full bladder, ask patients to try to void about every 2 hours during labor.

Increasing Apprehension

Warnings of psychological danger during labor are as im- portant to consider in assessing maternal well-being as are physical signs. Approaching the second stage of labor, a s tient who is becoming increasingly apprehensive despite dese explanations of unfolding events may not be "hearing be cause they have a concern that has not been met. Using an ap proach such as, "You seem more and more concerned. Could you tell me what is worrying you?" may be helpful. Increasing apprehension also needs to be investigated for physical res sons because it can be a sign of oxygen deprivation or internal hemorrhage,

FETAL DANGER SIGNS OF LABOR

As well as observing for a birthing parent's danger signs of pregnancy, observing fetal danger signs is equally important. These fetal danger signs include the following.

High or Low Fetal Heart Rate

As a rule, an FHR of more than 160 beats per minute (fetal tachycardia) or less than 110 beats per minute (fetal bradycar dia) is a sign of possible fetal distress. An equally important sign is a late or variable deceleration pattern revealed on a fe tal monitor (described later in this chapter). Frequent moni- toring by a fetoscope, Doppler, or a monitor is necessary to detect these changes as they first occur.

Meconium Staining

This is not always a sign of fetal distress, but is highly cor- I related with its occurrence. Meconium staining, a green color in the amniotic fluid, reveals the fetus has had a loss of rectal sphincter control, allowing meconium to pass into the amniotic fluid. It may indicate a fetus has or is experienc- ing hypoxia, which stimulates the vagal reflex and leads to increased bowel motility. Although meconium staining may be usual in a breech presentation because pressure on the but- tocks causes meconium loss, it should always be reported im- mediately even with breech presentations so its cause can be investigated.

Hyperactivity

Ordinarily, a fetus remains quiet and barely moves during la- bor. Fetal hyperactivity may be a subtle sign that hypoxia is occurring because frantic motion is a common reaction to the need for oxygen.

Low Oxygen Saturation

Oxygen saturation in a fetus is normally 40% to 70%. A fe- tus can be assessed for this by a catheter inserted next to the cheek (under 40% oxygenation needs further assessment). If fetal blood is obtained by scalp puncture, the finding of aci- dosis (blood pH lower than 7.2) suggests fetal well-being is becoming compromised and that further investigation is also necessary.

Maternal and Fetal Assessments During Labor

Patients are invariably nervous when they arrive at a hospi- tal or birth center. Nursing assessment is important to detect how they are managing physically and emotionally to this in- tense event in their life.

THE IMMEDIATE ASSESSMENT OF A PATIENT IN FIRST STAGE OF LABOR

A number of immediate assessment measures are necessary to safeguard maternal and fetal health when a patient first arrives at a birthing facility. After the patient and any support person are oriented to the area, focus on obtaining this vital assessment data.

The Initial Interview and Physical Examination

Information about the pregnancy can be gained from the pre- natal record electronically on admission or if a paper copy has been forwarded to the birth setting beforehand. Addi- tional important data that needs to be obtained includes a description of labor thus far, general physical condition, and preparedness and plans for labor and birth. This amount of information is scant but helps to establish whether the pa- tient is in active labor and needs immediate preparation for birth or whether they have arrived at the birthing setting at an early stage of labor and therefore will benefit most from paced interventions. Ask about the following:

Expected date of birth/delivery (EDB or EDD)

When contractions began

Amount and character of any show

Whether rupture of membranes has occurred

Any known drug allergies

Any recreational or prescription drugs used (patients ad- dicted to opioids need special precautions before analge- sia is administered for pain management; their newborn may need special care to prevent neonatal abstinence syndrome from opioid withdrawal)

Past pregnancy and present pregnancy history if the pre- natal record is not available. It is important to note the route of delivery with any prior births as well as any complications which may have occurred.

The birth plan or what individualized measures they think will create a memorable experience such as whether they want analgesia or who they would like to cut the umbilical cord

Assess the following:

Vital signs: temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure (assess between contractions for comfort and accuracy)

Nature of contractions (frequency, duration, and intensity)

Rating of pain on a 10-point scale

What the patient has done to be prepared for labor such as learning breathing exercises

Urine specimen for protein and glucose

Position and presentation of the fetus

It is important to document fetal presentation and posi tion at the beginning of labor because these help predict if the presentation of a body part other than the vertex could be putting a fetus at risk or leading to the possibility that labor will be longer than usual because fetal descent will be less effective, causing ineffective dilatation of the cervix. A different presentation could also lead to early rupture of membranes, increasing the possibility of infection, fetal anoxia from cord prolapse, and meconium staining, all of which can lead to cesarean birth or respiratory distress at birth (Pilliod & Caughey, 2017).

THE DETAILED ASSESSMENT DURING THE FIRST STAGE OF LABOR

If the patient is in active labor, the history taken on arrival may be the only history obtained until after the baby is born. If birth is not imminent, both a more extensive history and a physical examination can be obtained.

The History

Performing a detailed interview of a person in labor can be difficult because of the constant interruptions labor contrac- tions cause. Be patient until a contraction ends so you don't interrupt any form of controlled breathing a patient is us- ing. Remember, the longest contraction is rarely more than 60 seconds. If a patient concentrates so intently on a breath- ing exercise that they completely forget a question asked just before a contraction, repeat the question as the contraction subsides, as if it had not been asked before, or as if it is no trouble to ask it again.

Current Pregnancy History

Important information needed for a complete history includes documentation of gravida and parity status, a description of this pregnancy (e.g., intended or not, place and pattern of prenatal care, adequacy of nutrition, whether any complica- tions such as spotting, falls, hypertension of pregnancy, infec- tion, alcohol or drug ingestion occurred during pregnancy), plans for labor (e.g., Do they want to have the baby naturally? Will they use breathing exercises? Will a support person re- main with the patient continuously?), and plans for child- care (e.g., Will they breastfeed? Have they chosen a primary healthcare provider for the baby? If the baby is male, do they want him circumcised?).

Past Pregnancy History

Document prior pregnancies, abortions, or miscarriages, in- cluding number, dates, types of birth, any complications, and outcomes, including health, sex, and birth weights of previ- ous children.

Past Health History

Document any previous surgeries (abdominal surgical ad- hesions might interfere with fetal passage), heart disease or diabetes (special precautions will be required during labor and birth), anemia (blood loss at birth may be more impor tant than usual), tuberculosis (requiring testing after birth to be certain bealed lung lesions weren't reactivated by birth), kidney disease or hypertension (blood pressure must be mon itored even more carefully than usual), or sexually transmit ted infection such as herpes (the infant may be exposed to the disease by vaginal contact if the disease is active). Determine also whether a patient is at risk for prescription or nonpre- scription drug abuse or HIV exposure.

Family Medical History

Ask if any family member has a condition that could be in- herited such as a cognitive challenge, heart disease, blood dyscrasia, diabetes, kidney disease, allergies, seizures, hear- ing loss, or malignant hyperthermia (a dominantly inherited disorder that causes a dangerous increase in temperature in response to certain anesthetics). If any of these are present, adequate preparation can then be made for a child who might have special needs at birth.

The Physical Examination

After history taking, a patient needs a physical examination, including a pelvic examination, to confirm general health, the presentation and position of the fetus, and the stage of cervi- cal dilatation. In order to have an HIV test, a patient must sign additional informed consent over and above the usual health facility consent.

The physical assessment during labor begins, as does all physical assessments, with overall appearance: Does the pa- tient appear tired? Pale? Ill? Frightened? Are there signs of edema or dehydration? Do they have open lesions anywhere? Be prepared to adapt further examination techniques with regard to stage of labor, frequency of contractions, and labor progression.

Be certain to palpate for enlargement of neck lymph nodes to detect the possibility of a respiratory infection. Inspect the mucous membrane of the mouth and the con- junctiva of the eyes for color to see if paleness suggests ane- mia. Examine teeth for caries or abscesses because an oral infection might account for a postpartal fever. Examine the outer and inner surfaces of the lips carefully to detect herpes lesions (pinpoint vesicles on an erythematous base). Report to the patient's primary care provider if herpetic lesions are present anywhere because, although oral lesions are invariably a type 1 herpes virus (common cold sores), type 2 (genital) herpes virus needs to be identified because this can be lethal to newborns; a patient's obstetric health- care provider may suggest that the patient with oral herpes lesions take isolation precautions such as not kissing the newborn until the lesions crust.

Auscultate the lungs to be certain they are clear of rales. Listen for normal heart sounds and rhythms as well. Many pregnant people at term have a grade 2 to 3 systolic ejec tion murmur because of the extra volume of blood that must cross their heart valves. Document if this is noticeable. Next, inspect and palpate the breasts. Are they free of cysts and lumps? Mark the chart of a patient who has a palpable mass in their breasts for reexamination after labor and birth. This is probably an enlarged milk gland but needs further evalua- tion to be certain it is not something more serious such as a breast malignancy.

Abdominal and Lower Leg Assessment

Assessing a patient's abdomen is important to extimate fe size by fundal height (which should be at the level of the phoid process at term). Palpate and percuss the bladder (over the symphysis pubis) to detect a full bladder. Assess for abdominal scars to reveal previous abdominal or pelvic se gery that could have left adhesions.

Finally, inspect lower extremities for skin turgor to as hydration and also for edema and varicose veins. Parlenes with large varicosities are more prone to thrombophlebi after birth than others. Severe edema suggests hypertension of pregnancy. A blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher can confirm this.

Determining Fetal Position, Presentation, and Lie

Four methods can be used to determine if the fetus is in an optimal position for birth:

Determining the place on the patient's abdomen where fetal heart tones are heard strongest

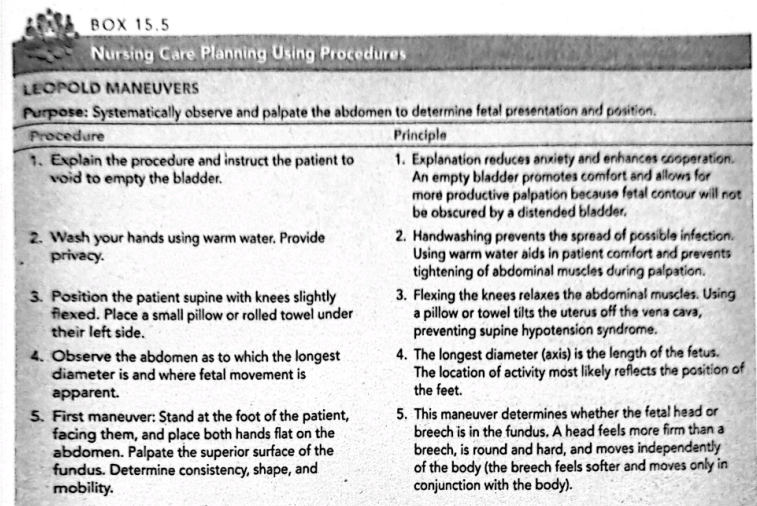

Abdominal inspection and palpation, called Leopold maneuvers

Vaginal examination

Sonography

Leopold Maneuvers

Leopold maneuvers are a systematic method of observation and palpation to determine fetal presentation and position and are done as part of a physical examination. Steps for this are described in Box 15.5.

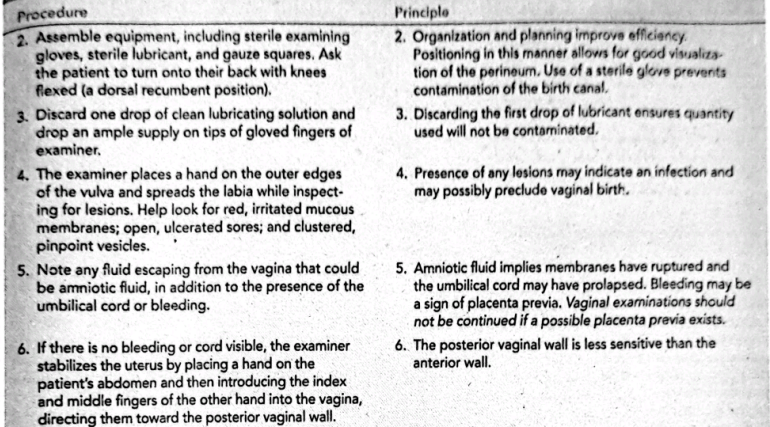

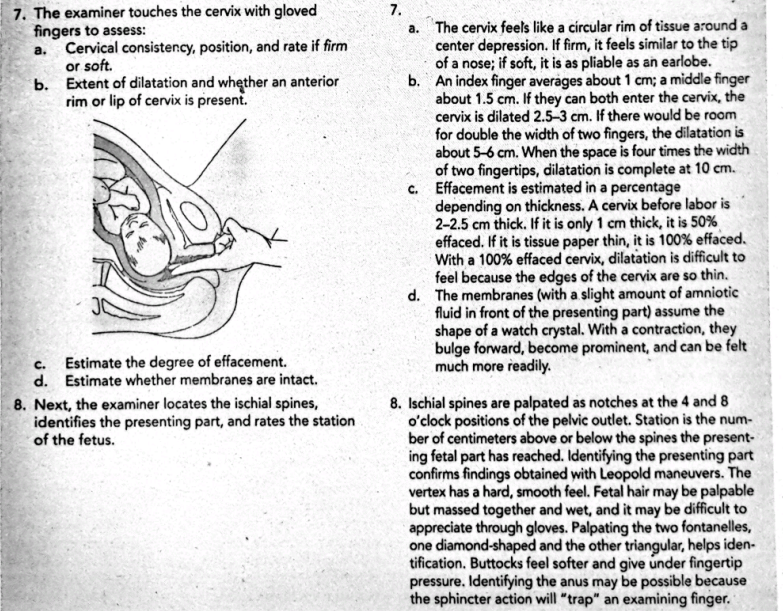

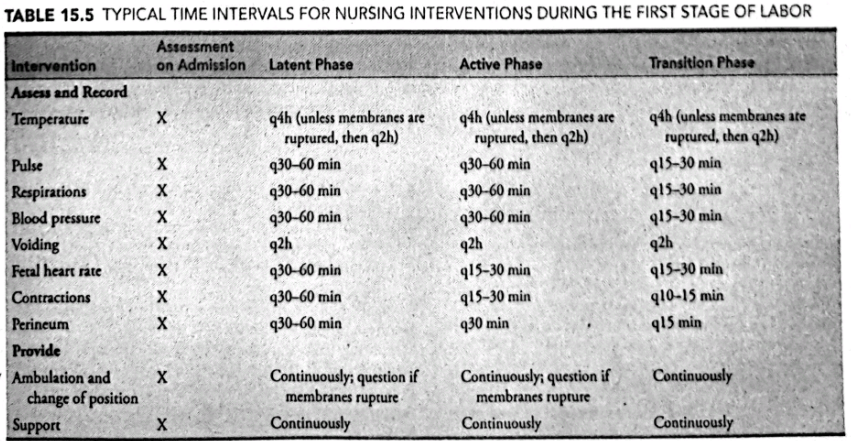

The Vaginal Examination

A vaginal examination is necessary to determine the extent of cervical softening, effacement, and dilatation and to confirm the fetal presentation, position, and degree of descent. These are traditionally done by the primary care provider, but, if not available, they can be done by a nurse skilled in the tech- nique. Responsibilities for helping with a vaginal examina- tion during labor are shown in Box 15.6.

Vaginal examinations are best done between contrac- tions. Although more of the fetal skull can be palpated dur ing a contraction because the cervix retracts more at that time, an examination during a contraction is more uncom- fortable and rarely is justified by the additional amount of information gained. A palpation of membranes during a contraction, when they are under pressure, also can cause them to rupture.

Birthing parents are anxious to have frequent reports dur- ing labor to reassure them that everything is progressing well, but vaginal exams should be kept to a minimum to prevent infection. The primary care provider will tell a patient imme- diately after an examination about labor progress. If giving a progress report, remember that most patients are aware of the word dilatation but not effacement. Just saying, "No further dilatation," therefore can be a depressing report. "You're not dilated a lot more, but a lot of thinning is happening and that's just as important" is the same report given in a positive manner. After a vaginal examination, plot the new degree of dilatation and descent of the presenting part on a labor prog- ress graph, as described earlier.

Vaginal examinations should not be done in the presence of fresh bleeding because fresh bleeding may indicate that a placenta previa (implantation of the placenta so low in the uterus that it is encroaching on the cervical os) is present. Per- forming a vaginal examination in this instance might tear the placenta and cause hemorrhage, resulting in danger to both the pregnant person and fetus. Make certain a primary care provider knows about the fresh bleeding before attempting a vaginal examination.

Patients from cultures where female circumcision is al- lowed may have tightened or obstructed vaginal openings from scarring, which can make a vaginal exam painful. Note this because it also indicates a patient may need a cesarean birth to prevent perineal tearing if their vagina cannot dilate adequately.

Sonography

Although not routine, sonography may be used to determine the diameters of the fetal skull and to determine presenta- tion, position, flexion, and degree of descent of a fetus at the beginning of labor. This is usually done by a portable unit, but if it's necessary for a patient to be transported to another department to have this done, be certain someone accompa- nies them, so, if labor should become more active, they can be returned quickly to the labor or birth service for needed care.

Assessing Rupture of Membranes

One out of every four labors begins with spontaneous rup- ture of the fetal membranes. When this occurs, a birthing parent feels a sudden gush or a slow trickle of amniotic fluid from their vagina. This is a startling sensation for most peo- ple because it feels as if they have lost bladder control. They may feel embarrassed before realizing the warm fluid on their perineum and legs is not urine but an unexpected announce- ment that labor is beginning. If the fluid expelled was only a small amount, there may be a question as to whether the membranes have ruptured.

A sterile vaginal examination using a sterile speculum usually reveals whether amniotic fluid is present in the va- gina. After vaginal secretions are obtained with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator, test them with a strip of Nitrazine paper. Vaginal secretions are usually acid; amniotic fluid, in contrast, is alkaline. If amniotic fluid has passed through the vagina recently, the pH of the vaginal fluid will probably be alkaline (greater than 6.5) when tested by Nitrazine paper (appears blue-green or gray to deep blue). A false blue read- ing may occur in a patient with intact membranes who has a heavy, bloody show because blood is also alkaline. An ad- ditional test that can be done is a fern test (examination of vaginal secretions under a microscope). Because of its high estrogen content, amniotic fluid will show a fern pattern (see Chapter 5, Fig. 5.13A) when dried and examined in this way; urine will not.

If the patient's membranes ruptured at home, ask them to describe the color of the amniotic fluid, the amount, the odor, and the approximate time of rupture. Amniotic fluid should be clear as water. Yellow-stained fluid suggests a blood incompatibility between the birthing parent and fetus (the amniotic fluid is bilirubin stained from the breakdown of red blood cells). Green fluid suggests meconium staining. Although meconium staining is normal in breech births be- cause of compression of the buttocks, in a vertex presenta- tion, it may indicate fetal anoxia. Either way, a fetus with meconium staining needs immediate assessment. After birth, the infant continues to need close assessment at birth to rule out possible meconium aspiration (Kumar et al., 2019). If the fluid is malodorous, there could be an infection. If mem- branes rupture during labor, assess FHR immediately to be certain the umbilical cord hasn't prolapsed and is now being compressed against the cervix by the fetal head. The time of rupture is important because the potential time clock for an infection begins with ruptured membranes. It's preferable if the baby is born within 24 hours of rupture to reduce the risk of infection.

Assessment of Pelvic Adequacy

Evaluating pelvic adequacy using internal conjugate and is- chial tuberosity diameters is generally done during pregnancy either manually or by sonogram; so, by weeks 32 to 36 of pregnancy, a primary care provider can be alerted that cepha- lopelvic disproportion could occur. Because the diameters obtained during pregnancy have not changed, they are not retaken if already obtained.

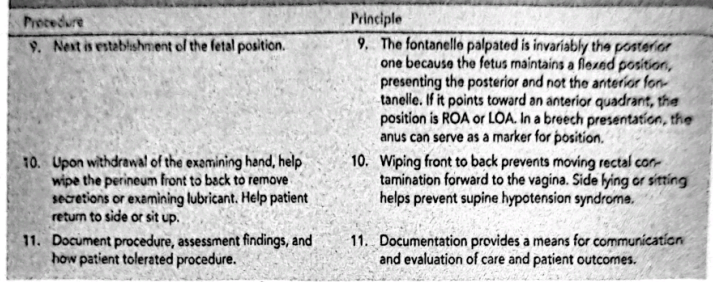

Vital Signs

Vital signs are taken at the beginning and then periodically during labor, as summarized in Table 15.5.

Temperature

Temperature is usually obtained every 4 hours during labor. Report a temperature greater than 99°F (37.2°C) because it may indicate the development of infection. Unless there are accompanying symptoms, however, temperature elevation in a patient who has taken little fluid by mouth usually re- flects dehydration (urge them to drink at least sips of water to maintain hydration). After rupture of the membranes, tem- perature should be taken every 2 hours because the possibility of infection markedly increases after that time.

Pulse and Respiration

The pulse and respiration rate should be measured and re- corded at the same time intervals as temperature. A patient's pulse may be rapid on admission because they are nervous and anxious. After they have become better acquainted with their surroundings and has been assured everything is going well, pulse usually falls in a range between 70 and 80 beats per minute. A persistent pulse rate of more than 100 beats per minute could be tachycardia from dehydration or hem- orrhage and so needs investigation. Respiratory rate during labor is usually 18 to 20 breaths per minute. Do not count respirations during contractions because patients tend to breathe rapidly from pain. Conversely, if a patient is using controlled breathing to decrease pain in labor, their respira- tion rate during contractions can be abnormally slow.

Observe for hyperventilation (rapid, deep respirations) be- cause prolonged hyperventilation can cause a "blowing off" of carbon dioxide and accompanying symptoms of dizziness and tingling of hands and feet. Rebreathing into a paper bag and reassurance the feeling is normal help to reverse this process.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is usually measured and recorded every 4 hours as well. As with pulse and respirations, measure blood pressure between contractions, both for a patient's comfort and for accuracy, because maternal blood pressure tends to rise 5 to 15 mm Hg during a contraction. An increase in blood pressure at other times is potentially dangerous because it may indicate the development of hypertension of preg nancy. A decrease in blood pressure or a decrease in the pulse pressure (the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressures) may indicate hemorrhage. If a patient received an analgesic agent (such as meperidine), which tends to cause hypotension, check the blood pressure approximately 15 minutes after administration to be certain extreme hypo- tension did not occur.

Laboratory Analysis

Most patients have some preliminary laboratory studies done in early labor.

Blood

Blood is drawn for hemoglobin and hematocrit, a serologic test for syphilis (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL] test), hepatitis B antibodies, and blood typing to determine whether a blood incompatibility is likely to exist in the new- born and what type of blood will need to be supplied if the patient should have an acute blood loss. If a patient gives per- mission for HIV testing, blood for this will be drawn as well.

Urine