Chapter 9

Industrialization: The Global Context

In terms of ==energy,== the Industrial Revolution came to rely on fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, ==which supplemented and largely replaced== the earlier energy sources of wind, water, wood, and the muscle power of people and animals that had long sustained humankind.

Europeans learned to exploit guano, or seabird excrement, found on the islands off the coast of Peru. Used as a potent fertilizer, guano enabled highly productive input-intensive farming practices.

Later in the nineteenth century, a so-called second Industrial Revolution focused on

- chemicals

- electricity

- precision machinery

- the telegraph

- telephone

- rubber

- printing

Agriculture too was affected as mechanical reapers, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and ==refrigeration== transformed this most ancient of industries.

The massive extraction of ==nonrenewable== raw materials to feed and to fuel industrial machinery — coal, iron ore, petroleum, and much more — altered the landscape in many places.

Industrial Revolution marked a new era in both human history and the history of the planet that scientists increasingly call the Anthropocene, or the “age of man.”

The First Industrial Society

The British Aristocracy

Individual landowning ==aristocrats, long the dominant class in Britain==, suffered little in material terms from the Industrial Revolution.

For most of the nineteenth century, ==landowners continued to dominate the British Parliament.==

As a class, however, the British aristocracy declined as a result of the Industrial Revolution, as have large landowners in every industrial society. As urban wealth became more important, landed aristocrats had to make way for the up-and-coming businessmen, manufacturers, and bankers, newly enriched by the Industrial Revolution.

The Middle Class

At its upper levels, this middle class contained extremely wealthy factory and mine owners, bankers, and merchants.

Politically they were liberals, favoring constitutional government, private property, free trade, and social reform within limits.

]]Women in such middle-class families were increasingly cast as homemakers, wives, and mothers, charged with creating an emotional haven for their men and a refuge from a heartless and cutthroat capitalist world.]]

The withdrawal of children from productive labor into schools has proved a more enduring phenomenon as industrial economies ==increasingly required a more educated workforce.==

Lower Middle Class included people employed in the growing service sector as clerks, salespeople, bank tellers, hotel staff, secretaries, telephone operators, police officers, and the like.

The Laboring Classes

%%They were manual workers in the mines, ports, factories, construction sites, workshops, and farms of an industrializing Britain.%%

[[These cities were vastly overcrowded and smoky, with wholly insufficient sanitation, periodic epidemics, endless row houses and warehouses, few public services or open spaces, and inadequate and often-polluted water supplies.[[

%%Long%% %%hours, low wages, and child labor were nothing new for the poor, but the routine and monotony of work, dictated by the factory whistle and the needs of machines, imposed novel and highly unwelcome conditions of labor.%%

Britain’s industrialists favored girls and young unmarried women as employees in the textile mills, for they were often willing to accept lower wages, while male owners believed them to be both docile and more suitable for repetitive tasks such as tending machines.

A gendered hierarchy of labor emerged in these factories, with men in supervisory and more skilled positions, while women occupied the less skilled and “lighter” jobs that offered little opportunity for advancement.

A man who could not support his wife was widely considered a failure.

Social Protest

With dues contributed by members, these working-class self-help groups %%provided insurance against sickness, a decent funeral, and an opportunity for social life in an otherwise-bleak environment.%%

Socialist ideas of various kinds gradually spread within the working class, %%challenging the assumptions of a capitalist society.%% Robert Owen (1771–1858), a wealthy British cotton textile manufacturer, urged the creation of small industrial communities where workers and their families would be well treated. He established one such community, with a ten-hour workday, spacious housing, decent wages, and education for children, at his mill in New Lanark in Scotland.

Karl Marx (1818–1883). German by birth, Marx spent much of his life in England, where he witnessed the brutal conditions of CAUSE: Britain’s Industrial Revolution and wrote voluminously about history and economics. EFFECT: His probing analysis led him to conclude that industrial capitalism was an inherently unstable system, doomed to collapse in a revolutionary upheaval that would give birth to a classless socialist society, thus ending forever the ancient conflict between rich and poor.

[[When a working-class political party, the %%Labour Party %%, was established in the 1890s, it advocated a %%reformist program%% and a peaceful democratic transition to socialism, largely rejecting the class struggle and revolutionary %%emphasis of classical Marxism.%%[[

Occurrences that disestablished Marx’s ideas:

Improving material conditions during the second half of the nineteenth century helped move the working-class movement in Britain, Germany, and elsewhere away from a revolutionary posture. Marx had expected industrial capitalist societies to polarize into a small wealthy class and a huge and increasingly impoverished proletariat. However, standing between “the captains of industry” and the workers was a sizable middle and lower middle class, constituting perhaps 30 percent of the population, most of whom were not really wealthy but were immensely proud that they were not manual laborers. Marx had not foreseen the development of this intermediate social group, nor had he imagined that workers could better their standard of living within a capitalist framework. But they did.

- [[%%Wages rose under pressure from unions%%[[

- [[%%cheap imported food improved working-class diets%%[[

- [[%%infant mortality rates fell%%[[

- [[%%shops and chain stores catering to working-class families multiplied%%[[

- [[%%English male workers gradually obtained the right to vote%%[[

- [[%%politicians had an incentive to legislate in their favor,%%[[

- [[%%abolishing child labor%%[[

- [[%%regulating factory conditions%%[[

- [[%%in 1911, inaugurating a system of relief for the unemployed.%%[[

- [[%%Sanitary reform considerably cleaned up the “filth and stink” of early nineteenth-century cities, and urban parks made a modest appearance%%[[

Nationalism, which bound workers in particular countries to their middle-class employers and compatriots, offsetting to some extent the economic and social antagonism between them.

National loyalty had trumped class loyalty.

Europeans in Motion

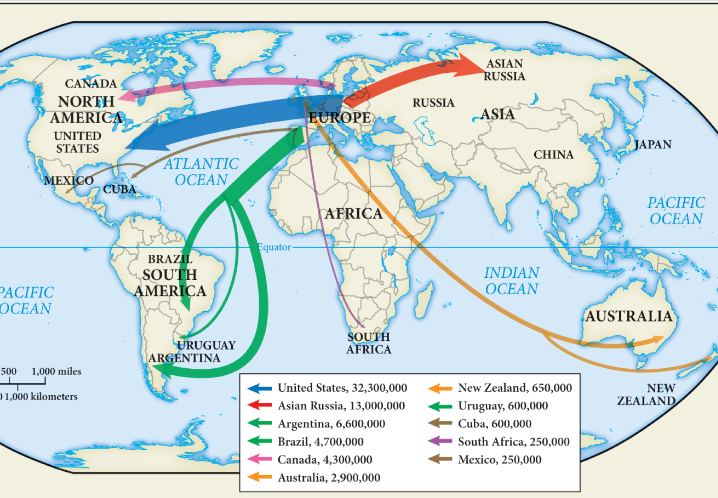

Latin America received about 20 percent of the European migratory stream, mostly from Italy, Spain, and Portugal, with Argentina and Brazil accounting for some 80 percent of those immigrants. Considered “white,” they enhanced the %%social weight%% of the European element in those countries and thus enjoyed economic advantages over the mixed-race, Indian, and African populations.

[[In several ways the immigrant experience in the United States was distinctive. It was far larger and more diverse than elsewhere, with some 32 million newcomers arriving from all over Europe between 1820 and 1930[[

After the freeing of the serfs in 1861, some 13 million Russians and Ukrainians migrated to Siberia, where they overwhelmed the native population of the region, while millions more settled in Central Asia. The availability of land, the prospect of greater freedom from tsarist restrictions and from the exploitation of aristocratic landowners, and the construction of the trans-Siberian railroad — all of this facilitated the continued Europeanization of Siberia.

As in the United States, the Russian government encouraged and aided this process, hoping to forestall Chinese pressures in the region and relieve growing population pressures in the more densely settled western lands of the empire.

Variations on a Theme: Industrialization in the United States and Russia

Similarities:

- New technologies and sources of energy generated vast increases in production and spawned an unprecedented urbanization as well.

- %%Class structures changed as aristocrats, artisans, and peasants declined as classes, while the middle classes and a factory working class grew in numbers and social prominence.%%

- Middle-class women generally %%withdrew from paid labor altogether%%, and their working-class counterparts sought to do so after marriage.

- Working women usually received lower wages than their male counterparts, %%had difficulty joining unions%%, and were accused of taking jobs from men.

- Working-class frustration and anger gave rise to trade unions and socialist movements, injecting a new element of social conflict into industrial societies.

[[Differences:[[

[[French industrialization, for example, occurred more slowly and perhaps less disruptively than did that of Britain.[[

[[Germany focused initially on heavy industry — iron, steel, and coal — rather than on the textile industry with which Britain had begun.[[

[[German industrialization was far more highly concentrated in huge companies called cartels, and it generated a rather more militant and Marxist-oriented labor movement than in Britain.[[

[[Russia, with its Eastern Orthodox Christianity, an autocratic tsar, a huge population of serfs, and an empire stretching across all of northern Asia.[[

[[United States, a young, vigorous, democratic, expanding country, populated largely by people of European descent, along with a substantial number of slaves of African origin.[[

The United States: Industrialization without Socialism

American industrialization began in the textile factories of New England during the 1820s but grew explosively in the half century following the Civil War (1861–1865)

Reasons for its growth:

- The country’s huge size, the ready availability of natural resources, its expanding domestic market, and its relative political stability combined to make the United States the world’s leading industrial power by 1914.

- But unlike Latin America, which also received much foreign investment, the United States was able to use those funds to generate an independent Industrial Revolution of its own.

Tax breaks, huge grants of public land to the railroad companies, laws enabling the easy formation of corporations, and the absence of much overt regulation of industry all fostered the rise of very large business enterprises.

The United States also pioneered techniques of mass production, using interchangeable parts, the assembly line, and “scientific management” to produce for a mass market.

As elsewhere, such conditions generated much labor protest, the formation of unions, strikes, and sometimes violence.

No major political party emerged in the United States to represent the interests of the working class.

Nor did the ideas of socialism, especially those of Marxism, appeal to American workers nearly as much as they did to European laborers.

Why was there a weakness of socialism in the United States?

- One answer lies in the relative conservatism of major American union organizations, especially the ==American Federation of Labor.==

- Massive immigration from Europe, beginning in the 1840s, created a very diverse industrial labor force on top of the country’s sharp racial divide.

- Moreover, the country’s remarkable economic growth generated on average a ==higher standard of living== for American workers than their European counterparts experienced.

- ==Land was cheaper, and home ownership was more available.==

Progressives, who pushed for specific reforms, such as wages-and-hours legislation, better sanitation standards, antitrust laws, and greater governmental intervention in the economy.

Socialism, however, came to be defined as fundamentally “un-American” in a country that so valued individualism and so feared “big government.” It was a distinctive feature of the American response to industrialization.

In the United States, such change bubbled up from society as free farmers, workers, and businessmen sought new opportunities and operated in a political system that gave them varying degrees of expression.

Russia: Industrialization and Revolution:

Russia remained the sole outpost of absolute monarchy, in which the state exercised far greater control over individuals and society than anywhere in the Western world.

Russia still had no national parliament, no legal political parties, and no nationwide elections.

Its upper levels included great landowners, who furnished the state with military officers and leading government officials. Until 1861, most Russians were peasant serfs, bound to the estates of their masters, subject to sales, greatly exploited, and largely at the mercy of their owners. A vast cultural gulf separated these two classes.

In autocratic Russia, change was far more often initiated by the state itself, in its continuing efforts to catch up with the more powerful and innovative states of Europe.

By the 1890s, Russia’s Industrial Revolution was launched and growing rapidly. It focused particularly on railroads and heavy industry and was fueled by a substantial amount of foreign investment.

Until 1897, a thirteen-hour working day was common, while ruthless discipline and overt disrespect from supervisors created resentment. In the absence of legal unions or political parties, these grievances often erupted in the form of large-scale strikes.

In these conditions, a small but growing number of educated Russians found in Marxist socialism a way of understanding the changes they witnessed daily as well as hope for the future in a revolutionary upheaval of workers.

In 1898, they created an illegal Russian Social Democratic Labor Party and quickly became involved in workers’ education, union organizing, and, eventually, revolutionary action.

The Russian Revolution of 1905, though brutally suppressed, forced the tsar’s regime to make more substantial reforms than it had ever contemplated. It granted a constitution, legalized both trade unions and political parties, and permitted the election of a ==national assembly, called the Duma.==

Thus the tsar’s limited political reforms, which had been granted with great reluctance and were often reversed in practice, failed to tame working-class radicalism or to bring social stability to Russia.

Various revolutionary groups, many of them socialist, published pamphlets and newspapers, organized trade unions, and spread their messages among workers and peasants.

After Independence in Latin America

Decimated populations, diminished herds of livestock, flooded or closed silver mines, abandoned farms, shrinking international trade and investment capital, and empty national treasuries — these were the conditions that greeted Latin Americans upon independence.

Conservatives favored centralized authority and sought to maintain the social status quo of the colonial era in alliance with the Catholic Church, which at independence owned perhaps half of all productive land.

Their often-bitter opponents were liberals, who attacked the Church in the name of Enlightenment values, sought at least modest social reforms, and preferred federalism.

In many countries, conflicts between these factions, often violent, enabled military strongmen known as caudillos (kaw-DEE-yos) to achieve power as defenders of order and property, although they too succeeded one another with great frequency.

As in Europe and North America, women remained disenfranchised and wholly outside of formal political life.

Slavery was abolished in most of Latin America by midcentury, although it persisted in both Brazil and Cuba until the late 1880s.

The military provided an avenue of mobility for a few skilled and ambitious mestizo men, some of whom subsequently became caudillos.

Other mixed-race men and women found a place in a small middle class as teachers, shopkeepers, or artisans.

The vast majority — blacks, Indians, and many mixed-race people of both sexes — remained impoverished, working small subsistence farms or laboring in the mines or on the haciendas (ah-see-EHN-duhz) (plantations) of the well-to-do.

One such case was the Caste War of Yucatán (1847–1901), a prolonged struggle of the Maya people of Mexico aimed at cleansing their land of European and mestizo intruders.

Facing the World Economy

During the second half of the nineteenth century, a measure of political consolidation took hold in Latin America, and countries such as Mexico, Peru, and Argentina entered periods of greater stability. At the same time, Latin America as a whole became more closely integrated into a world economy driven by the industrialization of Western Europe and North America.

The new technology of the steamship cut the sailing time between Britain and Argentina almost in half, while the underwater telegraph instantly brought the latest news and fashions of Europe to Latin America.

Latin American export boom increased the value of goods sold abroad by a factor of ten.

Mexico continued to produce large amounts of silver, providing more than half the world’s new supply until 1860.

Becoming like Europe?

The population was also burgeoning; it increased from about 30 million in 1850 to more than 77 million in 1912 as public health measures (such as safe drinking water, inoculations, sewers, and campaigns to eliminate mosquitoes that carried yellow fever) brought down death rates.

There the educated elite, just like the English, drank tea in the afternoon, while discussing European literature, philosophy, and fashion, usually in French.

To become more like Europe, Latin America sought to attract more Europeans. Because civilization, progress, and modernity apparently derived from Europe, many Latin American countries actively sought to increase their “white” populations by deliberately recruiting impoverished Europeans with the promise, mostly unfulfilled, of a new and prosperous life in the New World.

Although local protests and violence were frequent, only in Mexico did these vast inequalities erupt into a nationwide revolution. ==There, in the early twentieth century, middle-class reformers joined with workers and peasants to overthrow the long dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz (r. 1876–1911).== What followed was a decade of bloody conflict (1910–1920) that cost Mexico some 1 million lives, or roughly 10 percent of the population. Huge peasant armies under ==charismatic leaders such as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata helped oust Díaz==.

Mexican Revolution transformed the country. When the dust settled, Mexico had a new constitution (1917) that proclaimed universal male suffrage; provided for the redistribution of land; stripped the Catholic Church of any role in public education and forbade it to own land; announced unheard-of rights for workers, such as a minimum wage and an eight-hour workday; and placed restrictions on foreign ownership of property.

Women were active participants in the Mexican Revolution. They prepared food, nursed the wounded, washed clothes, and at times served as soldiers on the battlefield, as illustrated in this cover image from a French magazine in 1913.

Nowhere in Latin America did it jump-start a thorough Industrial Revolution, despite a few factories that processed foods or manufactured textiles, clothing, and building materials.

Why?

- A social structure that relegated some 90 percent of its population to an impoverished lower class generated only a very small market for manufactured goods

- economically powerful groups such as landowners and cattlemen benefited greatly from exporting agricultural products and had little incentive to invest in manufacturing.

- Domestic manufacturing enterprises could only have competed with cheaper and higher-quality foreign goods if they had been protected for a time by high tariffs.

Instead of their own Industrial Revolutions, Latin Americans developed a form of economic growth that was largely financed by capital from abroad and dependent on European and North American prosperity and decisions.

Later critics saw this dependent development as a new form of colonialism, expressed in the power exercised by foreign investors.

The influence of the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company in Central America was a case in point. Allied with large landowners and compliant politicians, the company pressured the governments of these “banana republics” to maintain conditions favorable to U.S. business.

SAQ References:

- The Sewer King Video