W5: Economic development and the development of competitive advantage

Competition and Market Regulation

the competition and market regulation module uses relevant models of imperfect competition to consider the strategic behaviour of firms in a range of different market setups.

it examines the role of market regulation to ensure that competition is not restricted or undermined in ways that are detrimental to the economy and society

the module introduces various theoretical tools for the analysis of the structure, conduct and performance (SCP paradigm) of markets.

the module uses competition policy to evaluate alternative regulatory interventions for markets.

Industrial Organisation

IO takes a strategic view of how firms interact in imperfectly competitive markets.

Structure-Conduct - Performance vs. New Industrial Organisation

What is an Industrial Organisation

study of how firms behave in markets focusing on imperfect competition

whole range of business issues:

price of a dozen roses

which new products to introduce in mobile industry

merger and acquisition decisions

methods for attacking or defending markets

IO takes a strategic view on how firms interact

How IO proceeds in practice

rely on the tools of game theory

focuses on strategy and interaction

construct models: abstractions

well established tradition in all science simplification but gain the power of generalisaiton

empirical analysis - use theory to form testable hypotheses

measure scale economies for entry deterring actions

experiment with penalty for price-fixing

examine the impact of advertising

Why Industrial Organisation

long standing concern with market power

need for anti-trust policy recognised by Adam Smith

“The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly understocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price.”

“People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment or diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.” (Wealth of Nations, 1776)

Sherman Act (1890)

section 1: prohibits contracts, combinations and conspiracies “in restraint of trade”

section 2: makes illegal any attempt to monopolise a market

Clayton Act (1914)

intended to prevent monopoly “in its incipiency”

makes illegal practices that “may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly”

Federal Trade Commission (1914)

endowed with powers of investigation/adjudication to handle Clayton Act violations

However, application affected by rule of reason

proof of intent/the law does not make mere size an offence

the US Steel case of 2002: the firm had grown to control over 70% of market via merger, but the court found no violation of antitrust

SCP Paradigm vs. New Industrial Organisation

SCP establishes a unidrectional linkage running from market structures → conduct (pricing, advertising etc) → performance of market (economic efficiency/profitability/growth)

NIO emphasises on the feedback effect (bi-directional linkages) running from performances back to conduct; from conduct to structure; and from performance to structure (Phillips, 1976; Clarke, 1985)

New Industrial Organisation

The SCP paradigm has been criticised for overemphasising static models of short run equilibrium (Sawyer, 1985)

theories that focus primarily on strategy and conduct are subsumed under the general heading of the new industrial organisation (NIO) (Schmalensee, 1982)

NIO is an alternative to the SCP paradigm - it can be seen as a natural evolution

increasing emphasis on:

game theory as a means to represent strategic interactions

advanced data analysis and econometric techniques to understand and predict how markets evolve

emphasis on empirical analysis of specific sectors

according to NIO approach, firms are not seen as passive entities, similar in every respect except size. Instead, they are active decision makers, capable of implementing a wide range of diverse strategies.

business strategy:

tactical decisions (today’s price and output to maximise short term profits) versus strategies decisions shaping tomorrow’s market environments

Competition Policy

competition policy is primarily aimed at correcting various types of market failure, increasing competition and giving consumers a wider choice of products and services.

Competition policy rests largely on the theoretical arguments for and against perfect competiton and monopoly.

independence debate:

should authorities be independent of political power? To whom should they be accountable?

how does it affect their own incentives and strategic behaviour?

how long should patent last? Should patent protection be removed altogether (e.g. Covid Vaccine)should authority act in the interest of consumers only, or should they maximise “total” welfare?

Competition policies aimed at increasing competition by discouraging restrictive practices or disallowing mergers on grounds of public interest tend to reduce concentration, or at least prevent concentration from increasing.

tools and mechanisms of competition policy:

antitrust laws: Prohibit anticompetitive behaviours, such as monopolisation, price-fixing, and collusion, which harm competition and consumers

merger control: competition authorities assess mergers and acquisitions to prevent the creation of dominant market players that you stifle competition

Cartel Enforcement: cartels are groups of businesses that collude to fix prices or limit production, undermining competition. Competition policy agencies actively investigate and prosecute cartel activities, imposing fines and penalties on those found guilty

Market investigation: competition authorities may conduct market investigations to identify barriers to competition and propose remedies.

State Aid Control: In the European Union, state aid control ensures that government subsidies do not distort competition in the internal market.

Consumer Protection: beyond competition enforcement, competition policy often includes consumer protection measures to address deceptive advertising, unfair business practices and product safety.

Objectives of Competition Policy

promoting efficiency: Competition encourages firms to operate efficiently and allocate resources effectively. In competitive markets, businesses are motivated to minimise waste, innovate, and constantly improve their processes, leading to increased productivity and economic growth

protecting consumers: one of the primary goals of competition policy is to safeguard the interest of consumers. By preventing anticompetitive practices, such as price-fixing and collusion, consumers benefit from lower prices, greater choice, and higher quality products and services.

encouraging innovation: competition stimulates innovation by pushing firms to develop new technologies, products, and services to gain a competitive edge. This benefits businesses and society through technological advancements

ensuring fairness: competition policy aims to create a level playing field where all market participants have an equal opportunity to succeed. This fairness enhances economic inclusivity and reduces barriers to entry for new and smaller businesses.

Importance of competition policy

competition policy plays a pivotal role in ensuring fair and efficient market structures, thereby promoting economic growth and consumer welfare

it encompasses a set of rules and regulations aimed at preventing anticompetitive behaviour, fostering a level playing field for firms, and safeguarding the interests of consumers

it encourages innovation, efficiency, and economic dynamism. When markets are competitive, firms are incentivised to continually improve their products and services, reduce costs, and seek innovative solutions

consumers benefit from a wider choice of goods and services, lower prices and better quality

in this context, competition policy acts as a guardian of fair competition, preventing monopolies, cartels and other anticompetitive practices that can harm both consumers and smaller businesses

Market regulation

concerns regarding the inefficiency associated with the exercise of market power typically result in regulation

debate on whether to strive to foster competition versus imposing strict regulatory requirements

behavioural economics insights increasingly relevant in the debate, in particular with regards to understanding/predicting consumers’ behaviour and consequent incentives to complete

antitrust laws are supposed to limit the acquisition, protection, and extension of market power

natural monopolies: cases where it is more efficient to have one single provider (e.g. utilities, but not as often as in the past)

in these cases, authorities/governments impose restrictions on firms’ behaviour, e.g. setting price caps

Conclusion

competition and market regulation are vital elements of modern economies, contributing to economic growth, consumer welfare and innovation

by preventing anticompetitive behaviour and ensuring a level playing field for businesses, this fosters an environment where firms are incentivised to innovate and compete favourably, leading to better products, lower prices, and increased economic dynamism

as markets evolve and globalise, competition policy and market regulation will continue to adapt and play a pivotal role in shaping fair and efficient market structures for the benefit of it all.

to maximise the impact, competition authorities should strike a delicate balance between promoting competition and allowing for market flexibility, all while protecting the interests of the society and fostering economic growth and prosperity.

The rise of Keynesianism and the Managed Economy

We saw previously in what is described as the Brenner Debate a discussion around the historical origins of British capitalism in and around the 17th century. This debate revolved around the extent to which technology, trade, class conflict or social relations played the most significant role in the origins of market economies based upon free wage labour.

A similar debate emerges in the 1940s and again in the 1970s around the post war settlement and the rise of Keynesian macroeconomic ideas of the managed economy, and then subsequently in the 1970s with the rise of monetarism and microeconomic supply-side economics.

On these occasions we see a focus upon trade and regulation of the market economy, technology and relative economic decline and finally the emergence of the cold war and social relations of labour control.

We have previously looked at the rise of the post war institutions, governing the rise of post second world war trade and the development of the long-boom, known as the Golden Age. This was rooted within the development of Keynesian macroeconomic policy and what is termed market failures of unmanaged markets.

We look at these debates in the immediate post war period and then in the following lectures re-examine these debates in response to the crisis of Keynesianism and the rise of Monetarism from the 1970s.

The Keynesian Revolution

John Maynard Keynes developed different views on how economies operated, ushering in what is referred to as a Keynesian Revolution. His General Theory published in 1936 placed the problem of the interwar depression with a herd mentality restricting investment, growth and development.

Entrepreneurs in periods of optimism would invest in new technologies and productive capacity but in periods of crisis would refrain from investment due to uncertainty of the outcomes of investment. This ‘animal spirit’ and herd mentality would reinforce economic downturns, raise unemployment and cut consumption. Which itself would lead to a reduction of demand and further cuts in supply as firms reduced output.

“Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits - a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.” (Keynes, General Theory - 1936, pp. 161-162)

For Keynes government action was necessary to prevent such an outcome. Most notably because government expenditure was not like normal household consumption. While individuals would use up value in their consumption of goods and services, when government use up value it creates new opportunities for value to be created. Government Investment in goods and services - roads, infrastructure or health and education meant that Government expenditure had a multiplier effect unlike household consumption.

Joseph Schumpeter and “Winds of Creative Destruction”

From a different perspective the neo-classical economist Joseph Schumpeter was much more pessimistic about the extent to which capitalist development could continue. Writing in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, published in 1943 he saw the rise of big business and autarky demolishing capitalist development and stifling economic activity.

“The opening up of new markets… incessantly revolutionises the economic structures from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.” Schumpeter (1943), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p 83

But for Schumpeter this creative destruction was itself being undermined and destroyed by the monopolistic development of the firm and the replacement of the market by the large firm in the USA, by state-led private firms in Nazi Germany and nationalised industries in the Soviet Union was leading to the wiping out of democracy and the ending of capitalism.

“The bureaucratic method of transacting business and the moral atmosphere it spreads doubtless often exert a depressing influence on the most active minds, Mainly this is due to the difficulty, inherent in the bureaucratic machine, of reconciling individual initiative with the mechanics of its working. Often the machine gives little hope for initiative and much scope for vicious attempts at smothering it.” Schumpeter (1943), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, p. 207

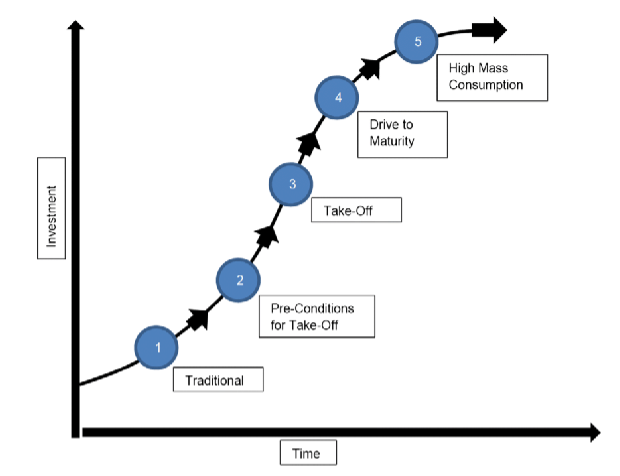

Rostow 5 stages of Economic Growth

An alternative to the pessimism of Schumpeter and an alternative to the Keynesian module of state-led economic development came from the work of neo-classical school of development economics W.W. Rostow. His book The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto first published in 1960 rejected demand management and instead focused upon the development of what he termed the 5 stages of growth.

Traditional societies - the emergence of agricultural societies, based around villages and labour linked to formal structures of clans, feudalism.

Pre-conditions for take off - the movement of labour away from agriculture into towns with free-labour, new forms of religious ideas emphasising the ‘work ethic’ and industriousness.

Take-off - the first industrial revolution, emergence of the factory system, national markets and nation states.

The drive to maturity - economic development beyond the industries of the first industrial revolution and growth of output and expansion of international trade and development of welfare systems.

The age of mass consumption - emergence of globalisation rules-based systems of governance, the maturity of welfare states, mass tertiary education and movement towards higher technology and service sectors.

These differing approaches are themselves responding to the need to create a stable system of economic development, in contrast to that of the interwar years and the rise of an alternative economic system which has emerged in the Russian revolution of 1917.

The creation of a cold war between the ‘first world’ of Western Europe and north America in contrast to the ‘second world’ of Stalinist Russia and the eastern European states which contribute to the USSR, along with China under Maoism is understood as a threat to market capitalism.

For Trotsky this gave rise to an understanding of the internationalisation of the Russian revolution in 1917, so feared by European and American governments.

“It is nonsense to say that historical stages cannot in general be skipped. The long historical process always makes leaps and isolated stages which derive from the theoretical breakdown into its component parts of the process of development in its entirety… in Russia… the factory came by skipping over the epoch of manufacture and urban handicrafts.” - Trotsky (1930), The Permanent Revolution: Results and Prospects (1906) p.116

The defeat of Trotsky by Stalin and the rise of Stalinism by the 1930s led to an alternative development than that identified by combined and uneven development, namely the catching up with the west. Enforced industrialisation.

As Stalin put it in 1931 with the introduction of the first Five Year Plan:

“We are 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this lag in ten years. Either we do it, or they crush us!” - Josef Stalin, speech to the Fourth Plenum of Industrial Managers, 1931

Conclusion

The mid-twentieth century saw the development of a series of conflicting economic approaches to economic growth. Underpinning these economic debates were political and social changes that had arisen in response to the collapse of the laissez faire market economy of pre-world war one and the depression of the 1920s and 1930s.

At the heart of these debates lay discussions about the extent to which the state and its bodies in government was necessary in the economic development of industry. In all cases governments from the 1950s onwards was understood, to have a greater or lesser extent, a significant role in economic development.

It was not until the 1970s that this consensus began to break-down and new ideas emerged which returned to the centrality of markets over the role of the state.

Path Dependency and Relative Economic Decline

The crisis of the 1970s globally led to a re-evaluation and rejection of Keynesian demand management. Now instead of a multiplier effect from government expenditure a new thesis of ‘crowding out’ gained popularity. Private investment would flow to areas for profitable investment if private investors weren’t crowded out by government borrowing sucking up all available access to financial capital.

This combined with a new approach to monetary policy originating from Hayek in the 1950s and Milton Friedman in the 1970s gained credence. Inflation was a product of too much money being supplied to the economy. The quantity theory of money argued that restricting the money supply would lead to a control over inflation and a stability of prices.

Now the state’s role was to create and police the rules of the game, reinforce private property rights and remove itself from economic activity in the market. Monetarism and supply-side economic policy was to triumph by the end of the 1970s and be the claimed government policy through the 1980s.

Again this debate took place over the explanation for the crisis which occurred throughout the world but was particularly acute in Britain.

The relative economic decline of the British economy, relative to other developing and advanced economies, became a focus for this debate. Again, it developed in terms of failures of institutions and government, failures of the market and firms to invest in newer technologies and competitive industries or failures of labour and its demands for higher wages to keep up with failures.

The Impact of the Crisis in Britain

The long boom was already faltering by 1973 when OPEC increased the price of oil by over 300% from $3.45 to $11.58. The first oil price rise was not the only cause of changes in the 1970s but it had an immediate and marked impact on oil dependent economies such as Britain.

A sharp deterioration of the balance of payments occurred due to increased costs of imports. This trade deficit had a resulting deflationary effect on the British economy and other oil importing economies. As a result exports to advanced economies also fell further impacting on balance of payments.

The oil price increase also fuelled inflationary pressures as raw material costs increased with the result that the decade was characterised as one in which stagnation and inflation occurred - or stagflation.

The decade of the 1970s can be broadly defined into three sub-periods:

1970-4 the period of the heath government

1974-6 the last years of Wilson as leader of the Labour Party and the first half of the Labour government

1976-9 the period of the IMF loan and the Lib-Lab co-operation in government in 1977 until the victory of the Tories in 1979

These political sub-divisions also broadly coincided with the economic sub-divisions.

1970-4 The period of the Heath Government

Early years saw the growth characteristic of the long boom coming to an end. In 1970 wages were rising at 10% per annum and prices at 7% - twice the average for the 1960s.

The Heath government came to power in 1970 attempting to bring down inflation whilst at the same time opposing any attempts to introduce any incomes policy. Heath wished to move away from the tripartite experience of the early 1960s. Labour governments attempt to introduce ‘In Place of Strife’ and place restrictions upon trade unions rights was the major cause of the governments unpopularity in the 1970 election.

Heath wished to see a removal of government from industry and more stringent restrictions on trade union activity.

Attempts to reduce government support for failing industries failed. Throughout the 1970-4 period expenditure on goods and services increased. In part this was due to the resistance government found on the part of those employed in these industries. The occupation of Upper Clyde Shipyards forced government to support the firm, similarly Rolls Royce, although officially bankrupt, was provided with funding to continue production.

It was also due to the problem of rising unemployment generally. Unemployment had been rising in 1970-1 much more quickly than previously. The government in response attempted to reflate the economy with tax cuts and investment grants to industry. These attempts failed to stop unemployment moving towards 1m by 1972.

Further attempts to boost demand were made including the abolition of the ceilings of bank credit. Previously banks had to retain 28% of their liquid assets and hence a limit was placed upon their lending. This was reduced to 12.5% to promote competition amongst lenders. The result was bank lending which had been growing at 12% per annum from 1963-72 now rose 37% in 1972 and 1973 by 43%.

Internationally America had also abandoned fixed exchange rates and the £’s value against other currencies now floated.

Inflationary pressures caused by lessening of sterling’s value led to imported inflation. Inflationary pressures were clearly building up. In response to inflationary pressures trade unions were also making claims for larger pay rises. It was these that caused the first conflict with the miners union the NUM in 1972 and as a result of shortages of coal a three day week.

Between 1972 and 1974 economic policy was aimed at boosting demand to cope with unemployment. Unemployment fell back to 500,000 by 1973 but again began to rise. The Barber Boom as it was called involved increasing public spending whilst reducing taxation. The boom resulted in a worsening of the balance of payments and increasing government borrowing to pay for imports and spending commitments.

In 1974 the economy faced strong demand growth, rising inflationary pressures and an external deficit which was larger than at any time since the war.

The Period 1974-6: The end of Keynesianism

The labour government which came to power in 1974 therefore had significant economic weaknesses to address. Balance of Payments deficit of over £3b, import prices rising at 60% per annum and a public sector deficit of over £3b.

Government was also committed to attempting to restore competitiveness for manufacturing industry through the promotion of tripartite planning agreements. However private industry was increasingly hostile to the continuation of tripartism and government intervention.

The single area to focus upon is the emergence of wage restraint - the Social Contract - or social con-trick as it was widely known.

Trade union leaders agreed to moderate wage bargaining in order to support the government in its anti-inflation measures. The Social Contract had three successive stages. In its first stage it was highly successful. In the first half of 1976 the fall was temporarily to below 10%. In other words the Social Contract imposed tight limits upon workers pay at the same time that inflation was taking longer to decline. The result was that living standards were hit hard.

1976-9 the period of the IMF loan and Lib-Lab co-operation in government in 1977 until the victory of the Tories in 1979

The Social Contract held until 1978-9. The attempt to maintain low wage rises for the third year running failed as Ford workers agreed to a 17% pay increase. Two months afterwards in January 1979 1.5m low paid public sector workers took part in protest strikes to gain better wages. Incomes policy was dead in the water as workers attempted to retain their living standards. Even so in the first six months of 1979 hourly wages rose by less than 10% while retail prices rose 11%.

Incomes policy failed for two reasons:

workers were expected to hold back wages whilst the reduction of inflation took longer. Yet employers who were supposed to control prices were not responding rapidly enough.

The change in government policy towards demand management in 1976 altered attitudes.

The difficulties of financing the continued trade deficit combined with the growth of public expenditure presented difficulties within the financial markets. The first budget in 1974 forecast a PSBR of some £2.73b, the 1975 budget £9b and the 1976 budget £11.96b.

The actual PSBR in 1974 and 1975 in actual fact turned out to be £7.6b and £10.8b. No matter what cuts were made expenditure continued to rise.

The 1976 budget estimates were greeted sceptically by the IMF and holders of sterling. In order to gain finance for the deficit the IMF dictated a series of cuts should be made to social security and welfare.

It was these cuts that led Dennis Healy the Chancellor and Jim Callaghan the Prime Minister to change their economic stance. At the Labour party conference Callaghan made a famous speech which effectively announced the abandonment of Keynesian principles and the acceptance of the arguments from monetarist economists.

He said that the Keynesian option of using government spending to reverse a recession.

‘no longer exists, and that insofar as it ever did exist it only worker on each occasion by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy.’

In other words, to maintain employment through the maintenance of high levels of demand was at an end. In actual fact the PSBR estimates for 1976 were in actual fact correct. The cuts introduced prior to the IMF demands to reduce public expenditure had already worked yet the government accepted the proposals from the IMF and abandoned its commitment to Keynesian vies. The resultant fall in government expenditure was very significant. It was said that the Labour government closed more schools and hospitals than Thatcher ever did.

These closures and cuts again ruptured the belief in a social contract and as a result the winter of discontent was the culmination of a series of conflicts over the restructuring of the British economy.

Inflation and Unemployment

The decade as a whole was dominated by the struggle to contain inflation. The commitment to full employment was slowly abandoned - never to be adopted again.

Dennis Healy in 1975 as Chancellor of the Exchequer

“I fully understand why I have been urged by so many friends both inside and outside the House to treat unemployment as the central problem and to stimulate a further growth in home consumption, public or private, as to start getting the rate of unemployment down as fast as possible. I do not believe it would be wise to follow this advice today… I cannot afford to increase demand further today when 5p in every pound we spend at home has been provided by our creditors abroad and inflation is running at its current rate.”

This was true of all OECD economies and not just Britain. Inflation had been rising since the late 1960s but the oil price shocks of 1973 and 1979 accelerated the ending of the post war boom. Inflation in Britain, using a GDP deflator as a measure of price changes, increased from an average of 4.7% between 1956 and 1973 but from 1973 to 1979 it rose by an average of 14.8%. Amongst OECD economies the same rise was a more modest 8.9%.

Opposition to inflation emerged for a number of reasons. Inflation at 25% in 1974-5 was the highest it had been since WW1. In another sense it caused a moral panic - even before the 1974-5 peak of inflation the Editor of the Times had justified the coup in Chile (which left 50,000 dead and 1 million in exile) on the grounds that ‘there is a limit to the ruin a country can be expected to tolerate’.

Certainly there were sections within the establishment within Britain which thought the country was in grave danger. The move towards concern over inflation derived from harsh economic reality. Unemployment could manifest itself through electoral unpopularity - although the link was much less than supposed. But discontent over inflation would more quickly manifest itself through financial opinion. Financiers don’t worry over unemployment but they certainly do over inflation.

There is a parallel here on the issue of the American loan in 1945-6. The government faced with balance of payments difficulties, large debts and a weak currency were faced with accepting the conditions imposed by the American governments in 1945 and the IMF in 1976.