Acids and Bases (IB)

Theories of Acids and Bases

Acids and bases are chemical substances that interact in specific ways. Different scientists have developed theories to explain how they work. The three main theories are the Arrhenius theory, the Brønsted-Lowry theory, and the Lewis theory.

Arrhenius Theory of Acids and Bases

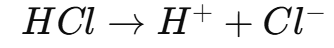

Defined acids as substances that release hydrogen ions (H+) in water.

Defined bases as substances that release hydroxide ions (OH-) in water.

Neutralization occurs when an acid and a base react to form water.

Example:

HCl (acid) dissolves in water to form H+ and Cl-.

NaOH (base) dissolves in water to form Na+ and OH-.

When mixed, H+ and OH- combine to form water: H+ + OH- → H2O.

Limitation: This theory does not explain bases that do not contain OH-, such as ammonia (NH3).

Brønsted-Lowry Theory of Acids and Bases

An acid is a proton donor (gives away H+).

A base is a proton acceptor (takes in H+).

Example:

HCl + NH3 ↔ NH4+ + Cl-

HCl donates a proton (acid), and NH3 accepts it (base).

This theory introduces conjugate acid-base pairs, meaning acids and bases come in pairs that differ by one proton.

Example: NH4+ (acid) and NH3 (base) form a conjugate pair.

Lewis Theory of Acids and Bases

Expands the definitions of acids and bases beyond protons.

A Lewis acid accepts an electron pair.

A Lewis base donates an electron pair.

Example:

BF3 (acid) + NH3 (base) → BF3NH3

This theory explains reactions that don't involve hydrogen ions.

Common Acids and Bases

Acids:

Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

Nitric acid (HNO3)

Sulfuric acid (H2SO4)

Ethanoic acid (CH3COOH)

Carbonic acid (H2CO3)

Phosphoric acid (H3PO4)

Benzoic acid (C6H5COOH)

Bases:

Ammonia (NH3)

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

Potassium hydroxide (KOH)

Calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2)

Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

These are pairs of substances that differ by one hydrogen ion.

Example: NH4+ (conjugate acid) and NH3 (conjugate base).

Acids turn into their conjugate bases after donating a proton, and bases turn into their conjugate acids after accepting a proton.

Amphiprotic and Amphoteric Species

Amphiprotic substances can act as both an acid and a base by either donating or accepting a proton.

Examples:

Water (H2O) can donate H+ to become OH- or accept H+ to become H3O+.

Bicarbonate (HCO3-) can donate a proton to become CO3^2- or accept a proton to become H2CO3.

Amphoteric substances can act as an acid or a base but do not necessarily follow the Brønsted-Lowry definition.

All amphiprotic substances are amphoteric, but not all amphoteric substances are amphiprotic.

Properties of Acids and Bases

Acids and bases have distinct properties and react in specific ways with different substances.

General Properties of Acids and Bases

Property | Acids | Bases |

|---|---|---|

Taste | Sour | Bitter |

pH Level | Less than 7 | Greater than 7 |

Litmus Test | Turns red | Turns blue |

Phenolphthalein | Colorless | Pink |

Methyl Orange | Red | Yellow |

Acid Reactions

Acids react with metals, metal hydroxides, and metal/hydrogen carbonates, producing different products.

Acid-Metal Reaction

General Equation: Acid + Metal → Salt + Hydrogen Gas

Example:

HCl(aq) + Mg(s) → MgCl2(aq) + H2(g)

Acid-Metal Hydroxide Reaction

General Equation: Acid + Metal Hydroxide → Salt + Water

Example:

H2SO4(aq) + Mg(OH)2(s) → MgSO4(aq) + 2H2O(l)

Acid-Metal Carbonate/Hydrogen Carbonate Reaction

General Equation: Acid + Metal Carbonate/Hydrogen Carbonate → Salt + Water + Carbon Dioxide

Example:

NaHCO3(s) + HCl(aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l) + CO2(g)

Acid-Base Neutralization

Neutralization occurs when an acid and a base react to form a salt and water. The reaction is always exothermic, meaning it releases heat.

Neutralization Reaction Example:

Equation: NaOH + HCl → NaCl + H2O

Determining the Salt Formed

Remove a hydrogen ion from the acid.

Remove the hydroxide (OH) or ammonia (NH3) from the base.

Combine the remaining parts to form the salt.

Non-Hydroxide Base Neutralization

Bases can also be oxides or ammonia, which react with acids differently.

Examples:

H2SO4 + 2NH3 → (NH4)2SO4

CuO(s) + H2SO4(aq) → CuSO4(aq) + H2O(l)

Applications of Acids and Bases

Household Cleaners: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) is used to dissolve grease in drains.

Rust Removal: Phosphoric acid (H3PO4) removes rust by converting iron oxide to iron phosphate.

Medical Uses: Antacids, which are basic, neutralize stomach acid.

Acid-Base Titrations

Titrations are a method used to find the concentration of an unknown acid or base by reacting it with a solution of known concentration.

Procedure

A solution with a known concentration (titrant) is placed in a buret.

The solution with the unknown concentration (analyte) is placed in a conical flask.

The titrant is slowly added to the analyte until neutralization occurs.

An indicator is used to determine when the reaction is complete by changing color.

The volume of titrant used is recorded and used to calculate the concentration of the analyte.

Important Terms

Titrant: The solution with a known concentration (acid or base) in the buret.

Analyte: The solution with an unknown concentration in the conical flask.

Equivalence Point: The point at which the moles of acid equal the moles of base, leading to complete neutralization.

Indicator: A substance that changes color at a specific pH, signaling the end of the reaction.

Common Indicators and Their Uses

Indicator | Color in Acid | Color in Base | Used for Titrations Between |

|---|---|---|---|

Phenolphthalein | Colorless | Pink | Strong base & weak acid |

Methyl Orange | Red | Yellow | Strong acid & weak base |

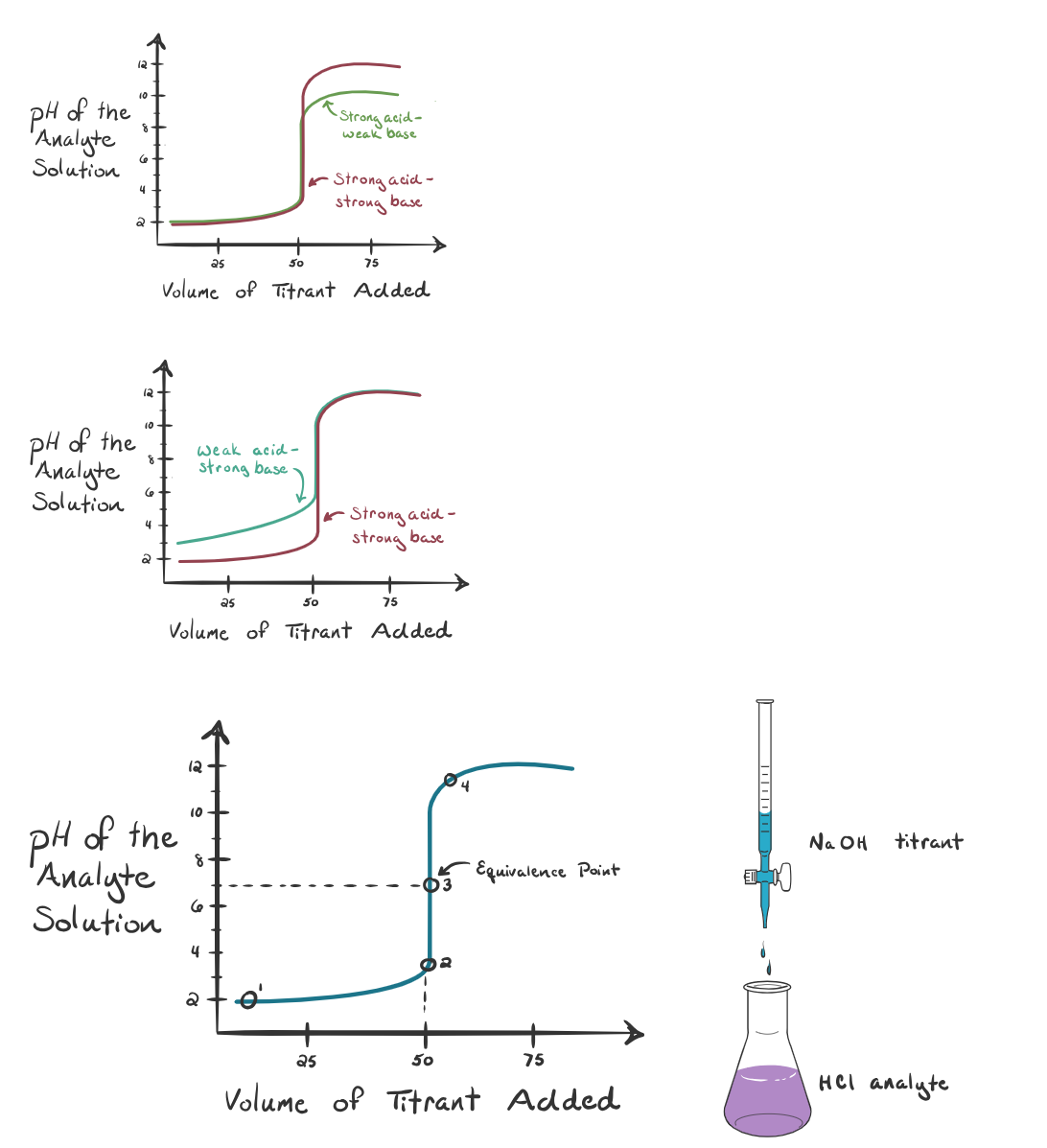

Titration Curve

A titration curve shows how the pH changes as the titrant is added. The steep vertical section represents the equivalence point, where the solution is neutral.

Thermometric Titrations

Since neutralization releases heat, temperature changes can also indicate the equivalence point. The temperature rises during the reaction and stops increasing once neutralization is complete.

Example Calculations

Finding the Concentration of an Acid:

Suppose 25.0 mL of HCl is neutralized by 30.0 mL of 0.10 M NaOH.

Using the formula: M1V1 = M2V2, we solve for M1 (concentration of HCl).

(M1)(25.0) = (0.10)(30.0) → M1 = 0.12 M HCl.

Finding the Concentration of a Base:

Suppose 50.0 mL of NaOH is titrated with 40.0 mL of 0.15 M H2SO4.

Since H2SO4 releases two H+ ions, we use: M1V1 = 2M2V2.

(M1)(50.0) = 2(0.15)(40.0) → M1 = 0.12 M NaOH.

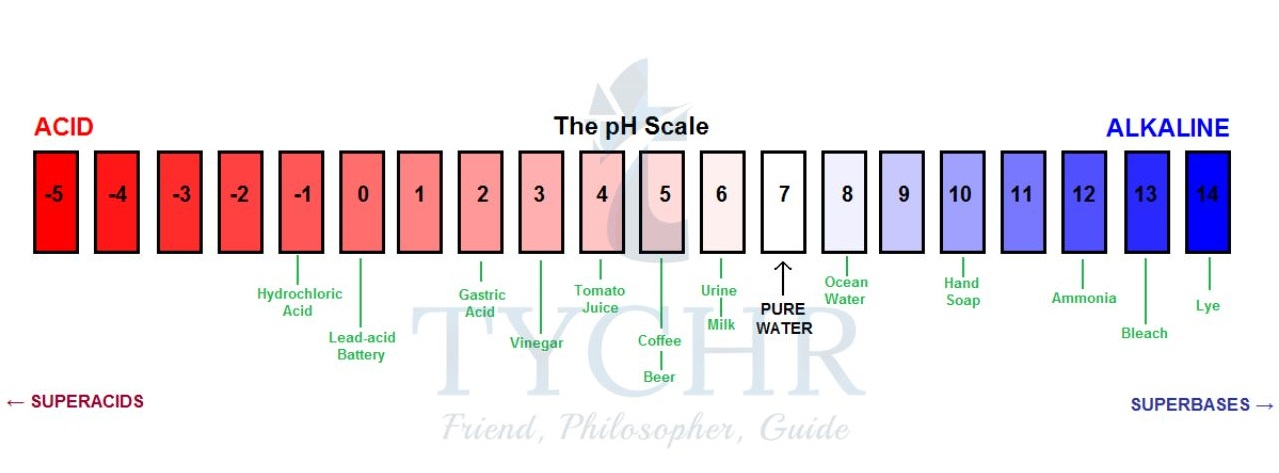

The pH Scale

The pH scale measures how acidic or basic a solution is based on the concentration of hydrogen ions . The scale ranges from 0 to 14:

Acidic solutions have a pH less than 7.

Neutral solutions have a pH of 7.

Basic (alkaline) solutions have a pH greater than 7.

The formula to calculate pH is: This logarithmic scale means that each whole number change represents a tenfold difference in . For example, a solution with a pH of 3 is 10 times more acidic than a solution with a pH of 4.

Examples of pH Calculations

If is 0.01 M: So, the solution is acidic.

If is 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ M: This means the solution is neutral.

The Ionic Product of Water (Kw)

Water can ionize slightly: The equilibrium constant for this reaction at 298K (25°C) is:

This relationship helps us calculate the missing ion concentration when one is known. For example:

If = 1.0 × 10⁻³ M, then: This confirms the solution is acidic.

Buffer Solutions

A buffer is a solution that resists changes in pH when small amounts of acid or base are added. Buffers are made of:

A weak acid and its conjugate base.

A weak base and its conjugate acid.

For example, in the carbonic acid-bicarbonate buffer system: This helps maintain the pH balance in biological systems like blood.

pH Indicators

Indicators are substances that change color depending on pH. Different indicators are used depending on the expected pH range:

Indicator | Color in Acid | Color in Base | Suitable for |

|---|---|---|---|

Litmus Paper | Red | Blue | General pH test |

Phenolphthalein | Colorless | Pink | Weak acid-strong base |

Methyl Orange | Red | Yellow | Strong acid-weak base |

pH Curves and Titrations

A pH curve shows how the pH changes as an acid or base is added. There are four common types of titration curves:

Strong Acid – Strong Base (e.g., HCl and NaOH)

Initial pH is very low (~1)

pH rises gradually, then jumps sharply from ~3 to ~11 at equivalence

Equivalence point is at pH 7

After equivalence, the curve flattens at high pH

Weak Acid – Strong Base (e.g., CH₃COOH and NaOH)

Initial pH is higher than a strong acid (~3–4)

A buffer region exists before equivalence where pH changes slowly

pH jumps from ~7 to ~11 at equivalence

Equivalence point is above pH 7

Strong Acid – Weak Base (e.g., HCl and NH₃)

Initial pH is low (~1)

Buffer region keeps pH steady before equivalence

pH jumps from ~3 to ~7 at equivalence

Equivalence point is below pH 7

Weak Acid – Weak Base (e.g., NH₃ and CH₃COOH)

Initial pH is moderate

pH rises steadily, no sharp jump at equivalence

Equivalence point is difficult to determine

Measuring pH

pH paper/universal indicator: Changes color based on pH and is matched to a color chart.

pH meter: Gives an exact numerical value by detecting concentration

Strong and Weak Acids and Bases

Acids and bases can be classified as strong or weak based on how completely they dissociate (break apart) into ions in water.

Strong acids and bases fully dissociate in water, meaning they completely break into their ions.

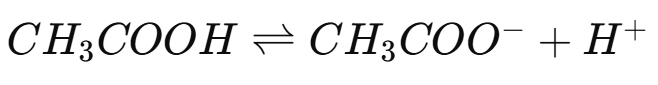

Weak acids and bases only partially dissociate, meaning some molecules remain intact while others break apart.

The pH scale helps measure their strength:

Strong acids have very low pH (close to 0), while strong bases have very high pH (close to 14).

Weak acids and bases have pH values closer to the middle (but still less than 7 for acids and greater than 7 for bases).

Common Strong and Weak Acids and Bases

Type | Examples |

|---|---|

Strong Acids | HCl (Hydrochloric acid), H2SO4 (Sulfuric acid), HNO3 (Nitric acid) |

Weak Acids | CH3COOH (Acetic acid), H2CO3 (Carbonic acid), H3PO4 (Phosphoric acid) |

Strong Bases | NaOH (Sodium hydroxide), KOH (Potassium hydroxide), Ba(OH)2 (Barium hydroxide) |

Weak Bases | NH3 (Ammonia), Mg(OH)2 (Magnesium hydroxide) |

Key Differences Between Strong and Weak Acids/Bases

Property | Strong Acids/Bases | Weak Acids/Bases |

|---|---|---|

pH | Very low (acid) or very high (base) | Closer to neutral but still acidic/basic |

Dissociation | Fully dissociates in water | Partially dissociates in water |

Electrical Conductivity | High (more free ions) | Low (fewer free ions) |

Reaction Rate | Faster reactions | Slower reactions |

Buffers: Controlling pH Changes

A buffer is a solution that resists changes in pH when small amounts of acid or base are added. Buffers work because they contain both a weak acid and its conjugate base (or a weak base and its conjugate acid), which help absorb extra H+ or OH- ions.

Experimental Ways to Identify Strong vs. Weak Acids and Bases

Electrical Conductivity Test:

Strong acids and bases conduct electricity better because they have more free ions.

Weak acids and bases conduct less due to fewer free ions.

Reaction Rate with Metals and Carbonates:

Strong acids react faster with metals (like Mg) and carbonates (like CaCO3), producing hydrogen gas or CO2 quickly.

Weak acids react more slowly.

Measuring pH:

Strong acids have lower pH, and strong bases have higher pH compared to weak ones at the same concentration.

A pH meter or universal indicator can be used to compare acidity or basicity.

Enthalpy of Neutralization: Energy in Reactions

When acids and bases react, they form water and salt, releasing heat (exothermic reaction).

The heat released is nearly the same for all strong acid-strong base reactions because they fully dissociate.

Weak acids and bases release less heat since they only partially dissociate, and some energy is used to break molecules apart.

Misconceptions: Strong vs. Concentrated and Weak vs. Diluted

Strong vs. Weak: Refers to how much the substance ionizes in water.

Example: HCl is strong because it fully ionizes, while CH3COOH is weak because it only partially ionizes.

Concentrated vs. Diluted: Refers to the number of moles of solute per liter of solution (not strength!).

Example: A weak acid can be concentrated if it has many moles per liter, and a strong acid can be diluted if it has very few moles per liter.

Acid Deposition: Causes, Effects, and Prevention

Acid deposition refers to the process where acidic pollutants settle on the Earth's surface. This can occur in two ways:

Wet deposition: Acidic rain, snow, sleet, hail, fog, or mist falls to the ground.

Dry deposition: Acidic particles and gases settle as dust and smoke, later dissolving in water to form acids.

Pure water has a pH of 7.0, but rainwater is naturally slightly acidic (around pH 5.6) due to dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2):

CO2 (g) + H2O (l) ⇌ H2CO3 (aq)

This forms weak carbonic acid, which is a natural process and not considered acid rain.

However, acid rain occurs when sulfur and nitrogen oxides react with water to form strong acids.

Sources of Acid Deposition

Acid rain comes mainly from two elements: sulfur and nitrogen, which form their respective acids:

Sulfuric and Sulfurous Acid Formation

Sulfur oxides come from burning fossil fuels, such as coal and oil, which contain sulfur from ancient organisms. When burned, sulfur reacts with oxygen:

S (s) + O2 (g) → SO2 (g)

SO2 (g) + H2O (l) → H2SO3 (aq) (Sulfurous acid - weak acid)

S (s) + 3O2 (g) → 2SO3 (g)

SO3 (g) + H2O (l) → H2SO4 (aq) (Sulfuric acid - strong acid)

Nitric and Nitrous Acid Formation

Nitrogen oxides are produced in high-temperature environments like combustion engines. Normally, nitrogen and oxygen do not react, but at high temperatures, they can form nitrogen oxides:

N2 (g) + 2O2 (g) → 2NO2 (g)

2NO2 (g) + H2O (l) → HNO3 (aq) + HNO2 (aq)

HNO3 (Nitric acid - strong acid)

HNO2 (Nitrous acid - weak acid)

Effects of Acid Deposition

Acid deposition has serious environmental and health effects.

1. Damage to Buildings and Monuments

Marble and limestone (CaCO3) react with acids, leading to erosion:

CaCO3 (s) + H2SO4 (aq) → CaSO4 (aq) + H2O (l) + CO2 (g)

CaCO3 (s) + 2HNO3 (aq) → Ca(NO3)2 (aq) + H2O (l) + CO2 (g) This weakens structures and causes historic monuments to deteriorate.

2. Harm to Plant Life

Acid rain leaches away important nutrients like magnesium (Mg2+), calcium (Ca2+), and potassium (K+), preventing plants from absorbing them. It also releases toxic aluminum ions (Al3+), which damage roots and hinder plant growth.

3. Damage to Water Ecosystems

Lakes and rivers can become too acidic for aquatic life. Fish species such as trout and perch cannot survive at pH levels below 5. Additionally, aluminum ions released from rocks under acidic conditions interfere with fish gills, reducing their ability to absorb oxygen:

Al(OH)3 (s) + 3H+ (aq) → Al3+ (aq) + 3H2O (l)

Acid rain also contributes to eutrophication, where excess nitrates lead to algal blooms that deplete oxygen, suffocating aquatic organisms.

4. Impact on Human Health

Acid rain does not directly harm humans, but the sulfate and nitrate particles formed can travel long distances, irritating the respiratory system and increasing risks of asthma, bronchitis, and emphysema. It also contributes to the release of toxic metal ions (Al3+, Pb2+, Cu2+) into drinking water, which can be harmful if consumed.

Prevention and Reduction Strategies

Efforts to reduce acid deposition focus on pre- and post-combustion technologies:

Pre-Combustion Methods

These techniques reduce sulfur content in fuels before combustion:

Washing coal to remove sulfur impurities.

Mineral beneficiation (crushing and floating coal to reduce sulfur content), which can remove up to 90% of inorganic sulfur.

Post-Combustion Methods

These methods remove pollutants after combustion:

Catalytic converters in cars reduce nitrogen oxides.

Flue gas desulfurization (scrubbers) use calcium oxide (CaO) to neutralize sulfur dioxide before it is released:

CaO (s) + SO2 (g) → CaSO3 (s)

Switching to cleaner fuels like natural gas and renewable energy sources.

Lewis Acids and Bases

Lewis acids and bases are defined based on how they interact with electron pairs:

A Lewis acid is a substance that accepts a pair of electrons.

A Lewis base is a substance that donates a pair of electrons.

This definition is broader than the Brønsted-Lowry theory, which focuses on proton transfer. While all Brønsted-Lowry acids are also Lewis acids, some Lewis acids do not involve protons at all.

A Lewis acid and a Lewis base form a special type of covalent bond called a coordinate bond, where both electrons in the bond come from the Lewis base.

For example, when ammonia (NH₃) reacts with boron trifluoride (BF₃):

Ammonia (NH₃) has a lone pair on nitrogen, making it a Lewis base.

Boron trifluoride (BF₃) has an empty orbital, so it acts as a Lewis acid.

The nitrogen donates its lone pair to boron, forming a coordinate bond.

Examples of Lewis Acids and Bases

Lewis Acids (Electron Pair Acceptors) | Lewis Bases (Electron Pair Donors) |

|---|---|

BF₃ (Boron trifluoride) | NH₃ (Ammonia) |

AlCl₃ (Aluminum chloride) | OH⁻ (Hydroxide ion) |

H⁺ (Proton) | CN⁻ (Cyanide ion) |

Transition metal ions (Fe³⁺, Cu²⁺) | H₂O (Water), Cl⁻ (Chloride ion) |

Lewis Acids and Bases in Complex Ion Formation

Transition metals often act as Lewis acids because they have partially empty d-orbitals. They form complex ions with molecules or ions that have lone pairs (called ligands), which act as Lewis bases.

For example, when copper (II) ions react with ammonia: Here, Cu²⁺ is the Lewis acid, and NH₃ is the Lewis base.

Nucleophiles and Electrophiles

Nucleophiles ("nucleus-loving") are electron-rich species that donate electrons, just like Lewis bases. Example: OH⁻, NH₃, and CN⁻.

Electrophiles ("electron-loving") are electron-poor species that accept electrons, just like Lewis acids. Example: H⁺, BF₃, and metal ions.

Comparing Lewis and Brønsted-Lowry Theories

Theory | Acid Definition | Base Definition |

|---|---|---|

Brønsted-Lowry | Proton donor | Proton acceptor |

Lewis | Electron pair acceptor | Electron pair donor |

While Brønsted-Lowry acids must contain hydrogen, Lewis acids can include other substances like metal ions or boron compounds. This makes the Lewis definition more general and applicable to more reactions.

Acid-Base Calculations

Strength of Acids and Bases

Acids and bases can be strong or weak, depending on how much they ionize in water.

Strong acids and bases completely ionize in water. For example, hydrochloric acid (HCl) dissociates fully:

If you start with 0.1 M HCl, the concentration of H+ is also 0.1 M.Weak acids and bases only partially ionize. Their equilibrium concentrations must be calculated using an expression called the acid dissociation constant (Ka) or base dissociation constant (Kb).

Ka and Kb

For a weak acid HA dissolving in water:

The expression for Ka is:

For a weak base B :

The expression for Kb is:

Calculating pH for Weak Acids and Bases

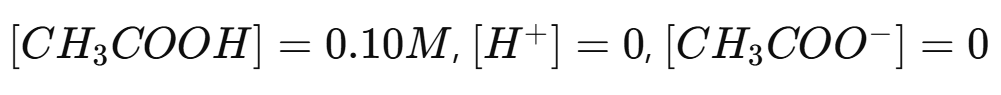

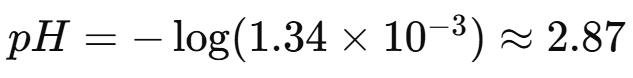

Example 1: Finding the pH of Acetic Acid

Given: 0.10 M acetic acid (CH₃COOH), Ka =

Write the reaction:

Set up an ICE table:

Initial:

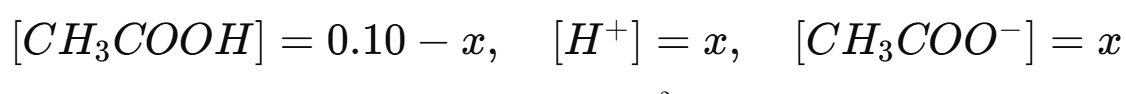

Change: Let x be the amount that ionizes, so at equilibrium:

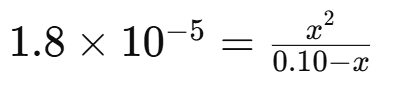

Apply the Ka expression:

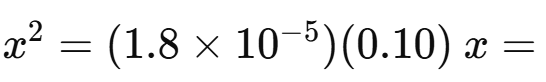

Approximate by assuming is small:

Find pH:

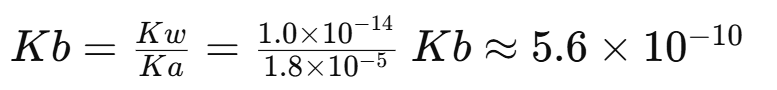

Relationship Between Ka and Kb

For a conjugate acid-base pair: Ka * Kb = Kw where at 25°C.

Example 2: Finding Kb from Ka

Given: Ka of acetic acid = , find Kb of acetate (CH₃COO⁻).

Since acetic acid is a weak acid (small Ka), its conjugate base (acetate) is a weak base (small Kb).

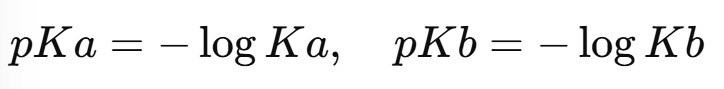

pKa and pKb

Instead of dealing with very small Ka and Kb values, we use:

A lower pKa means a stronger acid, and a lower pKb means a stronger base.

Example 3: Calculating pKa

If Ka of HF is , then:

Temperature Dependence of Kw

Kw is defined as , and at 25°C: At higher temperatures, water ionizes more, increasing Kw and decreasing pH. However, neutrality still means , even if pH is lower than 7.