Before

Asthma

Asthma Pathophysiology

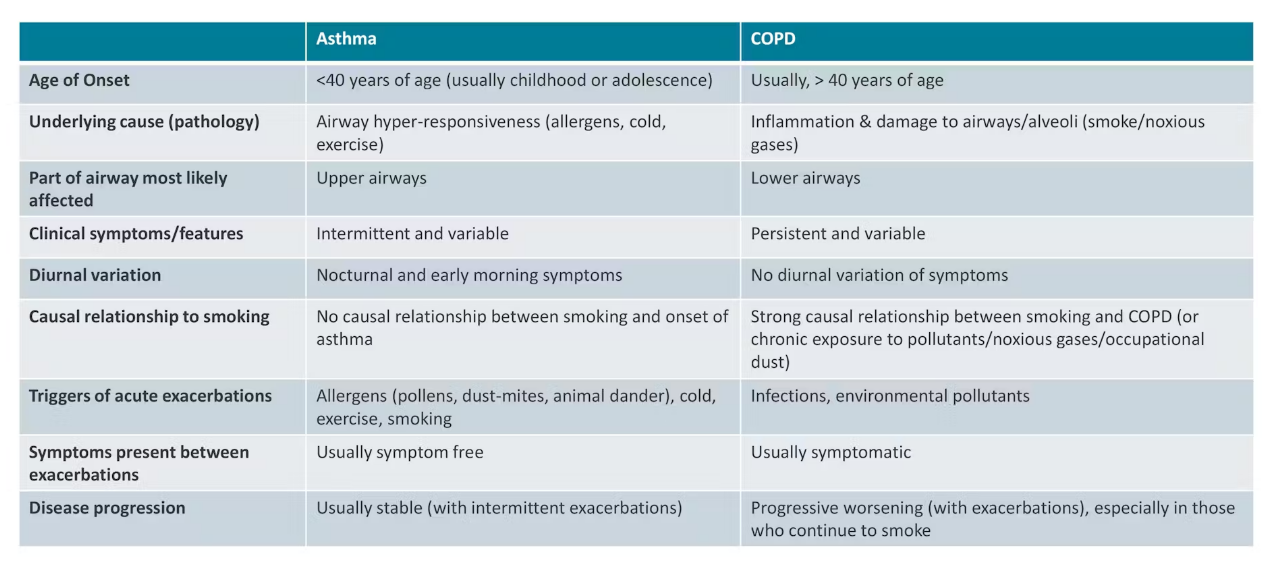

Overview of Respiratory Conditions

Focus on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Presentation by Professor Anna Hutchinson, a critical care and respiratory nurse consultant

Asthma Overview

Prevalence:

Affects approximately 12% of boys and 8% of girls in childhood

In adults over 25, prevalence shifts to 12-16% in women and 8-10% in men

Pathophysiology:

Affects lower respiratory tract

Inflammation of lower airways and acute spasm of bronchial smooth muscles

Results in acute narrowing of airways

Symptoms include:

Wheezing

Shortness of breath

Coughing

Chest tightness

Decreased exercise tolerance

Fatigue

Risk Factors for Asthma

Combination of genetic predisposition and environmental exposure

Common Triggers:

Indoor/outdoor air pollution

Cigarette smoking

Household chemicals and cleaning products

Indoor pollutants (dust, molds, pet dander)

Bacterial and viral infections

Acute changes in weather, e.g., cold air, thunderstorms

Emotional changes (anger, fear)

Hormonal changes (pregnancy)

Physical exercise

Medications (e.g., aspirin, NSAIDs, and beta blockers) can worsen asthma

Thunderstorm Asthma

A unique phenomenon occurring in specific Australian states

Triggered by high pollen counts during hot, dry, and windy conditions

2016 Epidemic in Melbourne:

3,365 hospital presentations and 10 deaths within 30 hours

Development of thunderstorm asthma forecasting system for early warnings

Severity of Asthma

Ranges from mild intermittent symptoms to severe persistent inflammation

Severe cases significantly affect quality of life, exercise capacity, and social participation

Untreated episodes can be life-threatening

Treatment Strategies

Focus on medications to decrease airway inflammation and treat bronchospasm

Further details will be provided in the next video

Reference to additional resources available through the Victorian Health Department.

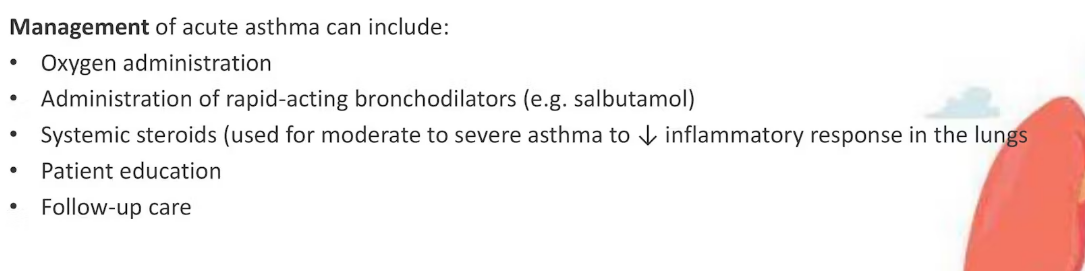

Asthma Management - Treatment

Pathophysiology of Asthma

Two key mechanisms drive the condition:

Inflammation of the Upper Respiratory Tract:

Inflammation of bronchial walls leads to acute narrowing of airways.

Chronic untreated inflammation can cause scarring and decrease lung function.

Acute Bronchospasm:

Caused by smooth muscle contraction in the bronchial tree.

Treatment Goals

Goals of asthma management:

• Prevent and Control asthma symptoms

• Maintain lung function and activity

• Prevent morbidity and mortality

Patient education focuses on:

• Avoidance of triggers

• Pharmacotherapy

• Self-management

Asthma action plans (& regular review):

• written document

• helps people with asthma to detect early warning signs/symptoms of an exacerbation

• provides instructions on how to manage exacerbations

The Asthma action plan should include three parts:

1. Maintenance therapy (when well)

2. Early exacerbation management (when not well)

3. Crisis management (If symptoms worsen - Danger Signs)

Types of Medications

Bronchodilators (Relievers)

Medications for rapid relief of asthma symptoms.

Can be used before exercise to prevent exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

Mechanism of action: relax bronchial smooth muscle (short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs)

Main groups:

Beta-2 Agonists:

Main medications include:

Salbutamol (Ventolin)

Onset time: 2-5 minutes.

Duration of action: 4-6 hours.

Commonly used for acute asthma attacks in community settings.

Terbutaline (Bricilin).

Types:

Short-acting Beta-2 Agonists:

For immediate relief of sudden breathlessness.

Long-acting Beta-2 Agonists:

Maintains action for 12-24 hours, daily dosage for asthma control.

Common examples include Salmeterol and Formoterol.

Preventers

Aim to control asthma symptoms and prevent attacks.

Reduce inflammation, redness, and swelling in airways:

Less sensitivity and lower risk of acute bronchospasm.

Typically delivered as inhalers containing low dosages of corticosteroids routinely (daily)

Mainstay of treatment to address the root causes of asthma symptoms.

"Symptom controller" medications:

Aim: provide long-acting bronchodilation (up to 12 hours)

Mechanism of Action: relax bronchial smooth muscles (long-acting beta- agonists (LABAs))

Administered: once or twice daily

Examples: salmeterol, formoterol (both Beta2-agonists)

Combination Therapies

Used in Australia for moderate to severe asthma treatment.

Combines long-acting bronchodilators with corticosteroids in a single inhaler.

Administered: once or twice daily

Benefits include:

Long-acting reliever to decrease breakthrough symptoms.

Corticosteroid to reduce inflammation in the airways.

Regular use is effective for:

Relieving symptoms.

Stabilizing asthma.

Decreasing the risk of exacerbations.

Improving patient quality of life.

The Nurses Role In Asthma Management

Chapter 1: Introduction to Asthma Management

Overview of Nurses' Roles in Asthma Management

Nurses participate in multidisciplinary teams in primary care settings.

Roles include assessing patients and offering asthma education to improve control.

Diagnosis of Asthma

Involves history, physical examination, ruling out other diagnoses, and spirometry to document airflow limitation.

Identification of asthma triggers is key (e.g., cigarette smoke, allergies, viral infections).

Assessing Asthma Control

Many Australians live with poorly controlled asthma; frequent reliever use (e.g., Ventolin) is often mistaken for normal.

Nurses should engage patients to clarify asthma symptom control and prevention of exacerbations.

Use an evidence-based checklist for assessing control:

Do you wake at night with symptoms?

Do you have symptoms in the morning?

How soon do you need your reliever medication after waking?

How often do you need your reliever during the day?

Are your daily activities or exercise restricted by asthma?

Days off work or school due to asthma in the past couple of weeks?

Chapter 2: Written Asthma Action Plan

Importance of Asthma Action Plans

Action plans should outline key steps during flare-ups, emergency contacts, and therapy.

Emphasize the importance of seeing healthcare professionals if symptoms persist.

Proper Inhaler Use

Correct inhaler technique is crucial; many patients lack proper instruction.

Nurses should observe patients using their inhalers and correct misconceptions.

Resources available for demonstrations of proper inhaler use.

Reviewing the Asthma Action Plan

Nurses should clarify the action plan with patients and families to ensure understanding during emergencies.

Role in community settings: administer medications per action plans and assess treatment responses.

Chapter 3: Signs of Deteriorating Asthma Control

Recognizing Asthma Attacks

Typical signs: increased wheezing, cough, sudden chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

Gradual worsening of symptoms indicated by increased nighttime awakenings or frequent reliever use.

Asthma Emergencies

Define an asthma emergency: sudden severe symptoms, difficulty speaking, or cyanosis (blue lips/fingers).

Immediate action: call an ambulance if relief is not achieved with the inhaler.

Asthma First Aid Steps

Sit the person upright and keep them calm.

Administer four puffs of reliever medication (use a spacer if available).

Wait four minutes and monitor the individual closely.

If still not improving, call an ambulance and repeat salbutamol dosages (four puffs every four minutes).

Chapter 4: Conclusion

Continuous Monitoring

After four minutes, if the person is responding, reassure them while monitoring until normal breathing resumes.

If improvement occurs, follow up with a healthcare provider for check-up.

Asthma First Aid Plans for Different Ages

Review specific first aid plans for adults and children to account for differences in administration methods (e.g., spacer with or without a mask).

Nurses' Crucial Role in Acute Care

Nurses support emergency treatment, assess responses, and provide respiratory care in acute settings (ED, medical wards, ICU).

Further details on managing acute asthma exacerbations will follow.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Overview of COPD Pathology

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD):

A chronic inflammatory disease that leads to obstructive airflow from the lungs.

Symptoms include:

Breathing difficulties

Chronic cough

Increased mucus production

Increased wheezing

Typically results from long-term exposure to irritating gases or particulate matter, most often from cigarette smoke.

Increased risk of developing:

Heart disease

Lung cancer

Other various conditions.

Underlying Conditions

Emphysema:

Characterized by the progressive destruction of alveoli.

Decreases the area available for gas exchange in the lungs, leading to:

Progressive shortness of breath

Decreased exercise tolerance.

Chronic Bronchitis:

Refers to chronic inflammation of the bronchial tubes' lining.

Symptoms include:

Daily cough

Daily mucus production.

Increased risk of:

Lower respiratory tract infections

Pneumonia.

Higher likelihood of requiring frequent hospitalizations for managing exacerbations.

Risk Factors and Exposures

Onset of COPD:

Gradual development over time, often due to a combination of risk factors.

Common exposures that contribute to COPD include:

Tobacco smoke exposure

Occupational exposures

Indoor air pollution

Early life factors such as:

Poor growth in utero

Prematurity

Undertreated childhood asthma.

Alpha-one antitrypsin disorder: Rare genetic condition that leads to early onset and rapid progression of COPD.

Prevalence of COPD

Global Statistics:

In 2019, COPD was the third leading cause of death worldwide.

Almost 90% of COPD deaths in individuals aged 70 and above occur in low and middle-income countries.

COPD in Australia:

Affects both men and women.

Approximately 1 in 13 Australians aged 40 and over have some form of COPD.

About half of these individuals are unaware they have the condition.

Higher prevalence in Indigenous Australians, who are 2.5 times more likely to have COPD than non-Indigenous Australians.

To improve patient outcomes, the following are essential:

Early diagnosis and treatment

Risk factor reduction

Ongoing support to slow disease progression and reduce exacerbation risks.

Diagnosis usually based on:

• History of smoking or exposure to other noxious agents

• FEV1/FVC % (forced expiratory ratio (FER) of ≤70%.

GOLD Stage

FEV₁ (% of predicted value)

Symptoms & Severity

Mild (Stage 1)

≥80%

- May have chronic cough and sputum production.

- Minimal impact on daily life.

- Often undiagnosed at this stage.Moderate (Stage 2)

50-79%

- Worsening breathlessness on exertion.

- Increased cough, sputum production, wheezing.

- May require bronchodilator therapy.Severe (Stage 3)

30-49%

- Significant limitation in daily activities.

- Frequent exacerbations requiring hospitalization.

- Increased risk of respiratory failure.Very Severe (Stage 4)

<30% (or <50% with chronic respiratory failure)

- Extreme breathlessness (even at rest).

- Recurrent exacerbations affecting quality of life.

- May require long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) or mechanical ventilation.• Other Pulmonary function tests (used to measure lung volumes

and gas diffusion)

• Chest x-ray

• Blood gas analysis

• Physical examination

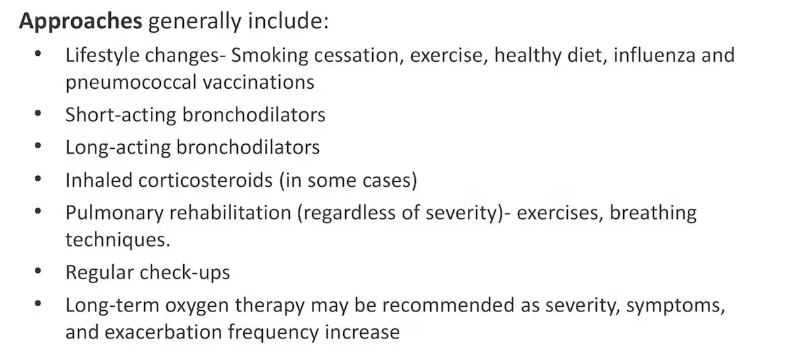

COPD Management

Understanding COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) causes irreversible lung damage.

Early treatment is crucial to enhance quality of life and manage symptoms effectively.

Strategies can be employed to slow progression and minimize flare-ups.

Steps to Improve Quality of Life

Individuals can adopt various approaches for better health and energy, including:

Emotional Self-Care: Focusing on mental and emotional well-being.

Regular Exercise: Essential to prevent muscle weakness and loss of fitness.

Smoking Cessation: Quitting smoking is paramount; it is the most significant lifestyle change one can make.

Importance of Exercise

Everyday Activities: Breathlessness during tasks like walking or washing can deter exercise.

Research Findings: Regular exercise helps:

Maintain fitness

Improve overall well-being

Mitigate symptoms like breathlessness

Pulmonary Rehabilitation:

Specifically designed for individuals with lung conditions.

Programs led by trained specialists (physiotherapists, exercise physiologists).

Tailored to individual fitness levels, emphasizing adaptability rather than traditional exercises.

Benefits of Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Facilitates social interaction and provides a supportive environment.

Improves both physical fitness and mental health.

Teaches essential techniques:

Breathing Techniques: Helps to manage breathlessness.

Sputum Clearance Techniques: Useful for home management.

Post-completion, it is critical to remain active and continue exercise for optimal lung health.

Continuing Support

Lungs in Action Programs:

Offered across Australia, focuses on continued exercise with peers.

Provides a supportive network for those with similar lung conditions.

Emotional Health Considerations

Recognizing that individuals experience COPD differently.

Emotional health directly correlates with symptom severity, affecting social interactions and activity levels.

Importance of maintaining social connections, even during tough days.

Support Groups: Patients are encouraged to seek support from groups or health professionals if feeling overwhelmed.

Additional Health Guidelines

Dietary Approach: Eating a healthy, nutritious diet.

Rest and Sleep: Prioritize sufficient rest and quality sleep.

Vaccinations: Keep vaccinations up-to-date (annual flu shot and pneumonia vaccination) to prevent additional health complications.

Reading Chest X-ray

X-rays are a common diagnostic test used for various conditions and to confirm the position of medical devices such as peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC), intercostal catheters (ICC) and nasogastric tubes.

Interpreting a chest x-ray is an extremely advanced skill however, as a nurse, it is important that you have the ability to identify the normal anatomical structures as well as perform a basic interpretation.

Understanding X-Rays

X-rays are high-energy photons that penetrate body tissues, allowing visualization of internal structures.

They behave similarly to visible light, having reduced penetration in denser materials.

Conventional X-rays display white bones on a black background, resembling photographic negatives:

Dark areas (e.g., lungs) represent regions where more photons penetrate.

Bright white areas show dense bones that block photons.

Importance of a Systematic Approach

Especially crucial for less experienced clinicians.

Reduces chance of missing important findings.

All aspects of interpretation must be included.

Sequence of examination should be logical and easy to remember.

No single best system, but all should start with assessing film quality.

Checklist for Analyzing Chest X-Rays (A to G)

A: Assessment

Begin with patient and exam data verification to avoid errors and ensure the correct study is being examined.

Assess image quality:

Check for proper patient rotation by ensuring medial ends of spinous processes are equidistant from vertebral body borders.

Evaluate inspiration quality; the film should show at least the 10th or 11th ribs for full lung expansion.

Ensure exposure is adequate; adjust brightness to visualize fine lung markings clearly.

Check for air in unintended locations (e.g., pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum). This is crucial for diagnosing surgical emergencies relative to air presence.

B: Bones

Inspect both clavicles and all 12 pairs of ribs for:

Fractures

Deformities

Missing bones

Examine body wall and soft tissues for swelling, masses, or irregularities; often overlooked.

C: Cardiac Silhouette and Size

Assess the cardiac silhouette:

Features include the right atrium, left ventricle, and atrial appendage.

Orientation: Right atrium appears on the left side of the X-ray; left ventricle is on the right.

Normal heart size should be less than 50% of the rib cage's greatest diameter; larger sizes may indicate pathology.

D: Diaphragms

Diaphragms should be symmetric, with appropriate contour.

In lateral views:

Estimate that a normal hemidiaphragm is 1.5 centimeters above the line connecting costophrenic and sternophrenic angles.

E: Equipment and Effusions

Note the placement of lines, tubes, and wires associated with life support:

Endotracheal tubes should be centered in the trachea, at least 2 cm from the tracheal bifurcation.

Nasogastric tubes should be positioned within the stomach.

Check for pleural effusion:

Fluid at costophrenic angles indicates blunting, affecting diagnostic interpretation.

F: Lung Fields

Lung fields should appear symmetric with the absence of:

Haziness

White dots or blotches

Use frontal and lateral X-rays to localize abnormalities:

Example: A nodular mass in the left lung's anterior segment can often be confirmed with CT scans.

G: Great Vessels

Evaluate positioning and size of the great vessels:

Key structures: superior and inferior vena cava, ascending aorta, aortic arch, pulmonary artery, descending aorta.

Orientation: Aortic arch should be positioned highest on the left side; other heart structures should be correctly aligned.

Deviations may indicate underlying congenital issues or disease.

Recap of ABCDEFG Checkpoints

A: Assessment of data, quality, and identifying air abnormalities.

B: Bones in the body wall condition.

C: Cardiac silhouette measurement and size assessment.

D: Diaphragm evaluation for symmetry and flatness.

E: Check equipment placement and effusions.

F: Analysis of lung fields for symmetry and abnormalities.

G: Assessment of the great vessels' position and size.

Focus of the video: systematic approach and normal chest X-ray anatomy.

Learning objectives:

Familiarity with systematic approach for interpreting chest X-rays.

Understanding the correlation between anatomy and normal shadows on an X-ray.

ABCDEF System for Chest X-ray Interpretation

Informally referred to in teaching as the ABCDEF system.

Commonly used in the US, though not perfect.

Breakdown of the system:

A: Airways - trachea in midline, right & left main bronchus.

B: Bones and Soft Tissue - assessment of visible bones.

C: Cardiac Silhouette and Mediastinum - various structures of the heart.

D: Diaphragm - includes gastric air bubble.

E: Effusions - assessment of the pleura.

F: Fields - examination of the lung fields.

Additional consideration: assessing lines, tubes, devices, and prior surgeries.

Lungs evaluated near the end to avoid distraction from significant abnormalities.

Airway Structures (A)

Key anatomical structures visible on normal X-ray:

Trachea - located midline.

Right Main Bronchus - more vertical angle.

Left Main Bronchus - more horizontal angle.

Implications:

Increased likelihood of foreign body aspiration into right lung.

Risk of endotracheal tube misplacement into right bronchus.

Bones and Soft Tissue (B)

Identifiable bones on PA/lateral X-ray:

Ribs: posterior and anterior components.

Clavicles: right and left visible.

Sternum: may be obscured on lateral view.

Vertebral Bodies: usually visible on PA when quality is adequate.

Cardiac Silhouette and Mediastinum (C)

Components to evaluate:

Shapes and sizes forming the cardiac silhouette.

Notable structures include the aortopulmonary window (location for recurrent laryngeal nerve and lymph nodes).

Visualization techniques:

Use drawings for anatomy understanding.

Diaphragm and Pleura (D)

Diaphragm characteristics:

Right hemidiaphragm generally higher due to liver.

Curvature represents 3D structure; assess both views.

Pleura:

Surrounds lungs, usually invisible due to thinness.

Costophrenic angles:

Right and left angles assess pleural spaces.

Posterior costophrenic angle visible on lateral.

Gastric air bubble under left hemidiaphragm indicates stomach position.

Lung Fields and Fissures (F)

Structures to examine in lungs:

Fissures:

One horizontal fissure visible on right, not usually visible in left lung.

Two oblique fissures on right, and one on left.

Lobes:

Right lung: divided into three lobes (upper, middle, lower).

Left lung: divided into two lobes (upper, lower).

Fissure visibility aids in localization of lung abnormalities.

Passive Smoking & Its Impact on Asthma and COPD

Passive smoking (also known as secondhand smoke) occurs when a person inhales smoke from burning tobacco products or exhaled smoke from a smoker. It contains harmful chemicals like carbon monoxide, nicotine, formaldehyde, and benzene, which can damage lung tissue and trigger respiratory conditions.

Here’s how passive smoking affects asthma and COPD:

Impact of Passive Smoking on Asthma

Trigger for Asthma Attacks – Secondhand smoke is a common asthma trigger, leading to bronchoconstriction, inflammation, and excess mucus production.

Increased Severity & Frequency of Attacks – Children exposed to secondhand smoke have more frequent and severe asthma attacks than those in smoke-free environments.

Higher Risk of Developing Asthma – Long-term exposure to passive smoke increases the risk of developing asthma, especially in children.

Reduced Response to Treatment – Asthma patients exposed to secondhand smoke often respond poorly to medications, such as inhaled corticosteroids.

💡 Key Point: Passive smoking does not cause asthma directly, but it significantly worsens symptoms, increases attacks, and reduces treatment effectiveness.

Impact of Passive Smoking on COPD

Increased Risk of Developing COPD – Long-term exposure to secondhand smoke can lead to chronic bronchitis, airway inflammation, and lung damage, increasing the risk of COPD later in life.

Accelerated Lung Function Decline – Even in non-smokers, exposure to secondhand smoke can cause irreversible lung damage, leading to progressive airway obstruction.

More Frequent COPD Exacerbations – Passive smoking worsens COPD symptoms, leading to more frequent flare-ups, hospitalizations, and faster disease progression.

Increased Mortality Risk – Studies suggest that long-term secondhand smoke exposure raises the risk of premature death in COPD patients.

💡 Key Point: Passive smoking is a major risk factor for COPD, contributing to its development, worsening symptoms, and faster disease progression.

Updated Table Including Passive Smoking:

Category | Asthma | COPD |

|---|---|---|

Age of Onset | Often childhood or adolescence | Usually after 40 years old |

Underlying cause (pathology) | Chronic inflammation due to allergens or irritants | Chronic inflammation due to long-term exposure to irritants (e.g., smoking) |

Part of airway most likely affected | Bronchi (large airways) | Small airways and alveoli |

Clinical symptoms/features | Wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough (episodic) | Chronic cough, sputum production, progressive breathlessness |

Diurnal variation | Symptoms often worse at night or early morning | Less variation, symptoms persistent |

Causal relationship to smoking | Not directly related (though can be worsened by smoking, including passive smoking) | Strongly linked to smoking and secondhand smoke exposure |

Triggers of acute exacerbations | Allergens, cold air, exercise, respiratory infections, passive smoking | Infections, air pollution, smoking, passive smoking, environmental exposure |

Symptoms between exacerbations | Often asymptomatic or mild symptoms | Persistent symptoms even between exacerbations |

Disease progression | - Symptoms are usually intermittent and reversible.- Poor control can lead to airway remodeling, making asthma less reversible.- Severe exacerbations can cause respiratory failure, but long-term lung damage is rare with proper treatment. | - Symptoms worsen gradually over time.- Permanent airflow limitation due to fibrosis, airway remodeling, and alveolar damage.- Exacerbations accelerate lung decline, leading to chronic respiratory failure.- Often leads to high mortality in severe stages. |

Reason for Airway Blockage | Inflammation & swelling of the airway walls, bronchoconstriction, and excess mucus production block airflow. The narrowing is reversible with treatment. | Chronic inflammation, structural changes (fibrosis & scarring), mucus hypersecretion, and alveolar damage (leading to trapped air) cause permanent and progressive airway blockage. |

Impact of Passive Smoking | - Triggers asthma attacks and worsens symptoms.- Increases severity and frequency of attacks.- Raises the risk of asthma development, especially in children.- Reduces effectiveness of asthma medications. | - Major risk factor for COPD development.- Causes permanent lung damage, even in non-smokers.- Speeds up disease progression and increases exacerbations.- Increases the risk of premature death in COPD patients. |

Final Thoughts

Asthma patients exposed to secondhand smoke experience more severe attacks and reduced treatment effectiveness.

COPD patients exposed to secondhand smoke suffer faster lung decline, more hospitalizations, and increased mortality risk.

Avoiding passive smoking is critical for managing both conditions and preventing long-term lung damage.

Let me know if you need any further additions! 😊

Category | Asthma | COPD |

|---|---|---|

Age of Onset | Often childhood or adolescence | Usually after 40 years old |

Underlying cause (pathology) | Chronic inflammation due to allergens or irritants | Chronic inflammation due to long-term exposure to irritants (e.g., smoking) |

Part of airway most likely affected | Bronchi (large airways) | Small airways and alveoli |

Clinical symptoms/features | Wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough (episodic) | Chronic cough, sputum production, progressive breathlessness |

Diurnal variation | Symptoms often worse at night or early morning | Less variation, symptoms persistent |

Causal relationship to smoking | Not directly related (though can be worsened by smoking, including passive smoking) | Strongly linked to smoking and secondhand smoke exposure |

Triggers of acute exacerbations | Allergens, cold air, exercise, respiratory infections, passive smoking | Infections, air pollution, smoking, passive smoking, environmental exposure |

Symptoms between exacerbations | Often asymptomatic or mild symptoms | Persistent symptoms even between exacerbations |

Disease progression | - Symptoms are usually intermittent and reversible.- Poor control can lead to airway remodeling, making asthma less reversible.- Severe exacerbations can cause respiratory failure, but long-term lung damage is rare with proper treatment. | - Symptoms worsen gradually over time.- Permanent airflow limitation due to fibrosis, airway remodeling, and alveolar damage.- Exacerbations accelerate lung decline, leading to chronic respiratory failure.- Often leads to high mortality in severe stages. |

Reason for Airway Blockage | Inflammation & swelling of the airway walls, bronchoconstriction, and excess mucus production block airflow. The narrowing is reversible with treatment. | Chronic inflammation, structural changes (fibrosis & scarring), mucus hypersecretion, and alveolar damage (leading to trapped air) cause permanent and progressive airway blockage. |

Impact of Passive Smoking | - Triggers asthma attacks and worsens symptoms.- Increases severity and frequency of attacks.- Raises the risk of asthma development, especially in children.- Reduces effectiveness of asthma medications. | - Major risk factor for COPD development.- Causes permanent lung damage, even in non-smokers.- Speeds up disease progression and increases exacerbations.- Increases the risk of premature death in COPD patients. |

Asthma vs COPD

Category | Asthma | COPD |

|---|---|---|

Age of Onset | Often childhood or adolescence | Usually after 40 years old |

Underlying cause (pathology) | Chronic inflammation due to allergens or irritants | Chronic inflammation due to long-term exposure to irritants (e.g., smoking) |

Part of airway most likely affected | Bronchi (large airways) | Small airways and alveoli |

Clinical symptoms/features | Wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough (episodic) | Chronic cough, sputum production, progressive breathlessness |

Diurnal variation | Symptoms often worse at night or early morning | Less variation, symptoms persistent |

Causal relationship to smoking | Not directly related (though can be worsened by smoking, including passive smoking) | Strongly linked to smoking and secondhand smoke exposure |

Triggers of acute exacerbations | Allergens, cold air, exercise, respiratory infections, passive smoking | Infections, air pollution, smoking, passive smoking, environmental exposure |

Symptoms between exacerbations | Often asymptomatic or mild symptoms | Persistent symptoms even between exacerbations |

Disease progression | - Symptoms are usually intermittent and reversible.- Poor control can lead to airway remodeling, making asthma less reversible.- Severe exacerbations can cause respiratory failure, but long-term lung damage is rare with proper treatment. | - Symptoms worsen gradually over time.- Permanent airflow limitation due to fibrosis, airway remodeling, and alveolar damage.- Exacerbations accelerate lung decline, leading to chronic respiratory failure.- Often leads to high mortality in severe stages. |

Reason for Airway Blockage | Inflammation & swelling of the airway walls, bronchoconstriction, and excess mucus production block airflow. The narrowing is reversible with treatment. | Chronic inflammation, structural changes (fibrosis & scarring), mucus hypersecretion, and alveolar damage (leading to trapped air) cause permanent and progressive airway blockage. |

Impact of Passive Smoking | - Triggers asthma attacks and worsens symptoms.- Increases severity and frequency of attacks.- Raises the risk of asthma development, especially in children.- Reduces effectiveness of asthma medications. | - Major risk factor for COPD development.- Causes permanent lung damage, even in non-smokers.- Speeds up disease progression and increases exacerbations.- Increases the risk of premature death in COPD patients. |

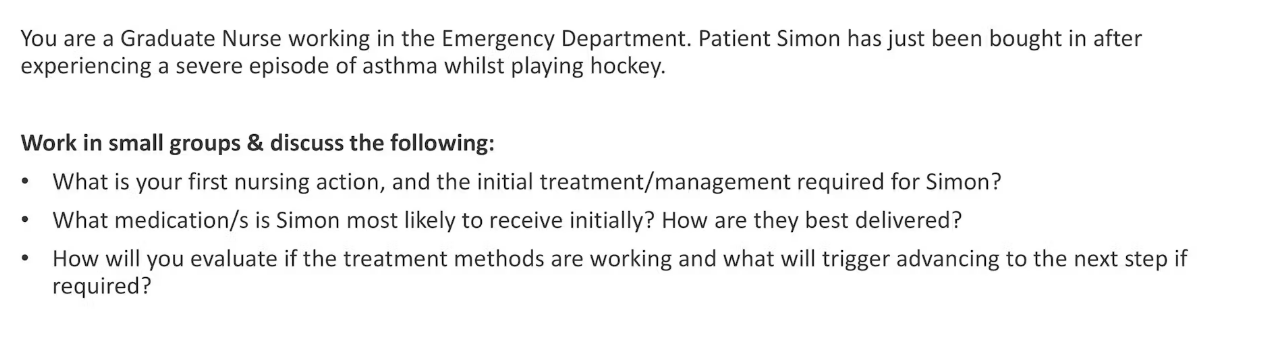

Case Study

1. First Nursing Action & Initial Treatment/Management for Simon

Rapid Assessment (ABCDE Approach)

Airway: Ensure the airway is open and not obstructed.

Breathing: Assess respiratory rate, oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and auscultate lung sounds for wheezing or silent chest (a dangerous sign of severe obstruction).

Circulation: Monitor heart rate and blood pressure (tachycardia may indicate hypoxia or medication side effects).

Disability: Assess consciousness level (severe hypoxia can lead to confusion or agitation).

Exposure: Identify any environmental triggers (e.g., cold air, allergens).

Administer Oxygen Therapy (if required)

If oxygen saturation <92%, administer high-flow oxygen (via non-rebreather mask at 6-8 L/min) to prevent hypoxia.

Positioning

Sit Simon in an upright position to ease breathing and lung expansion.

Monitor for Life-Threatening Signs

Silent chest (no wheezing, no air entry)

Severe fatigue or confusion (signs of respiratory failure)

Cyanosis (blue lips or fingers)

Respiratory rate >25 or <8 breaths per minute

Unable to speak in full sentences

If any of these signs are present, urgent escalation to critical care is required.

2. Medications Simon is Most Likely to Receive Initially & Delivery Method

1st Line: Short-Acting Beta-2 Agonist (SABA) – Salbutamol (Ventolin)

How is it delivered?

Nebulizer (preferred in severe asthma): 5mg salbutamol nebulized with oxygen, repeated every 20 minutes as needed.

Metered-Dose Inhaler (MDI) with Spacer: 4-10 puffs, repeated every 20 minutes for 1 hour.

Purpose: Quickly relaxes airway muscles, relieving bronchoconstriction.

2nd Line: Anticholinergic – Ipratropium Bromide (Atrovent)

How is it delivered?

Via nebulizer (500 mcg every 20-30 minutes for up to 3 doses).

Purpose: Provides additional bronchodilation, especially in severe cases.

3rd Line: Systemic Corticosteroids – Prednisolone or IV Hydrocortisone

How is it delivered?

Oral Prednisolone: 40-50 mg once daily for 5 days.

IV Hydrocortisone (if unable to take oral medication): 100mg every 6 hours.

Purpose: Reduces airway inflammation and prevents further exacerbation.

If No Improvement:

Consider IV Magnesium Sulfate (1.2-2g over 20 minutes) for severe cases or IV Prednisolone

Epinephrine (IM Adrenaline) if there is suspicion of anaphylaxis or if the patient is not responding to usual treatment.

3. Evaluating Treatment Effectiveness & When to Escalate Care

Monitor Improvement:

Signs of Recovery:

Reduced respiratory rate

Improved oxygen saturation (>95%)

Reduced wheezing, ability to speak in full sentences

Decreased use of accessory muscles (less chest retraction)

Peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) improving toward baseline

Signs Treatment Is Not Working (Requires Escalation):

Persistent severe breathlessness despite treatment

Deteriorating SpO₂ (<90%) even with oxygen support

Silent chest (no wheezing, no air movement)

Exhaustion, confusion, or drowsiness (impending respiratory failure)

Blood gas abnormalities (respiratory acidosis, CO₂ retention)

🚨 If Simon Deteriorates Further:

Escalate to ICU for ventilation support (Non-Invasive Ventilation or Intubation)

Consider ICU referral if continuous nebulization, IV therapy, and oxygen therapy do not stabilize the patient.

Conclusion

Immediate interventions: Oxygen, bronchodilators (salbutamol + ipratropium), and corticosteroids.

Delivery method: Nebulizer for severe cases, inhaler/spacer if moderate.

Monitor for response: If persistent severe symptoms, consider IV therapy or ICU escalation.

Knowt

Knowt