AP European History Unit 1

1.1-1.2 Renaissance and Northern Renaissance

Contextualizing the Renaissance

Geographically and economically, Italy was at the center of the Mediterranean Sea, making it also central for trade

Because of this, many Italian city-states, particularly Florence, was affluent enough to support the Renaissance that began in Italy.

Socially, Western Europe was recovering from the Black Death

killed about 40 percent of the population

Italy often had wealthy elites, often the family blending of aristocrats and wealthy merchants. The family was patriarchal, and marriages were often arranged. Step-parents were the norm and there were often blended families.

Politically, Italy was a collection of small and large city-states, with no real centralized authority

Religiously, life was centered around life in the Catholic Church, which had withstood the Great Schism in the 14th century.

Intellectually, cities would attract trade, and along with this ideas and culture would follow.

Artists could imitate classical ideas, allowing for the “rebirth” that some historians would argue defines the period.

Wealth and Power in Renaissance Italy

How did politics and economics shape the Renaissance?

The Renaissance was a period of commercial, financial, political, and cultural achievement in two phases, from 1050 to 1300 and from 1300 to about 1600.

The northern Italian cities led the commercial revival, especially Venice, Genoa, and Milan.

Venice had a huge merchant marine; improvements in shipbuilding enhanced trade. These cities became the crossroads between northern Europe and the East.

The first artistic and literary flowerings of the Renaissance appeared in Florence. **Florentine mercantile families dominated European banking.

The wool industry was the major factor in the city’s financial expansion and population increase.

Northern Italian cities were communes—associations of free men seeking independence from the local lords.

The nobles, attracted by the opportunities in the cities, often settled there and married members of the mercantile class, forming an urban nobility.

The popolo, or common people, were disenfranchised, heavily-taxed, and excluded from holding political office. The occasional popolo-led republican governments failed, which led to the rule of despots (signori) or oligarchies.

In the fifteenth century, courts of the rulers were centers of wealth and art and afforded signori and oligarchs the opportunity to display and assert their wealth and power.

Italy had no political unity; it was divided into city-states such as Milan, Venice, and Florence, the Papal States, and the kingdom of Naples in the south.

Though Venice was a republic in name, an oligarchy of merchant-aristocrats ran the city and elected a Doge (Duke) from among themselves.

Milan was also called a republic but was in fact ruled by the Sforza family.

Likewise in Florence, though a republic in name, it was ruled by the Medici family.

The Papal States were ruled by the Pope and the Kingdom of Naples was controlled by the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon.

The major Italian powers controlled the smaller city-states, such as Siena, Mantua, Ferrara, and Modena, and competed furiously among themselves for territory.

The political and economic competition among the city-states prevented centralization of power.

After 1494 a divided Italy became a European battleground. The most famous were the became a European battleground. The most famous were the Habsburg-Valois wars between the German house of Habsburg and the French house of Valois. Italy will not achieve political unification until 1870.

Intellectual Change

The Renaissance was a time when there was a conviction that educated Italians were living in a new era, but that era rested on a deep interest in ancient Greek and Latin literature.

Petrarch, the father of humanism, first advocated delving into the classical past and believed he was witnessing a new era where the glory of ancient Rome would be recaptured. The study of the classics would be known as humanism

A new era, one that would recapture the glory of ancient Greece and Rome was advocated by individuals known as humanists. This was the primary intellectual component of the Renaissance and they advocated that human nature and achievements were worthy of contemplation, downplaying the importance of the church and an afterlife.

Under the patronage of the Medici family, humanists began to explore the ideas in ancient Greek philosophy, reading works from Plato and other philosophers. Man’s divinely bestowed nature meat there were no limits to human potential, so religion remained important, but was often viewed as a springboard to greater individual accomplishments.

Humanists believed in the quality of virtu, ability to shape the world to one’s will, and there were different strands of humanism that would eventually be reflected in the art and philosophy of the Renaissance.

Secularism is a focus on the present and a turning away from concern about the afterlife. The idea persisted that humans could gain rewards in the present and art would take on an increased emphasis on human beings apart from God and the afterlife.

Individualism dealt with a similar concept, that individuals in the present were important and worthy of study, but also went beyond this to embrace the idea that human concerns were worthy of attention and consideration.

Niccolo Machiavelli, one of the most famous figures of the Renaissance, wrote The Prince, a book dedicated to the Medici family. This served as a model for political behavior. The Prince is often considered the first modern work of political science.

Baldassare Castiglione wrote the Book of the Courtier, a secular model for individual behavior and a manual for how a “Renaissance Man’ should behave. He believed that a man needed to be read in the classics and know how to conduct himself in public, but that subjects such as math and science were reserved for men.

Pico della Mirandola wrote his Oration on the Dignity of Man, which was a classic statement on human potential and a revival of Plato’s philosophy.

1.3-1.4 Northern Renaissance and Printing

Art and the Artist

During the early Renaissance, works were often commissioned by large urban groups to showcase their power and influence in the community. The commission for the dome on the cathedral of Florence was given to Filippo Brunelleschi by the Florentine cloth merchants.

In the late 15th century, wealthy individuals and rulers began to sponsor art, still seeking to show their status. Merchants and bankers, popes and princes spent vast sums of money on art.

During the Middle Ages, artists were considered craftsmen and much of the art was anonymous. However, in the Renaissance, artists were regarded as creative geniuses and were sought after for commissions based on their reputations.

New techniques and mediums in art emerged during the Renaissance. Oil paints were used, and naturalism showed as painters and sculptors emphasized anatomy and movement of the human body. A rediscovery of optics and geometry allowed painters to achieve linear perspective and realistic, three-dimensional works.

Leonardo da Vinci is regarded as the foremost “Renaissance Man” - someone who is a multitalented individual. He was known as a painter and a sculptor and was interested in engineering, science, and human anatomy.

He produced hundreds of drawings as a tool for scientific investigation, planning hundreds of inventions that would not be invented for centuries, such as the helicopter, tank, and machine gun.

His most famous portrait, The Mona Lisa, shows a woman with a mysterious smile, the subject for which continues to be debated. Another of his famous paintings, The Last Supper, is a work he considered unfinished.

Michelangelo was also both a painter and a sculptor, left Florence to travel to Rome in about 1500. Wealthy cardinals and popes wanted art to show the power of the church and Michelangelo was commissioned to paint the ceiling and altar wall for the Sistine Chapel.

The alter wall, with its depiction of The Last Judgement, is done in the style of mannerism, where artists use exaggerated musculature, distorted figures, and heightened color to express depth of emotion and drama.

His sculpture of David shows classical Greek inspiration and showcases the glory of man and the human form.

Raphael was the youngest of the great masters. He was also from Florence, but was frequently commissioned to do work in Rome, where the center of new art had shifted in the early 16th century.

Raphael painted hundreds of portraits and devotional images and became highly sought-after for his work. He was commissioned by Pope Julius II to paint The School of Athens, which honors both ancient Greek philosophers and his contemporary artists.

Raphael also painted numerous images of the Madonna, the Mother of Jesus

Art produced in northern Europe was usually more religious than art produced in Italy.

Flemish painters such as Jan van Eyck were considered the artistic equals of Italian Renaissance painters. He was one of the earliest artists to use oil paints and his portraits show realism and attention to detail and the human personality.

Northern Renaissance painters also depicted scenes of everyday life which included villages, peasants, agriculture, and customs and traditions that surrounded small communities. Pieter Bruegel the Elder created many scenes of peasant and village life.

The Renaissance Outside Italy

In the late 15th century students from northern Europe studied in Italy and brought the “new learning” back to their own countries.

These Christian humanists thought that the best elements of classical and Christian cultures should be combined.

These Christian humanists thought that the best elements of classical and Christian cultures should be combined.

Classical ideals of calmness, stoical patience, and broad-mindedness should be joined in human conduct with the Christian virtues of love, faith, and hope.

Thomas More (1478-1535) of England argued that reform of social institutions could reduce or eliminate corruption and war.

More’s, Utopia (1516) describes a community on an island somewhere beyond Europe where all children receive a good education and adults divide their day by work and intellectual activities.

The Dutchman Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) was an expert in the Bible and Greek language who believed that all Christians should read the Bible.

Erasmus's long list of publications includes The Education of a Christian Prince (1504) and The Praise of Folly (1509).

Two fundamental themes run through all of Erasmus’s work: education is the means to reform, and Christianity is an inner attitude of the heart and spirit.

The Printed Word

Around 1455 in the German city of Mainz, Johan Gutenberg (a metal-smith) and two other men invented the movable type printing press – similar to woodblock printing techniques that originated in China and Korea centuries earlier.

Methods of paper production had reached Europe in the 12th century from China through the Near East.

Printing made government and Church information and propaganda much more practical, created an invisible “public” of readers, and increased literacy among lay people.

It’s estimated that within 50 years of the publication of Gutenberg’s Bible in 1456, somewhere between 8 million and 20 million books were printed. This number is far greater than the number of books produced in ALL of Western history up to that point.

Printers created professional reference books for lawyers, doctors, and students, and historical romances, biographies, and how-to manuals for the general public.

Social Hierarchies

Renaissance Italy was built on the divisions that existed in the Middle Ages that divided nobles and common people, but also these new concepts that would divide race, class, and gender.

Beginning in the 15th century, slavery had been a part of Europe, as Portuguese sailors had brought African slaves to markets in Italy and Spain.

A hierarchy based on wealth was emerging in the 14th and 15th centuries, particularly in the cities where a wealthy merchant class often had more money than titled nobilities. Nobles remained prominent and many merchants would purchase titles of nobility or marry their children into noble families

Toward the end of the 14th century, intellectuals began the querelle des femmes, the debate about women. Though women faced barriers to intellectual pursuits, there were several respected female humanists. Women were generally confined to the domestic sphere and the type of education men could receive was off-limits to them.

1.4-1.6 New Monarchy, Exploration

New Monarchies - France

Some scholars have viewed Renaissance kingship as a new form, citing the dependence of the monarch on urban wealth and the ideology of the “strong king.”

France emerged from the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) and the Black Death drastically depopulated, commercially ruined, and agriculturally weak.

Charles VII (r. 1422-1461) created the first permanent royal army, and allowed increased influence in his bureaucracy to lawyers and bankers who established by new taxes on salt (gabelle) and land (taille)

He also asserted his right to appoint bishops in the Pragmatic Sanction of Bourges and through later agreements with the papacy such as the Concordat of Bologna.

Charles’s son Louis XI (r. 1461-1483), aka the “Spider King,” fostered industry from artisans, taxed it, and used the funds to expand his army. He brought much new territory under direct Crown rule.

New Monarchies - Spain

Although Spain remained a confederation of kingdoms until 1700, the wedding of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon did lead to some centralization.

Similar to France, Ferdinand and Isabella curbed aristocratic power by excluding high nobles from the royal council and recruited lesser nobles onto their royal council; which had full executive, judicial, and legislative powers under the monarchy.

From the Spanish Borgia pope, Alexander VI, they secured the right to appoint bishops in Spain and in the Spanish empire in America, enabling them to establish the equivalent of a national church.

With the revenues from ecclesiastical estates they were able to expand their territories to included the remaining land held by Arabs in southern Spain.

Conversos (those who are newly converted to Christianity – aka New Christians) were often well educated and held prominent positions in government, the church, medicine, law, and business. New Christians and Jews in 15th century Spain exercised influence disproportionate to their numbers – their success bred resentment.

Popular anti-Semitism increased in 14th century Spain. In 1478 Ferdinand and Isabella invited the Inquisition into Spain to search out and punish Jewish converts to Christianity whom they believed secretly continued their previous religious practices.

To persecute converts, Inquisitors and others formulated a racial theory – that conversos and Jews were suspect not because of their beliefs, but because of who they were racially… having ‘pure Christian blood’ became a requirement for noble status.

In 1492, shortly after the conquest of Granada, Isabella and Ferdinand issued an edict expelling all practicing Jews from Spain.

New Monarchies - England

Following the Hundred Years’ War, England entered the War of the Roses, a conflict between two factions, the House of York and the House of Lancaster. The Yorkists had the symbol of the white rose and the Lancastrians had a red rose.

Edward IV defeated the Lancasters and began to reconstruct the monarchy. Together with his brother Richard III and Henry VII, who was a Tudor, worked to crush and control the power of the nobility and used ruthless methods to consolidate power.

Henry VII did call several meetings of Parliament early in his reign, but most nobility were not trusted, and Henry used a council of small landowners as advisors. This council conducted foreign policy and secured the marriage of Henry VII’s oldest son, Arthur, to Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella.

This council had a judicial branch known as the Star Chamber, a royal system of courts outside of Parliament’s control. This court was counter to common-law, but reduced dissent.

Technology and Voyages of Discovery

Europeans were not isolated before the voyages of exploration, but because they didn’t produce many goods desired by Eastern traders, Europeans played only a small role in the Indian Ocean trading world.

European expansion had multiple causes:

Revival after the Black Death created demand for luxuries, especially spices, from the East.

Religious fervor was another important catalyst for expansion.

An eagerness to earn profit certainly stimulated the voyages of discovery.

Renaissance curiosity also served to push for the voyages of discovery among Europeans.

Voyages were made possible by the growth of government power and advances in technology.

Technological developments in shipbuilding, weaponry, and navigation also paved the way for European expansion.

The galley ship was replaced by the caravel.

Great strides in cartography – around 1410 Arab scholars re-introduced Europeans to Ptolemy’s Geography.

Other inventions such as the magnetic compass, the astrolabe, gunpowder, the sternpost rudder, and the lateen sail all helped to a more maneuverable ship and allow for better navigation.

The caravel could also be fitted with canon and because of its maneuverability could dominate larger vessels.

Under Prince Henry the Navigator, Portugal went from a poor nation to a rich and respected one.

Portugal’s conquest of Ceuta, an Arab city in northern Morocco (1415) marked the beginning of European overseas expansion.

The Portuguese settled the Atlantic islands of Madeira and the Azores before establishing trading posts along the gold-rich Guinea coast of western Africa.

Diaz and da Gama solidified Portugal’s place in exploration history.

Columbus is a controversial figure in history – glorified by some as a courageous explorer, vilified by others as a cruel exploiter of Native Americans.

Columbus was a deeply religious man who believed he had a responsibility to spread Christianity.

He landed in the Bahamas, which he christened San Salvador in 1492. He thought he had found some small islands off the east coast of Japan.

On Columbus’ second voyage he forcibly subjugated the island of Hispaniola and enslaved its indigenous peoples.

The Florentine navigator Amerigo Vespucci realized what Columbus had not. Writing on his discoveries off the coast of Venezuela he called the areas a “New World.” He described the area new continent which was later named for him – America.

Rivals on the World Stage

In Portugal, Prince Henry “the Navigator” supported early exploration of the African coast by supporting the study of navigation and geography by founding a school for seafarers.

The Portuguese motives for exploration included military glory, the conversion of Muslims, and a quest to obtain gold, slaves, and an overseas route to the spice markets of India.

In 1487, Bartholomew Diaz rounded the southern tip of Africa, but was forced turn back due to weather and a potential mutiny.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama made it around the Cape of Good Hope and reached India.

Spain established colonies across the Americas, Caribbean, and the Pacific, making it a dominate state in Europe in the 16th century.

After the voyages of Columbus, to settle competing claims in the Atlantic between Portugal and Spain, Pope Alexander VI negotiated the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. This gave everything west of an imaginary line to Spain and everything east to Portugal.

Hernando Cortez helped establish the Spanish presence in North America by conquering the Aztecs by using horses, cannons, and diplomacy.

Ferdinand Magellan, though Portuguese, sailed under the flag of Spain and successfully circumnavigated the earth by going through the Straits of Magellan, now named for him.

Francisco Pizarro claimed South America by conquering the Incas in 1521 after smallpox had devastated the Inca population.

After the dominance of the Spanish and Portuguese in the 16th century, the Atlantic nations of France, England, and The Netherlands would later compete by establishing their own colonies and trading networks.

France established trading factories in Canada, with Samuel de Champlain founding the first permanent French settlement in Quebec in 1608

England founded a colony in Roanoke in 1585, followed by Jamestown in 1607 and settlements in New England in 1620 and 1630.

The Dutch East India Company, established in 1602 challenged Portugal’s empire in the Indian Ocean. In 1621, the Dutch West India Company sought open trade with North and South America, challenging the Spanish.

1.8-1.10 Colombian Exchange, Slave Trade, Commercial Revolution

Colombian Exchange

The travel between the Old and New Worlds led to an exchange of plants, animals, and diseases known as the Columbian Exchange.

This exchange in some cases facilitated European subjugation and the destruction of indigenous peoples, particularly in the Americas. Smallpox, measles, and influenza ravaged native populations.

Europeans brought familiar crops with them and the exchange of foods was a great benefit to both cultures. Europeans returned with crops that would become central elements of European diets, such as the potato and maize. Europeans also brought with them domestic livestock, which allowed for faster travel and facilitated the transport of heavier loads.

Brought from Europe to the Americas

Wheat

Cattle

Horses

Pigs

Sheep

Smallpox

Brought to Europe from the Americas

Tomatoes

Potatoes

Squash

Corn

Tobacco

Turkeys

The Slave Trade

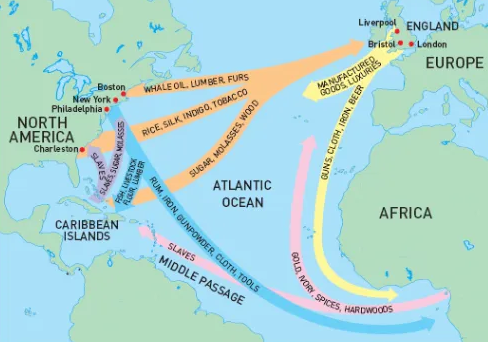

Europeans expanded the slave trade in response to a plantation economy in the Americas. Charles V authorized traders to bring enslaved Africans to the Americas in 1518.

The voyage to the Americas was known as the Middle Passage, and before 1700, about 20 percent of the slaves died due to dysentery from lack of sanitation and contaminated food and water. Slave traders packed hundreds of people onto ship in order to increase profits.

After Spain, the Portuguese, Dutch, and English all began the transport of slaves to the Americas. Most of these initially were to work in the sugar plantations, but by 1875, it is estimated that over 12 million enslaved Africans were brought to the Americas to work in the production of sugar, cotton, rum, tobacco, wheat, and corn.

Commericalizing Argiculture

The Open-Field System—the fields were open, and the land was divided into several strips with no hedges or fences. To prevent soil exhaustion, some of the fields were left fallow (either on a two- or three-year rotation) and crops were rotated.

Traditional Village Rights—open meadows were used for hay and animal pasture, poor women would glean grain, and the woodlands were held in common (for firewood, berries, and building materials).

Social Conditions—The state and landlords levied heavy taxes and high rents. The peasants were worst off in eastern Europe where some had to work many days on the lord’s land with no pay and somewhat better off in western Europe where serfs could own land and pass it on to their children.

Eliminating the Fallow—This meant alternating grain with nitrogen-restoring crops (peas, beans, turnips, potatoes, clovers, and grasses), which in turn meant better feed for animals, more fodder, hay, and root crops for the winter months, larger herds of cattle and sheep, more meat and better diets, more manure for fertilizer, and more grain for bread.

The Enclosure Movement—The agricultural innovators (experimental scientists, some governmental officials, and a few big landowners) fenced the individual shares of the common pastureland in order to farm more effectively, at the expense of poor peasants who relied on common fields for farming and pasture.

Old and New—Poor, rural people opposed enclosure since their survival was at stake. In some countries, they found allies in the nobility, since they were wary of the financial costs of purchasing and enclosing land. However, the new and old systems stood side by side as late as the nineteenth century in some parts of western Europe.

The Dutch were forced to take the lead in draining marshes since the Low Countries were one of the most densely populated regions in Europe and had a growing urban population.

Agricultural Innovation in England—Dutch experts helped drain the extensive fens (marshes) in rainy England. Jethro Tull (1674–1741) was an important English innovator who developed better farming methods (horses, drilling equipment) through empirical research. By 1870, English farmers were producing 300 percent more food than they had produced in 1700.

Market-Driven Estate Agriculture—A tiny minority of English and Scottish landowners held most of the land in England, relying on an even smaller number of landless laborers for their workforce. In no other European country did proletarianization (transformation of large numbers of small peasant farmers into landless rural wage earners) go so far.