Communication Midterm Study Guide

The U.S. Court System (Chapter 1)

The Three Branches of Government (Articles 1-3)

designed to prevent the concentration of power in any one branch and ensure that no single person or group could wield too much influence over the affairs of the state.

Legislative (makes laws)

It is split into two different chambers – the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress is a legislative body that holds the power to draft and pass legislation, borrow money for the nation (collect taxes), declare war, and raise a military. It also has the power to check and balance the other two federal branches.

Executive (carries out laws)

his branch of the government manages the day-to-day operations of government through various federal departments and agencies, such as the Department of Treasury. At the head of this branch is the nationally elected president of the United States. The executive branch powers include making treaties with other nations, appointing federal judges, department heads, and ambassadors, and determining how to best run the country and military operations.

Judicial (evaluates laws)

Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), U.S. Courts of Appeals,

and U.S. District Courts. Outlines the powers of the federal court system. The article states that the court of last resort is the U.S. Supreme Court, and that the U.S. Congress has the power to determine the size and scope of those courts below it. All judges are appointed for life unless they resign or are charged with bad behavior. Those facing charges are to be tried and judged by a jury of their peers.

The First Amendment

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances”.

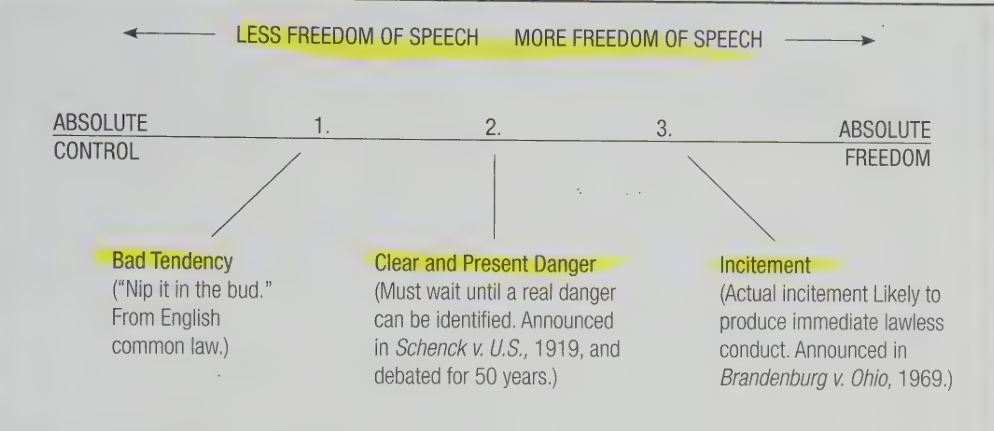

Freedom of Speech: The right to express ideas and information freely without government interference or censorship.

Freedom of Religion: The right to practice any religion or no religion at all, and protection from government establishing an official religion or favoring one religion over another.

Freedom of the Press: The right for media and journalists to publish news, information, and opinions without government restriction.

Freedom to Assemble: The right to gather peacefully for demonstrations, protests, and meetings.

Freedom to Petition the Government: The right to make complaints or seek assistance from the government without fear of punishment or reprisals.

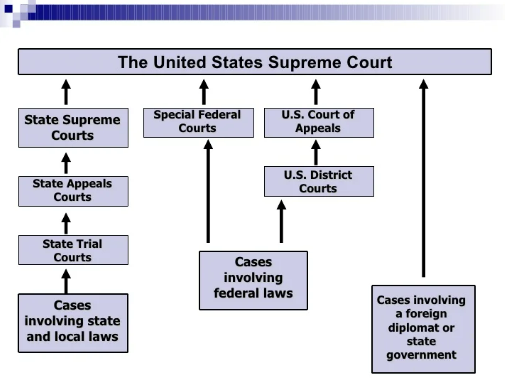

Federal and State Court

Federal Courts: (Jurisdiction over Federal Laws)

Jurisdiction: Federal courts hear cases involving federal laws, the U.S. Constitution, disputes between states, and cases involving different states' residents with more than $75,000 at stake.

Judges: Federal judges are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. They serve for life unless impeached.

Types of Cases: Examples include cases involving federal crimes, bankruptcy, patent law, and cases where the U.S. government is a party.

State Courts: (Jurisdiction over everything else)

Jurisdiction: State courts handle cases involving state laws and local disputes. They cover a broader range of cases, including most criminal, family, and personal injury cases.

Judges: State judges are either elected or appointed, and their terms and selection processes vary by state.

Types of Cases: Examples include traffic violations, family law matters (like divorce and child custody), contract disputes, and personal injury claims.

How the Court System Works

MAP:

Beginning of Suit

Bring Federal claim to a U.S. District Court

District Courts hear all the facts, hear witnesses, often have juries

One party wins the case

Appeal

Losing party can appeal the District Courts decision to the Court of Appeals (one of the 11 Circuit Courts) for that District

Appellate Courts argue only the law, no factual disputes

Ultimate Appeal

After the Appellate Court renders its decision, the losing court can appeal again to the U.S. Supreme Court

If the issue is very important and an issue of first impression (1), the U.S. Supreme Court may grant Certiorari (2) to hear the case

only listens to the legal argument, no facts, no witnesses, no juries

(1): An issue of first impression is a legal issue that has not been decided by the governing jurisdiction before. Such an issue cannot be resolved by relying on existing precedent or law and requires a new interpretation or application of the law.

(2): Certiorari is a legal term referring to a court process used to seek judicial review of a decision made by a lower court or government agency.

History of Free Speech (Chapter 2)

How Speech Was Controlled in Colonial America

There was total union between Church and State. Only certain powerful individuals, such as Clergymen and Royal Governors, could speak without fear of punishment. The elected colonial assemblies gained Freedom of speech for themselves but were hesitant to extend it to the people. The American Revolutionary War (War of Independence (1776)) was won and The Bill of Rights (1789) granted freedom of speech to everyone.

Main issues of speech in Colonial America:

Blasphemy

Blasphemous libel is a form of criminal libel that involves the publication of material that insults, offends, or vilifies a deity, Christ, or the Christian religion.

Historically, blasphemous libel was an offense under the common law of England and was adopted in British colonies and territories. It was used to protect religious sentiments and maintain social order.

Sedition

Seditious libel is a criminal offense involving the publication of material with the intent to bring contempt or disrepute upon political authorities. It includes statements that criticize or provoke dissatisfaction with the government3.

Historically, Seditious libel was a common law offense in England and was brought to North America by English colonists. It was used to suppress dissent and maintain political stability. Notably, the trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735 highlighted the conflict between colonial attitudes towards freedom of speech and the restrictive laws of seditious libel

Zenger case (1735) facts:

• Publisher of a political newspaper (John Peter Zenger) published a piece on Governor Cosby of New York’s policies—election rigging, bribery, favoritism, incompetence. Cosby seized the papers and charged Zenger with seditious libel

• Origins of truth as a defense

• Origins of idea that we should be able to speak about the conduct of government officials

What Groups Have Been Historically Most Affected by Limits on Free Speech

Immigrants/Foreign Nationals:

Legal Restrictions: Non-citizens have often faced restrictions on their speech, especially during times of political tension. For example, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 allowed the government to deport foreigners deemed dangerous and made it harder for new immigrants to vote.

First Amendment Rights: While non-citizens do have some First Amendment protections, these rights are not always as robust as those for citizens. For instance, non-citizens can be deported for speech that would be protected for citizens

Women (Rights in theory, not in practice):

Legal and Social Barriers: Historically, women faced significant legal and social barriers to free speech. They were often excluded from public discourse and decision-making processes. Women's voices were marginalized, and their opinions were frequently dismissed or undervalued.

Their speeches and writings were censored, and their public gatherings were often disrupted by opponents. Women persisted in their fight for equality, eventually leading to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which granted women the right to vote.

African Americans:

African Americans faced severe restrictions on their speech, particularly in the Jim Crow South. Laws and practices were designed to suppress Black voices and maintain racial segregation. For example, laws against "incitement to riot" were often used to silence civil rights activists. Additionally, African Americans who spoke out against racial injustice risked violent retaliation from white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

Intimidation tactics to restrain African Americans from education and speaking out

Slave Code (1830s)

Death penalty for any rebellion

No freedom of movement

No assembly

No weapons or modes of transport or music

No religion without chaperone

No education

Free blacks cannot intermingle with slaves

Labor Unions / Marxist / Communists:

The early labor movement in the United States was heavily influenced by Marxist ideas. Unions often faced violent repression, (ex. Haymarket Riot of 1886.)

During the Red Scare periods, individuals associated with communist or socialist ideologies were often targeted and silenced by the government

Non-Christians:

Christianity, particularly Protestantism, was often considered part of the "common law" in many American colonies and states. This meant that laws and legal principles were influenced by Christian doctrine, making it difficult for non-Christians to express their beliefs freely.

Blasphemy cases were common in state courts until the 20th century. These cases involved the prosecution of individuals for making statements that were considered offensive to Christian beliefs.

Example: In 1924, a person in Pennsylvania could be arrested for saying that the Bible was false. Such laws were intended to protect the dominant religious beliefs and maintain social order, often at the expense of religious minorities.

Legal and Social Persecution: Non-Christians faced legal and social persecution for their beliefs. Laws against blasphemy and heresy were used to silence religious dissent and maintain religious conformity.

Examples: Quakers faced severe penalties in Puritan Massachusetts, and Jewish communities often faced social discrimination and limited rights.

The Impact of the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798)

A series of four laws passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress during the presidency of John Adams. These laws were enacted amid fears of an impending war with France and were aimed at strengthening national security.

Made U.S. citizenship more difficult

Gave the President the right to expel any alien who was believed to be “dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States”

You could be arrested for any “false, scandalous, and malicious” writing against the government

Time, Place, and Manner Restrictions (TPM) (Chapter 11)

The Three Parts Where Government Can Prevent Speech

Content-Neutral: The regulation must be neutral regarding the content of the speech.

Narrowly Tailored: The regulation must serve a significant governmental interest.

Alternative Channels: The regulation must leave open ample alternative channels for communication.

The Three Kinds of Public Forums (Government Property)

Traditional Public Forums: Public spaces historically associated with free expression, such as parks and streets.

Designated Public Forums: Public spaces explicitly set aside by the government for expressive activities, such as meeting rooms or municipal auditoriums.

Limited Public Forums: Public spaces limited to certain groups or topics, where the government can enforce restrictions based on subject matter or speaker identity.

The Different Kinds of Private Property

Private Residences: Homes and personal property.

Private Businesses: Commercial properties owned by individuals or corporations.

Private Institutions: Non-governmental organizations, such as private schools or clubs.

How the TPM test was established Through Case Law

Davis v. Massachusetts (1897):

Facts: An ordinance in Boston prohibited public addresses on public grounds without a permit.

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld the ordinance, emphasizing the government's authority to regulate speech in public spaces to maintain order.

Hague v. CIO (1939):

Facts: Jersey City banned political meetings in public places.

Ruling: The Supreme Court ruled that streets and parks have historically been held in trust for public use, and the government cannot completely prohibit speech in these areas.

Schneider v. State (1939):

Facts: Municipal ordinances banned the distribution of handbills to prevent littering.

Ruling: The Supreme Court held that the purpose of keeping streets clean was insufficient to justify prohibiting the distribution of literature, emphasizing the importance of free speech.

Cox v. New Hampshire (1941):

Facts: A New Hampshire statute required a permit for parades and processions.

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld the statute, stating that regulations ensuring public order and safety are consistent with civil liberties.

Jamison v. Texas (1943):

Facts: A Dallas ordinance prohibited the distribution of handbills on the streets.

Ruling: The Supreme Court ruled that the ordinance violated the First Amendment, as it restricted religious activities and free speech.

Ward v. Rock Against Racism (1989):

Facts: New York City required performers in Central Park to use city-provided sound equipment to control noise levels.

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld the regulation, stating that it was a valid time, place, and manner restriction that was content-neutral and narrowly tailored to serve a significant government interest

The Difference Between Speech regulation in the Three types of Public Forums

Traditional Public Forums:

Examples: Streets, parks.

Regulation: Speech can be regulated based on time, place, and manner, but restrictions must be content-neutral, narrowly tailored, and leave open alternative channels for communication.

Designated Public Forums:

Examples: Public meeting rooms, municipal auditoriums.

Regulation: Similar to traditional public forums, but the government can limit access to certain groups or topics.

Limited Public Forums:

Examples: School facilities, government buildings.

Regulation: The government can impose restrictions based on subject matter or speaker identity, as long as they are reasonable and not an effort to suppress a particular viewpoint.

Different Kinds of Private Spaces:

Private Residences: Homes and personal property.

Private Businesses: Commercial properties owned by individuals or corporations.

Private Institutions: Non-governmental organizations, such as private schools or clubs.

The Idea of “Compatible Use”

The concept of "compatible use" refers to whether the manner of expression is compatible with the normal activity of a particular place at a particular time. For example, loud protests might not be compatible with a hospital zone, while they might be acceptable in a public park. The government can regulate speech to ensure it does not disrupt the primary use of the space.

Application!

Using the TPM Test:

Content Neutrality:

Determine if the law applies to all speech regardless of the message.

Example: A noise ordinance that applies to all loudspeakers, regardless of the content being broadcast.

Narrow Tailoring:

Check if the law serves a significant government interest (e.g., public safety, traffic control) and restricts no more speech than necessary.

Example: A law prohibiting loudspeakers in residential areas during nighttime hours to reduce noise pollution.

Alternative Channels:

Ensure the law allows for other means of communication.

Example: Prohibiting loudspeakers in certain areas but permitting leafleting or holding signs.

Applying the Test for Speech in Public Forums:

Traditional Public Forums:

Use the TPM test: The restriction must be content-neutral, narrowly tailored, and provide alternative channels.

Example: Restricting demonstrations in a park during peak hours to ensure public safety.

Designated Public Forums:

Apply the TPM test, recognizing the government's ability to limit access to certain groups or topics.

Example: A city auditorium reserved for community meetings, but not commercial events.

Limited Public Forums:

Ensure restrictions are reasonable and not an effort to suppress a particular viewpoint.

Example: A school gym available for educational activities but not political rallies.

Key Points to Remember:

For content neutrality, focus on whether the law targets speech based on its message.

For narrow tailoring, consider if the law is carefully designed to achieve a significant interest without being overly restrictive.

For alternative channels, ensure there are other ways for people to express themselves.

Political Speech / Incitement (Chapter 3)

The Provisions of the Espionage Act (1917, amended 1918)

Soon after the U.S. declared war against Germany in 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, primarily to prevent sabotage and communication of military secrets to the enemy. A person convicted of violating these provisions could be fined up to $10,000, imprisoned for up to 20 years, or both.

Provision on speech claimed

You can punish speech that had the INTENT to:

Interfere with operation of the military

Promote the success of the US’s enemies

Attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in armed forces or Interfere with the draft.

In 1918, the Espionage Act got amended

Congress says the Espionage Act isn’t strong enough! now it includes:

False reports re: military aims

Say/do anything to interfere with sale of bonds

Do anything to interfere with draft

Willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about: US, gov’t, military, constitution, flag, uniforms; or

Any language that will subject US to scorn or contempt

Provoke resistance to US

Promote enemies

Display enemy flags

Interfere with war time production of goods

Or teach, support any of the above

The Provisions of the Smith Act (1940)

Also known as the Alien Registration Act. Provides "the most drastic restrictions on Freedom of Speech ever enacted in the United States during peace”- Zacharian Chafee Jr.

The purpose of each of its five sections can be summarized as follows:

Section 1: Punished speech that tried to create disloyalty in military

Section 2: No advocacy/teaching for overthrow of the government. Made it illegal to organize any group to advocate, advise, or teach the overthrow of the government.

Section 3: Punished those conspiring to violate the act

Section 4: Allowed the seizure of any written material that violated the act. (A proper search warrant was required)

Section 5: Penalty provision, originally max fine of $10,000 and/or up to 10 years’ imprisonment. Later increase to max fine of $20,000 and/or up to 20 years in prison.

During the war, the Smith Act was used only TWICE, neither made it to the Supreme Court.

(And lower courts were still ruling under “bad tendency” (see Dennis v. United States). People were being punished for speech advocating ideas rather than advocating action)

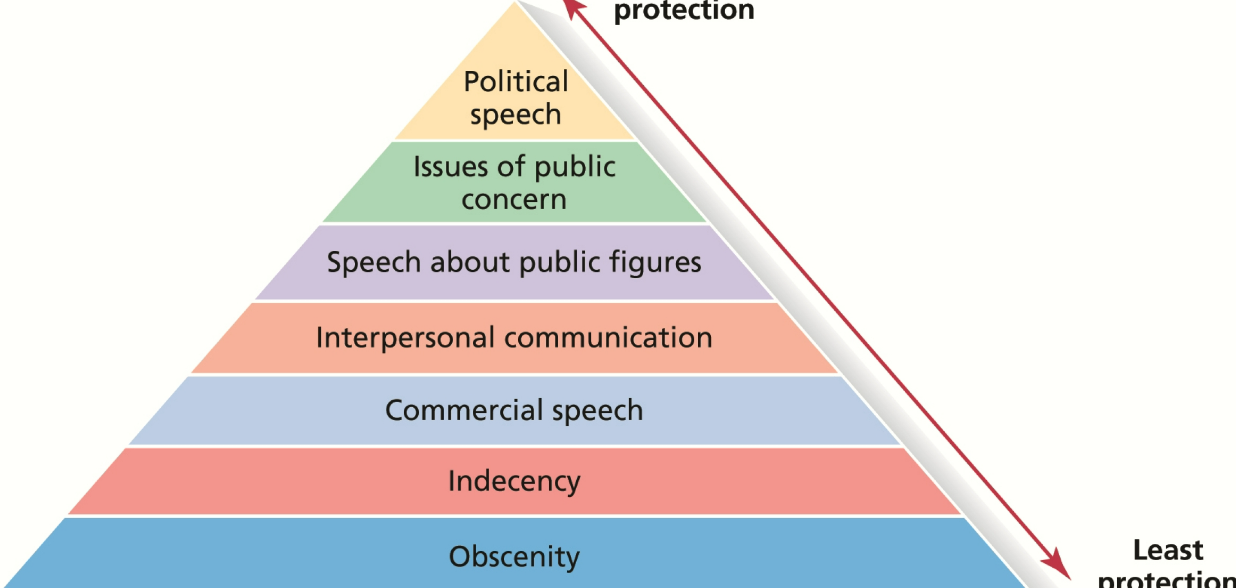

The Evolution of the Test of Acceptable Political Speech

Bad Tendency Test:

Early in the 20th century, courts used this test, allowing restrictions on speech that merely had a tendency to incite illegal activities, even if the danger was not imminent.

Clear and Present Danger Test:

Introduced in 1919, this test allowed restrictions on speech only if it posed a clear and present danger of causing significant harm.

Incitement to Imminent Lawless Action Test:

Established in 1969, this current standard restricts speech only if it is directed at inciting imminent lawless action and is likely to produce such action.

- Important Cases

Schenck v. United States (1919):

Facts: This is the first Supreme Court case to arise from

appealing an Espionage Act conviction. Charles Schenck distributed leaflets urging resistance to the draft during World War I.

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld Schenck's conviction, introducing the "clear and present danger" test. Justice Holmes stated that speech creating a clear and present danger, like shouting "fire" in a crowded theater, could not be protected.

Abrams v. United States (1919):

Facts: Jacob Abrams and others distributed leaflets criticizing U.S. involvement in Russia after WWI.

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld their convictions, applying the "clear and present danger" test. Justice Holmes, in dissent, argued for more protection of free speech unless it posed an imminent threat.

Opinion (Justice Clarke): People are “accountable for the effects which their

acts were likely to produce.” Even if they only meant to advocate for Russia,

they said things that could have the effect of harming U.S. military effort.

Convictions are upheld.

Dissent (Justices Holmes and Brandeis)

We should be using the “clear and present danger” test, and this speech did not pose an immediate danger

Marketplace of Ideas: “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

Holmes and Brandeis made additional dissents in other Espionage Act cases (like Gitlow v. New York), arguing for using the “clear and present danger” test instead of “bad tendency.”

Whitney v. California (1927):

Facts: Charlotte Whitney was convicted under California's Criminal Syndicalism Act for being a member of a group advocating violent overthrow of the government. She was a founder of the Communist Labor Party,

which was accused of promoting violent overthrow of government. Whitney claimed that violence was not the purpose of the organization

Ruling: The Supreme Court upheld her conviction using the "bad tendency" test. However, Justice Brandeis and Holmes, in a concurring opinion, emphasized the need for the "clear and present danger" standard.

There was no “clear and present danger!” We don’t really have the right to prevent speech just because it makes us a little afraid!

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969):

Facts: Clarence Brandenburg, a Ku Klux Klan leader, made a speech advocating violence at a rally.

Ruling: The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Brandenburg, establishing the "incitement to imminent lawless action" test. The Court held that speech could only be restricted if it was directed at inciting imminent lawless action and was likely to produce such action.

The Brandenburg rule establishes that in order to punish critical speech,

government must prove that the speech incites imminent lawless action. AND that it is likely to produce that action.

Even threatening speech is protected, said the Court, unless the state can prove that the “advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Application!

Brandenburg Rule:

Imminence: Determine if the speech is directed at inciting imminent lawless action. The key is the immediacy of the threat.

Likelihood: Assess whether the speech is likely to produce such lawless action. If there's no real likelihood of incitement, the speech is protected.

Example: If a speaker at a rally urges the audience to engage in violent acts immediately after the rally, and there's a real chance the audience might act on it, the speech could be restricted under the Brandenburg rule.

Distinguishing Speech Tests:

Bad Tendency: This older test allowed restrictions on speech if it had a tendency to lead to illegal activities, even if the danger was not immediate. This is a broad and less protective standard.

Example: Speech advocating for a political revolution, even if the threat is distant, could be restricted.

Clear and Present Danger: This test restricts speech only if it poses a clear and present danger of significant harm. It provides more protection than the "bad tendency" test by requiring a more immediate threat.

Example: During wartime, distributing leaflets that urge resistance to the draft could be restricted if it poses an immediate threat to military recruitment.

Incitement (Brandenburg): The current standard, this test restricts speech only if it is directed at inciting imminent lawless action and is likely to produce such action. It offers the highest protection for speech.

Example: Encouraging a crowd to commit a violent act immediately after a speech could be restricted.

Advice

Evaluate Context: Where and how is the speech delivered?

Assess Imminence and Likelihood: Apply the Brandenburg rule by evaluating the imminence of the threat and the likelihood of incitement. If both are present, the speech might be restricted.

Compare Standards: Use the "bad tendency" and "clear and present danger" tests to understand how older cases were decided and how the standards have evolved to provide more protection for free speech.

To understand the Brandenburg decision, one needs to consider the elements of intent and imminence in the test that was announced. First, expression must have a serious intent to incite illegal action. To be punishable, the speech in question must be more than “talking big” or “blowing off steam’—it must be seriously intended to incite unlawful conduct. Second, to be punishable, the “lawless action” urged must be imminent that is, immediate, impending, about to occur. In the words of the Court, speech may be punished if it is judged to be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and “likely to incite or produce such action.” This standard, which strongly protects the right to criticize the government, remains the Supreme Court’s operational test for “seditious” speech.

Defamation (Chapter 4)

Defamation refers to speech that “tends to lower a person’s reputation before others, cause that person to be shunned, or expose that person to hatred, contempt, or ridicule.”

The Two Types of Defamation

Libel (Written)

This refers to defamation that is written, printed, or otherwise published in a fixed medium, such as newspapers, books, online articles, or social media posts. Because it's in a permanent form, libel is generally considered more harmful and enduring.

Slander (Spoken)

This involves spoken defamation, typically occurring through speech, conversations, or broadcasts. Since it's not in a permanent form, slander is often seen as less damaging than libel, but it can still cause significant harm.

What a “Tort” is

A wrongful act (or an omission) that causes harm or loss to another person, leading to legal liability for the person who commits the act. Torts can result in physical injury, property damage, or harm to one's reputation, among other things. They differ from criminal law in that torts focus on providing compensation to the victim rather than punishing the wrongdoer.

In the case of defamation, a tort is a civil offense

The Difference Between Libel Per Se and Libel Per Quod

Libel per se (Obvious)

These are statements that are inherently defamatory and considered harmful on their face without the need for additional explanation. Examples include accusations of criminal behavior, having a contagious disease, professional incompetence, or engaging in immoral behavior. In libel per se cases, damages are typically presumed, and the plaintiff does not need to prove specific harm.

Libel per quod (Needs Proof)

these are statements that are not obviously defamatory on their face and require additional context or information to understand their defamatory nature. The plaintiff must provide evidence of the context that makes the statement defamatory and also prove that they suffered actual harm or damages as a result of the statement.

The Four Elements That a Plaintiff in a Libel Case must Prove

1. An insulting or harmful statement occurred.

2. That statement was published. This means it was communicated to a third party by voice, print, etc.

3. The subject of the statement must be identified. Not necessarily by name! But a normal person would be able to figure out who it is. (Singer of God is a Woman → Ariana Grande)

4. Fault must be proven (not always, depends upon the specific state law). For public figures: prove actual malice, meaning that this was a reckless, purposeful lie about the public figure. For private individuals: must show that whoever published these statements was negligent.

Potential Defenses Against a Libel Claim

1. I was telling the truth. You really are a filthy, sexually immoral criminal that has a bunch of gross diseases and you’re terrible at your job.

2. Your reputation was already so bad that nothing I can say is going to hurt it any worse.

3. What I published was privileged information! I had a right to say it! It came from someone in a trial or was said at a legislative session (absolute privilege). Or the subject matter is of significant public concern (qualified privilege) It was a journalist’s professional opinion (qualified privilege) or it was just in response to something you said about me! (self-defense; qualified privilege)

In the context of a libel claim, "privilege" refers to a legal defense that protects certain communications from being considered defamatory, even if the statements are false or damaging.

Absolute privilege: This provides complete protection against libel claims, regardless of the intent or knowledge of the speaker. It applies to specific situations, such as statements made during judicial proceedings, legislative debates, or other official government functions. The rationale is to allow open and honest communication without fear of litigation.

Qualified privilege: This provides protection in certain contexts, but it can be lost if the speaker acts with malice or abuses the privilege. Examples include fair and accurate reporting on public proceedings, employer references, or statements made to protect one's own interests. To maintain qualified privilege, the speaker must act in good faith and without intent to harm.

• To be protected, the speech can’t be malicious or intentionally harmful in nature.

• I can publish the arrest record and mugshot but can’t claim he’s guilty (until he’s either found guilty or admits guilt)!

• I can say that Star Wars sucked (“fair comment”), but I can’t claim that George Lucas sexually harassed Chewbacca.

• I could defame you if you defamed me, but only if what I said about you is a direct response to what you said about me.

The Differences in Defamation Protection

Public Officials

People who have some responsibility in government affairs (includes candidates for public office)

If they want to prove they’ve been defamed, must prove actual malice.

Public Figures

High profile people that have “persuasive power” in society.

What would be an example of a public figure?

There are “all purpose” and “limited” public figures.

Must prove actual malice for these folks, too.

Private Individuals

It’s not as easy for private citizens to defend themselves!

How Journalists Can Protect Themselves from Committing Libel

How actual malice works in practice

We just want to prevent a reckless disregard for what’s true

If you (the journalist) believe it’s true, then you didn’t have actual malice toward the person!

The more time you have to research a story, the more accurate you’re expected to be. Courts are more forgiving if false statements are published on a tight deadline.

You know when you hear the words “allegedly” or “reportedly?” This is a good way to cover your back!

Two Important Defamation Cases

New York Times v. Sullivan

Facts: “Heed Their Rising Voices” ad published in the paper. Discussed actions taken by the police toward protestors (and MLK, Jr.) that were untrue. At no point was Sullivan identified by name.

Opinion (Justice Brennan)

Public figures have to take “vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks” most of the time.

“The rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions...leads to comparable “self-censorship.”

Introduces the actual malice standard: Public officials cannot collect damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to their official conduct unless they can prove the statement was made with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.

Gertz v. Welch

Facts: Gertz was hired as an attorney to represent a family whose son was killed by a Chicago cop. The magazine American Opinion published an article calling Gertz a criminal and a Communist.

• Opinion (Justice Powell)

Private citizens like Gertz need more protection from defamation than public officials or public figures. Gertz was dealing with a high-profile lawsuit, but he’s still a private citizen.

Also, media defendants in libel cases should get more protection against libel actions so as not to censor them.

Effectively, this ruling creates a new set of laws regarding defamation, depending not just on who may have been defamed, but what kind of person/organization published the alleged defamatory statements.

How Much “Fault” needs to be proven?

Private v. Private

Just the basic elements: Defamation, publication, and identification

You can receive money damages without proving fault

If plaintiff can prove Actual Malice, you can win even more money (punitive damages)!

Private v. Media Defendant

Basic elements PLUS at least Negligence

Negligence: failure to do something a reasonable person would have done or not done

This protects media defendants a little more.

Also, plaintiff needs to prove the statements were false.

If plaintiff can prove Actual Malice, you can win even more money (punitive damages)!

Public Figures v. Anyone

• Basic elements PLUS Actual Malice

Knowingly telling a falsehood OR with a reckless disregard for the truth.

Types of Damages

Actual Damages: Compensation for real, quantifiable losses such as lost income, medical expenses, or damage to reputation.

Punitive Damages: Additional compensation meant to punish the defendant for particularly harmful behavior and deter future misconduct.

Presumed Damages: Compensation awarded without the need for proof of actual harm, often in cases of libel per se.

Actual Malice

Actual malice is a legal requirement in United States defamation law that applies to public officials or public figures when they file suit for libel. It refers to a statement made with knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for truth

Application!

Actual Malice:

Public Figures and Public Officials: The "actual malice" standard applies when the plaintiff is a public figure (e.g., celebrities, politicians) or a public official (e.g., government employees). They must prove that the defendant made the defamatory statement with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard for the truth.

Application: This higher standard protects free speech, especially in matters of public concern, by requiring the plaintiff to show that the defendant acted with intent to harm.

Example: A politician sues a news outlet for publishing a false story about them. To win, the politician must prove that the news outlet knew the story was false or acted with reckless disregard for its truth.

Negligence:

Private Individuals: The "negligence" standard applies when the plaintiff is a private individual. They must prove that the defendant failed to exercise reasonable care in verifying the truth of the defamatory statement.

Application: This lower standard acknowledges that private individuals have less access to public platforms to counteract false statements and, therefore, need more protection.

Example: A local business owner sues a blogger for posting a false review that harms their business. The business owner only needs to prove that the blogger was negligent in verifying the accuracy of the review.

Key Points: Public Figures/Public Officials: Apply "actual malice."

Private Individuals: Apply "negligence."

A media defendant is someone who is sued for publishing information that is a matter of public concern. In such cases, the burden is on the plaintiff to establish the falsity of the information

Privacy (Chapter 5)

What the Four Primary Privacy Torts Specify

Intrusion on Seclusion

This occurs when someone intentionally intrudes upon another person's private affairs in a manner that would be highly offensive to a reasonable person. Examples include secretly recording someone in a private place or eavesdropping on private conversations.

Disclosure of a Private Matter

This tort involves publicly disclosing private facts about someone, which would be highly offensive to a reasonable person and are not of legitimate public concern. For instance, sharing someone's medical history without their consent could fall under this category.

False Light

This happens when someone publishes information about a person that is misleading or false and portrays them in a highly offensive manner. The key difference from defamation is that the false light claim focuses on the misleading impression created, rather than just the falsehood of the statements.

Appropriation

This occurs when someone uses another person's name, likeness, or identity for their own benefit without permission. This is often seen in cases where a person's image is used in advertising or commercial purposes without their consent. Generally, newsworthy events or coverage of

political figures does not apply here.

How a Plaintiff can Prove Someone Committed Torts Against Them

Intrusion on Seclusion

We have a right to not have our private space invaded.

I think someone has done this to me! I need to prove:

That an intrusion occurred

That the intrusion happened in a place where I can reasonably expect privacy

A reasonable person would find this intrusion highly offensive

That means if it happened in public, it’s fair game!

Disclosure of a Private Matter

I think someone did this to me! I need to prove:

That the defendant publicized the private matter to the world at large (not just a couple of people)

That the publication of this matter would be highly offensive to a reasonable person

The things that were publicized were private and not newsworthy

That means if it’s a legitimate news concern, it’s ok to publish it!

False Light

I think someone did this to me! I need to prove:

That the false statement was widely distributed

That the false light would be highly offensive to a reasonable person

The action was done with malice

Sound like defamation? It’s close (but you don’t have to prove your

reputation was harmed)

Appropriation

To prove appropriation, a plaintiff must show:

(1) their name, likeness, or identity was used by the defendant

(2) for the defendant's benefit, typically commercial gain

(3) without the plaintiff's consent

(4) causing harm, whether financial or emotional.

If these elements are met, the plaintiff has a strong case.

Defense Media Companies Might Use

There are three primary defenses if a media company or individual is accused of violating a privacy tort

1. Consent: You already consented to have this material published (maybe a sign at the door)

2. Newsworthiness/public interest: This is important information for people to know about!

3. The Constitution: False light communication can be protected by First Amendment if the matter is of public concern. Plaintiff must prove actual malice. First Amendment protects publishing information that’s already in public records.

Difference between “False Light” and Defamation

False Light: This focuses on presenting someone in a misleading or false way that would be highly offensive to a reasonable person. It doesn't necessarily have to be a false statement; it could be a true statement presented in a misleading context. The harm is to the individual's personal feelings and emotional well-being.

ex: A magazine publishes a photograph of a person standing near a crime scene with the headline, "Local Resident Involved in Major Crime." Even though the person had no involvement in the crime, the photo and headline together create a misleading and offensive impression of their involvement.

Defamation: This involves making a false statement of fact about someone that injures their reputation. Defamation can be either written (libel) or spoken (slander). The harm is to the person's reputation and how they are perceived by others.

ex: A blogger writes a post falsely claiming that a local business owner has been embezzling funds from their company. This false statement damages the business owner's reputation and leads to a loss of customers.

How and Why Plaintiffs sue for “Intentional Infliction of Emotion Distress”

For public officials and public figures, it’s hard to win privacy cases.

Media companies can be protected by arguing newsworthiness

In the case of false light accusations, actual malice must be proved. So, public figures have tried to protect their privacy by suing under a different tort called intentional infliction of emotional distress

This tort is intended to protect against deliberate expressions/conduct that are so

outrageous that they cause extreme emotional distress.

Important Privacy Cases

Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1983)

This case involved a parody ad published by Hustler Magazine that depicted Reverend Jerry Falwell in an offensive manner. Falwell sued for libel, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Hustler Magazine, stating that public figures cannot recover damages for emotional distress without proving that the publication contained a false statement made with actual malic

OPINION OF THE COURT (Chief Justice Rehnquist)

“Public figures as well as public officials will be subject to ‘vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks’”

Even speech that’s motivated by “hatred or ill will” is protected by the First Amendment

RULE(S) ESTABLISHED

Parodies are a protected form of political speech

To win an IIED case, a public figure (or official) must prove that extreme emotional distress was caused by a deliberate falsehood, and the defendant had actual malice

Snyder v. Phelps (2011)

This case involved the Westboro Baptist Church picketing at the funeral of Marine Lance Corporal Matthew Snyder. The picketers held signs with offensive messages, causing emotional distress to Snyder's father. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the church, stating that their speech was protected under the First Amendment because it addressed matters of public concern and was conducted in a public place

The First Amendment protects the right of protest or criticism in public spaces, even if it may cause emotional distress.

Application!

Identify the Tort:

Intrusion on Seclusion: Invasion of someone's private space.

Disclosure of a Private Matter: Publicly sharing private information.

False Light: Misleading and offensive portrayal.

Appropriation: Using someone's identity without permission for gain.

Apply Relevant Standards:

Newsworthiness Defense: Information of legitimate public concern can be a defense.

Actual Malice: Public figures must prove the defendant knew the information was false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth; private individuals must prove negligence.

Example Scenario:

Imagine a celebrity is photographed at a private event and the photo is published with a misleading caption implying they were involved in illegal activities. Here’s how you might apply the standards:

Identify the Tort: This could be a case of false light since the caption creates a misleading and offensive impression.

Newsworthiness Defense: The defendant might argue that the photo is newsworthy since the celebrity's activities are of public interest.

Actual Malice: As the celebrity is a public figure, they would need to prove that the publisher acted with actual malice, either knowing the caption was false or acting with reckless disregard for its truth.