Critical Thinking in Helping Professions

~Learner Goals~

Identify, recognize, and apply strategies that comprise critical thinking.

Recognize and describe factors that form flawed beliefs and lead to poor choices.

Describe the personal characteristics of a critical thinker.

Recognize the relationship between critical thinking and clinical practice.

What is Critical Thinking?

ask questions and don’t make assumptions

Misconceptions: critical thinking is NOT argumentative, opposing, or destructive. Not tearing other people’s ideas down.

Critical Thinking: the ability and willingness to assess claims and make objective judgments on the basis of well-supported reasons and evidence rather than emotion or anecdote (Wade, Tavris, and Garry, 2014).

Critical thinkers are able to look for flaws in arguments and to resist claims that have no support.

Criticizing an argument is not the same as criticizing a person making it, and they are willing to engage in vigorous debate about the validity of an idea.

Critical thinking is not merely negative thinking. Needing more information is not negative, questioning things is not negative.

It includes the ability to be creative and constructive the ability to come up with alternative explanations for events think of implications of research findings and apply new knowledge to social and personal problems.

Claim(s): a belief, a statement that something is true or a fact

In other words, a claim is related to something you are being asked to believe or do or you are asking others to believe or do

Hold weight on what to believe then what to do

Objective: without bias, (of a person or their judgment) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts.

In other words, something that can be verified. Example - I can see it, and you can see it, too

Subjective: based on or influenced by personal feelings, tastes, or opinions

Something that can’t easily be verified. Example - I can see it or sense it, but you can’t

Emotion is a subjective experience.

In sum, the definition encourages us to examine statements that we are being asked to believe or do based on info that can be verified vs. info that cannot.

Anecdote: (story) short account of an amusing, interesting, or telling incident or experience; sometimes with implications of superficiality or unreliability.

In other words, something that is easily understood and appealing but not necessarily accurate.

Example: let me tell you what happened…

In sum, the definition encourages us to be cautious when presented with reasons based on a “good” story.

Emotion: a strong instinctive feeling deriving from one’s circumstances, mood, or relationships with others.

“Affect” - refers to positive or negative feelings including:

Emotion = in-the-moment, relatively brief, automatic response.

Mood = diffuse feeling lingering over time.

Attitude = Established feelings about someone or something.

Question: is affect/emotion present in helping relationships?

Emotion:

The client produces an accurate /r/ sound during treatment: Happy positive feeling

Your client does not produce accurate /r/ sound: Less positive maybe disappointed feeling

Mood:

Your client completed 4 weeks of treatment: Be in a great mood

Your client wasn’t successful after 4 weeks of treatment: Not in a great mood

Attitude:

Clinic that is a good place to work: have a good feeling

Clinic that is not a fun place to work: Have dread going to work

For a variety of reasons, helping relationships rarely occur in emotionally neutral situations.

Thus, critical thinkers need to understand how emotion may play a role in their ability to interpret, evaluate, and make decisions, especially in a helping relationship.

Often times feelings are telling you valuable information as well.

Compassion: feelings of compassion and desire to help others are emotions that typically underlie most peoples’ reasons for choosing helping professions as a career.

Emotions can be helpful because they correspond with real-world events.

Beliefs and evaluations that support emotions often correspond to actual events in the world.

Emotions can also hinder us because they sometimes cloud our judgment or skew our perception of a situation.

And bias our evaluation in ways that might be incorrect.

In other words, critical thinkers appreciate emotions may help or hinder decision-making.

Thus, it is essential they develop emotional competence: (emotional competence)

Emotional competence:

(1) Being aware of emotion and what triggered it

(2) Recognizing and understanding other’s emotions

(3) Using compassion to form relationships with others

(4) Understanding how emotions may be influencing one’s thinking

Compassion vs Empathy: I acknowledge your situation and see your hurting here is how I can help. Not getting dragged down to feeling how they feel.

In sum critical think in a helping relationship is not “bloodless, solemn, or dispassionate,” (Wade, 1995).

Rather it is understood that emotion may help or hinder thinking and should be evaluated when necessary

Perhaps, the definition of critical thinking is telling us: (1) be careful not to let emotions hinder our decision-making or to rely on unverifiable information (2) Or let others persuade us to believe or do something based on emotional reasons alone

In sum, our view of critical thinking includes: evaluating what others are asking us to believe or do, making decisions based on good reasons, especially when helping others, appreciating that helping relationships often involve feelings, such as compassion, and desire to make the best possible choices for people who need our help.

Why is Critical Thinking Relevant in Helping Professions?

In the future, I will need to manage and evaluate an expanding and evolving body of complex information that will come at me from different directions and sources.

Some of that information will come from sources that are trustworthy and some from sources that should be carefully judged for credibility

And critical thinking will help you evaluate the trustworthiness of these sources and the quality of that information

Because research shows smart, good-intentioned people make foolish decisions and hold false beliefs

Including physicians, psychologists, Wall Street investors, and scientists

Example 1: A common “false belief” held by physicians and non-physicians was that we use only 10% of our brains — WRONG! Speech production, for example, is essentially a “whole” brain/nervous system activity.

Example 2: Even our professionals have held “false beliefs” about the best treatment choices such as: facilitated communication and nonspeech oral motor exercises

Critical thinking has been shown to minimize the likelihood of developing false beliefs and making poor choices.

Because most future employers want you to have critical thinking skills.

Because the accuracy of your beliefs and your decision-making skills are central to the quality of the choices you make for helping others in clinical practice.

Evidence-based practice (EBP): client perspectives, clinical expertise, and evidence (external and internal).

And when we make decisions to help others, we would like our beliefs to be based on clinical reality.

Critical thinking helps to increase the likelihood that clinical beliefs are as accurate as possible

More accurate clinical beliefs increase the likelihood our decisions to help will lead to the desired outcome for our clients

Because the belief that critical thinking will emerge naturally from higher education is based more on wishful thinking than actual evidence.

More likely to learn critical thinking when:

Taught directly as a set of skills and values

Practiced within the specific knowledge area

Critical thinking is recommended as a general knowledge and skill for undergraduate education in CSD by ASHA.

Critical thinking is valued by UGA as an outcome of your university education, as identified by the comprehensive learner record.

In sum, critical thinking is important to you because it is:

essential part of higher education

Relevant to becoming a SLP or AuD

A skill emphasized by employers

Essential for increasing chances of making best choices for people you want to help

Reducing chances you will unintentionally make poor choices

Chapter 1

Question 1:

Experts, to what degree do we trust them? They sound like they know a lot, sound confident and certain, and may disagree with each other, but at the same time, it is important to listen and then make up your own mind.

Listen to the other points of view because there may be something valuable there.

Experts know a lot and have relevant experience on a particular topic

Thus, listening to their views on that topic is worthwhile, especially when they provide supporting evidence.

Their expertise rarely applies outside their topic area.

Question 2:

Weak-sense thinker: critical thinking for selfish ends, defending own beliefs while tearing down other’s in order to promote their own views

Strong-sense: Critical thinking to evaluate all claims including one’s own, protect against self-deception and conformity, and open to other’s views when well-founded.

Strong-sense characteristics are:

more likely to protect against developing false beliefs

Thus making better choices for people seeking their help

weak-sense thinkers are more likely to be concerned about themselves than others

Question 3:

Values are:

ideas we view as worthwhile, but not always stated and provide the basis for evaluating the behavior of others and ourselves.

Question 4:

Based on ASHA Code of Ethics — Based on 4 principles:

Responsible for the welfare of your clients

Evaluate the effectiveness of your services

Protect confidentiality and security of your client’s records

Do not discriminate in service delivery on basis of race, gender, sexual, orientation, national origin, or religion.

Maintain your professional competence

Act with honesty and integrity

Uphold dignity and autonomy of our professions

Chapter 13

Question 1:

Obstacles to thinking

Knowing they are there, doesn’t mean they disappear

But can handle them if you slow down

Question 2:

Daul-Process Theory describes system 1 and system 2 thinking in more detail.

System 1 thinking - sometimes referred to as intuition - consists of habits, overlearned associations, and pattern recognition based on prior experience

Characteristics include: fast, no effort, no focus required, nondeliberate, working memory (what you have in your mind in the moment as your thinking things through) unnecessary, and may include automatic feelings such as “feeling of rightness” (i.e., “this feels right to me”)

System 2 thinking - it is conscious and self-regulated.

Characteristics include: slow, effortful, focused, deliberate, working memory necessary, and may include conscious feelings, such as “unpleasantness” (i.e., “thinking is hard!”)

System 2 is more likely to be required for critical thinking.

Systems 1 and 2 often interact with each other. System 1 throws out some answers, and then system 2 intervenes.

Question 3:

Why am I thinking what I’m thinking?

Question 4:

Why are stereotypes bad?

Broad characterizations about a person based on group membership

Efficient mental shortcuts, but can be unfair

This is an example of system 1 or 2

Question 5:

What stereotypes does the public have about communication disorders?

Question 6:

The halo effect — see someone with bias that they might be better than they are

Overgeneralize from one personal characteristic — positive or negative — to entire person

This is system one thinking

Question 7:

“When we change our minds in light of superior argument, we deserve to be proud that we have resisted the temptation to remain true to long-held beliefs. Such a change of mind deserves to be seen as reflecting a rare strength.” - Francis Bacon

Possibly most challenging bias for critical thinkers to overcome

This is sometimes referred to as “Myside Bias” (this is what I believe, it must be true)

Question 8:

The curse of knowledge: forget what it was like when we did not know what we now know

What you know now about anatomy of speech, and hearing is much more sophisticated than most people, including your future clients and sometimes we forget that they don’t know this like we do

Question 9:

Wishful thinking — optimism

We interpret information according to what we want to believe rather than what it really means esp. because what we want to believe makes us feel good and what it really means probably won’t

Result: we may mistakenly believe one thing when the reality is something else

System 1

Question 10:

The outcomes we “wish” for when we make our treatment decisions may be based on what we want to believe will happen rather than what the evidence suggests will happen

Caution wish & hope are not the same

hope implies a desired outcome that is possible or likely

Example: our hope that this client will improve is informed by plausible reasons (this treatment usually works)

Wish implies a desired outcome that is impossible or unlikely

Example: your wish that this client will improve is informed by unrealistic reasons ( this treatment rarely works but it will make me feel good if it does)

In sum, B & K are asking us to appreciate that:

System 1 or fast thinking works well, especially when we have lots of prior experience; but may mislead as suggested by speed bumps: stereotypes and halo effect

System 2 or slow thinking, especially when it includes critical thinking, may help us manage those speed bumps

However even critical thinkers may find challenges overcoming:

Belief perseverance because it requires us to accept that sometimes we may be wrong

Wishful thinking because it requires us to accept that our desires may not always match reality.

Chapter 2

Question 1:

Issue: question or controversy under consideration

In other words, an event that requires system 2 thinking and doesn’t have a ready answer such as a problem that needs to be solved, and ideally will encourage you to think critically

Question 2:

Descriptive: Questions about the accuracy of information

In other words, questions related to the credibility of facts that are relevant to CSD

Question 3:

Examples of descriptive issues - GLP

What type of communication disorder does a client have

What treatment approach is the most effective for managing this communication disorder

Question 4:

Prescriptive issue: (Good or bad, right or wrong) questions about how we should behave or act

In other words, questions related to standards of conduct or ethics concerning CSD professionals.

What should we do about clinicians who charge for services they never administered?

What should clinicians do when their client is unjustly denied services?

Question 5:

Conclusion: what an author wants you to believe or wants you to do

Who is an “author”? Authors of book, magazine, web page, podcast, blog, journal article. Also someone on social media or television. Peopel in your life, significant others, etc. Fellow helping professionals. And you! — when you make a claim

In other words, anyone who makes a claim

Question 6:

In sum B & K are asking us to appreciate that when beginning to evaluate an argument or claim, make sure you understand the:

Question or controversy under consideration = issue and what you are being asked to believe or do based on that issue = conclusion

Chapter 3

Question 1:

The basis for believing or supporting a conclusion

Question 2:

Essential for evaluating the credibility of the conclusion and encourages openness to other views

Question 3:

Argument = conclusion + reasons

Unfortunately B & K left out the “issue”

Issue & Conclusion + Reasons

In sum, B & K want us to understand that reasons are essential for evaluating an argument because they are meant to support the conclusion and provide a basis for determining the accuracy or credibility of the conclusion

Reasons will likely influence whether or not we will accept the conclusion

Where did those reasons come from will be important for us to “think” about later

What does “bias” mean?

Tendency to believe that some people, ideas, etc., are better than others that usually results in treating some people unfairly (doens’t matter for this class)

Strong interest in something or ability to do something (little more associated)

Quality that makes something likely to happen or that makes someone likely to think or behave in a particular way (this is definition we will use in this class)

For our purposes, “bias” is similar to an affective attitude — positive or negative feelings about someone or something that will influence how you think or behave.

In sum, “bias” can have negative connotations or meaning but not always.

Chapter 4

What words or phrases are ambiguous?

Question 1:

Do you understand the meaning of keywords/phrases?

if not, then you may not understand the argument

Because keywords/phrases will probably influence if you will accept a conclusion

Most likely find them in reasons or conclusions

Question 2:

Examples

Question 3:

Stuttering vs. Disfluency

Deaf vs. Hearing Impairment/Hard of Hearing

Speech vs. Language

Question 4:

Assume you and author share same meaning

ask: what do you mean?

Assume one definition only for term

ask: does word have other possible meanings?

In sum, B & K are asking us to appreciate that not everyone shares same meaning of words or phrases, thus when you can, it is important to doublecheck author’s intended meaning

For helping professionals, this is important because our understanding of CSD words may not be the same as the general public’s

Chapter 5

Question 1:

What assumptions needed for reasons to support conclusion.

Example: Clinician providing these reasons is honest

What assumptions needed for reasons to be true

Example: This language assessment provides accurate information as a reason for this diagnosis

Question 2:

Value assumption: an implicit preference for one value over another in a particular context

Keep in mind that a value is a principle or standard of behavior relevant for believing a claim

Example: An honest clinician’s claim is likely more believable than a dishonest clinician’s.

Question 3:

Background = a person’s education, experience, and social circumstances (Oxford English Dictionary).

The author’s background will likely say something about their values

But be careful because group membership doesn’t always mean a person shares those group values, although odds are they share some or most of them

Context does matter

Question 4:

ASHA Code of Ethics — Based on 4 Principles (abridged)

Responsible for the welfare of your clients

Maintain your professional competence

Act with honesty and integrity

Uphold dignity and autonomy of our professions

Question 5:

Their standards of conduct or professional values will be consistent and not in conflict, with the ASHA code of Ethics in the context of a helping relationship

Question 6:

Conflict of interest: situations where clinicians or researchers have conflicting interests or obligations that may influence their objectivity

Focus: Does a clinician or researcher have a conflict of interest?

Conflict arises when one role — being a clinician or researcher — is overly influenced by one of their other roles — e.g., financial or personal (Kazdin, 2015)

Why is conflict of interest a potential value conflict:

because we worry that financial or personal gain may negatively influence a practitiione’s clinical objectivity or a researcher’s scientific objectivity

and this might impact the credibility of their claim

Question 7:

How do we know if a clinician has a conflict of interest:

We probably won’t know unless they tells us or something about their background or behavior suggests it

Fortunately, conflict of interest is taken so seriously that clinicians are required to disclose if they have outside, related business or financial interests, influencing their decisions, such as:

Personal partnerships with businesses whose products they might suggest their clients purchase

Examples: Hearing aids and AAC Devices

AI — trying to train AI if a child miss pronounces a sound, but they are developing products that will be marketable

Must disclose possible conflicts of interest - ASHA

Ethically required to tell us

Researchers are also required to disclose if they have a conflict of interest in:

Published journal articles

Conference/webinar presentations

You shouldn’t have to guess about conflicts of interest

Thus, our focus when we look for value assumptions will be on conflict of interest, and this means:

If a clinician or researcher:

Openly discloses a conflict of interest or openly discloses no conflict of interest then we can evaluate the credibility of their reasons in view of that information.

What does each type of disclosure suggest to us:

IF they declare a conflict of interest, then we know their claim may be biased in favor of personal gain, but we appreciate that they told us.

IF they declare no conflict of interest, then we know their claim is less likely biased in favor of personal gain.

IF they declare no conflict of interest, and there actually is one and we find out then we strongly suspect their claim is biased in favor of personal gain.

Question 8:

Descriptive assumptions: unstated belief about way world is was or will be, ones beliefs about factual information

Question 9:

Need to know what information logically connects the reasons to the conclusion

Question 10 (a):

Our answers

Question 10 (b):

Our answers

Dissecting Research

Results: the researcher’s reasons

Discussion: how these results may support the conclusion

Method: how results were obtained where we look for their reasons

Finding descriptive assumptions:

Results from diagnostic assessments are the clinician’s reasons for concluding what a person’s problem may be

Quantity and quality of research evidence on managing communication disorder will likely influence the clinician’s reasons for selecting a treatment

look at the the methods or clinical procedures section

Disclosure statement in published research:

For ASHA: found at the bottom of first page of article in print form.

Authors info and affiliations

Likely at the end of the discussion before the references

Descriptive Assumptions:

When researchers provides reasons for supporting their conclusions, we need to look at how those reasons were obtained

Like most research studies: results section of a study provides the researches’ reasons

Discussion: section of a study describes how these results may support the researchs’ conclusion

We need to ask: How were the results obtained so we can determine if they are credible support for the conclusion

Method section of a study describes how the results were obtained so this is where we look for heir descriptive assumptions

When clinicians provides reasons for supporting their conclusions we need to look at how those reasons were obtained

Like most clinical situations results from diagnostic assessments are the clinician’s reasons for concluding what a person’s problem may be

and quantity and quality of research evidence on managing a communication disorder will likely influence the clinician’s reasons for selecting a treatment

We need to ask: how good are the assessments for arriving at a diagnosis

And how convincing is the research evidence for selecting a treatment.

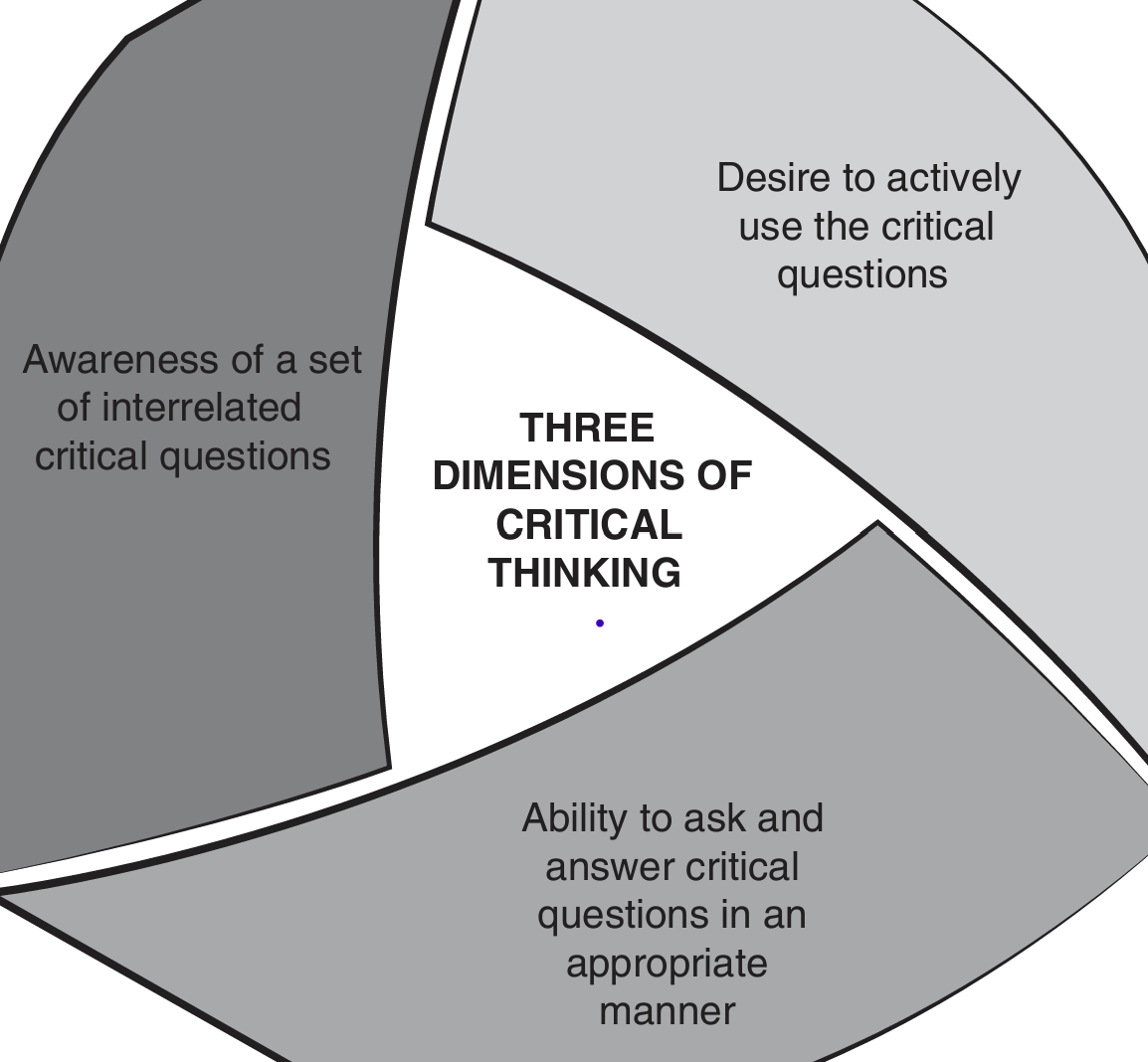

Critical thinking essential components:

Thinking skills (asking the right questions): Interpretation, evaluation, and metacognition

Thinking dispositions (Epistemic values):

Epistemic = related to what you know and reasons you believe you know it

Open-mindedness: wiling to consider alternative views, especially when supported by good reasons

Reflective thinking: willing to learn from past experiences and consider the quality of evidence

Knowledge of cognitive biases (Speed bumps):

Ways our thinking sometimes goes wrong

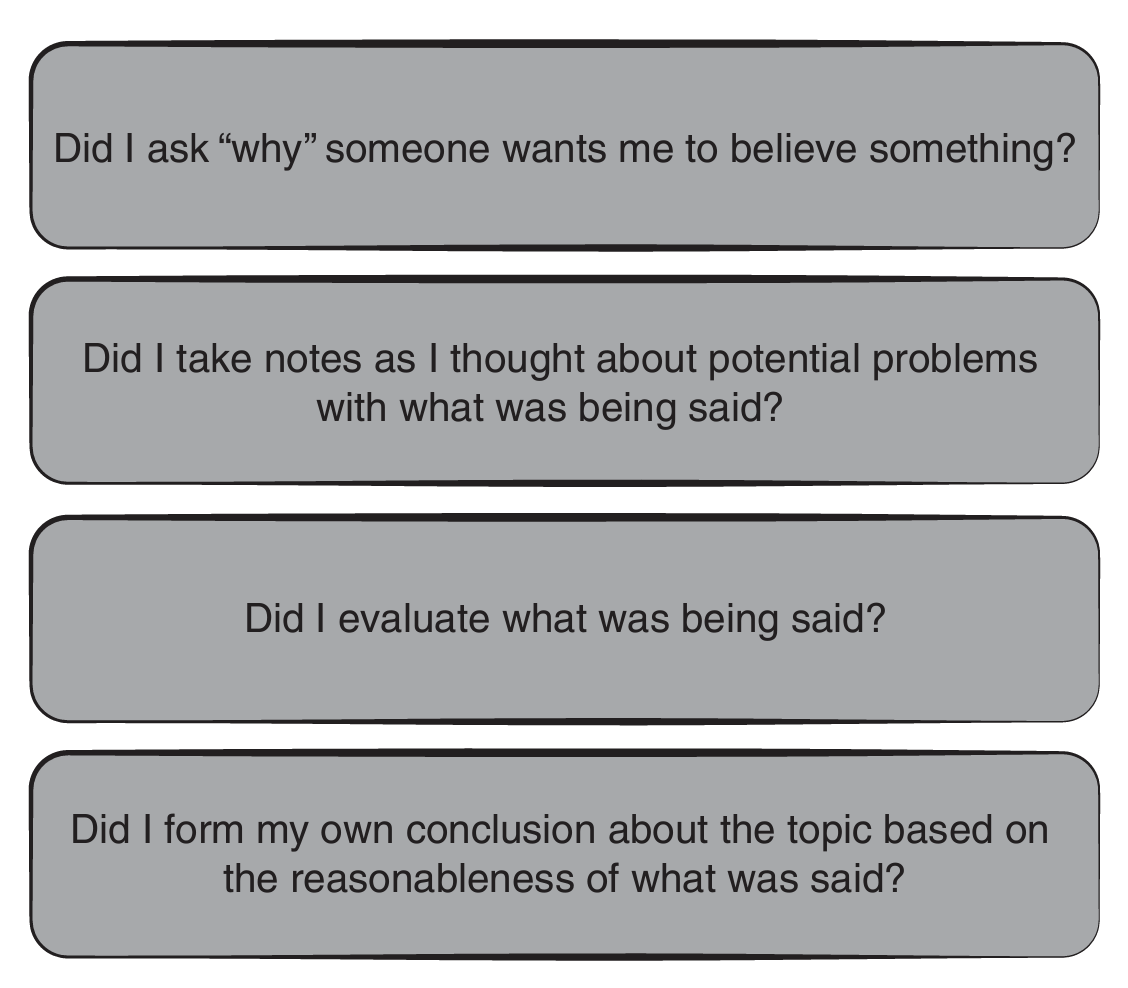

(1) Interpretation, (2) Evaluation, and (3) Metacognition

Interpretation: (goal) How much do you understand about the issue that will be the focus of your thinking

What are the issue and conclusion?

What are the reasons?

What words or phrases are ambiguous?

What are the assumptions?

Evaluation: (goal) How acceptable you believe conclusion is in view of quality of reasons provided to support it.

What are the assumptions?

Fallacies in the reasoning?

How good is the evidence?

Are their rival causes?

Are the stats deceptive?

What significant information is missing?

What are reasonable conclusions are possible?

Metacognition: (goal) monitor and evaluate your thinking during interpretation and evaluation of argument

Monitor your progress

Check your biases and assumptions

use strategic thinking

How can our thinking go wrong?

We prefer “stories” to “statistics”

Story examples:

anecdotes - “in my experience” as told by others

Newspaper/magazine stories

Books - memoirs

Personal websites/YouTube

some podcasts/blogs

testimonials

movies/television - “based on true story”

personal experience - “your own stories”

Examples of statistics (evidence):

Scientific journal articles

Clinical research

Conference presentations

CSD textbooks

some blogs/podcasts

internet presentations of scientific research

Why do we prefer stories to statistics?

stories have attention-grabbing characteristics:

personal - related to someone real

vivid - make a clear impression

emotional - evoke feelings

Stories are easy to relate to personal thus making them seem credible

Stories tap into system 1 thinking because they are easily relatable

We fail to appreciate: stories have potential limitations such as:

SOme details of story emphasized

other details left out or de-emphasized

May contain distortions to:

make the story more entertaining

serve self-interest of the author

seem more credible

Bottom line: stories may seem more credible than they actually are

Wendell Johnson: one of the 1st PhDs in our profession in USA

Widely respected and admired during his time

Published early research describing stuttering

His theory was very influential from 1940s - 1980s, but no longer viewed as credible

Johnson never mentioned Tudor study in his many journal articles chapters and books

The “Monster Study”

Silverman: former student but after Tudor study

First person to describe Tudor’s master’s thesis including selected quotes form her thesis

claimed others associated with Johnson at the time called it the “monster” study

claimed Tudor’s study directly supported Johnson’s theory though Johnson never mentioned or published it

Later after full details of Tudor study published it was clear Silverman left out information contradicting his claim.

Dyer: Riveting two-part story, detailed look at lives of Johnson, Tudor, and the study orphans

Mary Tudor interviewed she believed her study had caused stuttering in orphans

Very emotional story

Received international media attention

The Tudor study became so controversial that the Dyer story prompted researchers to look closely at Tudor’s thesis to see what it actually said.

Ambrose and Yairi (2002) critically reviewed U of Iowa Library copy of Tudor thesis

Described study in detail and they concluded study did not support Johnson’s theory

Addressed ethical issue of orphans as subjects

In 1930’s orphans often subjects in studies

Study never possible today

In sum the “Johnson” story as presented:

Appeared relatable and credible

supported Johnson’s ideas and many believed Tudor’s study cause orphans to stutter

But the story was wrong

Result: Story led many to believe one thing when the reality was something else

Why are we less likely to prefer statistics?

Impersonal - people often reduced to numbers, no “human touch”

Emotionless, abstract, dry, and boring

Intimidating - technical jargon

Transparent - no “surprises”

Statistics depend on system 2 thinking. They require working memory, time, and effort

We fail to appreciate that they are likely more credible

Objective - designed to minimize bias

representative - “lots” of participants

Quantitative - statistical tests

Vetted by experts - peer-reviewed

The bottom line is they are more likely a valid source of information

In sum the genetic story as presented: was intimidating, abstract, and dry, but supported genetic predisposition to stutter and was replicated in other studies

today we believe stuttering has biological foundations

Result: we’ve moved towards biological factors and away from environmental factors as explanations for stuttering and this has meant we are less likely to blame the parents or primary caretakers for its onset

In toto: Natural to believe that “stories” are more credible than “statistics” because stories are easier to relate to and connect with than statistics

But we fail to appreciate stories may be limited and unrepresentative

Whereas statistics may be more credible and complete

therefore, critical thinkers need to be “story skeptics”

In other words, okay to question rather than accept stories at “face calue”

Evidence suggests they are more likely to rely on colleague’s recommendations

Given how powerful “stories” can connect and persuade

Perhaps they can be combined with “statistics”

To influence others in helping relationships

Practice Assignment 1:

Question 1:

Our biases

Question 2:

Specific issue: are college women more attracted to men who may or may not like them, as compared to the ones that like them the most or average

General issue: reciprocal

Question 3:

Conclusion:

Women

B & K Chapter 6:

Deceieves you into thinking reason is valid support for conclusion when it is not\

So easy to use sometimes we do not realize we’re using them

Fallacy: Deception, guile, trickery; a deception; a false statement, a lie

Ad hominem “against the person”: if qualities of person making argument are unacceptable then argument must be unacceptable.

a. Pro hominem “for person”: if the qualities of person making argument are acceptable then argument must be acceptable.

Narrative fallacy: because a story appears to explain the facts, we believe it is accurate when it probably is not. “We prefer stories to statistics”.

Slippery Slope: take this action and it will start inevitable chain reaction that will lead to an unwelcome ending.

Searching for the perfect solution: partial solutions are considered invalid or worthless.

Appeal to popularity: if a lot of people claimed to believe something then must be credible

Appeal to questionable authority: if someone with authority says it, then it must be credible, except in reality, authority expertise is not relevant to claim

Appeal to emotion: if it arouses emotions (sadness, anger, happy, fear, etc.) then it must be credible

Straw man: Misrepresent person’s point of view so that it is easier to knock it down

Either-Or: present only two choices, when there are many.

Explaining by naming: by calling it something it appears to have explained it as well

Planning fallacy: underestimate amount of time to get project completed despite the fact that you should know better by now.

Glittering generality: Positively charged words create halo effect.

Red herring: add information that is sufficiently distracting that one loses track of the original argument.

Begging the question: conclusion is already assumed to be true in the reasons

Post Spring Break

How our thinking can go wrong pt. 2

When asked “Are you good-hearted?”

What comes to mind first? Most of us automatically search our memories for positive or supporting examples and evidence

And when we find it, what do we do? Share, then we Stop!

Whereas, automatic search for negative or contradictory examples and evidence is less likely because it requires more deliberate effort.

Our tendency to search for positive evidence only is known as “confirmation bias” or “myside bias”

Thus, the most fundamental bias that influences all of us, including helping professionals, is confirmation bias, and to make it easier to remember we will from it as follows → (1) we prefer “stories” to “statistics” (2) we seek to confirm not question beliefs.

When we look for evidence to support our beliefs:

Natural for us to look for positive or supporting evidence. first then stop when we find it

But unnatural to look for negative evidence thus we often fail to look for it

Yet we fail to consider: negative evidence provides more complete and balanced picture than positive evidence alone

Negative evidence often informative or provides more balanced view

But there is a dark side to confirmation bias

related to what might happen when we do encounter negative evidence

What might happen if we encounter negative evidence:

Ignore it

Down play it

Distort it in our favor

TED Talk – Kathryn Schulz

The dark side of confirmation bias also reflects a larger concern: We don’t like being wrong.

It doesn’t feel like anything. It feels like being right! It feels like you are on solid ground.

(1) Error blindness: we have no internal cues telling us we are wrong. (2) Cultural message: we are raised to believe “being wrong” means we are lazy, irresponsible dimwits (2a) the only way to succeed is to never make any mistakes. But what if we’re wrong about that! (3)

You are ignorant and thus need to be informed. You are an idiot because even when informed you still don’t get it. Oh you get it but still won’t agree with what I believe therefore you must be evil.

Examples

In sum, Schulz is asking us to appreciate that

Our desire to always be right

combined with our fear of being wrong

meaning we often fail to recognize the value of being wrong

And as a result we might close our minds to other view other possibilities

In toto: we seek to confirm not question our beliefs because natural for us to seek evidence to support our beliefs rather than look for evidence that questions them and when faced with negative evidence we might ignore, downplay, or distort it in our favor failing to consider we might be wrong. Thus missing an opportunity to calibrate our beliefs to the way the world really is than what we wish it would be.

Confirmation bias affects us as clinicians:

Examine evidence fairly and with open mind

claim our personal experience trumps empirical evidence

Nonspeech motor oral exercises:

whistling, blowing, smile-pucker, tongue wagging, cheek puffing

But reviews of evidence raise serious concerns

Theory is unsound

Brain “blowing” doesn’t equal brain “speaking”

Little muscle strength needed for speech

Positive evidence provided by developers only, otherwise evidence is weak non-supportive

Insufficient evidence to support use in clinic

Final thought: How might we counter confirmation bias?

Generate and consider counterarguments:

If you are certain about treatment choice:

Ask: what are the reasons for using it

Then ask: what are the reasons for not using it

Set aside personal beliefs on issue and consider quality of argument:

If you are biased in favor of treatment choice look at it in terms of quality of evidence

Observation is an important skill for audiologists and speech-lang pathologists

Example 1: “The Gorilla Video” suggests that our intuition about our observation skills maybe wrong

If you were told you were to see the gorilla before hand, 90% of students said yes, they believed they would see it.

But in reality about half of us would miss the gorilla in the room

Simon and Chabris (1999) conducted the original Gorilla video study:

Based on 192 participants they found 46% failed to notice gorilla (or woman with umbrella)

Why? Inattentional blindness for unexpected events

We mistakenly believe our brains preserve and include all details from visual scene in front of us, reality: it does not!

Maybe the reason we miss the gorilla because our eyes never see it?

To find out memmert (2006) tracked participants’ eye movements while watching the same Gorilla video

Based on 21 participants he found 60% did not remember the Gorillla and the group wo did not say they saw the Gorilla looked directly at it for a full second, no different than the group who saw it.

Why doesn’t the gorilla enter our conscious awareness?

Example 6: And similar to “The Gorilla Video” when we read material online and “ignore” constant display of ads that appear or scroll right past them

Our attention focused on expected evens: “I expect to see a gorilla” but we failed to notice unexpected events: curtain color change and player leaving but wait could intentional blindness happen to helping professions

Could intentional blindness happen to helping professionals? Yes invisible gorilla strikes again: Inattentional blindness in expert observers

23 radiogists searched for lung nodules in 5 CT scans as their eye movements were tracked

83% missed gorilla, even when eye saw it

Sometimes we even fail to detect changes to people in real world interactions

8/15 (53%) of participants failed to notice change

Some said noticed difference but acted like nothing happened

(67%) failed to notice difference

Even when the two pedestrians had different clothing, height, and voices

In sum our intuition tells us we would notice unexpected visual events

But when our attention is focused we fail to appreciate that we may not consciously be aware of those unexpected events, including helping professionals

we fail to appreciate that our expectations shape our perception

Based on system 1, we expect to see three red hearts because past experience tells us we will. Thus, the black three of hearts goes initially unnoticed but because we were told something is wrong, system 2 eventually sees it

context clues shape our perception

Typical speaking situation: when we speak face-to-face. Visual mouth info complements expected auditory info

What happens if we see a lip position for one sound but we hear another sound, but our brain approximates and mixes the sounds and thinks we hear another sound - McGurk Effect

In sum past experiences and context influence expectations about future perceptions but we fail to appreciate that those expectations sometimes fool us into believing we heard or saw one thing when reality was something different.

Way #3 our thinking goes wrong: we sometimes misperceive the world around us.

It is natural to believe we perceive worlds “as is” because we trust that “seeing is believing”.

And our everyday experience tells us most times it works well

But we fail to appreciate our conscious analysis of an event sometimes misses important unexpected information present in the event.

And our sense can sometimes be deceived

In toto, we sometimes misperceive the world around us because we don’t always see or hear what we think we see or hear. And we’re unaware that our expectations can shape or perceptions

As SLPs or Audiologists: Our assessment and treatment evaluations often rely on what we see and hear

And we have expectations of what we should see and hear

How to counter misperceptions":

Remembering our sense can sometimes be fooled and when the clinical stakes are high

And our attentions is focused on our expectations biased

Then maybe we should pause and ask ourselves: did I miss anything? is it possible I’m wrong?

Practice Assignment 2:

Part 2:

Yes FC presented by Biklen in 1992 appeared to be promising approach especially because it seemed to reveal hidden and untapped potential of individuals with autism

Part 3:

To determine extent to which individual (DM) believed to communicate via facilitator was actually generating his own messages

Results: appeared facilitator was strongly influencing messages of individual

They were selected due to a request from district attorney related to pending litigation

Fronline broadcast provided some clues.

Description of DM appears consistent with populations for which FC is usually recommended.

FC was given an award for her work, and she wan’t new in his life

Worked with DM trusted b DM and trained in FC.

Testing occurred in setting very familiar to Dm and I assume this means DM and facilitator were comfortable

Procedures:

Informal start allowed familiarity with investigators

Picture labeling

Answering questions related to picutes

object naming

description of simple but unique event

All but the last test occurred during shared and unshared condition

Authors scored responses independently. 100% agreement for each response score.

Could have been better if there was blind judges of independent of the authors.

Surveys in helping professions can provide useful information about:

Frequency of use of diagnostic or treatment approaches

attitudes and beliefs about communication disorders, among professionals, the public, and employers, for example

Concerns or issues faced by helping professionals, people with communication disorders or their significant others

In sum surveys in the helping professions can provide useful insights or snapshots in time

if conducted appropriately to minimize bias

Question 4:

1. Scientific method used to minimize wishful thinking by obtaining publicly variable evidence

2. Scientific method based on control

Observation designed to minimize error

Controlled environment to minimize outside influence

Double-blind: facilitator and Dm did not know they were being shown different pictures. Example Shane and Kearns (1994) they used a “double-blind control for possible bias

3. Scientific method based on precise terms

concepts defined to be observable and measurable

Whitchurch et. al. (2011) using measurable items such as self-rating:

Question 5:

1. Evidence can vary in quality

publication in journal does not guarantee high quality

2. Findings do not always agree

However when several independent studies do agree its a good sign

3. Scientific findings do not prove

they support, confirm, or raise questions

Prove: to demonstrate, establish. To establish as true; to make certain; to demonstrate the truth by evidence or argument

4. Personal passion can override scientific passion

even those with best of intentions

5. Findings can be distorted, misrepresented, or oversimplified

especially when presented by others (e.g., mainstream and social media), including other scientists

6. Science is self-critical and self-correcting

usually new findings fine-tune beliefs rather than reject completely

7. highly controlled studies necessary to obtain clear answers

but cost of control may be findings less related to way world really works

8. Scientists’ careers are built on reputation

Related pressures can prompt some scientists to pursue self-interest over scientific interest and public good

Question 6:

Impossible certainty fallacy: assume conclusion should be rejected if it is not absolutely certain

in reality there is always some uncertainty in science

Chapter 9

(1) What is a rival cause?

alternative explanation for outcome may be just as credible as favored explanation

(2) Something that brings about an effect or result, cause → effect, X → Y

(3) Our examples

(4) Our examples: hearing aid → improved speech perception, genetic predisposition → increased likelihood of disorder, and aphasia treatment → increased quality of life

(5) Four questions:

Are there other ways to interpret evidence

What else might have led to difference

Think the opposite, can I see other causal factors

IF this explanation is wrong what else might explain it

(6) causal oversimplification: by claiming a single cause, you “trick” listeners into believing no other causal factors.

Reality: probably several contributing factors

(7) confusion of causation with association: confuse cause with effect

don’t notice connection between two events related to third factor

often referred to as: “correlation does not mean causation”

(8) alternative explanations

did X cause Y

did Y cause X

did Z cause both X & Y

did X & Y influence each other

possible that X & Y are not related at all

Example 1: number of grads increase over time so does pizza consumed

interpretation: as you have more highschool grads the more and more pizza you will have consumed

increased grads → pizza consumption

Z factor: population increased

(9) From study: Higher intelligence results in better critical thinking

Flipped: critical thinking results in higher intelligence

Critical thinking and intelligence influence each other

Some third factor (Z) such as open-mindedness, may result in both higher intelligence and better critical thinking

(10) Our answers

caution: just don’t overapply correlations

correlations can and often do identify a real association

and sometimes the only evidence we have thus, X → Y might be correct causal relationship

Example: smoking → lung cancer

correlational research satisfied many criteria indicating causal connection including:

same association found repeatedly - smokers get cancer much more frequently than non-smokers

association meaningful from biologgical view - smoke irritates and damages lining of lungs

High dose associated with greater effect - heavy smokers more likely to get cancer than light smokers

and lung cancer → smoking is nonsensical

(11) fundamental attribution error:

assign more weight to personal than situational factors when making sense of other’s behavior

whereas, attribute own behavior to situational factors because know own behavior varies across situations

BUT not as aware of same situational variability in others

In sum B & K are asking us to apprevite that:

sometimes alternative explanations may be just as credible as the favored causal explanation

qhen you can try to determine which one cause or combination of causes may be most credible

and correlations are not always causal especially if flipping cause and effect is equally plausible

but be careful not to immediately dismiss all correlations especially when they appear meaningful

Chapter 10

(1) What are statistics

evidence presented as numbers

graphs, tables, and figures are also considered statistics of a descriptive kind

(2) Deceptive statistics

determine how statistics or numbers were obtained

example: descriptive assumptions

how many participants were there? who were they? how did they end up in the study?

what kinds of measures were used to obtain numbers used to calculate statistics?

(3) averages

mode = most frequent number

what happened most often among participants

median = half of sample is above or below this number

what happened to 50% of participants

mean = average occurring number

what is typical number for all participants

range = diff between highest and lowest number

what are extreme numbers among participants

Let’s see how these three “averages” may be useful, not necessarily deceptive

onslow et al. (1994) conducted study to determine if experimental treatment for preschool kids who stutter would reduce their suttering frequency

(4)

act as if you don’t know author’s statistics

what quantitative evidence (or results) would be consistent with conclusion

act as if you don’t know authors conclusion

what conclusion would be consistent with quantitative evidence (or results)

In sum these two B & K strategies are often useful

In sum B & K are asking us to appreciate that

number or statsicitcs don’t always represent what you think they represent although oftentimes they do in scientific research

therefore try to determine how the numbers were obtained

and ask yourself if they still seem meaningful for supporting the reasons and conclusion

Practice Assignment 3

(1) our biases

(2) Issue: will new approach for managing stuttering based on ITE fluency device help author with lifelong severe stuttering problem who is also instructor and researcher in areas related to disorder

(3) conclusion: yes, several months of personal experience, especially while teaching with ITE fluency device appears to hold promise as treatment approach for lifetime

(4) Immediate effect, changing many aspects of stuttering such as:

natural sounding fluent speech with some residual stuttering

no longer feared stuttering

Bypassed neurological source of stuttering

and after 10 months no longer feared stuttering in the classroom

Lifetime of severe stuttering with negative impact on life and work

past treatments failed with qualified exception of DAF (Delayed auditory feedback) device

If his stuttering was mild with minimal impact and almost any treatment he tried worked for him we probably wouldn’t be as impressed by this new device and its effect on him

(6) conducts research and publishes area of stuttering

is a co-inventor of a device in 2001, known as the speecheasy identical to device in this article

but he doesn’t mention his role as a co-inventor when this study was published in 2003

Own shares in company Janus development corporation that markets and sells speecheasy

Is Kalinowski’s judgment of treatment effect unduly influenced by personal/financial investment in device?

Implication: he had nothing to do with device? Minding his own business when unspecified “they” (the inventors?) talk him into trying it?

(7) descriptive assumptions

All reports of device’s benefits were based on personal experience only

no measures provided

no independent observer corroboration

(8) fallacies

narrative fallacy: personal story appears to explain the device’s effectiveness in reducing stuttering

Appeal to emotions: miserable “shuttered” life of living with stuttering filled with false hope but liberated when introduced to the device

Concern: unclear if valid support for device effect given manner of presentation

but stuttering typically does have a negative impact on the person so describing these experiences is not necessarily a fallacy

Straw person (or red herring)

no quantitative measures of stuttering frequency provided

misrepresents concerns about suttering measurement so it appears to be more of a problem than it really is

combined with appeal to popularity

unspecified “many” who agree

(9) types of evidence

case study (or case example) - was most obvious

detailed description of single indivdual’s hands-on experience with a new treatment

used to support conclusion: promising new treatment approach

Personal experience - kalinowski’s life experience with stuttering, treatment, and use of device

concern: selectivity of presentation of info - we do know his standards or making self-judgments of speech improvement

Note: may also be a “testimonial” but given Kalinowski’s experience was presented formally in a journal case study with personal experience as evidence would take precedence over testimonial

Expert/authority - expert in area of stuttering

concern: personal bias, as inventor of device influencing expert opinion

Analogies - combine “difficult to know” subjective experience of stuttering and treatment effect with easier to understand known things

Kalinowski acknowledges “exaggeration” of some analogies

examples: ice skating analogy - uncertainty of stuttering episodes

ebenezer scrooge analogy = freed from stuttering

concern: unclear if these comparisons actually relate to experience of stuttering but still serve useful purpose

(10) is it promising?

(11) How did he sound?

not long after positive media attention like this: over 100 USA SLPs offered device to clients plus SLPs in Canada, South America, Europe, Africa, and Asia

Why? probably because of major media exposure of device’s promise, e.g., “oprah”, “good moring America,” “Monetel Williams,” “people,” and more.

And subseqequent requests from prospective clients and significant others

But not based on clinical study of device because other than kalinowski (2003) no such studies became available until later

(12) what was the report that happened?

it stopped working eventually

(13) What is this type of evidence:

personal experience: his personal contact with the SpeechEasy over time is described in blog

Testimonial: blog was publicly posted and also described in a podcast, so it appears consistent with how we defined testimonial in class

(14) Message of the article

(15) Disclosure Statement

(16) Characteristics of scientific method:

yes this study appears consistent with the three characteristics of the scientific method:

obtained publicly verifiable evidence

Example: study was peer-reviewed and published in AJSLP

Employed controlled observations

Example: included specific speech tasks and self-report measures

Concepts defined and measurable

example: defined how speech behaviors would be counted as stuttered

Wrap-Up:

Evidence from prior studies indicated FAF — a component of the SpeechEasy — is rarely effective during spontaneous speech and if it is the positive effect wears off over time ( e.g., Ingham et al., 1997; Armson and Stuart, 1998).

Why did our professionals embrace the SpeechEasy as a treatment for stuttering based on presentations like media coverage by Good Morning America and Oprah and possibly Kalinowki’s case study

maybe our professionals preferred to view a good “story” with emotionally compelling presentations as sufficient reasons to embrace a treatment before scientific evidence became available

maybe our professionals good intentions to do everything they could to help others clouded their judgment so that they failed to proceed cautiously until more credible evidence was available

What does Babcock’s experience with the SpeechEasy suggest helping professionals should consider before they embrace a treatment that may appear too good to be true?

maybe they should consider that by embracing a treatment prematurely they may have focused only on the positive and failed to consider that if they were wrong there could be potential negative consequences that could be psychologically and financially harmful to those they intended to help

The pros and cons of using the SpeechEasy for people who stutter

objective speech benefits may occur for some but may be short-term or limited to certain situations such as reading aloud

subjective experiences appear to be mixed ranging from reports of increased confidence in speaking to finding the device annoying and unhelpful

SLPs need to recognize that SpeechEasy benefits are variable and unpredictable and not a cure-all

Chapter 12

Question 1: What will your value preferences be as a future helping professional based on what you’ve learned throughout this course?

Question 2: Recognizing alternative conclusions is liberating

Question 3: good thinking