neuroscience; week 5; emotional and relational needs

why does experience matter here?

Need to understand the diversity of experience across individuals

Beware of stereotypes

Need to get away from stigmatising representations, e.g.:

Dangerous”

“Wilful”

“Self-obsessed”

Remember that the prevalence of personality diagnoses is high, so I know I will be talking to some people with such issues today

Diagnosis can be a paradoxical experience in this field

Being diagnosed can feel like you are being written off as:

A problem person

Having no prospect of change

Being diagnosed can be an enormous relief

Recognition that there is a problem

Access to therapy

But the lack of clarity about diagnosis and treatment can be frustrating too

Defining personality

Personality is our tendency towards patterns of behaviour, emotion, cognition, and interaction that show through regardless of the situation we are in

i.e., trait rather than state

For example,

Anxious before an exam – STATE

Anxious all the time – TRAIT

Wanting to do an important job well – STATE

Wanting to do everything perfectly - TRAIT

So, personality can be something that has positive implications if it fits the demands of the world

But it can be a negative influence if it does not fit the world around us or its rules

So when does personality tip over into being a problem?

when it does not fit the context?

when it does not fit any context?

Personality problems in context

consider an aggressive nun or an anxious surgeon

each can be a problem due to the context

Personality disorder: conceptualisations?

Socio-political perspectives

A way of saying ‘that person is weird’

how good are we at agreeing on that?

A way of saying ‘that person is not acceptable’

and we know people disagree on that...

A way of saying ‘that person is not within social bounds’

e.g., detained in Soviet Gulags due to being defined as ‘antisocial’ for having non-fitting views

A way of saying ‘that person is not diagnosable, but is pretty close and probably will have a problem soon, so let’s something about it now’

e.g., early definitions of borderline personality disorders were about being borderline of experiencing psychosis

Medico-legal perspective

socio-political perspectives takes us into the medico-legal perspective:

are we entitled to jail/detain people on the basis of what we believe they might do?

what if we do not and they go on to offend?

levels of caution and politics can still get in the way

Categories vs dimensions

Personality varies along dimensions

so, are personality disorders just extremes on those dimensions?

if so, how to establish a cut-off?

e.g., is the top 0.5% of impulsivity qualitatively different to the top 1.0%?

Big five- openness extraversion (defined in a dimensional way – high or low)

Are personality disorders distinct ‘clumps’ at either extreme

e.g., extreme introversion or extraversion could be seen as a problem

Or a distinct clump at just one end of the dimension?

e.g., we might see extreme neuroticism as a problem, but not extreme stability

Efforts to define personality disorders used to assume that it was simple categories (DSM-IV)

but now are more of a mixture of the two approaches (DSM-5)

Definition of personality disorder under the DSM-IV (1994)

“An enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual's culture”

note that this is a very vague definition

could encompass unusual belief systems (e.g., flat earthers), that might have been quite normal at some points in history

But things got a lot more complex after the DSM-5 taskforce met…

lots of plans for change, based on problems with DSM-IV

but lots of debate

so we still have the same categories – somewhat…

DSM-5 definition of personality disorder (2013)

•“The essential features of a personality disorder are impairments in personality (self and interpersonal) functioning and the presence of pathological personality traits”.

Diagnosis of a personality disorder requires the following criteria:

significant impairments in self (identity or self-direction) and interpersonal (empathy or intimacy) functioning

one or more ”pathological” personality trait domains or trait facets

impairments in personality functioning and the individual’s personality trait expression are relatively stable across time and across situations

diagnosis of a personality disorder requires the following criteria:

impairments in personality functioning and the individual’s personality trait expression are not better understood as normative for the individual’s developmental stage or socio-cultural environment

impairments in personality functioning and the individual’s personality trait expression are not solely due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., severe head trauma)

What are problems with the DSM-5 definition of personality disorder (2013)

define ‘significant’ and ‘normative’

clinicians tend to use diagnosis regardless of substance use, nutrition issues, injury, etc

The other differences in the DSMs

DSM-IV had 10 personality disorders

At the end of a long set of arguments, DSM-5 came out with the same 10 diagnoses

But, DSM-5 included research proposals to allow for future potential change in diagnosis

Level of personality functioning

Personality trait domains and facets

Personality disorder types

Summary of changes to DSM-4/5

DSM-5 maintains diagnostic criteria from DSM-4 and continues to define personality disorders on categorical basis

But it discusses a dimensional approach to the diagnosis of personality disorders and encourages further research on these

Key issues in reaching a diagnosis

Long-term presentations

Independent of biological factors

e.g., drug use; starvation; actual threat

Diagnoses cannot be made at a single clinical meeting

Yet each of these gets ignored by clinicians...so please remember that an element of cynicism is pretty reasonable

And remember that for a lot of people who have complex emotional needs, receiving a diagnosis can be a huge relief, so let’s make it accurate…

usually do not diagnose in childhood and adolescence but…

Tyrer (2022)

Stigma

Personality disorders clusters

Cluster A:

paranoid personality disorder

schizoid personality disorder

schizotypal personality disorder

Cluster B

antisocial personality disorder

histrionic personality

narcissistic personality disorder

borderline personality disorder

Cluster C

avoidant personality disorder

obsessive compulsive disorder

dependent personality disorder

Cluster A: odd/eccentric

Personality disorders (PD) with some schizophrenia-like features

lacking active symptoms, such as hallucinations

Paranoid PD

pattern of distrust and suspiciousness

resistant to challenge by others

Schizoid PD

pattern of separation from social relationships

limited emotional expression and experience

Schizotypal PD

pattern of eccentric ideas, magical thinking

Cluster B: dramatic/ erratic

Personality disorders characterised by impulsive/erratic and/or self-centred behaviours, emotions and thinking

Antisocial PD

–pattern of disregard of other’s rights

–strong links to conduct disorders and criminality

–selfishness and lack of empathy

Borderline PD (Emotionally Unstable PD – ICD)

–pattern of unstable relationships, mood, and behaviour

–efforts to control emotion (e.g., drink; self-harm) and avoid rejection

•Narcissistic PD

–pattern of overestimation of own abilities and accomplishments

–pervasive need for admiration, while not caring about others

–anger when not recognised for their ‘specialness’

–fragility of self-esteem

Histrionic PD

–attention-seeking, need to be the centre of attention

–dramatic behaviour, undue emotional expression

–exaggerated presentation

Cluster C: anxious/ fearful

Personality disorders characterised by anxiety that is lifelong

–not related to any trigger

Avoidant PD

pattern of social avoidance

inadequacy, and sensitivity to others’ views of them

Dependent PD

pattern of dependence on others’ care

submissive, clinging, seek others’ approval/support

Obsessive-compulsive PD

excessive perfectionism (focus on doing the task: forget the goal)

need for order, patterns and control

Summary of diagnostic clusters

three broad clusters with ten diagnoses: odd/ eccentric, dramatic/ erratic and anxious/ fearful

big overlap across clusters and diagnoses

it is rare for a person to only meet one personality disorder criteria

if one meets the criteria for one PD, on average they meet the criteria for 4.5

expected to identify which cluster a diagnosis belongs to but not the criteria for each personality disorder

Epidemiology, comorbidity and course of personality disorders

Prevalence:

No clear onset, so focus on prevalence rather than incidence

The rate found depends on how thorough the assessment is

–many studies use weak measures, and overestimate prevalence hugely

–gender bias in diagnosis? (Women Cluster B & C; Men Cluster A)

The most reliable studies suggest a rate of 10-15% for all personality disorders

–most common: borderline, schizotypal, antisocial, obsessive-compulsive

But the figures really vary hugely

Comorbidity

High rate of co-occurring personality disorders

not so distinct after all?

High rate of comorbidity with:

depression

substance misuse

panic disorder

PTSD

social phobia

eating disorders

neurodiversity

Co-occurance – afraid of abandonment (BPD) – dependent PD

Is a personality disorder for life?

Old viewpoint:

yes, but the symptoms tend to fade after 40 years of age

it is ‘untreatable’

Current View

no, as a large number of cases are not diagnosable a few years later

treatment for some personality disorders is effective in some cases

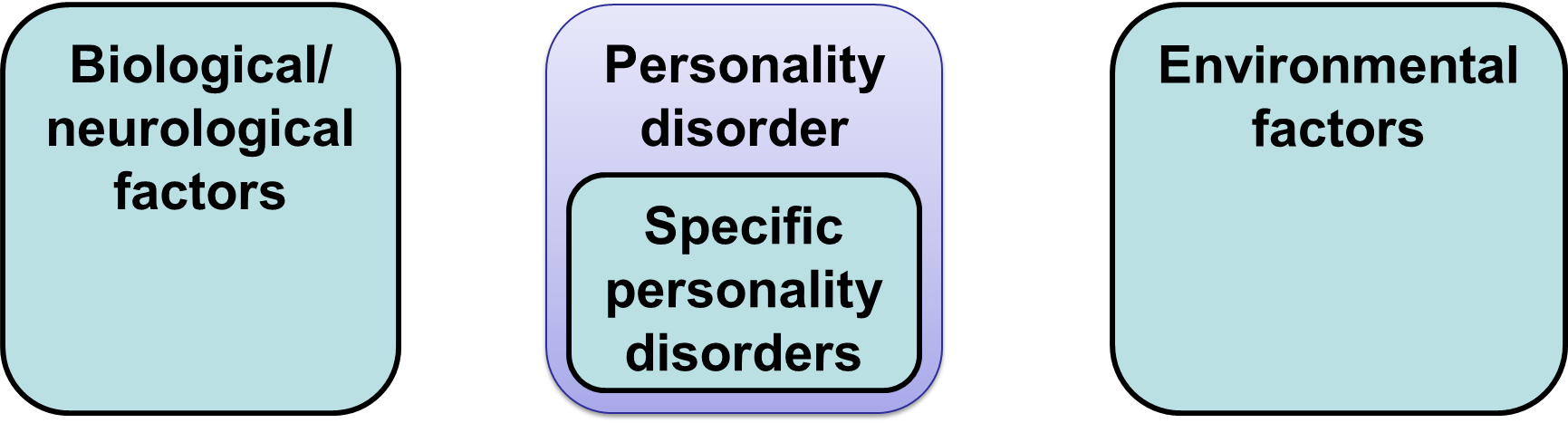

Aetiology of personality disorders

A framework for thinking about aetiology

Factors underpinning Cluster A PDs:

biological/ neurological factors

general

genetics

enlarged ventricles

enhanced startle response

cognitive deficits

lack of link to specific PDs

environmental factors:

general

parental relationships

rejection

abuse

Factors underpinning Cluster B PDs

biological/ neurological factors:

antisocial:

childhood conduct

disorder

genetics

low anxiety

weak fear conditioning

borderline

genetics

limbic system dysfunction

Environmental factors

antisocial

modelling

borderline

trauma/ emotional

invalidation

narcissistic

doting parents?

general

experience driving

schema developing: angry and impulsive child

Factors underpinning Cluster C PDs

biological/ neurological factors

avoidant

genetics

general

? physiological predisposition to anxiety → more fearful anxiety

Environmental factors

avoidant

childhood negative experiences

dependent

fear of rejection

general

experience driving

schema development

Treatment of personality disorders

Limited evidence for most personality disorders

A range of clinical suggestions about such treatment

–all the evidence is for psychological interventions, rather than neurological

Beck et al. (2016) provide a range of clinical guidance based on cognitive-behaviour therapy

Some evidence for other, more integrative therapies

–Cognitive analytic therapy (Ryle)

–Mentalization-based treatment (Bateman)

Psychotherapy for BPD- Cristeau et al. (2017)

meta-anlysis

33 studies

2256 participants

Oud et al (2018)

systematic review and meta-analysis

20 studies

1374 participants

Objective:

Borderline personality disorder affects up to 2% of the population and is associated with poor functioning,

low quality of life and increased mortality. Psychotherapy is the treatment of choice, but it is unclear whether specialized

psychotherapies (dialectical behavior therapy, mentalization-based treatment, transference-focused therapy and

schema therapy) are more effective than non-specialized approaches (e.g. protocolized psychological treatment, general

psychiatric management). The aim is to investigate the effectiveness of these psychotherapies.

Methods: Included randomized controlled trials were assessed on risk of bias and outcomes were meta-analyzed. Confidence in the results was assessed. The review has been reported following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Results: Specialized psychotherapies, when compared to

treatment as usual or community treatment by experts, were associated with a medium effect based on moderate quality

evidence on overall borderline personality disorder severity, and dialectical behavior therapy, when compared to treatment as usual, with a small to medium

effect on self-injury. Other effect estimates

were often inconclusive, mostly due to imprecision.

Conclusion: There is moderate quality evidence that specialized psychotherapies are effective in reducing overall borderline personality disorder severity. However, further research should identify which patient groups profit most of the

specialized therapies.

Best treatment evidence

Schema Therapy (first described by Young et al. 1990; 2003)

Integrative Model – cognitive, behavioural, gestalt, attachment theory,

object relations

Three ways of changing schemas:

Behavioural (Doing)

Feeling (Experiential)

Thinking (Cognitive)

Arntz & van Genderen (2009) manual – first RCT Giesen-Bloo et al. (2006)

Bamelis et al. (2014) ST for Cluster C – American Journal of Psychiatry

Arntz et al. (2022) Group vs Combined Individual & Group. JAMA Psychiatry

Greater focus on:

Therapeutic relationship (rapport)

Using mental imagery techniques

Using Chairwork in therapy

Arntz et al (2022)

largest trial in CERN/PD to date

the combined individual and group schema therapy group had significantly reduced BPDSI (Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index) score compared to the treatment as usual and predominantly group schema therapy groups (which did not significantly differ from one another).

Good treatment evidence

Dialectical behaviour therapy

Behaviourally-based programme

Managing impulsive behaviours and thought processes in BPD

Elements of contingency management, operant conditioning, mindfulness, etc.

Very resource intensive

Designed to manage symptoms effectively, but not to remove the cognitions But main outcome measure is suicidality

personality disorder

Mostnon-psychiatrists are aware of the diagnosis of personality disorder but rarely make it with confidence. In the past, this diagnosis came with a tacit admission that not much can be done, but there is now increasing evidence that treatment can be effective. Epidemiological studies show that 4-12% of the adult population have a formal diagnosis of personality disorder; if milder degrees of personality difficulty are taken into account this is much higher.1 People carry the label of personality disorder with them, and this can influence their care when they come into contact with services, including mental health providers. GPs also carry the clinical responsibility for their patients with personality disorder, and this can be challenging over the long term. This article aims to review the current evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of personality disorder.

What is personality disorder?

The exact definition of personality disorder is open to debate and differs between the two main diagnostic systems used for mental health problems, ICD (International Classification of Diseases) and DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). Temperamental differences between children can be seen from a very young age and probably have a large inherited component. “Personality” refers to the pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviour that makes each of us the individuals that we are. This is flexible and our behaviour differs according to the social situations in which we find ourselves. People with personality disorder seem to have a persistent pervasive abnormality in social relationships and social functioning in general.2 More specifically, there seems to be an enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the outside world and the self that is inflexible, deviates markedly from cultural expectations, and is exhibited in a wide range of social and personal contexts. People with personality disorder have a more limited range of emotions, attitudes, and behaviours with which to cope with the stresses of everyday life. Personality disorder is viewed as different from mental illness because it is more persistent throughout adult life, whereas mental illness results from a morbid process of some kind and has a more recognisable onset and time course.3 A cohort study found good rates of remission in people with borderline personality disorder (78-99% at 16 year follow-up), but remission took longer to occur than in people with other personality disorders and recurrence was more common.4 Evidence from two randomised controlled trials also suggests that most people with this disorder will show persistent impairment of social functioning even after specialist treatment.

Why is personality disorder important?

People with personality disorders experience considerable distress, suffering, and stigma. They can also cause distress to others around them. Epidemiological research has shown that comorbid mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, and substance misuse, are morecommoninpeoplewithpersonalitydisorder,7 are more difficult to treat, and have worse outcomes. One systematic review found that in depression, personality disorder is an important risk factor for chronicity.8 Two recent narrative reviews of the epidemiological literature concluded that personality disorder is also associated with higher use of medical services, suicidal behaviour and completed suicide, and excess medical morbidity and mortality, especially in relation to cardiovascular disease.9 10 One systematic review found an association with violent behaviour.

How is personality disorder diagnosed?

Thetwomajordiagnostic systems in psychiatry have taken very different views on how to revise their classification of personality disorder. There has been growing criticism of a purely categorical approach that requires a decision as to whether a person meets criteria for paranoid, borderline, or antisocial personality disorder. Considerable overlap exists between categories, which do not take into account the wide variation in impairment seen in everyday practice, and reinforce the stigma associated with the diagnosis. There has been debate about whether a dimensional approach using scores for personality traits or applying a simple measure of severity of disorder would be an improvement. Therecently published fifth edition of DSM (DSM-5) has left the previous categorical classification unchanged,12 although an alternative, more complex, classification that was rejected before publication is also included in a later section. The eleventh revision of ICD (ICD-11) is still in preparation,13 but recent publications propose a dimensional approach using five levels of severity. A criticism of this approach has been that the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, which has considerable clinical utility, is lost. The diagnosis is in some sense a misnomer because the primary category to which the condition was thought to be borderline was schizophrenia, and this is no longer the case. However, it is still possible to describe borderline personality disorder using a combination of traits (figure⇓). Controversy remains about diagnosing personality disorder in adolescence, not least because of the current pejorative nature of the diagnosis. Referral to a specialist is recommended for suspected cases.

What do we know about the causes of personality disorder?

Aswithothermentalhealth problems, personality disorders are probably the result of multiple interacting genetic and environmental factors. There is growing evidence for a genetic link, with results from twin studies suggesting heritability of personality traits and personality disorders ranging from 30% to 60%.14 A narrative review of epidemiological studies also suggests that family and early childhood experiences are important, including experiencing abuse (emotional, physical, and sexual), neglect, and bullying

how is personality disorder managed and treated?

Across the range of personality disorders, there is still little evidence for what treatments are helpful. An exception to this is borderline personality disorder, for which there is now a growing evidence base, and (to a lesser extent) antisocial personality disorder. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines have now been producedfor both of these.15 Unusually for people with personality disorder, those with a borderline diagnosis tend to seek treatment, whereas those with antisocial personality disorder and other categories tend to be reluctant to commit to treatment. In view of the prevailing evidence, we will focus this section on the general management and specific treatment of these two categories.

What are the basic principles of managing personality disorders?

Whenworkingwithpeoplewithalltypesofpersonality disorder, it is important to explore treatment options in an atmosphere of hope andoptimism, building a trusting relationship with an open non-judgmental manner. Services should be accessible, consistent, and reliable, bearing in mind that many people will have had previous experiences of trauma and abuse. Consideration should be given to working in partnership, helping people to develop autonomy, andencouraging those in treatment to be actively involved in finding solutions to their problems.

Managing borderline personality disorder

Consider borderline personality disorder in a person presenting to primary care who has repeatedly self harmed and shown persistent risk taking behaviour or marked emotional instability. Primary care doctors should aim to help manage patients’ anxiety by enhancing coping skills and helping patients to focus on the current problems. Techniques for doing this include looking at what has worked in the past, helping patients to identify manageable changes that will enable them to deal with the current problems, and offering follow-up appointments at agreed times. When a patient with borderline personality disorder presents to primary care in crisis, it is important to assess the current level of risk to self and others. People with this disorder require special attention when managing transitions (including changes to and endings of treatment) given the likelihood of intense emotional reactions to any perceived rejection or abandonment. Referral to specialist mental health services can be useful to establish a diagnosis. Also consider referral when a patient with this disorder is in crisis, when levels of distress and risk of self harm or harm to others are increasing.

Specialist treatment

The past 20 years have seen increased emphasis on understanding the underlying problems, symptoms, and states of mind of people with borderline personality disorder and an accompanyingdevelopmentofspecific treatments to target them (box). Dialectical behaviour therapy is a modified version of cognitive behavioural therapy that also uses the concept of “mindfulness” drawnfromBuddhistphilosophy. Several randomised controlled trials focusing mainly on women whorepeatedly self harm have shown reductions in anger, self harm, and attempts at suicide. People with borderline personality disorder are less able than the general population to “mentalise;” that is, to understand their own and other people’s mental states and intentions. Randomised controlled trials of mentalisation based treatment, which focuses on improving mentalising capacity, have shown reduced suicidal behaviour and hospital admissions, as well as an improvement in associated symptoms.6 17 Other therapies, all with trial evidence of effectiveness in reducing borderline symptomsareschemafocusedtherapy,1819 transference focused therapy,20 and cognitive analytic therapy.21 In addition to improving core symptoms, schema focused therapy improved psychological functioning and quality of life; transference focused therapy improved psychosocial functioning and reduced inpatient admissions; and cognitive analytic therapy improved interpersonal functioning and overall wellbeing and led to a reduction in dissociation (splitting of the personality). Asystematic review of randomised trials identified two other treatments with evidence of effectiveness in this group of patients. The first, problem solving for borderline personality disorder, is an integrated treatment that combines cognitive behavioural elements, skills training, and intervention with family members. It can reduce borderline symptoms and improve impulsivity—the tendency to experience negative emotionsandglobalfunctioning.22 The second, manualassisted cognitive treatment, aimed at reducing deliberate self harm, was successful in a study of patients with borderline personality disorder who self harm.23

Psychological treatments with the current best evidence for borderline personality disorder

Dialectical behaviour therapy

Developed as a modified version of cognitive behavioural therapy, it also incorporates the concept of “mindfulness” drawn from Buddhist philosophy. The treatment focuses on emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness through individual therapy, group skills training, and telephone coaching.

Mentalisation based treatment

Anadaption of psychodynamic psychotherapy grounded in attachment theory, which emphasises improving patients’ ability to “mentalise”—that is, to understand their own and other people’s mental states and intentions. The treatment is delivered in a twice weekly individual and group therapy format or as part of daily attendance at a treatment centre.

Transference focused therapy

A form of psychodynamic psychotherapy derived from Otto Kernberg’s theory of object relations, which describes contradictory internalised representations of self and others. It focuses intensely on the therapy relationship and is delivered as twice weekly individual sessions aimed at the integration of split off aspects of the personality.

Cognitive analytic therapy

Brief focused therapy that integrates ideas from psychoanalytic object relations theory and cognitive behavioural therapy. A collaborative therapy that uses diagrams and letters to help people to recognise and revise confusing patterns and mental states, it is delivered individually over 24 weeks with follow-ups.

Schema focused therapy

A development of cognitive behaviour therapy founded by Jeffrey Young, which blends elements of Gestalt therapy, object relations, and constructivist therapies. It identifies and modifies dysfunctional patterns (schemata) made up of patients’ memories, feelings, and thoughts about themselves and others. It is usually delivered as once or twice weekly individual therapy.

Effective management and care coordination

Specialist treatments are not generally available in the community, andit maybedifficult to motivate people struggling with chaotic lifestyles and unstable support systems to engage with them. Evidence is emerging that well structured general psychiatric management can be as effective as branded specialised treatments when delivered under research conditions.5 In this randomised trial, general psychiatric managementinvolvedcasemanagementandweeklyindividual sessions using a psychodynamic approach that focused on relationships and management of symptom targeted drugs. Good care coordination within a community mental health setting is key to stabilising patients, some of whom may later receive more specialist interventions. Indeed, the type of therapy maynotbeimportant,butrather that managementis consistent, reliable, encourages autonomy, and is sensitive to change. Management should be systematic and preferably manualised (guided by a “manual” for the therapist with a series of prescribed goals and techniques to be used during each session or phase of treatment) to provide a clear model for patient and therapist to work with. This helps the mental health professional to deal with common clinical problems, such as self harm and risk of suicide, by talking with the patient about any precipitants to unmanageable feelings, giving basic psychoeducation about managing mood states, and encouraging problem solving and the sharing of risk and responsibility. In addition, close attention should be paid to any emerging problems in the therapeutic alliance.

Are there any drug treatments available for borderline personality disorder?

There is no clear evidence for the efficacy of drugs for the core borderline symptoms of chronic feelings of emptiness, identity disturbance, and abandonment. Some randomised trials have shown benefits with second generation antipsychotics, mood stabilisers, and dietary supplements of omega-3 fatty acids,25 but these are mostly based on single studies with small sample sizes and are not recommendedbyNICE.15Antidepressants may be helpful only in the presence of coexisting depression or anxiety.

Managing antisocial personality disorder

The treatment of people with antisocial personality disorder will be facilitated by working within a clearly described care pathway because a diverse range of services are often be involved. The pathways should specify likely helpful interventions at each point and should enable effective communication between clinicians and organisations. Locally agreed criteria should be established to facilitate transfer between services with shared objectives and a comprehensive assessment of risk. Services should consider establishing multiagency antisocial personality disorder networks that actively involve service users. Once established, they can play a central role in training, the provision of support and supervision to staff, and the development and maintenance of standards. Although it may not be appropriate or possible to provide specific therapeutic interventions for antisocial personality disorder in primary care, GPs still need to offer treatment for patients with comorbid disorders in line with standard care. In doing so, GPs should be aware that the risk of poor adherence, misuse of drugs, and drug interactions with alcohol and illicit drugs is increased in this group. It may be helpful to liaise closely with other agencies involved in the care of these patients, including the criminal justice system and drug support workers. Local schemes are available in primary care in the UK for the management of patients who have been violent or threatening towards their GPs or other primary care staff. Assessment of risk in primary care should include history of violence, its severity, and precipitants; the presence of comorbid mental disorders; use of alcohol and illicit drugs and the potential for drug interactions; misuse of prescribed drugs; current life stressors; and accounts from families or carers if available.

Specialist treatments

Robust evidence for the effectiveness of specific psychological interventions in antisocial personality disorder is currently lacking.26 However, NICE guidelines suggest the use of group based cognitive and behavioural interventions that focus on the reduction of offending and other antisocial behaviour.15 Particular care is needed in assessing the level of risk and adjusting the duration of programmes accordingly. Participants will need to be supported and encouraged to attend and complete programmes. People with dangerous and severe personality disorder will often come through the criminal justice system and will require forensic psychiatry services. Treatments (including anger management and violence reduction programmes) will essentially be the same as above but will last longer. Staff involved in such programmes will require close support and supervision.

Are there any drug treatments available for antisocial personality disorder?

Nospecific drugs are recommended for the core symptoms and behaviours of antisocial personality disorder (including aggression, anger, and impulsivity).27 Drugs may be considered for the treatment of comorbid disorders.

Other treatments

Therapeutic communities, which provide a longer term, group based, and often residential approach to therapy, have a long history in the treatment of personality disorder, but there is no evidence for their effectiveness. In the UK, the Department of Health set up pilot projects for management of personality disorder in 2004-05. One of these, the Service User Network model, offers community based open access support groups for people with personality disorder, with service users engaged in the design and delivery of the service.28 Analysis of routine data, together with a cross sectional survey, showed that the service attracted a large number of people with serious health and social problems and that use of the service was associated with improved social functioning and reduced use of other services. Nidotherapy (nest therapy) is a new treatment approach for people with mental illness and personality disorder, which involves manipulation of the environment to create a better fit between the person and his or her surroundings, rather than trying to change a person’s symptoms or behaviour. Evidence fromasystematicreviewinwhichonlyonestudymetinclusion criteria showed an improvement in social functioning and engagement with non-inpatient services.

What are the problems in everyday practice?

Personality disorder affects the doctor-patient relationship. Misunderstandings and even angry reactions are not uncommon and consistency, clarity, and forward planning are all important in managing the relationship. The diagnosis of personality disorder should never be given to a patient whom the doctor simply finds “difficult.” There is evidence of a disparity between a formal diagnosis of personality disorder achieved using a research interview and the diagnoses made by GPs.30 However, it is important to be aware that a diagnosis of comorbid personality disorder is a possibility in patients who do not respond to treatment or seem particularly difficult to manage. Asimple eight item screening interview (standardised assessment of personality: abbreviated scale) is useful in this respect.31 It is useful to have clear management plans in place to deal with recurring patterns of crisis, with agreement between GP, specialist mental healthcare, and the service user about potential options for managing likely problems, possible sources of support and advice, and when to urgently refer to specialist care. Efforts need to be made to challenge stigma and unhelpful attitudes of healthcare professionals,32 develop professional skills in understanding and managing difficult encounters with challenging patients,33 34 and promote engagement in psychological therapy if it is likely to be helpful. However, people with comorbid substance misuse may face problems in accessing psychological therapies (some services do not offer them to these people), specialist therapies may not be locally available, and barriers persist in accessing mental healthcare for people with personality disorder in the UK despite policy guidance to the contrary.35 No patient should be excluded from mental health services because he or she has a personality disorder, nor should the incorrect notion that personality disorder is all pervasive and immutable be used to deny people access to valuable therapeutic interventions.

Tips for non-specialists

Consider personality disorder in people who are difficult to engage and do not respond to treatment—for example, those who do not respond to treatment for depression. Try to maintain a consistent and non-judgmental approach even when “underfire” from a person who is emotionally aroused or wound up It is more important to recognise the general problem of an enduring pattern of difficulty in a wide variety of social contexts, and a limited repertoire of coping skills, than to diagnose a particular subtype of personality disorder. Make plans for crisis management, especially recurrent crises, such as repeated self harm or threats of self harm. Explore possible therapeutic avenues with specialist care; don’t let the label be a reason for not referring.