L11 : The microstructure of Steel

Learning Objectives:

Be able to differentiate steels vs. cast irons based on carbon content or microstructure

Typically 2.5-4wt. %C. Fast cooling forms large fraction of Fe3C phases (brittle). For structural applications must be heat treated to decompose Fe3C into Fe+C (grey iron).

Be able to recognise differences in microstructure between ferritic and austenitic steels and how you could promote them.

Austenitic - large C solubility, easy deformation and twinning (good formability). Generally promoted with Ni

Ferritic - low solubility leads to Fe3C precipitation, increases strength. Generally promoted with Cr

Understand equilibrium cooling of ferrite from austenite

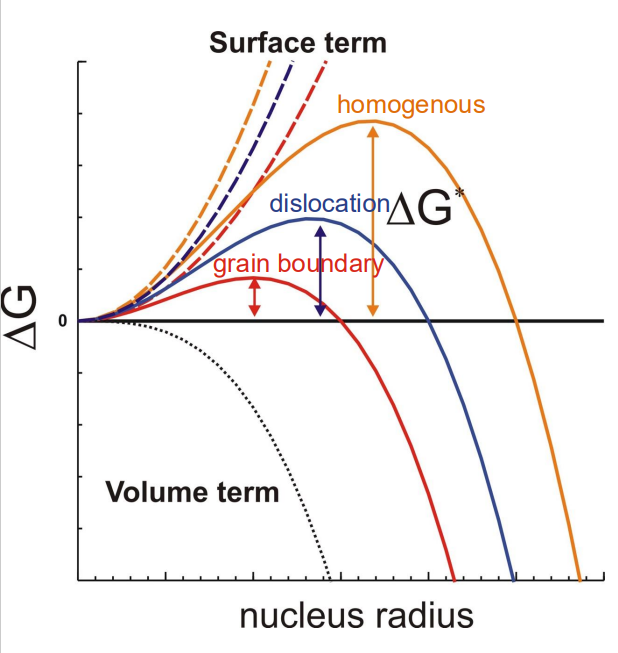

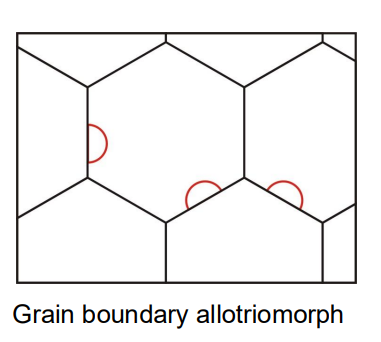

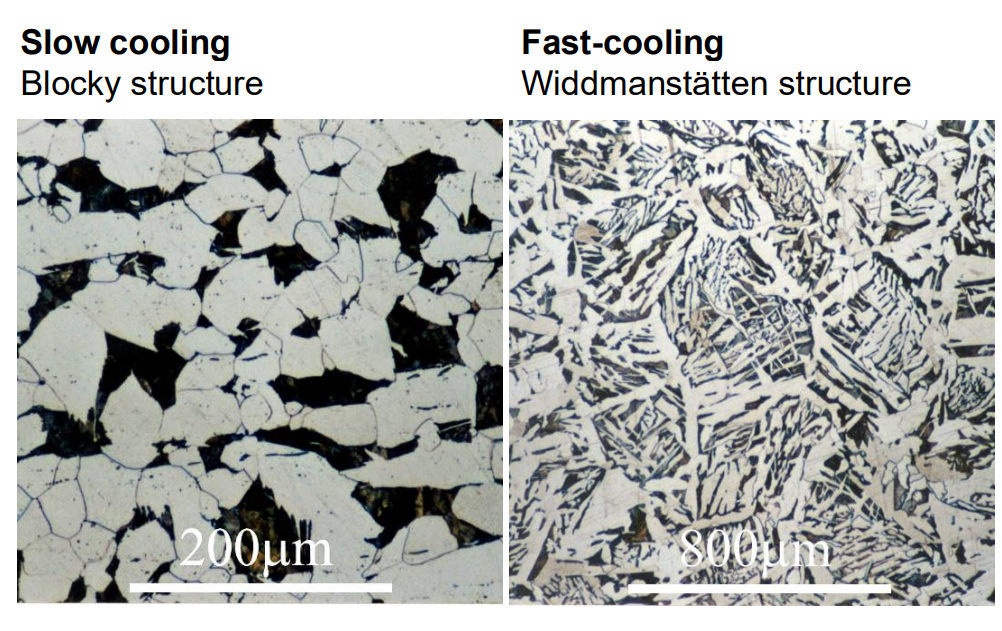

Low undercooling leads means nucleation occurs on GBs and forms a blocky (equiaxed) structure to minimise surface energy

Understand how situation changes under faster cooling

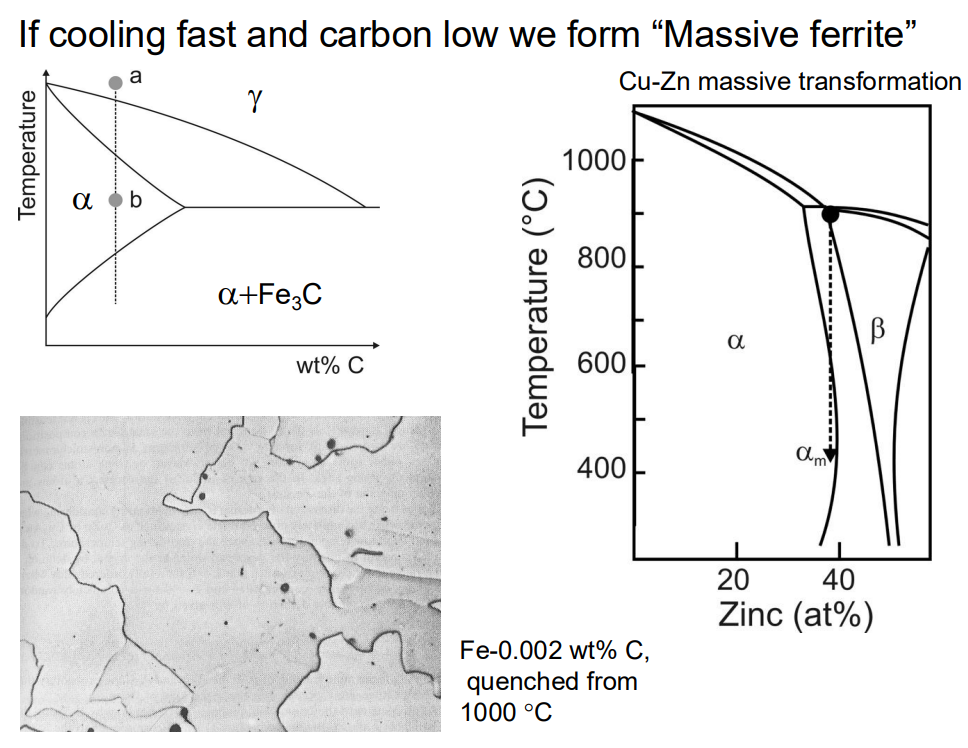

Widdmanstättan (High undercoolings) – interface velocity controlled, α grows in laths. – Slow, coherent interfaces with a (111)γ :(110)α orientation relation – large grain size → Widmanstätten structure, lack of nucleation sites. Massive ferrite (very high undercoolings) – no carbon diffusion required, massive γ→α transformation

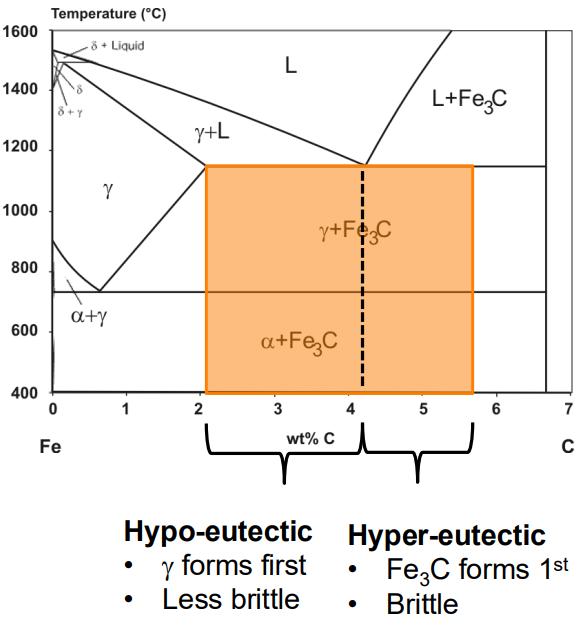

Differentiating Steels vs. Cast Irons:

Carbon Content:

Steels typically contain less than 2 wt% carbon.

Cast irons have more than 2 wt% carbon.

Microstructure:

Steels with low carbon content (e.g., 0.1 wt% C) have a microstructure dominated by ferrite with some pearlite (a mixture of ferrite and cementite). At 0.8 wt% C, the microstructure is entirely pearlite. Above 0.8 wt% C, cementite forms first on grain boundaries, with pearlite forming in the remaining grains.

Cast irons can be classified as white cast iron (no graphite, cementite forms)

or grey cast iron (graphite forms).

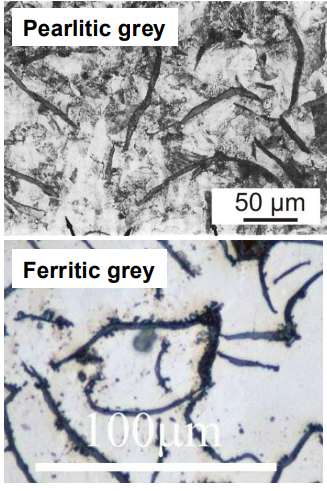

Grey cast irons are further divided into ferritic grey cast iron (graphite forms at lower temperatures) and pearlitic grey cast iron (cementite forms at lower temperatures).

Spheroidised cast iron has spheroidal graphite nodules, making it less brittle.

2. Differences in Microstructure Between Ferritic and Austenitic Steels:

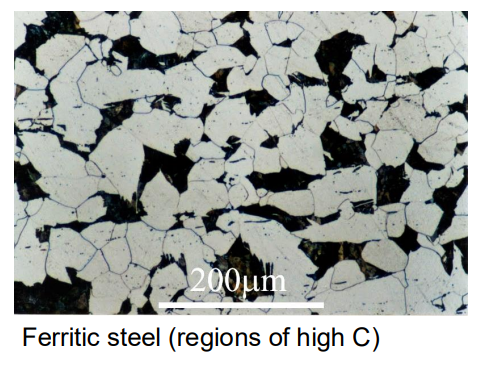

Ferritic Steels:

These steels have a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure and are primarily composed of ferrite. They are magnetic and have lower strength but good ductility.

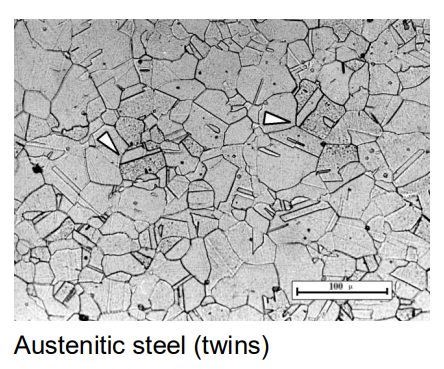

Austenitic Steels:

These steels have a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure and are primarily composed of austenite. They are non-magnetic and have higher strength and corrosion resistance. Austenitic steels are stabilized by adding elements like nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr), which keep the austenite structure stable down to room temperature.

Promoting Ferritic or Austenitic Microstructures:

To promote ferritic microstructure, you can use low carbon content and avoid adding austenite-stabilizing elements like Ni.

To promote austenitic microstructure, you can add austenite-stabilizing elements like Ni and Cr, which prevent the transformation to ferrite.

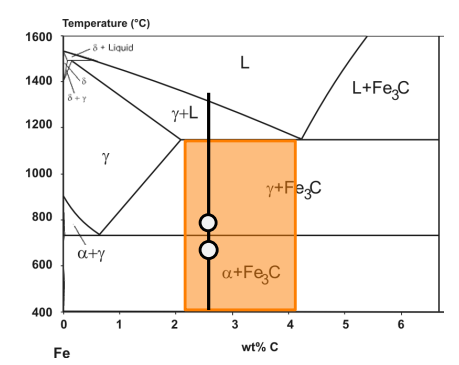

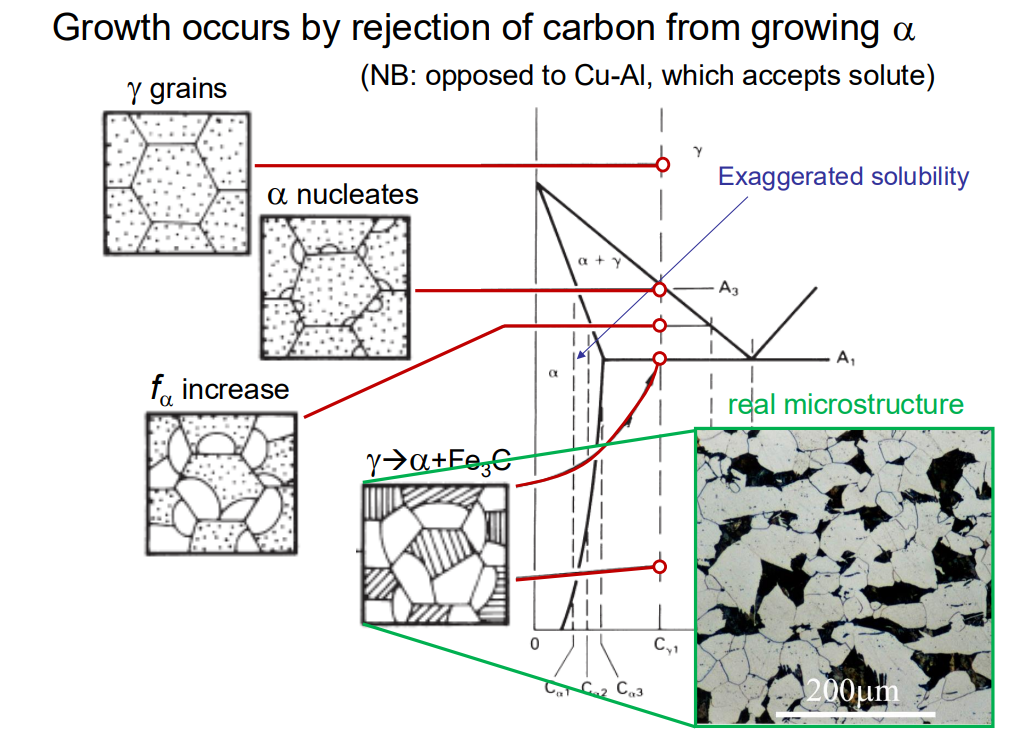

3. Equilibrium Cooling of Ferrite from Austenite:

During equilibrium cooling, ferrite forms from austenite as the temperature drops below the A3 line on the Fe-C phase diagram. Ferrite nucleates on the grain boundaries of austenite grains because grain boundaries are sites of easier nucleation. As cooling continues, ferrite grows into equiaxed grains, and the remaining austenite transforms into pearlite (a mixture of ferrite and cementite) at the eutectoid temperature (727°C).

The type of ferrite that forms depends on the cooling rate and austenite grain size. At low cooling rates, ferrite tends to form as equiaxed grains (grain boundary allotriomorphs)

At higher cooling rates, Widmanstätten ferrite (needle-like structure) may form.

4. Changes Under Faster Cooling:

Under faster cooling, the formation of ferrite changes significantly:

Widmanstätten ferrite forms when the cooling rate is higher, leading to elongated, needle-like ferrite grains. This occurs because incoherent interfaces grow more rapidly at higher undercooling.

Massive ferrite can form if the cooling rate is rapid enough to prevent long-range diffusion of carbon. In this case, ferrite forms with the same carbon content as the austenite, and the transformation occurs without a compositional change. This results in irregular grain boundaries and high growth rates.

At very high cooling rates, pearlite formation is suppressed, and other non-equilibrium phases like bainite or martensite may form.

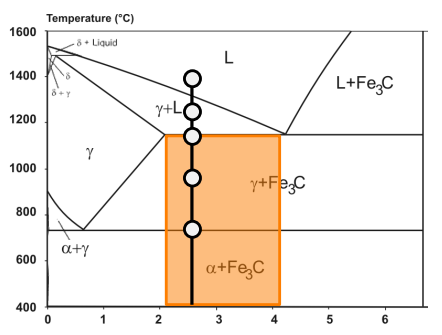

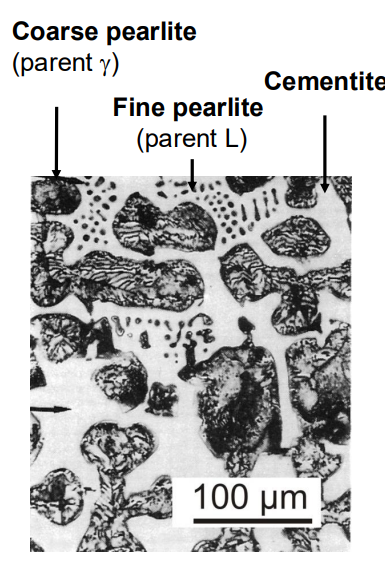

5. Pearlite Formation:

Pearlite forms via the eutectoid reaction when austenite with 0.8 wt% C is cooled through 727°C. The reaction is:

γ→α+Fe3C

Pearlite consists of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite. The interlamellar spacing (distance between ferrite and cementite layers) depends on the cooling rate:

At higher temperatures (slower cooling), pearlite is coarser (larger spacing).

At lower temperatures (faster cooling), pearlite is finer (smaller spacing).

Knowt

Knowt