BIOC331 In Class

1/23 - Quantum Mechanics Introduction

QM can be defined as a consequence of the duality of light & matter

Light can behave like a wave and a particle

Matter is both a particle and a wave

Waves

Oscillates in space and time

Properties:

peak-to-peak distance AKA wavelength (λ)(meters)

may travel at a specific speed (m/s)

all light waves travel at the speed of light in a vacuum (C = 2.998×10^8 m/s)

frequency (ν)(cycles/s, s^-1, Hz)

how many peaks pass by a point per second

λν = C

λ and v are inversely related

Wave number (𝜈̃)

v/C

Red light has a wavelength of about 650nm. What is the frequency of red light?

λν = C → ν =C/λ

ν = 2.998×10^8 m/s / 6.5×10^-7 m = 4.6×10^14 s^-1

Light as a particle

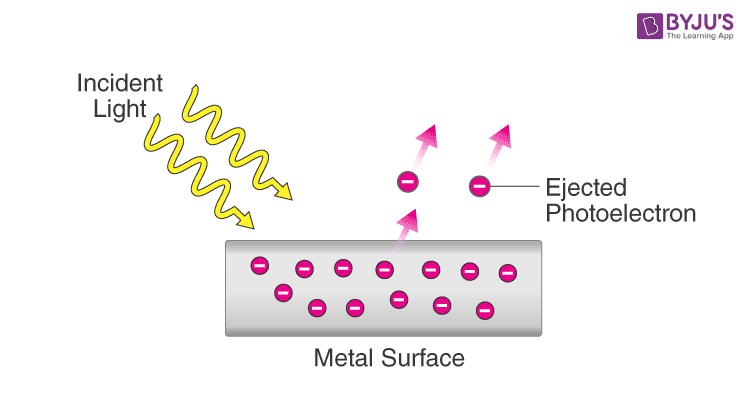

Photoelectric effect

Ejects e- off metal surface using energy from light

Observed:

When light below a certain threshold frequency was shone on the metal, no electrons were ejected, no matter the intensity/brightness of the light (Brighter light = higher amplitude)

Once light has a frequency above the threshold, e- are ejected

Increasing the frequency further will eject e- with higher kinetic energy → move faster

Increasing the amplitude/brightness/intensity, more e- are ejected but with the same kinetic energy as before

Waves → if amplitude increases, energy must increase

Particles → if frequency increases, energy increases per particle

If brightness increases, number of particles increases

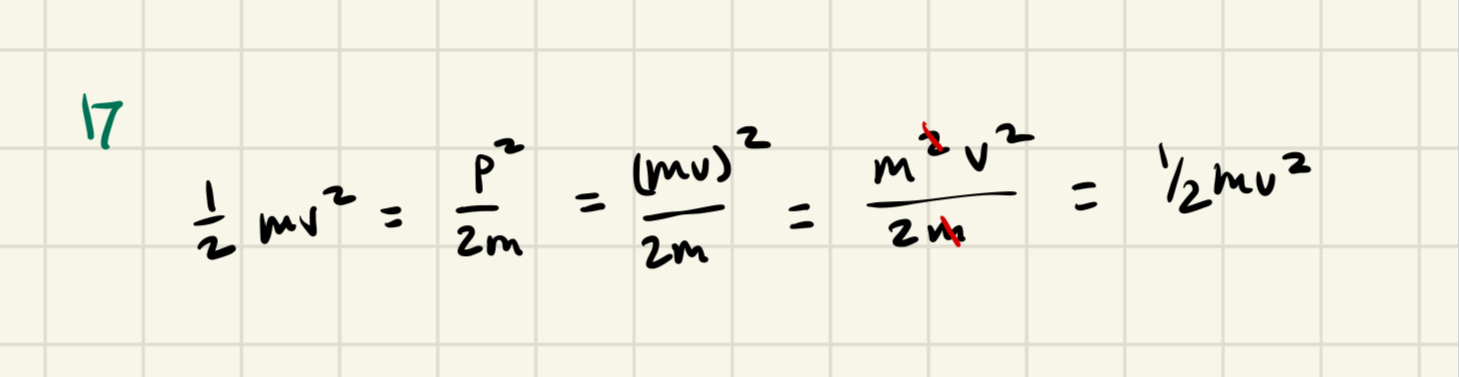

KE= 1/2mv²

y=mv+b

Slope of the line is a constant, h / Planck’s constant = 6.626×10^-34 J*s

1/2mv²=hv → energy per photon depends on the frequency, leftover energy goes into increasing the KE of the e-

λν = C

Ephoton= hv

Ephoton = hC/λ

A photon produced by an X-ray machine has an energy of 4.70×10^-16J. What is the frequency of the photon?

Ephoton= hv

4.70×10^-16 J= hv

v = 7.09×10^17 s-1

Would the frequency of violet light be higher or lower than the previous frequency?

Lower

Would the wavelength of a radiowave be longer or shorter than the previous wavelength?

Longer

Light as a particle and a wave

KE=1/2mv²

λdB = h/m*v= h/P, where P = momentum

Estimate the de Broglie wavelength of a baseball thrown by an average Red Sox pitcher.

λdB = h/m*v

λdB = 6.626×10^-34 J*s/(0.1kg)(10m/s) = 6.626×10^-34 m

Where the baseball is 0.1kg and travels at 10m/s

Can be ignored, because the value is so much smaller than any length scale of matter that is relevant

Estimate the de Broglie wavelength of an electron traveling at 0.1% the speed of light.

λdB = h/m*v

λdB = 6.626×10^-34 J*s/(9.11×10^-31 kg)(2.998×10^5m/s) = 2.44×10^-9 m / 24Å

Cannot be ignored, because it is spread out over molecular length scales

1/27 - Quantum Mechanics p2

The minimum frequency of light that can cause the photoelectric effect in cesium is 4.60×10^14 Hz. If light with a wavelength of 4.40×10^-7 strikes a cesium surface, calculate the dB wavelength of the emitted photoelectrons.

KE=Ephoton-minimum frequency

1/2mv²=h(C)/λ - hv0

1/2(9.11×10^-3kg)v² = (6.626×10^-34 Js)(2.998×10^8 m/s)/4.40×10^-7) - (6.626×10^-34Js)(4.60×10^14)

v=567,000 m/s

λdB= h/mv

λdB= (6.626×10^-34 Js)/(9.11×10-31)(567,000 m/s)

λdB= 1.28nm or 1.28×10^-9 m

Quantum Mechanics

λdB for an e- was big enough to be significant over molecular length scales → cannot be ignored like it can for larger length scales

e- and other small mass must be treated as waves

Quantum mechanics is a branch of physics that focuses on accounting for the wave-like nature of matter

Quantized → can only exist in discrete quantities, cannot take on all values, stairs/ladder

Continuous → can exist in any quantity, can take on any value, ramp/elevator

Why does treating matter like a wave lead to quantized states?

Waves, when constrained, can only take on certain discrete states

Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

A quantum-mechanical object does not simultaneously have a well-defined position (as it does when acting like a particle) and a well-defined momentum (as it does when acting like a wave)

σx σp ≥ h/4π

σx = uncertainty in position

σp = uncertainty in momentum

Schrodinger Equation

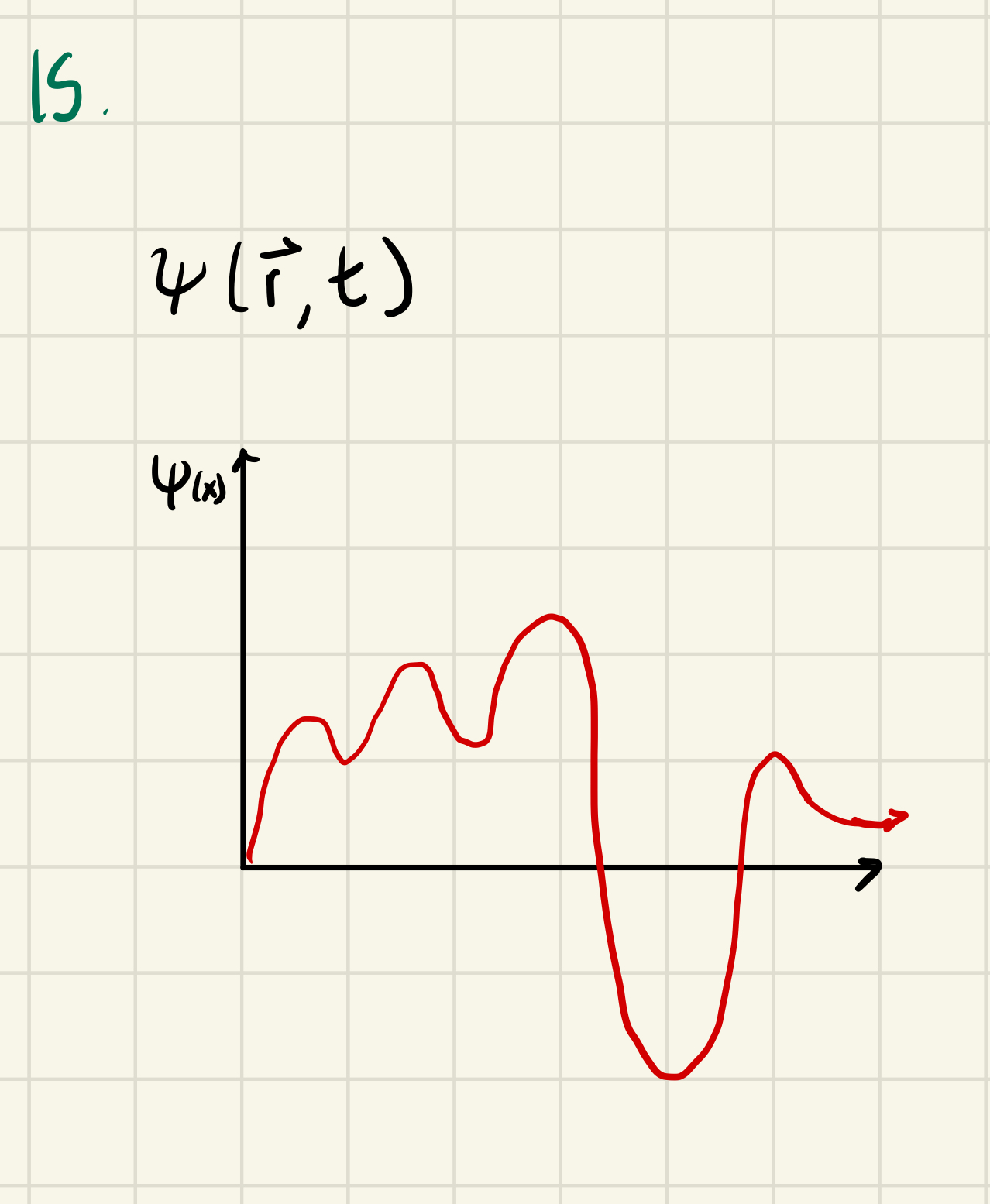

A QM object is described by a wave, represented by a function called a wave function

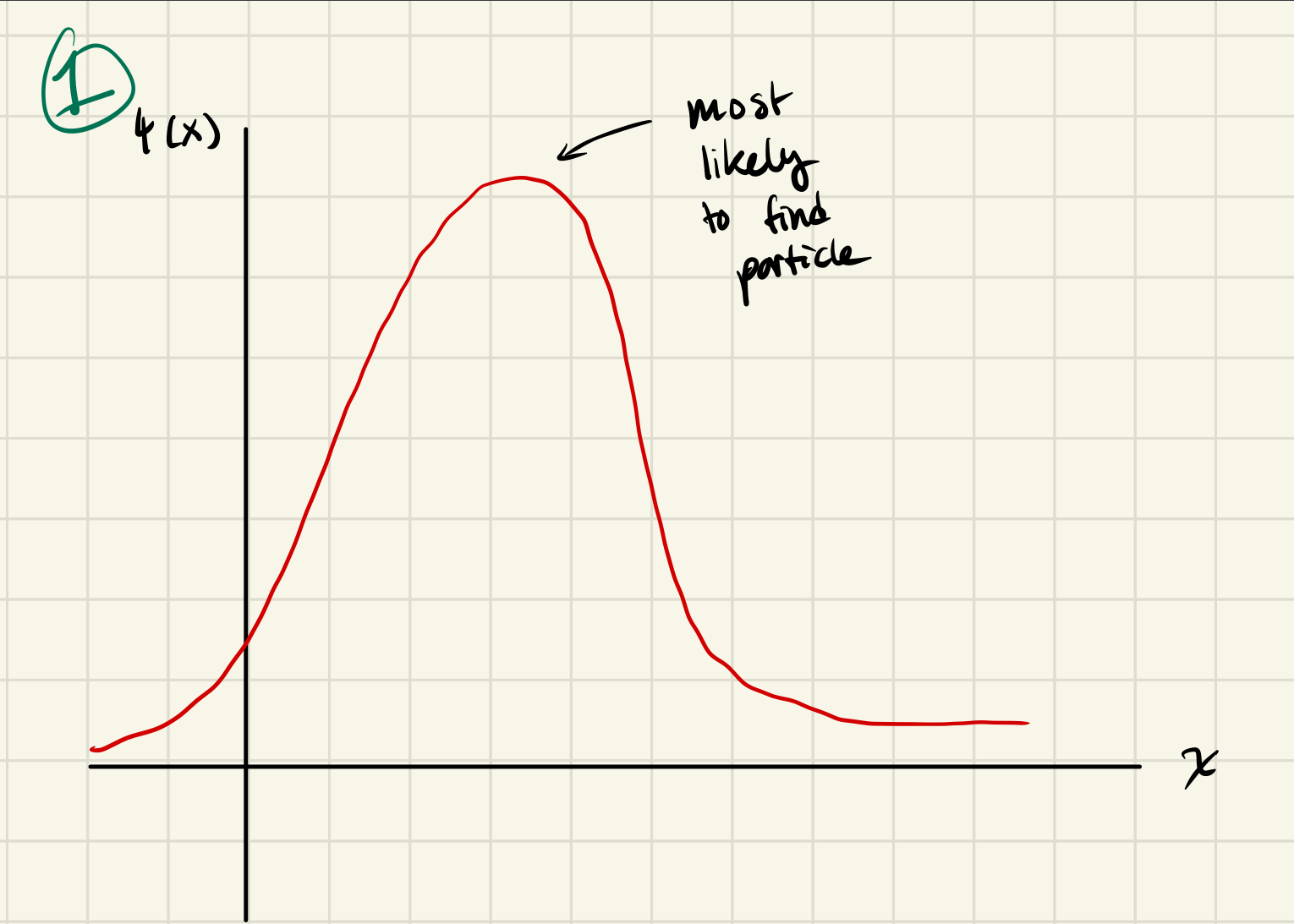

ψ aka “psi” gives you the amplitude of an object as a function of space

|ψ|² gives you the probability that, if you were to measure the particle’s location, you would find it at a given location

How do we get ψ for a particular object?

Solve Schrodinger Equation

→ for a one dimension, time-independent Schrodinger Equation:

-ℏ²/2m d²/dx² ψ(x) + V(x)ψ(x) = Eψ(x)

ℏ = h/2π

m = mass of object

d²/dx² = second derivative

ψ(x) = wave function

V(x) = potential energy of the system: mathematically describes the constraints and environment of the object

high V(x) value = unstable, unhappy

low V(x) value = stable, happy

E = energy

When we start to solve, we only know m and V(x)

plug those in to start

Goal: solve for ψ(x) and associated Es (energies)

2 unknowns, one equation → differential equation, infinite # of discrete solutions

Shorthand notation for Schrödinger

Ĥ ψ(x) = E ψ(x)

Ĥ aka “Hamiltonian Operator” = -ℏ²/2m d²/dx² + V(x)

Operator is a set of symbols that acts on what comes afterwards (only to the right)

Ex: Â = d/dx

f(x) = 5x

What is Âf(x)?

= d/dx(5x) = 5

Ex: Â = d²/dx²

f(x) = e^5x

What is Âf(x)?

= d²/dx²(e^5x) = 25e^5x

Ex: Â = d/dx+5x

f(x) = 2x²

What is Âf(x)?

= d/dx+5x(2x²) = 5x(2x²) = 4x + 10x³

Goal: Find ψ(x) such that when operated on by Ĥ, we get back ψ*E

Ĥ ψ(x) = E ψ(x)

ψ(x) = eigenfunctions

E = eigenvalue

Ĥ = operator

d/dx(e^3x) = 3(e^3x) → 3 is eigenvalue and (e^3x) is eigenfunction

1/29 Schrodinger Equation + PIB

Eigenfunctions of d/dx

d/dx (e^3x) = 3(e^3x)

3 = eigenvalue

e^3x = eigenfunction

d/dx = operator

Generic equation: d/dx e^kx = k(e^kx)

Schrödinger equation

You can only solve Schrödinger exactly for a handful of V(x) values → only so many environments

Can:

Solve an “exact” model exactly (with exact math) ← hard

Solve an approximate model exactly

Solve an “exact” model approximately

Solve an approximate model approximately

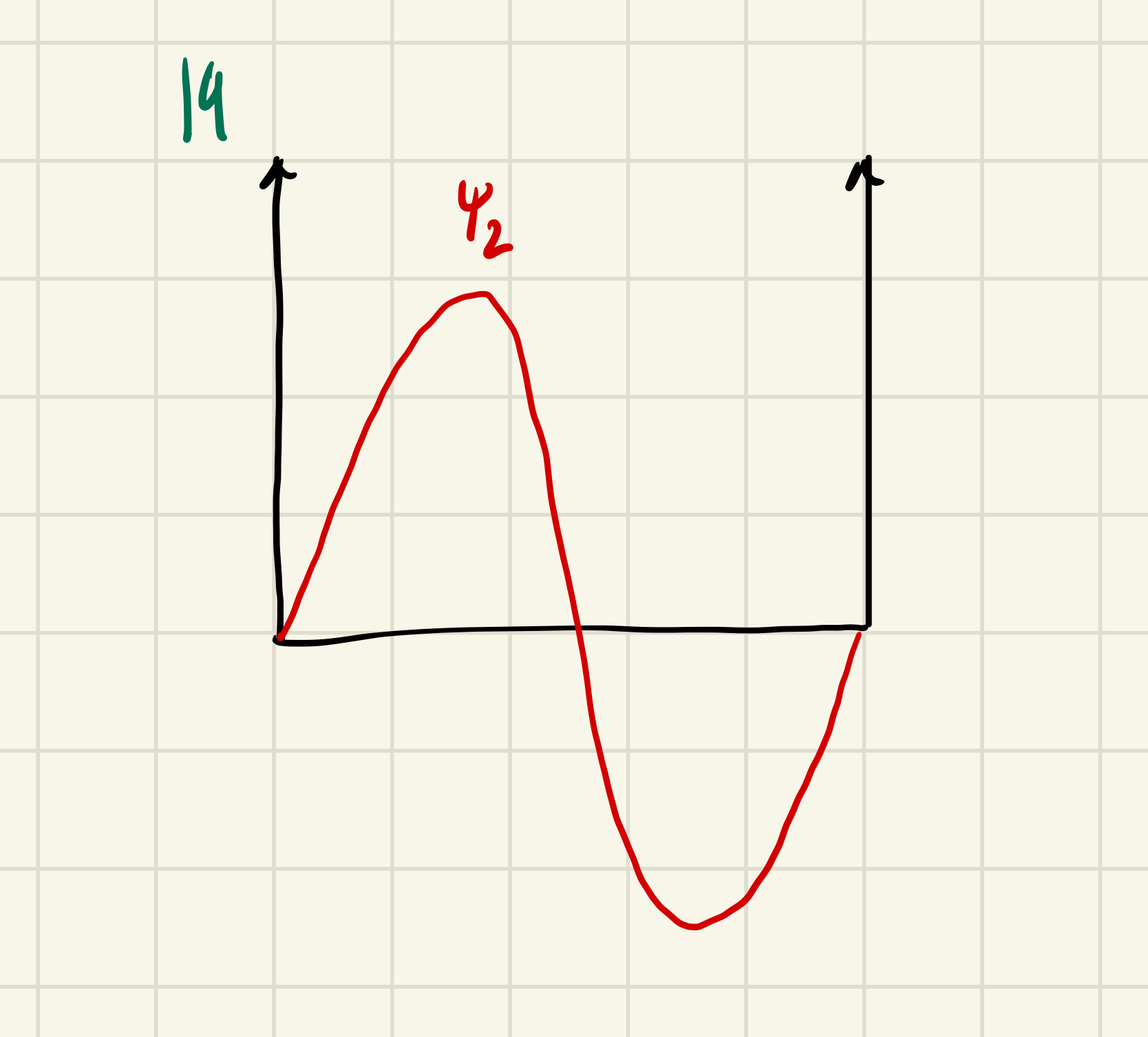

Particle in a (1-dimensional) box

aka particle confined to a line segment

FIGURE 3

What is V(x)?

Cannot exist outside of box

V(x) outside the box = ∞ → no amount of energy will allow the particle to escape

Only exists inside the box → no preference for location, consistent energy in all areas of the box

V(x) = 0 → can be any real value but 0 is convenient

FIGURE 4

General Solution:

d/dx sin k x = k cos k x

d/dx(k cos k)=k² sin k x

let k² = 2mE/ħ²

General solution: A sin k x + B cos k x

Verify: d²/dx² [Asinkx+Bcoskx]

= d/dx[kAcoskx - kBsinkx]

=-k²Asinkx-k²Bcoskx]

=-k²[Asinkx+Bcoskx]

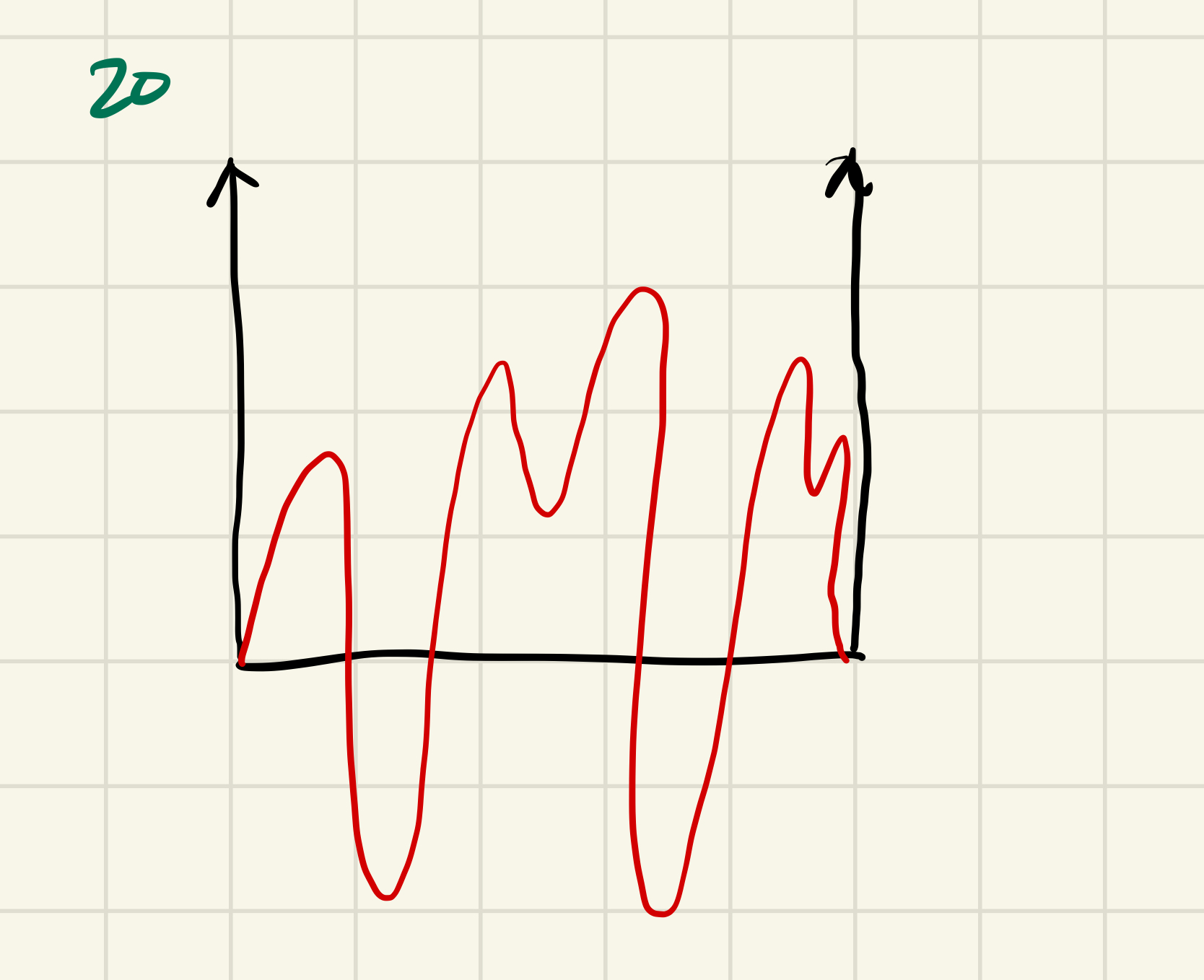

Impose Boundary Conditions

Wave function has to become zero at points on box x=0 and x=L

Conditions:

ψ(x) =. Asinkx+Bcoskx

ψ(0) = 0

ψ(0)= Asink(0) + Bcosk(0) = 0

B = 0 → removes cos term

ψ(L) = 0

ψ(0)= Asink(L) = 0

kL = 0, π , 2π, 3π → nπ, where n=integer

n=quantum number

kL=nπ → k = nπ/L

previous k value → sqrt(2mE/ħ) = nπ/L

E = n²π²ħ²/2mL²

PIB Solutions:

ψ(n) = A sin (nπx/L), En = n²π²ħ²/2mL² ← general solutions, A sin (nπx/L) is Asin(kx) substituted

n=1, A sin (πx/L), En = π²ħ²/2mL²

FIGURE 5

FIGURE 6

1/30 - PIB solution + spectroscopy model

FIG 7

Recall that ψ² tells you the probability of finding a particle at x. Since particles have to be found somewhere, the total sum of probabilities must =1

Normalization condition : ∫|ψ(x) |² dx =1

for PIB:

∫[0,L] A²sin² (nπx/L) dx = 1

A² ∫[0,L] sin² (nπx/L) dx = 1

cos2x=1-2sin²x → sin²x = ½ - cos2x/2

A² ∫[0,L] [1/2-1/2(cos(2nπx/L)))]

A² [1/2x - L/4nπ sin(2nπx/L)] ∫[0,L]L = 1

A² [L/2 - 0]-[0-0]]

A² [L/2] = 1

A=sqrt (2/L)

Eigenstate → physical interpretation

Eigenfunction → mathematical representation

Draw the n=1 eigenstate for a quantum mechanical particle confined to move along a line segment

FIG 8

Where are you most likely to find the particle? How do you know?

L/2, the highest value on the graph

How much energy would I need to add to the system to move the particle into the n=2 state?

FIG 9

h²/8mL²

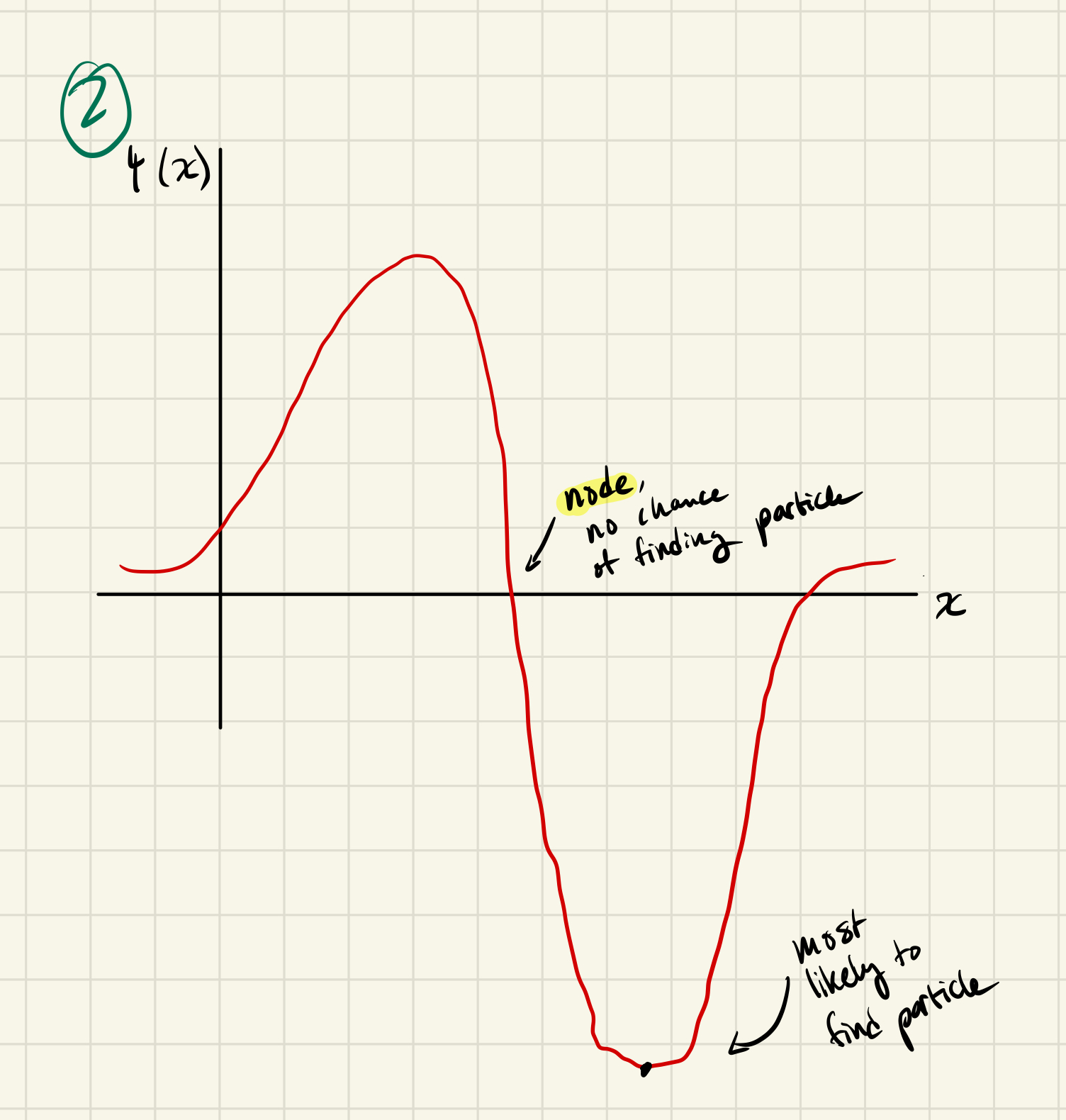

Now suppose that the particle is in the n=2 eigenstate. At what points are you most likely to find the particle?

L/4, 3L/4

What is the probability of finding the particle right in the middle of the box now?

The middle is a node, so = 0

Does the particle have a well-defined postion? Does it have a well-defined energy?

The particle does not have a well-defined position. It does have a well-defined energy

What does it mean to say that a wave function is normalized? Why must a wave function be normalized?

Probability of finding particle needs to = 1.

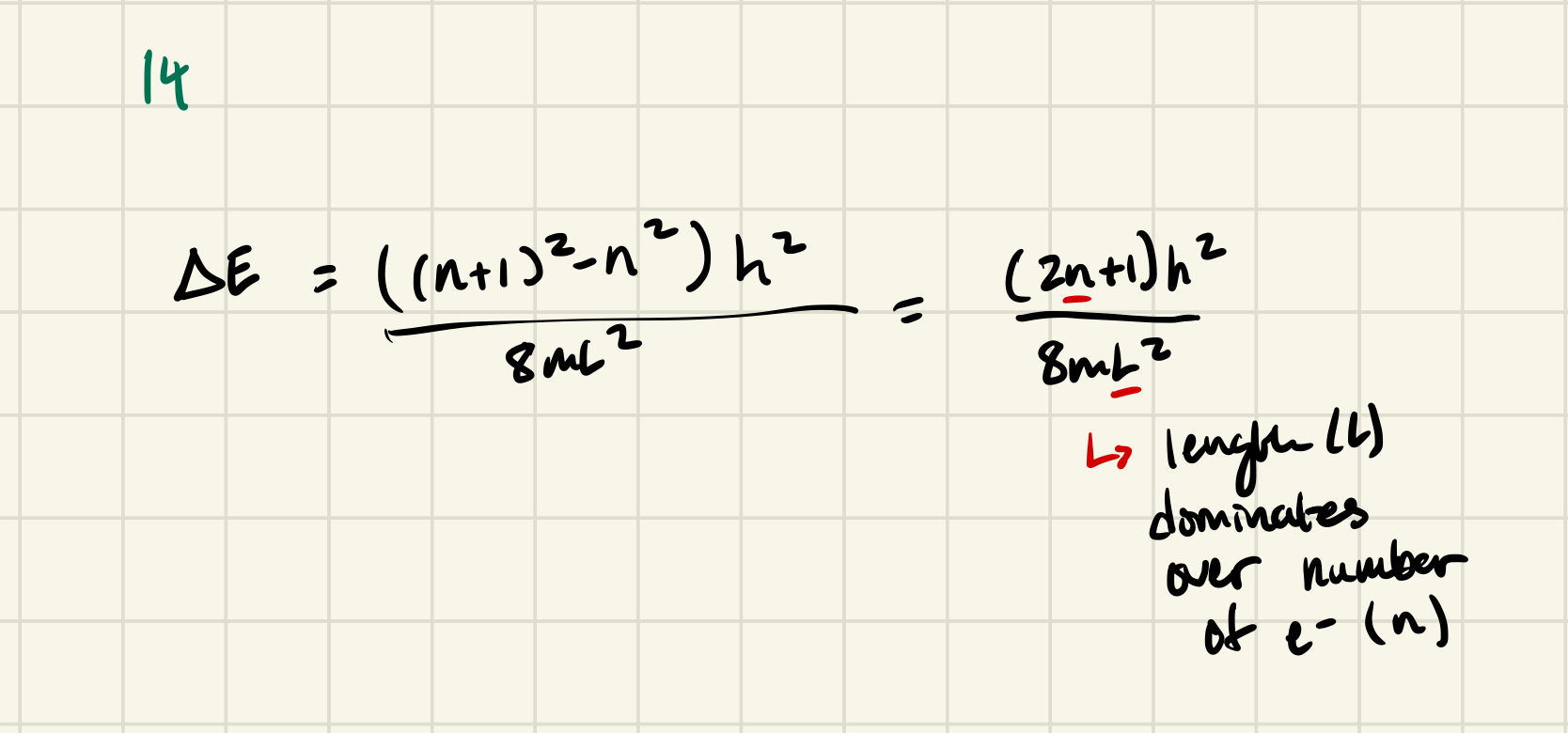

What would happen to the energy spacings for the particle in a box eigenstates if:

The box were made wider?

The energy spacing would be smaller → L is in denominator, if L is big enough, the energy spacing become continuous → less constraint

The mass of the particle were increased?

The energy spacing would be smaller → mass is in denominator

Expectation (or average) value

FIG 10

All PIB article states are liquid serum

Expectation value (for what when) <x> average position

By symmetry , <x>, /s

1,2,3,4,5,6

= 1/6(1)+2\1/6(2) + (1/6)3…..

Weighted die (50% of a 1, 10% of each 2-6

1/2×1 + 1/10×2 + 1/10 × 3….

Weighted average

sum of values i Pi (i)

<x>= F |psi(x)|² ] ∫ ψ(x)*x*ψ(x) dx

∫0 to L xsin² (n(pi)x/L) dx

Calculate the expectation value of the position <x> and momentum <p> for the n=1 eigenstate of a PIB: Do your answers make sense? Would <x> and <p> be for any other eigenstate of PIB?

<x> = F |psi(x)|² ] ∫ ψ(x)*x*ψ(x) dx

<p> = 0 for all PIB eigenstates

F psi(x)*phat*psi(x)dx = F sqrt(2/L sin (n(pi)x/L) (-ihbar*d/dx) sqrt(2/L(npix)) = 0

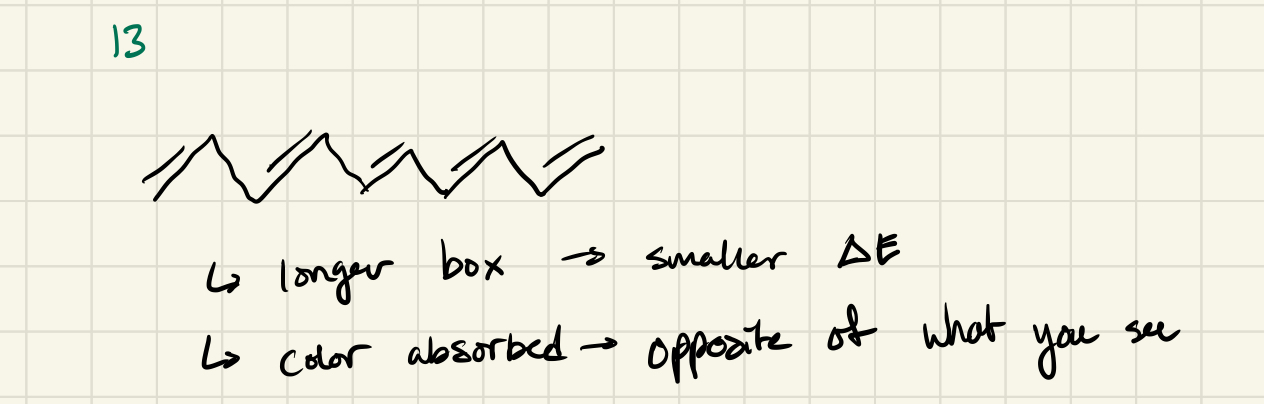

PIB as a (coarse) model for real things

e- in conjugated pi systems (ie benzene)

E- within metals (conduction) (not discussed in this class)

In conjugated pi systems

delocalized/spread out (like a wave) across molecule

Why is the model coarse/approximate?

Ignores nuclear attraction

e- can actually leave the molecule IRL

Ignores all the other e-

Delta E for n=3 orbital = (3² - 2²)*h²/8mL²

delta E = h * frequency

n=1 ground state

n=2 HOMO

n=3 LUMO

2/3 - Spectroscopy + Wave Function

As a model for spectroscopy

HOMO n=2

LUMO n=3

IMAGE 12

Energy = (3² - 2²) h²/8mL²

Less constrained = more classical E/ wavelength

Wave Functions

The four time-independent postulates:

All information about a quantum mechanical system is contained in the wave function

non-deterministic behavior → particle movement is inherently unpredictable (also don’t know position for position/velocity)

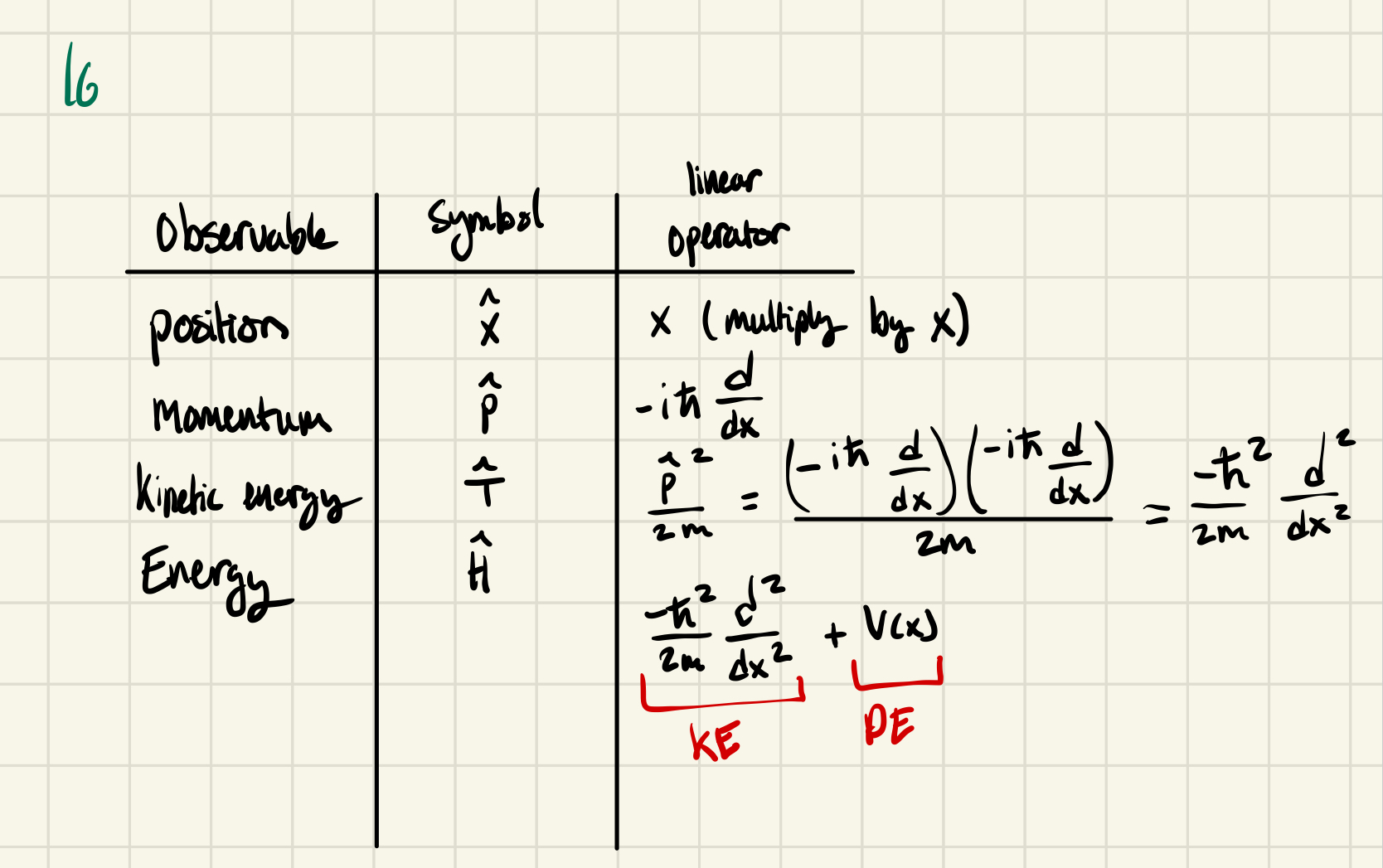

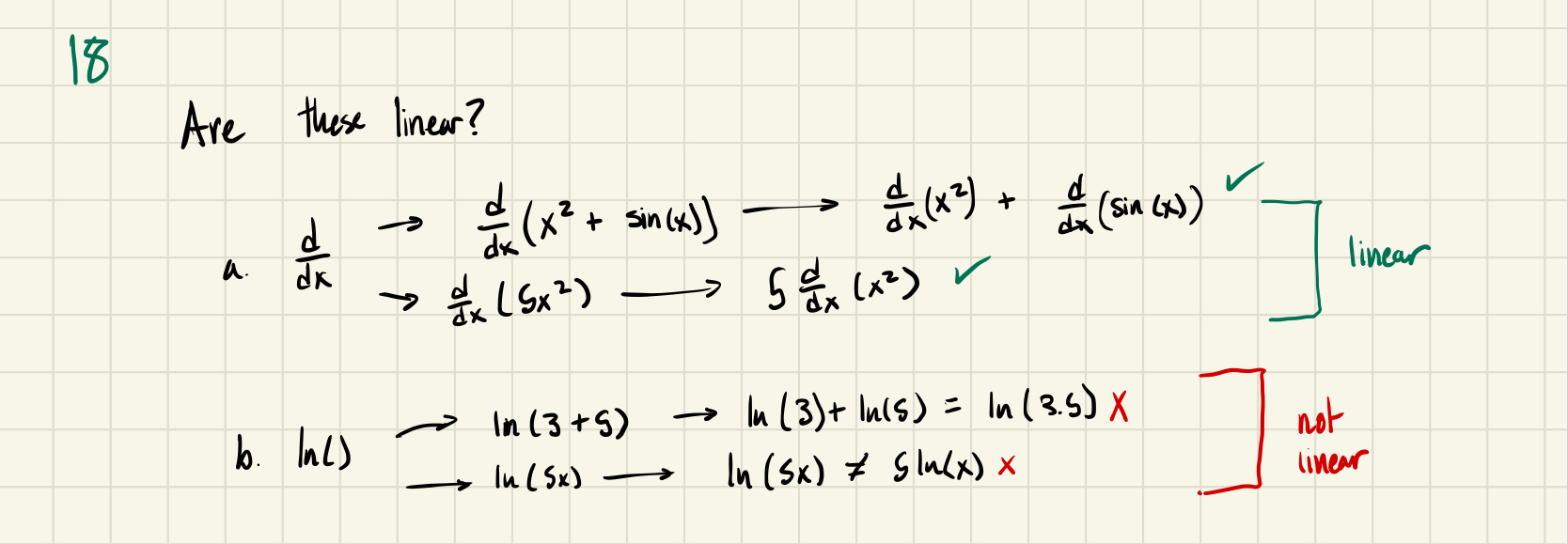

To every observable in classical mechanics, there corresponds a linear operator in quantum mechanics

Observable → a property or characteristic

Linear if:

Satisfies the distributive property aka: Â(f1(x)+f2(x)) = Âf1(x) = Âf2(x)

Can remove constant and operator aka: Â(cf(x)) = cÂ(f(x))

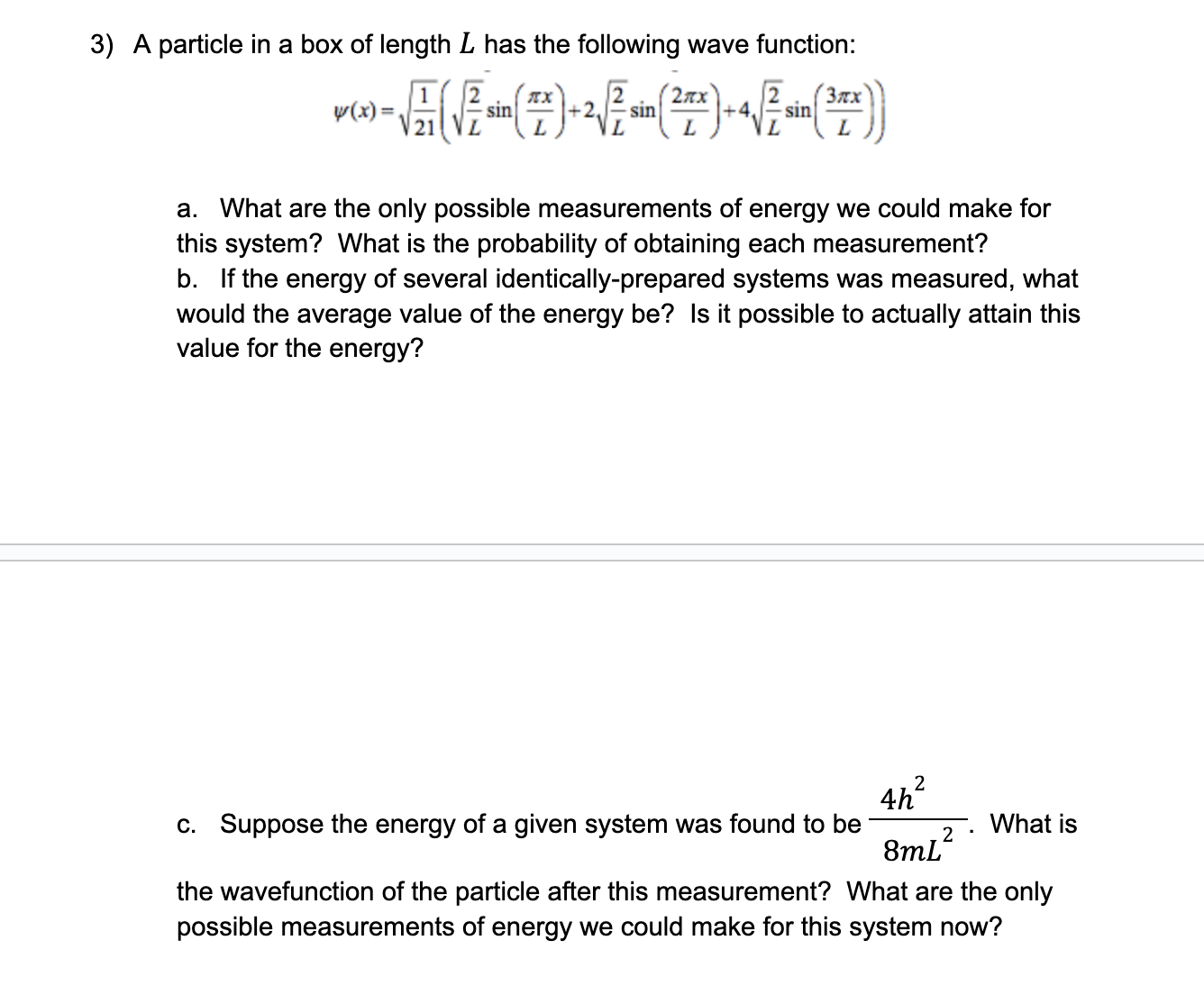

In any measurement of the observable associated with operator Â, the only values that will ever be measured are eigenvalues of the operator Â

ÂΨa = aΨa → where a is the eigenvalue

Example: Suppose I have a PIB. The only values I can get for the energy (E) are 1h²/8mL² ; 4h²/8mL² ; 9h²/8mL² ; 16h²/8mL² → these are the only allowed quantized energies

Suppose the particle is in an eigenstate of Â. (Â = Ĥ in this example)

Ψ(x) matches the Ψn = sqrt(2/L sin (nπx/L))

What happens if I measure E? → I will get E2 with 100% certainty. The particle has a well-defined energy. The particle matches an existing defined eigenstate.

Suppose the particle is not in an eigenstate of Â. (Â = Ĥ in this example)

Ψ(x) does not match the Ψn = sqrt(2/L sin (nπx/L))

ÂΨ(x) =/= EΨ(x)

The particle does not have a well-defined energy. It does not match an existing eigenstate.

Must still get an eigenvalue from a measurement, but unsure which one (E=2? 4?)

Suppose I get E2 → after the measurement, Ψ(x) “collapses” and becomes Ψ(2) → Copenhagen interpretation

Now energy is defined. Remeasurements will always result in Ψ(2)

2/5 - 3rd/4th postulate of QM

Any function can be written as a weighted sum of eigenstates

IMAGE 22

aka Fourrier series

Probability of measuring En = Cn² → aka (weight)²

the higher the weight, the better the probability of measuring that energy

A weighted sum of states is called a “superposition of eigenstates” → it has both energy levels at the same time

Example

Does the particle above have a well-defined energy?

No, you cannot pull out an eigenvalue so the energy is not well-defined

IMAGE 23/24

ImG 25 → Can swtich between defining position and energy, but not both

IMG 26

Postulate 4:

For any observable with operator Â, the average value (or expectation value) of the observable for a wavefunction Ψ(x) is:

IMG 27

Orthogonality

“independent” or “have no overlap”

For vectors, “perpendicular” is used

Orthogonality is the same concept, but applied more generally

IMG 28

For any given operator in quantum mechanics, all its eigenfunction are mutually orthogonal

Functions do not contain any other functions within them, they are not dependent on them

2/6 - Orthogonality + New Model: Vibrations

<E> = integral (psi* ˆH psi dx)

New model: Vibrations of a chemical bond

2/10 - Vibrations model

V(r ) → V(x) = 1/2 kx²

X=0 → at equillibrium bond length

X>0 stretched bond

X<0 compressed bond

2/12 - Spectroscopy

2/18 - Vibrational-Rotational (Microwave) Spectroscopy

Rigid rotor- model for rotation of molecules

slower than vibrations

can be excited → moves faster

2/19 - Rigid Rotor + Rotational-Vibrational IR Spec

2/20 - Hydrogen Atoms

So far:

PIB (exact) (models electrons)

Harmonic oscillator (exact) (models nuclei)

rigid rotor (exact) (models whole molecules)

hydrogen atom (models electron)

Hydrogen:

1 proton (nucleus) +1

1 electron -1

Assume proton is fixed at the origin

Electrostatic attraction b/t proton and electron → distance b/t is ‘r’

V( r ) = (-e²)/(4πε0r)← coulomb’s law - potential energy b/t two things is V= k*q1*q2/r1,2

Proton charge : 1.6 ×10^-19 C = +e

Electron charge: -e

K=1/(4πε0)

ε0 = permittivity of free space

H^ for hydrogen

-(hbar)²/2(mass of electron) * [ 1/r² (partial derivative) (r² Partial derivative) + (1/r² sin (theta)) (partial derivative of theta) sin theta (partial derivative of theta)) +(1/r² sin (theta) second partial derivative of phi)] + (-e²/4πε0r) psi (r, theta, phi) = E psi r, theta, phi

Laplacian + V( r ) = E(psi)(r, theta, phi)

3D problem → 3 quantum numbers (psi n,l,m(l))

=Rnl(r ) U(superscrpt ml) (subscript m) (theta, phi) ← radial function, spherical harmonic

Can be solved exactly