Agriculture

]]The British Agricultural Revolution]]

]]The British Agricultural Revolution, or Second Agricultural Revolution, was an unprecedented increase in agricultural production in Britain arising from increases in labour and land productivity between the mid-17th and late 19th centuries. This increase in the food supply contributed to the rapid growth of population in England and Wales, from 5. 5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by 1801, though domestic production gave way increasingly to food imports in the nineteenth century as the population more than tripled to over 35 million. [1] Using 1700 as a base year (=100), agricultural output per agricultural worker in Britain steadily increased from about 50 in 1500, to around 65 in 1550, to 90 in 1600, to over 100 by 1650, to over 150 by 1750, rapidly increasing to over 250 by 1850.]]

]][2] The rise in productivity accelerated the decline of the agricultural share of the labour force, adding to the urban workforce on which industrialization depended: the Agricultural Revolution has therefore been cited as a cause of the Industrial Revolution. E. Mingay states that there were a "profusion of agricultural revolutions, one for two centuries before 1650, another emphasising the century after 1650, a third for the period 1750–1780, and a fourth for the middle decades of the nineteenth century". [3] This has led more recent historians to argue that any general statements about "the Agricultural Revolution" are difficult to sustain.]]

]][4][5] One important change in farming methods was the move in crop rotation to turnips and clover in place of fallow. .]]

]]The British Agricultural Revolution was the result of the complex interaction of social, economic and farming technological changes. Major developments and innovations include:]]

- ]]Norfolk four-course crop rotation: Fodder crops, particularly turnips and clover, replaced leaving the land fallow.]]

- ]]The Dutch improved the Chinese plough so that it could be pulled with fewer oxen or horses.]]

- ]]Enclosure: the removal of common rights to establish exclusive ownership of land]]

- ]]Development of a national market free of tariffs, tolls and customs barriers]]

- ]]Transportation infrastructures, such as improved roads, canals, and later, railways]]

- ]]Land conversion, land drains and reclamation]]

- ]]Increase in farm size]]

- ]]Selective breeding]]

]]Crop Rotation]]

]]One of the most important innovations of the British Agricultural Revolution was the development of the Norfolk four-course rotation, which greatly increased crop and livestock yields by improving soil fertility and reducing fallow. Rotation can also improve soil structure and fertility by alternating deep-rooted and shallow-rooted plants. During the Middle Ages, the open field system had initially used a two-field crop rotation system where one field was left fallow or turned into pasture for a time to try to recover some of its plant nutrients. Later they employed a three-year, three field crop rotation routine, with a different crop in each of two fields, e.]]

]]Oats, rye, wheat, and barley with the second field growing a legume like peas or beans, and the third field fallow. Over the following two centuries, the regular planting of legumes such as peas and beans in the fields that were previously fallow slowly restored the fertility of some croplands. Because nitrogen builds up slowly over time in pasture, ploughing up pasture and planting grains resulted in high yields for a few years.]]

]]The farmers in Flanders (in parts of France and current day Belgium) discovered a still more effective four-field crop rotation system, using turnips and clover (a legume) as forage crops to replace the three-year crop rotation fallow year. The four-field rotation system allowed farmers to restore soil fertility and restore some of the plant nutrients removed with the crops. Fallow land was about 20% of the arable area in England in 1700 before turnips and clover were extensively grown in the 1830s. Guano and nitrates from South America were introduced in the mid-19th century and fallow steadily declined to reach only about 4% in 1900.]]

]]Ideally, wheat, barley, turnips and clover would be planted in that order in each field in successive years. The clover made excellent pasture and hay fields as well as green manure when it was ploughed under after one or two years. The addition of clover and turnips allowed more animals to be kept through the winter, which in turn produced more milk, cheese, meat and manure, which maintained soil fertility.]]

]]The Dutch and Rotherham Swing]]

]]The Dutch acquired the iron-tipped, curved mouldboard, adjustable depth plough from the Chinese in the early 17th century. British improvements included Joseph Foljambe`s cast iron plough (patented 1730), which combined an earlier Dutch design with a number of innovations. Its fittings and coulter were made of iron and the mouldboard and share were covered with an iron plate, making it easier to pull and more controllable than previous ploughs.]]

]]New Crops]]

]]The Columbian exchange brought many new crops to different areas of the world, the most prominent was the potato. On top of this, potatoes had higher nutritive value than wheat, could be grown in even fallow and nutrient-poor soil, did not require any special tools, and were considered fairly appetizing. The 1740 famines buttressed their case. The mid 18th century was marked by rapid adoption of the potato by various European countries, especially in central Europe, as various wheat famines demonstrated its value. The potato was grown in Ireland, a property of the English crown and common source of food exports, since the early 17th century and quickly spread so that by the 18th century it had been firmly established as a staple food.]]

]]It spread to England shortly after it popped up in Ireland, first being widely cultivated in Lancashire and around London, and by the mid-18th century it was esteemed and common. Maize also had far higher per-acre productivity than wheat (about two and a half times), grew at widely differing altitudes and in a variety of soils (though warmer climates were preferred), and unlike wheat it could be harvested in successive years from the same plot of land. It was often grown alongside potatoes, as maize plants required wide spacing.]]

]]Enclosure]]

]]As early as the 12th century, some fields in England tilled under the open field system were enclosed into individually owned fields. The Black Death from 1348 onward accelerated the break-up of the feudal system in England. Many farms were bought by yeomen who enclosed their property and improved their use of the land. The process of enclosing property accelerated in the 15th and 16th centuries.]]

]]The more productive enclosed farms meant that fewer farmers were needed to work the same land, leaving many villagers without land and grazing rights. Some practices of enclosure were denounced by the Church, and legislation was drawn up against it; but the large, enclosed fields were needed for the gains in agricultural productivity from the 16th to 18th centuries. The process of enclosure was largely complete by the end of the 18th century.]]

]]Development of national market]]

]]Regional markets were widespread by 1500 with about 800 locations in Britain. The most important development between the 16th century and the mid-19th century was the development of private marketing. By the 19th century, marketing was nationwide and the vast majority of agricultural production was for market rather than for the farmer and his family. The 16th-century market radius was about 10 miles, which could support a town of 10,000.]]

]]The next stage of development was trading between markets, requiring merchants, credit and forward sales, knowledge of markets and pricing and of supply and demand in different markets. Eventually, the market evolved into a national one driven by London and other growing cities. By 1700, there was a national market for wheat.]]

]]Legislation regulating middlemen required registration, addressed weights and measures, fixing of prices and collection of tolls by the government. Market regulations were eased in 1663 when people were allowed some self-regulation to hold inventory, but it was forbidden to withhold commodities from the market in an effort to increase prices. In the late 18th century, the idea of self-regulation was gaining acceptance.]]

]]The lack of internal tariffs, customs barriers and feudal tolls made Britain "the largest coherent market in Europe".]]

]]Transportation Infrastructures]]

]]High wagon transportation costs made it uneconomical to ship commodities very far outside the market radius by road, generally limiting shipment to less than 20 or 30 miles to market or to a navigable waterway. In the early 19th century it cost as much to transport a ton of freight 32 miles by wagon over an unimproved road as it did to ship it 3000 miles across the Atlantic. A horse could pull at most one ton of freight on a Macadam road, which was multi-layer stone covered and crowned, with side drainage.]]

]]Land conversion, drainage and reclamation]]

]]It is estimated that the amount of arable land in Britain grew by 10–30% through these land conversions. Due to the large and dense population of Flanders and Holland, farmers there were forced to take maximum advantage of every bit of usable land; the country had become a pioneer in canal building, soil restoration and maintenance, soil drainage, and land reclamation technology.]]

]]Rise in domestic farmers]]

]]With the development of regional markets and eventually a national market, aided by improved transportation infrastructures, farmers were no longer dependent on their local market and were less subject to having to sell at low prices into an oversupplied local market and not being able to sell their surpluses to distant localities that were experiencing shortages. To be successful, farmers had to become effective managers who incorporated the latest farming innovations in order to be low cost producers.]]

]]Human Capital Effects]]

]]During the 18th century, a high share of farmers had the ability to basic numerical skills as well as the ability to read and write (literacy), both of which are skills that were far from widespread in the early modern period. There is a strong link between nutritional deprivation and cognitive abilities, therefore it seems likely that farmers were one of the groups of society that contributed significantly to the numeracy revolution achieved in Europe during the early modern era.]]

]]Selective Breeding of Livestock]]

]]In England, Robert Bakewell and Thomas Coke introduced selective breeding as a scientific practice, mating together two animals with particularly desirable characteristics, and also using inbreeding or the mating of close relatives, such as father and daughter, or brother and sister, to stabilise certain qualities in order to reduce genetic diversity in desirable animal programmes from the mid-18th century. Arguably, Bakewell`s most important breeding program was with sheep. Previously, cattle were first and foremost kept for pulling ploughs as oxen or for dairy uses, with beef from surplus males as an additional bonus, but he crossed long-horned heifers and a Westmoreland bull to eventually create the Dishley Longhorn.]]

]]British Agriculture from 1800-1900]]

]]Massive sodium nitrate (NaNO3) deposits found in the Atacama Desert, Chile, were brought under British financiers like John Thomas North and imports were started. Mining coprolite and processing it for fertiliser soon developed into a major industry—the first commercial fertiliser. Higher yield per acre crops were also planted as potatoes went from about 300,000 acres in 1800 to about 400,000 acres in 1850 with a further increase to about 500,000 in 1900. Labour productivity slowly increased at about 0.]]

]]6% per year. With more capital invested, more organic and inorganic fertilisers, and better crop yields increased the food grown at about 0. 5%/year—not enough to keep up with population growth. These laws were only removed in 1846 after the onset of the Great Irish Famine in which a potato blight[58] ruined most of the Irish potato crop and brought famine to the Irish people from 1846 to 1850.]]

]]Though the blight also struck Scotland, Wales, England, and much of Continental Europe, its effect there was far less severe since potatoes constituted a much smaller percentage of the diet than in Ireland. Hundreds of thousands died in the famine and millions more emigrated to England, Wales, Scotland, Canada, Australia, Europe, and the United States, reducing the population from about 8. 5 million in 1845 to 4. 3 million by 1921.]]

]]Between 1873 and 1879 British agriculture suffered from wet summers that damaged grain crops. The development of the steam ship and the development of extensive railway networks in Britain and in the United States allowed U. S. farmers with much larger and more productive farms to export hard grain to Britain at a price that undercut the British farmers.]]

]]At the same time, large amounts of cheap corned beef started to arrive from Argentina, and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the development of refrigerator ships (reefers) in about 1880 opened the British market to cheap meat and wool from Australia, New Zealand, and Argentina. It hit the agricultural sector hard and was the most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fuelled by the Second Industrial Revolution in the decade following the American Civil War. By 1900, half the meat eaten in Britain came from abroad and tropical fruits such as bananas were also being imported on the new refrigerator ships.]]

]]Seed Planting]]

]]Before the introduction of the seed drill, the common practice was to plant seeds by broadcasting (evenly throwing) them across the ground by hand on the prepared soil and then lightly harrowing the soil to cover the seed. Seeds left on top of the ground were eaten by birds, insects, and mice. Tull`s seed drill was very expensive and fragile and therefore did not have much of an impact. [62] The technology to manufacture affordable and reliable machinery, including agricultural machinery, improved dramatically in the last half of the 19th century.]]

<<The Columbian Exchange<<

<<The Columbian exchange is a term coined by Alfred Crosby Jr. in 1972 that is traditionally defined as the transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the Old World of Europe and Africa and the New World of the Americas. The exchange began in the aftermath of Christopher Columbus` voyages in 1492, later accelerating with the European colonization of the Americas.<<

<<Apart from occasional contact with Vikings in eastern Canada 500 years prior to Columbus and Polynesian voyages to the Pacific Ocean coastline of South America around 1200, there was no regular or substantial contact between the world`s peoples. By the 1400s, due to rising tension in the Middle East, Europeans began the search for new trade routes led by Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (1394-1460), who sailed southward along the west coast of Africa, establishing trading posts. 1451-1506), sailing under the flag of Spain on behalf of Ferdinand II of Aragon and his wife Isabella of Castile, proceeded westward across the Atlantic Ocean in search of direct routes with the same markets in Asia. Columbus and his ships departed Spain on 3 August 1492, making a brief stop in the Canary Islands for provisions and ship repairs, before commencing the 5-week voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.<<

<<Following Columbus' first journey, the Spanish, and later other Europeans, began settlements in which they attempted to recreate their Old World lifestyles and cultures in the Americas.<<

<<Plants<<

<<The crops brought to the Americas by the Europeans in the late 1400s and early 1500s served to satisfy European demands to recreate their traditional diets but would also disrupt New World agricultural systems. In time, additional cereals and sugar would cross the Atlantic, allowing Europeans to create large agricultural plantations first in the Caribbean and later spreading to Mexico and throughout the rest of the Americas. Africa supplied not only people for work but contributed to the exchange of plants by introducing rice, bananas, plantains, lemons, and black-eyed peas, creating additional sources of food and wealth for colonists and agricultural enterprises.<<

<<The Americas also provided Europe, Asia, and Africa with a rich variety of new foodstuffs. Maize, potatoes, beans, tomatoes, peanuts, tobacco, and cacao (chocolate) were among the plants that journeyed eastward across the Atlantic. By the 1530s, tobacco, smoked and inhaled (in the form of snuff) by Native Americans, became a very valuable cash crop, especially in the British Middle Atlantic colonies. The cacao bean was ground into a powder and infused into water creating a very bitter drink, which was disliked by Europeans.<<

<<The Spanish added sugar and honey to alleviate the bitterness, and in the next hundred years, as it spread throughout Europe, vanilla was added to the mixture producing a new luxury item: chocolate. The discovery and use of quinine by Europeans assisted them in their future colonial adventures in Africa. Arriving in Europe after 1493, capsicum spread throughout South and East Asia and was adopted into the traditional cuisines of many European and Asian countries including Hungary (paprika) and Korea (kimchi). Tobacco, initially thought to possess medicinal value, was used in the American colonies as a currency for a short while.<<

<<Thought to increase creativity and reduce hunger, coca is the central ingredient in producing cocaine. Native to the Andes, coca was chewed as part of a ritual in the Inca religion and was adopted as such by Spanish settlers in the New World.<<

<<Animals<<

<<The Columbian Exchange facilitated the transfer of all of the major domesticated animals from the Old World to the Americas: cattle, horses, sheep, goats, and pigs. The largest animal present in the Americas was the bison, but it resisted domestication. The Spanish allowed imported domesticated herds to roam freely over the plentiful supply of lands upon which the animals thrived. Three domesticated European animals had an immediate effect: cattle, horses, and pigs.<<

<<The horse allowed Europeans to travel greater distances into the interior of the continents. The horse also provided greater speed and height advantages in conflicts with the indigenous peoples and frightened the natives with their appearance. Unable to contain the proliferation of reproduction, the horse spread quickly across the Americas. On his second voyage to the Americas in 1493, Columbus brought pigs.<<

<<Unusually rugged in surviving the ocean voyage, the pig provided the Spanish with an additional source of food.<<

<<Diseases<<

<<Native populations were decimated by disease outbreaks which allowed the Spanish, and later Europeans, to conquer the indigenous populations more easily.<<

<<Having been cut off from exposure to diseases after the last Ice Age, the native peoples lost any acquired immunities. Additionally, the indigenous population of the Americas had fewer domesticated animals from which diseases might emerge and transfer. Indigenous peoples would begin to sicken and die in extremely high numbers so much so that by 1650 it has been estimated that 90% of the native populations perished. Disease was the most effective ally of the Spanish conquistadors either preceding or accompanying them in their conquests across the Caribbean and the Americas.<<

<<Hernan Cortés, in August 1519, successfully conquered the largest city in the Americas, Tenochtitlan, after a 75-day siege in which a few hundred conquistadors defeated a native army numbering in the thousands.<<

<<Syphilis crossed the Atlantic Ocean back to Europe by some of Columbus` sailors who had engaged in sexual relations with native women in the Caribbean. A few of those sailors joined the army of Charles VIII of France (r. Recently historians have offered an alternative theory about the introduction of syphilis into Europe.<<

<<Consequences<<

<<Often referred to as one of the most pivotal events in world history, the Columbian exchange altered life on 3 separate continents. The new plants and animals brought to the Americas and the new plants brought back to Europe transformed farming and human diets. From the 16th century onward, farmers enjoyed a wider variety of plants and animals to choose from to earn a living and expand their prospects for wealth. The Transatlantic Slave Trade represented the largest forced migration of people in human history with the transfer of 12-20 million Africans to the Americas between the 16th to 19th centuries.<<

<<The result of the various exchanges became known as the triangular trade in which the Americas supplied the Old World with raw materials, Europe transformed those raw materials into finished goods which were traded to Africa and the Americas, while Africa supplied slaves to fulfill labor needs in the New World. The transfer of domesticated animals to the New World would, along with the transfer of plants, alter human diets, provide new forms of transportation and inaugurate a new form of warfare between peoples for centuries to come. Scholarship on the Columbian exchange has expanded to include additional items transferred across the ocean in the centuries after Columbus. The Columbian exchange, which started out as the introduction of new plants, animals, and diseases into different cultures, ultimately took on greater significance in the profound cultural, colonial, economic, nationalist, and labor consequences.<<

Hunting and Gathering

Before the invention of agriculture, humans obtained food they needed through, hunting, fishing, and gathering plants. Hunters and Gatherers lived in small groups. They traveled frequently. Today very few people still survive by hunting and gathering.

Agricultural Hearths

Southwest Asia

- The earliest crops were domesticated in Southwest Asia, these included barley, wheat, lentil, and olive.

- Southwest Asia was the largest hearth for animals that were the most prominent in agriculture including cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep.

East Asia

- Rice was developed in East Asia.

Central and South Asia

- Chickens were diffused from South Asia.

The horse was domesticated in Central Asia.

Sub-Saharan Africa

- Sorghum was domesticated in central Africa.

- Yams may have domesticated there.

- Millet and Rice have also been domesticated there independent of East Asia.

Latin America

- Mexico was a hearth for beans and cotton.

- Peru was the hearth for potatoes.

- Corn also emerged in Mexico and Peru independently.

The Green Revolution

The Green revolution included 2 main practices which were the introduction of new higher-yield seeds and expanded use of fertilizers. Normal Burlaug created a revolutionary type of wheat that could be grown throughout Mexico. It was resistant to stem rust.

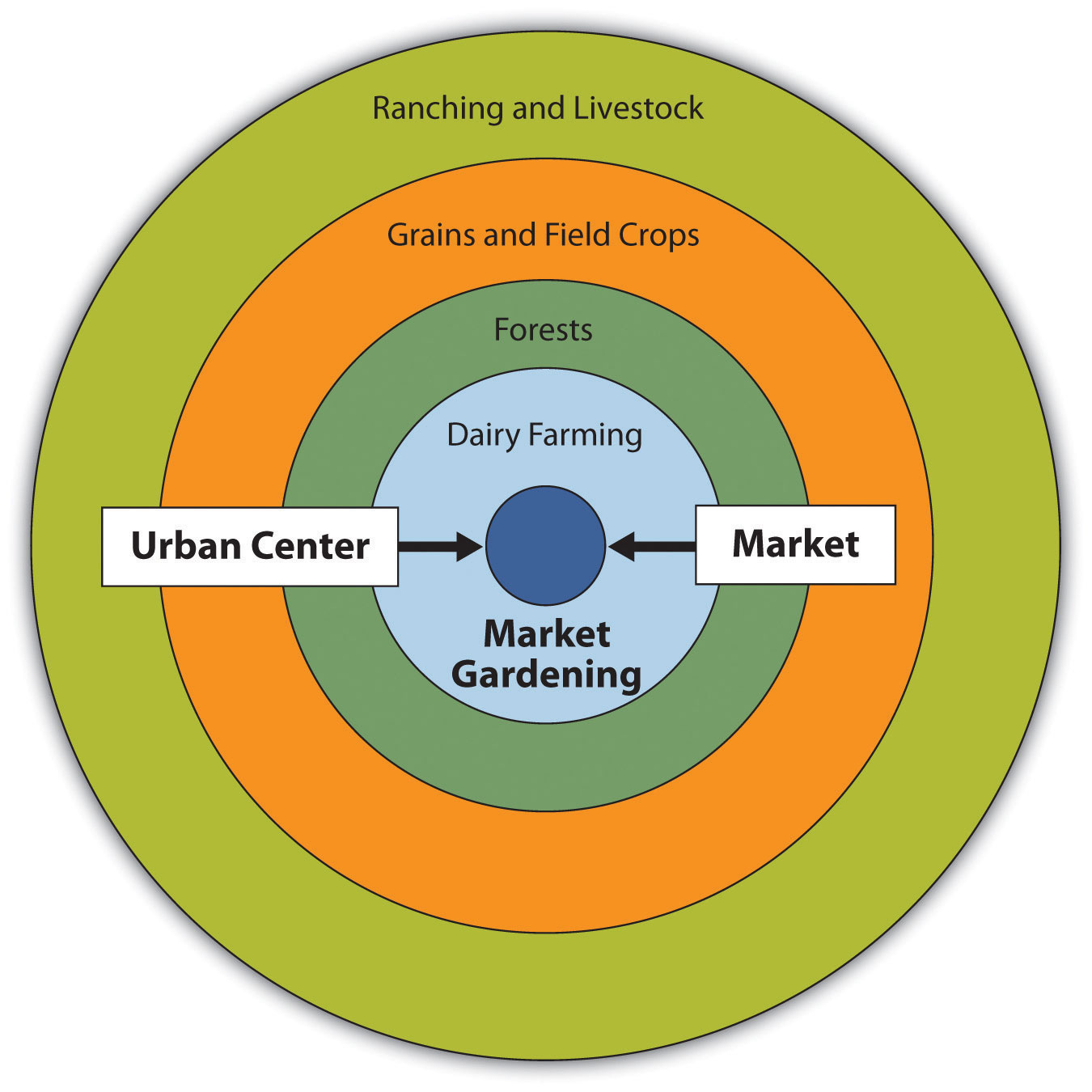

Van Thunen’s model

Thunen believed crops being produced in certain areas but not others came down to cost of land and transportation.

Ring 1- Dairy Farming

- intensive farming occurs in the ring closest to the city

- products that are perishable and expensive to transport are closer to the urban center/city.

Ring 2- Forest

- wood is used for fuels and materials

- Wood is heavy and difficult to transport

- In order to make profit you have to minimize transportation costs

Ring 3- Grains and Field Crops

- Grains can be stored, easy to transport, and lasts longer than dairy

- Requires a lot of land

Ring 4- Ranching and Livestock

- Animals need land to graze on

- Animals can be raised far from the city because they are self transporting

- land is cheap

Wilderness- No profit can be made

Does his model still apply to modern agriculture and society?

For the most part yet, things have changed though. We have changed how we produce food, globalization caused markets to be connected, culture has shifted(people have different tastes), as well as new crops have been introduced. These things have caused slightly off versions of his model in real world situations.

Bid Rent Theory

Scarcity affects land price and value. Price increases the closer you get to an urban area. Agriculture that uses less land can be closer to the market, and agriculture that uses a lot of land should be far away from urban centers.