Contracts Outline

Section I: Parol (or Extrinsic Evidence)

Definition of Parol Evidence

Parol evidence refers to any written or oral statements that are made prior to or at the same time as a final written agreement but are not included in that final agreement. This legal concept is crucial because it establishes the boundary of what outside information can be considered when interpreting a written contract.

When Do Parol Evidence Issues Arise?

Parol evidence issues typically arise in situations where two parties have documented their agreement in writing. This issue commonly surfaces during litigation when one party seeks to present extrinsic evidence to modify or clarify the terms of the existing written agreement. Understanding when parol evidence can be introduced is essential for the effective argument in cases of contract disputes.

Issue Spotting

Scenarios Indicating Issue Spotting for the Parol Evidence Rule (PER):

Existence of Written Evidence: Two parties entered into a contract and there exists a writing evidencing the K (if the contract was made orally, there is no PER issue).

Completion of Terms: One party claims that the writing includes all terms of the agreement, removing any uncertainty regarding what was agreed upon.

Contradictory Claims on Oral Agreements: The other party argues that there was an oral agreement or an additional written document that includes different terms from the written contract.

What is the Parol Evidence Rule?

The Parol Evidence Rule serves to limit the extent to which extrinsic evidence can be introduced to alter or contradict the terms of a written contract.

Total Integration: When the parties have completed their agreement in a written document, which they intend to serve as the complete and final integration of their agreement, any evidence of prior or contemporaneous agreements conflicting with that writing is inadmissible.

Partial Integration: In instances where the writing only partially integrates the agreement (confirming some, but not all terms), such a writing may not be contradicted but may be supplemented by evidence of consistent additional terms.

Policy Purpose of the PER

The primary purpose of the Parol Evidence Rule is to protect the integrity of written contracts, shielding them from the influence of unreliable or perjured testimony concerning oral terms that were not included in the writing. The rule encourages parties to commit their agreements to writing, thereby reducing ambiguity and the potential for disputes.

3 Step Analytical Framework

1. Determine Integration

What is Integration? Integration refers to the written material that the involved parties intend to adopt as their final expression of agreement regarding the terms it enunciates.

Types of Integration: There are three distinct types of integration: Total, Partial, or None.

Total Integration: The writing is considered FINAL and COMPLETE. No omitted terms exist in the agreement.

Parol Evidence Rule: The rule applies when parol evidence is inadmissible to challenge or supplement a complete integration unless specified exceptions apply.

Partial Integration: The writing constitutes a final expression regarding certain terms but not all agreed terms.

Rule Implications: Parol evidence contradicting a fully integrated document is inadmissible unless exceptions are made; however, consistent additional terms may be admitted.

No Integration: If the parties create a document that they do not consider final, then there is NO INTEGRATION.

Rule Implications: In this case, ALL extrinsic evidence is admissible.

2. Determine Admissibility of Evidence

Contradictory Term: This is a term that directly conflicts with the writing. For example, a term such as 'this agreement is irrevocable' may contradict a clause stating 'this agreement is revocable under certain conditions.'

Consistent Additional Term: A term that does not contradict the written agreement; it may provide further detail or clarification.

Test for Terms: Is it a term that could naturally be excluded from the writing?

Types of Integration and Their Rules:

Complete Integration: Neither contradictory nor consistent additional terms are admissible.

Partial Integration: Contradictory terms cannot be admitted, but consistent additional terms can be.

No Integration: Both contradictory and consistent additional terms can be introduced to the court.

3. Consider the Exceptions

Parol evidence may be admissible to demonstrate certain matters, such as:

The meaning of the writing, through the ambiguity exception. Evidence that is deemed necessary to explain ambiguous terms is always admissible. This is regarded as the principal exception to the PER.

Indications of fraud, duress, mistake, illegality, or lack of consideration; parol evidence may demonstrate the presence of these issues in a contract.

Oral conditions that precede the effectiveness of an agreement.

Subsequent oral or written agreements that occur after the drafting of the initial writing.

Collateral agreements with separate consideration since these are understood as independent agreements and not subject to the parol evidence provisions.

Case Illustration

Thompson v. Libby: This case exemplifies Williston’s classic “four corners” approach to parol evidence and contract integration, anchoring the legal principles accordingly.

Section II: Parol Evidence II UCC PER

Agreement vs. Contract

Contract Definition: The total legal obligation resulting from the parties' agreement as determined by the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) and supplemented by applicable law.

Agreement Definition: Refers to the actual bargain reached by the parties, as articulated in their language and inferred from related circumstances, including course of performance, course of dealing, or trade usage as per UCC 1-303.

Implication

The concept indicates that the parties’ complete agreement could encompass elements not expressly provided in the written document. To that end, extrinsic evidence from course of performance, course of dealing, and trade usage integrates into the broader agreement even when not explicitly stated in the written contract.

UCC 1-303

The UCC 1-303 delineates the definitions of Course of Performance, Course of Dealing, and Usage of Trade, outlining relevant considerations for contract interpretation. These definitions allow courts to account for how parties have acted historically and the prevailing industry standards, which assists in distilling the intent behind their agreement.

UCC Definitions

COP (Course of Performance): Refers to how the parties perform under the contract.

COD (Course of Dealing): Considers the conduct in the performance of prior contracts.

TU (Trade Usage): Identifies customs, practices, and methods regularly observed in a trade or industry, which justify parties’ reliance on them.

Hierarchy for Evidence

This hierarchy implies that even if a contract seems complete on its face, the necessity to understand underlying agreements may lead to examining external factors. This approach upholds the principle that contracts ought to be interpreted in a manner consistent with the expressed terms for evidence to be considered.

UCC 2-202 PER

Under UCC 2-202, written terms intended by parties as a final expression are shielded from being contradicted by prior agreements or contemporaneous oral agreements. However, these terms may be explained or expanded upon by:

Course of performance, course of dealing, or usage of trade.

Evidence of consistent additional terms may be accepted unless the court determines the writing to serve as a complete integration.

UCC 2-202 Analytical Framework

Determining Integration: The process remains consistent with common law approaches.

Determining Admissibility:

Evidence concerning Course of Performance, COD, and TU can be used for explanation or supplementation, even if a complete integration exists, differing from common law.

Evidence of consistent additional terms is typically permissible for explanation or supplementation unless the written contract is fully integrated.

Exceptions: Maintain the same considerations as in common law.

Section III: Interpretation

Definition and Guiding Principle

Interpretation of a contract is a frequent point of contention in legal disputes. This process involves determining what is meant when parties disagree about the meaning of terms included in their agreement, regardless of whether that agreement is in written form or otherwise.

Issue Spotting

For Interpretation Issues

Understanding the varying interpretations of a term between parties may highlight potential issues.

For Non-interpretation Issues

Conflicts over the terms of the agreement itself, rather than their meanings.

Analytical Framework for Interpretation

Determine Ambiguity (Textualist or Contextualist Approach): Ambiguity arises if the terms can reasonably be understood in multiple ways.

Resolve the Ambiguity:

Objective Standard: Focuses on how a reasonable individual would interpret the contract's intent.

Subjective Standard: Concentrates on the mutual knowledge of the parties regarding each other’s interpretations at the time of the agreement.

Consider Extrinsic Evidence; Apply the Rules of Interpretation:

Categories of Evidence Used to Interpret Meaning

Common interpretations of ordinary words.

Context regarding negotiations and related circumstances.

History of Course of Performance.

Patterns of Course of Dealing.

Usage of Trade applicable to the context.

Section IV: Implied Terms

Definition of Implied Term

An implied term is a stipulation that the law recognizes as being part of the parties’ agreement, even if it was not explicitly stated.

Rationale for Implied Term

Fairness: To ensure equitable treatment and outcomes.

Intent Representation: To capture the probable intent of the contracting parties.

Efficiency: To improve transactional outcomes and minimize disputes.

Implying Omitted Terms

Issue Spotting

Challenges arise when an agreement fails to address certain critical aspects related to the parties' dispute.

Rule

When a contract lacks clarity on essential terms, and the parties have sufficiently defined their agreement, the court can supply a reasonable term based on the circumstances.

Material Terms: If a term is not material, courts may fill in gaps.

Sufficient Performance: Courts typically will insert a reasonable term provided the parties have performed sufficiently.

Court Limitations: Courts will not fill gaps for material terms unless performance has been enough to invoke such a duty.

Case Illustration

Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon: Justice Cardozo's ruling reflects the implied obligation to exert reasonable efforts to fulfill the agreement regarding exclusive dealing.

Facts: In this case, Wood was granted the exclusive rights to place endorsements and market Lucy’s designs, with a profit-sharing arrangement. Lucy, however, began marketing through other channels.

Legal Implication: The court inferred an obligation for Wood to use reasonable efforts to advance the marketing of Lucy’s designs, emphasizing that even if such promise was not explicitly stated, it is fairly to be inferred from the nature of the contract.

Contemporary “Reasonable Efforts” and “Best Efforts” Clauses

Courts continue to recognize the implied duty for parties to utilize “best” or “reasonable efforts.”

UCC 2-306 “Best Efforts”

Contracts that stipulate dealing exclusively with another party’s goods imply a promise to use “best efforts” in distribution.

Exclusive Dealings Contracts (2 Kinds)

Output K: In this scenario, the buyer agrees to purchase all that the seller produces, with the stipulation that the seller cannot sell to anyone else.

Requirements Contract: Here, the seller commits to supply all items that the buyer requires, while the buyer agrees not to procure these items from other sellers.

UCC Art. II and Implied Terms

Certain UCC-imposed implied terms are mandatory and cannot be altered by mutual agreement, whereas others represent default rules which can be negotiated by either party.

Case Illustration

Leibel v. Raynor: This case illustrates the use of implied provisions surrounding reasonable notice of termination.

Legal Questions:

Does UCC Article 2 apply to this transaction?

Was Leibel entitled to a reasonable notice of termination with respect to the oral agreement?

Rule:

UCC 2-309 states that notice of termination is permitted at any time, but must meet the standard of being reasonable under the circumstances.

Section XI: Changed Circumstances:

Post K Formation, unforeseen events:

One of the parties is injured and can no longer perform the duties identified in the contract.

Stolen or destroyed property

Weather conditions

Natural disaster ◦

Government passes a law making the performance illegal

Changed Circumstances v. Mistake:

Changed Circumstances: address supervening unforeseen events AFTER K formation but BEFORE time for performance has become due. Basic assumption and allocation of risk.

Mistake: Mistake of fact by one or both parties at the time of K formation.

Basic assumption

Allocation of risk.

Terminology:

Impossibility: Performane of the agreement must literally be impossible to excuse performance.

Expired Approach: Strickt Liability for failure to perform regardless of any unforeseen supervening event

Modern Approach: Development of impossibility: Unforeseen, supervening events that occur before perforamne due but after K formation may excuse nonperformance.

Rest. 2d sec. 262,263 & UCC 2-613: Impossibility has been applied to K for personal services or the sale of specific unique goods (not fungible goods)

Where the particular person or thing “necessary for perforamne” dies or is incapacitated, is destroyed or damaged, impossibility may excuse performance:

Elements to excuse performance on impossibility a party must show:

An unforeseen, supervening event occurs after contract formation.

The non-occurrence of which is a basic assumption on which the K was made.

Which renders a party’s performance objectively (literally or physically) impossible.

Unless the K language or circumstances allocate risk of the event to one party.

Ex. National/ International emergency.

Governing law

governmental regulations or

The disruption of transportation, communication networks.

Impracticability: Performance must result in extreme and unreasonable difficulty, expense, injury, or loss to excuse performance.

Section 261: Where after a K is made a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault by the occurrence of an unforeseen event, the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which hteh contract was made, his duty to render that performance is discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate the contrary.

Elements of Impracticability:

An unforeseen ,supervening event occurs after K formation.

The non-occurrence of the event was a basic assumption on which teh K was made and

The event causes a party’s performance to become impracticable.

Exception: Unless teh K language or circumstances allocate the risk to one party.

Element 1: What does unforeseen event mean?: An unforeseen event that occurs after K formation but before performance is a major disruption.

Most courts ask whether teh external event was unforeseen, not contemplated by teh parties at the time of K formation, not whether the event was unforeseeable.

Element 2: What does basic assumption mean?: Parties must have assumed at the time of K formation that the external even would not hae occurred.

Like mistake doctrine, market conditions, financial situation of the parties are not basic assumptions that count.

Element 3: What does impracticable mean: One party cannot perform without severe loss or hardship, extreme and unreasonable difficulty, expense, injury or loss involved. BUT mere change in market conditions, financial situations of a party that makes K less profitable does NOT excuse performane.

Element 4 What does allocation of risk mean?: This is divided into steps.

Step 1: FORCE MAJEURE CLAUSES: Clauses that allocate risk of external events.

Step 2: If no force majeure, then courts ask: Copuld the party seeking excuse have controlled it in some way? Or did they?

Frustration of Purpose: When an unforeseen event undermines a party's primary purpose for entering thecontract and purpose becomes meaningless and is therefore excused:

Rule: Where after a contract is made a party’s principal purpose is substantially frustrated without his fault by the occurrence of an event, the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the hK was made, his remaining duties to render performance are discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate the contrary.

Frustration of Purpose Elements:

Supervening, unforeseen event

The nonoccurrence of which was a basic assumption of the K

Which substantially frustrates the principal purpose of the contract such that the value of the other party’s performance is nearly worthless to the party seeking excuse and

Exception: Unless the K language or circumstances allocate risk to one party.

Section XII: Modifying Common Law Contracts:

Rule: General Principles of K formation also apply to modifications:

Mutual Assent: (Offer & Acceptance)

Possible requirement of signed writing (SOF)

Consideration?

Traditional Rule: Modifications require independent consideration to be enforceable.

Based on a pre-existing legal duty

Rationale: Prevent Coerced medications

Modern Rule: a.k.a. the exceptions to the traditional common law rule:

Move away from requiring consideration in certain contexts.

Unforeseen circumstances

Statute

Reliance

Mutual release/ rescission

UCC ART. 2 Modification Rules:

Modification does not need consideration to be enforceable

But must be in GOOD FAITH

GF=HIF + observance of reasonable commercial standards of fair dealing in the trade.

SOF must be satisfied

If the contract as modified falls within the SOF then it must satisfy the SOF

Litigated issue: Courts disagree about how to apply 2-209.

N.O.M. Clauses: No oral modification clause:

A clause that expressly precludes contract modification except in writing.

IT IS A PRIVATE SOF! (won’t agree to K changes unless in writing.)

Rule: If a contract has no oral modification clause, then that clause will be enforced. However, there is a twist in how merchants use this form.

Where a merchant has supplied a form with a NOM clause to the other party, teh clause is enforceable only if:

OTHER party is a merchant OR

Other party has separately signed the NOM clause.

Waiving and retracting the waiver of an NOM clause:

Rule: Waiving the NOM clause: An attempt to orally modify that fails under 2-209(2) or 2-209(3) may still be a waiver.

Retracting the waiver: Once a party has waived the NOM clause by conduct they may retract the waiver by reasonable notice.

Unless retraction would be unjust due to the other party’s reliance.

Section XIII: Conditions:

Conditions as a Contracting Device:

What is a condition: An event that triggers a legal right or duty.

Mechanism that controls how the transaction unfolds (on-off switch).

Obligor: The party whose performance is triggered when the condition occurs.

Obligee: the one to whom the performance obligation is owed upon fulfillment of the condition.

Conditions v. Promises:

Condition Precedent: An event that must take place before a party’s duty to perform is triggered.

Condition Subsequent: An event that terminates the duty of a party to perform contractual duties.

Analytical Framework for Express Conditions:

Step 1: Did the parties intend to include an express condition in the K:

The basic test is the “intent of the parties”

Look for key signaling language “if” “unless” and “provided that”.

Then look for the course of performance, course of dealing, and trade usage.

If ambiguous, then the condition is likely a promise and not a condition.

Example:

the zoning commission to rezone the property for commercial use, Buyer shall purchase the property from Seller, subject to Buyer receiving financing from a bank.” 1. Which facts describe the promise?

2. Which facts describe the event that is the condition?

3. Is this a condition precedent or condition subsequent?

Step 2: Did the express condition occur?

If YES then the obligor’s duty to perform has been triggered and their nonperformance would be a breach.

Rules: The law insists on strict compliance with express conditions.

Substantial performance of an express condition will not trigger the obligor’s duty to perform.

Step 3: If not, has the condition been excused?

Rule: If the condition ahs not occurred then the obglior’s duty to perform is not triggered UNLESS the law excuses the condition by reason of:

Waiver: Consideration necessary if material

Estoppel: Detrimental reliance on promise to waive

Prevention: Wrongful hindrance by a party with the duty to perform.

Forfeiture: Avoidance of disproportionate forfeiture:

Rule: The non-occurrence of the condition is excused is enforcement of it would cause disproportionate forfeiture.

What is a forfeiture?: This means denial of compensation that results when the obligee loses the expected bargain after he has substantially relied on the expectation of the exchange.

Study tool summary of express conditions:

Express conditions must be strictly satisfied, substantial performance of express conditions is insufficient.

Non-occurrence of express conditions discharges the obligor’s duty to perform.

UNLESS failure of the conditions to occur is excused because of waiver, estoppel preventions, or forfeiture.

Constructive Conditions: Implied by teh court from the promises exchanged in the parties’ agreement

Legal fictions that courts create (hence constructive.)

These conditions are just promises.

How are they used?: Courts apply them to resolve who performs first when the K is silent about the sequence of performance.

Meaning: A party’s duty to perform is conditioned on the other performing.

Section XIV: Breach:

The Law of Breach:

What is a breach of K?: When the performance of a duty under a k is due, any (unjustifiable) non-performance is a breach.

Types of Breach:

Substantial Performance: Occurs when there are trivial, insignificant deficiencies in the quantity or quality of performance.

The non-breaching party may not suspend performance or terminate the K. They must still perform.

They may sue for monetary damages for any harm the partial breach causes.

Measure of damages: Ordinarily reflects the cost to remedy the defective performance.

Determining Substantial Performance: There is no mathematical formula or bright line rule for determining substantial performance.

Involves a materiality analysis and determining, using the multi- factor material breach test.

Immaterial/partial breach.

Non-breaching party must perform but can sue for monetary losses resulting from the breach.

Material Breach: Failure to perform a significant performance obligation.

How may the nonbreaching party react?: The nonbreaching party may suspend performance while giving the breaching party a reasonable amount of time to cure defective performance.

Determining Material Breach: Must conduct a materiality analysis.

Multi-factored line drawing exercise.

Does not immediately discharge breaching party’s duties.

Non-breaching party may:

Suspend performance

Provide notice and await cure for reasonable time

Seek monetary damages for losses

Determining Material Breach (vs. Substantial Performance):

Deprival of benefit.

Adequate compensation for injured party

Forfeiture to breaching party

Likelihood of cure

Good faith and fair dealing.

Notice & Cure: Injured party must be given NOTICE of MB and the Opportunity to Cure

Most written K include notice & cure provisions because most courts will require them anyway.

Failure to provide notice & cure opportunity may turn the non-breaching party into the breaching party.

Total Breach: An uncured material breach. A material breach becomes total when it is not reasonable to make the non-breaching party wait any longer or when a breaching party has failed to cure.

Rule to for determining whether the opportunity to cure has passed giving rise to a total breach:

Result of delay: Does the delay harm the non-breaching party’s ability to make substitute arrangements?

Is performance without delay important?

How may the non-breaching party react if there is a total breach?: Non-breaching party may withhold performance and consider her duties discharged.

Terminate K. and

Sue for damages.

Uncured Material breach. Non-breaching party may

Suspend performance

Terminate K.

Seek monetary damages for losses.

Section XV: UCC Law of Breach.

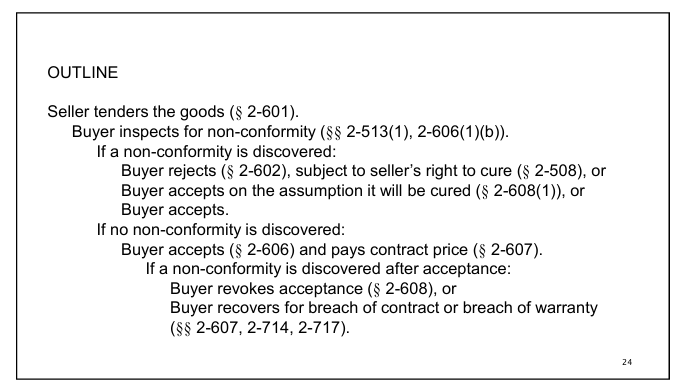

Sellers Nonperformance under Art. 2

Seller Performance: PRomises to sell, ship conforming goods according to the contract specs.

Buyers performance: Promises to accept conforming goods and pay for them according to the contract terms.

How might a Seller breach or repudiate the K:

Non-delivery of goods

Fails to make proper tender

Breach of Warranty

Anticipatory repudiation.

How might a buyer respond?:

Buyer rejects (perfect tender rule)

Rejections must occur within a reasonable time after delivery of goods

But seller might have cure rights.

Buyer Accepts:

Can seek warrant damages if non-conforming.

Buyer revokes Acceptance:

Must occur with reasonable time and before any substantial change in the condition of the goods occurs.

Cancellation:

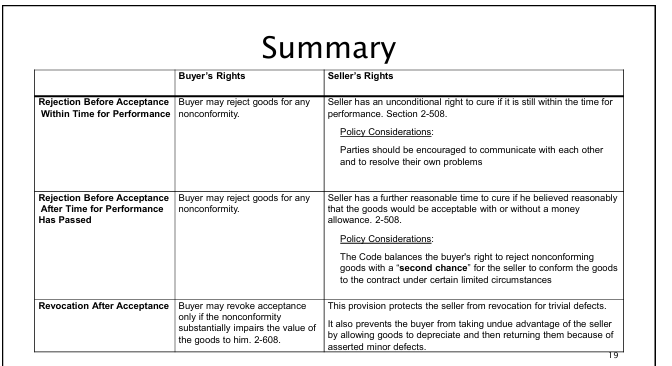

Buyer Can Reject Non-Conforming Tender:

Perfect Tender Rule: Seller must tender conforming goods.

Substantial performance is not enough. There must be perfect tender.

Only applies to contracts for the single sale. Installment K are governed by 2-612

Buyer’s Right to Reject:

Buyer has a right to reject nonconforming goods.

Rejection must occur within a reasonable time after delivery of the goods.

Buyer must seasonably notify the seller of the rejections.

Seller’s Cure Rights:

But Seller has the right to cure defective tender i.e. fix the problem.

Right to cure in two situations. . .

Time for performance remains or

Where the seller had reasonable grounds to believe the buyer would accept nonconforming goods.

Buyer can accept Nonconforming Tender:

The buyer can accept the goods, even if nonconforming

Acceptance occurs when the buyer:

After reasonable opportunity to inspect the goods and indicates to the seller she’ll keep them

Fails to reject but only after an inspection or

Takes action inconsistent with seller’s ownership.

Buyers Right to Inspect:

The buyer has the right to inspect before making payment before accepting or paying for them.

Except where K is for goods delivered

Buyer assumes costs of inspection unless goods are not conforming.

Buyer can accept & seek warranty Dx:

The buyer can accept the goods even if nonconforming

And seek damages for breach of warranty under 2-714.

Buyer Can Revoke Acceptance of Nonconforming Tender

Buyer may revoke acceptance:

Buyer may revoke acceptance of goods whose non-confomity substantially impairs their value to him if

Buyer accepted, reasonably assuming that seller would cure

Buyer accepted w/o discovering non-conformity due to difficulty of discover or seller assurances.

Timing: Revocation must occur within a reasonable time after buyer discovers grounds for revocations and before substantial change in condition of goods.

Buyer must seasonably notify seller of rejection.

Buyers NonPerformance:

Buyer’s primary obligation: Pay for any goods accepted when seller has tendered delivery of teh goods.

Buyer has rights before payment required:

Right to inspect goods

Right to reject non-conforming goods.

How might a buyer breach or repudiate?:

Fails to make payment.

Wrongful rejection of goods that are properly tendered.

Anticipatory repudiation.

Section XVI: Anticipatory Repudiation:

What is anticipatory repudiation?: Occurs when a party to a contract, before performance is due, indicates through words or actions that they will not perform their duties under the contract.

An “Advanced Breach.”

Rationale: Equivalent of total breach, provided that the threatened action or failure to act would be a material and total breach if it happened at the time due for performance.

Issue Spotting Anticipatory Repudiation: Looking for facts that suggest or indicate one party will not or may not perform when the time for performance becomes due.

Anticipatory Repudiation Analytical Framework:

Is there an anticipatory repudiation?:

Common Law Rule: A party anticipatorily repudiated a contract when before performance is due, they:

Make an unequivocal and definite statement that they will commit a total breach or

Engages in any voluntary conduct that renders that party unable to perform his duties.

Article 2: UCC Rule:

Words or Conduct indicating that a party will not perform and the loss of performance will substantially impair the value of the contract to the non-repudiating party.

Synthesized Rule for anticipatory repudiation: An anticipatory repudiation is a voluntary, clear and unequivocal statement or act that is serious enough to qualify as a total breach of the contract.

What is NOT an anticipatory repudiation?:

Good faith dispute

Suggestion or request to modify the contract is NOT a repudiation.

Showing hesitation, hedging

Financial insolvency of one party, standing alone is not enough to justify the other party declaring repudiation.

Buy may give the right to demand “adequate assurances.”

What are the rights of the non-repudiating party?:

Common Law Rule: After repudiation, the non-repudiating party may:

Suspend performance

Terminate the contract and sue for breach or

Continue to treat the contract as valid and wait for the time of performance before bringing suit.

UCC Rule: Injured Party may suspend performance and either:

Await performance for a commercially reasonable period to time, or

Assert breach and seek damages.

Has the repudiating party retracted his repudiation?

Common Law Rule: The repudiating party’s ability to retract the repudiation when the injured party:

Gives notice that it chooses to treat the contract as rescinded or terminated

Treats the anticipatory repudiation as a breach y suing or

Materially changes its position in reliance on the repudiation (no notice requirement).

UCC Rule:

When: Before the next performance due unless the aggrieved party has canceled or materially changed position.

How?: By any method that is clear to the aggrieved party, but must include assurances demanded.

Effect of retractions?: Reinstates repudiating party’s right under the contract.

Special Context: Reasonable grounds and adequate assurances: If one party has reasonable grounds for insecurity about the other party’s performance, they may request adequate assurance of future performance.

The insecure party may suspend performance until assurances are received.

Demand for Adequate Assurances Letter:

Practice Tip 1: Requires written demand but courts do not uniformly enforce that requirement

Practice Tip 1: Demand must clearly state the assurances are being requests and specify them.

Mere requests for information/meeting is not a demand.

UCC Reasonable Grounds for Insequrity and Adequate Assurances: Both defined by commercial rather than legal standards.

But there are not hard and fast rules look at:

Other party’s words/actions

Nature of teh K

Court of dealing

Course of Performance

Trade Usage.

Examples:

Significant financial difficulties, falling behind in payments

FAilure to perform important duties

Indirect communications

But not rumors or insignificant risks.

Adequate Assurances UCC:

Varies depending on the circumstances.

Demand should be proportional to the grounds for insecurity.

Don’t ask for more than adequate.

Common examples: Verbal Guarantees.

Time for Assurances:

Must provide necessary assurances within reasonable time not exceeding thirty days.

Failure to provide the assurances gives non-repudiating party the right to treat the contract as repudiated, terminate and seek damages.