W4: Development of wage labour in the modern economy

Long Cycles of Economic Growth and Capitalist Crisis

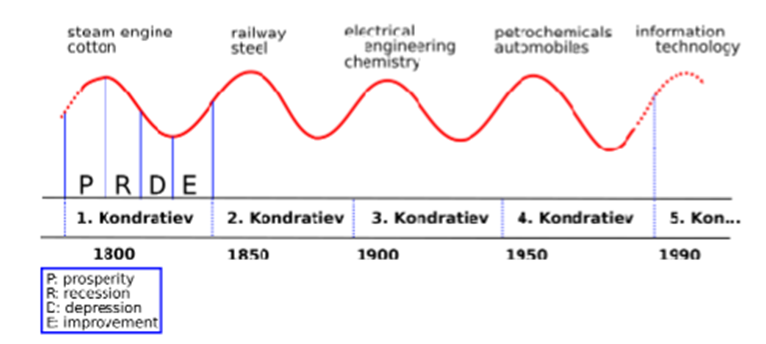

long swings/waves/cycles of capitalist development

socio-institutional underpinnings

Fundamentals of capitalist development

Economic growth process in capitalist economy riven by:

distributional conflict

fundamental uncertainty

Capitalism as “contested terrain”:

various forms of non-cooperative rivalry between:

individual firms (e.g. market competition)

aggregate “capitals” (e.g. industry and finance)

state and capital (e.g. control over social priorities)

capital and labouring (e.g. terms and conditions of work)

Decision making is contingent and takes place in historical time

“today is a break in time between an unknown future and an irrevocable past.” (Robinson, 1962, p. 26)

Social structure of accumulation (SSA) theory

Historical growth record is characterised by long-term fluctuations

long cycles of approx 50 years

intermediate term upswings and downswings

equilibrium punctuated by capitalist crises (i.e. persistent economic stagnation and/or stability)

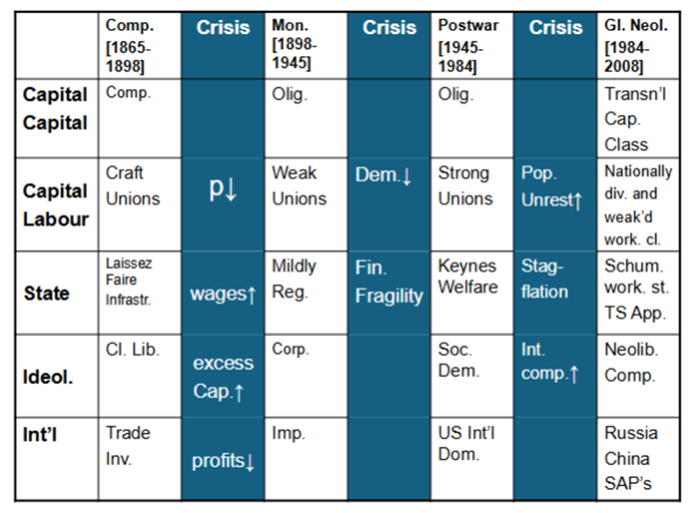

Explained by rise and decline of successive SSAs

an SSA is a mutually-consistent array of institutions

“institutions” are in/formal “rules of the game”

SSAs encompass economic, political and cultural institutions

SSAs underpin capitalist expectations of stable profitability

What are the potential contradictions which could end global neoliberalism?

insufficient aggregate demand

financial and monetary fragility

peak oil

environmental crises

The End of “the end of history”

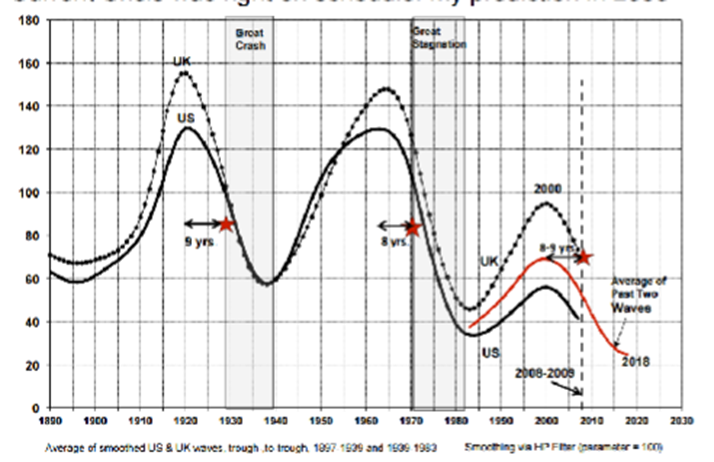

“Our findings suggest that a profit rate long wave is likely to last for about 40-45 years. According to this pattern, the current, neoliberal long wave has by now probably reached its peak, and will enter its declining phase… there is growing evidence suggesting that the current neoliberal global economy suffers form certain structural contradictions that would lead to major crisis in the coming years.” - Minqi Li et al., ‘Long Waves, Institutional Changes, and Historical trends’ (JWSR, 2007)

Current Crisis following 2003 prediction

Future

Globalised neoliberal capitalism remains mired in stagnation-financialisation trap

“a historical interregnum… morbid symptoms.”

Renewed interest in theories of “stages of capitalism” (McDonough, 2007, 2015)

SSA Theory

Regulation theory

Varieties of capitalism

World systems theory

Modern SSA Theory: an integral innovation in hetecon

Analytical tool:

“…making sense of much of economic history. It links theoretical analysis with concrete institutional investigation. It provides a basis for understanding the evolution of capitalism over time, as well as institutional differences among capitalist systems in different countries. Not the least, it provides a basis for explaining the periodic severe economic crises that have arisen in capitalist history.” - (Wolfson and Kotz, 2010)

Policy/political tool

“… sheds light on the possible future directions of restructuring, which is helpful for developing political strategy” - (Kotz, 2015)

State of the art

Since 2008 crisis:

refocus on capital labour relations and profitability

greater focus on capital-nature relations

increased diversity (authors, countries, theory, method)

tentative engagement w/ Social Reproduction Theory

“cultural turn” in political economy

incorporate technological revolutions

Indirect response to Jessop and Sum (2006)

SSA and the World System

Systemic cycles of accumulation (SCAs) and chaos in world system (Arrighi; Silver)

rise and fall of successive hegemonic imperial powers

Secular trends of world-historical capitalist development (Marx; Wallerstein)

tendency of rate of profit to fall

concentration and centralisation of capital

social-ecological devastation

financial crisis of world capitalism?

Feudalism, agricultural development and the rise of wage labour

Feudalism

Ownership of labour by feudal Lords labour service and military duty provided by the peasantry in return to land for subsistence farming and protection in times of scarcity.

Restriction of mobility of labour and limitation of skill development in agricultural societies. Concentration of wealth was for the immediate consumption of the feudal nobility and funding conflict between feudal nobles or foreign wars.

Mercantilism and the rise of trade

The development of trading empires in the 15th and 16th centuries giving rise to wealth and resources as well as taxation for the central state.

Coerced labour Indentured labour and chattel slavery

Slavery in the American south and capitalist agricultural production of cotton. The triangle trade between British exports of manufacturers to West Africa, exchanged for slaves who were then transported across the Atlantic and sold into slavery on plantations and the cotton on and tobacco produced in these plantations then was transported back across the Atlantic to British ports of London, Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow. Debates over this continue today.

Free wage labour

The development of labourers paid money wages for their services without access to capital and without recourse to agricultural land-based resources.

Feudalism in Europe

The development of class societies led by the 14th century to a series of different societies in which land holding was controlled by a class of lords, barons, clan chiefs across Europe in what becomes identified as feudalism.

Agricultural societies in which serfs were provided with small parcels of land to provide their own subsistence in exchange for a share of the output and labour duties provided on the feudal Lord’s land. This involved the need to provide military service, if necessary.

The success of feudalism was to revive towns and trading of metal works, newer technologies in the form of the plough, new techniques for the use of horses and the growth of agricultural output. Along with this came the need for the written word, paper, printing, accounting, international trade and consumption of luxury goods.

Much of this was already in existence in more advanced economies, including India, China, the Middle East and Africa. Western Europe was an economic backwater in the 13th and 14 centuries and the British Isles was the backwater of the backwater.

Within the next two to three hundred years Western Europe was to become the powerhouse of economic development and technological innovation and by the 1830s Britain was recognisably the most advanced economy in the world.

The main explanations arose for these transformations’ population change, technological change, urbanisation and trade and, finally changes in social relations. These became the focus of what became known as the Brenner debate. They also re-emerge in the debates around the reconstruction of the World Economy after WW2 from the 1950s and again around globalisation in the 21st century.

“Behind most economic trends in the middle ages, above all behind the advancing the retreating land settlement, it is possible to discern the inexorable effects of rising and declining population.” - M.M. Postan, Medieval economy and society: An economic history of Britain in the middle ages, p. 72.

A key outcome of the Brenner debate was its renewed focus on social causation. While participants sought a single explanation for economic change, this now seems misguided. Historians today recognize the complexity and geographic variation of historical processes. As Bois advises, broad theories shouldn't overshadow detailed research.

Crisis of Feudalism

By the period of the 17th Century a series of trading empires had emerged in Western Europe. Control over this trade was the centre of wars and conflict between the rising states. England, Spain, France and Portugal had all developed trading relationships with the far East and also the Americas. A trade in luxury goods, sugar, spice, tea and cocoa for making chocolate along with manufacturers of silk and cotton were now becoming subject to the creation of new markets in towns within these empires. Control over these trade routes and access to these markets were the subject of increasing tensions between empire states.

Rising urbanisation originating from land enclosures led to new social relations of wage labourers and the ‘middling sort’ skilled craft workers capable of developing manufacturing in metalworking, pottery, woodworking and other craft-based technologies.

Within rural communities’ agriculture continues to provide employment for large agricultural workforce, which itself was increasingly differentiated between traditional serfs, bound to the land undertaking subsistence farming and small scale peasant farmers who owned or leased land independently from barons and the nobility.

Conflict between where and who benefitted from the surpluses these feudal societies created with a growing proportion of unproductive feudal nobility, a declining peasantry and growing wages labourers in the countryside and towns.

Mercantilism

The development of trading empires led to the growing of wealth of merchants and traders. The impact of this trade was to ensure bullion, gold and silver was increasingly concentrated among the elites who controlled this trade as paid or by the physical movement of gold, silver or other valuable assets. Thus economies who had trade surpluses were able to build up stocks of gold and bullion. This could be used to pay for wars and expenditure. Forms of internal taxation - on markets and goods sold all generated opposition. Taxes on wealth holding alienated the landed gentry. Ordinary people could not have income taxes due to their low incomes. Therefore, trade provided a means to generate income for these early and developing nation states.

Alongside taxes on trade also provided protection for domestic production. Tariffs on imports protected manufacturers at home while providing funding for the state.

Whereas land was the origin of wealth within feudalism now wealth was derived from trading activities.

This did not go unchallenged intellectually. Adam Smith writing in the Wealth of Nations restates the importance of labour over land or trade in the creation of wealth:

“The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with the necessities and conveniences of life.” And “Labour is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities.”

He distinguishes between those engaged in productive activities giving rise to new wealth and those engaged in unproductive activities use up wealth created by others:

“The labour of some of the most respectful orders in the society is, like that of menial servants, unproductive of any value, and does not fix or realise itself in any permanent subject or vendible commodity, which endures after that labour is part, and for which an equal quantity of labour could afterward be procured. The sovereign, for example, with all the officers both of justice and war who serve under him, the whole army and navy, are unproductive labourers… They are… maintained out of the annual produce of other people…” - Adam Smith (Wealth of nations, p. 104/430-1)

As industrial production grew, the industrial revolution placed British manufacturing at the centre of global production calls for an end to tariffs also developed. Free trade over protectionism was a central idea of those who looked to the labour theory of value. It allowed for new markets for manufactured goods, lowered the costs of food stuffs - the campaign to end the tariffs on imported foodstuffs was understood to lower the cost of living for workers - and increased the importance of an understanding of an economy based upon labour power.

We therefore have here a three-way debate on the origins of wealth and value: deriving from land, labour or wage labour.

This is represented in the concept of factors of production in modern neo-classical economics:

land

labour

capital

This schematic representation of the strands of argument in the Brenner debate suggests competing casual diagrams:

population growth → economic activity → sustained economic growth (Postan)

weak peasant farmers, strong capitalist farmers → enclosure, the rise of wage labour and farming innovations → rapid agricultural growth (Brenner)

enhanced protections of property rights → incentive for profitable activity → sustained economic growth (North)

And later a fourth factor of production is introduced:

Entrepreneurship emphasising risk of individuals engaged in profit seeking activity through firms.