SOPH CHILD DEVE 2

Week 8 moral Develpment

WHAT IS MORAL DEVELOPMENT?

- MORAL DEVELOPMENT INVOLVES CHANGES IN THOUGHTS, FEELINGS, AND BEHAVIORS REGARDING STANDARDS OF RIGHT AND WRONG.

- THE INTRAPERSONAL DIMENSION PERTAINS TO A PERSON’S ACTIVITIES WHEN SHE OR HE IS NOT ENGAGED IN SOCIAL INTERACTION.

- THE INTERPERSONAL DIMENSION PERTAINS TO SOCIAL INTERACTIONS, INCLUDING COOPERATION AND CONFLICT.

WHAT IS MORAL DEVELOPMENT?

- TO UNDERSTAND MORAL DEVELOPMENT, WE NEED TO CONSIDER FIVE BASIC QUESTIONS:

- HOW DO CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS REASON, OR THINK, ABOUT RULES FOR ETHICAL CONDUCT?

- HOW DO CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS ACTUALLY BEHAVE IN MORAL CIRCUMSTANCES?

- HOW DO CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS FEEL ABOUT MORAL ISSUES?

- WHAT COMPRISES CHILDREN’S AND ADOLESCENTS’ PERSONALITY WITH RESPECT TO MORALITY?

- HOW IS THE MORAL DOMAIN DIFFERENT FROM SOCIAL CONVENTIONAL AND PERSONAL DOMAINS?

WHAT IS MORAL DEVELOPMENT?

- NOTE THAT IN SOCIAL - COGNITIVE DOMAIN THEORY ,

- CHEATING RESIDES IN THE MORAL DOMAIN, ALONG WITH LYING, STEALING, AND HARMING ANOTHER PERSON.

- BEHAVIORS SUCH AS CUTTING IN A LINE OR SPEAKING OUT OF TURN ARE INSTEAD IN THE SOCIAL CONVENTIONAL DOMAIN.

- CHOOSING FRIENDS IS IN THE PERSONAL DOMAIN.

MORAL THOUGHT: PIAGET’S THEORY

PIAGET CONCLUDED THAT CHILDREN GO THROUGH TWO DISTINCT STAGES OF MORAL DEVELOPMENT.

- FROM 4 TO 7 YEARS OF AGE, THEY DISPLAY HETERONOMOUS MORALITY — THEY THINK OF JUSTICE AND RULES AS UNCHANGEABLE, REMOVED FROM PEOPLE’S CONTROL.

- THEY BELIEVE IN IMMANENT JUSTICE: THAT IF A RULE IS BROKEN, PUNISHMENT WILL BE IMMEDIATE; A VIOLATION IS AUTOMATICALLY CONNECTED TO ITS PUNISHMENT.

- FROM 7 TO 10 YEARS, CHILDREN TRANSITION GRADUALLY INTO THE NEXT STAGE.

- FROM ABOUT 10 YEARS AND OLDER, CHILDREN SHOW AUTONOMOUS MORALITY — THEY ARE AWARE THAT RULES AND LAWS ARE CREATED BY PEOPLE, AND IN JUDGING ACTION, THEY CONSIDER BOTH INTENTIONS AND CONSEQUENCES.

- THEY RECOGNIZE PUNISHMENT OCCURS ONLY IF SOMEONE WITNESSES THE WRONGDOING, AND PUNISHMENT IS NOT INEVITABLE.

- CHILDREN’S THINKING BECOMES MORE SOPHISTICATED THROUGH THE GIVE - AND - TAKE OF PEER RELATIONS.

MORAL THOUGHT: PIAGET’S THEORY contoured by Thompson

- THOMPSON ARGUED YOUNG CHILDREN ARE NOT AS EGOCENTRIC AS PIAGET ENVISIONED.

- RESEARCH INDICATES YOUNG CHILDREN POSSESS COGNITIVE RESOURCES THAT ALLOW THEM TO BECOME AWARE OF OTHERS’ INTENTIONS AND KNOW WHEN SOMEONE VIOLATES A MORAL PROHIBITION.

- BECAUSE OF THEIR LIMITED SELF - CONTROL, SOCIAL UNDERSTANDING, AND COGNITIVE FLEXIBILITY, YOUNG CHILDREN’S MORAL ADVANCEMENTS ARE OFTEN INCONSISTENT AND VARY ACROSS SITUATIONS

MORAL THOUGHT: KOHLBERG’S THEORY

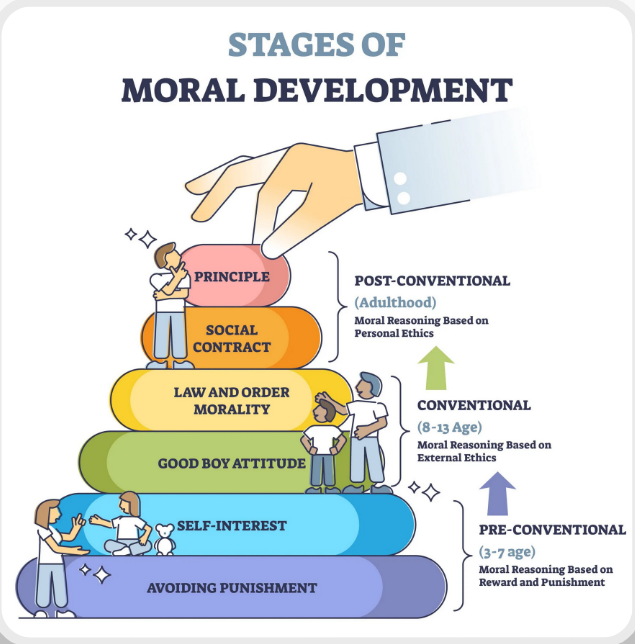

- KOHLBERG PROPOSED THREE LEVELS OF MORAL DEVELOPMENT.

- DEVELOPMENT FROM ONE LEVEL TO THE NEXT IS FOSTERED BY OPPORTUNITIES TO TAKE THE PERSPECTIVE OF OTHERS AND TO EXPERIENCE CONFLICT.

- KOHLBERG DEVELOPED STAGES IN THESE THREE LEVELS THROUGH INTERVIEWS IN WHICH CHILDREN ARE PRESENTED WITH A SERIES OF STORIES OF CHARACTERS FACED WITH MORAL DILEMMAS.

- HE NOTED THAT INTERACTION IS A CRITICAL PART OF THE SOCIAL STIMULATION THAT CHALLENGES CHILDREN TO CHANGE THEIR MORAL REASONING.

- if there is no conscience, they will not know the meaning of mistakes and effects of our actions

MORAL THOUGHT: KOHLBERG’S THEORY

- PRECONVENTIONAL REASONING: THE LOWEST LEVEL, AT WHICH GOOD AND BAD ARE INTERPRETED IN TERMS OF EXTERNAL REWARDS AND PUNISHMENTS.

- CONVENTIONAL REASONING: INTERMEDIATE LEVEL, AT WHICH INDIVIDUALS APPLY CERTAIN STANDARDS THAT ARE SET BY OTHERS, SUCH AS PARENTS OR GOVERNMENT.

- POSTCONVENTIONAL REASONING: THE INDIVIDUAL RECOGNIZES ALTERNATIVE MORAL COURSES, EXPLORES OPTIONS, AND THEN DECIDES ON A PERSONAL MORAL CODE.

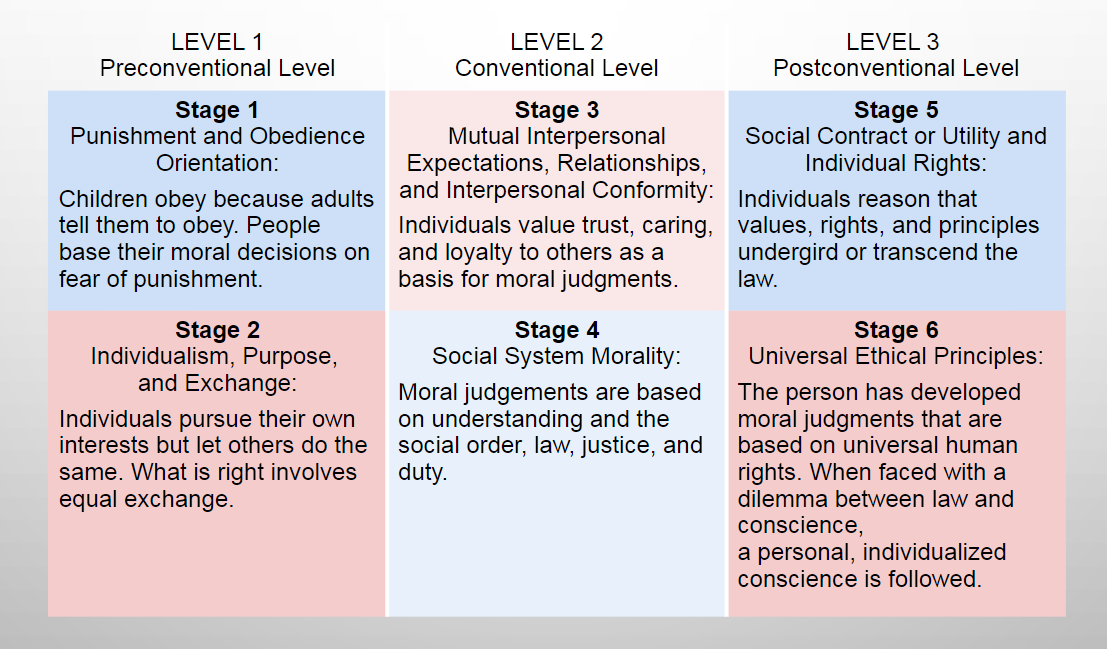

FIGURE 1 KOHLBERG’S THREE LEVELS AND SIX STAGES OF MORAL DEVELOPMENT

MORAL THOUGHT: KOHLBERG’S THEORY

- KOHLBERG’S LEVELS OCCUR SEQUENTIALLY AND ARE AGE - RELATED.

- BEFORE AGE 9, CHILDREN USE PRECONVENTIONAL REASONING.

- BY EARLY ADOLESCENCE, THEY REASON IN MORE CONVENTIONAL WAYS.

- BY EARLY ADULTHOOD, A SMALL NUMBER OF INDIVIDUALS REASON IN POSTCONVENTIONAL WAYS.

- THE MORAL STAGES HAVE BEEN FOUND TO APPEAR SOMEWHAT LATER THAN KOHLBERG INITIALLY ENVISIONED.

- REASONING AT THE HIGHER STAGES, ESPECIALLY 6, IS RARE.

- you cannot reason with a toddler

FIGURE 2 AGE AND THE PERCENTAGE OF INDIVIDUALS AT EACH KOHLBERG STAGE

- IN A CLASSIC LONGITUDINAL STUDY OF MALES FROM 10 TO 36 YEARS OF AGE, AT AGE 10 MOST MORAL REASONING WAS AT STAGE 2 (COLBY & OTHERS, 1983).

- AT 16 TO 18 YEARS OF AGE, STAGE 3 BECAME THE MOST FREQUENT TYPE OF MORAL REASONING

- IT WAS NOT UNTIL THE MID - TWENTIES THAT STAGE 4 BECAME THE MOST FREQUENT.

- STAGE 5 DID NOT APPEAR UNTIL 20 TO 22 YEARS OF AGE AND IT NEVER CHARACTERIZED MORE THAN 10 PERCENT OF THE INDIVIDUALS.

- IN THIS STUDY, THE MORAL STAGES APPEARED SOMEWHAT LATER THAN KOHLBERG ENVISIONED, AND STAGE 6 WAS ABSENT.

MORAL THOUGHT: KOHLBERG’S THEORY (5)

- MORAL REASONING AT EACH STAGE IS BASED ON THE INDIVIDUAL’S LEVEL OF COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT.

- KOHLBERG ARGUED THAT MORAL REASONING ALSO REFLECTS CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES WITH MORAL QUESTIONS AND MORAL CONFLICT.

- VIRTUALLY ANY PLUS - STAGE DISCUSSION SEEMS TO PROMOTE MORE ADVANCED MORAL REASONING.

- KOHLBERG STRESSED THAT IN PRINCIPLE, ENCOUNTERS WITH ANY PEERS CAN PRODUCE PERSPECTIVE – TAKING OPPORTUNITIES THAT MAY ADVANCE MORAL REASONING.

MORAL THOUGHT: KOHLBERG’S CRITICS

- SOME KEY CRITICISMS OF KOHLBERG’S THEORY:

- IT PLACES TOO MUCH EMPHASIS ON MORAL THOUGHT, AND NOT ENOUGH ON MORAL BEHAVIOR.

- CULTURE INFLUENCES MORAL DEVELOPMENT MORE THAN KOHLBERG THOUGHT.

- KOHLBERG SUGGESTS EMOTION HAS NEGATIVE EFFECTS ON MORAL REASONING, BUT EVIDENCE INDICATES EMOTIONS PLAY AN IMPORTANT ROLE.

- KOHLBERG SUGGESTS MORAL THINKING IS DELIBERATIVE; HAIDT SUGGESTS IT IS MORE OFTEN AN INTUITIVE REACTION.

- KOHLBERG PLACES TOO MUCH EMPHASIS ON PEER RELATIONS AND NOT ENOUGH ON FAMILY.

• THE MOST PUBLICIZED CRITICISM HAS COME FROM CAROL GILLIGAN:

- KOHLBERG’S THEORY IS BASED ON MALE NORMS THAT PUT ABSTRACT PRINCIPLES ABOVE RELATIONSHIPS AND CONCERN FOR OTHERS.

- THE HEART OF MORALITY IN HIS THEORY IS A JUSTICE PERSPECTIVE .

- A CARE PERSPECTIVE EMPHASIZES CONNECTEDNESS WITH OTHERS, INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION, SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS, AND CONCERN FOR OTHERS.

- GILLIGAN AND HER COLLEAGUES FOUND THAT GIRLS CONSISTENTLY INTERPRET MORAL DILEMMAS IN TERMS OF HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS.

- OTHER ANALYSES SUGGEST GIRLS USE BOTH MORAL ORIENTATIONS AS NEEDED — AS CAN BOYS.

MORAL BEHAVIOR

HE PROCESSES OF REINFORCEMENT, PUNISHMENT, AND IMITATION AFFECT HOW INDIVIDUALS LEARN MORAL BEHAVIOR.

- THE EFFECTIVENESS OF REWARD AND PUNISHMENT DEPENDS ON CONSISTENCY AND TIMING.

- THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MODELING DEPENDS ON THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MODEL AND THE COGNITIVE SKILLS OF THE OBSERVER.

BEHAVIOR IS SITUATIONALLY DEPENDENT.

- INDIVIDUALS DO NOT CONSISTENTLY DISPLAY MORAL BEHAVIOR IN DIFFERENT SITUATIONS.

MORAL BEHAVIOR: SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY

- THE SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY OF MORALITY EMPHASIZES A DISTINCTION BETWEEN MORAL COMPETENCIES AND MORAL PERFORMANCE.

- MORAL COMPETENCIES: WHAT INDIVIDUALS ARE CAPABLE OF, WHAT THEY KNOW, THEIR SKILLS, THEIR AWARENESS OF MORAL RULES AND REGULATIONS, AND THEIR COGNITIVE ABILITY TO CONSTRUCT BEHAVIORS.

- MORAL PERFORMANCE: ACTUAL BEHAVIOR, DETERMINED

BY MOTIVATION AND REWARDS AND INCENTIVES.- They may be in it for the money, what's there incentive or reward for it

- BANDURA HAS STRESSED THAT MORAL DEVELOPMENT IS BEST UNDERSTOOD AS A COMBINATION OF SOCIAL AND COGNITIVE FACTORS—ESPECIALLY THOSE INVOLVING SELF-CONTROL.

MORAL FEELING

- ACCORDING TO FREUD, GUILT AND THE DESIRE TO AVOID FEELING GUILTY ARE THE FOUNDATION OF MORAL BEHAVIOR.

- RESEARCHERS HAVE EXAMINED THE EXTENT TO WHICH CHILDREN FEEL GUILTY WHEN THEY MISBEHAVE.

- YOUNG CHILDREN ARE AWARE OF RIGHT AND WRONG.

- THEY HAVE THE CAPACITY TO SHOW EMPATHY AND PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR TOWARD OTHERS.

- THEY EXPERIENCE GUILT, INDICATE DISCOMFORT FOLLOWING A TRANSGRESSION, AND ARE SENSITIVE TO VIOLATING RULES.

MORAL FEELING: EMPATHY

- EMPATHY: REACTING TO ANOTHER’S FEELINGS WITH AN EMOTIONAL RESPONSE THAT IS SIMILAR TO THE OTHER’S FEELINGS.

- IT IS AN EMOTIONAL STATE BUT HAS A COGNITIVE COMPONENT—THE ABILITY OF PERSPECTIVE-TAKING, DISCERNING THE INNER PSYCHOLOGICAL STATES OF OTHERS.

- CHANGES IN EMPATHY TAKE PLACE IN EARLY INFANCY, AT 1 TO 2 YEARS OF AGE, IN EARLY CHILDHOOD, AND AT 10 TO 12.

FIGURE 3 DAMON’S DESCRIPTION OF DEVELOPMENTAL CHANGES IN EMPATHY

THE CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVE ON THE ROLE OF EMOTION IN MORAL DEVELOPMENT

- MANY CONTEMPORARY DEVELOPMENTALISTS BELIEVE BOTH POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE FEELINGS CONTRIBUTE TO CHILDREN’S MORAL

DEVELOPMENT.- WHEN STRONGLY EXPERIENCED, EMOTIONS INFLUENCE CHILDREN TO ACT IN ACCORD WITH STANDARDS OF RIGHT OR WRONG.

Add more slides from week 7

Families and Culture M3 W8

Family Processes

Consider Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory:

- Microsystem — the setting in which the individual lives.

- Mesosystem — links between microsystems.

- Exosystem — influences from another setting that the individual does not experience directly.

- Macrosystem — the culture in which the individual lives.

- Chronosystem — sociohistorical circumstances that change over time.

Every family is itself a system — a complex whole made up of interrelated and interacting parts.

Interactions in the Family System

- Synchrony in parent - child relationships is positively related to children’s social competence.

- Scaffolding, a form of synchrony, can be used to support children’s efforts at any age.

- Reciprocal socialization: bidirectional socialization.

- Children socialize parents just as parents socialize children.

- Such interchanges are sometimes referred to as transactional.

- It helps to think of the family as a constellation of subsystems defined in terms of generation, gender, and role.

- Dyadic subsystems — involving two people.

- Polyadic subsystems — involving more than two people.

- These subsystems interact and influence each other.

- A positive family climate involves not only effective parenting but also a positive relationship between the parents

Figure 1 Interaction Between Children and Their Parents: Direct and Indirect Effects

- What happens at home can reflect in the child's behaviour

Cognition and Emotion in Family Processes

- Cognition in family socialization includes:

- Parents’ thoughts, beliefs, and values about their role; and

- How parents perceive, organize, and understand their children’s behaviors and beliefs.

- Children’s social competence is also linked to the emotional lives of their parents.

- Through interaction with parents, children learn to express their emotions in appropriate ways.

- Parental sensitivity to children’s emotions is related to children’s ability to manage emotions in positive ways.

Multiple Developmental Trajectories

- Multiple developmental trajectories: the idea that adults follow one trajectory, and children and adolescents follow another.

- Adult developmental trajectories include timing of entry into marriage, cohabitation, and/or parenthood.

- Child developmental trajectories include timing of childcare and entry into middle school.

- The timing of some tasks and changes are planned, whereas others are not.

- Advantages of having children early (in the twenties):

- The parents are likely to have more physical energy.

- The mother is likely to have fewer medical problems.

- The parents may be less likely to build up expectations for their children.

- • Advantages to having children later (in the thirties):

- The parents will have more time to consider their life goals.

- They will be more mature and able to benefit from experience.

- They will be better established in their careers and have more income.

Sociocultural and Historical Changes

- Important sociocultural and historical influences affect family processes.

- This reflects the concepts of macrosystem and chronosystem.

- Example???

- Subtle and gradual changes are also significant.

- Longevity of older adults; movement to urban and suburban areas; widespread use of TV, computers, and the Internet; and an increase in family structural changes.

Parenting

- • Most parents learn parenting practices from their own parents.

- Both desirable and undesirable practices are perpetuated.

- Developmentalists consider such questions as:

- How should parents adapt their practice to developmental changes in their children?

- How important is it for parents to be effective managers of their children’s lives?

- How do various parenting styles and methods of discipline influence children’s development?

The Transition to Parenting

- In the transition to parenting, people must adapt to life with children.

- What can change? --- EVERYTHING

- The Bringing Baby Home project helps new parents.

- The workshop helps them strengthen their relationship, resolve conflict, and develop parenting skills.

- Parents are better able to work together, and babies show better overall development.

Infancy and Early Childhood (The Transition to Parenting)

- During the first year, parent – child interaction moves from a heavy focus on routine caregiving to gradually include non-caregiving activities, such as play.

- In early childhood, interactions focus on matters such as modesty and compliance, bedtimes, temper, fighting, eating, dressing, and attention seeking.

- Many new issues appear by the age of 7, such as chores, learning to entertain themselves, and how to monitor their lives outside the family.

Middle and Late Childhood (The Transition to Parenting:)

- In the middle and late childhood years, parents spend less time with children; but they continue to be extremely important in their children’s lives.

- They serve as gatekeepers and provide scaffolding.

- They support and stimulate children’s academic achievement.

- Children receive less physical discipline than they did as preschoolers.

- Gradually, some control is transferred from parent to child, producing coregulation.

Parents as Managers of Children’s Lives

- Parents can play important roles as managers of children’s opportunities, monitors of their lives, and social initiators and arrangers.

- They help children work their way through choices and decisions.

- In infancy, parents manage and guide behavior to reduce or eliminate undesirable behaviors.

- Parents’ management of toddler behavior includes corrective feedback and discipline.

- Parents can serve as regulators of opportunities for their children’s activities.

- Mothers are more likely than fathers to have a managerial role in guiding and managing children’s activities.

- Family - management practices are related to students’ grades and self - responsibility.

- Effective monitoring becomes especially important as children move into the adolescent years.

- Parents supervise the choice of social settings, activities, friends, and academic efforts.

- Adolescents manage parents’ access to information, disclosing or concealing details of their activities.

- Adolescents are more likely to disclose information when parents engage in positive parenting practices.

Figure 2 Parents’ Methods for Managing and Correcting Infants’ Undesirable Behavior

Method | 12 Months | 24 Months |

Spank with hand | 14% | 45% |

Slap infant’s hand | 21% | 31% |

Yell in anger | 36% | 81% |

Threaten | 19% | 63% |

Withdraw privileges | 18% | 52% |

Time - out | 12% | 60% |

Reason | 85% | 100% |

Divert attention | 100% | 100% |

Negotiate | 50% | 90% |

Ignore | 64% | 90% |

• Shown here are the percentages of parents who had used various corrective methods by the time the infants were 12 and 24 months old.

Parenting Styles and Discipline

- Good parenting takes time and effort.

- The quantity of time and quality of parenting both matter.

- Baumrind’s parenting styles:

- Authoritarian parenting: a restrictive, punitive style.

- Authoritative parenting: places limits while encouraging independence.

- Neglectful parenting: very uninvolved.

- Indulgent parenting: very involved but with few demands.

- Parenting styles involve dimensions of acceptance and responsiveness and demand and control.

Figure 3 Classification of Parenting Styles

• The four types of parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful) involve the dimensions of acceptance and responsiveness, on the one hand, and demand and control on the other. For example, authoritative parenting involves being both accepting/responsive and demanding/controlling.

Parenting Styles and Discipline slide 2

- Authoritative parenting is linked with child competence across a range of ethnic groups, social strata, cultures, and family structures.

- Parenting styles do not capture the important themes of reciprocal socialization and synchrony.

- Many parents use a combination of techniques.

- Two parents may have different styles.

- Most individuals who are favorable toward corporal punishment are likely to remember it being used by their parents.

- Corporal punishment is associated with higher levels of aggression later in childhood and adolescence.

- Cultural contexts are significant.

- In countries where physical punishment is considered normal, the effects of physical punishment are less harmful to children’s development. Why do you think that is?

- How do you handle misbehavior? Is it acceptable?

Figure 4 Corporal Punishment in Different Countries

- A 5 - point scale was used to assess attitudes toward corporal punishment, with scores closer to 1 indicating an attitude against its use and scores closer to 5 suggesting an attitude favoring its use.

Parenting Styles and Discipline Slide 3

Coparenting: the support that parents provide one another in jointly raising a child.

- Children are placed at risk for problems by:

- Poor coordination between parents;

- Undermining of the other parent;

- Lack of cooperation and warmth; and

- Disconnection by one parent.

Child Maltreatment

- Child abuse refers to both abuse and neglect.

- Child maltreatment is the term more often used by developmentalists.

- The term better acknowledges that maltreatment includes diverse conditions.

- Types of maltreatment:

- Physical abuse

- Child neglect

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Forms of child maltreatment often occur in combination.

- Factors, including culture, neighborhood, family, and development, likely contribute to child maltreatment.

- Among the consequences of child maltreatment:

- Poor emotion regulation;

- Attachment problems;

- Problems in peer relations;

- Difficulty adapting to school; and

- Other psychological problems, such as depression and delinquency

Figure 6 Old and New Models of Parent - Adolescent Relationships

Parent – Adolescent Relationships

- Parent - child attachment remains important.

- Although adolescents are moving toward independence, they still need to stay connected with families.

- Parent - adolescent conflict increases during early adolescence.

- What types of conflict can arise?

- A high degree of conflict does characterize some parent - adolescent relationships.

- Acculturation - based conflicts are likely in immigrant families.

Sibling Relationships

- Approximately 77% of American children have one or more siblings.

- Conflict between siblings is common.

- Higher sibling conflict has been linked to increased depressive and delinquency symptoms.

- Higher sibling intimacy is related to prosocial behavior.

- Sibling relationships in adolescence are not as close, not as intense.

- Characteristics of sibling relationships:

- Emotional quality of the relationship;

- Familiarity and intimacy of the relationship; and

- Variation in sibling relationships.

Birth Order

- Birth order has been linked to personality characteristics.

- First - born children are described as more adult oriented, helpful, conforming, and self - controlled.

- Variations in interactions with parents and sibling associated with being in a specific position in the family may produce birth - order effects.

Working Parents

- Maternal employment is part of modern American life.

- However, the effects of parental work involve both parents when work schedules and work - family stress are considered.

- Work has positive and negative effects on parenting:

- Positive

- Negative

Children in Different Family Dynamics

• Divorced

• Stepfamilies/Blended Families

• Gay/Lesbian Parents

• What factors are involved in determining how family dynamics influences a child’s development?

Children in Divorced Families

- Problems may stem as much from marital conflict as from divorce.

- Emotional security theory suggests that children appraise marital conflict in terms of their sense of security and safety.

- Adolescent adjustment is improved when divorced parents have a harmonious relationship and use authoritative parenting.

- Joint - custody arrangements work best for children when the parents get along with each other.

- Custodial mothers experience a much more substantial loss of their predivorce income, but the difference is getting smaller.

Stepfamilies

- Remarried parents must simultaneously:

- Define and strengthen their marriage;

- Renegotiate the biological parent - child relationships; and

- Establish stepparent - stepchild and stepsibling relationships.

- • Common types of stepfamily structure:

- Stepfather;

- Stepmother; and

- Blended or complex.

- Children often have better relationships with custodial parents than with stepparents.

- Children in simple stepfamilies show better adjustment than counterparts in complex (blended) stepfamilies.

- As in divorced families, children in stepfamilies show more adjustment problems than children in nondivorced families.

- However, the majority do not have problems.

Gay and Lesbian Parents

- Increasingly, gay and lesbian couples are creating families that include children.

- Just over one - third of all lesbian and gay couples are parents.

- Few differences have been found between children growing up with gay fathers or lesbian mothers and children growing up with heterosexual parents.

- The majority of the children have a heterosexual orientation.

Cultural, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Variations in Families

- • Different cultures often have different answers to basic questions about family, such as:

- • What should the father’s role be?

- What support systems are available?

- How should children be disciplined?

- • The most common parenting pattern is a warm and controlling style, one that is neither permissive nor restrictive.

Cultural, Ethnic,

and

Socioeconomic

Variations in

Families

Families within different ethnic groups in the

United States differ in typical size, structure,

composition, reliance on kinship, and income

and education.

• Large and extended families are more common among

minority groups.

• Single - parent families are more common among African

Americans and Latinos.

Some aspects of home life can help protect

ethnic minority children from injustice and

discrimination.

• The family can filter out racist messages and present

alternative frames of reference.

Cultural, Ethnic,

and

Socioeconomic

Variations in

Families

Lower - SES parents:

Are more concerned that their

children conform to society’s

expectations;

Create a home in which it is clear

parents have authority over children;

Use physical punishment more; and

Are more directive and less

conversational with children.

Higher - SES parents:

Are more concerned with developing

children’s initiative;

Create a home in which children are

more equal participants;

Are less likely to use physical

punishment; and

Are less directive and more

conversational.

Parents in different socioeconomic groups also tend to think differently about

education.

• Middle - and upper - income parents more often see education as something

that should be mutually encouraged by parents and teachers.

• Low - income parents are more likely to view education as the teacher’s job.

• Increased school - family linkages especially can benefit students from low -

income families.

Finish adding notes

Finish adding notes

Peers W10 M3

Exploring Peer Relations

- Peers: children who share the same age or maturity level.

- They provide a source of information and comparison about the world outside the family.

- Children receive feedback about their abilities from peers.

- Good peer relations may be necessary for social development.

- Social isolation is linked with problems and disorders ranging from delinquency to problem drinking and Depression.

- Peer influences can be both positive and negative.

- The cognitive skills or deficits of peers may play a key role in skills development.

- Rejection and neglect by peers leads to loneliness and hostility and is linked to mental health and criminal issues.

- Peers can undermine parents’ values and control.

- Individual differences among peers also are important to consider.

- These include personality traits such as how shy or outgoing children are; and the impact of negative emotionality.

The Developmental Course of Peer Relations in Childhood

- Infants: attend childcare, peer interaction in infancy takes on a greater role.

- Toddler: around age 3, children prefer to spend time with same - sex playmates.

- This preference increases in early childhood.

- Preschool: years the frequency of positive and negative peer interactions increases.

- Early childhood: children distinguish between friends and non - friends.

- A friend is someone to play with.

- Elementary school years: reciprocity becomes important in peer interchanges.

- The amount of time spent in peer interaction also rises in middle and late childhood and adolescence.

- The size of peer groups increases, they are less closely supervised by adults, and social media begin to play a role.

- Peer interactions take varied forms:

- Cooperative and competitive;

- Boisterous and quiet;

- Joyous and humiliating.

- Gender influences the composition of children’s groups, their size, and the types of interactions.

- Boys tend to associate in large clusters, whereas girls are more likely to play in groups of two or three.

- Boys’ groups engage in competition and dominance seeking; girls’ groups are more likely to engage in collaborative activity.

The Distinct But Coordinated Worlds of Parent - Child and Peer Relations

- Parents may influence their children’s peer relations in many ways, both direct and indirect.

- Basic lifestyle decisions largely determine the pool from which children select possible friends.

- Children also learn other modes of interacting through their relationships with peers.

-- Connected to attachment style that YOU HAVE DEVELPEMED and is it positive

Why might you have agroup of friend

- One might be bully

- One might be loose gooses

- One is here and there

- One is secure

ON EXAM

- Friends could be infince they hvaing not so strong attachments they want to hang out with people

- You could have multplie attachment styles, good mom, insuce dad, odd conect with educator

- You find they simplar in a way and need the confort of fermilatity

Realtes to parents

Who did they sociaze with

Did they go out oftwen

Did they host parties, what does it look like

Do you go over to people house wjat did it look like

- You will follow with the farmialtly of what you grew up with

Social Cognition and Emotion

- Social cognition — thoughts about social situations — becomes increasingly important for understanding peer relationships in middle and late childhood.

- Possible influences on peer relations include:

- Children’s perspective - taking ability;

- Social information - processing skills;

- Social knowledge; and

- Emotional regulation.

- Perspective taking involves perceiving another’s point of view.

- It is important in part because it helps children communicate.

- Kenneth Dodge (1993) argues children go through five steps in processing social information:

1. Decoding social cues;

2. Interpreting;

3. Searching for a response;

4. Selecting an optimal response; and

5. Enacting it.

- As children and adolescents develop, they acquire more social knowledge — what it takes to make friends, to get peers to like them, and so forth.

- Emotions play a strong role in determining whether peer relations are successful.

- The ability to regulate emotion is linked to successful peer relations.

- Moody and emotionally reactive children face more rejection.

- Emotionally positive children are more popular.

Peer Statuses

- Developmentalists distinguish five peer statuses:

- Popular children are frequently nominated as best friend and rarely disliked by peers.

- Average children receive an average number of both positive and negative nominations from peers.

- Neglected children are infrequently nominated as best friend but not disliked by peers.

- Rejected children are infrequently nominated as a best friend and are actively disliked by peers.

- Controversial children are frequently nominated both as a best friend and as being disliked.

• Popular children have social skills that contribute to being well liked:

- They give out reinforcements;

- Listen carefully;

- Maintain open lines of communication;

- Are happy;

- Control negative emotions;

- Show enthusiasm and concern for others; and

- Are self - confident without being conceited.

Neglected children engage in low rates of interaction with peers and are often described as shy.

Rejected children often have more serious adjustment problems than those who are neglected.

Rejection and victimization from peers appears to be a strong, consistent predictor of decreases in school engagement and academic achievement.

Peer Rejection and Aggression

- The combination of being rejected by peers and being aggressive especially forecasts problems.

- Poor parenting skills in early childhood and the elementary school years are among the root problems.

- By adolescence, it is difficult to improve skills of youth who are actively disliked and rejected.

- Peer group reputations become more fixed as cliques and peer groups become more salient.

Bullying

- Bullies report their parents tend to be authoritarian, physically punish them, lack warmth, and show indifference to their children.

- Bullied children report more loneliness and more difficulty making friends.

- They are often anxious, socially withdrawn, and aggressive.

- Social contexts influence bullying.

- Most victims and bullies are in the same classroom.

- Classmates are often aware of and witness bullying.

- Bullies torment victims to gain a higher status and are rarely rejected by their peer group.

- Bullied children are more likely to experience depression, engage in suicidal ideation, and attempt suicide.

- Intervention by school personnel is the most common way that bullying is stopped.

- These strategies are recommended:

- Get older peers to serve as monitors for bullying.

- Develop school - wide rules and sanctions against bullying.

- Form friendship groups for those who are bullied.

- Incorporate an antibullying message into other community activity areas such as places of worship.

- Encourage parents to reinforce and model positive interpersonal interactions.

- Identify bullies and victims early.

- Encourage parents to contact the school’s psychologist, counselor, or social worker for help.

Friendship

- • Functions of friendship:

- Companionship;

- Stimulation;

- Physical support;

- Ego support;

- Social comparison; and

- Affection and intimacy.

- The quality of friendship is also important to consider.

Friendship: Similarity and Intimacy

- Children’s friendships are characterized by similarity.

- Age, sex, ethnicity, and many other factors.

- Often similar attitudes toward school, similar educational aspirations, and closely aligned achievement orientations.

- Priorities change as the child reaches adolescence.

- Intimacy in friendship: self - disclosure or the sharing of private thoughts.

Gender and Friendship

- Research indicates girls’ friendships are more intimate.

- Girls mention intimate conversations and faithfulness.

- One problematic aspect is that girls’ co – rumination (excessively discussing problems) can bring an increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms.

- Boys give more importance to having a congenial friend with whom they can share interests and activities.

- They tend to emphasize power and excitement.

- It is important for both girls and boys that they have close friendships and peers that support them.

Mixed – Age Friendships

- Some adolescents become friends with younger or older individuals.

- Those who interact with older youth do engage in problematic behaviors more frequently.

- Over time, girls are more likely to have older male friends, which for some makes problem behavior more likely.

- Mixed - age friends may be protective, however, for friendless adolescents.

Other – Sex Friendships

- The number of other - sex friendships increases in the transition to and across adolescence.

- Girls report more other - sex friends than boys.

- Mixed - sex groups provide a context for adolescents to learn how to communicate with the other sex and reduce anxiety in social and dating heterosexual interactions.

- Other - sex friendships are sometimes linked to negative behaviors such as earlier sexual intercourse, alcohol use, and delinquency.

- Parents likely monitor daughters’ other - sex friendships more closely than their sons’.

Romantic Relationships

• Adolescents spend considerable time engaged in romantic relationships or thinking about doing so.

• Three stages characterize the development of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence:

• Entry into romantic attractions and affiliations at about 11 to 13 years of age;

• Exploring romantic relationships at approximately 14 to 16 years of age — including casual dating and dating in groups.

• Consolidating dyadic romantic bonds at about 17 to 19 years of age.

• Early bloomers include 15 to 20% of 11 - to 13 - year – olds who say they are currently in a romantic relationship and 35% who indicate they have had some prior experience.

• Late bloomers comprise approximately 10% of 17 – to 19 - year - olds who say they have no experience with romantic relationships and another 15% who have not engaged in one that lasted more than 4 months.

• Early romantic relationships serve as a context for exploring how attractive they are, how to interact romantically, and how these aspects look to peers.

Language and Intelligence Week 11 M3

What Is Language?

- Language is a form of communication — whether spoken, written, or signed — based on a system of symbols.

- It consists of the words used by a community and the rules for varying and combining them.

- All human languages have some common characteristics:

- Infinite generativity: the ability to produce an endless number of meaningful sentences using a finite set of words and rules.

- Language is orderly, and rules describe the way the language works.

When English is not the first language, they will learn it fast an English is a language that is easy to learn from a different language.

Figure 5.12 - the rule systems of Language

How Language Develops

- Infants use early vocalizations to practice making sounds, to communicate, and to attract attention.

- Crying, with different types signaling different things;

- Cooing, first emerging at 1 to 2 months; and

- Babbling, often around the middle of the first year.

- Gradually they lose the ability to recognize differences not found in their own language

- Toddlers move rather quickly from two - word utterances to creating three - , four - , and five - word combinations.

- During the preschool years, most children become more sensitive to the sounds of spoken words and more able to produce all the sounds of their language.

Language development needs support

Environmental Factors influence language:

- How can these findings be applied to early childhood settings? What are some strategies or practices you could use?

- Can factors such as group size, ratios and the organization of physical space affect the amount of adult/child communication that occurs?

- How can you use this information when working with parents?

How Language Develops: Early Childhood

Six key principles in vocabulary development:

- Children learn the words they hear most often.

- Children learn words for things and events that interest them.

- Children learn words best in responsive and interactive contexts rather than in passive contexts.

- Children learn words best in contexts that are meaningful.

- Children learn words best when they access clear information about word meaning.

- Children learn words best when grammar and vocabulary are considered.

The Concept of Intelligence

Intelligence: the ability to solve problems and to adapt and learn from experiences.

- Other definitions often have different emphases, including:

- Creativity and interpersonal skills; and

- The ability to use the tools of the culture with help from more - skilled individuals.

- Individual differences in intelligence are measured by intelligence tests designed to tell whether a person can reason better than others who have taken the test.

Intelligence Tests: The Binet Tests

- Alfred Binet was asked to devise a method of identifying children who were unable to learn in school.

- He developed the concept of mental age (MA) , an individual’s level of mental development relative to others.

- William Stern then created the concept of intelligence quotient (IQ) , a person’s mental age divided by chronological age (CA), multiplied by 100.

- If mental age is the same as chronological age, the IQ is 100.

Intelligence Tests: The Binet Tests 2

- The current, fifth edition of the Stanford - Binet test analyzes an individual’s responses in five content areas.

- It includes both verbal and nonverbal subscales that assess knowledge, quantitative reasoning, visual - spatial processing, working memory, and fluid reasoning.

- It is scored by comparing one’s performance with the results of others of the same age.

- Normal distribution: a symmetrical, bell - shaped curve with a majority of cases falling in the middle of the possible range.

- Stanford - Binet continues to be one of the most widely used individual tests of intelligence.

Figure 1 The Normal Curve and Stanford - Binet IQ Scores

• The distribution of IQ scores approximates a normal curve. Most of the population falls in the middle range of scores. Notice that extremely high and extremely low scores are very rare. Slightly more than two - thirds of the scores fall between 84 and 116. Only about 1 in 50 individuals has an IQ above 132, and only about 1 in 50 individuals has an IQ below 68.

Intelligence Tests: The Wechsler Scales

- • Another set of tests is the Wechsler scales, developed by David Wechsler.

- The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Fourth Edition (WPPSI - IV) tests children from 2 years 6 months to 7 years 3 months of age.

- The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fifth Edition (WISC - V) is for children and adolescents 6 to 16 years of age.

- The Wechsler scales provide an overall IQ score but also yield several composite indexes.

The Use and Misuse of Intelligence Tests

- Intelligence tests may predict longevity and school and work success, but many other factors contribute.

- The single number can easily lead to false expectations.

- Sweeping generalizations are too often made on the basis of an IQ score and can become self – fulfilling prophecies.

- Intelligence tests should be used in conjunction with other information.

- This would include developmental history, medical background, school performance, social competencies, family experiences, etc.

Theories of Multiple Intelligences

- According to Robert J. Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence, intelligence comes in three forms:

- Analytical intelligence: ability to analyze, judge, evaluate, compare, and contrast.

- Creative intelligence: ability to create, design, invent, originate, and imagine.

- Practical intelligence: ability to use, apply, implement, and put ideas into practice.

- Children with high analytic ability tend to be favored in conventional schooling.

- Sternberg argues that wisdom is linked to both practical and academic intelligence.

- Academic intelligence is a necessary but in many cases insufficient requirement for wisdom.

- Practical knowledge about the realities of life is also needed.

Theories of Multiple Intelligences

- Howard Gardner says there are many types of intelligence, or frames of mind:

- Verbal skills, such as among journalists;

- Mathematical skills, such as among engineers;

- Spatial skills, such as about architects;

- Bodily - kinesthetic skills, such as among surgeons or dancers;

- Musical skills, such as among musicians and composers;

- Intrapersonal skills, such as among psychologists;

- Interpersonal skills, such as among teachers; and

- Naturalist skills, such as among farmers and ecologists.

Theories of Multiple Intelligences: Entity versus Incremental

- Individuals who hold entity theories believe that intelligence is primarily something people are born with that does not change much over time.

- Individuals who hold incremental theories believe that intelligence can grow over time and be improved through hard work.

- Students who hold incremental theories of intelligence are more motivated to work hard.

- Parents and teachers who hold incremental theories are more likely to praise effort rather than ability.

Theories of Multiple Intelligences: Emotional Intelligence

- Sternberg’s and Gardner’s theories both include one or more categories related to understanding oneself and others and getting along in the world.

- Emotional intelligence emphasizes these interpersonal, intrapersonal, and practical aspects — conceptualized by Peter Salovey and John Mayer as the ability to:

- Perceive and express emotion accurately and adaptively;

- Understand emotion and emotional knowledge;

- Use feelings to facilitate thought; and

- Manage emotions in oneself and others.

How is EI developed?

Theories of Multiple Intelligences: Emotional Intelligence

- Interventions to improve emotional intelligence that focus on how to regulate emotion have been found to:

- Reduce anger and other negative emotions; and

- Reduce physical and verbal aggression.

- For adolescents who have been cyberbullied, higher emotional intelligence plays a protective role.

- Critics argue that emotional intelligence broadens the concept of intelligence too far to be useful and has not been adequately assessed and researched.

- They also argue it is not a form of intelligence per se.

The Neuroscience of Intelligence

- Researchers now agree that intelligence is distributed widely across brain regions and depends on connectivity and coordination among different areas.

- Recent work suggests that as much as 80% of the variance in general intelligence can be explained by the speed with which individuals process information.

- As the technology to study the brain’s functioning continues to advance, new conclusions will be reached.

Figure 3 Intelligence and the Brain

Researchers have found that a higher level of intelligence is linked to a distributed neural network in the frontal and parietal lobes. To a lesser extent than the frontal/parietal network, the temporal and occipital lobes, as well as the cerebellum, also have been found to have links to intelligence. The current consensus is that intelligence is likely to be distributed across brain regions rather than being localized in a specific region such as the frontal lobes.

The Influence of Heredity and Environment

- Researchers agree that both heredity and environment influence intelligence.

- Using genome - wide association studies, researchers have found that thousands of genetic sequences contribute to intelligence.

- Both twin studies and adoption studies have been used to analyze the relative importance of heredity.

Figure 4 Correlation Between Intelligence Test Scores and Twin Status

• The graph represents a summary of research findings that have compared the intelligence test scores of identical and fraternal twins. An approximate 0.15 difference has been found, with a higher correlation for identical twins (0.75) and a lower correlation for fraternal twins (0.60).

The Influence of Heredity and Environment

- Heritability: the fraction of the variance in a population that is attributed to genetics.

- A key point to keep in mind about heritability is that it refers to a specific group (population), not to individuals.

- It says nothing about why a single individual has a certain intelligence, nor does it say anything about differences between groups.

- Genes and the environment always work together.

- The Flynn effect refers to a worldwide increase in scores over a relatively short amount of time.

- The increase may be due to vastly greater access to information and to generally increasing levels of education.

- Factors such as prenatal and postnatal nutrition may also be related.

Figure 5 The Increase in IQ Scores from 1932 to 1997

- As measured by the Stanford - Binet intelligence test, American children seem to be getting smarter. Scores of a group tested in 1932 fell along a bell - shaped curve with half below 100 and half above. Studies show that if children took that same test today, half would score above 120 on the 1932 scale. Very few of them would score in the “intellectually deficient” range on the left side, and about one - fourth would rank in the “very superior” range.

Group Comparisons

- Cross - cultural comparisons show that cultures vary in what it means to be intelligent.

- Western cultures emphasize reasoning and thinking skills.

- Individuals can demonstrate intellectual skills in different ways.

- Cultural bias is an issue in testing.

- Early intelligence tests favored people from urban environments, middle socioeconomic status, and White rather than African American ethnicity.

- Those that do not speak standard English are at a disadvantage in understanding questions in standard English.

- Sometimes intelligence tests are used to compare one demographic group with another.

- Average scores are being compared.

- Group averages sometimes favor one group.

- For example, when males outperform females on math tests, or when European Americans outperform African Americans.

- One potential influence on test performance is stereotype threat — the anxiety that one’s behavior might confirm a negative stereotype about one’s group.

The Development of Intelligence: Tests of Infant Intelligence

- Tests of infant intelligence are less verbal and contain elements related to perceptual - motor development and social interaction.

- Arnold Gesell (1934) developed a measure that helped sort out typically developing from atypically developing babies.

- The current version of the Gesell test has four categories of behavior: motor, language, adaptive, and personal - social.

- The developmental quotient (DQ) combines subscores in these categories to provide an overall score.

- The widely used Bayley - III Scales of Infant Development were developed by Nancy Bayley (1969) to assess behavior and predict later development.

- The current version (Bayley - III) has five scales: cognitive, language, motor, socio - emotional, and adaptive.

- Several studies have found that measures of intelligence in infancy are correlated with measures of intelligence later in childhood.

- Some important changes in cognitive development occur after infancy, however

Stability and Change in Intelligence Through Adolescence

- Intelligence test scores can fluctuate dramatically across the childhood years.

- Children are adaptive — their intelligence changes but remains connected with earlier points in development.

Intellectual Disability 1

- Intellectual disability and intellectual giftedness are the extremes of intelligence.

- Intellectual disability is a condition of limited mental ability in which the individual:

- Has a low IQ, usually below 70 on a traditional test;

- Has difficulty adapting to everyday life; and

- First exhibits these characteristics by age 18.

- Organic intellectual disability : a genetic disorder or lower level of intelligence due to brain damage.

- Down syndrome, abnormality of the X chromosome, prenatal malformation, metabolic disorders, and brain diseases.

- Most have IQs between 0 and 50.

- Cultural - familial intellectual disability : cases with no evidence of organic brain damage.

- Often emerge from below - average intellectual environments.

- Most have IQs between 55 and 70.

- Disability is usually not noticeable in adulthood.

Figure 6 Classification of Intellectual Disability Based on IQ

Type of Intellectual Disability IQ Range Percentage

Mild 55 to 70 89%

Moderate 40 to 54 6%

Severe 25 to 39 4%

Profound Below 25 1%

Giftedness

- Those who are gifted have high intelligence and/or superior talent of some kind.

- An IQ of 130 is often used as the low threshold.

- Approximately 3 to 5% of U.S. students are gifted.

- Estimates focus more on children who are gifted intellectually and academically.

- They often fail to include those who are gifted in creative thinking or the visual and performing arts.

- In general, no connection between giftedness and mental disorder has been found.

Giftedness

- Three criteria characterize gifted children:

- Precocity;

- Marching to their own drummer; and

- A passion to master.

- Giftedness is a product of both heredity and environment.

- Individuals who are gifted often demonstrate special abilities from an early age, before formal training.

- Individuals with world - class status in their gifted domain all report strong family support and years of training and practice.

- Highly gifted individuals are not typically gifted in many domains.

- Domains of giftedness usually emerge in childhood.

- Many gifted children do not become gifted and highly creative adults.

- Gifted children who are insufficiently challenged can become disruptive, skip classes, and lose interest.

- Too often, they are socially isolated and underchallenged.

Creativity

- Creativity is the ability to think about something in novel and unusual ways and to come up with unique solutions to problems.

- Intelligence and creativity are not the same thing.

- Creativity requires divergent thinking, which produces many answers to the same question.

- Conventional intelligence tests measure convergent thinking, in which there is only one correct answer.

- Creative thinking appears to be declining.

- Among the likely causes in the United States are the number of hours spent watching TV, engaging with social media, and playing video games; and a lack of emphasis on creative thinking in schools.

M4 Mental Health in Childhood week 13

AS EARLY EXPERIENCES SHAPE THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE

DEVELOPING BRAIN , THEY ALSO LAY THE FOUNDATIONS OF

SOUND MENTAL HEALTH. DISRUPTIONS TO THIS

DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS CAN IMPAIR A CHILD’S

CAPACITIES FOR LEARNING AND RELATING TO OTHERS —

WITH LIFELONG IMPLICATIONS. BY IMPROVING CHILDREN’S

ENVIRONMENTS OF RELATIONSHIPS AND EXPERIENCES

EARLY IN LIFE, SOCIETY CAN ADDRESS MANY COSTLY

PROBLEMS, INCLUDING INCARCERATION, HOMELESSNESS,

AND THE FAILURE TO COMPLETE HIGH SCHOOL.”

- HARVARD CENTER FOR THE DEVELOPING CHILD

How you are treated as a child has an effect as well as your attachment

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES

Or ACE’s

WHAT ARE ACES?

REVIEW THE DOCUMENT

WHAT ARE ACES?

WHAT ARE INDICATORS?

WHAT IS YOUR ROLE AS AN ECE ?

SIGNIFICANT MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS CAN OCCUR IN YOUNG CHILDREN

- Children can show clear characteristics of anxiety disorders, attention - deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as autism, at a very early age.

- Diagnosis in early childhood can be much more difficult than it is in adults.

THE INTERACTION OF GENES AND EXPERIENCE AFFECTS CHILDHOOD MENTAL HEALTH.

Our genes contain instructions that tell our bodies how to work, but the chemical “signature” of our environment can authorize or prevent those instructions from being carried out. The interaction between genetic predispositions and sustained, stress - inducing experiences early in life can lay an unstable foundation for mental health

TOXIC STRESS CAN DAMAGE BRAIN ARCHITECTURE AND INCREASE THE LIKELIHOOD THAT SIGNIFICANT MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS WILL EMERGE EITHER QUICKLY OR YEARS LATER.

- toxic stress can impair school readiness, academic achievement, and both physical and mental health throughout the lifespan.

- Circumstances associated with family stress, such as persistent poverty, may elevate the risk of serious mental health problems.

- Young children who experience recurrent abuse or chronic neglect, domestic violence, or parental mental health or substance abuse problems are vulnerable.

ACE’S AND HEALTH ISSUES

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE, BUT EARLIER IS BETTER.

- SOME INDIVIDUALS DEMONSTRATE REMARKABLE CAPACITIES TO OVERCOME THE SEVERE CHALLENGES OF EARLY, PERSISTENT MALTREATMENT, TRAUMA, AND EMOTIONAL HARM, YET THERE ARE LIMITS TO THE ABILITY OF YOUNG CHILDREN TO RECOVER PSYCHOLOGICALLY FROM ADVERSITY.

“MOST POTENTIAL MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS WILL NOT BECOME MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IF WE RESPOND TO THEM EARLY.”

HARVARD CENTER FOR THE DEVELOPING CHILD

IT IS ESSENTIAL TO TREAT YOUNG CHILDREN’S MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS WITHIN THE CONTEXT OF THEIR FAMILIES, HOMES, AND COMMUNITIES.

- The emotional well - being of young children is directly tied to the functioning of their caregivers and the families in which they live. When these relationships are abusive, threatening, chronically neglectful, or otherwise psychologically harmful, they are a potent risk factor for the development of early mental health problems.

- When relationships are supportive, they can actually buffer young children from the adverse effects of other stressors. Therefore, reducing the stressors affecting children requires addressing the stresses on their families.

BUILDING RESILIENCE ARMSTRONG, L . (2018), STRENGTHENING CHILDREN’S RESILIENCE AND MENTAL HEALTH , THINK FEEL ACT: QUEENS PRINTER FOR ONTARIO

BUILDING RESILIENCE (ARMSTRONG, 2018)

• “CHILDREN WHO ARE RESILIENT HAVE THE EMOTIONAL, SOCIAL, AND BEHAVIOURAL SKILLS TO SUCCESSFULLY NAVIGATE LIFE’S CHALLENGES. RESILIENT CHILDREN FACE HARDSHIPS COURAGEOUSLY AND MAY EVEN THRIVE WHEN CONFRONTED WITH DIFFICULTIES”.

• ARMSTRONG, L. (2018)

MENTAL HEALTH CAN BE UNDERSTOOD AS A CONTINUUM

• MENTAL HEALTH CAN BE UNDERSTOOD AS A CONTINUUM ALONG WHICH PEOPLE MAY MOVE, INFLUENCED BY MULTIPLE INTERRELATED FACTORS. PROVIDING CONSTRUCTIVE SUPPORTS FOR RESILIENCE HELPS CHILDREN LEARN SKILLS FOR COPING THAT CAN CONTRIBUTE TO LIFELONG MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL – BEING

IN ONTARIO, UP TO 21 PER CENT OF CHILDREN AND YOUTH – OR APPROXIMATELY 650,000 – EXPERIENCE MENTAL ILLNESS

- OFFICE OF THE PROVINCIAL ADVOCATE FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH FOR ONTARIO (2015) AS CITED IN ARMSTRONG, 2018.

BUILDING RESILIENCE THROUGH MINDSET

- • BUILD RESILIENCE IN CHILDREN BY HELPING THEM CULTIVATE A MEANING MINDSET.

- • FOR CHILDREN, MEANING CAN BE FOUND IN THE FOLLOWING THOUGHTS AND BEHAVIOURS

- • BELIEVING IN THEIR OWN ABILITY AND SKILLS TO CHALLENGE UNHELPF UL THOUGHTS, PROBLEM SOLVE, AND TAKE A HEALTHY, REALISTIC STANCE TOWARD CHALLENGES

- • IN THE FACE OF DIFFICULT FEELINGS, TAKING HELPFUL ACTION TO FE EL LESS SAD, ANGRY, OR SCARED

- • HELPING OTHERS, VOLUNTEERING, AND GIVING TO OR CREATING SOMETH ING FOR OTHERS

- • DEVELOPING AND MAINTAINING POSITIVE SOCIAL CONNECTIONS (E.G., SECURE, SUPPORTIVE RELATIONSHIPS WITH ADULTS AND PEERS),

- AND FEELING VALUED BY OTHERS

- • BEING REGULARLY INVOLVED IN VALUED ACTIVITIES (E.G., SPORTS, M USIC, OR OTHER EXTRACURRICULAR ACTIVITIES) THAT THEY LOOK FORWARD TO, WOULD HAVE DIFFICULTY GIVING UP, AND PERCEIVE AS “FU N”

- • HAVING CURIOSITY, AND OPENNESS TO LEARNING AND OTHER NEW EXPER IENCES

- • EXPERIENCING MEANINGFUL MOMENTS (E.G., EXPERIENCING NATURE, BE ING EXCITED BY LEARNING, NOTICING EVERYDAY JOYS)

- • EXPRESSING GRATITUDE OR APPRECIATION IN EVERYDAY EXPERIENCES

- • MAINTAINING HOPE, EVEN IN THE FACE OF DIFFICULTIES

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION’S HOW DOES LEARNING HAPPEN? ONTARIO’S PEDAGOGY FOR THE EARLY YEARS (2014).

• CULTIVATING HEALTHY MINDSET INVOLVES CREATING PROGRAMS THAT ARE BASED ON A VIEW OF CHILDREN AS COMPETENT, CAPABLE, CURIOUS, AND RICH IN POTENTIAL, AND FOCUSING ON THE FOLLOWING FOUR FOUNDATIONS FOR LEARNING:

- BELONGING: CONNECTING WITH OTHERS, FEELING VALUED BY OTHERS, FORMING RELATIONSHIPS, CONTRIBUTING TO THE COMMUNITY OR TO A GROUP, CONNECTING TO THE NATURAL WORLD

- WELL - BEING: MAINTAINING PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH THROUGH SELF - CARE, SENSE OF SELF, AND SELF - REGULATION SKILLS

- ENGAGEMENT: BEING INVOLVED AND FOCUSED, CURIOUS, AND OPEN, THEREBY DEVELOPING PROBLEM - SOLVING AND CREATIVE - THINKING SKILLS

- EXPRESSION OR COMMUNICATION: COMMUNICATING AND LISTENING TO OTHERS, DEVELOPING THE ABILITY TO CONVEY INFORMATION, IDEAS, AND FEELINGS THROUGH BODIES, WORDS, OR MATERIALS

RESILIENCE IN EVERYDAY LIFE

- Healthy Thinking (e.g. identify self defeating talk)

- Healthy Behavioural Tools (e.g. listening to music, playing outside)

- “Me to We” Environment (e.g. doing things for others)

- Affection before Correction (as noted in Self Regulation discussion, if alarmed, a child can not engage in adaptive behaviour – soothe limbi brain first)

- Culture of Engagement (e.g. involvement in activities)

- Openness (e.g. having a growth mindset)

- Gratitude (e.g. notice what we appreciate)

WHAT IS YOUR ACE SCORE?

• COMPLETE THE TEST USING THE LINK BELOW

• ACE TEST

• RESILIENCE TEST

• WHAT IS YOUR ACE SCORE?

• WHAT IS YOUR RESILIENCE SCORE?

• NOW WHAT?

POSITIVE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES (PCES)

• IMPORTANT NO MATTER HOW MUCH ACES HAVE BEEN EXPERIENCED

• THE MORE PCES THE LESS LIKELY CONSEQUENCES OF ACES ARE

CONSIDER:

- HOW MUCH OR HOW OFTEN DURING YOUR CHILDHOOD DID YOU:

- FEEL ABLE TO TALK TO YOUR FAMILY ABOUT FEELINGS;

- FEEL YOUR FAMILY STOOD BY YOU DURING DIFFICULT TIMES;

- ENJOY PARTICIPATING IN COMMUNITY TRADITIONS;

- FEEL A SENSE OF BELONGING IN HIGH SCHOOL;

- FEEL SUPPORTED BY FRIENDS;

- HAVE AT LEAST TWO NON - PARENT ADULTS WHO TOOK GENUINE INTEREST IN YOU; AND

- FEEL SAFE AND PROTECTED BY AN ADULT IN YOUR HOME.

WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS ABOUT PCES.

- • THE PRESENCE OF FLOURISHING INCREASED IN A GRADED FASHION WITH I NCREASING LEVELS OF FAMILY RESILIENCE AND CONNECTION

- • CHILDREN WITH HIGHER ACE SCORES WERE LESS LIKELY TO DEMONSTRATE RESILIENC E, LIVE IN A PROTECTIVE HOME ENVIRONMENT, HAVE A MOTHER WHO WAS HEALTHY, AND LIVE IN SAFE AND SUPPORTIVE NEIGHBORHOODS

- • GREATER CHILDHOOD FAMILY CONNECTION WAS ASSOCIATED WITH GREATER FLOURISHING IN US ADULTS ACROSS LEVELS OF CHILDHOOD ADVERSITY .

- • HE NUMBER OF ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES WAS ASSOCIATED WITH B OTH SOCIAL - EMOTIONAL DEFICITS AND DEVELOPMENTAL DELAY RISKS IN EARLY CHILDH OOD; HOWEVER, POSITIVE PARENTING PRACTICES DEMONSTRATED ROBUST PROTECTIVE EFFE CTS INDEPENDENT OF THE NUMBER OF ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES

- • POSITIVE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES] WERE ASSOCIATED WITH IMPROVED AD ULT HEALTH AND THAT COUNTER - ACES NEUTRALIZED THE NEGATIVE IMPACT OF ACES ON ADU LT HEALTH

Knowt

Knowt