GENETICS MIDTERM REVIEWER

4.1 Alleles Alter Phenotypes in Different Ways

Introduction to Genetic Inheritance

Mendel's work was rediscovered in the early 1900s, leading researchers to study how genes influence phenotypes in various ways.

This research prompted investigations into inheritance patterns that did not conform to expected Mendelian ratios.

Genetic Data and Phenotypes

Observations of genetic data led to new hypotheses, modifying and extending Mendelian principles.

The principle that governs these observations: a phenotype is controlled by one or more genes at specific loci on homologous chromosomes.

Understanding Alleles

Alleles: Alternative forms of the same gene.

Wild-type alleles: The allele that occurs most frequently in a population, often deemed normal. This allele is usually dominant and corresponds to the wild-type phenotype, used as a standard for comparison against mutations.

Mutant alleles: Possess modified genetic information and often specify an altered gene product. For example, in humans, multiple alleles encode the b chain of hemoglobin, each producing slightly different forms of the same molecule.

Function and Mutation of Alleles

The function of the product specified by an allele may vary based on the allele itself—resulting in potential changes in phenotype.

Source of Alleles: The process of mutation. For a new allele to be recognized, it must result in a change in phenotype.

A new phenotype arises from changes in the functional activity of the cellular product specified by that gene, often leading to a reduction or loss of the wild-type function.

Types of Mutations

Loss-of-function mutations: Result in reduced or eliminated function of the gene product. If the loss is complete, it is termed a null allele.

Gain-of-function mutations: Enhance the function of the wild-type product, typically through increases in the quantity of the gene product, often leading to dominant alleles. These mutations may convert proto-oncogenes to oncogenes, resulting in cancerous cells.

Neutral Mutations

Some mutations may not cause a detectable change in phenotype or functional impact, referred to as neutral mutations. They may only be identified at the DNA sequence level and do not affect the evolutionary fitness of the organism.

Polygenic Traits

While a phenotypic trait may be affected by a single mutation in one gene, many traits are influenced by multiple genes working together.

For example, enzymatic reactions are often parts of complex pathways leading to the synthesis of end products such as amino acids, with mutations in any gene affecting the overall synthesis process.

4.2 Geneticists Use a Variety of Symbols for Alleles

Symbolization of Alleles:

In Mendelian genetics, the convention to symbolize alleles involves using the initial letter of the name of a recessive trait.

Recessive Allele: Denoted with a lowercase, italicized letter (e.g.,

dfor dwarf).Dominant Allele: Denoted with an uppercase letter (e.g.,

Dfor tall).

Example: For tall and dwarf plants, the alleles are represented as

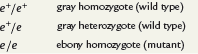

D(tall) andd(dwarf).Drosophila melanogaster System:

A specific system was developed for symbolizing traits in fruit flies to differentiate between wild-type and mutant traits.

Initial letter(s) of the name of the mutant trait is used:

Recessive trait: Lowercase (e.g.,

efor ebony body color).Wild-type trait: Denoted by the same letter with a superscript

+(e.g.,e+for gray).

Genotype Representation:

A diploid fly may exhibit three possible genotypes:

e/e+,e/e, ande+/e+.The

/indicates the alleles represent the same locus on two homologous chromosomes.Example of a dominant wing mutation (Wrinkled -

Wr): The genotypes could beWr+/Wr+,Wr+/Wr, andWr/Wr.

Abbreviation:

The wild-type allele can be abbreviated as

+to streamline notation (e.g.,efor ebony ande+for gray).

Non-Dominant Alleles:

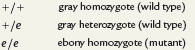

When no dominance exists, alternative alleles are represented with uppercase italic letters and superscripts (e.g.,

R1,R2,LM,LN,IA,IB).

Gene Symbolism Across Organisms:

Diverse genetic nomenclature systems exist:

Each symbol often reflects the gene's function or associated disorders.

Examples:

Yeast:

cdkfor cyclin-dependent kinase involved in cell cycle regulation.Bacteria:

leu-indicates a mutation affecting leucine biosynthesis (leu+for the wild-type allele).Humans: Genes are denoted with capital letters, such as

BRCA1associated with breast cancer susceptibility.

4.3 Neither Allele Is Dominant in Incomplete, or Partial, Dominance

Introduction to Incomplete Dominance

A cross between parents with contrasting traits may produce offspring with an intermediate phenotype.

Example: In plants like four-o’clocks or snapdragons, crossing red-flowered plants with white-flowered plants results in pink-flowered offspring.

This indicates that neither red nor white flower color is dominant and represents a case of incomplete dominance.

Genetic Control of Phenotype

If a phenotype is controlled by a single gene with two alleles, and neither allele is dominant, the F1 (pink) x F1 (pink) cross can be analyzed.

The resulting F2 generation exhibits a genotypic ratio of 1:2:1, which matches the ratio seen in Mendel’s monohybrid cross.

In this situation, the phenotypic ratio also mirrors the genotypic ratio (1:2:1).

Allele Designation

Because neither allele is dominant or recessive, traditional upper and lowercase letter symbols are avoided. Instead, the alleles are labeled as R1 (red) and R2 (white).

Alternative designations could include W1 and W2 or CW and CR, where C signifies "color," while W and R denote white and red, respectively.

Rarity of Incomplete Dominance

Clear instances of incomplete dominance leading to intermediate expression of phenotypes are relatively uncommon.

However, even when complete dominance seems evident, investigating gene product levels often reveals intermediate gene expression.

Example: Tay–Sachs Disease

Tay–Sachs disease showcases this concept well. Homozygous recessive individuals have a severe case with little to no activity of the enzyme hexosaminidase A, resulting in a fatal lipid storage disorder.

Heterozygous individuals, carrying just one copy of the mutant gene, appear phenotypically normal but demonstrate only about 50% enzyme activity compared to homozygous normal individuals.

This equal level of activity is sufficient to maintain normal biochemical function, a common scenario in enzyme-related disorders.

4.4 In Codominance, the Influence of Both Alleles in a Heterozygote Is Clearly Evident

Definition of Codominance

Codominance occurs when two alleles of a single gene produce two distinct, detectable gene products.

The joint expression of both alleles in a heterozygote is the hallmark of codominance, distinguishing it from dominance/recessiveness or incomplete dominance.

Example: MN Blood Group in Humans

The MN blood group system illustrates codominance and is characterized by the presence of an antigen (glycoprotein) on the surface of red blood cells.

Two forms of this glycoprotein exist: M and N. An individual may exhibit either one or both forms.

Control: The MN system is controlled by an autosomal locus located on chromosome 4, with two alleles designated as LM (M antigen) and LN (N antigen).

Genotype Combinations for MN Blood Group

As humans are diploid, the following three combinations of genotypes are possible:

MM (homozygous for M antigen)

NN (homozygous for N antigen)

MN (heterozygous, exhibiting both antigens)

Offspring Blood Types from Heterozygous Parents

A mating between two heterozygous MN parents can yield children with all three blood types:

MM (type M)

MN (type MN)

NN (type N)

The resulting genotypic ratio remains consistent at 1:2:1 as seen in other inheritance patterns.

Characteristics of Codominant Inheritance

Codominant inheritance is characterized by the distinct expression of the gene products of both alleles in the heterozygote.

This contrasts with incomplete dominance, where heterozygotes exhibit an intermediate, blended phenotype.

Additional Example: ABO Blood Type System

Further examples of codominance can be observed in the ABO blood type system, where alleles A and B are codominant while allele O is recessive.

The presence of both A and B antigens results in blood type AB, demonstrating codominant expression.

4.5 Multiple Alleles of a Gene May Exist in a Population

Overview of Multiple Alleles

The information stored in any gene is extensive, and mutations can modify this information in many ways, resulting in different alleles.

For any specific gene, the number of alleles within members of a population need not be restricted to two. Multiple alleles can create unique modes of inheritance and are studied in populations.

An individual diploid organism can have a maximum of two homologous gene loci occupied by different alleles of the same gene, while many members of a species may present numerous alternative forms of the same gene.

The ABO Blood Group

Observation: The ABO blood group system represents the simplest case of multiple alleles where three alternative alleles of one gene exist.

Background: Discovered by Karl Landsteiner in the early 1900s, the ABO system features antigens on the surface of red blood cells under the control of a different gene on chromosome 9. Like the MN blood group, it demonstrates codominant inheritance.

An individual can have one of four phenotypes based on these alleles:

A antigen (A phenotype)

B antigen (B phenotype)

A and B antigens (AB phenotype)

Neither antigen (O phenotype)

Allele Designation for ABO Blood Group

The genes can be symbolized as IA, IB, and i:

IA: A antigen production (dominant)

IB: B antigen production (dominant)

i: No antigen production, recessive

Phenotype Assignment

Each genotype corresponds to a phenotype in the following manner:

IA IA: Type A

IA i: Type A

IB IB: Type B

IB i: Type B

IA IB: Type AB

ii: Type O

The IA and IB alleles are dominant to the i allele and are codominant to each other, allowing for both A and B antigens to be expressed in individuals with the AB blood type.

Practical Applications

Understanding of human blood types has practical applications, particularly for compatible blood transfusions and organ transplantation.

The Bombay Phenotype

Exceptionally rare occurrences of the ABO blood type system include individuals expressing blood type O, identified in Bombay in 1952. This condition results from an incompletely formed H substance, which is an inadequate substrate for producing A and B antigens.

This phenotype is linked to a recessive mutation at a separate locus (designated FUT1), preventing synthesis of the complete H substance despite possessing the IA and/or IB alleles.

The White Locus in Drosophila

Many other traits in plants and animals are known to be controlled by multiple allelic inheritance. In Drosophila, more than 100 alleles are identified at the locus controlling eye color.

The recessive mutation causing white eyes is just one example, with the eye colors ranging from white (w) to deep ruby (wsat), orange (wa), to buff (wbf). Each allele denotes varying levels of pigmentation, leading to a spectrum of eye colors found in the fruit fly population.

4.6 Lethal Alleles Represent Essential Genes

Overview of Essential Genes

Essential genes produce gene products that are critical for an organism’s survival.

Mutations that lead to nonfunctional gene products can be tolerated in heterozygous individuals, where one wild-type allele provides enough of the essential product for survival.

Recessive Lethal Alleles

Such mutations behave as recessive lethal alleles, leading homozygous recessive individuals (i.e., having two copies of the lethal allele) to not survive.

The timing of death due to the recessive lethal allele varies; it may occur at different stages such as:

During development

Early childhood

Adulthood

Example: In mammals, a mutant allele that is a recessive lethal may lead to distinct phenotypes when present heterozygously.

Case Study: Yellow Coat in Mice

The yellow coat mutation is dominant to the normal agouti coat, resulting in yellow coats in heterozygous mice.

Homozygous yellow mice (YY) die before birth, explaining their absence.

Dominant Lethal Alleles

Oppositely, dominant lethal alleles result in the death of individuals with just one copy of the allele.

Example:

Huntington’s Disease (H): Characterized by late onset (around age 40) and results in neurodegeneration.

Affected individuals usually have already reproduced, making this allele able to persist in a population despite its lethal effects.

Population Dynamics of Lethal Alleles

Most dominant lethal alleles are rare as affected individuals often die before reproduction.

If all individuals with the dominant lethal allele die before reaching reproductive age, the allele will not be passed on and may disappear from the population unless it arises through new mutations.

Summary

Lethal alleles play a significant role in genetic inheritance by causing organismal death under specific genotypic conditions, impacting population genetics and the prevalence of certain traits in subsequent generations.

4.7 Combinations of Two Gene Pairs with Two Modes of Inheritance

Modify the 9:3:3:1 Ratio

Each example discussed so far modifies Mendel’s 3:1 F2 monohybrid ratio.

When combining two modes of inheritance in a dihybrid cross, it will modify the classical 9:3:3:1 ratio.

Mendel’s principle of independent assortment applies as long as the genes are not linked on the same chromosome.

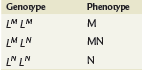

Example Case Study:

Consider a mating between two humans who are both heterozygous for the autosomal recessive gene causing albinism and both of blood type AB.

Albinism is inherited in a simple Mendelian fashion, while blood types are determined by multiple alleles, IA, IB, and i.

The probability of a particular phenotypic combination occurring among their offspring is to be determined.

Phenotypes Overview:

This dihybrid cross does not yield the classical four phenotypes following a 9:3:3:1 ratio but results in six phenotypes, yielding a ratio of 3:6:3:1:2:1.

Each phenotype’s probability is established through the forked-line method.

This illustrates the complexity and variety in the outcomes when different modes of inheritance are combined.

4.8 Phenotypes Are Often Affected by More Than One Gene

Soon after Mendel’s work was rediscovered, experimentation revealed that individual characteristics displaying discrete phenotypes are often under the control of more than one gene. This significant discovery indicated that genetic influence on the phenotype is often much more complex than Mendel had envisioned. Instead of single genes controlling the development of individual parts of a plant or animal body, it became clear that phenotypic characters can be influenced by the interactions of many different genes and their products.

Gene Interaction

The term gene interaction describes the idea that several genes influence a particular characteristic. This does not mean, however, that two or more genes or their products necessarily interact directly with one another to influence a particular phenotype. Rather, the cellular function of numerous gene products contributes to the development of a common phenotype.

Example: The development of an organ such as the compound eye in insects is exceedingly complex, leading to specific size, shape, texture, and color variations. This process exemplifies the developmental concept of epigenesis, where each developmental stage increases the complexity of the organ under the control and influence of multiple genes.

Case Study: The formation of the inner ear in mammals showcases how intricate developmental events influenced by many genes can lead to phenotypes such as hereditary deafness. Mutations interrupting these steps can lead to this common phenotype

Epistasis

Gene interaction examples often reveal epistasis, where the expression of one gene or gene pair masks or modifies the expression of another gene or gene pair.

Masking or Modification: The genes involved may control the expression of the same general phenotypic characteristic in an antagonistic manner or exert their influence in a complementary, or cooperative, fashion.

Types of Epistasis:

Homozygous recessive epistasis: Where the presence of a homozygous recessive allele prevents or overrides the expression of other alleles at a second locus.

Dominant epistasis: Where a dominant allele at one genetic locus masks the expression of alleles at a second locus.

Example of Homozygous Recessive Epistasis: The Bombay phenotype involves the homozygous presence of the mutant FUT1 gene masking the expression of IA and IB alleles in blood type determination.

Example of Dominant Epistasis: The inheritance of fruit color in summer squash demonstrates that the dominant allele A results in white fruit, regardless of the genotype at a second locus (B).

Unusual Phenotypic Ratios: Epistasis can lead to modified phenotypic ratios. For example, in a cross involving both A and B loci, the typical 9:3:3:1 ratio may be modified to 12:3:1 due to dominant epistasis affecting the distribution of phenotypes.

Complementary Gene Interaction: This can yield a modified 9:7 ratio, as seen in sweet pea flowers, where at least one dominant allele from each of two gene pairs is required to produce purple flowers.

Novel Phenotypes: Some gene interactions produce novel phenotypes in the F2 generation, generating ratios such as 9:6:1 in cases where new traits emerge alongside parental traits.

Complexity in Inheritance: The study of gene interaction reveals various inheritance patterns that modify classical Mendelian ratios. All discussed scenarios have not violated Mendel’s conclusions and maintain that both segregation and independent assortment principles apply.

4.9 Complementation Analysis Can Determine if Two Mutations Causing a Similar Phenotype Are Alleles of the Same Gene

Complementation analysis is an experimental approach used to determine whether two mutations that cause a similar phenotype are alleles of the same gene or mutations in different genes. This analysis is critical in genetic research and helps clarify the genetic basis of observable traits.

Case Study: Mutations in Drosophila (Fruit Flies)

Investigators may isolate two strains of wingless Drosophila, each demonstrating the same phenotype (wingless) due to recessive mutations.

The primary question is whether both mutations are in the same gene or in separate genes.

Experimental Method

Cross the Mutant Strains: By crossing the two strains, researchers can observe the offspring of the F1 generation to analyze the phenotype exhibited.

Possible Outcomes

Case 1: All Offspring Develop Normal Wings

Interpretation: The two mutations are in separate genes and not alleles of one another.

Complementation Occurs: Since F1 offspring are heterozygous for both genes, the normal products of both genes are produced, allowing wings to develop.

Case 2: All Offspring Fail to Develop Wings

Interpretation: The two mutations affect the same gene, meaning they are alleles of one another.

No Complementation Occurs: F1 offspring are homozygous for the two mutant alleles (ma allele and mb allele), which means no normal product of the gene is produced, leading to the failure of wing development.

Significance of Complementation Analysis

Determining Gene Involvement: Complementation analysis can be used to screen multiple mutations affecting the same phenotype to ascertain if the changes occur within a single gene or involve multiple genes.

Complementation Groups: Mutations identified to be in the same gene will fall into a complementation group and will complement mutations from other groups. This organization aids in summing up the total number of genes associated with a specific trait.

Application of the Analysis

Genetic Research: This technique is widely used in genetics to clarify complex genetic traits and to identify the genetic basis of mutations effectively.

Nobel Prize Recognition: Edward B. Lewis, a Nobel Prize-winning geneticist, played a pivotal role in establishing the methodology of complementation analysis within the field of genetics.

4.10 Expression of a Single Gene May Have Multiple Effects

Pleiotropy

Pleiotropy is the phenomenon where a single gene influences multiple phenotypic traits.

This often becomes evident when multiple effects are observed due to a mutation in a single gene.

The presence of pleiotropy means that a mutation in one gene does not affect only one trait but several, sometimes in unrelated physiological systems.

Examples of Pleiotropy in Human Genetic Disorders

1. Marfan Syndrome

Cause: Autosomal dominant mutation in the gene encoding the fibrillin protein.

Fibrillin is a connective tissue protein found in multiple tissues.

Affected Tissues:

Lens of the eye

Lining of blood vessels (e.g., the aorta)

Bones and skeletal structures

Phenotypic Effects:

Lens dislocation (eye problems)

Increased risk of aortic aneurysm (cardiovascular issues)

Unusually long limbs and fingers (skeletal abnormalities)

Historical Relevance: Some speculate that Abraham Lincoln may have had Marfan syndrome.

2. Porphyria Variegata

Cause: Autosomal dominant disorder affecting hemoglobin metabolism.

Defect: Inability to properly metabolize the porphyrin component of hemoglobin when red blood cells break down.

Physiological Consequences:

Excess porphyrins accumulate in the body, leading to toxicity, especially in the brain.

Urine appears deep red due to excess porphyrins.

Phenotypic Effects:

Abdominal pain

Muscular weakness

Fever

Racing pulse

Insomnia

Headaches

Vision problems (can lead to blindness)

Delirium and convulsions

Historical Relevance: Thought to have affected King George III of England, who exhibited all the symptoms and eventually became blind and senile before his death.

Key Takeaways

Pleiotropy demonstrates that one gene can have widespread effects on the body.

Many genetic mutations result in multiple symptoms, making it challenging to characterize disorders based on a single phenotypic trait.

Both Marfan syndrome and porphyria variegata illustrate how a single gene defect can impact multiple organ systems.

Most mutations, when closely examined, display pleiotropic effects.

4.11 X-Linkage Describes Genes on the X Chromosome

Introduction to X-Linkage

In many species, including humans and Drosophila, sex determination involves a pair of unlike chromosomes, the X and Y chromosomes.

Males (XY) have one X and one Y chromosome, while females (XX) have two X chromosomes.

The Y chromosome contains some regions that pair with the X chromosome during meiosis but is mostly genetically inert.

Many genes present on the X chromosome are absent from the Y chromosome, leading to distinct inheritance patterns known as X-linkage.

X-Linkage in Drosophila

Thomas H. Morgan's Discovery

Around 1920, Thomas H. Morgan studied white-eyed mutations in Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies).

Wild-type eye color: Red (dominant)

Mutant eye color: White (recessive)

Key Finding: Reciprocal crosses between white-eyed and red-eyed flies did not produce identical results, unlike Mendelian monohybrid crosses.

Conclusion: The gene for eye color is located on the X chromosome (i.e., it is X-linked), and its corresponding locus is absent from the Y chromosome.

Patterns of X-Linked Inheritance in Drosophila

Females (XX) have two copies of the eye color gene.

Males (XY) have only one copy of the eye color gene (on the X chromosome) and are hemizygous for X-linked genes.

Reciprocal crosses showed different results, depending on whether the white-eyed parent was male or female.

Crisscross pattern of inheritance: X-linked recessive traits are passed from homozygous mothers to all sons.

Key Terminology

Hemizygous: Males have only one copy of an X-linked gene since they possess only one X chromosome.

Crisscross pattern of inheritance: X-linked recessive genes skip generations, passing from carrier mothers to affected sons.

X-Linkage in Humans

Many human traits are X-linked and can be traced in pedigrees due to their distinctive inheritance patterns.

Example: Color blindness

Pedigree analysis shows that a carrier mother can pass the condition to all sons, but not to daughters.

Sons with the condition do not pass it to their sons but can have carrier daughters.

X-Linked Recessive Disorders

Unique Features

If an X-linked disorder is severe or lethal before reproductive age, it occurs almost exclusively in males.

Heterozygous females act as carriers, passing the mutant allele to half of their sons.

Affected males do not reproduce, limiting the disorder's spread.

Example: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD)

Cause: X-linked recessive mutation.

Symptoms:

Onset before age 6.

Progressive muscle degeneration.

Fatal by age 20.

Inheritance:

Carrier mothers pass the defective gene to 50% of sons (who develop the disorder).

50% of daughters become carriers, but they do not express symptoms.

Historical Significance of Morgan’s Work

By 1910, Morgan’s studies confirmed the chromosome theory of inheritance, first proposed in Chapter 3.

His research provided the first experimental evidence linking Mendel’s principles to chromosome behavior during meiosis.

This led to further genetic research supporting X-linkage and inheritance patterns.

Key Takeaways

X-linked genes are located on the X chromosome and follow unique inheritance patterns.

Males (XY) are hemizygous for X-linked traits, meaning they express all X-linked alleles, whether dominant or recessive.

Crisscross inheritance: X-linked recessive traits are passed from mothers to sons, skipping generations.

X-linked disorders (e.g., color blindness, Duchenne muscular dystrophy) follow a predictable inheritance pattern due to the absence of a counterpart gene on the Y chromosome.

Morgan’s research was groundbreaking in establishing the chromosome theory of inheritance, explaining how genes are passed from generation to generation.

4.12 Sex-Limited and Sex-Influenced Inheritance

Introduction

Unlike X-linked inheritance, where genes are located on the X chromosome, some autosomal genes exhibit expression patterns that are influenced by an individual's gender.

Two main types of inheritance:

Sex-Limited Inheritance: Phenotype only appears in one gender.

Sex-Influenced Inheritance: Phenotype appears in both genders but is expressed differently.

The differences in gene expression result from the hormonal environment of the individual.

Sex-Limited Inheritance

Certain autosomal genes exhibit phenotypic expression in only one sex.

Even though both males and females may carry the same genotype, the trait manifests exclusively in one sex due to hormonal influences.

Example: Feather Plumage in Domestic Fowl

The H allele (dominant) leads to hen-feathering, while the h allele (recessive) allows for cock-feathering.

Genotypes and Phenotypes:

H_ (HH or Hh) in females → Hen-feathering.

hh in males → Cock-feathering.

Key Observation: Even if a female carries the hh genotype, she will still exhibit hen-feathering due to hormonal regulation.

In some breeds:

Leghorn fowls: All individuals are hh, meaning males always show cock-feathering.

Sebright bantams: All individuals are HH, meaning males and females look the same.

Example: Milk Production in Dairy Cattle

Genes that regulate milk production are present in both males and females, but they are only expressed in females due to hormonal influence.

Sex-Influenced Inheritance

In contrast to sex-limited inheritance, in sex-influenced inheritance, a phenotype appears in both sexes, but its expression differs between males and females.

The same heterozygous genotype can lead to different phenotypic outcomes depending on the sex of the individual.

Example: Pattern Baldness in Humans

Autosomal gene with dominant and recessive interactions modified by sex hormones.

Genotypes and Phenotypes:

BB (Homozygous dominant) → Bald in both males and females.

Bb (Heterozygous):

Bald in males (due to testosterone influence).

Normal hair in females.

bb (Homozygous recessive) → Normal hair in both sexes.

Key Observation: Females can still experience thinning hair (pattern baldness) but usually much later and to a lesser extent than males.

Example: Horn Development in Sheep

Autosomal gene influences horn development, but hormonal differences cause different expressions in males and females.

Genotypes and Phenotypes:

H_ (HH or Hh) in males → Horned.

Hh in females → Hornless.

Key Observation: Males and females with the same Hh genotype display different phenotypes due to hormonal regulation.

Example: Coat Color Patterns in Cattle

Certain coat color variations are influenced by the sex of the animal, with hormones altering pigment distribution.

Key Takeaways

Sex-Limited Traits: Only one sex expresses the phenotype, even if both sexes carry the gene (e.g., milk production, plumage differences).

Sex-Influenced Traits: Both sexes can show the trait, but its expression is different or more pronounced in one sex (e.g., pattern baldness, horn development).

Hormones play a crucial role in determining how these autosomal genes are expressed in males vs. females.

Inheritance patterns may differ from classical Mendelian ratios due to their dependence on an individual's hormonal environment.

4.13 Genetic Background and Environmental Effects on Phenotypic Expression

Introduction to Phenotypic Expression

Traditionally, phenotype was assumed to directly reflect genotype.

In reality, gene expression is influenced by cellular interactions and environmental factors.

The external environment and an individual’s genetic background can modify phenotypic outcomes.

Penetrance and Expressivity

Penetrance: The percentage of individuals with a genotype who display the associated phenotype.

Example: A mutant allele in Drosophila has 85% penetrance if 85% of individuals express the mutant phenotype.

Expressivity: The degree or range of phenotypic expression for a given genotype.

Example: The recessive eyeless mutation in Drosophila shows variation from normal-sized eyes to complete eye loss.

Causes of Variation:

If a controlled environment still produces variation, genetic background is a factor.

If variation changes with external conditions, environmental factors are involved.

Genetic Background: Position Effects

Position Effect: The physical location of a gene affects its expression.

Example: If a gene is moved near heterochromatin (genetically inactive regions), its expression may be suppressed.

In Drosophila, the wild-type red-eye allele (w+) can show variegated expression if translocated near heterochromatin.

Temperature Effects and Conditional Mutations

Temperature influences phenotype:

Primrose flowers produce red petals at 23°C and white petals at 18°C.

Siamese cats & Himalayan rabbits exhibit dark fur in cooler body regions.

Temperature-sensitive mutations:

Mutations are expressed under certain temperature conditions.

Example: Some viral mutations allow normal infection at 25°C but are non-functional at 42°C.

Onset of Genetic Expression

Some genetic traits appear later in life due to developmental processes.

Examples of age-dependent disorders:

Tay-Sachs disease (autosomal recessive): Symptoms appear a few months after birth, leading to fatal neurodegeneration.

Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (X-linked recessive): Onset at 6–8 months, causing self-mutilation and neurological defects.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (X-linked recessive): Diagnosed at ages 3–5, causing progressive muscle wasting.

Huntington disease (autosomal dominant): Onset typically around age 45, leading to neurological decline.

Genetic Anticipation

Definition: A disorder’s severity increases, and its onset occurs earlier in successive generations.

Example: Myotonic Dystrophy (DM)

Autosomal dominant disorder with variable severity.

Severity correlates with trinucleotide repeat expansions in the gene.

Normal individuals have ~5 repeats, mild cases have ~50, and severe cases exceed 1000 repeats.

Similar trinucleotide repeat expansions are seen in Huntington disease and fragile-X syndrome.

Conclusion

Phenotypic expression is not solely determined by genotype; environmental factors and genetic background play crucial roles.

Understanding penetrance, expressivity, position effects, and conditional mutations helps explain variable inheritance patterns.

Many genetic disorders exhibit age-dependent expression and genetic anticipation, influencing diagnosis and research approaches.

4.14 Extranuclear Inheritance: Modifications of Mendelian Patterns

Introduction to Extranuclear Inheritance

Traditional Mendelian genetics states that phenotypes are determined by nuclear genes inherited from both parents.

However, some inheritance patterns deviate from Mendelian rules, known as extranuclear inheritance.

Extranuclear inheritance falls into two broad categories:

Organelle Heredity – Phenotypic traits influenced by genes in mitochondria or chloroplasts.

Maternal Effect – Phenotypes determined by genetic products expressed in the maternal gamete.

Early reports of extranuclear inheritance were met with skepticism, but the discovery of DNA in mitochondria and chloroplasts validated these patterns.

Organelle Heredity: DNA in Chloroplasts and Mitochondria

Before DNA was identified in these organelles, inheritance of traits was unclear but linked to cytoplasmic factors rather than nuclear genes.

Typically, transmission occurs maternally, as egg cells contribute most cytoplasm to the zygote.

Challenges in Studying Organelle Heredity:

Organelle function relies on both nuclear and organelle DNA, making mutation origins complex.

Cells contain multiple mitochondria and chloroplasts, leading to heteroplasmy (a mix of normal and mutant organelles), which can obscure mutant phenotypes.

Chloroplast Inheritance: Variegation in Four-o’clock Plants

Karl Correns (1908) studied the four-o’clock plant (Mirabilis jalapa), where leaves could be green, white, or variegated.

The white patches lacked chlorophyll due to mutations in chloroplast DNA.

Reciprocal crosses showed that leaf color was determined by the phenotype of the maternal plant.

This confirmed that chloroplast inheritance occurs through the cytoplasm and not via nuclear genes.

Mitochondrial Mutations: poky in Neurospora and petite in Saccharomyces

Mutations in mitochondria also follow extranuclear inheritance.

Mary and Hershel Mitchell (1952) discovered the poky mutant in Neurospora crassa, characterized by slow growth due to defective mitochondrial electron transport.

Crosses revealed that poky was inherited cytoplasmically, following maternal transmission.

Boris Ephrussi (1956) identified petite mutations in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), resulting in defective cellular respiration.

Most petite mutations affected mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and were maternally inherited.

Some, however, were due to nuclear mutations and followed Mendelian inheritance, demonstrating mitochondria’s dependence on both nuclear and organelle genes.

Mitochondrial Mutations in Humans: Genetic Disorders

Human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a small circular genome containing:

13 proteins essential for cellular respiration.

22 tRNAs and 2 rRNAs necessary for translation.

Why mtDNA is Vulnerable to Mutations:

Limited DNA repair mechanisms compared to nuclear DNA.

High exposure to free radicals from oxidative phosphorylation.

Heteroplasmy in humans means a mix of normal and mutant mitochondria, making inheritance patterns complex.

Example: MERRF (Myoclonic Epilepsy and Ragged-Red Fiber Disease)

Inherited maternally.

Symptoms: ataxia, deafness, dementia, seizures.

Caused by a mutation in mitochondrial tRNA gene (tRNALys), disrupting protein synthesis in mitochondria.

Heteroplasmy affects severity—cells with fewer mutated mitochondria function more normally.

Mitochondria, Human Health, and Aging

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been linked to diseases including:

Anemia, blindness, Type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s), schizophrenia, and various cancers.

Over 400 mtDNA mutations are associated with over 150 genetic syndromes.

Mitochondria and Aging:

Mutations in mtDNA accumulate over time, reducing ATP production.

Some studies link age-related muscle fiber atrophy to deletions in mtDNA.

Genetically modified mice with defective mtDNA proofreading exhibit premature aging, suggesting mitochondrial function contributes to aging.

Maternal Effect: Influence of Maternal Genotype on Offspring

In maternal effect inheritance, an offspring’s phenotype is determined by maternal nuclear genes acting before fertilization.

The developing egg stores mRNAs and proteins, which later influence early embryonic development.

Example: Embryonic Development in Drosophila melanogaster

Maternal-effect genes regulate early embryonic patterning in fruit flies.

Bicoid (bcd) gene

Encodes a protein that determines anterior (head and thorax) formation.

If a mother lacks functional bicoid (bcd-/bcd-), her offspring develop without heads and thoraxes, regardless of their own genotype.

If the mother has at least one normal allele (bcd+), the offspring develop normally.

This discovery, along with other maternal-effect genes, helped researchers understand how maternal genotype prepares embryos for development.

Conclusion

Extranuclear inheritance challenges traditional Mendelian genetics and plays a crucial role in biological inheritance.

Organelle heredity affects traits through mitochondrial and chloroplast DNA, often with maternal transmission.

Mitochondrial mutations influence human health, aging, and disease progression.

Maternal effect inheritance determines offspring phenotypes based on the mother’s nuclear genes, independent of the offspring’s genotype.

Ongoing research into extranuclear inheritance continues to uncover its implications for genetics, medicine, and evolutionary biology.

5.1 X and Y Chromosomes and Sex Determination

Introduction to Sex Determination

Sex determination has long been a subject of interest among geneticists. The discovery of sex-linked chromosomal structures led to a deeper understanding of how biological sex is established in various organisms. The early 20th-century research of Hermann Henking, Clarence McClung, and Edmund B. Wilson provided significant insights into this process.

Hermann Henking’s Discovery of the X-Body (1891)

Henking identified a unique nuclear structure in the sperm of certain insects, which he called the X-body.

His work laid the foundation for future studies on sex chromosomes.

Clarence McClung’s Heterochromosome Hypothesis (Early 1900s)

McClung observed that some sperm in grasshoppers contained an unusual chromosomal structure called a heterochromosome, while others lacked it.

He incorrectly associated the presence of the heterochromosome with the development of male offspring.

Edmund B. Wilson’s Clarification (1906)

Wilson studied the butterfly Protenor and demonstrated that female somatic cells contained 14 chromosomes, including two X chromosomes (XX).

During oogenesis, an even reduction occurs, producing gametes with seven chromosomes, including one X chromosome.

Male somatic cells had only 13 chromosomes, consisting of one X chromosome and an overall different chromosomal count.

During spermatogenesis, males produced two types of sperm:

One with six chromosomes (lacking an X chromosome)

One with seven chromosomes, including an X chromosome.

Fertilization Outcomes:

If an X-bearing sperm fertilized an egg, the offspring would be female (XX).

If an X-deficient sperm fertilized an egg, the offspring would be male (XO).

This mechanism ensured a 1:1 sex ratio in the species.

Wilson’s Studies on the Milkweed Bug (Lygaeus turcicus)

In Lygaeus turcicus, both males and females have 14 chromosomes:

12 autosomes (A)

2 sex chromosomes (XX in females, XY in males)

Female gametes always carry (6A + X).

Male gametes are produced in equal proportions:

(6A + X)

(6A + Y)

Random fertilization ensures an equal number of male and female progeny.

Heterogametic vs. Homogametic Sex

Males in Protenor and Lygaeus species produce two different types of gametes, making them the heterogametic sex (XO or XY).

Females produce uniform gametes, making them the homogametic sex (XX).

Alternative Systems of Sex Determination

The heterogametic sex is not always male. In certain organisms, the female produces unlike gametes.

Some species exhibit either Protenor XX/XO or Lygaeus XX/XY modes of sex determination but with the female being heterogametic.

Examples:

Moths

Butterflies

Some fish, reptiles, and amphibians

Birds (e.g., chickens)

A plant species (Fragaria orientalis)

To distinguish such cases, geneticists use the ZZ/ZW notation:

ZZ = Homogametic male

ZW = Heterogametic female (e.g., birds, where females determine the offspring’s sex).

Conclusion

The discovery of sex chromosomes revolutionized the understanding of sex determination. The differentiation between homogametic (XX or ZZ) and heterogametic (XY, XO, or ZW) sex determination systems explains the genetic basis behind the 1:1 sex ratio seen in many species. These foundational studies paved the way for modern genetics and reproductive biology.

5.2 The Y Chromosome Determines Maleness in Humans

Discovery of the Human Chromosome Number

Early efforts to determine the human diploid chromosome number were challenging due to the large number of chromosomes.

In 1956, Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan developed an effective technique to accurately view chromosomes, confirming the human diploid number as 46.

Later that year, C. E. Ford and John L. Hamerton confirmed this finding using testicular tissue.

Karyotypes revealed a difference in the sex chromosome composition between males and females:

Females: XX

Males: XY

Role of the Y Chromosome in Sex Determination

The presence of the Y chromosome determines maleness.

Several alternative explanations were considered, including:

The Y chromosome might play no role.

Two X chromosomes might determine femaleness.

Maleness might result from the absence of a second X chromosome.

The correct conclusion was drawn from studying sex chromosome variations such as Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) and Turner syndrome (45,X).

Klinefelter Syndrome (47,XXY)

Affects 1 in 660 male births.

Characteristics:

Male genitalia and internal ducts but small testes.

Many are sterile due to low sperm count.

Some feminine development, such as gynecomastia (breast enlargement) and rounded hips.

Intelligence is usually normal, but some may remain unaware of the condition until seeking infertility treatment.

Additional variations exist, including 48,XXXY, 48,XXYY, 49,XXXXY, and 49,XXXYY, with more severe symptoms.

Turner Syndrome (45,X)

Affects 1 in 2000 female births.

Characteristics:

Female external genitalia but underdeveloped ovaries.

Short stature, webbed neck, and broad chest.

Normal intelligence but may have learning difficulties.

Some individuals are mosaics (e.g., 45,X/46,XX or 45,X/46,XY), leading to varied symptoms.

Many 45,X fetuses do not survive to birth, explaining its lower incidence compared to Klinefelter syndrome.

Other Sex Chromosome Aneuploidies

47,XXX (Triple-X Syndrome): Affects 1 in 1000 female births.

Usually normal but may have sterility or mild cognitive issues.

Rare cases of 48,XXXX (Tetra-X) and 49,XXXXX (Penta-X) with more severe symptoms.

47,XYY Syndrome: Affects about 0.1% of males.

Tall stature is a consistent trait.

Early studies suggested a link to aggression and criminal behavior, but later research showed that most XYY males live normal lives.

Sexual Differentiation in Humans

Early Embryonic Development:

By the fifth week of gestation, the embryo has bipotential gonads, capable of developing into either ovaries or testes.

Two sets of undifferentiated ducts:

Wolffian ducts → Male reproductive system.

Müllerian ducts → Female reproductive system.

The presence of a Y chromosome triggers male development.

If the Y chromosome is absent, the gonadal ridges develop into ovaries.

If the Y chromosome is present, testes develop around the seventh week.

By the twelfth week in females, oogonia begin meiosis and remain dormant until puberty.

Males do not produce sperm until puberty.

The Y Chromosome and Male Development

The Y chromosome was once thought to contain few genes but is now known to have at least 75 genes, compared to 900–1400 genes on the X chromosome.

Pseudoautosomal Regions (PARs):

Found at both ends of the Y chromosome.

Share homology with the X chromosome, allowing synapsis and recombination during meiosis.

Male-Specific Region of the Y (MSY):

Comprises 95% of the Y chromosome.

Contains genes specific to male development.

Sex-Determining Region Y (SRY) Gene:

Located near the short arm of the Y chromosome.

Encodes testis-determining factor (TDF), which initiates testes formation.

Evidence for SRY's Role:

Some XX males carry an SRY gene attached to an X chromosome.

Some XY females lack the SRY gene.

Transgenic experiments in mice confirm that SRY triggers male development.

Paternal Age and Y Chromosome Mutations

Paternal Age Effects (PAE):

Older fathers have an increased risk of passing mutations to offspring.

Associated with autism, schizophrenia, and certain cancers.

Studies show mutations accumulate in sperm over time.

Conclusion

The presence of the Y chromosome and the SRY gene is essential for male development.

Klinefelter syndrome, Turner syndrome, and other sex chromosome anomalies provide crucial evidence for the Y chromosome’s role in sex determination.

SRY gene functions as the master switch, directing the development of the male reproductive system.

Without a Y chromosome, the default pathway leads to female development.

5.3 The Ratio of Males to Females in Humans Is Not 1:1

Sex determination in humans follows the segregation of X and Y chromosomes during meiosis. Since males are heterogametic (XY), they produce two types of sperm—50% carrying X and 50% carrying Y. If fertilization occurs randomly and both sexes have equal viability, a 1:1 sex ratio is expected. However, real-world observations show a deviation from this ratio.

Sex Ratios in Humans

The sex ratio, or the proportion of males to females, is measured in two ways:

Primary Sex Ratio (PSR) – Ratio of male to female conceptions.

Secondary Sex Ratio (SSR) – Ratio of male to female births.

Worldwide data show that the SSR is slightly above 1.0, meaning more males are born than females. In 1969, the U.S. Caucasian SSR was 1.06 (106 males per 100 females), which declined to 1.05 by 1995. Other populations show variations, such as 1.025 in African Americans and 1.15 in Korea.

Investigating the Primary Sex Ratio

Although more male births occur, it was uncertain whether more males were conceived or if prenatal female mortality was higher. A 1948 study of miscarriages and abortions suggested that male fetal mortality was higher, yet estimates of the PSR for U.S. Caucasians still suggested more males were conceived (PSR ≈ 1.079).

Examining the Assumptions

Researchers explored three key assumptions regarding sex ratio balance:

Equal Production of X- and Y-Bearing Sperm – Assumed due to chromosome segregation.

Equal Viability and Motility of Both Sperm Types – No strong evidence suggests differences.

Equal Egg Receptivity to X- and Y-Bearing Sperm – No confirmed bias.

Despite these assumptions, male births consistently exceed female births, indicating external factors influence the sex ratio.

Recent Findings and Reassessment

A 2015 study using assisted reproductive technology challenged previous assumptions. It found that the PSR is closer to 1.0, meaning equal numbers of males and females are conceived. However, differential prenatal mortality—where more females die during early development—results in more male births, explaining the observed SSR imbalance.

5.4 Dosage Compensation Prevents Excessive Expression of X-Linked Genes in Humans and Other Mammals

Introduction to Dosage Compensation

In humans, females have two X chromosomes while males have one X and one Y chromosome.

This difference could lead to a dosage imbalance in X-linked gene expression.

If unregulated, females might produce twice the amount of X-linked gene products compared to males.

Dosage compensation mechanisms exist to balance gene expression between sexes.

Barr Bodies

Discovery:

Identified by Murray L. Barr and Ewart G. Bertram in cats.

Later confirmed in humans by Keith Moore and Barr.

Characteristics:

Barr body = Inactivated X chromosome.

Found in female cells (e.g., buccal mucosa, fibroblasts).

Condensed, dark-staining structure (~1 mm in diameter) attached to the nuclear envelope.

Stains positively with DNA-binding dyes.

Mechanism:

Suggested by Susumu Ohno.

Only one X chromosome remains active, ensuring equal gene dosage in males and females.

Barr Body Rule (N-1 Rule):

The number of Barr bodies = Total X chromosomes - 1

Examples:

Turner syndrome (45,X): No Barr bodies.

Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY): One Barr body.

Triple-X syndrome (47,XXX): Two Barr bodies.

Tetra-X syndrome (48,XXXX): Three Barr bodies.

Implications of X Inactivation

Challenges to Dosage Compensation:

Turner syndrome (45,X) individuals exhibit abnormalities despite having only one X chromosome.

Extra X chromosomes in 47,XXX and 48,XXXX individuals still lead to clinical effects.

Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) individuals exhibit symptoms despite X inactivation.

Possible Explanations:

Incomplete early-stage inactivation: Inactivation may not occur in early gonadal development.

Partial gene escape: ~15% of genes on inactivated X chromosomes remain active.

Critical gene dosage effects: Despite inactivation, some genes are still expressed in excess, leading to developmental issues.

The Lyon Hypothesis

Proposed by Mary Lyon, Liane Russell, and Ernest Beutler (1960s).

Key Concepts:

Random X Inactivation: Either the maternal or paternal X is randomly inactivated.

Early Developmental Timing: Inactivation occurs during the blastocyst stage.

Clonal Propagation: All descendant cells maintain the same X inactivation pattern.

Experimental Evidence:

Mice heterozygous for X-linked coat color genes: Patchy pigmentation (mosaic pattern) due to X inactivation.

Calico and tortoiseshell cats: X-linked coat color genes result in distinct patches.

G6PD Enzyme Study in Humans: Female fibroblast clones express only one of two enzyme forms.

Red-green color blindness in humans: Female carriers show mosaic retinas with mixed defective and normal patches.

Mechanism of X Chromosome Inactivation

Epigenetic Silencing:

Inactivated X chromosomes undergo modifications.

Changes occur in DNA and histone proteins, leading to gene silencing.

Memory mechanism ensures continued inactivation through cell division.

This process is a form of genetic imprinting.

X-Inactivation Center (Xic):

Located at the proximal end of the p arm on the X chromosome.

Contains regulatory elements controlling inactivation.

The X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) gene is crucial for inactivation.

Role of XIST RNA:

Transcribed but not translated.

Coats the X chromosome that will be inactivated.

Initiates chromatin modifications to silence gene expression.

Other Regulatory Genes:

Tsix (Antisense to XIST): Helps regulate XIST.

Xite: Plays a role in X inactivation.

Experimental Evidence for XIST Function:

Brockdorff and Penny (1996) demonstrated that deleting XIST prevents X inactivation.

Result: The chromosome lacking XIST remains active, proving its essential role.

Conclusion

Dosage compensation ensures balanced X-linked gene expression in males and females.

Barr bodies and the Lyon hypothesis explain the mechanisms of X inactivation.

Despite inactivation, some genes escape silencing, leading to genetic syndromes.

The XIST gene is a critical regulator of X inactivation, confirming the epigenetic control of gene expression.

Key Terms to Remember

Dosage Compensation – Balancing gene expression between sexes.

Barr Body – Inactivated X chromosome.

Lyon Hypothesis – Random X inactivation.

X-inactivation Center (Xic) – Regulates X inactivation.

XIST Gene – Produces RNA that inactivates one X chromosome.

Mosaicism – Different X chromosome inactivation in different tissues.

5.5 The Ratio of X Chromosomes to Sets of Autosomes Can Determine Sex

Overview

In some organisms, sex determination is not dependent on the presence of a Y chromosome but rather on the ratio of X chromosomes to autosomal sets.

This mechanism is observed in Drosophila melanogaster (fruit flies) and Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworms).

Sex Determination in Drosophila melanogaster

Key Discovery by Calvin Bridges (1921)

Found that the Y chromosome does not determine maleness in Drosophila.

Sex is determined by the ratio of X chromosomes to sets of autosomes (X:A ratio).

Nondisjunction Studies

Nondisjunction: Failure of chromosomes to separate properly during meiosis.

Resulting sex chromosome compositions:

XXY flies → Normal females

XO flies → Sterile males

Conclusion: Y chromosome lacks male-determining factors but is essential for male fertility.

Triploid (3n) Female Studies

Triploid (3n) females: Have three sets of autosomes and three X chromosomes.

Meiosis in triploid females produces various chromosomal constitutions in offspring.

Results led to the development of the Genic Balance Theory.

Genic Balance Theory

Sex is determined by the X:A ratio, not by the presence of the Y chromosome.

Key Ratios and Their Outcomes:

1.0 (XX:2A, 3X:3A) → Normal fertile females

>1.0 (3X:2A = 1.5) → Metafemales (often inviable)

0.5 (XY:2A, XO:2A) → Normal and sterile males, respectively

<0.5 (XY:3A = 0.33) → Metamales (infertile)

Intermediate (e.g., X:2A = 0.67) → Intersex individuals with both male and female characteristics

Key Genes in Drosophila Sex Determination

Transformer (tra) gene: An autosomal gene that influences sex determination.

Mutations cause females to develop as sterile males.

Sex-lethal (Sxl) gene: X-linked “master switch” gene for female development.

Activated when X:A = 1.0 → Leads to female differentiation.

Inactive when X:A = 0.5 → Male differentiation occurs.

Doublesex (dsx) gene: Final regulator of sexual differentiation.

Alternative splicing of dsx transcript determines male or female development.

Sex Determination in Caenorhabditis elegans

Two Sexual Phenotypes

Males (only testes)

Hermaphrodites (testes & ovaries; capable of self-fertilization)

Reproductive Process

Hermaphrodites store sperm in larval development and later produce eggs.

Most offspring are hermaphrodites, with <1% developing as males.

Males can mate with hermaphrodites, producing 50% male and 50% hermaphrodite offspring.

X:A Ratio Determines Sex

C. elegans lacks a Y chromosome.

X:A Ratio Outcomes:

1.0 (XX:2A) → Hermaphrodites

0.5 (X:2A) → Males

Key Takeaways

Drosophila and C. elegans rely on the X:A ratio for sex determination rather than the presence of a Y chromosome.

The Y chromosome in Drosophila is needed for male fertility but does not dictate maleness.

C. elegans completely lacks a Y chromosome, yet still has distinct sexes based on X:A ratio.

Sex determination is controlled by regulatory genes such as Sxl, tra, and dsx in Drosophila.

Alternative RNA splicing plays a significant role in the regulation of sexual differentiation.

5.6 Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination (TSD) in Reptiles

Introduction to TSD

Unlike genetic sex determination (GSD), where sex is determined by sex chromosomes, some reptiles rely on environmental factors, particularly temperature.

This phenomenon is known as temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD).

Common in all crocodiles, most turtles, and some lizards.

In contrast, other reptiles such as snakes and certain lizards follow genetic sex determination (XX/XY or ZZ/ZW systems).

Three Patterns of TSD

Researchers have identified three distinct TSD patterns, shown in Figure 5.9:

Case I: Low incubation temperatures result in 100% females, while high temperatures produce 100% males.

Case II: Low temperatures yield males, and high temperatures produce females (opposite of Case I).

Case III: Both low and high temperatures produce females, while intermediate temperatures produce males in varying proportions.

These patterns differ across species:

Some crocodiles, turtles, and lizards follow Case III.

Other reptiles exhibit Case I or Case II.

Key Observations About TSD

In all three cases, specific temperature ranges result in both male and female offspring.

The pivotal temperature (Tₚ) is the range at which sex determination occurs, typically spanning only 1–5°C.

Small fluctuations in incubation temperature can significantly affect the sex ratio of the population.

Role of Hormones in TSD

The physiological mechanism behind TSD involves steroids, particularly estrogens, and the enzymes responsible for their synthesis.

Aromatase, a crucial enzyme, converts androgens (male hormones like testosterone) into estrogens (female hormones like estradiol).

During gonadal differentiation:

High aromatase activity leads to ovary development (females).

Low aromatase activity results in testis development (males).

Researchers, including Claude Pieau and colleagues, propose that thermosensitive factors regulate the transcription of the aromatase gene, thus influencing sex determination.

Broader Implications of Hormonal Influence

Similar mechanisms involving sex steroids are found i n other non-mammalian vertebrates, including birds, fish, and amphibians.

Estrogens play a crucial role in sex differentiation across multiple species beyond reptiles.