Physics waves internal

The Physics Behind the Violin: A Study of Sound Production and Acoustics

Introduction

The violin is one of the most expressive and versatile string instruments, widely used in various musical traditions. Its ability to produce a wide range of tones and dynamics stems from the principles of physics that govern wave motion, resonance, and acoustics. This report explores the underlying physics of the violin, focusing on how it produces sound, the role of resonance, and the impact of different materials and construction on its acoustics.

Research Question

How do wave properties and acoustic principles contribute to sound production in the violin?

Hypothesis

The violin produces sound through forced vibrations that generate standing waves in the strings. These waves interact with the body of the instrument through resonance, amplifying specific frequencies. Constructive and destructive interference, reflection, transmission, absorption, and scattering all contribute to the overall timbre and projection of the violin’s sound.

Sound Production in the Violin

The violin produces sound when a bow is drawn across the strings, causing them to vibrate. The fundamental physics concept at play here is forced vibration, which occurs when an external force (the bow) continuously drives the oscillation of an object (the string). The friction between the bow and the string adheres momentarily before slipping, creating a periodic "stick-slip" motion. This generates a complex waveform composed of a fundamental frequency and harmonics.

The frequency of the sound depends on three main factors:

Tension (T) of the string: Higher tension increases frequency.

Linear density (μ) of the string: Heavier strings vibrate at lower frequencies.

Length (L) of the vibrating section: Shorter string lengths produce higher frequencies.

The fundamental frequency (f) of a vibrating string is given by the equation:

This equation explains why violinists alter pitch by pressing down on the strings to shorten the vibrating length.

Wave Properties and Interference

The sound waves produced by the violin exhibit key wave properties:

Frequency (f): The number of oscillations per second, measured in hertz (Hz), which determines the pitch.

Amplitude: The height of the wave, which corresponds to the loudness of the sound.

Wavelength (λ): The distance between two consecutive peaks or troughs.

Speed (v): The rate at which the wave propagates through a medium.

Period (T): The time taken for one complete oscillation, given by .

When waves from different sources interact, superposition occurs, leading to constructive and destructive interference:

Constructive Interference: When two waves of the same frequency and phase meet, their amplitudes add together, resulting in a louder sound. This is crucial in the violin when the vibrations of the strings reinforce the vibrations of the body, enhancing sound projection.

Destructive Interference: When two waves of opposite phase meet, they cancel each other out, reducing amplitude. This occurs in areas where sound waves from different sources interfere destructively, affecting tone quality.

Beats: When two waves of slightly different frequencies interfere, they create periodic variations in loudness known as beats. This is relevant in tuning the violin, as musicians listen for beat frequencies to fine-tune their strings to match precise pitches.

Resonance and the Violin Body

Resonance is the tendency of a system to oscillate at larger amplitudes at specific frequencies, known as natural frequencies. The wooden body of the violin serves as a resonator, amplifying the vibrations.

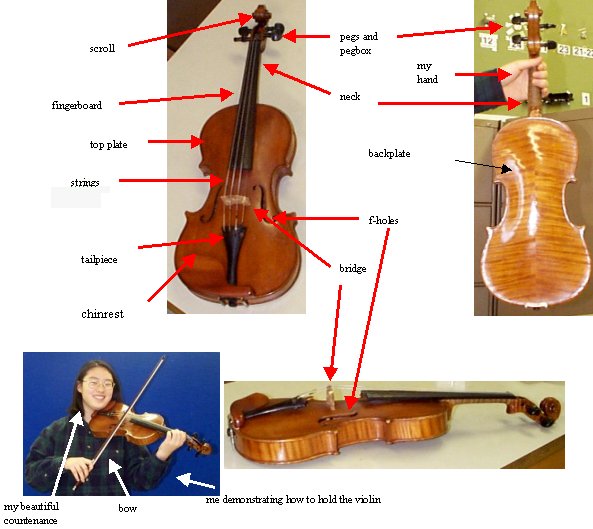

The bridge transmits vibrations from the strings to the soundboard (top plate), which then vibrates and transfers energy to the air cavity inside the violin.

The f-holes in the body shape the resonance and allow air to move in and out, influencing sound projection.

The back plate and ribs also contribute to sound production by vibrating in response to the energy from the soundboard.

The violin’s resonance frequencies depend on the design and materials used. Each component vibrates at its own natural frequencies, reinforcing specific harmonics.

Absorption, Reflection, Transmission, and Scattering of Sound Waves

As sound waves travel through and around the violin, they undergo different interactions:

Absorption: Some energy is lost as heat within the wooden structure, affecting sustain and tonal warmth.

Reflection: The curved surfaces of the violin reflect waves internally, reinforcing certain frequencies and shaping the instrument’s tone.

Transmission: Some energy passes through the body, affecting how sound is projected into the surrounding air.

Scattering: Uneven surfaces and f-holes cause scattering, contributing to the violin’s unique timbre by diffusing certain frequencies in various directions.

Harmonics and Timbre

The violin produces not just the fundamental frequency but also a series of overtones, known as harmonics. The harmonic series follows:

where is an integer representing the harmonic number.

Timbre refers to the quality or color of a sound, which is shaped by the balance of harmonics. Different bowing techniques (e.g., pizzicato, sul ponticello, and sul tasto) emphasize different harmonics, altering the timbre. The variation in harmonic content gives the violin its distinctive warm and rich sound.

Material Science and Its Impact on Acoustics

The materials used in violin construction significantly affect its sound quality. Traditional violins use spruce for the top plate (lightweight and strong) and maple for the back plate (denser for better resonance). The elastic modulus, density, and damping coefficient of the wood determine how effectively the instrument transmits and sustains vibrations. Modern violins sometimes incorporate carbon fiber to enhance durability and resonance properties.

Discussion and Analysis

The violin's sound production relies on multiple wave interactions and acoustic properties:

The stick-slip motion of the bow creates standing waves in the strings.

The superposition principle leads to constructive and destructive interference, affecting the richness of sound.

Resonance in the violin body enhances certain frequencies, improving sound projection.

Wave behaviors like reflection, transmission, and scattering influence how the violin produces its distinctive timbre.

Understanding these principles helps violin makers optimize their designs for better sound projection and tonal quality. It also allows musicians to manipulate sound through bowing techniques and material choices.

Conclusion

The violin is a perfect example of applied physics in music. By understanding the principles of wave motion, resonance, interference, harmonics, and material science, we can appreciate the instrument’s ability to produce its characteristic sound. Advancements in materials and construction continue to refine violin acoustics, making it an ever-evolving subject of study in physics and engineering.

References

Rossing, T. D. (2010). The Science of String Instruments. Springer.

Fletcher, N. H., & Rossing, T. D. (1998). The Physics of Musical Instruments. Springer.

MAIN FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENT: Create and Resonate (Hopefully Pleasant) Sound Waves

DESIGN PARAMETER: Simple harmonic oscillator (in the form of a violin, of course)

GEOMETRY/STRUCTURE:

|

Figure 0: Major Components of A Violin |

|

Figure 1: Schematic of Violin Model Components |

EXPLANATION OF HOW IT WORKS/ IS USED:

Okay, some basics. It’s pretty obvious that the source of the sound in a violin has something to do with the strings and the body, which resonates the sound made by the strings. The idea is that by plucking, bowing, or hitting a string, a violinist can make it vibrate. (Hitting is fairly rare, but it can be done; in one bowing stroke, col legno, you do hit the string with the wooden part of the bow.) In this paper, I will concentrate on the plucking, because the physics for bowing and hitting are similar. The vibration resonated from the string and the body excites the air molecules around the violin, creating a wave that we perceive as sound.

DOMINANT PHYSICS:

The String

The vibration (and therefore the sound) is affected by three main variables:

The tension of the string. At the end of the violin is the pegbox, where the pegs are (duh!). The strings are wound around the peg, and so the tension in the string can be changed when the pegs are loosened or tightened.

The more tension, the higher the frequency of the vibration (and therefore, the higher the pitch).

The length of the string. While the length of all of the strings on a violin are about the same, the actual length of the vibrating part can be changed, by putting one’s fingers down and making the string length effectively shorter. Another way that we can see how string length changes the sound is through comparisons with other stringed instruments: the length of the strings on a viola are longer than those on a violin, so we would expect a lower sound. And that is precisely how it is.

The shorter the length of the string, the higher the frequency.

The mass per unit length. This really isn’t a true variable, because a violinist can’t actually change it. In plain English, the "mass per unit length" is just how thick the strings are. On a violin, the E-string is thinner than the A-string, and that’s just how it is; no amount of wishing will cause it to be otherwise. However, an A-string on a cello will be much thicker, causing a lower sound. (Actually, that isn’t the only reason; the two variables described above also play a part.)

The thinner the string, the higher the frequency.

The Body

No, I’m not talking about the new governor from Minnesota (my home state, by the way), I’m talking about the rest of the violin. Think about it: have you ever played with an electric guitar when the amplifier is off? Plucking the strings only gives off a rather pathetic twang. Because the vibration caused by plucking a string is relatively "small," not very many air molecules are excited. What we need, therefore, is something that can act as a resonator.

The strings rest on the bridge, which transfers the vibrations down to the body of the instrument. The violin resonates in two main ways:

The top and back plate. These plates radiate most of the sound.

Air circulating within the violin. This resonance is not nearly as important as the one mentioned above.

Modes ‘n’ Nodes

Variable | Description | Metric Units | English Units |

m | mode | -- | -- |

n | node | -- | -- |

L | Length of string | m | ft |

D | Distance from the site of the plucking to the bridge | m | ft |

T | Tension | N (kg m s-2) | lbf |

M | Mass per unit string length | kg m-1 | lb ft-1 |

v | velocity | m s -1 | ft s-1 |

F | frequency | Hz (s-1) | Hz (s-1) |

l | wavelength | m | ft |

Instruments have very separate, distinct sounds, called "timbres" in music lingo. When you listen to the radio or go to the symphony, it is usually easy to pick out the various instruments, since an oboe (hopefully) sounds nothing like a tuba. These different timbres are caused by harmonics. Each instrument has a specific pattern of harmonics, which create the unique sound. In this section, I will try to explain how a violin’s harmonics are created.

Have you ever seen the high school physics demonstration where the teacher gets someone to hold one end of a rope and then frantically waves the other end up and down? In the middle of the rope, if the demonstration goes well, you can see a "node," which is a point on the string which doesn’t move. Sometimes, by waving even more frantically (i.e. higher frequency), the teacher can create three or four nodes.

|

Figure 2: Relation Between Nodes and Modes |

You may very well be wondering, "well, what does all this have to do with the violin?" Well, a violin string works on the same sort of principle. Because it is vibrating so fast (the frequency is high), many nodes can be created (See Figure 2 above).

When a string is plucked in the middle, all of the even modes will be still (See Figure), while all of the odd modes will oscillate furiously. However, this isn’t what usually happens when one plays the violin: usually, the string is played close to one end. In this case, some modes will be more excited than others. We can find which modes are completely still, by using an equation with a pretty interesting relationship:

Non-Excited Modes = m (L / D) ( Equation 1)

Ta-dah! This relationship is important because of how modes are related to sound; the equation tells us which modes don’t vibrate (and therefore, which do). The excited modes give off distinct frequencies, and the combination of which frequencies are present and to what extent they are present (their amplitude) gives the distinct timbre of the violin. The equation for the frequency is given by:

fn = (n / 2L) (T / M)1/2 (Equation 2)

This equation is just a glorified version of the standing wave equation:

fn = (nv / 2L) (Equation 3)

Derivation:

f = v/l l = 2L (the wavelength is 2L because the wave travels up and back down the string)

fn = (nv / 2L) v=(T/M)1/2 (the units work out: ( (kg m s-2) / (kg m-1 ) )1/2 = m s-1 )

fn = (n / 2L) (T / M)1/2

Anyway, a given note on a violin will have several frequencies vibrating at once. This distinct combination creates the uniquely beautiful timbre of the violin.

LIMITING PHYSICS:

Ideally, the violin string doesn’t move, the material is constant throughout, and it has no bending stiffness. However, we know that this is impossible, given the inconsistent quality of natural materials. (Although it is interesting to note that most violinists prefer to use gut strings, not synthetic ones, showing that sometimes nature does know what it’s doing.) More interesting are debates on how the body of the violin affects the resonance capabilities. If, for instance, a violin’s top plate is too thick, the sound will be muted. If it is too thin, the sound will be "boomy." But we all know that the most limiting factor of how good a violin sounds is simply the level of the person playing.

Knowt

Knowt