Chapter 7: Geographies of Culture and Landscape

A World Divided by Culture?

- Humans differ from all other forms of life in that they have developed not only biologically but culturally; largely limited to biological adaptation, they have become so highly specialized that most are restricted to particular physical environments; which has resulted in species extinction in many cases.

- Humans have an ability first to analyze and then to change the physical environments that we encounter.

- Unlike animals, humans can form ideas out of experiences and act on the basis of these ideas; we are capable of not only changing physical environments but also changing them in directions suggested by experience.

- The world we live in features tremendous cultural diversity, but it also, has increasing interaction between cultures. As a result, in many areas traditional groups are struggling to protect their established ways of life against “foreign” influences; in others, the frequently uncontrolled passions that surround language, religion, and ethnicity are erupting in cultural and sometimes political conflicts. Ironically, our culture has been responsible for both erecting barriers and sparking conflict between peoples.

- ==Why has culture tended to have the unfortunate consequences?==

- Our world is divided, mainly due to differences in culture.

- By culture, we mean the human ability to develop ideas from experiences and subsequently act on the basis of those ideas.

- One task humans may choose to tackle is to create new sets of values - in effect, to re-engineer ourselves.

Formal Cultural Regions

- Geographers are mainly concerned mainly with human impact on natural landscape due to their cultural differences mainly.

- %%For determining cultural regions four main points are to be focused%%

- Criteria for inclusion, that is, the defining characteristic.

- Date or time period (since these regions change over time).

- Spatial scale

- Boundary lines

World Regions

- Historian A.J. Toynbee (1935–61), classified these cultures into

- Abortive and surviving.

- Some as “arrested” because of their overspecialized response to a difficult environment; left them unable either to expand into different regions or to cope with environmental change.

- Some as; Western Christendom, Orthodox Christendom, the Russian offshoot of Orthodox Christendom, Islamic culture, Hindu culture, Chinese culture, and the Japanese offshoot of Chinese culture - (named after religion).

- And the most important feature as; manner in which it has responded to the environment.

- The first geographers to attempt to determine boundaries of world regions were Russell and Kniffen (1951); who began by recognizing various cultural groups and then related them to areas so as to recognize seven cultural regions, each a product of a long evolution of human–land relations. With the addition of one “transitional” area, these regions effectively cover the world. Russell and Kniffen’s regions are well justified, and their classification is a valuable contribution to our general understanding of the world. Still, it is important to emphasize that world regionalizations of this type do not represent the best use of the culture concept in geography. The problem is scaptial scale;

- The larger the area to be divided, the more likely it is that the regions identified will be either too numerous or too superficial to be helpful.

- Like regionalizations based on physical variables, cultural regionalizations are more appropriately seen as useful classifications than as insightful applications of geographic methods.

- Cultural regions and the distinctive landscapes associated with them are more effectively considered on a more detailed scale. (As an example North America is on of the regions, we find that further subdivision greatly enhances our appreciation of the relationship between culture and landscape.

North American Regions

Is relatively easy to subdivide because the development of its contemporary cultural regions is recent enough that we are able to trace their origins.

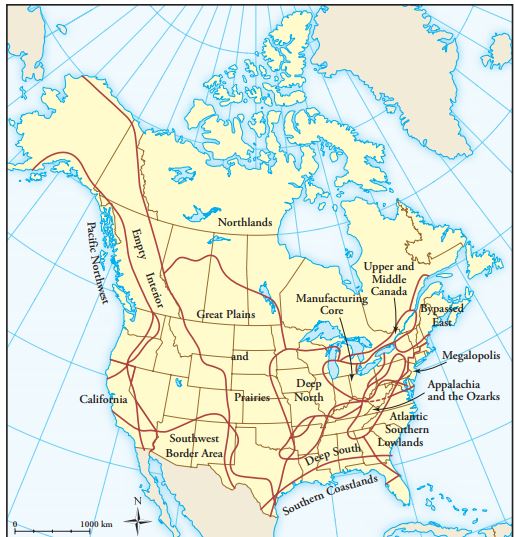

In the map above the illustrator has clearly shows different regions of North America, conveys the “feeling” of each region in their discussions. This regionalization is interesting because it focuses on broad regional themes rather than on specific criteria and recognizes that the border between the United States and Canada is not a fundamentally geographic division.

Vernacular Cultural Regions

- Regions, and the landscapes that characterize them, are not simply locations; but they are places in the sense that they convey a purpose. The purpose that a place has is a human meaning, dependent on social matters.

- Humans, as members of groups, create places; in turn, each place created develops a character that affects human behaviour.

- Our experience of place and the meaning we attach to it are not simply individual matters they are shared thoughts for example home; as many people share home. It can be characterized as two mixed feeling; topophilia and topophobia.

- These terms refer to the emotional attachment that exists between person and place, so that the feelings are related to certain characteristics of both the individual and the environment.

- Individual characteristics include personal well-being and familiarity with place.

- Environmental characteristics include the attractiveness of places as judged by individuals.

- Vernacular region %%can formally defined as the region perceived to exist by those living there and/or by people elsewhere. Such regions are most clearly characterized by a sense of place.%%

Vernacular Regions in North America

- North American geographers have delimited many vernacular regions, typically by collecting information on individual perceptions.

- In short of all surveys; North America was better understood as a collection of nine nations, places that are full of meaning but that do not appear on any map.

- One of the surveys of Joel Garreau invites the reader to consider how North America really works and notes that each nation is characterized by a particular way of looking at the world.

Regional Identity

- Vernacular regions are not simply locations: they are places.

- The name of the region conveys a meaning. Parts of the world possess such a powerful regional identity that the mere mention of the name conjures up vivid mental images.

- For example, most North Americans, regardless of religious affiliation, recognize that the term ’Holy Land’ refers to the land bordering on the eastern Mediterranean.

- Also; other places have one meaning for one group and a quite different meaning for another. Such as for country-music lovers, Nashville is likely the home of the Grand Ole Opry; for others it may be simply the capital of Tennessee.

The Making of Cultural Landscapes

- All cultures share certain basic similarities—all need to obtain food and shelter and to reproduce—they differ in the methods used to achieve those goals.

- As humans settle they get closely associated to physical environment.

- Over time; %%cultural adaptations brought increasing freedom from environmental constraints.%%

- Gradually, as humans’ ties to the physical environment loosened, their ties to their culture increased.

- One of the most important changes in human history was the shift to a capitalist mode of production, which largely destroyed our ties to the physical environment but created a new set to culture.

- Some human geographers see this change as part of an ongoing process of diffusion that is effectively homogenizing world culture by minimizing regional variations.

Cultural Adaptation

- As humans settled the earth, different cultures evolved in different locations. Despite their many underlying similarities, each developed its own variations on the basic elements of culture: language, religion, political system, kinship ties, and economic organization.

- As we seek to understand how different cultures create different landscapes, we must also ask how sound relationships develop between humans and their physical environment. To get this answer we should first understand the concept of cultural adaptations.

- As humans are adapting continuously to their environment and surrounding; Cultural adaptation may take place at an individual or group level. Human geographers are interested in both - consists of changes in technology, organization, or ideology of a group of people in response to problems, whether physical or human. Such changes help us to deal with problems in any number of ways, such as by permitting the development of new solutions or by improving the effectiveness of old ones and by increasing general awareness of a problem or by enhancing overall adaptability. In short, cultural adaptation is an essential process by which sound relationships evolve between humans and land.

- Also includes changes in attitudes as well as behaviour. One main example of our attitudinal change is our increasing awareness of the importance of environmentally sensitive land-use practices; an example of behavioural change is the implementation of such practices. Needless to say, behavioural changes do not always accompany attitudinal changes—or even follow them.

- Human geographers have proposed a number of concepts to explain more precisely what cultural adaptation is and how it works. Following are different point of views:

- First, in their analysis of the evolution of agricultural regions, it is suggested that; cultures are particular beliefs, psychological mindsets, that result in a culturally habituated predisposition towards a certain activity and hence a certain cultural landscape.

- %%Second, a cultural group moving into a new area may be pre-adapted for that area; conditions in the source area are such that any necessary adjustments have already been made prior to the move or are relatively easy to make thereafter.%%

- %%Third, and the most important point of view, a cultural region or landscape can be divided into three areas%%

- Core (the hearth area of the culture),

- Domain (the area where the culture is dominant),

- And sphere (the outer fringe),

- And cultural identity decreases with increasing distance from the core.

Cultural Diffusion

- %%Can be best described as the process of spread in geographic space and of growth through time.%%

- Migration can be regarded as a form of diffusion, although the term is more often used in the context of some particular innovation, such as a new agricultural technique.

- Diffusion research has a rich heritage in geography and has been associated with three approaches: cultural geography, spatial analysis, and political economy.

Cultural Geographic Emphasis

- Typical studies focused on the diffusion of certain material landscape features, such as housing types, agricultural fairs, covered bridges, place names, or grid-pattern towns. The usual approach was to identify an origin and then describe and map diffusion outwards from it.

- Various issues emerged from this research. In many cases, debate centred on the question of single or multiple invention, the numbers and locations of hearth areas, or the problem of determining source areas for agricultural origin and subsequent diffusion.

Spatial Analytic Emphasis

- The exact interests of researchers were quite different from those of cultural geographers working in the Sauerian landscape school tradition, the central concern was unchanged: to study diffusion as a process effecting change in human landscapes.

- Importance of chance factors was explicitly acknowledged by Hägerstrand in his use of a procedure known as Monte Carlo Simulation, which allowed for the likelihood of any given acceptance of an innovation to be interpreted as a probability.

- Spatial analysis–oriented diffusion research and introduced a number of themes that we might call empirical regularities because they are consistently observable in geographic analyses.

A Political Economy Emphasis

- Represents an example of the dehumanizing approach that is characteristic of the spatial analysis.

- After 1970, a third approach to diffusion research was developed, focusing not on the mechanics of the diffusion process but on the human and landscape consequences of diffusion.

- Any diffusion process adds up to existing technological capacity, but it affects the use of resources in some way. For example, some innovations result in significant time savings and hence change individuals’ daily time budgets; others actually demand more time, as in the case of the introduction of formal schooling. Analyzing such innovations means analyzing cultural change.

- Recent research into innovation diffusion also considers the extent to which there may be a spatial pattern of innovativeness related to a wide range of social variables such as relative wealth, level of education, gender, age, employment status, and physical ability.

- In a study in Kenya, it was discovered that the diffusion process could be greatly affected by the pre-emption of valuable innovations by early adopters.

Language

- %%Most important aspect in understanding people and their landscapes.%%

- %%As people moved across the earth, different languages developed in areas offering new physical environmental experiences.%%

- %%It is a cultural variable, a learned behaviour which helped humans evolve and communicate.%%

- Its usefulness in delimiting groups and regions.

- The death of a language is seen as the death of a culture. It is for this reason that such efforts have been made to ensure the continuity, or even revival, of traditional languages.

- It is commonly seen as a fundamental building block of nationhood, language is of particular interest to human geographers concerned with the minority groups and their relationship with nationalism.

- History shows much less interaction between the two groups within each region, is due to language barrier.

- It concerns its interactions with environment, both physical and human. Spatial variations in language are caused in part by variations in physical and human environments, while language is an effective moulder of the human environment.

- Language gives a group identity.

How Many Languages?

- %%Language was a single entity later it was branched into different languages representing different cultures.%%

- Many languages were arisen and many were dried out.

- Roughly 7,000 languages; approx. 1000 have disappeared.

- About 96% of the world’s population speak only 4% of the world’s languages.

Disappearing Languages

- Two reasons for disappearance

- Language with few speakers tends to be associated with low social status and economic disadvantage, so those who do speak it may not teach it to their children.

- Globalization depends on communication between previously separate groups, it is becoming essential for more and more people to speak a major language such as English or Chinese.

- Due to this; 2,500 are in danger of extinction, with about 1,000 of these seriously endangered.

- Reactions to disappearance

- To some it represents culture loss and is just as serious a threat as loss of biodiversity.

- This is because in some languages some words can’t be translated.

- Loss of languages is also an important practical issue because most languages include detailed knowledge—about local environments and culture and lifestyle of people living in the era.

- Others see the loss of linguistic diversity as a sign of increasing human unity.

- Spread of languages

- Migration

- When people find that speaking a particular language is benefit to their economic.

- Language is associated with a culture that is in some way impressive, perhaps in military, artistic, economic, or religious terms.

Classification and Regions

- As human groups moved, their language altered, with groups that became separated from others experiencing the greatest language change.

- Interesting feature of spread of languages is, temperate areas of the world have relatively few languages with many speakers, whereas tropical areas have many languages with relatively few speakers. One reason for this distribution is that agriculture spread throughout temperate areas, leading to the resultant emergence of large-scale societies that gradually replaced smaller groups.

- Counting languages is difficult, but we can estimate that Europe has about 200, the Americas about 1,000, Africa about 2,400, and the Asian-Pacific region about 3,200.

Language and Identity

- Language is the %%primary base for identity.%%

- A common language facilitates communication; different languages create barriers and frictions between groups, further dividing our divided world.

Language and Nationalism

- For many people, the language they speak is a result of power struggles for cultural and economic dominance.

- Is the basic of determining a nation

- A common language facilitates communication.

- It is such a powerful symbol of “groupness” that it serves to proclaim a national identity where it is needed.

Multilingual States

- Examples Switzerland, Belgium and Canada.

Minority Language

- A language without official status typically experience a slow but inexorable demise.

- Minority-language speakers strive often for preservation of their language; they may press for the creation of their own separate state, using the language issue as justification.

Communications b/w Different Language Groups

- In parts of East Africa, Swahili is an official language; combining the local Bantu with imported Arabic, it is an example of a ‘lingua franca’, a language developed to facilitate trade between different groups (in this case, Africans and Arab traders).

- Southeast Asia, where ‘pidgins’ are usually based on English, with some Malay and some Chinese. A pidgin that becomes the first language of a generation of native speakers is known as a ‘creole’.

Language and Landscape

Naming Places

- %%We name places due to two reasons%%

- In order to understand and give meaning to landscape - landscape without names is like individuals without names.

- Naming places probably serves an important psychological need—to name is to know and control, to remove uncertainty about the landscape.

- Nam%%es usually combine two parts, generic and specific.%%

- Newfoundland, for example, has ‘Newfound’ as the specific component and ‘land’ the type of location being identified as the generic component.

- Analysis of place names can provide information about both the spatial and the social origins of settlers.

- Place names typically date from the first effective settlement in an area.

- Place names can be an extremely valuable route to understanding the cultural history of an area. This is especially clear in areas where the first effective settlement was relatively recent but is also the case in older settled areas.

Renaming Places

- Renaming occurs because previous names may now cause offence.

Landscape in Language

- Not only is language in landscape capable of making landscape, but landscape is also in language. This is because physical barriers tend to limit movement, there is a general relationship between language distributions and physical regions.

- Vocabulary of any language necessarily reflects the physical environment in which its speakers live; for example there are many Spanish words used for features of landscapes.

- As languages move to new environments, new words are added to help describe these new environments.

Religion

- The %%universality of religion suggests that it serves a basic human need or reflects a basic human awarenes%%s.

- Recent research suggests that the traditional understanding of the rise of civilization, namely, that plant and animal domestication set the scene for organized religion and political systems.

- A religion consists set of beliefs and associated activities that are in some way designed to facilitate appreciation of our human place in the world.

- In many occasions; religious beliefs generate sets of moral and ethical rules that can have a significant influence on many aspects of behaviour, such as core set of beliefs on rituals, everyday behaviour, symbols, and, of course, landscapes.

- Numerically Christianity is the leading religion, followed by Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

- In the word 13-15% of population is atheist (non-religious).

- Religions get further divided into competing branches with different beliefs and practises.

- These divisions arose as religions moved through landscapes, coming into contact with different cultural contexts which brought up new understandings.

- Many cultures embraced a form of animism—in which a soul or spirit is attributed to various phenomena, including inanimate objects—especially before the diffusion of universalizing religions, notably Christianity and Islam.

Origins and Distribution of Ethnic Religions

Hinduism

- Evolved in the lowland area of north India about 2000 BCE - is the first major religion in this area to develop.

- This religion has evolved in the region of India the most during the past few hundred years.

- Ongoing evolution of Hinduism means it might be better described as a variety of related religious beliefs rather than as a homogeneous religion.

- it was brought up to other parts of world but didn’t retain significant numbers of adherents outside India. This means Hinduism is associated with India and is broadly defined with its culture.

- It is polytheistic religion and has close ties to the rigid social stratification of the caste system.

Judaism

- First monotheistic religion, - originated about 2000 BCE in the North East indian areas.

- Contains significant internal divisions reflecting theological and ideological differences

- Differences developed as Jews moved, with Sephardic Judaism concentrated in Spain and Ashkenazic Judaism elsewhere in Europe.

- Sephardic Jews easily adapted to different areas, but Ashkenazi Jews tended not to integrate with larger non-Jewish, Christian society. This lack of integration was undoubtedly a twofold process, with Jews wishing to maintain their traditions and with Christians being antagonistic towards Jews.

Origins and Distribution of Universalizing Religions

Buddhism

- Was the first universalizing religion - offshoot of Hinduism founded in the Indo Gangetic hearth by Prince Gautama.

- But after death of Prince Gautama it was spread by missionary monks into other parts of India and then throughout much of Asia.

- In the first few centuries of religions birth, it evolved two new versions of it

- Mahayana Buddhism - Upper Indus Valley

- Theravada Buddhism - Sri Lanka

- By the third century, some scholars claim, buddhist scriptures were systemized, that the religion was effectively the state religion of a large India-wide empire, and that it was then carried to China after about 100 BCE and then throughout most of Asia.

- Mahayana version is more inclusive, and it diffused north from India into Central and East Asia (including China, Korea, Japan, Tibet and Mongolia).

- While Theravada version moved across Southeast Asia, including Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

- Anyhow Buddhism had no influence over China as a religion; as both Taoism and Confucianism wielded important influences.

- Only Thailand and Burma had influence of Buddhism as a state religion.

Christianity

- Developed about 600 years after Buddhism as an offshoot of Judaism.

- Began when disciples of Jesus of Nazareth accepted that he was the expected Messiah.

- Religion spread slowly during his lifetime and more rapidly after his death as missionaries carried it initially to areas around Jerusalem and then through the Mediterranean to Cyprus, Turkey, Greece, and Rome.

- Local variations soon appeared, these never assumed the same significance as was evident in Hinduism and Buddhism. This was because Christianity included the idea of a unified Church, because written details of the founding of the religion were soon available as the four gospels, and because there were deliberate efforts to formalize universal doctrines at a series of councils.

- Spread rapidly through the Roman Empire and was formally adopted as an official religion.

- However, the collapse of the empire and resultant political fragmentation created competing Germanic and Roman influences, with many Germanic people practising a version of Christianity known as Arianism.

- Christianity has proven to be the most influential religion in shaping the world because it was carried overseas by European colonial powers and it has been very adaptable and therefore effective at encouraging converts.

Islam

- Arose in the Arabic Mesopotamian area; it is related to both Judaism and Christianity but has additional Arabic characteristics.

- Islam is an all-encompassing world view, shaping both group and individual attitudes and behaviours.

- Founded by Muhammad, born in Mecca in 570, the religion had diffused throughout Arabia by the time of his death in 632.

- Further diffusion was rapid as a result of Islamic political and military expansion.

- Arab Muslims stretched to west including parts of northern Mediterranean as far as Spain and much of North Africa and east to include Afghanistan, Pakistan,Iraq Iran and some parts of India..

- Limited expansion of Islam into Europe resulted in conflicts with Christians; in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there was a massive expulsion of Muslims from Spain, with many relocating in North Africa

- Islam has not received same degree of divisiveness as other universalizing religions. But the most notable division of in Islam is Sunni and Shia. These divisions came in after the death of last Prophet of Allah; Muhammad.

- Sunni - believed that umma (community of muslims) were responsible for electing Muhammad’s successor.

- Shia - while believed that Muhammad had designated a specific person (his cousin and son in-law).

- Sunnis, who represent about 90 per cent of the current Muslim population, dominate in Pakistan and in Bangladesh mainly; Shiites are a majority in Iran and Iraq. For most of the history of Islam, the Shiite–Sunni divide has been peaceful, at least partly because the two groups usually occupied different places.

- Is frequently considered a religion of the Middle East, today’s largest Muslim populations are in Indonesia, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

- Islam is not as adaptable as Christianity to some, as Muslims see their religion as a way of life that encompasses social and political affairs; meaning that it is well-suited to some societies but not to others.

- Is a more prescriptive religion than Christianity as it comprises a universal code of behaviour that adherents accept and pursue. The body of Islamic law, the shariah, serves as a basis for the religion and the political state.

Religion, Identity, and Conflict

- A person’s sense of identity and community, can often be closely tied to religion.

- Religions have competed, directly or indirectly, with each other and with different versions of the same religion as they have spread from source areas and become established in particular places.

- In fact such such competitions has sometimes resulted in conflict and expulsion of the members of one group.

- Our human tendency to identify with a specific religion has given rise to many military conflicts, such as recent conflicts in Pakistan (Muslim–Hindu), Lebanon (Christian– Muslim), and Northern Ireland (Catholic–Protestant Christian.

- In some cases, religion promotes mistrust of non-believers, an attitude that, combined with a general lack of understanding, may lead to hostility and conflict.

Religious Landscapes

Religion and landscape are often inextricably interwoven, for three principal reasons:

- Beliefs about nature and about how humans relate to nature are integral parts of many religions.

- Many religions explicitly choose to display their identity in landscape.

- Members of religious groups identify some places and load them with meaning these are called sacred spaces.

Religious Perspectives on Nature

- Judaism and Christianity place God above humans and humans above nature.

- Eastern religions in general, see humans as a part of, not apart from, nature and both as having equivalent status under God.

- Religious beliefs about human use of land, plants, and animals can have significant impacts on regional economies.

- Different religions incorporate different beliefs and attitudes, and what is important to one group may not be important to another. Such as;

- The pig is a common domesticated animal in Christian areas but absent in Islamic and Jewish areas.

- Hindus regard cows as sacred animals that are not to be consumed but, Muslims consume and slaughter them as a Holy ritual.

Religious Displays of Identity in Landscape

- Landscape is a natural repository for religious creations, a vehicle for displaying religion.

- Sacred structures, in particular, are a part of the visible landscape.

- Hindu temples are intended to house gods, not large numbers of people, and are designed accordingly.

- By contrast, Islamic mosques are built to accommodate large congregations of people, as are Christian churches and cathedrals.

- Islamic mosques, they don’t use the conventional seating of Christian churches so they can accommodate many more people in the same amount of space, thus require larger parking lots outside the building.

- Size and decoration of religious buildings often reflect the prosperity, as well as the piety or devotion, of the local area at the time of construction.

- When religious buildings are built in a area, where religion is newly brought; people might take it as threat to their traditions and religion.

- Religious identity can be displayed by the way of dressing such as

- Sikh and Orthodox men can be identified by their code of dress and their beards.

- Muslim women can be identified by veil or hijab while muslim men can be identified with a prayer cap.

- Christians with crosses.

- Hindus are marked on the forehead.

Religion and Sacred Spaces

- Religiously recognized holy lands

- Israel for Jews,

- All of India for some Hindu fundamentalists,

- Saudi Arabia (Mecca and Madinah) for muslims,

- Palestine for Christians.

- Many religions attribute a special status to certain features of the physical environment. Such as;

- River Ganges for Hindus,

- Mount Fuji in Shintoism,

- and others.

- Sacred places such as mosques, temples, shrines, and others attract many tourists.

- In some respects culturally based divisions between groups and places are being reduced as part of the cultural globalization; it is clear that some linguistic and religious differences are potent divisive forces in the contemporary world.

- As a matter of fact; some religious differences are playing increasingly critical roles in global political life, especially because of the increasing popularity of fundamentalist interpretations of some major religions.

- It is of note that some places are highly contested because they are understood to be sacred by two or more religious groups. This causes conflicts related to the ownership of such places.