Chapter 3: Morphology II

1. Representing Word Structures

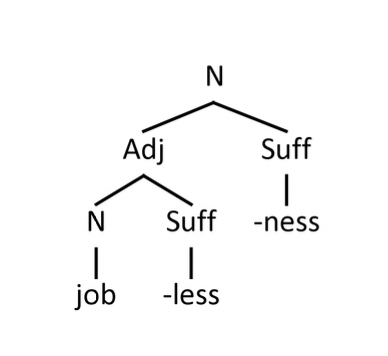

So far, we have been using hyphens (-) to separate morphemes in a very linear fashion. The internal structure of words can also be represented using morphological trees (also known as word trees). For instance, if we were to represent the word joblessness in a tree, we would draw the following structure (note that ‘Suff’ stands for suffix and ‘Pref’ stands for prefix):

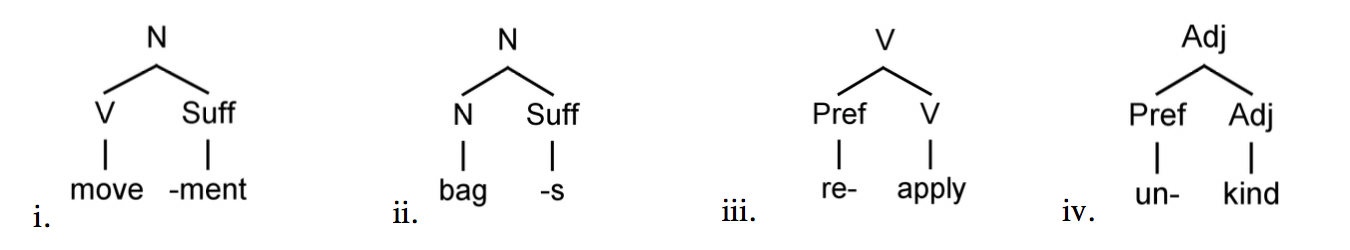

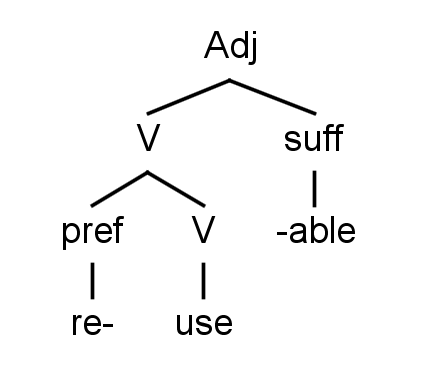

Additional examples of word structures are provided below:

Before we dive into ways of illustrating internal word structure, let’s review some of the concepts covered in Chapter 2. In the previous chapter, we learned that words containing only one morpheme are called free morphemes. Simple words such as red, fly, and cup are free morphemes that have a syntactic category (noun, verb, etc.). Since simple words contain only one morpheme, we do not typically draw their internal structure.

Now, when we look at complex words made up of only two morphemes, we need to remember two facts about affixation: 1. affixes (bound morphemes) attach to very specific kinds of bases. For example, the suffix -able prefers attaching to verbs and not nouns or adjectives. -ish on the other hand attaches to nouns and some adjectives, but never to verbs.

a. doable, playable, readable, not blueable, matable

b. pinkish, selfish, boyish, not typeish, readish

2. Derivational affixes can change the syntactic category of a word they attach to words ending with -able become adjectives while words ending with -ment or -ness are nouns. These two facts will be our guidelines in determining how words with more than one affix are formed.

Let’s consider a few examples of complex words. First, it is important to identify the root of the complex words you are dealing with. Once you identify the root, you should find all the affixes attaching to it. In the case of words that have multiple suffixes (or prefixes) attaching to the root, remember that the element closest to the root attaches first.

The word immunities, for example, consists of the root immune and two suffixes -ity and -s. Since -ity is a derivational affix, it attaches to the root immune first. If the plural -s could attach to adjectives, *immune-s-ity would result in an ungrammatical word as plural -s is an inflectional affix. Inflectional affixes attach last!

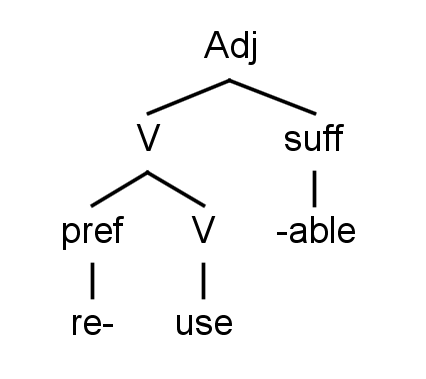

Now, let’s look at a more interesting example – the word reusable. At this point, we might consider there being two trees possible since both reuse and usable are existing English words!

(a) One possible morphological tree for the word reusable.

(b) Alternative morphological tree for the word reusable.

What do we know about the affixes re- or -able? In the word reusable, the prefix re- freely attaches to verbs to create new verbs: reform, redo, reread. On the other hand, -able attaches to verbs resulting in adjectives (signable, transportable, and so on). Most importantly, re- does not attach to adjectives and cannot create words such as reblue, reshort, or *rehappy.

Since reusable contains two affixes, the morphological tree will require multiple levels of structure, just as we have seen in the immunities example above.

The correct morphological tree for reusable.

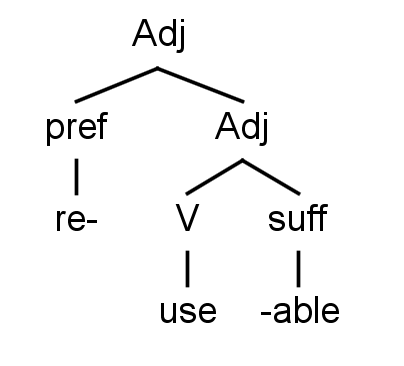

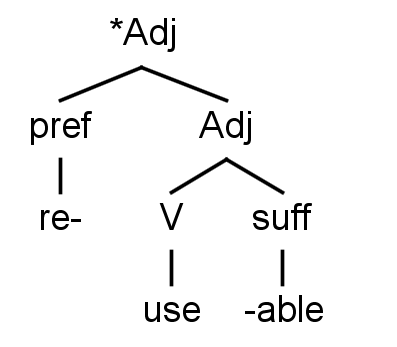

The structure above will be the only possible way to analyze the word. The prefix re- must attach to the root use first since re- attaches to verbs. The suffix -able attaches to the base reusein order to form reusable, an adjective. We know that if we attach -ablefirst, we will create an adjective that blocks the possibility of re- attaching (*rehappy, *retall). Thus, the morphological tree below is not possible:

Impossible morphological tree for reusable.

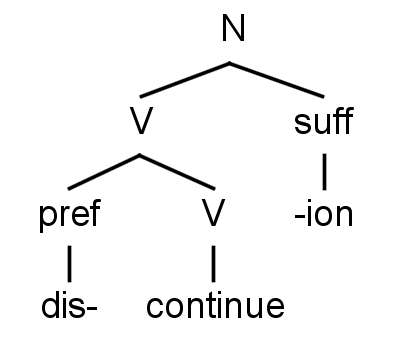

Let’s look at another example of a complex word made up of a root and two affixes. Consider the word discontinuation. Does dis- attach first to form discontinue? Or does -ion attach first to form continuation? Both discontinue and continuation are existing English words, so what do we do?

The key to determining which order of attachment is correct involves the fact that dis- (meaning opposite of, do the opposite of) freely attaches to verbs but not nouns. We cannot create words such as disknowledge, distable, or *distruth. On the other hand, -ion (also written as -ation and -tion) attaches to verbs and creates nouns (construction, protection, and so on). If we attach -ion first, we will create a noun, meaning that dis- will not be able to attach. By this logic, dis- will attach to continue first because it cannot attach to nouns (like continuation).

Morphological tree for the word discontinuation.

By providing evidence of the morphological breakdown of reusable and discontinuation, we see that words containing more than one affix have a hierarchical word structure. This structure reflects the order in which affixes attach. We want to note that historically, many English words come from languages such as Latin and Greek and can be broken down into smaller meaningful units. However, most English speakers would not be able to analyze these words any further and would consider them free morphemes.

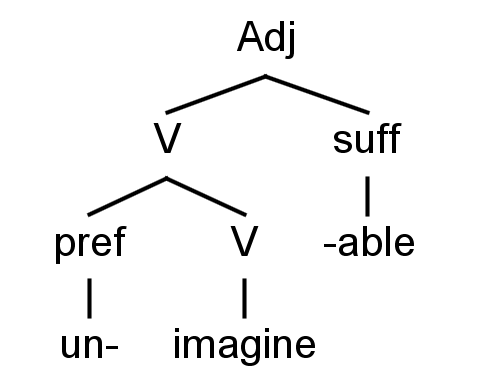

The following morphological tree for the word unimaginable is correct:

1.1 Morphological Ambiguity

In previous sections, we looked at internal structures of unambiguous words. Usually, words contain a single meaning that allows us to derive a single morphological tree. There are, however, also structurally ambiguous words. These words have multiple meanings (typically two) which reflect the possibility of drawing more than one morphological tree.

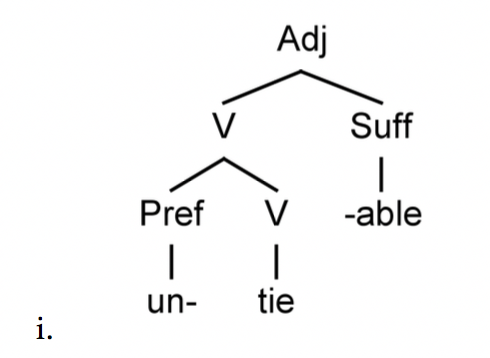

A common example of a structurally ambiguous word is untieable. Words such as untieable have two meanings which are a direct result of the ways in which morphemes combine. Let’s look at the two affixes attaching to the root tie (V): un- and -able. Un- carries a reversive meaning and attaches to verbs (only if the action is reversible). Un- can also be a negating prefix that attaches to adjectives. The suffix -able attaches to verbs and denotes the ability to do something. Since the root tie is a verb, we can attach the prefix un- to form untie and later attach -able to form the adjective untieable as shown in (i).

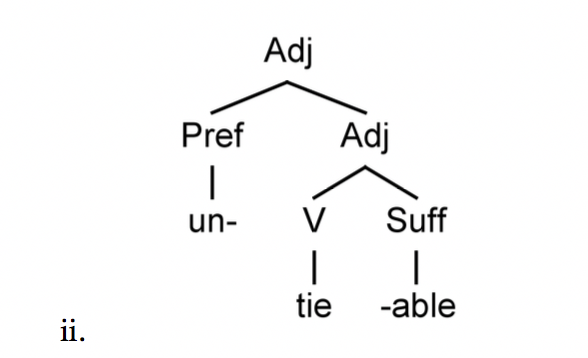

The second derivation is the opposite of the tree above: the suffix -able attaches to the root to produce the adjective tieable. Since the negating prefix un- can attach to adjectives, we end up with untieable as seen in (ii).

The meaning of (i) is significantly different from the meaning of (ii):

(i) ‘able to untie’; I can undo my shoelaces because they are untieable. = [untie [-able]]

(ii) ‘unable to tie’; I can’t tie my shoelaces because they are wet. They are untieable! = [un- [tieable]]

2. Derivation: Word Formation Processes

In the previous chapter, we saw a process called affixation by which an affix (or multiple affixes) attaches to form new words or add grammatical function. Derivational affixation is one of the most common word formation processes in English, as well as other languages. We can create a further distinction by specifying the kind of affix that was attached: for example, English has derivational prefixation (if a prefix is attached) and derivational suffixation (for suffixes). By adding a derivational affix to a base, we can create a multitude of words that have new meanings or syntactic categories. For instance, we can use the prefix un- to create negated (opposite) meanings of adjectives: happy – unhappy, pleasant – unpleasant, bearable – unbearable, and so on. However, derivational affixation is not the only way for English speakers (and speakers of other languages) to create new words! In the following sections, we will discuss a few other processes that can create new words or take existing words and change their meanings.

2.1. Compounding

Compounding is a very common process by which we create new words in English. Compounding involves joining together two existing words into a new unit. Normally, two free morphemes join to form a compound. For example, speakers of English know that green house in a sentence like My neighbour built a green house is different from the meaning of greenhouse in My neighbour built a greenhouse. In the first example, green house means any house that is painted green. In the second example, greenhouse refers to a specific type of enclosed structure used for growing plants. Syntactically, we can also say that in the first example, green functions as an adjective. In the second, greenhouse is a single unit that is a noun.

Most of the time, the resulting compounds belong to one of the following syntactic categories: noun, adjective, adverb, or verb. A few examples include parking ticket (N), force-feed (V), carsick (Adj), and downward (Adv). There are examples of compound prepositions as well (e.g., without), and prepositions can be parts of other compounds (e.g., outsource, which is a preposition + verb). Notice that for most compounds in English, the rightmost element determines the syntactic category of the entire compound. A parking ticket is a noun since the rightmost morpheme ticket is a noun. The same applies to force-feed and carsick; feed in this context is a verb while sick is an adjective. The element that determines the syntactic category of a compound is known as its head. In English, the head of a compound is usually on the right side of the compound. That is why we call English a right-headed language. Other languages might be left-headed, with the left-most element determining the compound’s syntactic category.

Additionally, the formation of compounds is not limited to two morphemes, allowing multiple compounds to combine into larger words:

(1) Train station, Train station exit, South train station exit

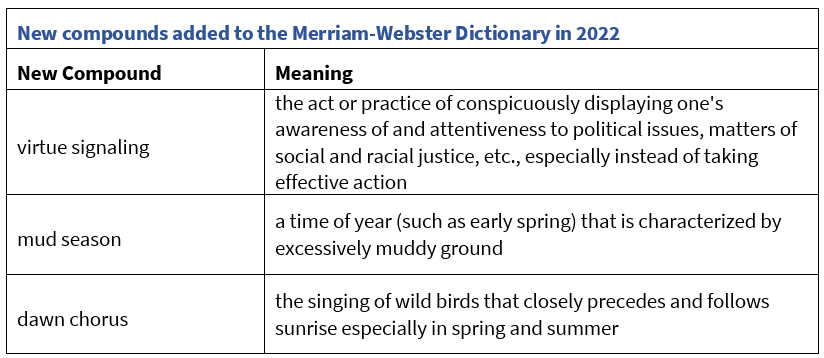

Compounding is a very productive word creation process that facilitates the expansion of our dictionaries at incredibly short intervals. Below are a few compounds the Merriam-Webster Dictionary added in September of 2022. You might notice that many of these compounds have been a part of the English language for many years prior to being added to the dictionary.

2.1.1 Properties of Compounds

Compounds are written in a multitude of ways, sometimes being represented with a hyphen (-), as a single word or as separate words. The pronunciation of compounds, however, is very different from that of separate words. Typically, the stress (i.e., emphasis or loudness) falls on the first element of the compound whereas in non-compound word combinations the stress usually falls on the second element. For instance, the compound greenhouse, meaning a glass-enclosed structure, receives the stress on the adjective green. Meanwhile, the expression green house, meaning a house that is green in colour, stresses the noun house.

2.1.2 Endocentric and Exocentric Compounds

Compounds are additionally classified based on the meaning they convey to the speaker. Endocentric compounds tend to relay meaning that is related to the head of the compound. These compounds have transparent, predictable meanings. For instance, an earthworm is a type of worm and self-care is a type of care.

In other cases, the meaning of the compound is not directly derived from its head. Boldface is not a type of face, but a typeface made with thick strokes. Similarly, a bluebell is not a type of bell but a flower. Compounds with meanings that are not obvious or predictable are called exocentric.

2.2 Reduplication

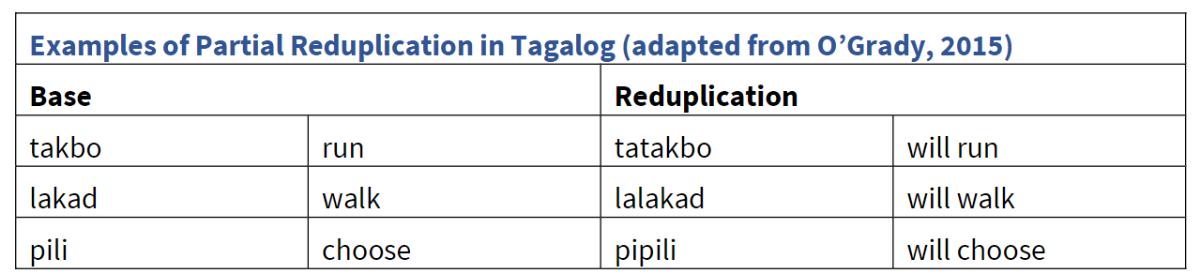

Another word formation process that can denote grammatical or semantic contrast is called reduplication. Reduplication involves copying a free morpheme or a part of it to create new words. There are two basic types of reduplication: partial reduplication involves repeating a part of the morphological base. This can be a sound or a syllable. Partial reduplication is seen in Tagalog, which copies the first consonant-vowel cluster of the base:

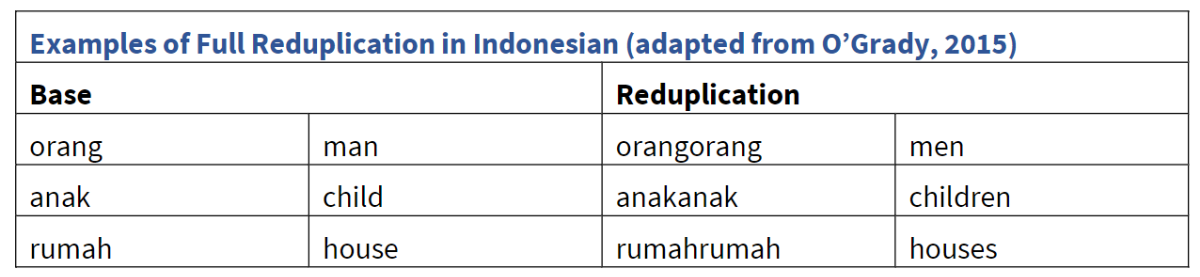

Additionally, languages utilize full reduplication by copying the entire morpheme to change meaning. Indonesian is a language that uses full reduplication to mark plurality as seen below:

English does not use reduplication in productive ways (to create new words), however, there are some recent developments like food-food in I want food-food and blue-blue in The sky was blue blue to denote intensity or focus on the literal meaning of an object. While some languages use reduplication to derive new words, many languages like Tagalog and Indonesian use reduplication (either full or partial) as a means of showing grammatical information (i.e., inflection).

2.3 Zero Derivation

Zero derivation or conversion {The change of a word’s syntactic category without changing its form, e.g., Google (N) becoming Google (V) as in, to Google a fact} is a process that allows a language to assign a new syntactic category to an already existing word. Since zero derivation changes the syntactic category of the word, it is considered to be a type of derivation process that does not involve affixation. Some of the more recent conversions include Google(N) – to Google (V), inbox (N) – to inbox (V), and Skype(N) – to Skype (V).

Some conversions involve a change of stress, although these patterns vary from dialect to dialect:

a. Verbs: transfer, convert, commune, permit

b. Nouns: transfer, convert, commune, permit

Question 3.7

Review

Search a dictionary like the Merriam-Webster Dictionary and give an example of a word that has undergone zero derivation. (Use an example other than Google, Inbox, and Skype.)

Your Answer

The word "call" has gone through zero derivation. The word "call" is a verb and a noun according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

2.4 Clipping

A process which shortens a multisyllabic word by deleting one or more syllables is called clipping. Names are a common product of this process, resulting in names such as Rob, Kat, and Liz.

Typically, the first syllable is selected to become the new form: fan from fanatic, bio from biology, and app from application. However, this is not always the case: flu from influenza and mum from chrysanthemum.

Other languages also use clipping. Here is an example from German: Mathe from Mathematik ‘math’ and Bus from AutoBus ‘bus’.

2.5 Blending

Blending creates new words from parts of already existing words, typically from the first part of the first word and the final part of another word. Some of the most common blends include brunch from breakfast and lunch, motel from motor and hotel, and smog from smoke and fog. A more recent addition to the dictionary includes the blend sponcon, which is a blend of sponsored and content.

2.6 Backformation

Backformation is a process that creates new lexical entries by removing a supposed morpheme from an already existing word. It is nearly impossible to tell which words are created through backformation unless we research the history of these words! For example, donate was originally formed by removing the supposed suffix -ion from the noun donation. Donation came into English from French donacion. Although the English word ends in -ion, it is not equivalent to the English suffix -ion which creates nouns from verbs. Nonetheless, speakers of English unconsciously analyzed donation as ending in -ion and backformed the verb donate. In English, words ending in the suffix -er or -or are also susceptible to backformation where nouns such as editor become misanalyzed to form verb forms like edit.

2.7 Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronyms are created by taking the first letters of the words in a phrase and pronouncing them as a word. Examples of acronyms include NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization), and BOGO (buy one, get one). Acronyms can become so ingrained in a language that speakers may no longer know what the letters stood for: laser (light amplification by the stimulated emission of radiation), radar (radio detecting and ranging), and scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus).

Initialisms, also known as abbreviations, contrast acronyms as they are pronounced as a string of letters rather than a complete word. Initialisms include USA (United States of America), CD (Compact Disc), and TTC (Toronto Transit Commission).

2.8 Coinage

Coinage is another word formation process which produces new words from scratch. Coinings or new words are often applied to new inventions or concepts that do not already exist in a language. Coinage is responsible for product names, company names, and so on. Words like Kleenex, Kodak, and Teflon are examples of product names created without using any of the previously mentioned word formation processes.

2.9 Eponymy

Eponyms are new words created from names of people. Typically, eponyms are new words whose meanings are associated with the individuals they were named after. For instance, Morse code was a communication system invented by Samuel Morse for telegraphs. Other examples of eponyms include the Ferris wheel, named after George Washington Gale Ferris Jr., jacuzzi named after Candido Jacuzzi, and watt named after a scientist James Watt.

While many eponyms are unambiguously related to names, some words are less obvious: for example, saxophone was named after Antoine Joseph Sax, a Belgian instrument maker who created it. Leotards, a one-piece garment worn by dancers, was named after Jules Leotard who was a French trapeze artist.

3. Inflectional Processes

3.1. Internal Change

Internal change is a process related to inflection. During internal change, one non-morphemic element is substituted for another to mark grammatical changes. For example, the English pairs goose – geese and foot – feet display an internal change in vowels. This change signals a singular – plural distinction in some irregular words.

Ablaut is a form of internal change that deals specifically with vowel alternations that mark grammatical contrasts. In this case, the vowel of the verb is replaced by another vowel to express some grammatical information. For instance, as seen in swim (present) - swam (past) and drink (present) - drank (past), the vowel of the verb changes to show it is past tense. As we saw above, the example of goose (singular) – geese (plural) is another case of ablaut in English.

3.2. Suppletion

Suppletion is the process by which one morpheme is replaced by another phonologically unrelated morpheme. In English, some verb forms are completely unrelated to their infinitival forms: go – went and be – was – is - am. Suppletion occurs in verbs and adjectives, as seen in the superlative forms of good and bad:

a. good – better – best

b. bad – worse – worst

In most cases of suppletion, irregularities in verb and adjective forms come from various historical developments that are no longer apparent to English speakers. Nonetheless, the current forms of the above examples have little to no phonological resemblance!