CHAPTER 11: LIQUIDS AND INTERMOLECULAR FORCES

A Molecular Comparison of Gases, Liquids, and Solids

CHARACTERISTICS PROPERTIES OF THE STATE OF MATTER

GAS | LIQUID | SOLID |

|---|---|---|

Assumes both volume and shape of its container | Assumes shape of portion of container it occupies | Retains own shape and volume |

Expands to fill its container | Does not expand to fill its container | Does not expand to fill its container |

Is compressible | Is virtually incompressible | Is virtually incompressible |

Flows readily | Flows readily | Does not flow |

Diffusion within a gas occurs rapidly | Diffusion within a liquid occurs slowly | Diffusion within a solid occurs extremely slowly |

Intermolecular Forces

The strengths of intermolecular forces vary over a wide range but are generally much weaker than intramolecular forces—ionic, metallic, or covalent bonds

Many properties of liquids, including boiling points, reflect the strength of the intermolecular forces.

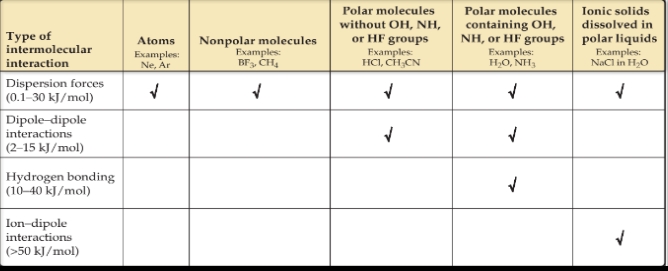

There are three types of intermolecular attractions that exist between electrically neutral molecules:

Dispersion Forces

Dipole-dipole attractions

Hydrogen bonding

The first two are collectively called van der Waals forces after Johannes van der Waals (1837–1923), who developed the equation for predicting the deviation of gases from ideal behavior.

Dispersion Forces

Fritz London, a German-American physicist, first proposed the origin of this attraction in 1930. London recognized that the motion of electrons in an atom or molecule can create an instantaneous, or momentary, dipole moment.

The Dispersion force

(also called London dispersion forces or induced dipole–induced dipole interactions).

The instantaneous dipole on one atom can induce an instantaneous dipole on an adjacent atom, causing the atoms to be attracted to each other.

It is significant only when molecules are very close together.

The ease with which the charge distribution is distorted is called the molecule’s polarizability.

Polarizability increases as the number of electrons in an atom or molecule increases.

Linear molecule—Larger surface area enhances intermolecular contact and increases dispersion force.

Spherical molecule—Smaller surface area diminishes intermolecular contact and decreases dispersion force.

Dipole–Dipole Interactions

These interactions originate from electrostatic attractions between the partially positive end of one molecule and the partially negative end of a neighboring molecule.

Hydrogen Bonding

A hydrogen bond is an attraction between a hydrogen atom attached to a highly electronegative atom (usually F, O, or N) and a nearby small electronegative atom in another molecule or chemical group.

Hydrogen bonds can be considered a special type of dipole–dipole attraction.

Ion–Dipole Forces

An ion–dipole force exists between an ion and a polar molecule. Cations are attracted to the negative end of a dipole, and anions are attracted to the positive end.

Comparing Intermolecular Forces

When comparing the relative strengths of intermolecular attractions, consider these generalizations:

When the molecules of two substances have comparable molecular weights and shapes, dispersion forces are approximately equal in the two substances.

When the molecules of two substances differ widely in molecular weights, and there is no hydrogen bonding, dispersion forces tend to determine which substance has the stronger intermolecular attractions.

Select Properties of Liquids

Viscosity

The resistance of a liquid to flow is called viscosity.

Can be measured by timing how long it takes a certain amount of the liquid to flow through a thin vertical tube.

Can also be determined by measuring the rate at which steel balls fall through the liquid.

Surface tension

Is the energy required to increase the surface area of a liquid by a unit amount.

Capillary Action

The rise of liquids up very narrow tubes.

Intermolecular forces that bind similar molecules to one another, such as the hydrogen bonding in water, are called cohesive forces.

Intermolecular forces that bind a substance to a surface are called adhesive forces.

Phase Changes when matter changes from one state (solid, liquid, gas, plasma) to another.

Energy Changes Accompany Phase Changes

Melting is called (somewhat confusingly) fusion. The increased freedom of motion of the particles requires energy, measured by the heat of fusion or enthalpy of fusion.

Vapor pressure

gas-phase particles exert a pressure.

Heat of vaporization

Or the enthalpy of vaporization.

The energy required to cause the transition of a given quantity of the liquid to the vapor.

Heat of sublimation

The particles of a solid can move directly into the gaseous state. The enthalpy change required for this transition.

Heating curve

A graph of temperature versus amount of heat added.

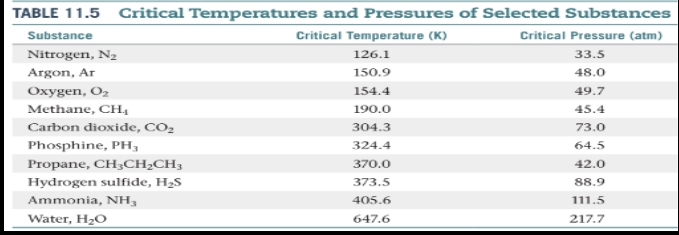

Critical temperature

The highest temperature at which a distinct liquid phase can form.

Critical pressure

is the pressure required to bring about liquefaction at this critical temperature.

Supercritical fluid

When the temperature exceeds the critical temperature and the pressure exceeds the critical pressure, the liquid and gas phases are indistinguishable from each other, and the substance is in a state.

Using supercritical fluid extraction, the components of mixtures can be separated from one another.

Vapor pressure

The pressure of the vapor attains a constant value.

Dynamic equilibrium

The condition in which two opposing processes occur simultaneously at equal rates.

Volatile

Liquids that evaporate readily.

Boiling point

Is the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the external pressure, acting on the liquid surface.

Normal boiling point

The boiling point of a liquid at 1 atm (760 torr) pressure.

A phase diagram is a graphic way to summarize the conditions under which equilibria exist between the different states of matter.

The phase diagram for any substance that can exist in all three phases of matter.

Generic phase diagram for a pure substance. The green line is the sublimation curve, the blue line is the melting curve, and the red line is the vapor-pressure curve.

The red curve is the vapor-pressure curve of the liquid, representing equilibrium between the liquid and gas phases.

The green curve, the sublimation curve, separates the solid phase from the gas phase and represents the change in the vapor pressure of the solid as it sublimes at different temperatures.

The blue curve, the melting curve, separates the solid phase from the liquid phase and represents the change in melting point of the solid with increasing pressure.

Point T, where the three curves intersect, is the triple point, and here all three phases are in equilibrium.

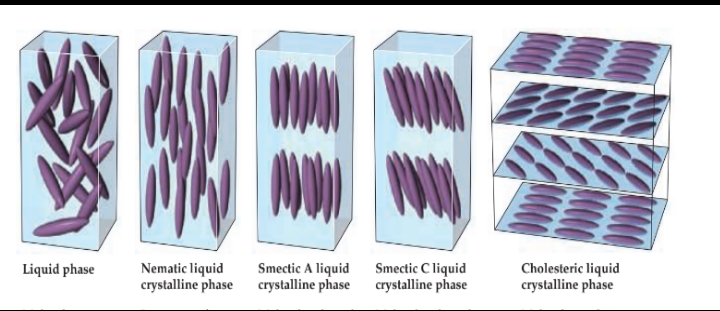

In 1888 Friedrich Reinitzer, an Austrian botanist, discovered that the organic compound cholesteryl benzoate has an interesting and unusual property.

Liquid Crystal

The term we use today for the viscous, milky state that some substances exhibit between the liquid and solid states.

Reinitzer’s work represents the first systematic report.

Types of Liquid Crystals

Liquid phase

Molecules arranged randomly.

Nematic liquid crystalline phase

Long axes of molecules aligned, but ends are not aligned.

Smectic A liquid crystalline phase

Molecules aligned in layers, long axes of molecules perpendicular to layer planes.

Smectic C liquid crystalline phase

Molecules aligned in layers, long axes of molecules inclined with respect to layer planes.

Cholesteric liquid crystalline phase

Molecules pack into layers, long axes of molecules in one layer rotated relative to the long axes in the layer above it.

Knowt

Knowt