Week 2: Neurological Disorders in the Pediatric Patient

Learning Outcomes

Differentiate between viral and bacterial meningitis.

Discuss the risk factors associated with bacterial meningitis.

Apply the appropriate nursing care for the patient with a neurological disorder.

Understand the complications associated with meningitis.

Explain Reye Syndrome.

Define seizures.

Identify seizure precautions.

Describe nursing interventions for the child having a seizure.

Meningitis: Overview and Key Concepts

Types

Viral (aseptic):

Supportive care

Causative agents include CMV, HSV, Enterovirus, HIV, and Arbovirus.

Bacterial (septic):

Contagious

Prognosis depends on how quickly care is initiated

Causative agents include Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal), Haemophilus influenzae type B ( Hib/this vaccine that’s given early can help prevent this ), E. coli.

Worse type due to how contagious it is and the chances of it leading to sepsis.

Neck pain (nuchal rigidity), pallor, and fever.

You know if an infant has neck pain when moving or won’t move their head at all

Fever is a big deal, as infants under 2 months are more likely to become septic.

Transmission and risk factors

Bacterial meningitis: injuries exposing CSF, crowded living conditions.

Use droplet precautions for these clients.

Laboratory findings by type

Bacterial: cloudy CSF, elevated WBC, elevated protein, decreased glucose, positive Gram stain.

Viral: clear CSF, normal to slightly elevated WBC, normal to slightly elevated protein, normal glucose, negative Gram stain.

Cultures to order would be a spinal tap/lumbar puncture or a blood test/culture (which can be done by the nurse) to rule out.

Blood test would take about 48-72 hours for results.

Blood culture should be prioritized (must be important)!!

CBC will also be done to check the white blood cell count.

BMP is used to see the BUN, creatinine, and electrolytes.

The child should be on IV to prevent dehydration from all the draws needed for labs.

Get the bug before giving the drug!

Gold standard diagnostics and imaging

Lumbar puncture (LP) is essential to identify etiologies and CSF abnormalities; CT/MRI may be used to identify increased ICP or abscess before LP in certain cases.

LP is avoided if increased ICP is suspected to prevent brain herniation.

Clinical Presentation by Age (Expected Findings)

Neonates & Infants

Bulging fontanelles, increased head circumference, high-pitched/neuro cry, irritability, temperature instability, poor feeding, poor suck, vomiting/diarrhea, seizures, nuchal rigidity (late infancy).

Osmotic diuretic (manotolol) is used to help decrease intracranial pressure

Elevate the head of the bed at least 30% to help relieve the pressure

Brain rest (dim the lights, anagelsics, etc.)

Use the same for a headache and a concussion!

Children

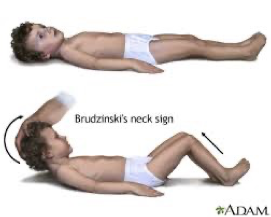

Headache, seizures, nuchal rigidity, photophobia, decreased LOC, vomiting, sensory alterations, positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, irritability/delirium/coma, hyperactivity with variable reflex response, chills, and fever.

Signs and Diagnostic/Clinical Markers

Petechiae and purpura indicate meningococcemia risk (warning signs for meningococcal disease).

Brudzinski’s neck sign and Kernig’s sign are classic meningitis indicators.

Early vs. late signs (e.g., rash progression, pale skin, cyanosis around lips).

“ADAM” is noted as a mnemonic in the slides (context unclear in excerpt).

Diagnostic Procedures and Precautions

Diagnostics

LP: identifies CSF characteristics; view for increased ICP.

CT/MRI: assess structural abnormalities (an abscess) and ICP.

Definitive diagnosis requires identification of the infectious agent; LP often precedes antibiotics if safe.

Isolation and precautions

Droplet precautions until antibiotics are initiated and infection control clearance achieved.

Monitoring and supportive care

Monitor vital signs, urine output, pain, neuro status, and fluid status.

Fontanels/head circumference assessment: A bulging fontanel indicates possible ICP.

Fluid management: correct fluids first, then restrict fluids to keep sodium within normal limits; NPO status if decreased LOC, advance as LOC improves.

NPO will not be fed until you get an order that they can eat due to aspiration risk.

Comfort measures and environmental control: reduce stimuli; safety/seizure precautions.

Seizure precautions (should be at the bedside for these patients)

Safety and suction

Bag and mask

Padding

Keep rails up

Oxygenation

Treatments and Nursing Care for Meningitis

Medications

Antibiotics (as indicated by bacterial etiology); corticosteroids are not indicated for viral meningitis.

Analgesics, IV fluids, antiepileptics as needed.

Steroids are given for bacterial meningitis to reduce inflammation and prevent complications, while ensuring careful monitoring of the patient's response to treatment.

Vaccination and prevention education

HiB vaccine; Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) reduces the risk of bacterial meningitis.

Hib and PCV as key immunizations; isolation procedures explained to families.

Case-management and education notes

Case Study A (4-year-old with fever and stiff neck): questions guide diagnosis, presenting symptoms, causes, diagnostics, and treatment.

Reye Syndrome considerations: if influenza or viral illness co-occurs, avoid aspirin in children with viral illnesses.

Reye Syndrome: Overview and Nursing Considerations

Definition and significance

Life-threatening disorder; primarily affects the liver and brain → liver dysfunction and cerebral edema.

Caused by viral infections, particularly influenza or varicella, in children who are treated with aspirin.

Peak incidence when influenza is common; prognosis is best with early recognition and treatment.

Pathophysiology and presentation

Cerebral edema, fatty liver, clotting abnormalities, confusion, profuse vomiting, seizures, loss of consciousness, personality changes (delirium, combativeness), lethargy, irritability, coma.

The worst that can happen for this client is ending in a coma, going into liver failure, loss of consciousness, permanent neurological deficits, and status epilepticus.

Diagnostic tests

Liver enzymes (ALT & AST), blood ammonia level, electrolytes, and extended coagulation times; diagnostics may include liver biopsy and CSF analysis to rule out meningitis.

Liver biopsy will lead to the client being on bed rest.

Treatments and supportive care

Osmotic diuretic (Mannitol) to reduce cerebral edema; Vitamin K (helps with clotting); oxygen and respiratory support; rehabilitation therapies (OT, PT, nutrition, speech therapy).

Nursing interventions

Maintain hydration; monitor VS (frequent neuro checks every 2-3 hours), LOC, oxygenation; positioning to optimize cerebral perfusion; monitor coagulation and prevent hemorrhage; pain management; prepare for airway management and possible intubation; seizure and bleeding precautions; provide education and reassurance to family.

Avoid Pepto-Bismol for kids.

Seizures in the Pediatric Client

Definition and general concepts

A seizure is a physical finding or change in behavior that occurs after episodes of abnormal electrical activity in the brain.

Mnemonic for causes: VITMAIN (Vascular, Infections, Trauma, AV malformation, Metabolic, Idiopathic, Neoplasms, Others like fever, sleep deprivation, drugs, etc.).

Types of epilepsy (overview)

Generalized and focal seizures are described with subtypes below.

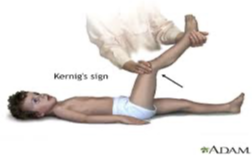

Generalized seizures: Tonic-Clonic

Tonic phase: about 10-20 seconds

This is the tone of the seizure

Clonic phase: about 30-50 seconds

This is the movement/jerking of the seizure

Postictal state: about 30 minutes

Secretions may come out of their mouth during this phase, and it is important to monitor for airway obstruction.

Nursing care when a seizure begins: Help the child safely lie on the ground and ensure they are on their side to minimize the risk of choking on any secretions.

Freak out if the seizure continues past 5 minutes (due to status epilepticus)

If past 5 minutes, you must administer AEDs and medically intervene.

Seizure precautions:

Suction: clear the airway to prevent aspiration, ensuring that any vomit or secretions are promptly removed.

Oxygenation: Ensure the patient receives an adequate oxygen supply, monitoring pulse oximetry levels to avoid hypoxia during seizure activity.

Bag and mask: Use a bag-valve mask to provide assisted ventilation if the patient becomes apneic or has inadequate spontaneous breathing.

Seizure pads: Place seizure pads around the patient to prevent injury during a seizure and provide a safe environment until the seizure subsides.

Tonic-clonic seizures are out of your control and require immediate intervention to ensure the patient's safety and stabilization.

Absence seizures

Onset: 4-12 years, LOC (loss of consciousness) lasts 5-10 seconds; lucid interval resumes immediately; characteristically a blank stare with automatisms and brief confusion.

Myoclonic seizures

Brief contractions may be symmetric or asymmetric; no guaranteed postictal state; they may involve the face, trunk, or limbs, but might not LOC.

Atonic (akinetic) seizures

Occur at 2-5 years; loss of muscle tone for a few seconds; followed by a period of confusion; often with “drop attacks.”

Assure the client has a helmet on when hospitalized to prevent brain injury when falling.

Infantile spasms

Peak at 3-7 months; sudden, brief contractions with flexed head and extended arms; possible nystagmus or eye deviation; may have LOC; treatment includes ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone).

This hormone can help treat and prevent seizures.

It can lead to brain deficits and long-term developmental issues if not treated promptly.

Febrile seizures

Associated with a sudden spike in temperature (e.g., 38.9–40.0°C or 102–104°F); typically 15–20 seconds; management includes acetaminophen or ibuprofen, tepid baths, and light clothing.

Accompanying respiratory infections.

High chances that this is genetic.

Diagnostics for seizures

EEG (electroencephalogram):

Records brain activity

Can be performed during sleep, wakefulness, stimulation, or hyperventilation

May last from 1 hour to extended monitoring

A normal EEG does not rule out seizures.

MRI and CT scans; LP if indicated.

MRI looks at brain function.

Lumbar Puncture makes sure the seizure isn’t caused by an infection.

Questioning if they are leading to a septic episode.

Nursing care during a seizure (Patient-Centered Care)

Protect from injury; maintain airway; position side-lying; do not restrain; loosen restrictive clothing; do not put anything in the mouth; prepare for oxygenation; remove glasses; time and document onset and characteristics; postictal assessment and monitoring; ensure safety and comfort; SZ precautions as ordered.

Post-seizure care and education

Side-lying position; check breathing and airway; monitor neuro status; allow rest and reorientation; document postictal duration; reinforce seizure precautions.

Therapeutic care and medications

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) to decrease incidence/severity

Nursing Actions: monitor therapeutic levels

Nursing Consideration: consider diazepam as needed

Interprofessional Care: involve the school nurse and nutrition

Therapeutic Procedures: consider brain surgery or vagal nerve stimulator in certain cases (that are extreme).

AEDs are administered if the length of the seizure exceeds 5 minutes.

PRN order should be placed, and family should be educated on how to rectally administer it at home.

Ketogenic diet

For children <8 years with myoclonic or absence seizures, high-fat, low-carbohydrate, low-protein diets; ketosis slows electrical impulses.

Client Education: If administering Depakote Sprinkle, mix it in apple sauce or ice cream (cannot be mixed in liquids, only solids).

Complications

Status epilepticus: prolonged or continuous seizures; requires urgent attention.

Potential developmental delays require referrals and support.

Acute management and emergency indicators

Call EMS for first seizure, seizure >5 minutes, apnea, status epilepticus, unequal pupils after a seizure, continuous vomiting for 30 min after seizure, unresponsive to pain, seizure in water.

EEG education and prep tips

Avoid caffeine before EEG; wash hair before procedure; do not withhold food; avoid analgesics before EEG as they can alter results.

Seizure risk factors and education for families

Febrile episodes, hypoglycemia, sodium imbalances; high lead levels associated with seizures; diphtheria is not a seizure risk factor.

Treatment options when seizures worsen or are resistant

Vagal nerve stimulator; additional AEDs; corpus callosotomy; focal resection; avoid radiation therapy (used primarily for cancer).

Head Injuries: Concussions and Skull Fractures

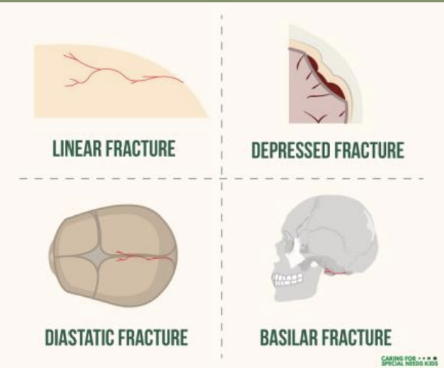

Skull fracture types

Linear, depressed, comminuted, basilar, open, growing fractures.

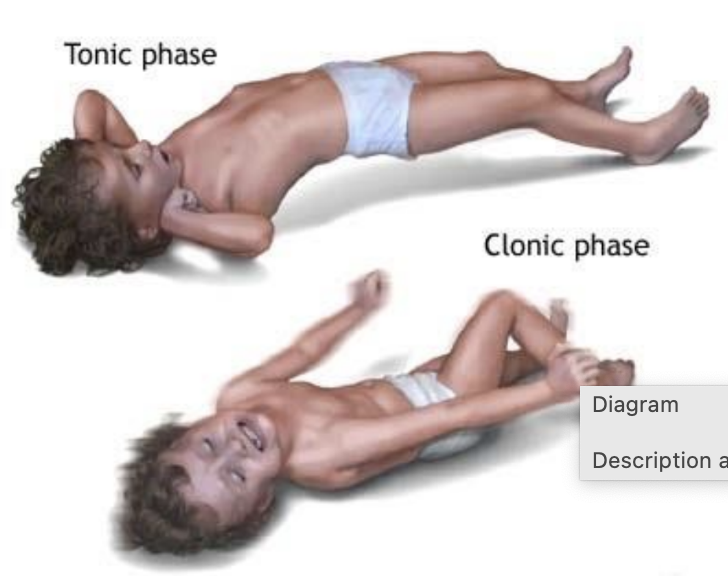

Concussions

Result from rotational forces: shear, twisting; coup-contrecoup injuries.

At risk for fractures, swelling,

Photosensitivity, headaches, sensitive to loud sounds, nausea, and vomiting (if done twice, this is a sign)!

This is because it could be a sign of a brain bleed (order a CT to ensure this).

Off from physical activity for 2-4 weeks due to the possibility of second-impact syndrome.

Graded I-III; symptoms include headache, nausea, amnesia, and potential confusion.

Immediate management: ABCs; cervical stabilization; symptoms may be delayed; athletes may underreport.

Concussion prevention and complications

Second-Impact Syndrome risk after a second head impact when not fully recovered; it can be fatal.

Type of Skull Fractures

Linear, depressed, comminuted, basilar, open, and growing fractures.

Comminuted fractures are alarming as they are repetitive linear fractures (seen in situations of abuse).

Basilar skull fracture signs

Leakage of CSF from nose or ears, raccoon eyes, battle sign; treat with antibiotics.

Ecchymosis around the nose and ears.

Health promotion and safety

Wear helmets, use seat belts, avoid dangerous activities, never shake a baby, proper car seat.

Mannitol, a diuretic used for injury.

Head injury assessment and nursing care*

Stabilize spine if needed; monitor VS, LOC, ICP; maintain ABCs; padded restraints if needed; monitor for CSF leakage; reduce ICP and prevent immobility complications; promote cerebral perfusion with fluids; maintain safety; provide nutrition and communication.

Clinical scenarios and priorities

After a motor vehicle accident, an unresponsive child with a bleeding forehead laceration: priority is cervical spine stabilization; other interventions follow.

ICP indicators and management in adolescents

Headache, changes in pupillary response, altered motor response, increased sleep, altered sensory response; maintain a quiet environment

Avoid neck flexion and Valsalva maneuvers; proper head elevation and positioning to avoid ICP elevation.

Management specifics for ICP

Avoid routine ET suctioning (risk of brain injury through skull fracture); maintain head alignment; avoid neck flexion; avoid abdominal pressure; keep patient in a neutral position; limit stimuli.

Practical Implications

Early recognition of meningitis and Reye syndrome is critical to prevent rapid deterioration in pediatric patients.

Vaccination programs (HiB, PCV) have a clear public health impact by reducing incidence of bacterial meningitis, reflecting ethical commitments to community health and equity.

Management of seizures includes respect for patient autonomy and family education, while prioritizing safety during acute events.

Concussion management in youth sports emphasizes patient safety, return-to-play decisions, and long-term neurological health.

The care of head-injured children requires balancing aggressive protection of the CNS with minimizing invasive procedures, highlighting the principle of non-maleficence in pediatrics.