Chapter 6: Grammar Review

Complements

Resultative Complements

- In Chinese, a verb can be followed by an adjective or another verb to indicate the result of an action. The adjective or the second verb is called a resultative complement.

- 我吃饱了。

- 不管我的同屋喜不喜欢我,我都不会搬出去。

- Some verbs can only take certain other verbs or adjectives as their resultative complements.

- Students should remember that each verb and its resultative complements must be viewed as one word.

- Also note that only verbs and adjectives, because they are able to convey a sense of result, can serve as resultative complements.

- Such verbs include: “会”,“完”,“⻅”,“懂”,“开”,“住”,“给”,“倒”,“掉”,“死”,etc.

- Such adjectives include: “ 对 ” ,“ 错 ”, “ 好 ” , “坏”,“早”,“晚”,“清楚”, etc.

- Again, a resultative complement indicates the result or completion of an action.

- 今天的作业⼀定要做完。

- 我的学⽣证丢了,我找了半天也没找到。

- A resultative complement can also clarify an %%action or a state%%.

- 你们都听懂了吗?

- 他吃了三个汉堡包还没吃饱。

- Some resultative complements that appear after adjectives or verbs denote %%psychological state of an extreme degree%%.

- 她的笔记本电脑丢了,她快急死了。

- 他考上了哈佛, 他⽗⺟可乐坏了。

Directional Complements (Indicating Direction)

- The simplest directional complements are formed from direction verbs and either “来” or “去” to indicate motion toward or away from the speaker.

- There are six basic direction verbs: “上”, “下”, “进”, “出”, “回”, “过”.

- When combined with “来” and “去”,they yield twelve different complements: “上来”, “上去”, “下来”, “下去”, “进来”, “进去”, “出来”, “出去”, “回来”, “回去”, “过来”, “过去”.

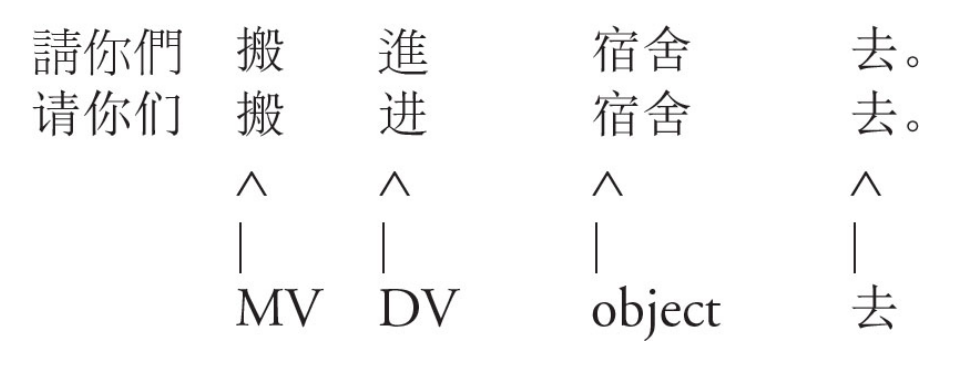

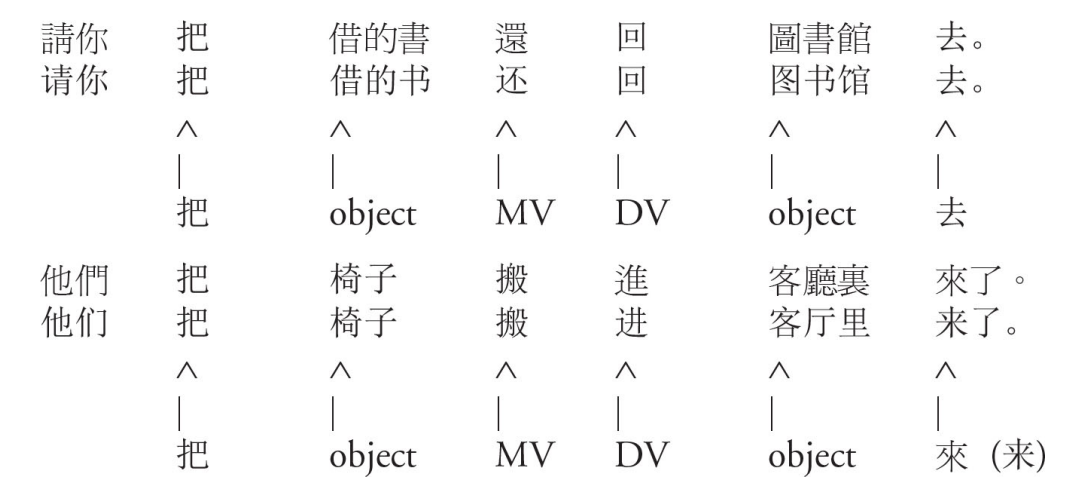

- These twelve directional complements can serve as compound directional complements when attached to other verbs, such as “⾛进来”, “站 过去”, “坐下来”, etc.

- The main verb expresses the action, while the complement describes the direction in which the action is carried out.

- Any action verb that involves directional movement may become a compound directional complement.

| main verb | directional complement |

|---|---|

| ⾛ | 进来 |

| 站 | 过去 |

| 坐 | 下来 |

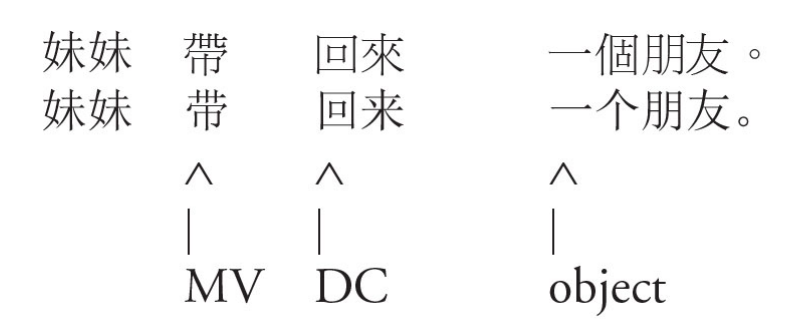

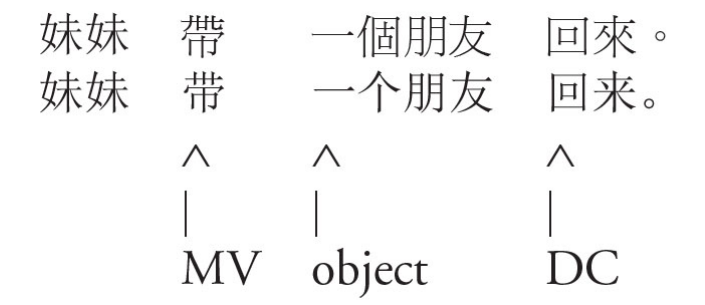

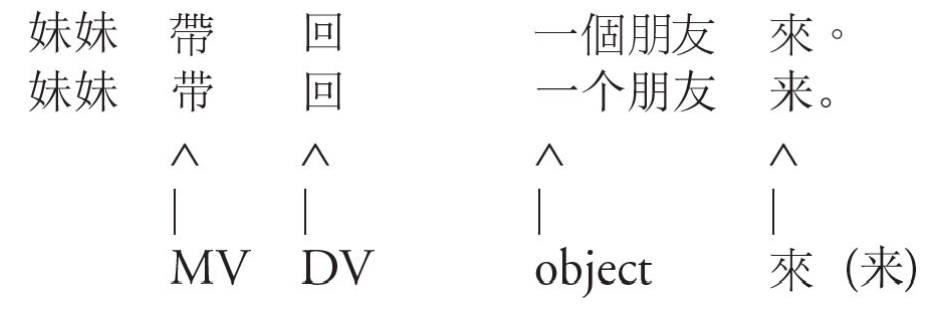

If the Directional Complement is followed by an object, the object (noun) can be placed either before or after the Main Verb, or it can be inserted between the main verb and the Direction Verb.

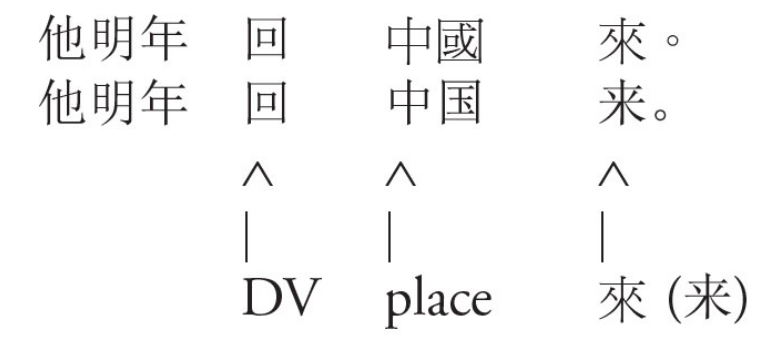

If the object signifies a place, it is usually inserted after the direction verb, or between the main verb and the direction verb.

Directional complements can also be used with a 把-sentence.

Directional Complements (Indicating State)

- When the directional complement “起来” is used with a verb, it indicates that another action is starting. It can also indicate a change from one action to another.

- ⽗⺟⼀吵架,孩⼦就哭起来了。

- 两个⽼朋友⼀坐下就聊起天⼉来。

- 他⼀看起电视来把什么都忘了。

- 你快把那些书收起来吧。

- When used with an adjective, “起來” can indicate a change in quality or state, such as speed, light, temperature, or weight.

- ⽔所以深起来是因为下⼤⾬了。

- 美国汽油的价格从上个⽉⾼起来了。

- 这两年学中⽂的⼈⼀下⼦多起来了。

- When the directional complement ““ 下 来 ” is used with an adjective, it indicates the decrease of a quality to a lesser state, such as a gradual change from bright to dark, strong to weak, or motion to stillness.

- 天慢慢地⿊下來了。

- 只要妈妈⽣⽓,她的声⾳就会低下来。

- 灯关了,房间⾥⿊了下来。

- When “下來” (“下来”) is used with a verb, it indicates that something has become settled or fixed as the result of an action.

- ⽗⺟叫他快点⼉把专业定下来。

- 想在纽约住下来。

- ⽼师讲的语法你都记下来了吗?

- The directional complement “下去” indicates the continuation of a state or an action. When “下去” is used with an adjective, it may indicate not just the continuation of a state but its intensification as well.

- 说下去!

- 这部电影我看不下去了。

- 看起来天⽓会冷下去。

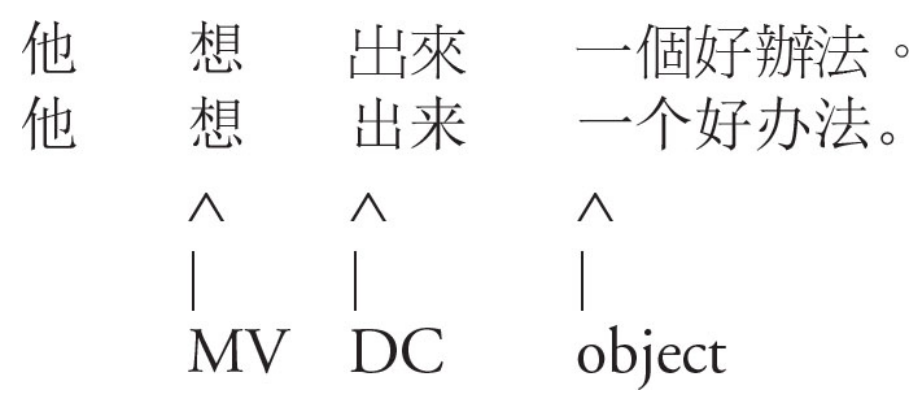

Directional Complements (Indicating Result)

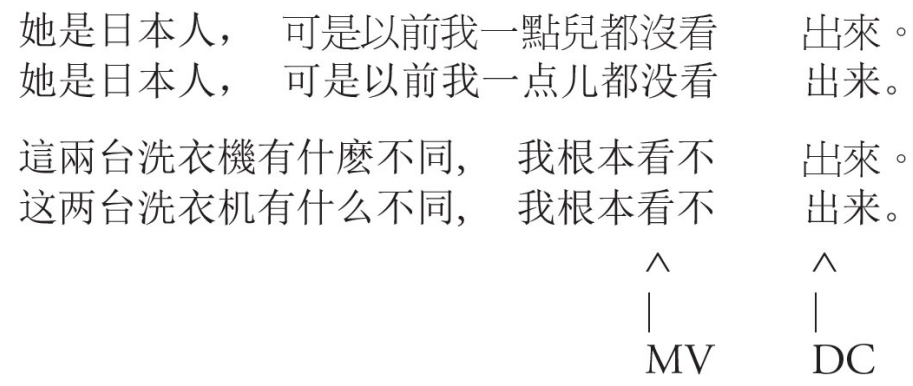

A directional complement used with “V + 出来” signifies a change in status. When there is an object, one can often leave out the word “来”.

This can be rewritten as:

When the directional complement occurs at the end of a sentence, however, one must use the full complement.

A directional complement with “V + 起来” means “seem.”

- 这台电视机看起来是⽇本⽣产的。

- 这⾸歌听起来不是她唱的。

- 这个菜吃起来肯定不是你做的,是你妈妈做的吧?

Complements of State

- A complement of state is usually %%placed after a verb or an adjective%%, with the structural particle “得.” It expresses a degree, an evaluation, a judgment, or a description related to a verb, an adjective, or a noun preceding “得.”

- ⾼兴得跳起来。

- 我的功课多得很。

- In a negative form, the word “不” or “没有” is placed after a verb or an adjective, preceding the complement.

- 天⽓热得我吃不下饭。

- To use a complement of state in a sentence with a direct object, the verb is repeated.

- 我今天考试考得不太理想。

- If the verb is not repeated, the object must be placed before the subject or the verb.

- 这部电影看得我快睡着了。

Potential Complements

Potential complements are formed by inserting “得” or “不” between a verb and a resultative complement.

- 今天的作业你半个⼩时做得完吗?

Or, they may appear between a verb and a directional complement to indicate whether a certain result will be realized or not.

- 开⻋太难了,我学不下去了。

The complements can be constructed as the equivalent of “能” and “不能.” Consider using “能” to rewrite the above example “今天的作业你半个⼩时做得完吗?”:

- 今天的作业你半个⼩时能做完吗?

Potential complements appear primarily in negative sentences, or in questions. The affirmative form of the resultative complement and the negative form of a potential complement can be put together to form a question.

- Q: 那本中⽂字典你 买得到 买不到?

- A: 买得到。

Potential complements have a unique function that cannot be fulfilled by the “不能 + verb + complement” construction. A potential complement cannot be used in a “把”—sentence, either. The following sentences are incorrect.

- ⽼师说得太快了,我不能听清楚。

- 你⻋太⼩了,我们五个⼈不能都坐下。

- 我家没有多少钱,我不能上那么贵的⼤学。

- 我把今天的功课做不完。

The following sentences are correct.

- ⽼师说得太快了,我听不清楚。

- 你⻋太⼩了,我们五个⼈坐不下。

- 我家没有多少钱,我上不了那么贵的⼤学。

- 我今天的功课做不完。

Sentences With Special Predicates

The “是”—Sentences

Sentences with “是” as the predicate are known as “是”—sentences. The negative form of a“是”—sentence is formed by adding the negative adverb “不” before “是.”

The subject of the “是”—sentence may be

- a noun:

- 华盛顿市是美国的⾸都。

- a pronoun:

- 我是⾼中⼆年级的学⽣。

- a verb:

- 休息也是⼀种⼯作。

- an adjective:

- 热情是她最⼤的特点。

- a numeral–measure word phrase:

- ⼆⼗⼀点就是晚上九点。

- a verb-object phrase:

- 学中⽂是⼀项艰巨的任务。

- a complementary phrase:

- 努⼒⼯作是成功的条件。

- or a 的-phrase:

- 穿⿊⾊⾐服的不是我们的历史⽼师,穿⽩⾐服的是。

The object following the predicate verb “是” may include

- a noun:

- 我爸爸是医⽣,妈妈是⽼师。

- a pronoun:

- 把这件事告诉⽼师的⼈是她,不是我。

- a verb phrase:

- 做家庭妇⼥也是⼯作。

- an adjective:

- 那个⽼师的特点是严格。

- a numeral-measure word phrase:

- 今天最⾼⽓温是98度。

- a 的-phrase:

- 那个帅哥是个打篮球的。

- a verb-object phrase:

- 爸爸最不喜欢的事情是逛商店。

- a complementary phrase:

- 你今天的任务就是休息好。

- a subject-predicate phrase:

- 这次作业的安排是⼤家在课堂上⼀起做。

Note that the verb “是” remains unchanged in this form in all situations. It can signify any time, place, person, or thing, and requires no conjugation for tense or gender.

The Passive Voice

- A sentence whose subject is the receiver of an action is called a passive sentence.

Sentences with the Passive Marker “被”

Pattern: Subject +被+ object + verb + other element

我的书被邮局寄丢了。

那个⼩男孩被他爸爸骂了⼀顿。

我家的猫被⼀只⽼⿏咬伤了。

Note that in a sentence with the passive marker “被,” the “doer” may be implicit.

- 他被叫到⽼师的办公室去了。

- 座位全都被坐了。

- 那种名牌⽜仔裤被买光了。

A sentence with the passive marker “被” sometimes refers to unpleasant or undesired situations.

- 他被⼥朋友甩了。

- 我被罚款了。

An adverb must be placed before the word “被.”

- 他总是被批评。

- 那个⼥孩⼦很乖,常常被⼤⼈夸奖。

The passive markers can also be “叫,” “让”, or “给”.

- 洗⾐机让⼈修好了。

- 我的⻋叫谁开⾛了?

- 酒都给他喝完了。

Unmarked Passive Sentences

- Some sentences have no special marker words to indicate the passive voice but nevertheless are notionally passive (passive in meaning).

- ⽔果吃完了,应该去买了。

- 房⼦租好了,明天搬家吧。

- 護照帶了嗎?护照带了吗?

- 这次作业做得不错。

The “把” Sentence

- The “把” sentence is used with actions that change the state of a definite object.

- ⽼师把我的作业丢了。

- 请后边的同学把窗⼾关上。

- There must be another element following the verb, such as:

- a complement of result:

- 她把⾐服洗了。

- a complement of manner:

- 她把⾐服洗得很⼲净。

- a directional complement:

- 她把⾐服拿回来了。

- an aspect particle “了”:

- 她把⾐服丟了。

- The object in a 把—sentence is usually definite. The speaker is referring to a particular item or items in the real world, which are presumably known to both the speaker and addressee.

- 你把那扇门打开。

- 外⾯下⾬呢,你把我的⾬伞带上吧。

- The main verb in a “把”—sentence must be an action verb, such as “打”, “穿”, “拉”, “准备”, “布置”, etc.

- 今天外⾯很冷,出门的时候把那件⼤⾐穿上。

- 太危险了,快把孩⼦拉回来。

- 请⼤家把笔和纸准备好,我们开始听写。

- Note that in a “把”—sentence, negative adverbs and modal verbs can be placed before “把.”

- 你不把中⽂功课做完就不能去看电影。

- 我想把男朋友送给我的新⾐服穿上。

- Note also, if the object is too long (e.g., contains one or more modifiers), using the “把” pattern may result in a smoother, more natural phrasing than if the long object were to follow the verb.

- 妹妹把去年我⽗⺟从中国给她买的中⽂书借给同学了。

- 他把在⾼中校园⾥听到的那个可怕的消息告诉了我。

Existential Sentences

- Existential sentences indicate the %%existence of some thing(s) at some location(s)%%, such as, “There is some thing at some location,” in English. The word order of an existential sentence is rather different from that of other Chinese sentences.

Existential Sentences with “有”

- Pattern: Place word + location + 有 + (numerals + measure word) + noun

- 教室的旁边有⼀个图书馆。

- 墙上有⼀些中⽂字。

Existential Sentences with “是”

- Pattern: Place word + location + 是 + (numerals + measure word) + noun

- 床上是⼀条毯⼦。

- ⼤学校园的旁边是⼀条⾼速公路。

Existential Sentences with “着”

- This pattern describes where an object is specifically located. Only verbs that leave an object in an ongoing state can be used in this pattern.

- For inanimate objects, the verbs that can be used in this pattern include: “放”, “挂”, “贴”, “摆”, “停”, “写”, etc.

- Pattern: Place word + verb-“着” + (numerals + measure word) + object

- 桌⼦上放着⼀本字典。

- ⾐柜⾥挂着很多⾐服。

- 教室⾥坐着很多学⽣。

Existential Sentences in Describing People

- Pattern: Person + place on body + verb-“著” (“着”) + (numerals + measure word) + object

- 他头上戴着⼀顶帽⼦,⾝上穿著⼀件⽑⾐,脚上穿著⼀双⽪鞋。

- 姑娘脖⼦上戴着⼀条项链,⼿上戴着⼀块名牌⼿表,肩上却背着⼀ 个⾮常难看的包。

Existential Sentences in Expressing People’s Appearance or Disappearance

- Pattern: Place word/Time word + verbal phrase + (numerals + measure word) + noun

- 昨天我家来了⼀位客⼈。

- 那边跑来⼀个⼩男孩。

- 楼上⾛下来⼏个我不认识的⼈。

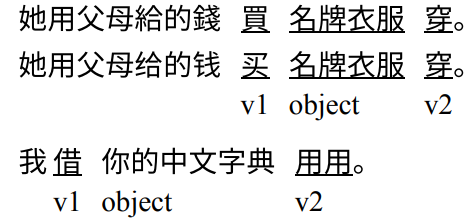

Sentences with Verbal Constructions in a Series

This kind of sentence has two or more verbs or verbal structures that are used as the predicate of the same subject.

- 我去图书馆借书。

The negative form is usually made by adding the negative adverb “不” or “沒有” before the first predicate verb.

- ⾼中学⽣没有时间打⼯。

- 他们不来我们学校⽐赛了。

If the sentence needs an adverbial adjunct, it is normally placed between the subject and the first predicate verb.

- 我得去图书馆借⼏本书。

- 我这学期有时间学中⽂。

Usually the second verb indicates the purpose of the first verb, or the first verb-object phrase explains the means for achieving the second.

- ⽼师要找我谈谈⼩考的事情。

- 我每天坐校⻋去学校。

When the second verb indicates the purpose of the first, both verbs typically share a common object; therefore, the second verb usually omits the object.

Pivotal Sentences

- A pivotal sentence has two predicates.

- Of the two predicates in the sentence, the object of the first predicate (verb) is at the same time the subject of the second one.

- This part is called the pivot, and sentences with verb predicates of this sort are identified as pivotal sentences.

- The basic pattern of pivotal sentences is: Subject + predicate (verb) + pivot + predicate of the pivot

- 妈妈说我懒死了。

- 房东催我交房租。

- 楼道⾥有⼈⼤喊⼤叫。

- ⽼师要求我们写⼀篇关于环境保护的作⽂。

- In the negative form of a pivotal sentence, the adverbs “不” or “沒有” are usually placed between the subject and the first predicate.

- ⽗⺟没有让他买那么贵的⻋。

- In general, verbs indicating a request or a command are used in first predicate; for example: “请”, “让”, “叫,” “使,” “命令,” “禁 ⽌,” etc. In this case, the pivotal predicate may either be a verbal predicate or an adjectival predicate.

- 我请他在台湾买本中⽂字典。

- 我⽗⺟⾮叫我读医科⼤学不可,他们不让我学⽂科

- ⽼師請學⽣家⻑們來⼀趟學校。

- ⽼师请学⽣家⻓们来⼀趟学校。

Comparison

Expressing Difference

- Pattern: A⽐B + (adverb) + adjective/verb + (numeral + measure word + noun)

- 我们班⽐你们班少两个学⽣。

- 你⽐他多学了⼀年中⽂。

- 我⽐他更喜欢看篮球⽐赛。

- The negative version of this structure can take one of the following forms:

- adding “不” or “沒有” before “⽐.”

- 我们学校不⽐你们学校有名。

- 今天沒有⽐昨天热。

- replacing “⽐” with “沒有” “不如.”

- 他们的⾼中没有我们的有名。

- 纽约的天⽓不如加州的好。

- Adverbs such as “很,” “⾮常,” “⼗分” “特別,” “真,” and “最” cannot be used in this type of sentence. Words such as “⼀点⼉”, “⼀些,” “得多,” and “多了” should be used instead.

- 哥哥⽐弟弟⾼⼀点⼉。

- 妹妹⽐姐姐漂亮得多。

- 我们班的⽼师⽐你们的⽼师年轻⼀些。

- If a verb has an object, the verb should be reduplicated.

- 我开⻋⽐她开得好多了。

- 你学中⽂⽐我学得认真得多。

- Modal verbs like “会” and “应该” can be placed before the action verb in this type of sentence.

- 弟弟⽐哥哥会打篮球。

- ⽼年⼈⽐年轻⼈更应该注意⾝体。

- The “A⽐B” structure can be used adverbially. In this case, it can be added between the subject and the adjective or verb.

- 我们这个星期⽐上个星期忙。

- 他在学校⽐在家⾥⾼兴多了。

Expressing Similarity

Pattern 1: A跟B + ⼀樣 (样)

A跟B + 不 + ⼀樣 (样)

- 我的⽜仔裤跟你的⽜仔裤⼀样。

- 东岸跟⻄岸完全不⼀样。

- 他跟别的中国⼈有点⼉不⼀样。

Pattern 2: A + 像+ B + (other element)

A + 不像+ B + (other element)

- 他⻓得很像他爸爸。

- 英语⽼师不像四⼗岁的⼈,像三⼗岁的。

- 今年夏天,纽约像洛杉矶那么热。

- 我不像你那么喜欢穿名牌的⾐服。

Pattern 3: A跟B + 差不多/相似

- 他买的⾐服跟你的相似。

- ⼩張⻑得跟⼩王差不多,所以我常看錯⼈。

Expressing Similarity with “有”

- Pattern: A有B + 那麽/這麽 (那么/这么) + adjective

- 我的房间有你的房间那么⼤。

- 他跑得有汽⻋那么快。

Expressing Emphasis

Using the “是…的” Construction

- To emphasize a past action or a past event, one should use the structure “是…的” to indicate the time, place, manner, or purpose of the occurrence or the agent of the action. “ 的 ,” which often follows the verb, may be placed either before or after the object.

- Patterns:

- Subject + 是 + time/place + verb + object + 的

- Subject + 是 + time/place + verb + 的 + object

- Examples:

- 你是⼏点吃早饭的?

- 你是⼏点吃的早饭?

- 你是在什么地⽅学的中⽂?

- 你是在什么地⽅学中⽂的?

Using Rhetorical Questions with “難道” (“难道”)

- A rhetorical question with “難道” (“难道”) is much more emphatic than a non-rhetorical question.

- 难道可以对⾃⼰的⾏为不负责任吗?

- 难道⽗⺟的话都对吗?

- 难道你不会写⾃⼰的中⽂名字吗?

- 难道今天没有考试吗?

Using Double Negative Sentences

- A double negative is often used in a sentence to indicate affirmation. Common patterns of emphasizing affirmation with double negatives are “不…不…,” “沒有…不…,” “不…沒有,” and “沒有不… .”

- 学⽣不应该不做功课。

- 我们这次考试没有⼈不及格。

- 爸爸不能没有⼯作。

- 哥哥没有不喜欢的体育运动。

Complex Sentences

- Complex sentences consist of two or more simple sentences called clauses. Complex sentences are used to express a complete thought and are spoken with a certain intonation.

- ⼩王刚⾛,⽼张来了。

- ⻛停了,⾬也不下了。

- 如果中⽂太难,我就不学了。

- 她的⾐服很漂亮,我的不好看。

- Two or more clauses in a complex sentence are separated by a pause when spoken, and indicated by a comma or a semicolon in writing. The sentence is spoken as one entity. If the clauses share a common subject, then the subject does not have to be repeated.

- ⻢克会英⽂,⻢克会⻄班⽛⽂,⻢克不会法⽂。

- 我想省钱,我不想买太贵的电脑。

- In a complex sentence, clauses have various relationships that are often denoted by conjunctions.

- 因为没有买到⽕⻋票, 所以他们得在旅馆住⼀天。

- |既然你觉得物理太难了,你今年就别选这门课了。

- Instead of conjunctions, some adverbs may also connect clauses. Conjunctions or adverbs can be placed either in the first or second clause, depending on the relationship between the clauses. Some conjunction words are used before the subject, and some are used after.

- 要是你们有时间,你们就看这部电影吧。

- 虽然今天没有作业,我也要好好复习复习。

- Clauses in a complex sentence may have various types of predicates.

- 今天星期⼀,明天星期⼆。 (sentence with predicate)

- ⽆论中⽂多么难,我都要学好。(sentence with adjectival predicate)

- 只要有决⼼,就有学好中⽂的希望。(sentence with verbal predicate)

- Complex sentences can be roughly divided into two groups: coordinate complex sentences and subordinate complex sentences. These two groups can be further divided into subclasses based on their clauses’ relationships.

Coordinate Complex Sentences

- Complex sentences indicating coordinate relations are called coordinate sentences. In a coordinate complex sentence, the clauses are equivalent in content and weight.

- 这位是李⼩姐,那位是张先⽣。

- 你喜欢吃中国饭还是法国饭?

- The clauses with the coordinative relationship explain or describe several things respectively or explain the different aspects of one thing.

- 他从台湾来的,我是从新加坡来的。

- 她⼀边⼯作,⼀边打⼯。

- The clauses with the successive relationship are arranged according to the sequence of actions or events. The meanings of the clauses are coherent..

- 他⼥朋友跟他⼀分⼿,他就离开美国了。

- 你们应该先做⼀个演讲,再写⼀篇读书报告。

- The clauses with the progressive relationship use the second clause to further express the context described in the first one.

- 她不但会说中⽂,⽽且还说得很好。

- 他不但没在美国的⼤学学习过,甚⾄连美国都没来过。

- The clauses with the alternative relationship state alternative options.

- 或者跟妈妈⼀起⽣活,或者跟爸爸在⼀起,对我来说都⼀样。

- 我不是上医学院就是读法学院。

- Generally speaking, the order of the clauses in the coordinative relationship or alternative relationship can be changed without affecting the meaning. But the order of the other clauses, successive and progressive, cannot be reversed at will.

- 我⼜喜欢看电视,⼜喜欢听⾳乐。(coordinative)

- 你们或者吃中餐,或者吃⻄餐。(alternative)

- 我不但会开⻋,⽽且会修⻋。(progressive)

- 我妹妹⼀⾼兴就唱歌。 (successive)

- Normally, progressive and alternative clauses should be connected by conjunctions. On the other hand, conjunctions are not always necessary for coordinative and successive clauses.

- 不但他喜欢游泳,我也喜欢。(progressive)

- 这次作⽂写400字还是500字?(alternative)

- 他⼀说完,就⾛了。(successive)

- 我說,你們寫。(successive)

- When the subjects of the two clauses are identical, the second occurrence is usually omitted, and the first is positioned at the beginning of the entire sentence. The conjunctions “不但”, “還是” (“还是”), and “或者” should be placed after the subjects. When the subjects of the two clauses are different, the conjunctions should be placed before the subject.

- 不但⼩王和⼩张是⾼中同学, ⽽且⼩李也跟他们是同学。

- 你们先休息⼀下,下午再学。

- 我们⼀到教室,⽼师就来了。

- The conjunctions that are used to identify the coordinative and alternative relationships, such as “⼜,” “⼀邊” (“⼀边”), “⼀⾯,” “⼀⽅⾯,” “不是,” “還是” (“还是”), and “或者,” can all be used in more than two clauses in a sentence.

- 她总是⼀边吃东⻄,⼀边听⾳乐,⼀边做功课。

- 我或者买蓝⾊的,或者买⿊⾊的,或者买⻩⾊,肯定不买红⾊的。

- When the relationships between the clauses are fairly clear, conjunctions are not necessary, and the conjunction “和” should never be used between the clauses.

- 我是从华盛顿来的,他是从芝加哥來的。

- 你们说,我听。

- The order of the clauses introduced by “不是…⽽是…” cannot be switched without altering the meaning.

- 不是他喜欢那位⼩姐,⽽是他哥哥喜欢她。

- 不是我想学中⽂,⽽是我妈让我学的。

Subordinate Complex Sentences

- Complex sentences formed by clauses in a subordinate relationship are called subordinate complex sentences. In a subordinate complex sentence, the clauses are not equally important in terms of their content.

- The main clause carries the main idea while the subordinate clause only helps to complete the sentence.

- 不管你喜欢不喜欢那些课,你都得上。

- 因为我爸爸和妈妈都不能来接我,所以我去了朋友家。

- Case 1: Adversative—The second clause is the main clause, which may oppose or stand in contrast to the first clause (the subordinate clause).

- 虽然他没有多少钱,但是他还是把那本很贵的书买回来了。

- Case 2: Causative—One clause (the subordinate clause) states the reason or premise while the other clause (the main clause) states the result or inference drawn from the premise.

- 你既然病了,明天就别来上课了。

- Case 3: Conditional—One clause (the subordinate clause) may put forward a condition while the other clause (the main clause) states the resulting action.

- 不管妈妈同意不同意,我都想去旅游。

- Case 4: Hypothetical—One clause (the subordinate clause) puts forward an assumption while the other clause (the main clause) states the result or inference drawn from the assumption.

- 要是你们学习上有问题,就找我。

- Case 5: Purposive—One clause (the subordinate clause) indicates an action for a purpose that is expressed by the other clause (the main clause).

- 爸爸给了我很多钱,以便让我去台湾留学。

- Case 6: Preferential—One clause (the subordinate clause) puts forward an extreme course of action while the other clause (the main clause) indicates another course of action that will be adopted after comparison, i.e., to prefer one course to the other.

- 妹妹宁愿饿死,也不吃爸爸做的饭。

- Subordinate complex sentences are generally made up of two clauses. The order of the clauses normally has the subordinate clause preceding the main clause, but sometimes the main clause comes first, followed by the subordinate clause.

- 因为那所⼤学是公⽴⼤学,所以不太贵。

- 她说芝加哥是⼀个特别漂亮的城市,虽然她从没去过。

- When the subjects of the two clauses are identical, conjunctions are often put at the beginning of the sentence. When the subjects of the two clauses are different, conjunctions are normally put before the subject of the first clause.

- 假如明天我不来上课,你就跟⽼师说我病了。

- When the relationship between the clauses is fairly clear, the corrective in the first clause is often omitted. However, the conjunction in the second clause normally cannot be omitted.

- (就是) 这个周末没有时间,我也会参加朋友的⽣⽇晚会。

Contracted Sentences

- A contracted sentence is a special type of complex sentence that has the structure of a simple sentence. The contracted sentence can express what a complex sentence normally states.

- 我哥哥⾮要买那辆难看的汽⻋不可。

- In a contracted sentence, the two predicates share one subject.

- 他们⼀听说有新电影就很快去了电影院。

- The relationship between the two predicates of the contracted sentence may be coordinative, alternative, progressive, hypothetical, causative, conditional, or successive.

- The predicate functions in contracted complex sentences are often performed by verbs, V-O phrases, V-C phrases, verbal endocentric phrases, or adjectives.

- Both the predicate elements in a contracted complex sentence are brief and compact. This kind of structure is often used in speaking without any pause in between clauses.

- Generally, no comma or semicolon is used. Conjunctions are needed in some contracted complex sentences, while in others they may not be necessary.

- 明天你们⾮做完功课不可。

- 她昨天病了没来上课。

The Conjunctive Adverb “越… 越…”

- The adverb “越” comes before each predicate (a verb or an adjective) as an adverbial adjunct to show that the degree or the state of the second action changes proportionally to the change in the first.

- The first predicate is normally a verb and the second is an adjective or a gradational verb.

- 他们都觉得中⽂越学越容易,可是我怎么越学越难。

- 我在⾼速公路上开⻋越开越慢。

The Conjunctive Adverb “⼀…就 …”

- When the adverbs “⼀” and “就” are used as adverbial adjuncts before predicates, they may denote the successive relationship of actions.

- 你们⼀进这个教室就得说中⽂。

- The predicates following “⼀” and “就” are mainly verbs; however, the predicate after “⼀” denotes a condition and may be an adjective.

- 在我们那个城市,天⼀冷就很难开⻋。

The Conjunction “⾮…不…”

- “⾮…不…” is a “double negative,” emphasizing the meaning “如果不…就 不⾏”, “⼀定要…, 才… .”

- 你明天⾮看医⽣不可。

- The predicate following “⾮” may be a verb, a noun, a pronoun, or a phrase, and the predicate following “不” is often a monosyllabic “可,” or “⾏.”

- 在加州,⾮有⻋不可。