Week 1; intro into atypical development

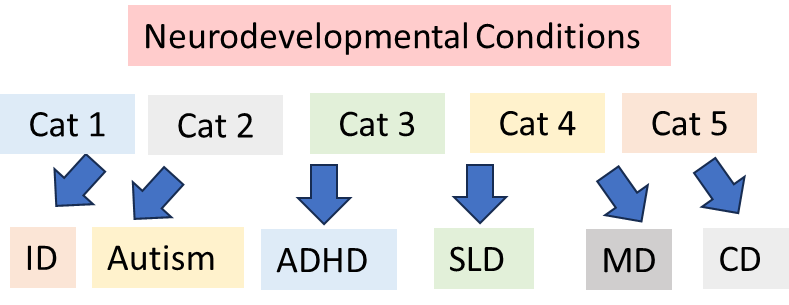

What do we mean by neurodevelopmental conditions?

A neurodevelopmental condition is a lifelong condition that affects how the brain develops and leads to atypical development

Effects can range from mild differences to severe difficulties.

Can be caused by genetic or environmental factors, or a combination of both

Misguided Historical Language

‘Idiocy’ Georget (1795-1828)- Historical terms for Individuals with an Intellectual Disability

‘Imbecile’ (~16th century)- Historical terms for Individuals with an Intellectual Disability

‘Idiots Savants’ Langdon Down (1887)- Patients with exceptional abilities in an extremely narrow field

‘Attentio volubilis’ Weikard (1775)- ‘Easily Rotating’ Patients who are easily distracted/find it hard to maintain attention

The 1900s: a period of change

1913:

‘Mental Deficiency Act’ institutionalisation for children labelled ‘mentally defective’

Cyril Burt – first government appointed psychologist. Worked with London County Council, responsible for identifying ‘feeble minded’ children

Late 1920s

The ‘Commonwealth Fund’ funded child guidance clinics*

1920s & 30s

Expansion of charitable and governmental services for the psychological wellbeing of children

1959:

‘The Mental Health Act’ –The Act emphasized the importance of human rights and dignity for individuals with mental health conditions.

Children were no longer mandatorily institutionalised!

Local authorities were now responsible for their care and many institutions closed. Led to a huge shift in mindset, partially led by parent advocacy – greater understanding was needed to fully understand the appropriate care for different individuals.

1960s-1980s

A largescale movement to universalise neurodevelopmental concepts across psychiatry, psychology and neuroscience

The movement to universalise terms for neurodevelopmental conditions in the 1960s was driven by several key factors:

Growing International Collaboration

Advancements in Research

Need for Standardized Diagnosis and Treatments

Key Points:

The movement towards universal terminology was a significant step in advancing the understanding and of neurodevelopmental conditions.

Official recognition- Intellectual disability had previously been viewed as part of other diagnoses, and not a diagnosis within its own right.

Autism – Leo Kanner, 1943

ADD – American Psychological Association, late 1960s

Down Syndrome – John Langdon Down, 1866

William’s Syndrome – JCP Williams, 1961

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome – David Smith & Kenneth Jones, 1973

Intellectual Disability (standalone) – DSM III, 1980

Historical perspective

reference to different conditions have popped up through historical accounts

not by name but through recognisable descriptions of behaviours

each condition was treated as a discrete, standalone diagnosis until relatively recently

The concept of ‘developmental disorders’ appeared for the first time in 1820 (Georget, 1820)

However, ‘neurodevelopmental conditions’ as a group label didn’t appear in the DSM until the 5th edition in 2013

Now have an understanding of the overlap between different behaviours & characteristics across conditions

Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders:

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the handbook used by health care professionals in the United States and much of the world as the guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders.

Key features:

Diagnostic Criteria: It outlines specific criteria for diagnosing each mental disorder, helping ensure consistency and reliability in diagnosis.

Common Language: The DSM provides a common language for clinicians to communicate about their patients and establish consistent and reliable diagnoses.

Research Tool: The DSM is used in research on mental disorders to track prevalence, study risk factors, and evaluate treatment effectiveness.

DSM-III (1980)- several factors contributed to the inclusion of the category ‘developmental' conditions’ (not yet called ‘neurodevelopment’ in the DSM-III:

Growing Recognition and research:

Increased scientific research and a growing understanding of neurodevelopmental conditions led to greater recognition of their distinct characteristics and impact.

This provided the foundation for developing specific diagnostic criteria.

Need for consistency and reliability:

Prior to DSM-III, diagnoses were often inconsistent and varied significantly between clinicians.

The need for a standardised system for diagnosing and classifying these conditions was crucial for improving communication, research, and treatment planning

The DSM-III's emphasis on observable and measurable behaviours aimed to increase the objectivity and reliability of diagnoses

Advocacy efforts:

Advocacy groups and families of individuals with neurodevelopmental conditions played a crucial role in raising awareness and advocating for their inclusion in the DSM-III.

DSM-III: categorical approach

Learning disorders e.g. dyslexia, dyscalculia

Mental Retardation e.g. Down Syndrome, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

motor skills disorders e.g. Tourette’s, cerebal palsy, dyspraxia

communication disorders e.g. stuttering, specific language impairments

pervasive developmental disorders e.g. autism, Rett Syndrome

DSM-IV-R (2013)

The DSM-5-R recognizes that many developmental disorders have underlying neurological and biological origins.

It groups conditions into one broad category of ‘neurodevelopmental conditions’, including:

Intellectual Disability

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Specific Learning Disorder

Motor Disorders (including Tic Disorders)

Communication Disorders

This is important as it acknowledges that many conditions share behaviours i.e. could belong to more than one of the categories in the earlier DSM-III

A note about language/ context

Atypical development should not necessarily be viewed negatively. But it’s also important to recognise the difficulties that people can experience.

“Difference” vs “Disorder”

Don’t lose sight of the fact that diversity is important!

Traditionally, a lot of negative language: “impairment” “deficit”. More appropriate to use terms such as “condition” “difference”

Important to respect individual perspectives. Listen to those who are “experts-by-experience”. Avoid falling into ‘othering’.

Current discussions around ASC show increasing awareness of these issues – led predominantly by autistic people.

Person-first language, e.g. “person with autism” or identity-first language, e.g. “autistic person”.

Multiple reasons for atypical development

Pre-natal effects (e.g. exposure to teratogen)

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

Environmental effects (e.g. complications during birth)

Cerebral Palsy

Genetic effects

Hereditary

Spontaneous mutations (e.g. Copy Number Variants), no history of the condition in family

Unknown (likely multifaceted) effects:

we just do not know what the causes are, there seems to be multiple so we can’t pinpoint to just one

Autism Spectrum Conditions

ADHD

intellectual disability

Genetics

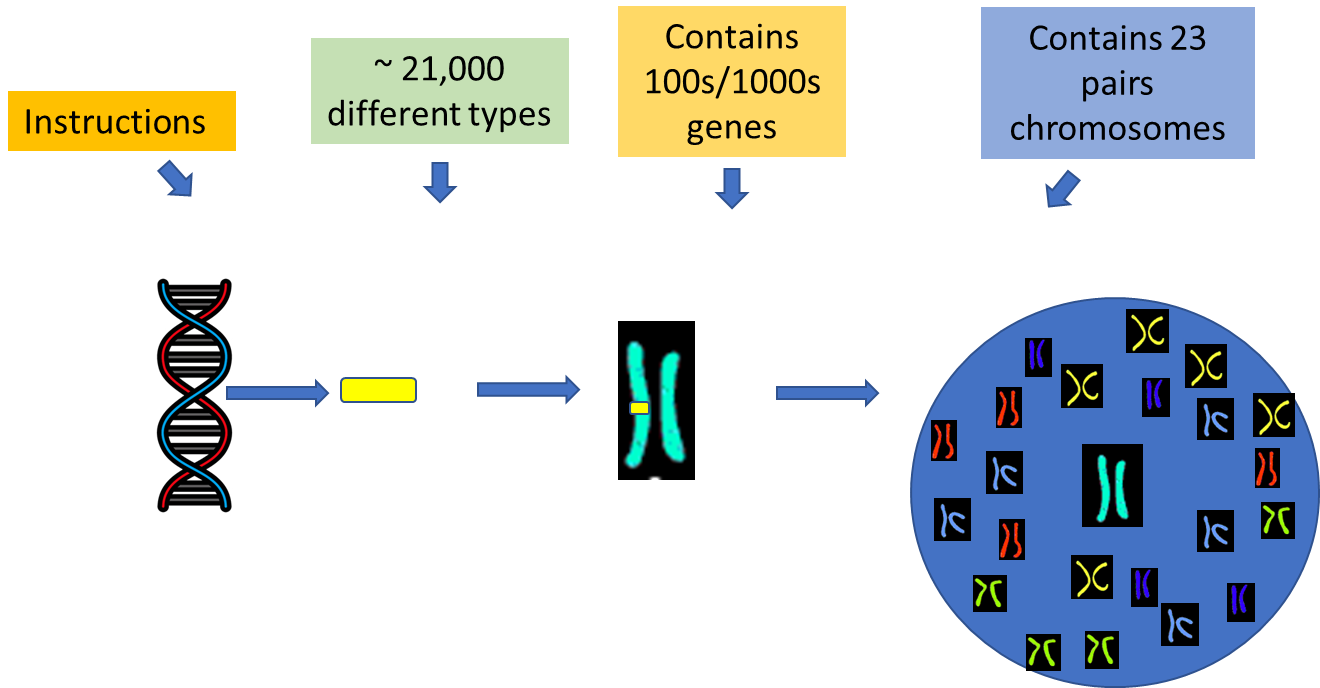

Basic genetics

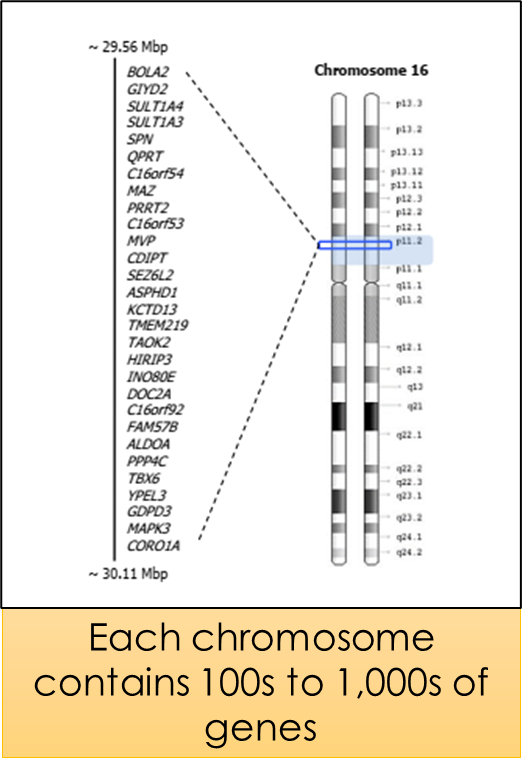

Every cell in our body contains DNA → DNA contains ‘instructions’ for building proteins. This is the basis for all of our development: the entire structure and function of the body is governed by the types and amounts of proteins the body synthesizes. → DNA is packaged into genes. Humans have about 21,000 different genes. → Genes are contained in chromosomes. Each chromosome contains 100s to 1000s of genes

DNA > Genes > Chromosomes > cell

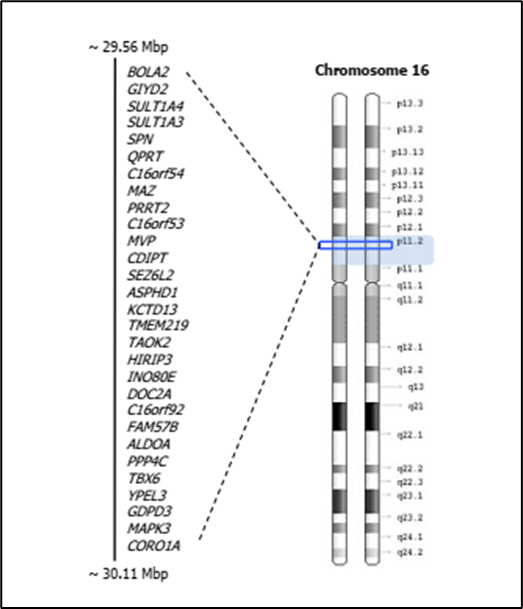

How do geneticist label particular parts of the chromosome?

Chromosome Region: Chromosome regions are labelled with numbers, with lower numbers representing a region of the chromosome that is closest to the centre.

Basic Genetics: chromosomal abnormalities that can lead to atypical development

This diagram shows that in just this small section of chromosome 16, there are 29 different genes.

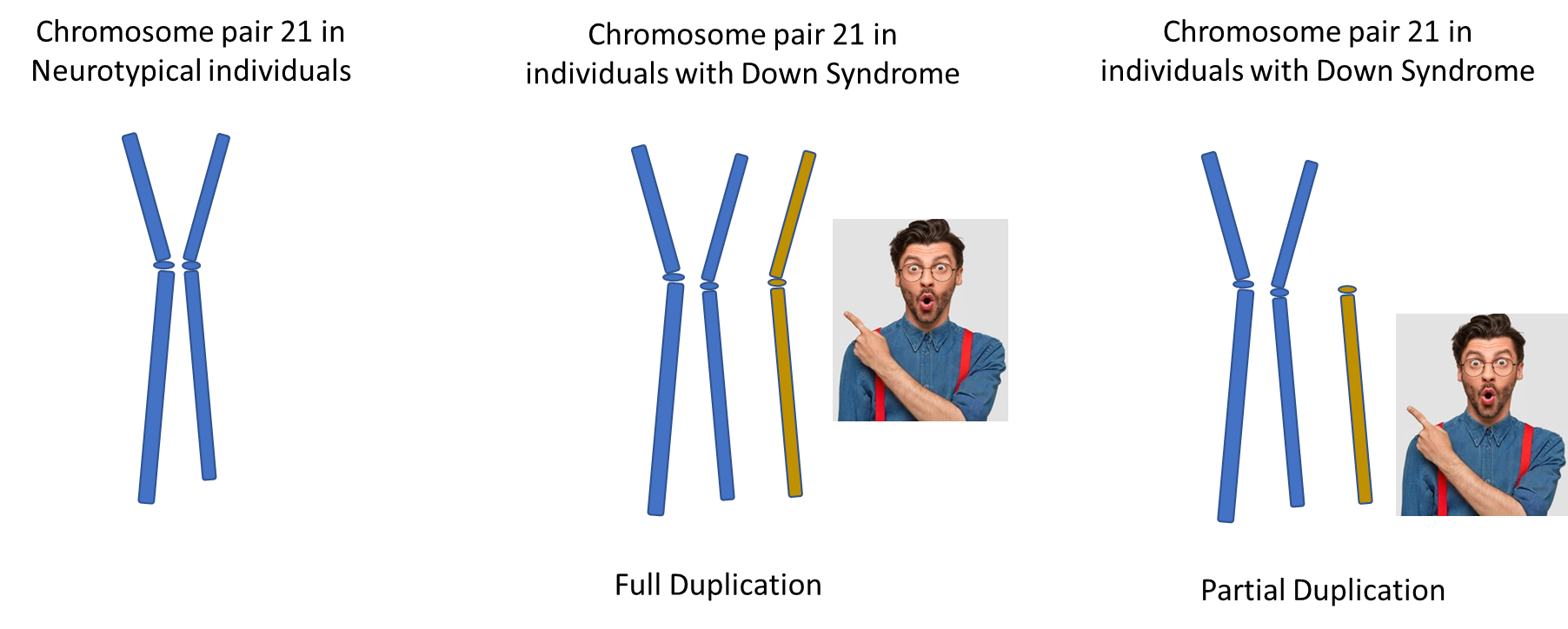

Genetic Abnormalities can occur when there are either too many or too few occurrences of particular genes. This can happen in various ways, for example, some people have extra chromosomes (e.g. in Down’s syndrome), whereas other people can have parts of chromosomes that are either duplicated or deleted.

Common forms of chromosomal abnormalities include addition of a chromosome.

For example, people with Down’s syndrome have an additional copy of chromosome 21.

Other examples of chromosomal abnormalities include duplication or deletion of a certain part of the chromosome. This means that there are extra copies of some genes (duplication) or missing copies of some genes (deletion). These are called COPY NUMBER VARIANTS (CNVs)

Genetic abnormalities→ too many or too few of particular genes resulting from:

•Extra chromosome (e.g. Down’s Syndrome)

•Duplication of a certain part of a chromosome (e.g. 16p11.2)

Deletion of a certain part of a chromosome (e.g. William’s Syndrome)

Examples of Atypical

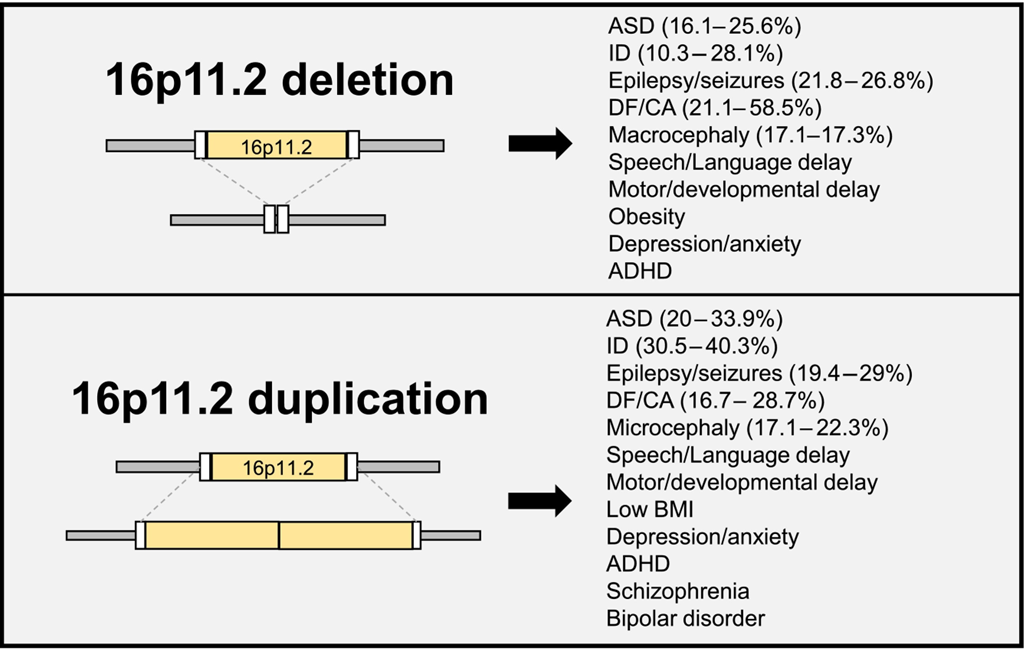

16p11.2:

16p.11.2 deletions and duplications have come under research scrutiny recently due to their association with a range of developmental conditions including ADHD, autism, intellectual disability, as well as anxiety and OCD

varied presentation:

Leads to developmental delay, autism, intellectual disability in some,

But in others remains undetected due to no physical or developmental symptoms

Generally, only detected when children come to clinic with signs of developmental delay and autistic features.

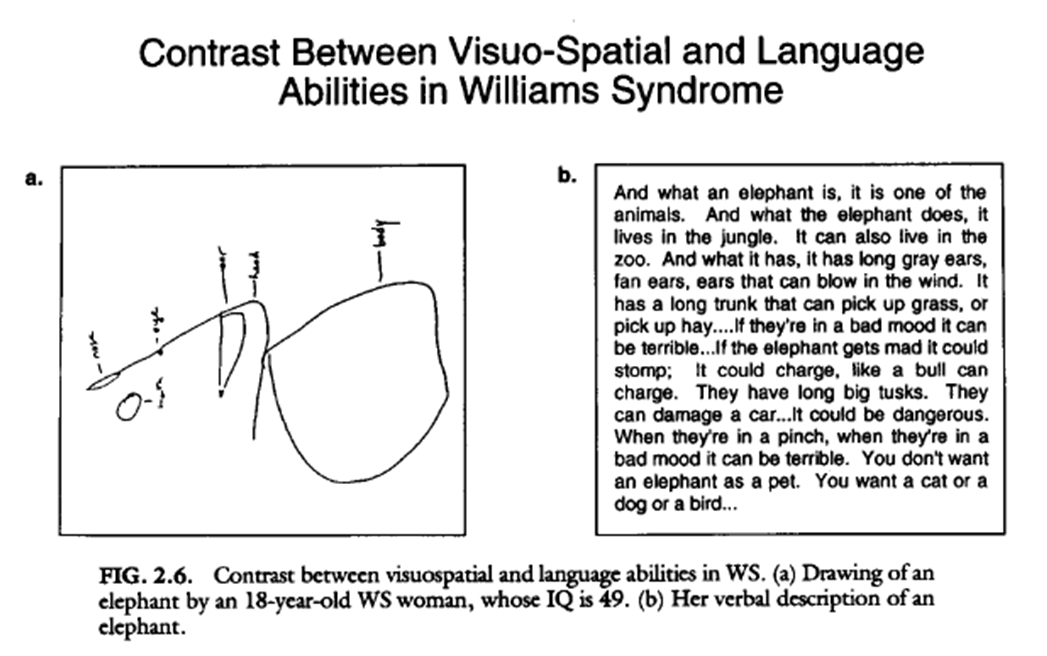

William’s Syndrome:

Caused by spontaneous deletion at chromosome 7q11.2.

Characterized by a distinct facial appearance, cardiac anomalies, highly sociable personality, atypical cognitive profile, and connective tissue abnormalities.

Is rare: affects ~ 1 in 10,000 people

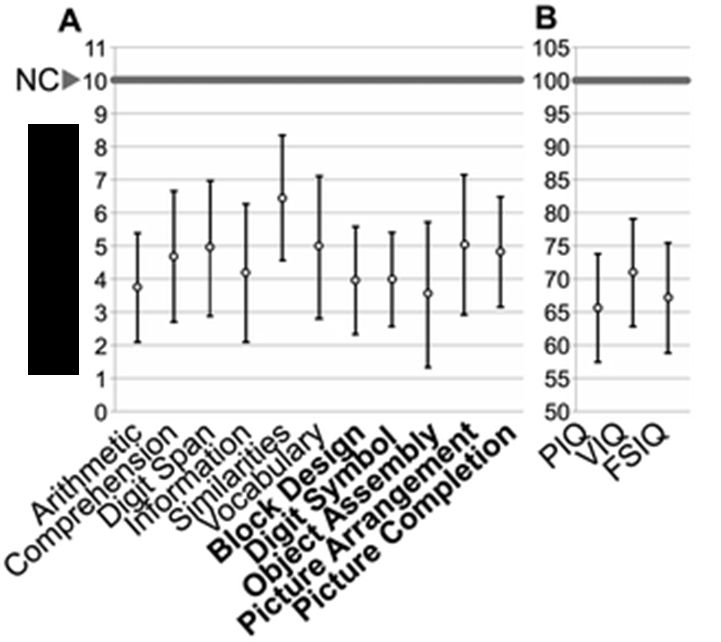

Cognitive profile of William’s Syndrome

WS characterised by strengths in verbal IQ, compared with performance (visuospatial) IQ

What is Down Syndrome?

Caused by a duplication of Chromosome 21

Characteristics of down syndrome

physical characteristics

Decreased or poor muscle tone

Shorter neck

Flattened facial profile and nose

Upward slanting eyes

Wide, short hands with short fingers

A single, deep, crease across the palm of the hand

cognitive characteristics

Short attention span

Impulsive behavior

Slow learning

Delayed language and speech development

Variable IQ (average between 30 -70)

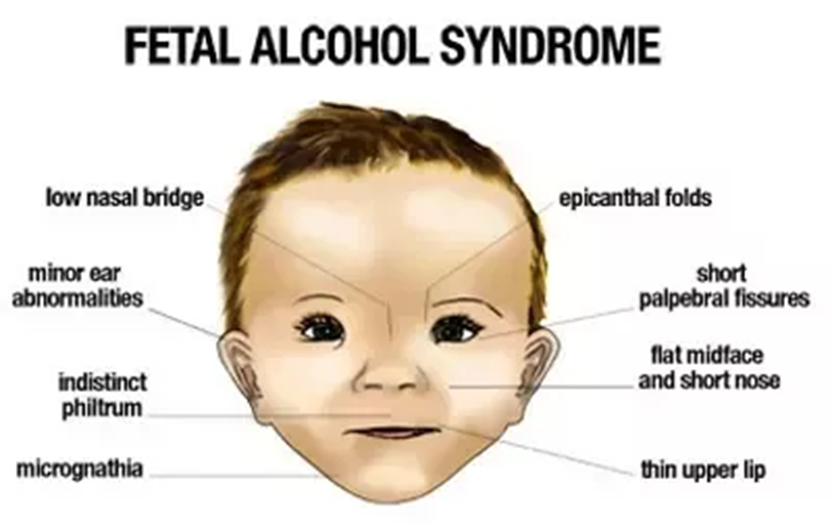

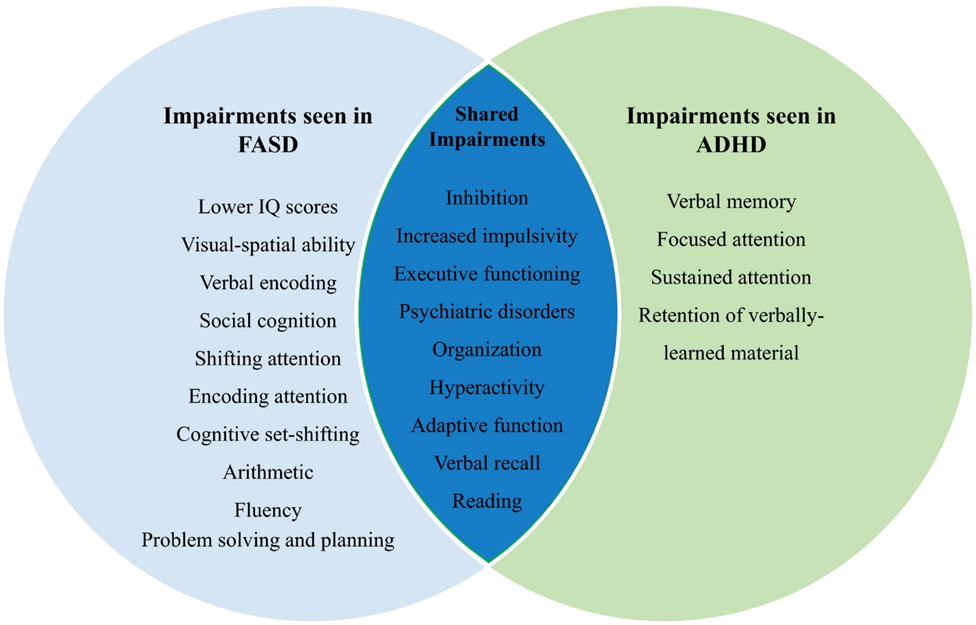

Mechanisms of FASD

Alcohol is a teratogen (an agent which causes change in an embryo).

Not clear on the amount of alcohol needed to lead to FASD.

Depends on when during the gestation period alcohol is consumed.

Binge drinking (4 drinks in 2 hours) leads to more severe symptoms.

Prevalence estimates suggest about 2% - 3% of elementary school children in Ontario, Canada have FASD.

Ethanol (compound within alcohol) thought to alter DNA and protein synthesis and inhibit cell migration, leading to an array of physical and cognitive changes.

Fetal Alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD)- FASD is a diagnostic term describing the constellation of effects that result from prenatal alcohol exposure.

diagnostic criteria

Abnormal facial features, such as a smooth ridge between the nose and upper lip.

Small head size (microcephaly)

Shorter-than-average height

Low body weight

Poor coordination

Hyperactive behaviour

Difficulty with attention

Poor memory

Difficulty in school

Learning disabilities

Speech and language delays

Intellectual disability or low IQ

Poor reasoning and judgment skills

Sleep and sucking problems as a baby

Vision or hearing problems

Problems with the heart, kidneys, or bones

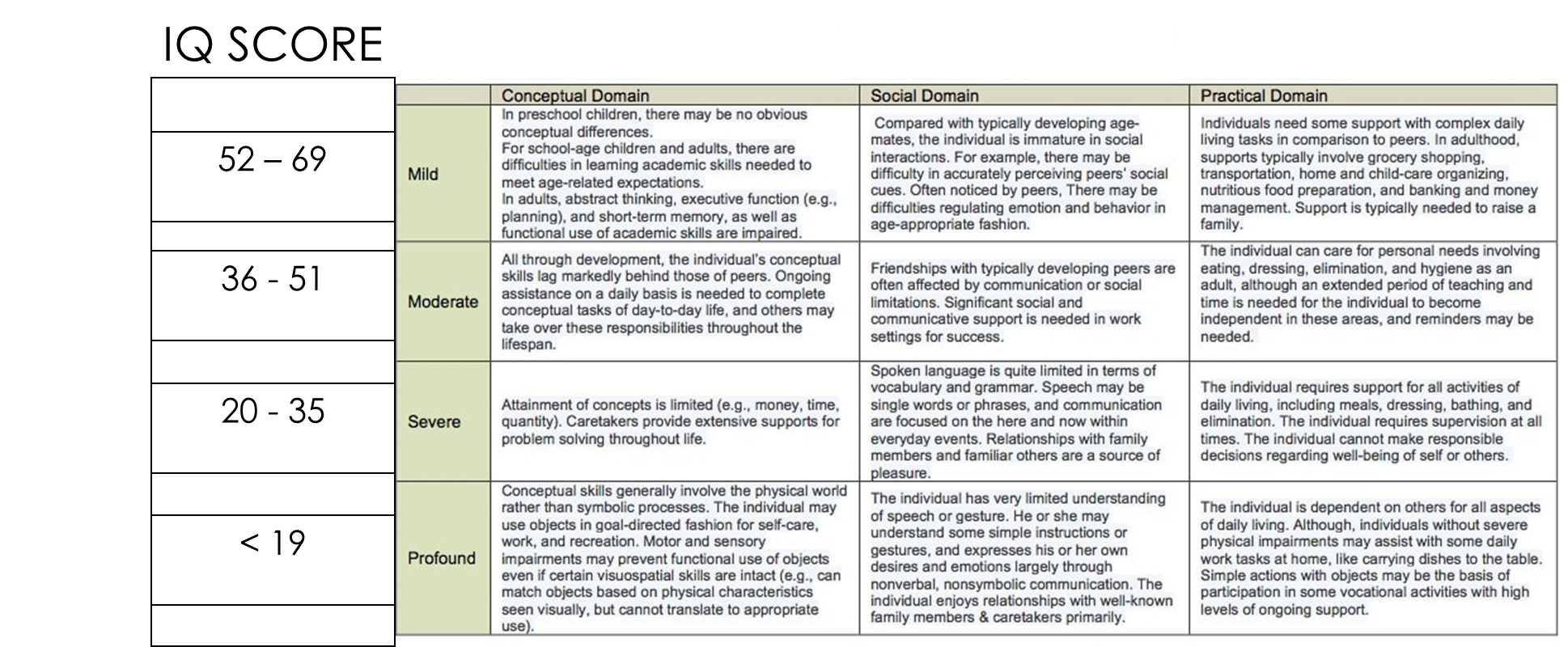

Intellectual disability

Is a diagnosis in its own right, but also often co-occurs with other neurodevelopmental conditions, e.g. autism, FASD, specific genetic conditions.

Affects ~ 10.4 people in every 1000 (1.4%).

Diagnosis based on IQ evaluation as well as investigation of adaptive behaviour, and classified as mild (52-69 IQ), moderate (36-51 IQ), severe (20-35 IQ) or profound (<19 IQ).

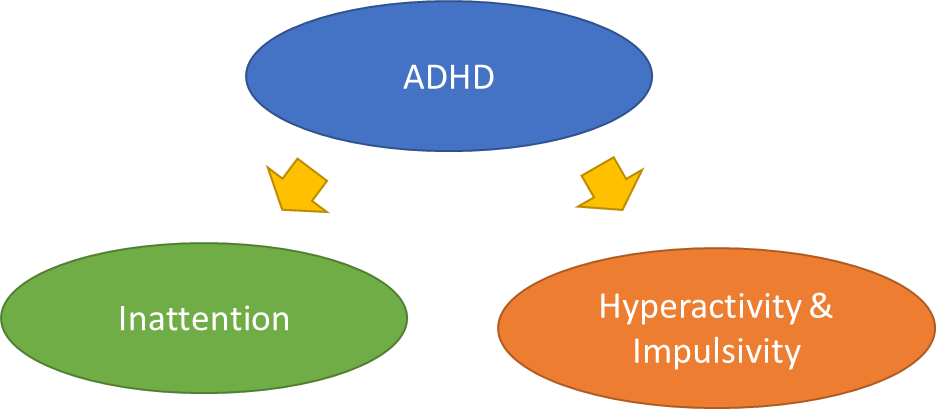

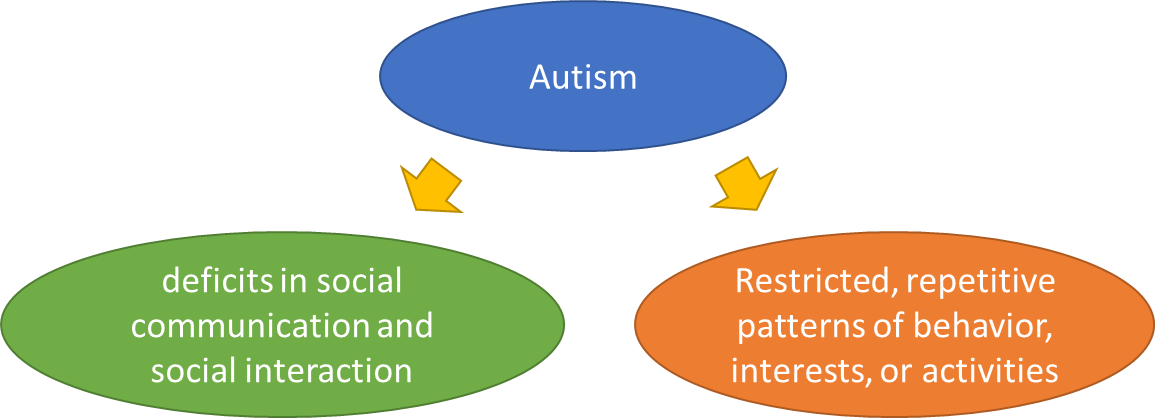

ADHD & Autism

No clear cause for either ADHD or Autism

Likely caused by numerous contributing factors

As there is no clear cause there isn’t a definitive test as with genetic conditions

Diagnosis is made by behavioural observations

Check if behaviour matches the criteria laid out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

Reading

The history of language used to describe autism

The term ‘autism’ emerged in the early 20th century through Eugen Bleuler’s observation that some schizophrenic ‘patients’ had withdrawn from social contact and appeared to be living in their own world. Then, in the 1940s, the term was first used to represent children with particular behavioural characteristics. The term was included in the of the DSM-III in 1980. Throughout this time, autism was generally conceptualised by clinicians through a medical model lens as being abnormal and, thus, clinical efforts often focussed on ‘curing’ the person.

Over the past 30 years, this medical model stance on autism has been challenged by the autistic self-advocacy movements, which view autism as a part of the natural spectrum of human diversity and, thus, an inseparable aspect of identity.

Aligning with the social model of disability, the neurodiversity paradigm attributes the disabilities associated with autism to the interactions between autistic characteristics and an environment that imposes structural, systemic, and social barriers.

In conceptualising autism as a neurological difference rather than a disorder, research efforts focus on creating more inclusive environments to enhance autistic well-being and quality of life.

Historically, most autism research has been carried out without input from autistic people. Research often described autism using medicalised, pathologising, and deficit-based language (e.g., disorder, impairment, or cure) and person-first language (e.g., child with autism). The use of this terminology has been criticised by neurodivergent scholars, who advocated strongly that it can have negative consequences for how society views and treats autistic people and can even influence how they view themselves.

Language use in autism research

The wider autism communities, including clinicians and researchers, have an important role in promoting autistic-preferred language and centralising autistic perspectives.

Many of the ‘potentially offensive’ terms portray a medical/deficit focussed view of autism. These terms imply there is something ‘wrong’ with the autistic individual, that autistic individuals have to be ‘cured’, and/or that they are inferior in some way to non-autistic people.

Importantly many would argue, these supports should not try to change, or ‘intervene’ in, autistic ways of being, or target a skill (e.g.,eye contact) to ‘normalise’ the autistic person relative to their peers. For example, clinicians could support the use of augmentative and alternative communication methods, such as a speech-generating device or sign language, rather than focussing solely on allistic speech bench marks.

Similar considerations apply to basic research. For example, when modelling the neurobiological basis of co-occurring conditions and genetic conditions with higher co-occurrence with autism (e.g., Fragile X syndrome), researchers must not conflate these conditions and models with autism itself. Authors should also avoid making statements about ‘autistic behaviours’ in animal models, because any specific behaviour in animals does not correspond to complex expressions in humans. It is especially inappropriate to attempt to model ‘autism characteristics’ in animals with the intention of preventing or curing autism itself.

Views on terminology are highly individual; thus, during personal interactions, the language used should always respect an autistic person’s preferences. However, the differing perspectives of autistic individuals should not be used to justify ignoring the preferences shared by most of the autistic community in autism research. For example, while some autistic people express preference for person-first language ( 'people with autism’), identity-first language (e.g.,‘autistic people’) has been preferred by most autistic people

layout: potentially offensive, autistic preferred, insight and perspectives from the autistic community, example of preferred language use in research

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Autism, autistic

Disorder is unnecessarily medicalised and reinforces negative discourses that autism is wrong or needs curing

‘Autism is a neurodevelopmental difference…’

Person-first language (person with autism)

Identity-first language [autistic (person)]

Identity-first language emphasises autism as inseparable from the person and an integral part of their identity, where as person-first language suggests a separation between autism and the individual

‘A total of 125 autistic adults participated in the study.’

Autism symptoms and impairments

Specific autistic experiences and characteristics

Medical terminology pathologises the characteristics and experiences of autistic people as deficient and abnormal

‘This study recruited autistic participants with a high sensitivity to sensory stimuli.’

At risk of autism

May be autistic; increased likelihood of being autistic Danger-oriented terms (vs. probabilistic terms) imply that autism is a negative (possibly preventable) outcome

‘Children with an increased likelihood of being autistic were also included in the study.’

Co-morbidity

Co-occurring

Autism is not a disease, even though it often co- occurs with other neurodivergences or medical conditions

‘Individuals with co-occurring medical conditions were excluded from the study.’

Functioning (e.g., high/low functioning) and severity (e.g.,mild/moderate/severe) labels

Specific support needs

All autistic people have a range of strengths, skills, challenges, and support needs that can vary over time and in different situations and environments

‘Individuals with sensory and communication support needs.’

Cure, treatment, or intervention

Specific support or service

Autism does not need to be cured, treated, or modified. Supports should not be targeted at autism characteristics, although autistic people may benefit from individualised supports

‘The participants were receiving occupational therapy to reduce sensory overload in those with high sensory needs.’

Restricted interests and obsessions

Specialised, focussed, or intense interests

Deficit-based terminology pathologises the interests of autistic people rather than celebrating their knowledge

‘The participant had specialised interests in computers and politics.’

Normal person

Allistic or non-autistic

Allistic is an empowering term that reframes autism and autistic traits as a difference instead of an abnormality

‘The comparison group included allistic(non-autistic)people.