Renaissance music study guide

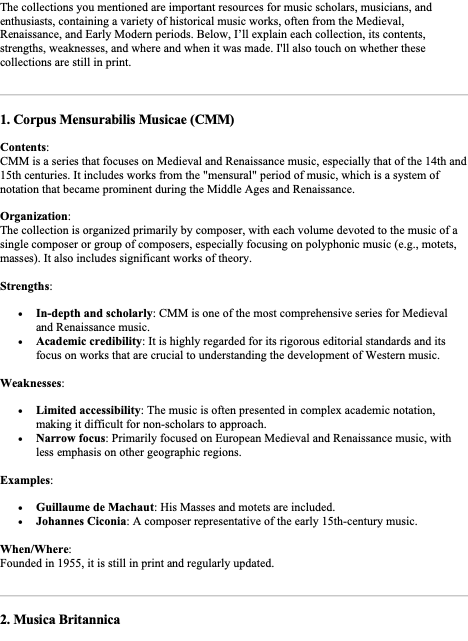

The collections you mentioned are important resources for music scholars, musicians, and enthusiasts, containing a variety of historical music works, often from the Medieval, Renaissance, and Early Modern periods. Below, I’ll explain each collection, its contents, strengths, weaknesses, and where and when it was made. I'll also touch on whether these collections are still in print.

1. Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae (CMM)

Contents:

CMM is a series that focuses on Medieval and Renaissance music, especially that of the 14th and 15th centuries. It includes works from the "mensural" period of music, which is a system of notation that became prominent during the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Organization:

The collection is organized primarily by composer, with each volume devoted to the music of a single composer or group of composers, especially focusing on polyphonic music (e.g., motets, masses). It also includes significant works of theory.

Strengths:

In-depth and scholarly: CMM is one of the most comprehensive series for Medieval and Renaissance music.

Academic credibility: It is highly regarded for its rigorous editorial standards and its focus on works that are crucial to understanding the development of Western music.

Weaknesses:

Limited accessibility: The music is often presented in complex academic notation, making it difficult for non-scholars to approach.

Narrow focus: Primarily focused on European Medieval and Renaissance music, with less emphasis on other geographic regions.

Examples:

Guillaume de Machaut: His Masses and motets are included.

Johannes Ciconia: A composer representative of the early 15th-century music.

When/Where:

Founded in 1955, it is still in print and regularly updated.

2. Musica Britannica

Contents:

Musica Britannica is a series that focuses on English music, particularly from the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. The collection contains both vocal and instrumental music from English composers.

Organization:

The works are organized by composer, with a particular focus on English church music, including anthems, motets, and madrigals.

Strengths:

Focus on English composers: It offers important works by lesser-known composers, contributing to the understanding of England's musical history.

Reliable editions: Known for well-researched and clear editions of works, many of which were previously unavailable in modern notation.

Weaknesses:

Limited scope: Primarily focuses on English music, so it may not be useful for those seeking a broader European context.

Vocal music-heavy: A larger portion of the collection is dedicated to choral works, which may not appeal to all instrumentalists.

Examples:

Thomas Tallis: His choral works like Spem in Alium.

William Byrd: Known for his sacred choral music.

When/Where:

Founded in 1951, still in print with ongoing releases.

3. Das Erbe deutscher Musik

Contents:

This series focuses on German music, especially from the Baroque and Classical periods. It includes both well-known composers as well as more obscure figures who contributed significantly to the development of German music.

Organization:

The collection is organized both by composer and genre, including sacred and secular music, orchestral and choral works, as well as instrumental music.

Strengths:

Deep dive into German music: Offers a detailed exploration of the German musical tradition, particularly useful for those interested in the classical and early romantic periods.

Varied content: Includes both well-known masterpieces and lesser-known works.

Weaknesses:

Focus on German music: Like many other specialized collections, its narrow geographic focus can limit its broader applicability.

Heavy focus on classical and early Romantic music: May not be of as much use for those researching later periods.

Examples:

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: His keyboard and orchestral works.

Georg Philipp Telemann: Known for his instrumental and orchestral music.

When/Where:

Founded in 1928, this series is still in print and continues to be a key resource for German music.

4. Monumentos de la Música Española (MME)

Contents:

MME is dedicated to Spanish music, focusing primarily on works from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. It includes sacred music, instrumental music, and polyphonic choral works.

Organization:

The collection is organized by composer, but there are also volumes that provide thematic collections of music from different regions of Spain.

Strengths:

Focus on Spanish music: Provides insight into a rich and often underrepresented musical tradition.

Diversity of genres: Includes a wide variety of styles, from Renaissance polyphony to Baroque instrumental music.

Weaknesses:

Narrow geographic focus: Like other national series, the scope is limited to Spanish music.

Specialized audience: Most accessible to those specifically studying Spanish music or those interested in this particular national tradition.

Examples:

Tomás Luis de Victoria: A composer of sacred choral music.

Francisco Guerrero: Known for his polyphonic works.

When/Where:

Founded in 1955, still in print and ongoing.

5. A-R Editions: Recent Researches in the Music of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance (RRMME)

Contents:

This collection offers scholarly editions of Medieval and early Renaissance music, primarily focusing on manuscripts and lesser-known compositions.

Organization:

The works are organized chronologically and regionally, often with a focus on smaller-scale works, particularly motets, chants, and other polyphonic forms.

Strengths:

Focus on recent research: Provides editions based on the most up-to-date research in the field.

Exploration of lesser-known works: Highlights rare and significant pieces that are often overlooked in other collections.

Weaknesses:

Niche appeal: The focus on early music can make it less accessible to those interested in later periods.

Complexity of notation: As with other scholarly collections, the music may be presented in complex formats that require a certain level of expertise.

Examples:

Petrus de Cruce: A composer of early polyphonic music.

Guillaume de Machaut: Works like his motets and the Messe de Nostre Dame.

When/Where:

Launched in 1980 and continues to be in print, with ongoing new volumes.

6. A-R Editions: Recent Researches in the Music of the Renaissance (RRMR)

Contents:

This series presents scholarly editions of Renaissance music, with a particular emphasis on both well-known and lesser-known composers. It includes polyphonic vocal music, instrumental works, and liturgical music.

Organization:

Works are organized by composer and sometimes by genre or region.

Strengths:

Comprehensive scholarly editions: Known for offering rigorously researched and highly detailed musical editions.

Focus on lesser-known composers: It brings attention to important but often neglected works.

Weaknesses:

Highly academic: Requires advanced knowledge of music theory and historical context.

Limited appeal outside of scholarly contexts: Primarily useful for musicologists or performers in early music ensembles.

Examples:

Josquin des Prez: His motets and masses.

Orlando di Lasso: Known for his polyphonic choral music.

When/Where:

Started in 1978, still ongoing and in print.

7. Corpus of Early Keyboard Music (CEKM)

Contents:

CEKM focuses on early keyboard music, including works from the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. It covers both organ and harpsichord music.

Organization:

The collection is organized by composer, with some volumes dedicated to specific genres, such as dance suites or keyboard variations.

Strengths:

Focus on keyboard music: It offers a deep exploration of early keyboard traditions.

Variety of composers: Includes works from famous composers, but also lesser-known figures.

Weaknesses:

Limited to keyboard music: It does not include vocal or orchestral works.

Narrow time frame: Focuses primarily on early music, so it may not be useful for those interested in later keyboard works.

Examples:

Johann Sebastian Bach: Early works for harpsichord and organ.

Orlando Gibbons: Known for his keyboard works and motets.

When/Where:

First published in the 1980s, still in print and continues to release new volumes.

Summary

All these collections are scholarly editions designed for academic use, and most are still in print. They offer valuable resources for studying specific historical periods and regions of music but can be difficult for general audiences due to their academic focus and notation. They are often considered essential for anyone researching the music of these specific periods and places.

Difference between Manuscript, Facsimile, Critical Edition, and Performing Edition

Manuscript:

Definition: A manuscript is an original hand-written document, typically produced before the invention of the printing press. In music, it refers to handwritten musical scores.

Example: A manuscript of a motet by Josquin des Prez, written in the 15th century by a scribe for a specific patron or institution.

Characteristics: Often contains unique notations, sometimes incomplete or with mistakes, and can vary from one copy to another.

Facsimile:

Definition: A facsimile is a photographic reproduction of a manuscript or original source, often produced to preserve or share a rare or fragile document. The aim is to present an exact copy of the original.

Example: A facsimile of the Codex Buranus, a manuscript containing medieval songs and poems.

Characteristics: It provides an exact replica, preserving the appearance, layout, and ink of the original manuscript, including any mistakes or anomalies.

Critical Edition:

Definition: A critical edition is a scholarly version of a musical work (or text) that reconstructs the most accurate version of the work, based on careful analysis of multiple sources, such as manuscripts and early printed editions. Editors resolve discrepancies and offer notes on variants or editorial decisions.

Example: The critical edition of L'Orfeo by Claudio Monteverdi, produced by musicologists who examined various surviving manuscripts and early prints to reconstruct the score.

Characteristics: It includes an extensive introduction, footnotes, and sometimes alternative readings, explaining editorial choices and providing historical and musical context.

Performing Edition:

Definition: A performing edition is a version of a musical work that is specifically tailored for performance. It may simplify or adapt the original material, updating notations or providing practical solutions for modern performers.

Example: A performing edition of a Renaissance madrigal, where modern notations (such as key signatures and contemporary rhythms) are used to help performers.

Characteristics: It might involve alterations to the original score, like added dynamics, articulations, or modernized notation, to make it easier to perform, especially for musicians today.

Example of a Primary and Secondary Source in Renaissance Studies

Primary Source:

Example: The Trent Codices (1510s–1520s). This is a collection of Renaissance polyphonic music, including works by composers like Josquin des Prez and Heinrich Isaac, preserved in the library of the cathedral in Trent. It provides direct access to music as it was written and performed during the Renaissance period.

Explanation: It is a direct source from the Renaissance, a manuscript that reflects the music of that era and offers a glimpse into the musical practices and culture of the time.

Secondary Source:

Example: Music in the Renaissance by Gustave Reese (1954). This is a scholarly book that discusses the music of the Renaissance, providing analysis, historical context, and interpretations of primary sources.

Explanation: As a secondary source, it synthesizes information from primary sources and presents it in a narrative or analytical form for educational purposes, offering insight into the significance and development of music during the Renaissance.

Medieval or Renaissance Treatise

Treatise: De institutione musica (On the Principles of Music)

Author: Boethius (c. 480–524 AD)

Date: Written c. 500 AD (though its influence lasted well into the Medieval and Renaissance periods)

Subject(s) Covered:

Musical Theory: De institutione musica covers the theoretical foundations of music, defining music as a science and exploring its mathematical and philosophical aspects. Boethius describes the three types of music: musica mundana (the music of the spheres), musica humana (the harmony of the human body and soul), and musica instrumentalis (the music created by instruments and voices).

Numerical and Mathematical Basis: It outlines the principles of harmony and the mathematical relationships between pitches, particularly focusing on the ratios that govern musical intervals (such as the perfect fifth and octave).

Ethical and Philosophical Aspects: Boethius explores the ethical implications of music, drawing on the ideas of ancient Greek philosophers like Pythagoras and Plato. He discusses the moral influence of music on the human soul.

Importance and Influence:

Influence on Medieval and Renaissance Music: Boethius' De institutione musica was one of the most important musicological texts in the Medieval period and continued to shape musical thought into the Renaissance. Its ideas were foundational to medieval music theory and were central to the study of music in cathedral schools and universities. For centuries, Boethius’ work was considered the authoritative text on music theory.

Philosophical Impact: His treatise influenced the Renaissance scholars who sought to reconnect music theory with its philosophical and mathematical roots, forming a bridge between the classical and medieval understandings of music.

Intended Audience:

Philosophers, Scholars, and Clergy: Boethius wrote for an intellectual audience, including theologians, philosophers, and musicians in the monastic and academic settings. His work was intended to bridge the gap between classical Greek and Roman music theory and the Christian intellectual tradition.

Educational Role: It served as an educational text in monasteries and later universities, where it was used to teach both music theory and the philosophical aspects of music, including its connection to ethics and the cosmos.

Conclusion:

De institutione musica was crucial not only for its contributions to music theory but also for its role in preserving the ideas of classical antiquity throughout the Middle Ages. Its influence can be seen in both the philosophical and practical aspects of Medieval and Renaissance music, laying the groundwork for later developments in musicology and composition.

Instruments and Ensembles in the Renaissance

1. Loud Ensemble / Alta Capella / Haut

Definition: The alta capella (Italian: alta meaning "high") refers to the loud wind and percussion ensemble of the Renaissance, typically used for outdoor and ceremonial occasions. Instruments in this ensemble are designed to produce a strong, brash sound suitable for large spaces or outdoor performances.

Instruments: Common instruments in the alta capella include:

Shawm (the precursor to the oboe)

Sackbut (a precursor to the trombone)

Trumpet

Percussion (like the tabor or nakers)

Function: These ensembles were often used in processions, military settings, or large public events. The loud, bold sound was meant to carry long distances.

2. Soft Ensemble (Bas)

Definition: The soft ensemble, also known as bas (French for "low"), consisted of instruments that produced quieter sounds suitable for indoor and more intimate settings.

Instruments: Common instruments in the bas ensemble include:

Lute

Viol (especially the treble viol and bass viol)

Recorder

Flute

Harp

Crumhorn (though this could be used in both soft and loud contexts)

Fiddle (early string instruments)

Function: The bas ensemble played music for domestic entertainment, courtly performances, or chamber music. It often accompanied vocal music, and its softer tone was more appropriate for indoor settings.

3. Consort

Definition: A consort refers to a group of instruments from the same family, typically played together. A broken consort consists of different types of instruments, such as strings and winds, while a whole consort consists of instruments from one family (e.g., all viols or all recorders).

Instruments: Examples include:

Whole consort: A consort of viols (e.g., treble, tenor, and bass viols).

Broken consort: A consort of viols, flutes, and lutes.

Function: Consorts were popular in Renaissance chamber music and were used for both instrumental compositions and for accompanying vocal music. Composers like John Dowland and William Byrd wrote works for consort, particularly in the court and private home settings.

Combinations of Instruments in the Renaissance

The Renaissance period saw many combinations of instruments, both in ensembles and in the accompaniment of vocal music. Some combinations include:

Vocal + Soft Ensemble: A common pairing where a singer would be accompanied by lutes, viols, or the harpsichord.

Vocal + Loud Ensemble: Especially for larger-scale public performances, processions, or ceremonial events, where brass instruments, shawms, and percussion would accompany vocalists.

Instrumental Consorts: Mixed ensembles of viols, flutes, or lutes playing instrumental music. This was especially popular in courtly settings or private chambers.

Keyboard + Instruments: The harpsichord was often paired with other instruments such as viols or lutes in chamber settings, or used to accompany vocal music.

15th Century Song Accompaniment

Instruments: During the 15th century, vocal music was often accompanied by instruments like the lute, organ, harp, viol, and flute. These instruments were used to provide harmonic support, fill in the texture, and offer a melodic or contrapuntal line to support the voice.

Evidence: We have evidence of this practice from manuscripts, such as those from the Flemish school, which often included lute accompaniments. One important example is the “Chansonnier de Saint-Germain-des-Prés”, which shows lute and vocal accompaniment.

Types of accompaniment: In many cases, the accompaniment would follow the vocal melody (often in a simple style), but in more sophisticated settings, instruments would add harmony or provide a more independent counterpoint to the voice.

In-Depth Study of the Harpsichord

Sound:

The harpsichord produces sound by plucking the strings with quills (or sometimes leather), unlike the piano, where the strings are struck with hammers. This produces a bright, percussive sound.

The harpsichord's sound is distinct from the modern piano because it lacks dynamic variation—its volume is fixed depending on the force of the plucking mechanism. This makes it ideal for the Renaissance, where subtle dynamic nuances were less of a focus.

Construction:

The harpsichord has a rectangular wooden body, with a keyboard and strings inside. The strings are generally made of metal and stretched across a soundboard.

The number of manuals (keyboards) can vary, typically one or two. The larger the harpsichord, the more strings and manuals it may have.

The action of the keys (the mechanism by which they pluck the strings) is crucial for the instrument’s response. Many early harpsichords have a light and fast action, allowing for rapid articulation of notes.

Tuning:

Renaissance harpsichords were tuned according to various temperaments. The most common tuning system was meantone tuning, where certain keys sounded more in tune than others.

Mean tone tuning allowed for pure thirds, but it created problematic intervals in certain keys, which meant some keys sounded out of tune.

Performance Techniques:

Harpsichordists would use a technique called finger articulation to ensure that each note was cleanly separated, and could use different registrations (switching between sets of strings) to vary the timbre.

Bach’s ornamentation techniques, such as trills and mordents, were part of the performance style even in the Renaissance, although these would become more fully developed in Baroque music.

Ensemble Use:

The harpsichord was commonly used in soft ensembles (bas) in the Renaissance, often accompanying singers or playing continuo in chamber settings. It was often paired with viol, lute, or other softer instruments in consort performances.

A common Renaissance use was in the context of continuo—a bass line that would be filled out by the harpsichord, providing harmonic support to a vocal or instrumental line. The harpsichordist would improvise the harmonies based on the bass line.

Musical Example

Piece: "La Folia" (anonymous, late 16th century)

Instruments: Harpsichord, lute, and viol

Description: This piece is a famous variational form. The harpsichord plays a repeating bass line with variations, while other instruments add ornamentation and more complex variations on the theme.

Source: This piece is found in various Renaissance collections, such as the Chansonnier de Saint-Germain.

Conclusion

The harpsichord is an essential part of Renaissance music, often used for both solo performance and accompaniment in consorts. Its bright, plucked sound, combined with its use in continuo and harmonic accompaniment, allowed it to fulfill an important role in Renaissance musical practices. Though it lacks dynamic range compared to modern instruments, its clear articulation and variety of tonal colors make it highly adaptable in both private and public performances.

By exploring the construction, tuning, and performance techniques of the harpsichord, we gain a greater appreciation for its role in the Renaissance ensemble. The study of primary sources, including manuscripts and performances, is crucial for understanding the importance of this instrument and its influence on the evolution of Western music.

Secular Song of the 15th Century

The 15th century was a period of flourishing secular song in Europe, particularly in France and the Low Countries. Secular songs were written in vernacular languages (such as French, Italian, and English) and were typically performed by both professional and amateur musicians. These songs often followed certain musical forms and were often accompanied by instruments like the lute, viols, or organ.

A key feature of 15th-century secular music was the use of the forme fixe and related musical structures. These forms played a significant role in shaping the sound and structure of Renaissance chansons and other secular vocal music.

Forme Fixe

The forme fixe ("fixed form") refers to a specific, recurring pattern used in the construction of French secular chansons during the late Medieval and Early Renaissance periods. The most common forms under this label were the Rondeau, Ballade, and Virelai.

Rondeau:

Structure: The Rondeau consists of a refrain (a recurring musical section) alternating with verses (stanzas of text). The refrain returns after each verse, following a pattern of ABaAabAB (capital letters represent the refrain, and lowercase letters represent the verses). This form was very popular in the 15th century and often used in secular songs.

Example: Guillaume Dufay’s “De tous biens plaine” is a famous Rondeau.

Ballade:

Structure: The Ballade also uses repeated refrains, but its form is usually ababbC (where C is the refrain and the other letters represent the verses).

Example: Guillaume Dufay's “Se la face ay pale” can be seen as an example of this form, although it contains stylistic elements from the Renaissance motet as well.

Virelai:

Structure: The Virelai features a form where the refrain is repeated in a way similar to the Rondeau, but it has a more distinct melody in each repetition. This form is typically characterized by a AabC pattern, with the refrain (A) being followed by a contrasting stanza.

Notable Examples of 15th Century Secular Song

1. "De tous biens plaine" by Guillaume Dufay

Form: Rondeau

Composer: Guillaume Dufay (1397–1474), one of the most influential composers of the early Renaissance.

Context: This Rondeau is an example of Dufay's secular vocal music, set to a French text that expresses the themes of love and courtly emotions.

Analysis: The piece follows the forme fixe structure with an alternating refrain and stanzas. The refrain is repeated throughout, creating a sense of circularity and unity within the piece. The text and music express the feelings of the poet toward an idealized lady.

Musical Features: Dufay uses imitation, counterpoint, and homophonic textures in this piece, which is typical of his style. The music blends Medieval techniques with early Renaissance elements, especially in the harmonic language.

2. "Se la face ay pale" by Guillaume Dufay

Form: Ballade

Composer: Guillaume Dufay

Context: This famous Ballade was composed for the Duchess of Savoy, Marguerite de Clèves, and is a clear example of Dufay's mature style in the 15th century. The title translates to “If my face is pale,” which conveys themes of longing and courtly love.

Analysis: In this piece, Dufay employs the ballade form with repeated refrains and verses. The first stanza introduces the main idea of unrequited love, and the refrain functions as a way to repeat the central theme of the song. The piece showcases Dufay’s mastery of melodic construction, as well as his ability to create harmonically rich and expressive textures.

Musical Features: The harmonic movement is more sophisticated than earlier works, with the use of consonance and dissonance to evoke emotional nuances. The piece also features contrapuntal techniques and syncopation, which add complexity to the overall texture.

3. "Se la face ay pale" by Guillaume Dufay (cont’d)

This piece is especially notable for its sophisticated rhythmic structure. The lively rhythmic patterns are a departure from the static rhythms of earlier Medieval music and are a precursor to the more fluid rhythms of the Renaissance.

Odhecaton A

Odhecaton A is one of the earliest printed collections of music from the Renaissance, published in 1501 by Ottaviano Petrucci, a pioneering music printer in Venice. It features a collection of secular vocal music from Guillaume Dufay, Gilles Binchois, and other composers. The Odhecaton A was significant in spreading the new musical style of the early Renaissance through the print medium.

Notable Features: The collection features both polyphonic (many voices) and homophonic (same rhythm, different notes) textures, and it helped popularize the works of the Burgundian School composers such as Dufay and Binchois.

Gilles Binchois

Biography: Gilles Binchois (c. 1400–1460) was a Flemish composer and one of the leading figures of the Burgundian School in the early 15th century. His music is known for its smooth, flowing melodic lines, often paired with rich harmonies.

Contribution: Binchois composed mainly in the formes fixes (including Rondeaux and Ballades). His works were widely circulated during his time, and he was greatly admired by his contemporaries.

Example: Binchois's “De tous biens plaine” is a well-known example of the Rondeau form. Like Dufay’s works, Binchois's music reflects the emerging Renaissance style, which combined harmony, melody, and counterpoint in more complex ways than Medieval music.

Conclusion

The 15th century marked a key period in the development of secular song, particularly with the forme fixe and the Renaissance chanson. Composers like Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois helped shape the polyphonic chanson with their sophisticated use of form and counterpoint. Their works, preserved in important collections like Odhecaton A, demonstrate the transition from Medieval to Renaissance styles, with more complex harmonies and rhythmic fluidity that would influence music for generations.

The study of works such as “De tous biens plaine” and “Se la face ay pale” showcases the technical and emotional depth of 15th-century secular song, highlighting the role of composers in shaping the soundscape of the early Renaissance.

Notation, Proportion, and Tempo in Medieval and Renaissance Music

During the Medieval and Renaissance periods, music notation underwent significant developments, which allowed for greater precision in recording musical rhythms and a more systematic approach to interpreting tempo and proportion. These developments played a crucial role in shaping the performance of music during these periods.

1. The Basic Note Values: Long, Breve, Minim, Semiminim, etc.

In Medieval and Renaissance music, the note values used to notate rhythms were hierarchical. Each note value indicated how long a note was to be held relative to others:

Long (ℓ): The long was the longest note value and was subdivided into breves. In Medieval notation, the long was used in highly rhythmic, measured music and was the equivalent of four breves.

Breve (𝄴): The breve was shorter than the long and was the basic unit of time in Medieval and Renaissance music. It was subdivided into minims and represented a duple division of time in perfect meter.

Minim (𝅘𝅥𝅮): The minim is the next shortest note value and was commonly used in both Medieval and Renaissance music. It could be subdivided into semiminims.

Semiminim (𝅘𝅥𝅯): The semiminim is half the duration of a minim and was used frequently in later periods to indicate faster subdivisions of the beat.

In Mensural notation, a long could be divided into two breves, a breve into two minims, and so on, forming a hierarchical system that could accommodate complex rhythmic relationships.

2. Tempus (Perfectum and Imperfectum)

In Medieval and Renaissance notation, Tempus (Latin for “time”) referred to the unit of measure that defined the rhythm of a piece. There were two primary types of tempus:

Tempus Perfectum (Perfect Time):

Definition: This was a time signature where the beat was divided into three equal parts, often represented by a circle (𝌓) or triple meter.

Subdivision: The smallest unit in Tempus Perfectum was the semibreve, which could be divided into three minims (a pattern of 3:1).

Use: It was common in early Renaissance and Medieval music to use Tempus Perfectum to signify meter with triple subdivisions, which produced a "rolling" feel that reflected the perfect proportions.

Tempus Imperfectum (Imperfect Time):

Definition: Tempus Imperfectum was a time signature where the beat was divided into two equal parts, often represented by a semi-circle (𝄸) or duple meter.

Subdivision: The minim was the basic unit in Tempus Imperfectum, and it could be subdivided into two semiminims (a pattern of 2:1).

Use: Tempus Imperfectum was typically used in the later Renaissance and in certain forms of Gregorian chant, giving music a more regular, two-part feel.

3. Mensuration Signs

Mensuration signs were symbols used in Medieval and Renaissance music notation to indicate the meter and rhythmic subdivisions of a piece. The mensural system distinguished between perfect and imperfect proportions based on how the beats and subdivisions were organized. There were various symbols used to show different types of meters:

The Circle (𝌓): This indicated perfect time, meaning that each beat was divided into three.

The Semi-circle (𝄸): This indicated imperfect time, meaning that each beat was divided into two.

C (Common Time): The "C" symbol was used in both perfect and imperfect tempus, indicating a simple quadruple time, dividing each measure into four beats.

The Long and Breve Symbols: These symbols also helped determine the proportions of time in a given piece by indicating how long the basic units of time should last.

Mensuration signs were used in combination with proportions to create complex rhythms and meter changes throughout a composition.

4. Prolatio (Prolation)

Prolatio (or prolation) referred to the subdivision of time within Tempus. It described the way that each note value was subdivided into finer units of time.

Prolatio Major (Major Prolation): This signified that the semibreve was subdivided into three parts (as in perfect time). The symbol for prolation major was a circle with a dot in the center (𝌓).

Prolatio Minor (Minor Prolation): This indicated that the semibreve was subdivided into two parts (as in imperfect time). The symbol for prolation minor was a semi-circle (𝄸).

These proportional relationships were essential for composers to organize the rhythms within their pieces, particularly in polyphonic music, where multiple voices or parts would follow different rhythmic patterns at the same time.

5. Johannes Tinctoris

Johannes Tinctoris (c. 1435–1511) was a Flemish composer and theorist who played a significant role in codifying and systematizing music theory during the Renaissance.

Key Work: His most important work, "Liber de arte contrapuncti" (The Art of Counterpoint), was a musical treatise that explored the rules of counterpoint and harmony.

Influence: Tinctoris made important contributions to the understanding of rhythm, notation, and polyphony. He was instrumental in distinguishing between "good" and "bad" counterpoint and helped shape the emerging Renaissance style of music.

6. Tactus

Definition: Tactus refers to the steady, regular beat that serves as the foundation of a piece of music. The tactus was the physical gesture (often performed by the conductor or leader of the ensemble) that indicated the tempo or rhythmic pulse of the music.

Tempo Indicator: The conductor would often use their hand or a stick to show the tactus in time with the music. In a duple meter, the conductor would tap their hand twice per measure (representing two beats), while in triple meter, the hand would make three taps per measure.

Use: The tactus was an important tool for keeping tempo and was especially important for polyphonic music, where multiple voices or instruments had to stay in time with one another.

7. "Tempo Giusto"

Meaning: The phrase “tempo giusto” (Italian for “exact tempo”) is often used in modern music to indicate that the performer should play at the correct, unaltered speed, without rushing or slowing down.

In Renaissance music, the idea of maintaining an accurate and steady tempo was central to performance. While composers did not often specify exact tempos in the same way we do today, the tactus and mensural signs were the tools that performers used to maintain the intended pace of the music.

8. Proportions / Tempus / Tactus

Proportions: In the Renaissance, proportions indicated how long each note value lasted in relation to the other note values. For instance, perfect proportions meant that each unit of time was divided into three smaller units, while imperfect proportions divided time into two smaller units.

Tempus was a larger unit of measurement in which the music was organized, and tactus was the steady beat that helped keep everything in time. In more complex music, composers used mensuration signs and proportions to create intricate rhythmic patterns and polyphonic textures.

Conclusion

The system of notation, proportion, and tempo in Medieval and Renaissance music was essential for shaping the musical landscape of the time. From tempus perfectum and imperfectum to the development of mensural notation, composers and performers had sophisticated tools at their disposal to structure their music in a way that reflected both the precision of rhythm and the emotional content of the composition. Understanding tactus, prolatio, and the ideas of theorists like Johannes Tinctoris gives us deeper insight into how Renaissance music was interpreted and performed.

Differences Between Modern Notation and Original Renaissance Editions

1. Modern Notation vs. Renaissance Notation:

The system of musical notation in the Renaissance was different from our modern standardized notation in several key ways. Here are some important differences:

a. Shape and Structure of Notes:

Modern Notation: Modern notation uses a system of round note heads and stems attached to a notehead, making it very clear how long a note is meant to be held based on the note's shape (whole, half, quarter, etc.).

Renaissance Notation: Renaissance notation used different note shapes that often looked more angular or rectangular compared to modern notes. Notes like the long, breve, minim, and semiminim had different symbols and sometimes rectangular shapes. The note heads were also more variable, sometimes resembling squares or diamonds, especially in the early Renaissance.

b. Time Signatures and Mensuration:

Modern Notation: In modern notation, time signatures (such as 4/4, 3/4) are used to indicate the number of beats per measure and the value of the beats. The time signature is placed at the beginning of the piece or a section of music.

Renaissance Notation: In contrast, mensural notation was used in the Renaissance, which had its own system of mensuration signs (circle, semi-circle, C-shaped, etc.) to indicate time values. These signs could indicate whether the music was in perfect or imperfect time, and whether each beat was divided into two or three parts. There were no time signatures as we understand them today, and rhythm was indicated through the use of proportions and time signatures based on the specific type of music.

c. Rhythm and Proportions:

Modern Notation: Modern notation has standardized note values like quarter notes, eighth notes, and dotted rhythms, which are easily readable in terms of subdivisions (dividing the beat into consistent portions).

Renaissance Notation: Renaissance notation used proportions and mensural values that could create complex rhythmic patterns. A breve (the basic unit of time) could be subdivided into three minims (for perfect time) or two minims (for imperfect time). It was possible to have music with changing or varying rhythmic subdivisions throughout, and the notation system was more fluid in terms of how long notes lasted relative to others.

d. Clefs and Pitch Notation:

Modern Notation: Modern notation uses fixed pitch systems, and treble, bass, alto, and tenor clefs indicate specific notes (e.g., middle C).

Renaissance Notation: In the Renaissance, the use of clefs was more variable. There was no standardized pitch for the C clef or F clef, and depending on the clef used, the range of the voice or instrument could be notated differently. A piece could be transposed easily if you changed the clef, which made it more flexible but also more complex to read.

e. Accidentals:

Modern Notation: Accidentals (sharps, flats, naturals) are used extensively and apply to specific notes throughout a measure.

Renaissance Notation: Accidentals in Renaissance notation were indicated using letters or signs, but these could be notated differently from modern practices. Some early manuscripts did not use accidentals at all, assuming the performer would know when to apply them (especially in chant or modal music).

Sign of Congruence in Renaissance Notation:

The sign of congruence (often denoted as a symbol resembling an equals sign, or “≡”) was used in Renaissance music to show that two sections of music were to be performed similarly or were identical. This would indicate that a passage of music, such as a repeated section or a similar phrase, should be performed in the same way or in congruent (identical) fashion.

The symbol appeared primarily in the context of motets, masses, and other works that involved repetition of certain material. It helped performers understand that sections of music were related, avoiding the need to write out the same passage multiple times.

How Did They Keep Time in the Renaissance?

Keeping time in the Renaissance was a crucial aspect of performance, especially in polyphonic music where multiple voices had to stay in sync. Musicians in the Renaissance used various methods to help maintain a steady tempo and rhythm, which were somewhat different from modern methods.

1. Tactus (The Beat):

The most common method for keeping time was the tactus, a steady, regular beat that would be indicated by a conductor or leader of the ensemble. The tactus was often marked by hand gestures (like a beating of the hand or using a tuning fork).

Tempo was indicated using terms like "adagio" or "allegro," and the performer would follow the tactus to maintain the pulse of the music.

In a duple meter, the tactus might involve a hand moving in two beats per measure, while in triple meter, the hand would move in three beats per measure.

2. The Use of a Conductor:

Larger groups or choirs would often have a conductor who would use a steady beat (tactus) to guide all the performers.

In this case, the conductor would indicate the rhythmic pulse and ensure all musicians were aligned in the tempo and rhythm. This helped groups maintain consistency when performing polyphonic music, where multiple voices or instruments played different lines.

3. Use of the Mensuration Signs and Prolatio:

In more complex works, mensural notation indicated the proportions of the music, letting performers know how to subdivide their beats. These proportions were critical for keeping time during polyphonic music.

Musicians would be guided by the mensural notation to interpret how beats and note values were divided, and the conductor would help maintain the proper tactus in such cases.

4. Instruments and Tuning:

Percussion instruments such as drums or bells were sometimes used in ensembles to mark time, especially in outdoor settings or for large-scale performances.

Summary

Modern notation differs from Renaissance notation in the use of note shapes, time signatures, and clefs. Renaissance music notation was more flexible and relied on proportions and mensural signs to indicate rhythm.

The sign of congruence was used to indicate identical musical sections, aiding performers in reading repeated or similar sections.

Keeping time in the Renaissance was primarily done through the use of tactus, the conductor's gestures, and the careful interpretation of mensural notation. This system allowed performers to stay in sync during the complex polyphony of the time.

Renaissance Music Theory: Key Concepts

Renaissance music theory built on the foundations of medieval music theory while developing and refining concepts that influenced the practice of music during this period. Below are some of the key concepts, terms, and rules in Renaissance music theory.

1. Cadential Rules

In Renaissance music, cadences were essential for marking the end of musical phrases, sections, or entire works. Cadential rules governed how phrases ended, creating a sense of closure and resolution. The cadence typically resolved on a perfect consonance (unison, octave, or perfect fifth) and often involved harmonic progression.

Types of Cadences:

Authentic Cadence: The most common type of cadence, involving a progression from the dominant (V) chord to the tonic (I), like the modern V-I progression. In Renaissance music, this was typically approached by consonant intervals such as the fifth and octave.

Plagal Cadence: Known as the “Amen cadence”, this involves a progression from IV to I (e.g., C-F-C). It was used less frequently but still a recognizable feature in the Renaissance, especially in chant and motets.

Half Cadence: This is a cadence that ends on the dominant (V) chord, leaving the phrase or section unresolved, and often used to create a sense of suspense before moving to a final resolution.

Deceptive Cadence: This occurs when the V chord resolves to a different chord, typically the vi chord (a minor chord) rather than the tonic.

2. Musica Ficta Rules

Musica ficta (Latin for "false music") refers to the practice of adding accidentals (such as sharps or flats) to notes that were not originally written in the notation. These accidentals were used to improve the harmonic or melodic flow of a piece. The rules of musica ficta were based on a combination of theoretical principles and practical performance choices.

Guidelines:

Chromatic Alterations: In the Renaissance, singers or instrumentalists would raise a note by a half-step to avoid awkward intervals or harmonic dissonances. For example, if a B natural appeared in a C major scale, a B flat might be altered to B natural in order to lead smoothly to a C.

Avoiding Unpleasant Intervals: Musica ficta helped avoid awkward or dissonant intervals like augmented seconds and tritones in melodies and harmonies.

Cadences: Accidentals were frequently added at cadences to ensure that the harmony resolved cleanly, especially in the final chord of a phrase. For instance, a leading tone (the seventh note of the scale) would often be raised to resolve to the tonic in cadences.

3. Modes (Authentic and Plagal)

Modes in Renaissance music refer to specific scales or collections of pitches that define the melodic and harmonic structure of a piece. There are eight modes, each defined by its finalis (the tonic note) and range.

Authentic vs. Plagal Modes:

Authentic Modes: These modes are "full" modes that use the finalis as the lowest pitch of the scale. The authentic modes typically extend from the finalis up to the octave.

Dorian (D to D)

Phrygian (E to E)

Lydian (F to F)

Mixolydian (G to G)

Plagal Modes: These are "extended" modes that use the finalis as the highest note of the range, but the range goes below the finalis to the fourth scale degree.

Hypodorian (A to A)

Hypophrygian (B to B)

Hypolydian (C to C)

Hypomixolydian (D to D)

Authentic modes are used for melodies that start on the tonic, while plagal modes are used for melodies that begin on a note below the tonic. The choice of mode dictated how a melody was constructed, the kind of cadences that could occur, and how the harmonic structure was shaped.

4. Solmization

Solmization is the practice of assigning syllables to the notes of a scale to help singers remember and reproduce melodies. The syllables used in solmization during the Renaissance were derived from the hexachord system.

Syllables:

Ut (now Do)

Re

Mi

Fa

Sol

La

The syllables were assigned to hexachords (collections of six notes). The syllables allowed singers to easily recall and sing the steps of a melody.

Hexachordal System: The system was based on three hexachords: natural, hard, and soft, each having different starting notes and used in different contexts. The hexachord was essential for musical education during the Renaissance.

5. Hexachord (Natural, Hard, Soft)

A hexachord is a six-note scale used in the Renaissance, and each hexachord was based on a specific set of pitches and had unique characteristics depending on whether it was natural, hard, or soft.

Natural Hexachord: This hexachord consisted of the notes C-D-E-F-G-A and was the most common in Renaissance music. It was considered the "basic" hexachord.

Hard Hexachord: The hard hexachord used the notes G-A-B-C-D-E and was distinguished by the B natural (as opposed to B flat in the natural hexachord). It was used for more sharp-sounding or bright intervals.

Soft Hexachord: The soft hexachord used the notes F-G-A-B♭-C-D, where B flat was a characteristic of this hexachord. It was associated with a more mellow or flatter sound.

These hexachords allowed Renaissance musicians to use different scales to better fit different modal contexts and provided flexibility in melodic construction.

6. Guido’s Hand

Guido d'Arezzo (c. 991–1033) is credited with developing solmization and the guidonian hand, which was a system used for teaching and sight-singing in the Medieval and Renaissance periods. The guidonian hand was a mnemonic device in which each joint of the hand represented a note of the scale.

The thumb represented Ut (or Do in modern solmization), and subsequent fingers represented the other syllables (Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La).

The system allowed singers to visualize the pitches and the relationships between them while reading music, especially when sight-singing.

7. The Gamut

The gamut referred to the entire range of pitches available for use in Medieval and Renaissance music. The term came from the use of the Gamma (the Greek letter representing the lowest note in the system) and the ut syllable. The gamut was essentially the full set of pitches within the available modes.

Range: The gamut encompassed low to high notes, from Gamma (the lowest note) to the highest pitch used in composition.

It was used to describe the range of the modes and helped musicians understand the physical and theoretical boundaries of the music they were composing or performing.

8. "Extra Manum"

The term "extra manum" refers to notes that were outside the typical hexachordal system, often used for passing tones or auxiliary notes. These notes were not part of the typical hexachord but were allowed in some cases as decorative or melodic additions to the main scale.

These "extra" notes could be chromatic or altered notes, such as B♯ or C♯, and were often used in ornamentation or to create smooth melodic movement between the main scale tones.

Summary

Cadential rules in Renaissance music guided how phrases ended, often resolving on consonant intervals like the fifth or octave.

Musica ficta governed the use of accidentals in performance to improve the smoothness of harmony.

Modes (authentic and plagal) defined the scale and melodic rules for compositions.

Solmization and the hexachord system were essential for teaching and understanding melodies, with three types of hexachords: natural, hard, and soft.

Guido’s hand and the gamut were pedagogical tools to help musicians understand the full range of available notes.

"Extra manum" referred to notes that were added outside the normal range for expressive or ornamental purposes.

Renaissance Tuning and Temperaments: Key Concepts

Tuning and temperament were essential in shaping the way music was performed and heard during the Renaissance. In this period, various systems were used to divide the octave and adjust the relationship between pitches. These systems were not standardized as they are today, meaning tuning could vary greatly depending on location, time period, and the type of music being played.

Here’s an overview of some of the key tuning systems and concepts related to Renaissance tuning and temperaments:

1. Pythagorean Tuning

Pythagorean tuning is a system based on the perfect fifth (the interval between two notes that have a frequency ratio of 3:2). This system focuses primarily on consonant intervals and the harmonic relationships between them, particularly the fifth and fourth.

Strengths: The system is based on the harmonic series and offers perfect consonances for fifths and octaves.

Weaknesses: The major third (the interval between the first and third notes of a scale) is too wide (about 81:64) and can sound out of tune compared to the more consonant major thirds used in just intonation.

Example: In Pythagorean tuning, a C-G perfect fifth will be very pure, but a C-E major third will be noticeably off when compared to the modern equal-tempered system.

When and where used: Pythagorean tuning was used in Medieval and Renaissance periods, particularly for instruments like the organ, harpsichord, and viols. It was most common in the early Renaissance before the development of other temperaments.

2. Just Intonation

Just intonation is a tuning system where the frequencies of the notes are derived from simple whole-number ratios. In this system, intervals are tuned based on pure intervals (such as the perfect fifth, major third, and so on), which make the system more consonant.

Strengths: Just intonation produces highly pure intervals, and the intervals of thirds, fifths, and sixths sound particularly sweet and consonant.

Weaknesses: Just intonation becomes problematic when you need to play in multiple keys or modulate, because the system is based on a specific key or tonic. Changing keys in just intonation requires retuning the instruments.

Example: A C-G perfect fifth is 3:2, and a C-E major third is 5:4, both of which sound very consonant in just intonation.

When and where used: Just intonation was often used in vocal music, particularly in polyphonic settings where each voice or part could stay within a single key, allowing the system to be employed effectively.

3. ¼ Comma Meantone

The ¼ comma meantone temperament is a compromise tuning system that slightly adjusts the intervals between pitches so that the major thirds are pure, but the fifths are slightly flattened. The system is designed to make major thirds sound consonant, but it sacrifices the purity of the perfect fifths.

Strengths: The system provides very consonant major thirds (such as C-E, which is about 5:4) and usable tuning for the major keys.

Weaknesses: The fifths are slightly out of tune, and this system can sound dissonant in minor keys. Additionally, playing in keys far from the home key becomes problematic as the tuning system doesn't allow for a perfect fifth across all keys.

Example: In a ¼ comma meantone system, the C-G fifth will not be perfectly pure, but the C-E major third will be much more consonant than in Pythagorean tuning.

When and where used: The ¼ comma meantone system was widely used during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, particularly for keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord and clavichord, which required a compromise between consonance and practicality.

4. Flexible Instruments vs. Inflexible Instruments

Flexible Instruments: These instruments are able to alter their pitch during performance. For example:

String instruments (like the violin or lute) can be easily retuned or adjusted to match the tuning system being used.

Wind instruments (like the recorder or shawm) can adjust pitch by altering their fingerings or the way they blow into the instrument.

Inflexible Instruments: These instruments have a fixed pitch, which limits their ability to adjust their tuning. For example:

Keyboard instruments (like the organ, harpsichord, and clavichord) cannot easily adjust their tuning once they are tuned, making them more challenging to adapt to different temperaments.

Brass instruments (like the trumpet or sackbut) typically have limited capacity to adjust pitch.

5. Major and Minor Semitones

Major Semitone: This refers to the larger semitone (also known as the whole tone minus one semitone). In just intonation or Pythagorean tuning, the major semitone has a frequency ratio that is larger than the minor semitone, often leading to a sharper, more dissonant sound when compared to modern equal temperament.

Minor Semitone: The smaller semitone, often referred to as a half step. In many historical tunings, this would refer to the difference between two pitches that are a half step apart but with different ratios. In Pythagorean tuning, for instance, the minor semitone may be slightly sharper than in modern tuning.

6. Chorton (Choir Pitch) and Kammerton (Chamber Pitch)

Chorton (Choir Pitch): This was a lower pitch standard used primarily for vocal music (especially for choirs) in the Renaissance. Chorton was set lower to ensure the singers could maintain vocal health and produce sound that was not too straining for the voice.

Kammerton (Chamber Pitch): This was a higher pitch standard used for instrumental music, particularly in chamber music or secular instrumental ensembles. Kammerton allowed for a brighter and more resonant sound on instruments and was often a little higher than the Chorton pitch.

When and Where Were These Systems Used?

Pythagorean Tuning: Primarily used in the Medieval period and through the early Renaissance, especially in vocal music and organs.

Just Intonation: Used in vocal music and choir singing, particularly when a fixed key could be maintained. It was sometimes used for early keyboard instruments like the clavichord.

¼ Comma Meantone: Used from the late Renaissance into the Baroque period, especially in keyboard instruments and consorts. It was popular in regions such as Italy, Germany, and parts of England.

Chorton and Kammerton: These pitch standards were more regional and were used in different areas and contexts. Chorton was more commonly associated with choir music, while Kammerton was used in instrumental settings.

In-Depth Study of a Renaissance Tuning System: Just Intonation

Introduction:

Just intonation is a tuning system based on the natural harmonic series, where intervals are derived from simple whole-number ratios. Unlike equal temperament (which divides the octave into 12 equal semitones), just intonation tunes the intervals so that they sound "pure" and consonant according to the harmonic series. During the Renaissance, just intonation was commonly used in vocal music, early keyboard music, and instrumental music, especially in polyphonic and modal contexts.

This system offers a beautiful purity of sound for major thirds, perfect fifths, and other consonant intervals, but it can also have limitations, particularly when it comes to modulating to distant keys or using instruments with fixed tuning.

Strengths of Just Intonation:

Perfect Consonances:

Major thirds, perfect fifths, and octaves are particularly consonant in just intonation because the ratios are based on the harmonic series.

Perfect fifth (C-G) has a simple ratio of 3:2.

Major third (C-E) has a ratio of 5:4.

Octave (C-C) has a ratio of 2:1.

These intervals are perceived as very stable and harmonically "pure" because they are derived from the natural overtone series.

Aesthetic Appeal:

The sonority of just intonation, especially in a cappella vocal ensembles or small instrumental groups, is perceived as rich and full. The system allows for exceptionally consonant harmonies and produces sweet-sounding intervals that modern equal temperament struggles to achieve, particularly for the major third.

Expressive Potential:

Just intonation allows composers and performers to explore a range of expressive nuances because of the purity of its intervals. A choral group singing in just intonation will experience a natural blending of voices, with overtones aligning, creating a more harmonious sound than what would be possible with the slightly adjusted intervals of equal temperament.

Weaknesses of Just Intonation:

Limited Flexibility in Modulation:

Just intonation works beautifully in a single key, but it becomes problematic when attempting to modulate to distant keys. As the system is based on a specific tonic (such as C), when the key changes, the pitches of the thirds and fifths may no longer align well with the harmonic series.

For example, C-G will sound a pure fifth in the key of C, but when modulating to G major, the third (C-E) will sound out of tune because of the tuning differences.

This lack of tuning flexibility was one of the reasons why temperament systems like quarter-comma meantone and eventually equal temperament were developed in the later Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Incompatibility with Fixed-Pitch Instruments:

Instruments such as the harpsichord, organ, and clavichord have fixed pitches, meaning they cannot adjust to different key centers. Because just intonation requires retuning to maintain the purity of intervals when changing keys, it is difficult to use on these instruments in polyphonic or modulating music. This limitation became apparent during the Renaissance when keyboard music began to be more complex.

Dissonance in Some Intervals:

While many intervals in just intonation are consonant, minor thirds and sixths can sometimes be less consonant than their modern equal-tempered counterparts. For example, the minor third (C-E♭) in just intonation has a ratio of 6:5, which is slightly flatter than the minor third in equal temperament. To the modern ear, this can sound somewhat "odd," and it can disrupt the overall balance of harmony in a piece.

Just Intonation in Practice:

Vocal Music:

Choral music of the Renaissance, especially in polyphonic works, often employed just intonation because of its ability to produce sweet, consonant harmonies. In an a cappella choral setting, singers could adjust to produce a more harmonious blend by aligning to the natural overtone series, with intervals like the major third and perfect fifth sounding pure.

For example, in Guillaume Dufay’s works, such as "Ave Regina Caelorum", the thirds and fifths between voices are consonant because the singers would tune their parts to each other, implicitly using a just intonation system.

Early Keyboard Music:

Early keyboard instruments like the clavichord or harpsichord could employ just intonation when playing in a single key. For instance, the clavichord could be tuned to a specific tonic key for a composition, ensuring the harmonic intervals sounded consonant. However, changing keys (modulating) or playing polyphonic music with distant tonalities would expose the system’s limitations.

Girolamo Cavazzoni, a Renaissance keyboard composer, would have composed pieces that were most effective in one key because the instruments tuned to just intonation could not easily modulate to other keys without causing dissonance.

Instrumental Music:

Instruments such as the lute and viola da gamba, which could be retuned or adjusted during performance, were able to make use of just intonation by tuning each string to achieve the purest intervals for the current key. When a lute player was performing a piece in C major, the instrument could be tuned so that the major third (C-E) would sound pure.

This flexibility allowed for an expressive range of intervals and harmonies not possible on instruments with fixed tuning, such as the organ or harpsichord.

Historical Context and Use in the Renaissance:

During the Renaissance, just intonation was widespread in vocal and instrumental music, especially in a time when composers were still largely working within modal systems. The modes themselves, with their specific tonic and dominant relationships, aligned well with just intonation’s ability to produce pure consonances.

For example, Josquin des Prez, one of the leading composers of the Renaissance, likely used a version of just intonation in his choral compositions, where the purer intervals of thirds and fifths would have been particularly important for the smoothness and clarity of his polyphonic style.

Example:

An example of just intonation in practice can be seen in "Sicut Cervus" by Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, a composer known for his smooth polyphonic choral writing. In this work, the harmonies of the upper voices blend naturally because the singers, adjusting to each other’s pitch, would be tuning their voices to pure intervals (such as the major third 5:4 and perfect fifth 3:2). This purity would create a rich, harmonious sound and enhance the overall clarity of the choral texture.

Conclusion:

Just intonation was a key tuning system used throughout the Renaissance, particularly in vocal and instrumental music. Its strengths lie in its ability to produce highly consonant and pure intervals, especially major thirds, perfect fifths, and octaves. However, its inflexibility in modulation and limitations with fixed-pitch instruments eventually led to the development of temperaments like mean-tone and equal temperament, which could accommodate the increasingly complex musical structures of the Baroque and Classical periods.

Despite its limitations, just intonation remains an important system in the history of music, offering a sweetness of sound and a harmonically rich texture that is appreciated by musicians, especially in a cappella choral settings or on flexible instruments.

ESSAY FORMAT

An In-Depth Study of Just Intonation in Renaissance Music

Just intonation is a tuning system rooted in the harmonic series, where intervals are based on simple whole-number ratios, such as the perfect fifth (3:2) or the major third (5:4). Unlike modern equal temperament, which divides the octave into twelve equal semitones, just intonation aims to achieve pure consonances by tuning intervals according to the natural overtones of a pitch. This tuning system was widely used during the Renaissance, especially in vocal music, early keyboard music, and instrumental performances. While just intonation offers beautiful harmonic clarity and purity, it also presents challenges when modulating between keys or adapting to instruments with fixed pitches. Despite these limitations, just intonation remains a vital part of Renaissance music history, providing a unique approach to tuning that shaped the aesthetic of the period.

Strengths of Just Intonation

One of the most significant advantages of just intonation is its ability to produce perfect consonances, particularly for intervals such as the major third, perfect fifth, and octave. In just intonation, these intervals are derived from the harmonic series, resulting in pitches that sound pure to the human ear. For example, the ratio of a perfect fifth is 3:2, and the ratio of a major third is 5:4. These intervals have been described as particularly stable and pleasing to the ear, creating harmonies that are consonant and rich in sound. The use of these pure intervals is a defining feature of the Renaissance sound, especially in polyphonic vocal music.

In addition to producing rich consonances, just intonation allows for a highly expressive performance. In vocal music, for example, choirs can adjust their pitch to align perfectly with one another, achieving a smooth and blended sound. The voices naturally adjust to the harmonics in the overtone series, resulting in a warm, cohesive blend that is difficult to replicate in systems like equal temperament. This is particularly evident in a cappella choral music, where singers tune their parts to achieve harmonically pure intervals, enhancing the overall sonic experience.

For instrumental music, just intonation offers similar benefits. Instruments like the lute, viola da gamba, and clavichord—which can be retuned during performance—benefit from just intonation because performers can tune their instruments to achieve the most consonant intervals for the piece at hand. This flexibility allowed instrumentalists in the Renaissance to experiment with different harmonic possibilities and create music that was sonically pleasing and expressive.

Weaknesses of Just Intonation

Despite its many advantages, just intonation also has notable weaknesses, particularly when it comes to modulation and fixed-pitch instruments. One of the most significant limitations of just intonation is its inability to accommodate easy modulation between keys. In just intonation, intervals like the major third and perfect fifth are tuned based on a specific tonic. As a result, when the key of a piece changes, the intervals may no longer sound consonant. For example, if a piece is in C major and modulates to G major, the C-G interval will no longer be as pure, and the C-E third will sound dissonant compared to the pure major third of the starting key. As music became increasingly complex in the late Renaissance and early Baroque periods, composers began to explore more flexible tuning systems that allowed for modulation to distant keys without the risk of dissonance.

Another weakness of just intonation is its incompatibility with instruments that have fixed tuning. Instruments such as the harpsichord, organ, and clavichord cannot easily adjust to the key changes required in more complex compositions. While vocal ensembles or stringed instruments could adjust pitch to ensure harmonic purity, keyboard instruments were fixed in their tuning once set. This made just intonation less practical for complex polyphonic works and led to the development of other tuning systems like quarter-comma meantone and equal temperament, which could accommodate the requirements of changing keys while still preserving some degree of consonance.

Additionally, while many intervals in just intonation are pure, others can sound slightly out of tune when compared to modern equal temperament. For example, the minor third (C-E♭) in just intonation has a ratio of 6:5, which is slightly flatter than the modern equal-tempered minor third. This can lead to the occasional dissonance or imbalance in harmony, particularly in more complex compositions.

Just Intonation in Practice

During the Renaissance, vocal music was one of the primary contexts in which just intonation flourished. Polyphonic choral works, in particular, were often performed using this tuning system. In works like Josquin des Prez's "Ave Maria" or Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina’s "Sicut Cervus," the harmonies are characterized by the use of pure intervals, and the voices are able to adjust their pitch to maintain consonance throughout the piece. This allowed for a rich, cohesive choral texture where the harmonic relationships between the voices were not marred by the subtle tuning differences found in later temperaments.

In terms of instrumental music, the lute and viol were particularly well-suited to just intonation. Both of these instruments could be re-tuned during performance, allowing for the adjustment of intervals as needed. The lute in particular, with its ability to be retuned for different pieces, could easily accommodate just intonation and produce the pure harmonies that were so desirable in Renaissance music. However, this flexibility was limited by the instruments with fixed tuning systems, such as the harpsichord, which could not easily adapt to the changing key centers that became more prevalent as music evolved.

Historical Context and Use in the Renaissance

Just intonation was in widespread use throughout the Renaissance, especially in the context of vocal polyphony. The Renaissance period was characterized by an emphasis on modal music, which lent itself well to just intonation. The modes of the time, such as Dorian, Phrygian, and Mixolydian, were based on a single tonic and often used consonant intervals within their respective scales. This made just intonation a natural choice for composers working within these modal systems.

In the works of composers such as Guillaume Dufay and John Dunstable, the harmonies are rich with perfect fifths and major thirds, demonstrating the preference for pure intervals that just intonation provided. The medieval and early Renaissance choirs and instrumental ensembles likely relied on just intonation to maintain the consonance and clarity of their sound.

Conclusion

Just intonation played a crucial role in shaping the sound of Renaissance music, offering purity and consonance that was particularly suited to the polyphonic choral music and instrumental pieces of the period. The system’s ability to produce rich harmonies made it ideal for the more homophonic textures of vocal music and the flexible nature of stringed instruments like the lute and viola da gamba. However, the system’s limitations in modulation and its incompatibility with fixed-pitch instruments such as the harpsichord and organ led to the eventual rise of more flexible tuning systems in later periods.

While just intonation eventually gave way to temperament systems that offered greater flexibility and ease of modulation, it remains an important aspect of Renaissance music theory and performance practice. Its ability to produce pure intervals and create harmonically rich textures continues to be appreciated by musicians and scholars today, providing a glimpse into the aesthetic and harmonic ideals of the Renaissance.

Knowt

Knowt