AN SCI 320 FINAL

Defining Health and Disease - 01/25/24

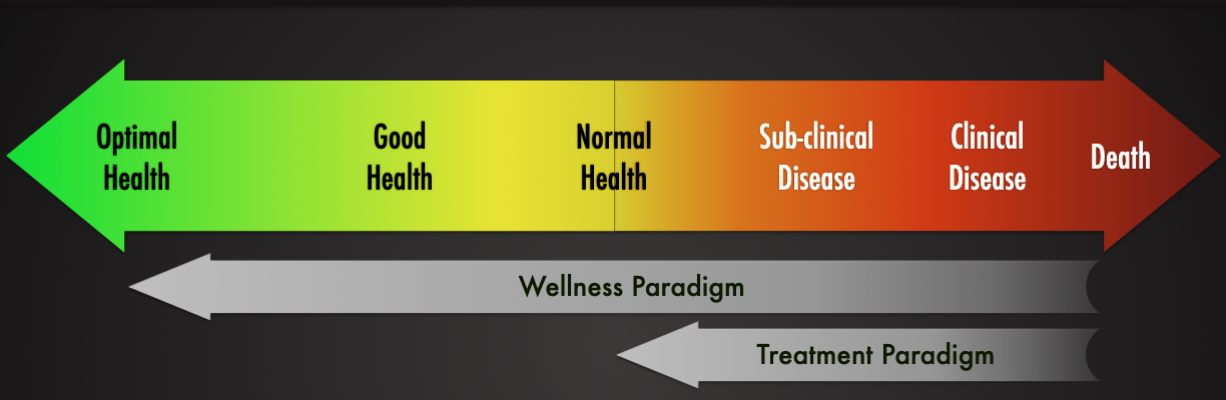

Health: a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

DIsease: condition of living animal or plant body or of one its parts that impairs normal function, and is typically manifested by distinguishing signs and symptoms.

Defining “disease” is pretty hard

Disease is relative to what people consider “normal”

Can be subjective: “one person's diarrhea is another person normal day

Some believe that our use of “health” and “disease” reflect value judgments

The definition can change with time as our knowledge evolves

Illness: a person's subjective experience of their symptoms. What the patient brings to their health care provider

Disease: underlying pathology: biologically defined: the healthcare provider’s perspectives

Sickness: social and cultural conception of this condition: cultural beliefs and reactions such as fear or rejection. These affect how the patient reacts.

Naturalism

Most prominent philosophical approach to defining health and disease

Reference Class: a natural class of organisms of uniform functional design: specifically, an age group or a sex of species

Normal Function: part or process within members of the reference class is a statistically typical contribution by it to their individual survival and reproduction

Disease: type of internal state which is either an impairment of normal functional ability

Health: the absence of disease

Criticisms:

Neglects the role values play in determining healthy or diseased

Provide definitions that rely exclusively on info from the biological sciences, but, lacks a basis in biological theory

Normativism

Disease is deviancy from some alternative state of affairs which is considered more desirable

Suggest that we both la people and medical professionals, should use health and disease in ways that reflect our values

Physiological or psychological states that we desire are called healthy and those we want to avoid are labeled diseases

Criticisms

Cases where we agree that a state is undesirable but we disagree over whether it is a diseased state (ex. Overweightness, PMS)

Values can change

Hybrid Theories

A condition is a disorder if and only if (a) the condition causes some harm or deprivation of benefit to the person as judged by the standards of the person’s culture (the value criterion), and (b) the condition results in the inability of some internal mechanism to perform its natural function, wherein natural function is an effect that is part of the evolutionary explanation of the existence and structure of the mechanism (the explanatory criterion)”

The term disease should only apply to dis-valued states with the proper biological etiology

Criticism

A state where there is no evolutionary dysfunction yet we disvalue that state

What influences the balance between health and disease?

Is aging a disease?

Colonization vs Infection - 01.30.24

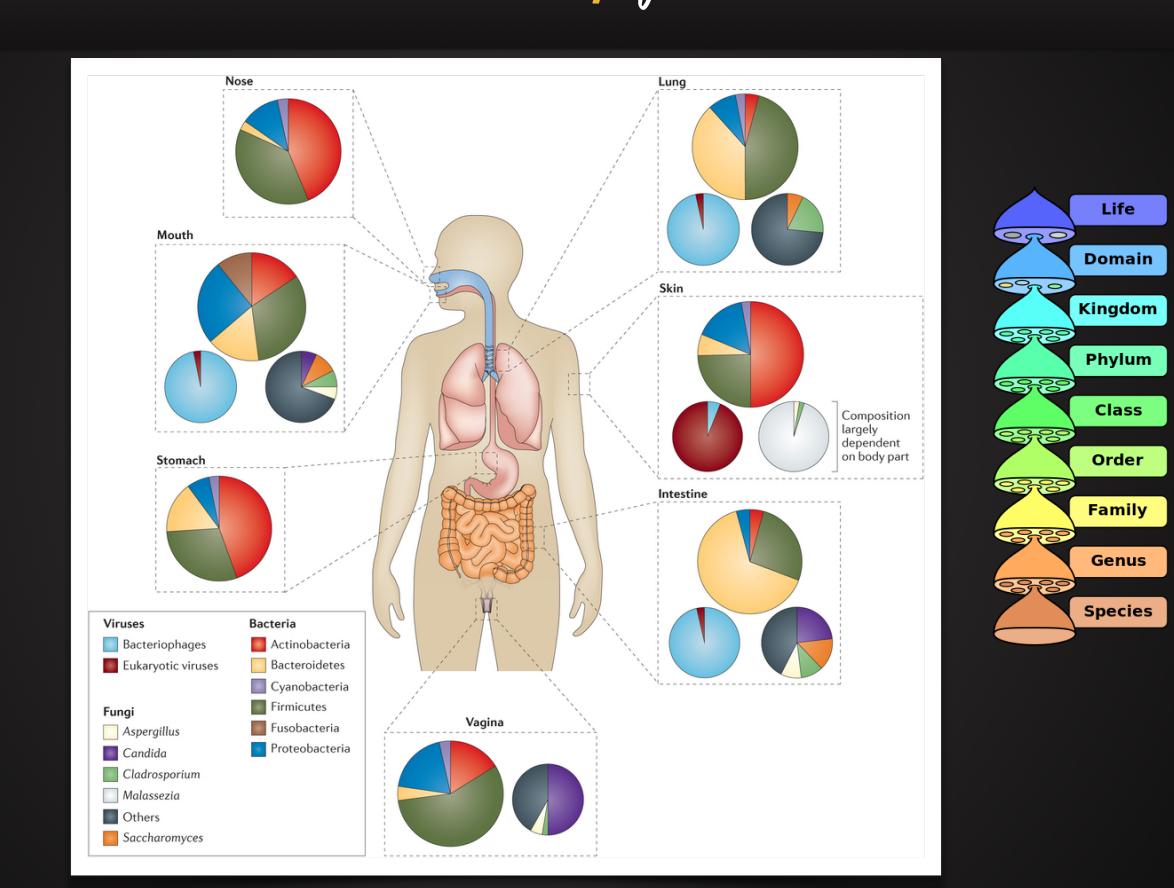

Colonization (normal flora)

Colonizing cells = 39 trillion

Normal Flora

Most areas of the body in contact with the outside environment harbor resident microbes

Microorganisms that normally reside at a given site and under normal circumstances do not cause disease

Normal flora is essential for health: (a) create an environment that may prevent infections and (b) enhance host immune defenses

Internal organs, tissues and fluids are microbe-free (relatively)

Transient flora

Occupy the body for only short periods

Usually picked up during daily activities (hand-shake, touch a door-knob, kissing)

Often eliminated easily (hand-washing)

Resident flora

Are permanently established (or for long periods of time)

Types of Relationships with Microbiome

Mutualism

Both the host and the microbe benefit

Examples: ruminants and their gut microorganisms (2) E. coli-microbe receives nutrients, but produces vitamins K and B- complex

Commensalism

One partner benefits, and the other neither benefits or is harmed

Parasitism

One organism benefits at the expense of the host

Cost to the host can vary from slight to fatal

An external parasite (flea, ectoparasite) is said to cause infestation

An internal parasite (endoparasite, tapeworm) is said to cause infection

Pathogenic

Organism causes damage to the hose during infection

Distribution and Diversity of Colonization

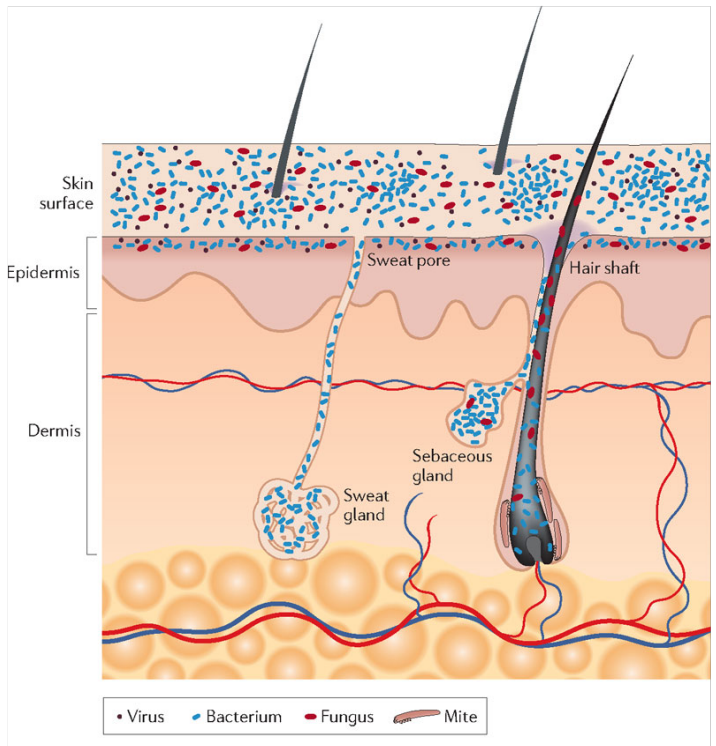

Microbial Colonization of the skin

Initial Colonization

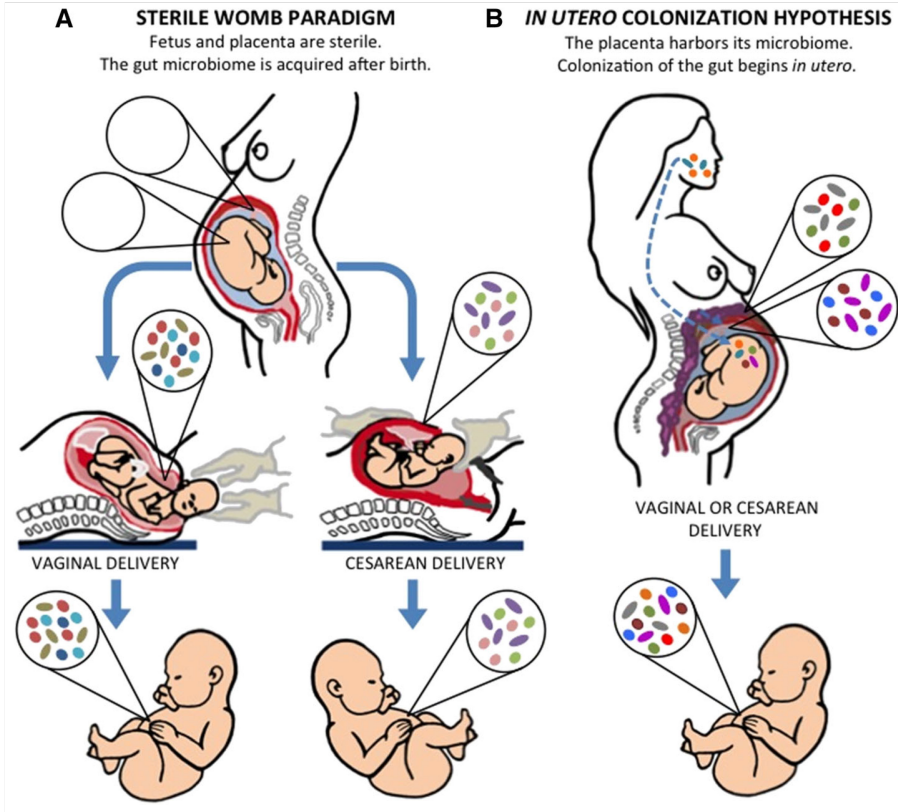

Prevailing paradigm

Uterus and contents are normally sterile and remain so until just before birth

Breaking of fetal membrane exposes the infant: all subsequent handling and feeding continue to introduce what will be normal flora

Is this paradigm entirely correct? → currently a controversial topic

Factors that influence Initial Colonization

Maternal factors

Gut microbiota

Vaginal health

Periodontal disease (other infections)

Genetics, diet, antibiotics

Birth

Vaginal vs. Cesarean delivery

Postnatal Factors

Genetics

Breastfeeding vs formula milk

Medications and antibiotics

Diet

Environment

Defining Infection

Infectious agent: viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, worms and prions

Infection: condition in which infectious agent penetrates host defenses

Infectious disease: an infection that causes damage or disruption to tissues and organs and/or physiological homeostasis

Endogenous infections

Occurs when normal flora is introduced to a site that was previously sterile (epidermis infection of wound)

Exogenous infections

Caused by organisms that are normally present in the body, but have gained entrance from the environment (influenza virus infection and respiratory tract)

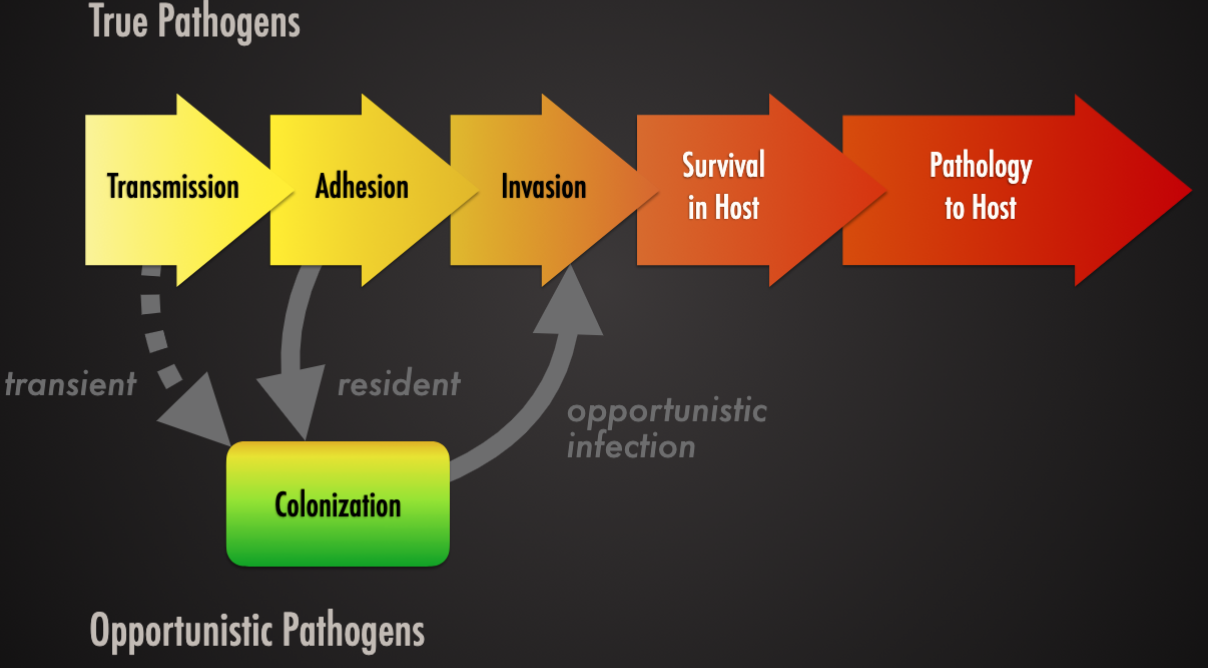

Types of pathogen

True pathogen (influenza virus): infectious agent that causes disease in virtually any susceptible host

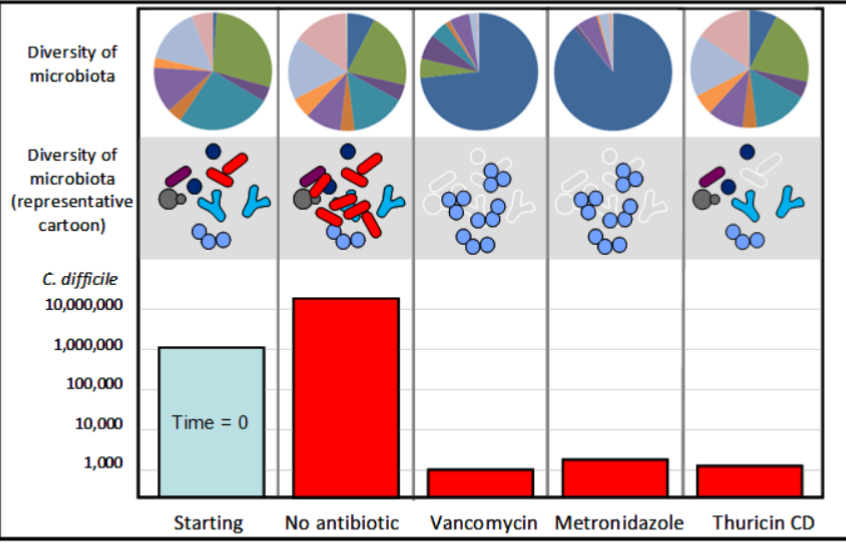

Opportunistic pathogen (pseudomonas, candida albicans): normally harmless: causes disease when the normal flora is disrupted (by antibiotics) or when the host is immunocompromised ( by drugs or other illnesses ).

Patterns of Infection

Localized infection: infectious agent enter the body and remains confined to a specific issue

Systemic infection: infection spreads to several sites and tissue fluids usually the bloodstream

Focal infection: infectious agent breaks loose for a local infection and is carried to other tissues

Mixed infection: several microbes grow simultaneously at the infection site (poly microbial)

Primary infection: refers to the first time you are exposed to (and infected by) a specific pathogen (UTI)

Secondary infection: another infection by a different microbe succeeding a primary infectionAcute Infection: comes rapidly, with severe but short-lived effects

Chronic (persistent) infection: progresses and persists over a long period of time

Infections that go unnoticed

Asymptomatic (subclinical) infections: although infected, the host does not show any signs of disease

Inapparent infection, so the individual does not seek medical attention

Ex. typhoid, chlamydia, HIV-1, epstein-Barr virus, Gonorrhoea

Mary Mallon, “Typhoid Mary” (1869 – 1938)

First person in the United States identified as an asymptomatic carrier of Salmonella Typhi (typhoid fever).

She was presumed to have infected 51 people, three of whom died, over the course of her career as a cook.

She was twice forcibly isolated by public health authorities and died after a total of nearly three decades in isolation

Acquisitions and Transmission of infectious agent

Communicable infection

Infected host an transmit the infectious agent to another host

Highly communicable infection is contagious

Non-communicable infection

Infection does not arise through transmission from host to host

Occurs primarily when a composed person is invaded by his/her own normal flora

Contracted organism from natural, non-living reservoir

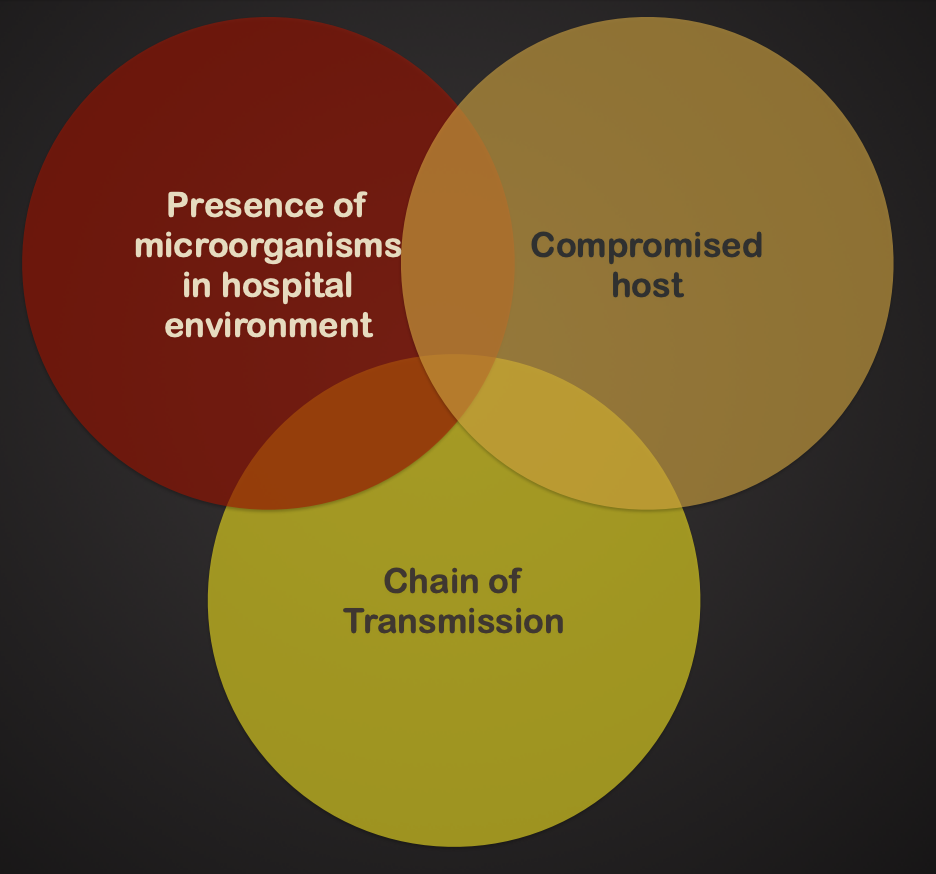

Nosocomial Infections

Infections acquired or developed during a hospital stay.

From surgical procedures, equipment, personnel, and exposure to drug-resistant microorganisms

2-4 million human cases/year in the US. 90,000 deaths. Impact in veterinary medicine not well studied.

What defines a particular disease?

Signs: (objective evidence)

Something that can be detected/measured by someone else (tachycardia, petechiae)

Symptoms: (subjective evidence)

Something that must be described by the one suffering the disease (anxiety, pain, fatigue)

Syndrome: the complete set of signs and symptoms associated with a specific disease (metabolic syndrome)

Introduction to Epidemiology 02.01.24

Roots of Epidemiology

Epidemiology is a fundamental science of public health.

Epidemiology has made major contributions to improving population health.

Epidemiology is essential to the process of identifying and mapping emerging diseases.

There is often a frustrating delay between acquiring epidemiological evidence and applying this evidence to health policy.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The study and analysis of the patterns (frequency and distribution) causes and effects of disease and health -related factors in populations

Epi “on, upon, befall”

Demo “people”

-ology - study of

Epidemiology: the study of which befalls people

Cornerstone of public health: shapes policy decisions and evidence-based practice

Major areas of epidemiological study include

Disease etiology

Transmission

Outbreak investigation

Disease surveillance and screening

Forensic epidemiology and screening

Biomonitoring

Comparison of prevention/treatment outcomes

Epidemiologist rely on:

Scientific disciplines to better understand disease

Statistics for efficient use of data and draw appropriate conclusions

Social sciences to better understand proximate and distal causes

Other fields for exposure assessment

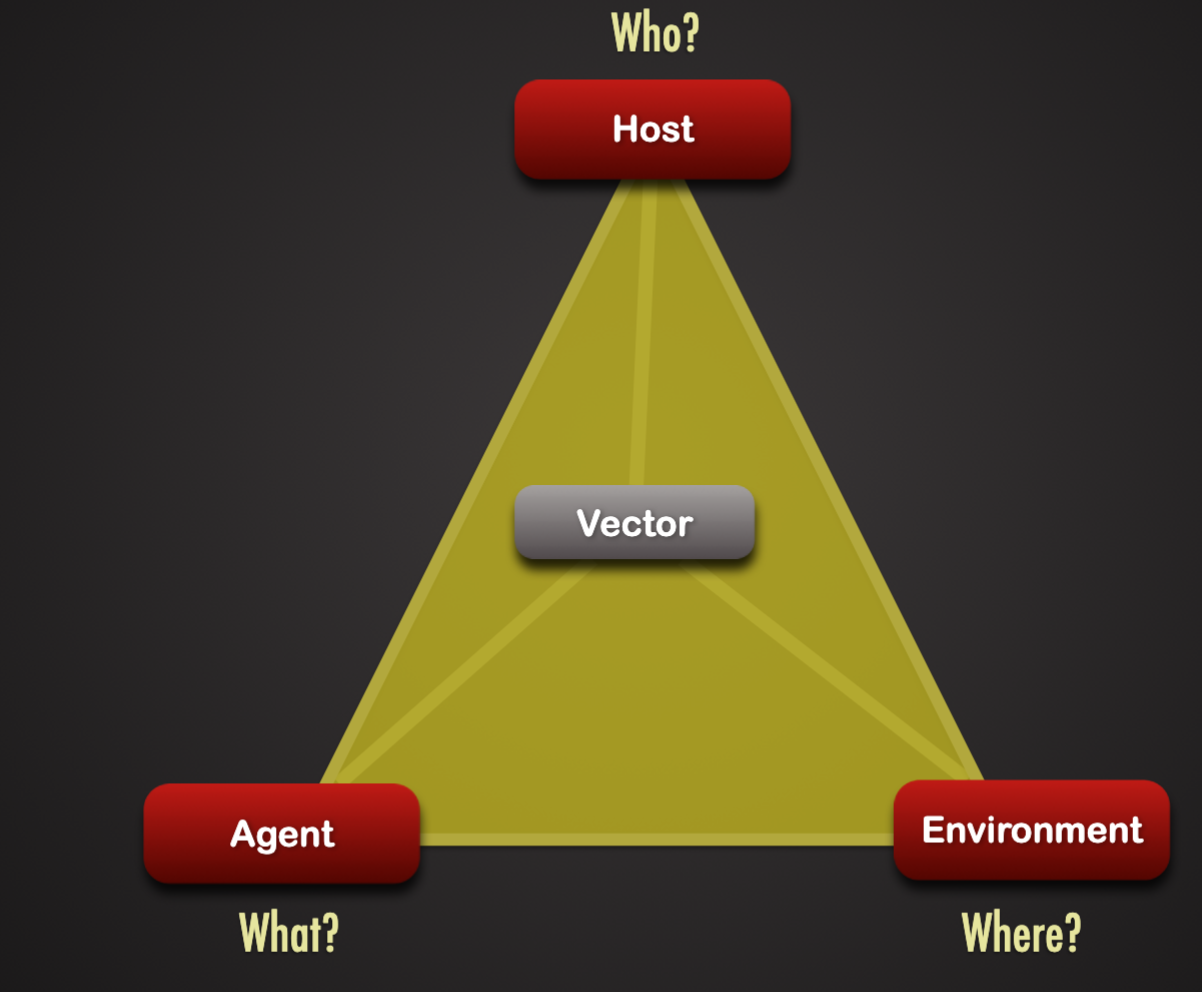

Host:

Immunity

General health

Age

Gender

Genetic background

religious/cultural practices

Agent

Pathogen traits

Virulence

Dose

Incubation period

Environment

Heat or cold stress

Food availability

Hygiene

Crowding

Cultural practices

Presence of vectors or reservoirs for pathogen

Pathogen Traits

Types:

Viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, worms and prions

Other information (strain, serotypes, etc, ex. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium)

Virulence

Ability to cause severe disease

Virulence factors: specific mechanisms that allow pathogen to adhere to or penetrate host cell, thwart immune defenses, damage host

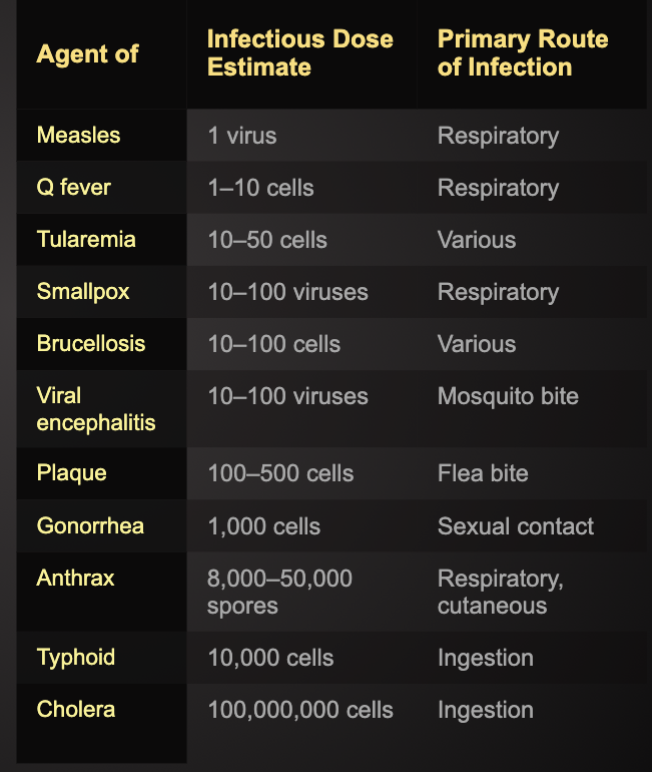

Infectious dose:

Minimum number of pathogens required to cause illness

Incubation period:

Time it takes after first exposure for the pathogen to cause signs and symptoms: influences extent of spread

Virulence: Infectious Dose (ID)

Minimum number of microbes required to cause infection in the host

Smaller the ID, the greater virulence

If ID is not reached, infection will not occur

ID50 (median infectious dose): amount of pathogenic microorganism that will produce demonstrable infection in 50% of exposed hosts

Host Traits

Immunity to pathogen

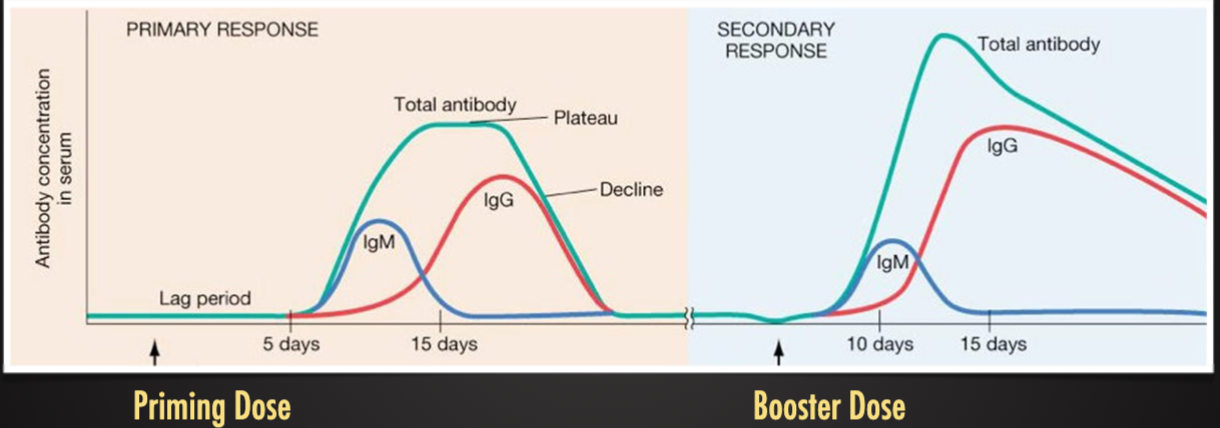

Previous exposure, immunization

Antigenic variation of pathogen can overcome

General Health

malnutrition , overcrowding, fatigue

Developing wor;d more susceptible: crowding, poor nutrition poor sanitation

Age

Very young, elderly generally more susceptible

Immune system less developed in young: wanes in old

Elderly also less likely to update immunizations

Genetic background

Natural immunity varies widely

Specific receptors critical for infection may differ in individuals (african swine fever: domestic pigs s warthogs)

Sickle cell gene and resistance to malaria

Gender

Females more likely to develop urinary tract infections

Urethra is shorter: microbes more likely to ascend

Pregnant animals are at more risks

Pregnant animals can pass on some disease to offspring

Religious and cultural practices

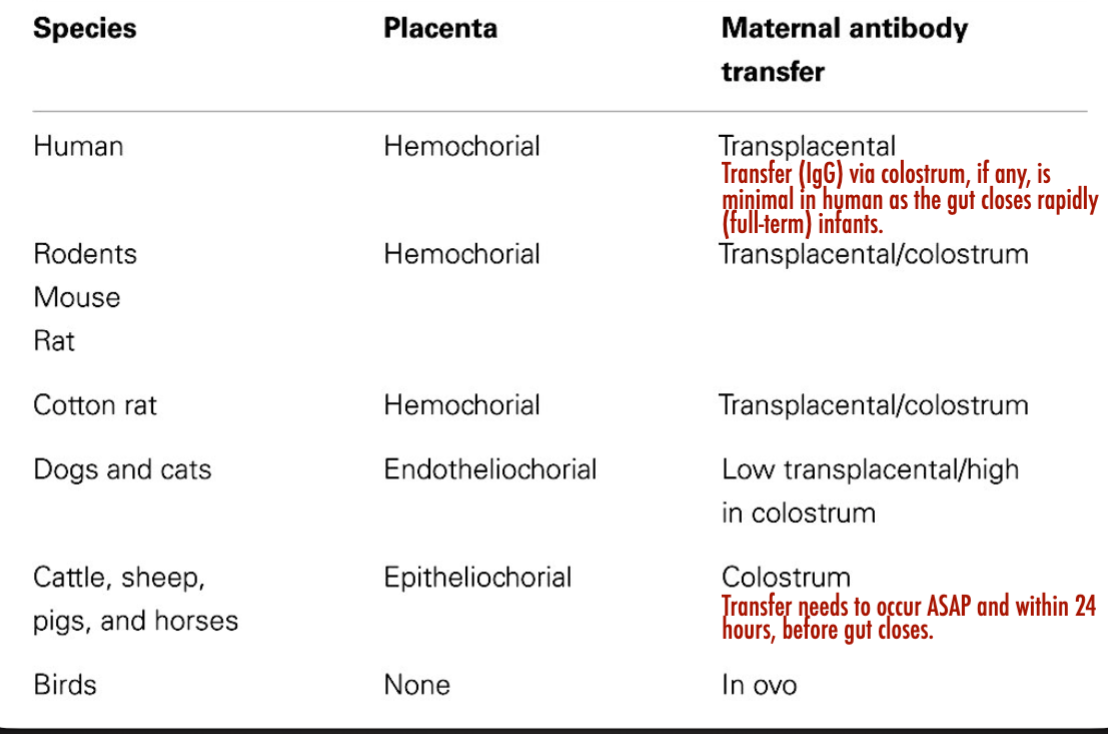

Breastfeeding provides protective antibodies to infants

Consumption of raw fish can increase exposure (ex. Freshwater fish and tapeworm Diphyllobothrium latum).

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors may increase likelihood of disease transmission opportunities or lower the hosts resistance to infection

Heat or cold stress

Food availability

Hygiene

Crowding

Cultural practices

Presence of vectors or reservoirs for pathogen

Routes of Transmission

Direct contact: physical contact or fine aerosol droplets

Some pathogens cannot survive in environment

Hand washing considered single most important measure for preventing spread of infectious disease

Horizontal vs vertical transmission

Indirect contact: passes from infected host to intermediate conveyor and the to another host

Some pathogens can survive for a period outside of the host

Fomite: inanimate object that serves a role in disease transmission (pens, cups, doorknobs, clothing, boots, etc)

Vector: any agent (insect, animal, or microorganism) that carries a pathogen and transmits it (mechanical or biologically) to human or animal hosts

Vehicle: typically food, water, or air (droplet nuclei, aerosols) that transmits a pathogen to the host

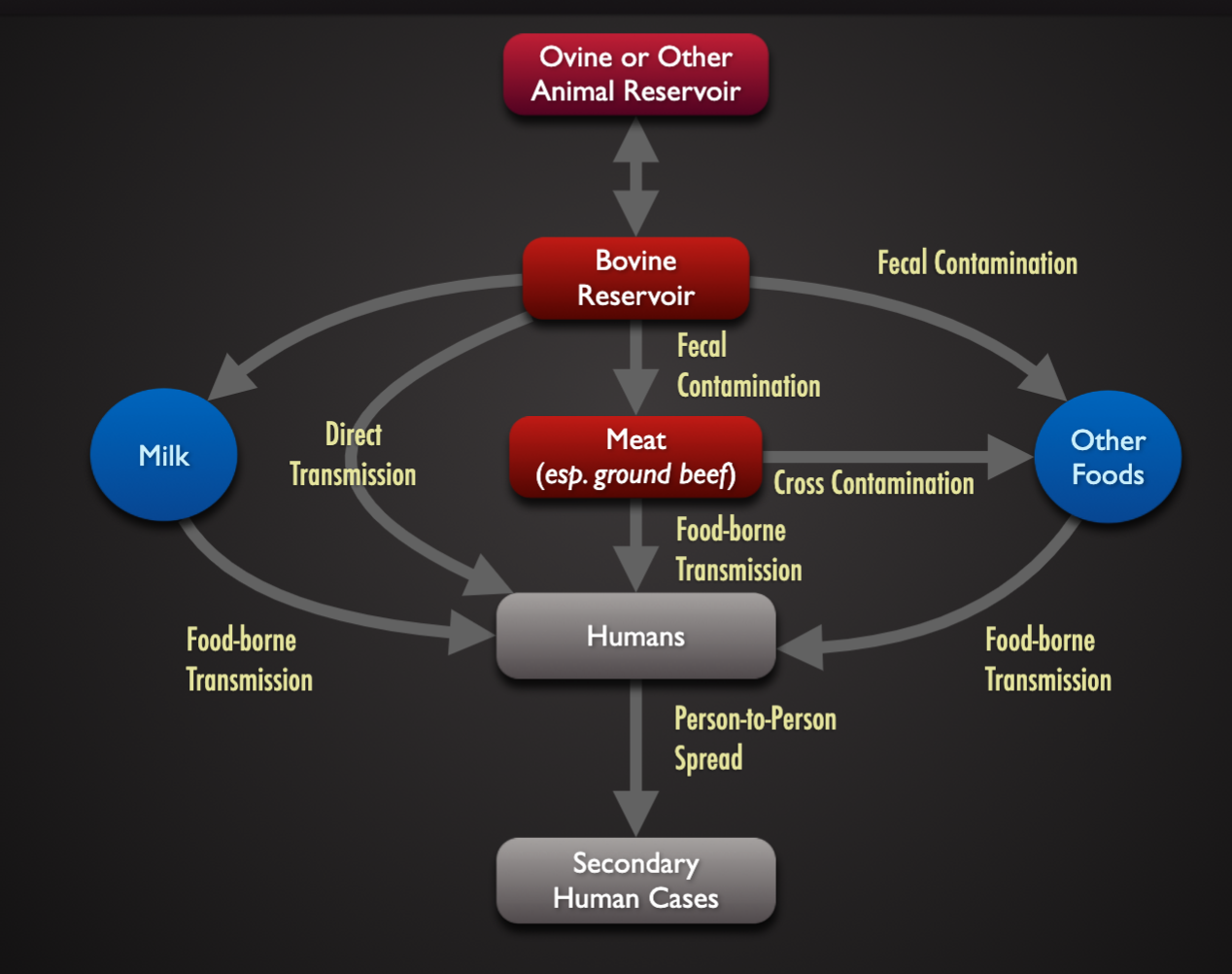

Reservoir: the natural habitat (living or nonliving) in which a pathogen lives and reproduces that serves as a source of infection

Living reservoir may be symptomatic or asymptomatic

Asymptomatic:: harder to identify and control spread (up to 50% of women infected with Neiserria gonorrhoeae are asymptomatic).

Exclusively human reservoirs are easier to control (Smallpox)

Non-human reservoirs (arthropod, wild animal) challenging to control)

Environmental reservoir: difficult or impossible eliminate (Bacillus anthracis)

Portals of entry and exit

Skin: nicks, abrasions, punctures, incisions

Gastrointestinal tract: food, drink, and other ingested materials

Respiratory tract: oral and nasal cavities

Urogenital tract: sucal, displaces organisms

Transplacental

feces/urine

semen/ vaginal secretions

Sputum

Saliva

Blood

Pus and lesion exudates

Tears

Vomit

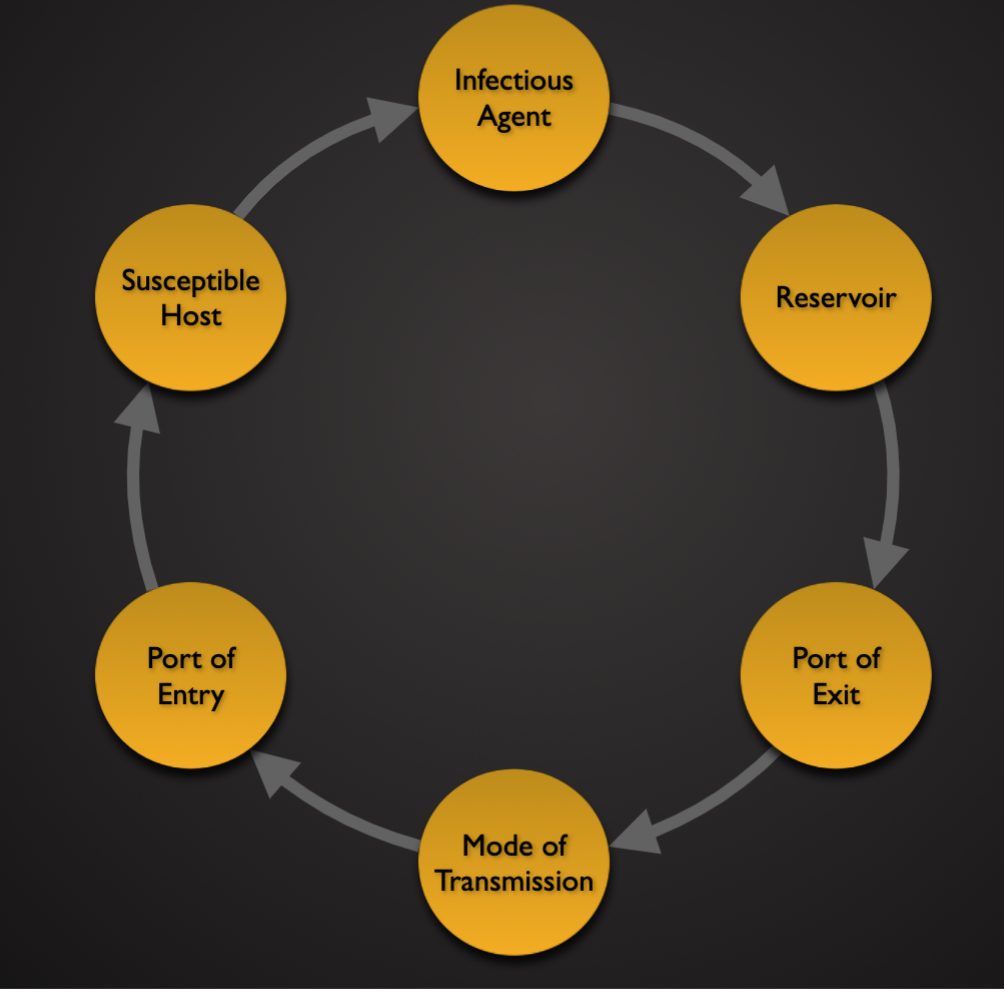

Cycle of transmission

Reservoirs and Modes of Transmission

Epidemiology Part 2 - 02.06

Frequency of Cases

Prevalence: the total number or proportion of cases or events or conditions in a given population

Incidence: the number of new cases during a specified time period

Morbidity rate: number of people affected with certain diseases during a given period of time

Mortality rate: number of deaths in a population due to certain disease during a given period of time

Case-fatality rate: the percentage of people with a specific disease that dies from that disease

Attack rate: number of people affected by a disease divided by the number of people with a specific exposure

Disease Occurrence Patterns

Endemic: a relatively steady frequency over a long period of time in the particular geographic locale (ex. Common cold)

Sporadic: when occasional cases are reported at irregular intervals (ex. Rabies in the US)

Epidemic: increasing prevalence of a disease beyond what is expected (ex. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) in the US in 2013)

Pandemic: epidemic across countries and continents (HIV/AID, COVID-19)

In an outbreak of aflatoxicosis among finishing pigs in a farm of 200 pigs: 100 pigs ate feed mixed using an old batch of corn. 20 pigs first began vomiting. A day later, 30 more pigs showed similar symptoms. Over the course of the week, 10 pigs died.

What is the prevalence of aflatoxicosis? 25%

What is the case fatality rate? 20%

What is the attack rate? PB: 50%

Basic Reproductive Number (R0)

The average number of new infectious generated by one infection in a completely susceptible population

Measure of the intrinsic potential of an infectious agent to spread

R0 = C x P x D

C = contact rate (contact/time)

The average rate of contact between susceptible and infected individuals

P = transmissibility (infection/contact)

The probability of infection given contact between a susceptible and infected individuals

D = duration of infectiousness (time/infection)

Effective Reproductive Number ( R )

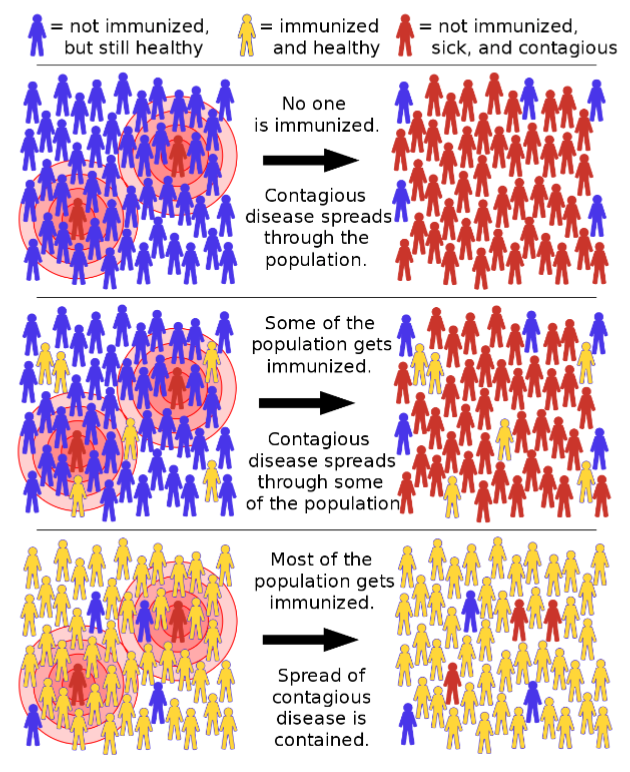

A population will rarely be totally susceptible to an infection in the real world. The effective reproductive rate ( R ) estimates the average number of secondary cases per infectious case in a population made up of both susceptible and non-susceptible hosts.

R= R0 x S

R0 = Basic reproductive number

S = fraction of the host population that is susceptible

Endemic vs. Epidemic

Newyrok of Infection

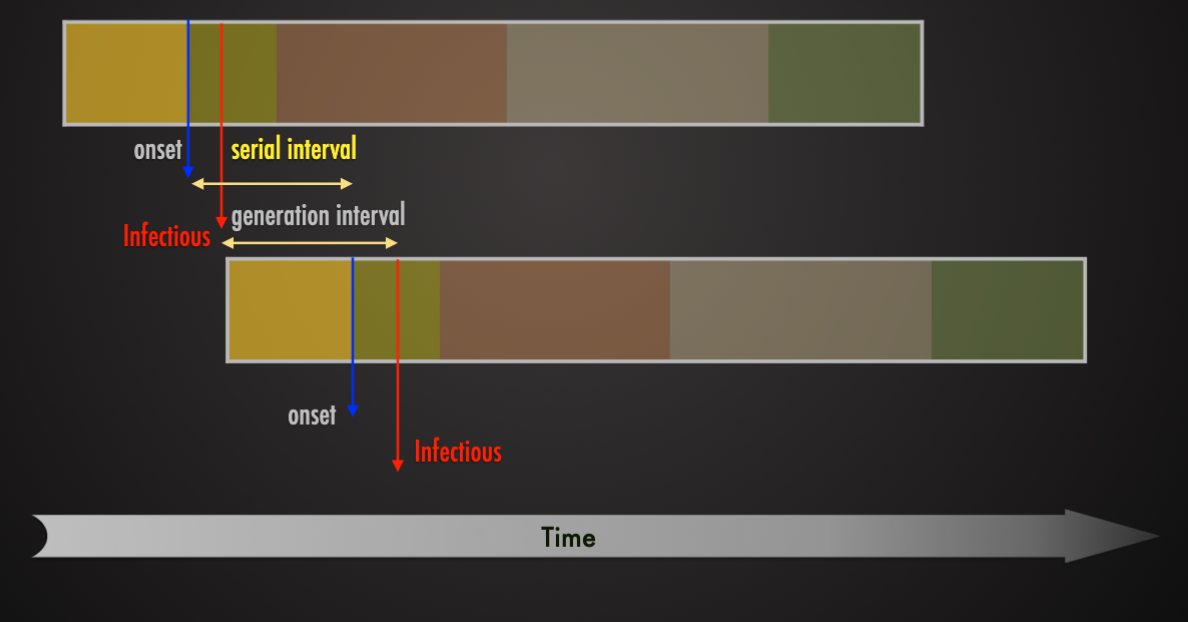

Rate of spread of an infection depends on R0 and serial interval

Serial Interval

The time between the same stage of illness in successive clinical cases in a chain of transmissions

SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome)

Outbreak: November 2022 - July 2033

Causes by SARS coronaviru (SARS-CoV)

Spread across 37 countries and regions

Infected 8,098 people (reported cases)

Killed 774 people (killed 1 in 10 people infected)

Spatial Heterogeneity

Rural Areas

Urban Areas

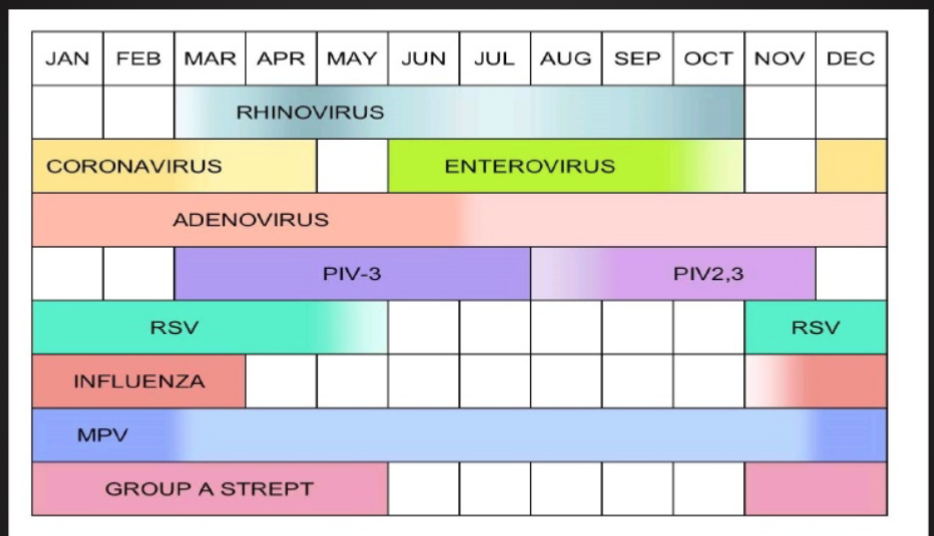

Seasonality of Infections

Why? What causes seasonality?

Climate, temperature, moisture levels, allergies

Impact of Movement and Modern Transport

Pathogenesis of Infections 02.08.24

Germ Theory

Robert koch

Louis pasteur

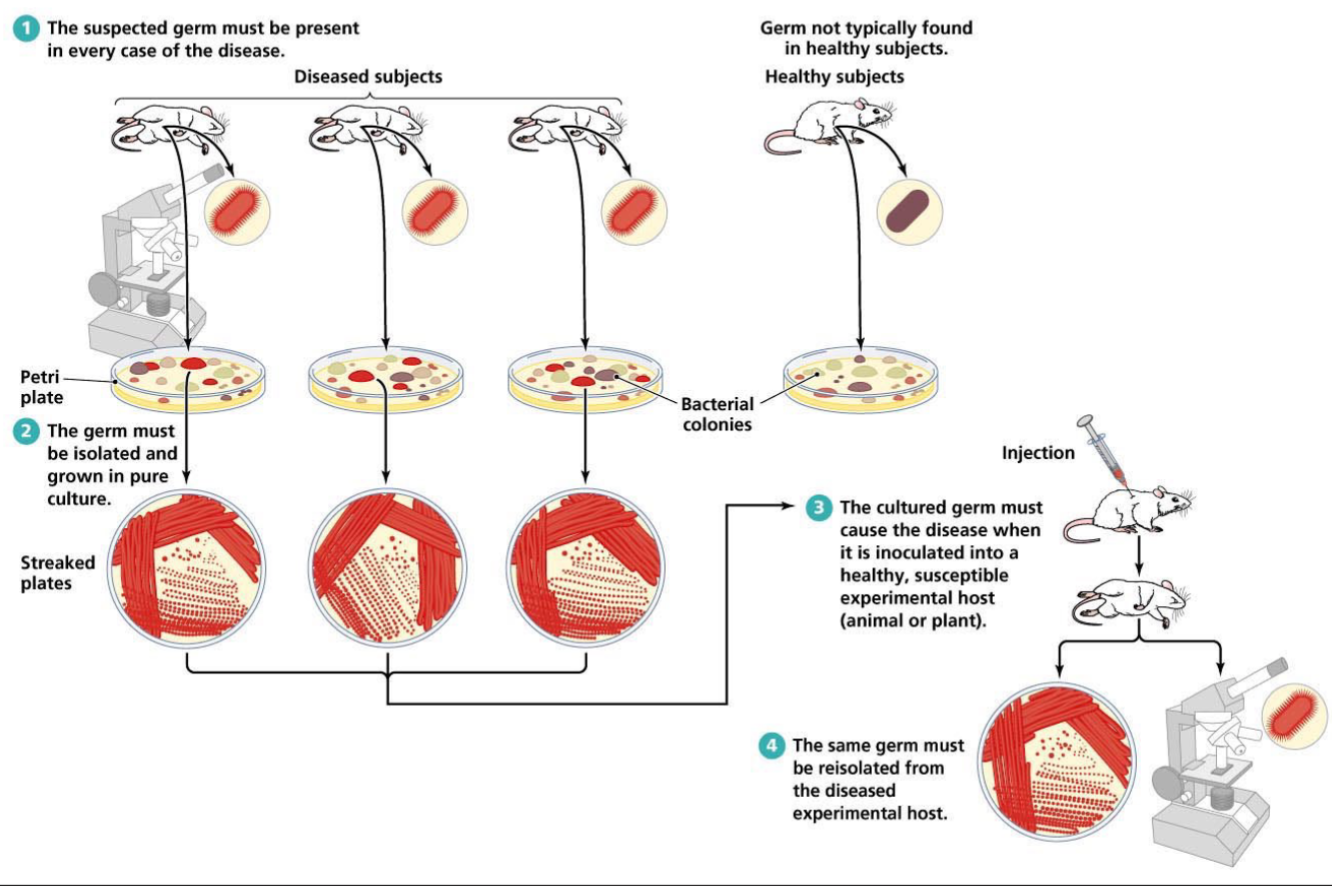

Koch’s Postulates

The microorganism must be found in abundance in all organism suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy organisms

The microorganisms must be isolated from a diseased organism and grown in pure culture

The cultured microorganisms should cause disease when introduced into a health organism

The microorganism must be reisolated from inoculated, diseased experimental jost and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent

The suspect germ must be present in every case of the disease

The germ must be isolated and grown in pure culture

The cultured germ must cause the disease when it is inoculated into health, susceptible experimental host (animal or plant)

The same germ must be reisolated from the diseased experimental host

Infectious Agents

Bacteria

Viruses

Protozoa

Fungi

Parasitic worms (helminths)

Prions

Introduction to Bacteria

Bacterial taxonomy

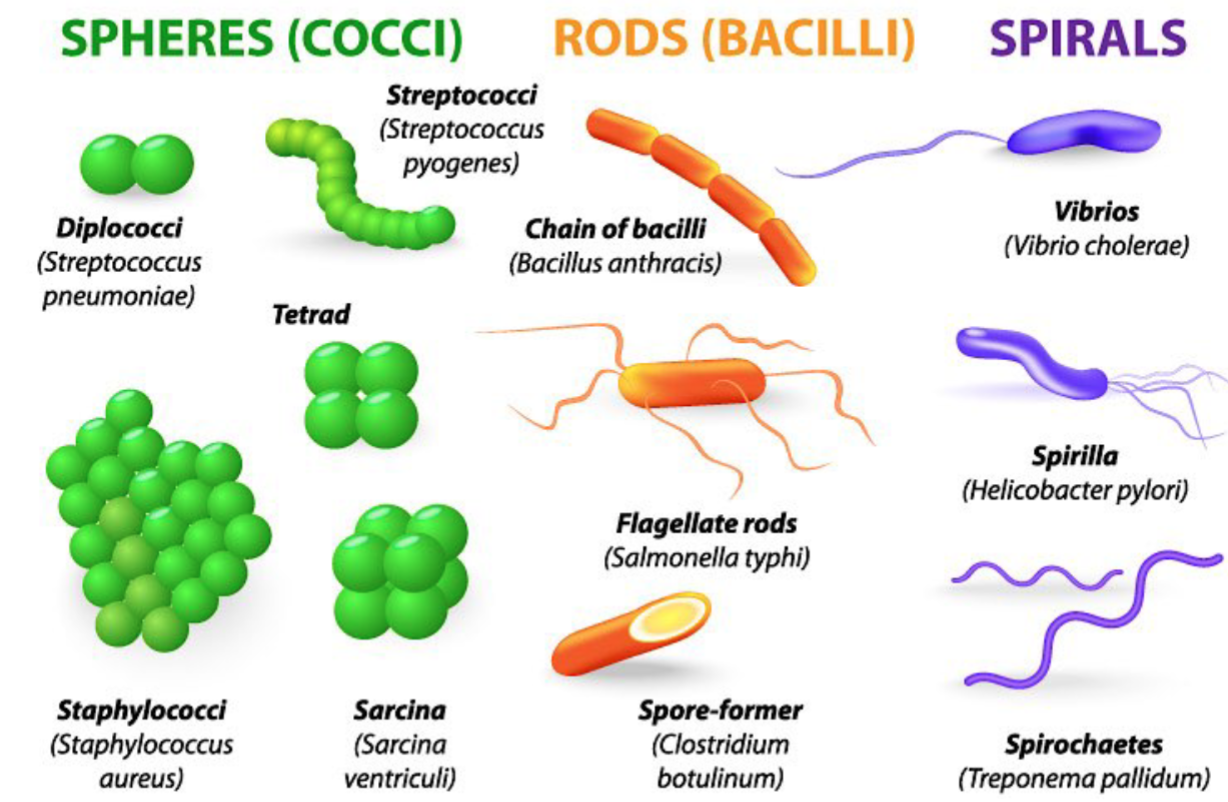

Bacterial Shapes

Coccus

Coccobacillus

Bacillus

Cocobacillus

vibrio

Spiral

Vibrio

Bacterial Shapes

Bacteria Cell Structure

Flagella

Presence is species.strain dependent

For motility

Number and arrangement vary

Pili/Fimbriae

Hair-like structures

Fimbriae shorter than pili

Adhere.attach to surfaces (key step in most infections

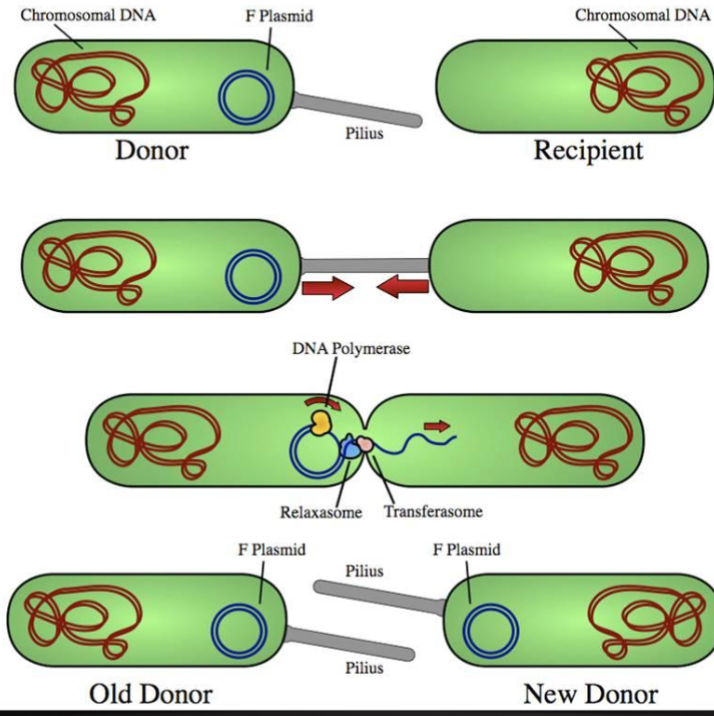

“F” or sex pilus: used for transfer of genetic material (plasmid) from one bacteria to another

Can provide resistance against engulfment by phagocytes

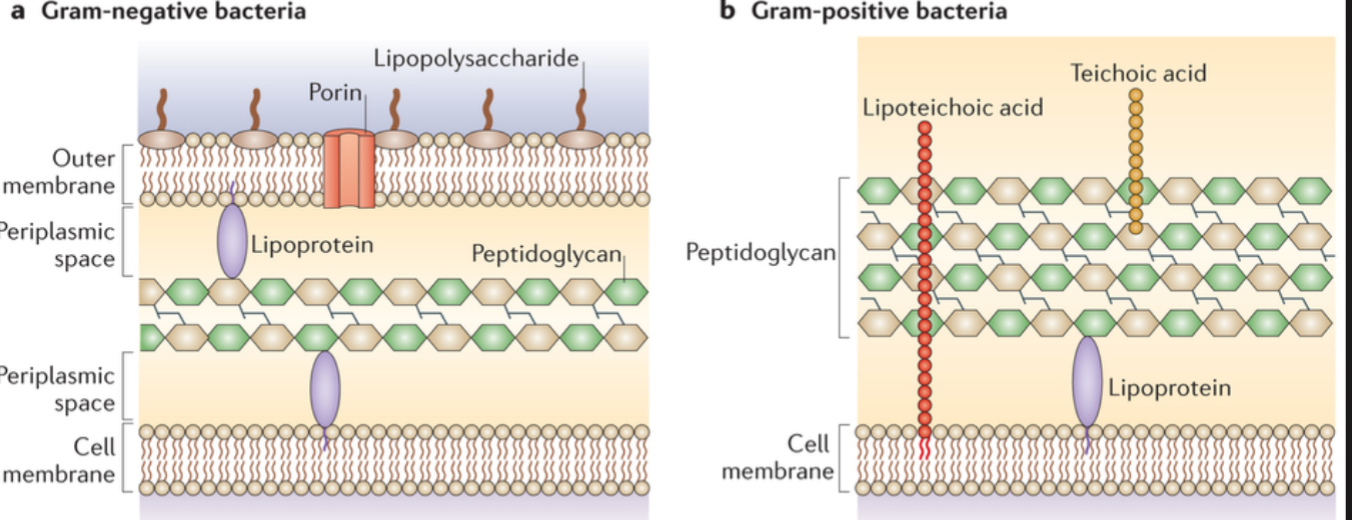

Bacterial Cell Wall Structure

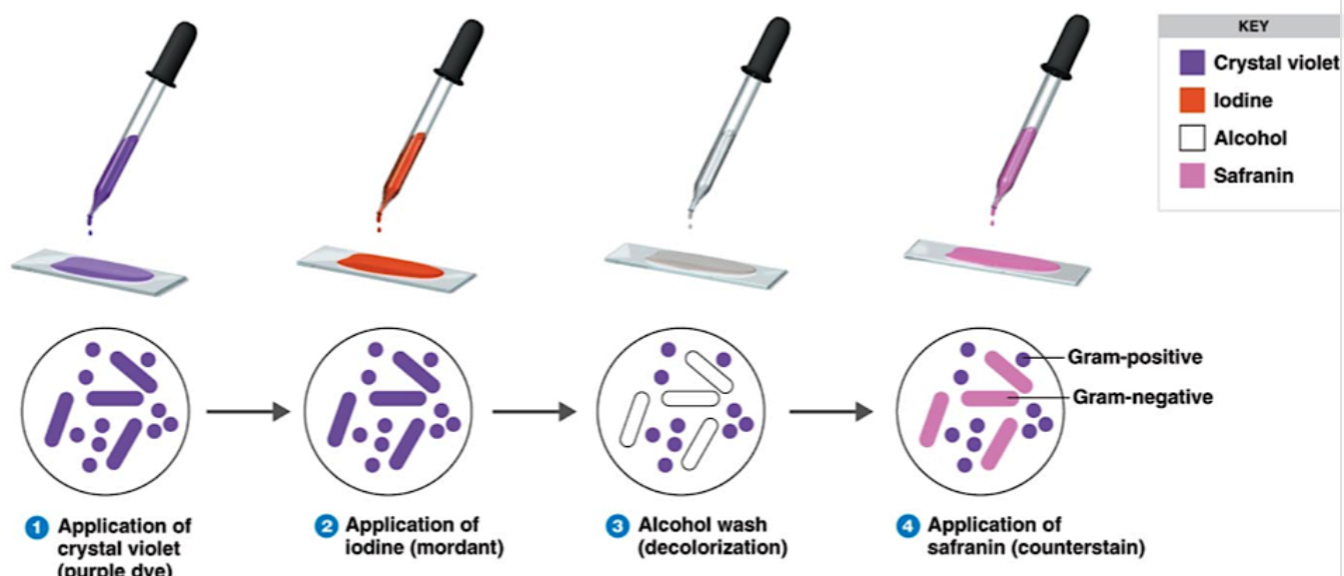

Gram Staining

Application of crystal violet

Application of iodine

Alcohol wash

Application of safranin

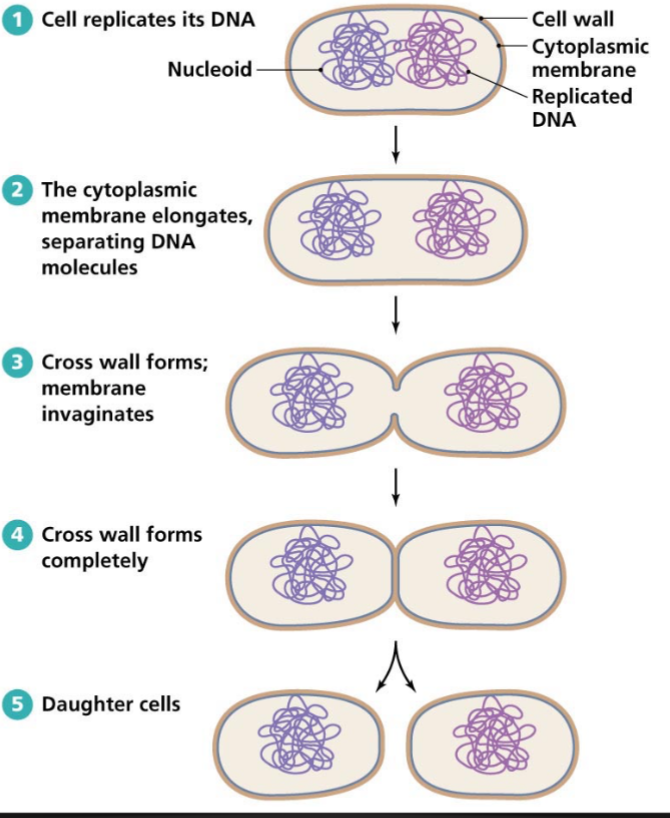

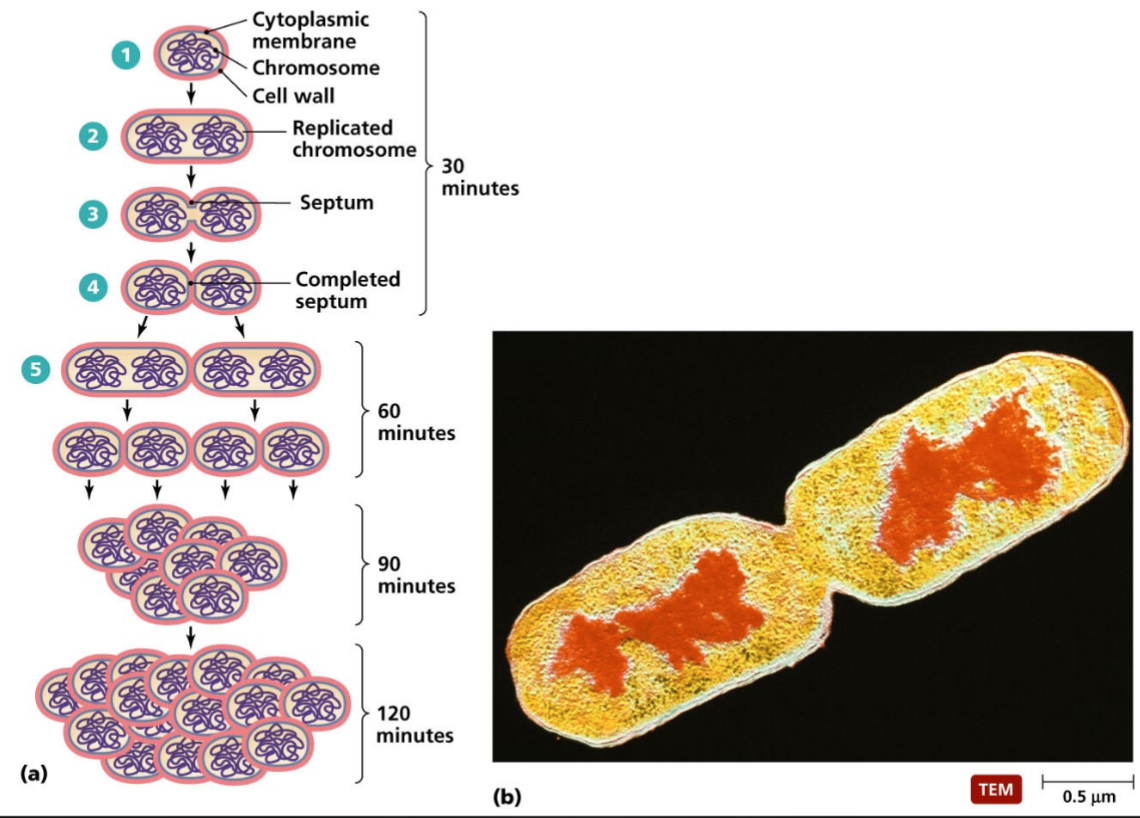

Bacterial Reproduction

Cell replicate its dna

The cytoplasmic membrane elongates, separating DNA molecules

Cross wall forms completely

Daughter cells

Rapid Bacterial Growth

Cytoplasmic membrane

Replicated chromosome

Septum

Completed septum

60 mins – 90 mins – 120 mins

Bacterial Endospore Formation

Under stressful environments, certain gram positive bacteria are capable of forming endospores

Endospores can survive environmental assaults that would normally kill the bacteria. These stresses include high temperature, high uv irradiation, desiccation, chemical damage and enzymatic destruction

Endospores make them of particular importance because they are not readily killed by manu antimicrobial treatments

Types of Bacterial Pathogen

True pathogen (enterotoxigenic escherichia coli): infectious agent that causes disease in virtually any susceptible host

Opportunistic pathogen (pseudomonas, staphylococcus): normally harmless, causes disease when the normal flora is disrupted (by antibiotics) or when the host is immunocompromised (by drugs or other illnesses).

Bacterial Adhesion

Necessary to avoid innate host defense mechanisms ( peristalsis in the hugy and the flushing action of mucus, saliva and urine).

Adhesion is often an essential preliminary step to colonization and then penetration through tissues

At the molecular level, adhesion involves surface interactions between specific receptors on host cell membrane and ligands on the bacterial surface

Nonspecific surface properties of the bacterium. Including surface charge and hydrophobicity, also contribute to the initial stages of the adhesion process

Mechanism of Adherence to cell or tissue surfaces

Non-specific adherence: reversible attachment to the surface (dock)

Hydrophobic interactions

Electrostatic attractions

Atomic and molecular vibrations resulting from fluctuating dipoles of similar frequencies

Brownian movement

Recruitment and trapping by biofilm polymers interacting with bacterial glycocalyx (capsule)

Specific adherence: irreversible permanent attachment to the surface (anchoring)

Formation of many specific lock and key bonds between complementary molecules on each cell surface

Complementary receptor and adhesion molecules must be accessible and arranged in such a way that many bonds form over the area of contact between the two cells.

Once the bonds are formed, attachment under physiological conditions becomes virtually irreversible.

Specific adherence of bacteria to cell or tissues

Tissue tropism

Particular bacteria are known to have apartment preference for certain tissues over others

Ex s mutans is on dental plaque but not on tongue surfaces

Species specificity

Certain pathogenic bacteria infect only certain species of animal

Genetic specificity within a species

Certain strains or races within a species are genetically immune to a pathogen

Terminology: Adherence factors in host-pathogen interactions

Adhesion

A surface structure or macromolecule that binds a bacterium to a specific surface

Receptor

A complementary macromolecular binding site on a (eukaryotic) surface that binds specific adhesins or ligands

Lectin

Any protein that binds to a carbohydrate

Ligand

A surface molecule that exhibits specific binding to a receptor molecule on another surface

Mucous

The mucopolysaccharide layer of glycosaminoglycans covering animal cell mucosal her for the purpose of DNA transfer surfaces

Fimbriae

Filamentous proteins on surface of bacterial cells that often have adhesins for specific adherence

Common pili

Same as fimbriae

Sex Pilusx

A specialized pilus that binds mating prokaryotes together for the purpose of DNA transfer

Type 1 fimbriae

Fimbriae in enterobacteriaceae which bind specifically to mannose terminate glycoproteins on eukaryotic cell surfaces

Type 4 pili

Pili in certain gram - and gram + bacteria. In pseudomonas, thought to play a role in adherence and biofilm formation

S-layer

Proteins that form the outermost cell envelope component of broad spectrum of bacteria, enabling them to adhere to host cell membranes and environmental surfaces

Glycocalyx

A layer of exopolysaccharide fibers on the surface of bacterial cells which may be involved in adherence to a surface. Sometimes a general term for capsule

Capsule

A detectable layer of polysaccharide (rarely polypeptide) on the surface of a bacterial cell which may mediate specific or nonspecific attachment

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)

A distinct cell wall component of the outer membrane of gram- negative bacteria with the potential structural diversity to mediate specific adherence. Probably functions as an adhesin

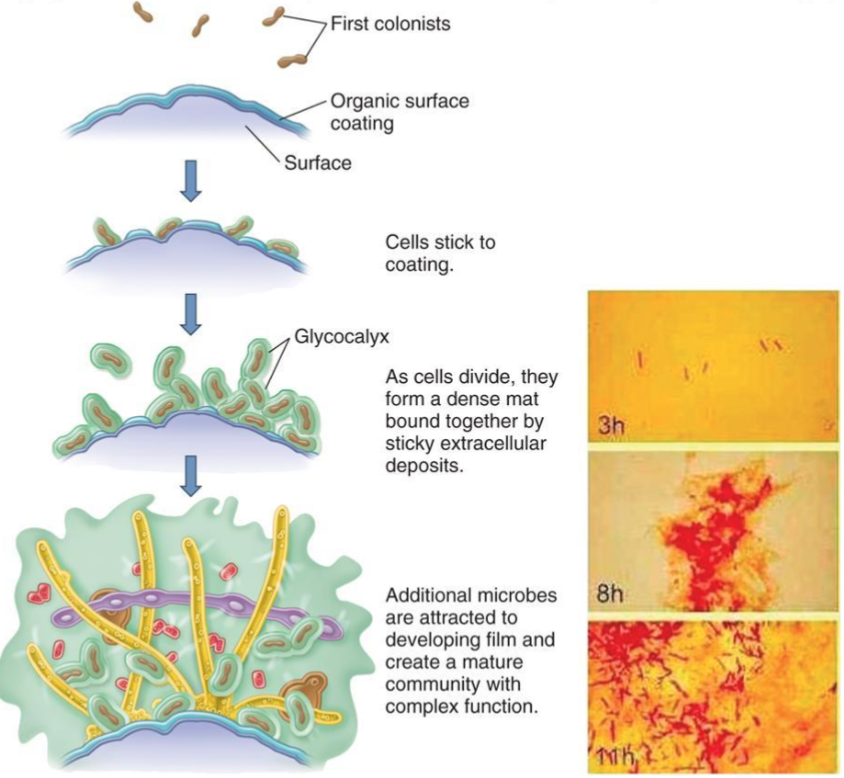

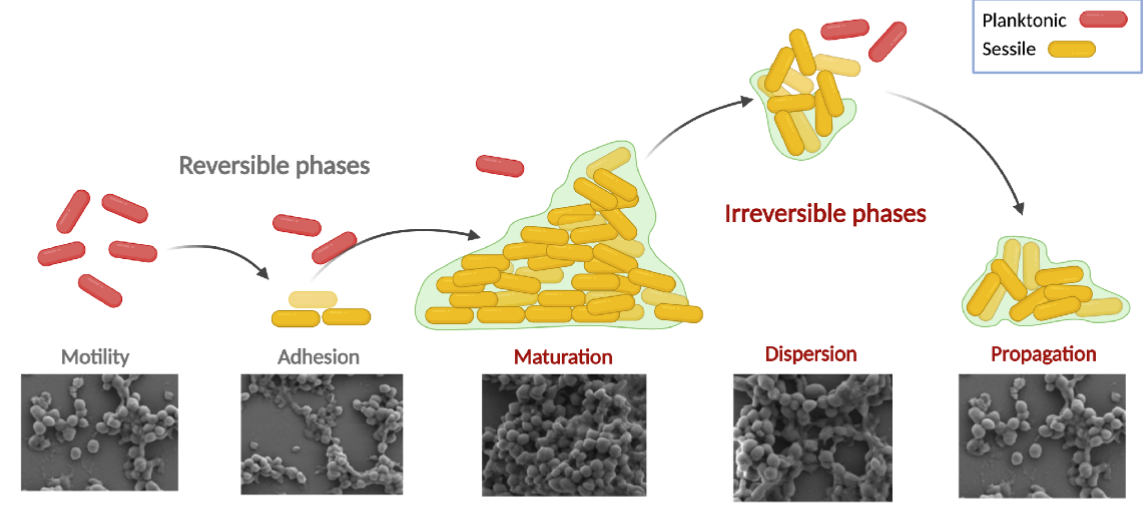

Bacterial Biofilm Formation

Aggregate of microorganisms in which cells that are frequently embedded within a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substance adhere to each other and surfaces

Form on tissue surfaces (ex teeth, skin, mucosal membrane ) and inanimate surface (ex catheters kitchen counters, orthopedic implant)

Often impervious to detergents, antibiotics and immune system

Can act as reservoirs for repeated infections

Know the definitions

Planktonic cells

biofilm -enmeshed cells

Persisters cells

Bacterial Pathogens

Facultative intracellular pathogen

Salmonella, shigella, yersinia

Obligate intracellular pathogen

Ex. rickettsia, chlamydia, coxiella

Extracellular pathogen

Ex. vibrio cholera, pseudomonas E. coli (ETEC)

Bacterial Pathogens

Facultative intracellular pathogen

Ex. salmonella, shigella, yersinia

Obligate intracellular pathogen

Ex. rickettsia, chlamydia, coxiella

Extracellular pathogen

Ex. Vibrio cholera, pseudomonas, E. coli (ETEC)

Bacterial Invasion

Penetration of host cells and tissues (beyond the skin and mucous surfaces)

Mediated by a complex array of molecules, often described an “invasins”

Invasins can be in the form of bacterial surfaces or secreted proteins which target host cell molecules (receptors)

Bacterial Invasins: Spreading Factors

Descriptive term for a family of bacterial enzymes that affect the physical properties of tissue matrices and intracellular spaces, thereby promoting the spread of the pathogen

Hyaluronidase:

Produced by streptococci. Staphylococci, and clostridia

Attacks the interstitial cement (“ground substance”) of connective tissue by depolymerizing hyaluronic acid

Collagenase

Produced by clostridium histolyticum and C. perfringens

Breaks down collagen, the framework of muscles, which facilitates has gangrene due to these organism

NeuraminidaseL

Produced by intestinal pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae and Shigella

Degrades neuraminic acid (also called sialic acid), an intercellular cement of the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa

Streptokinase and staphylokinase

Produced by streptococci and staphylococcus, respectively

Digests fibrin and prevents clotting of the blood

Relative absence of fibrin in spreading bacterial lesions allows more rapid diffusion of the infectious bacteria

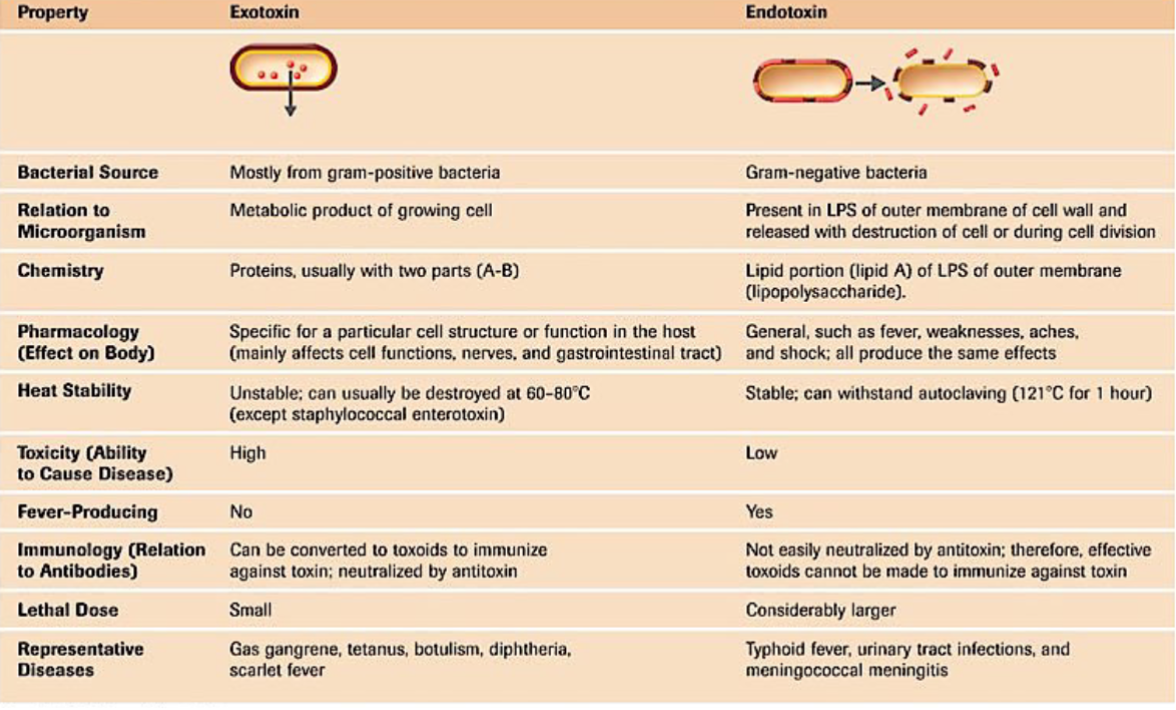

Bacterial Toxigenicity

exotoxins

Proteins produced inside pathogenic bacteria

gram-positive bacteria

Retain high activity at very high dilutions

Endotoxins

Lipid potions of LPS, outer membrane of cell wall

Gram-negative bacteria

Virulence Factors

Adhesion

Invasion

Competition for iron and nutrients

Resistance to host immunity

Secretion of toxins

Bacterial Conjugation: Propagation of Virulence

Biofilms - 02.13.24

Biofilm

Highly structured microbial communities enmeshed in a self-produced slime matrix comprised of proteins, polysaccharides, eDNA, and lipids

Biofilms are highly complex

Stringy: only contains eDNA

Chunky: only contains proteins

Webby: contains everything

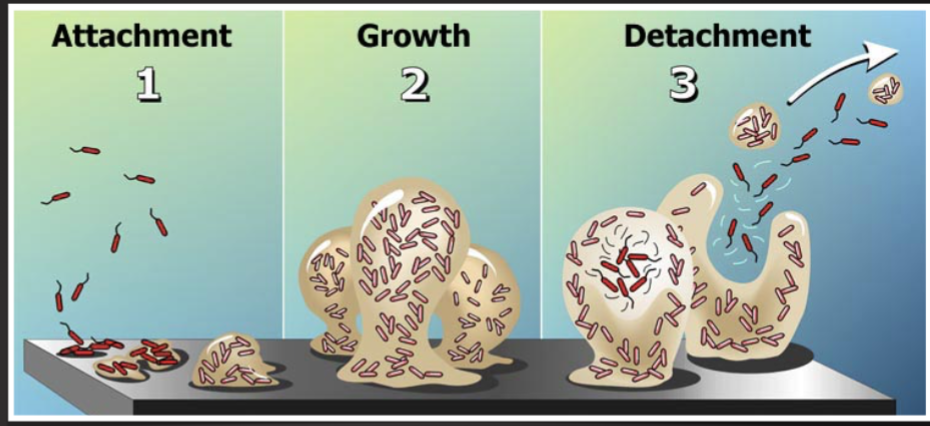

Biofilm Development Stages

colonization/adhesion

Non-specific attachment

Physio-chemical

Pili-mediated

flagella-mediate

Specific attachment

Receptor-mediated

host-ECM components

Aggregation

microlony/monolayer formation

Maturation

Dispersal

Biofilm EPS formation, Maturation (3-5)

Bacterial communication

Quorum sensing

Biofilm Dispersal (6)

Bacterial-mediated

Matrix degradative enzymes

Dissemination

Persistence

Why form biofilm

To protect from predators

Cooperation strategy for bacteria

Biofilms provide a nutritional advantage for the bacteria

To establish dominance in the environment

Biogenic Habitat-Forming Organisms

protection/safety

Shelter

Stress response

Predator evasion

Polymicrobial Nature

Biofilms are predominantly polymicrobial

Multiple bacterial species

Multi-organism communities

Bacterial-fungal and agal biofilms

High Bacterial Diversity = high survival

Biofilm = sponge

High diversity

Enhance EPS profile

High nutrition absorption

Enhance metabolic capacity

High ability to breakdown complex molecules

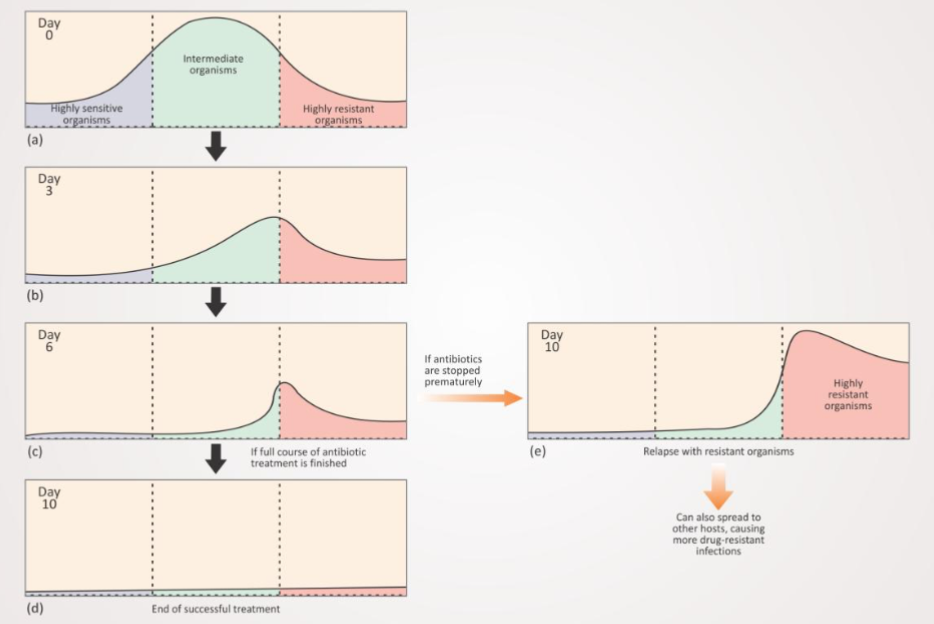

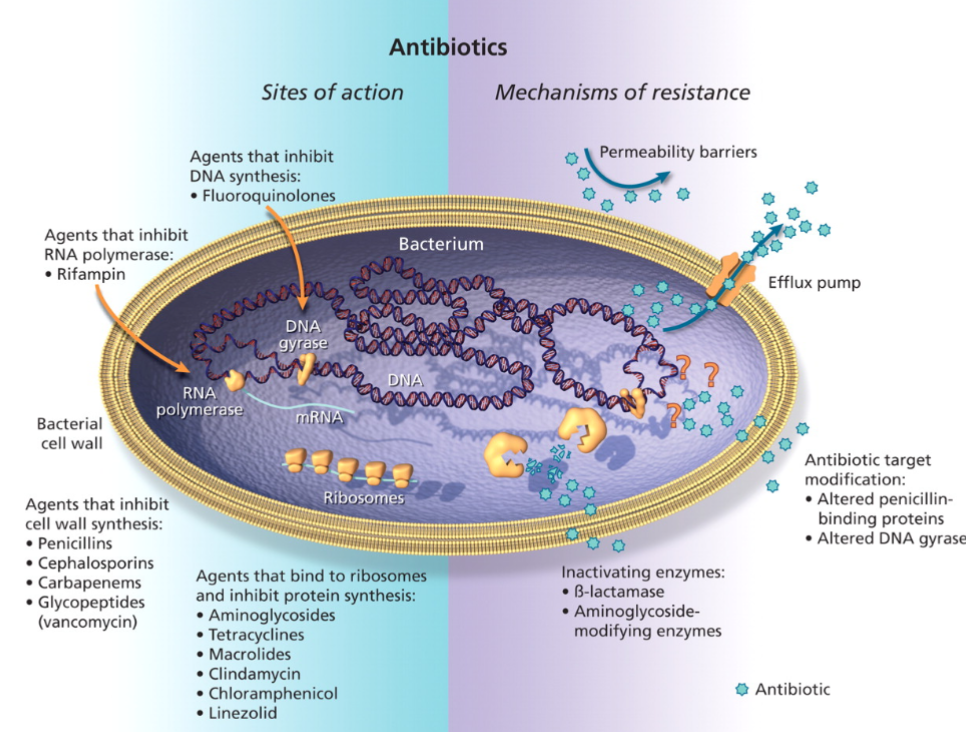

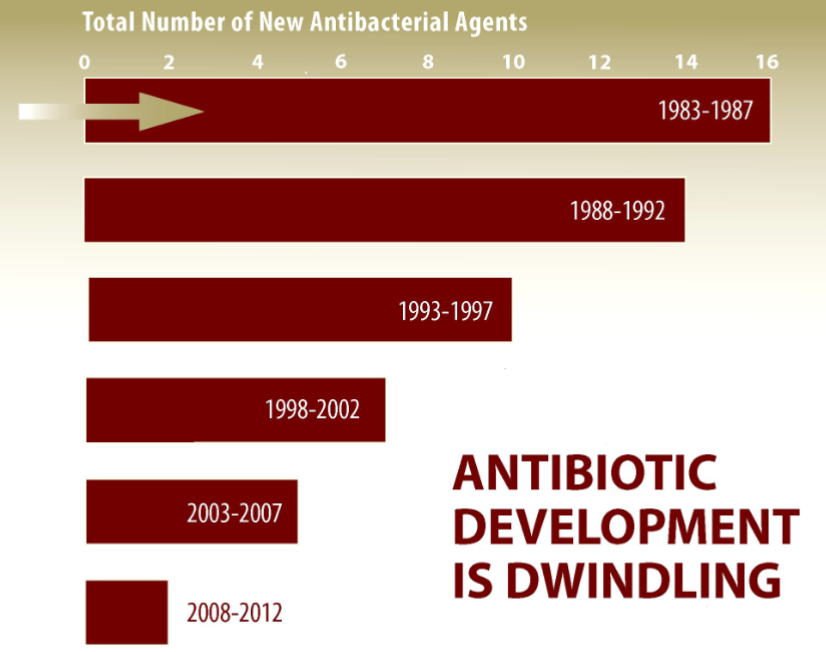

Antimicrobial/Antibiotic Resistance

Bacteria acquire/develop mutations that render the antibiotic/toxin ineffective

How?

Intrinsic resistance

Inherited physiological property

Cell wall (gram-, gram +)

Acquired resistance

Mutations

Gene acquisition

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT)

Antimicrobial/ Antibiotic Tolerance

Ability to survive transient exposure to a high concentration of an antibiotic, despite being susceptible

How

Intrinsic tolerance

Inherited physiological property

Spore formation

Biofilm formation

Acquired tolerance

Physiological property

Join a biofilm

Dormancy (metabolic shutdown)

Persister cells

Multi-Species Biofilm = Multi-functional biofilm

Why Biofilms

Environmental stress

Predator evasion

Nutrient acquisition

Antibiotic tolerance/ resistant

Horizontal gene transfer

Biofilm Infections

Approx. 34% of nosocomial infections

65% of all microbial infections

80% of chronic infection

Biogilm infection chronicity

Biofilm prolong/ prevent wound healing

Re-epithelialization

Granulation tissue formation

Manipulation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses

Anti-biofilm Strategies are difficult

Antibiotics are becoming ineffective

Metals such as silver and zinc can be toxic

Debridement procedures are aggressive and invasive

Preventative strategies are god but not enough

Wash hands

Cover coughs and sneezes

Clean surfaces

Adequate ventilation

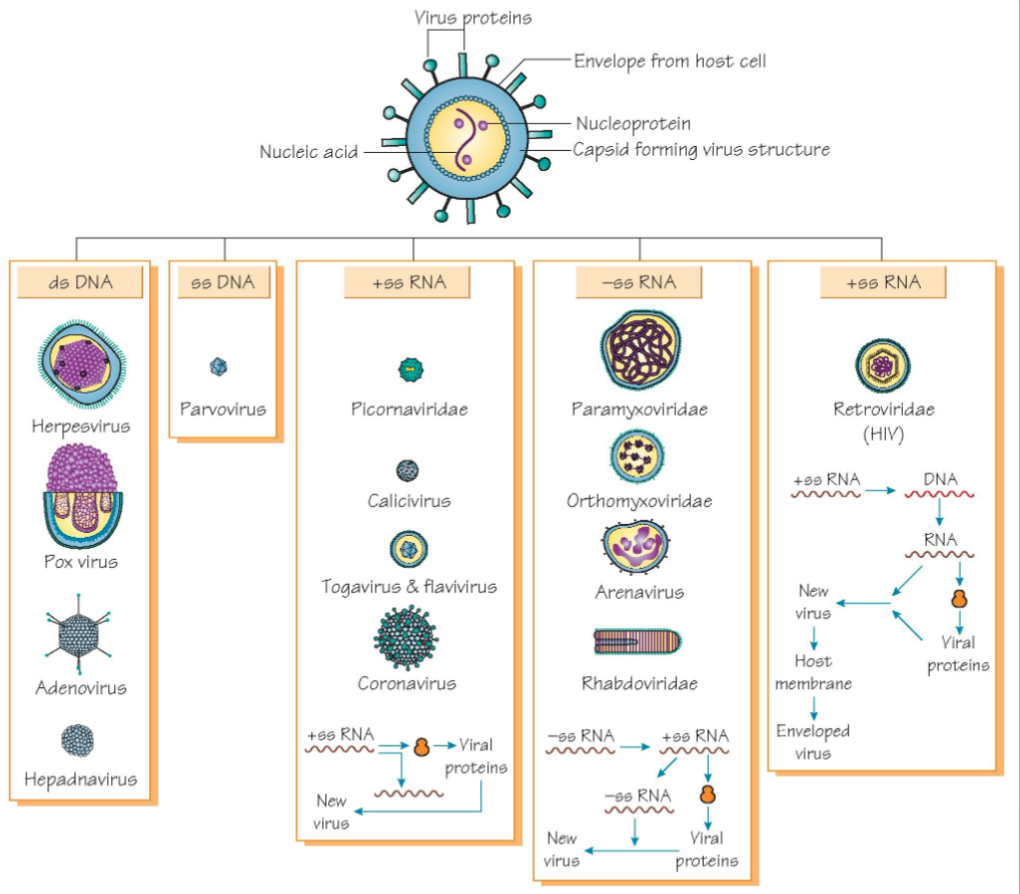

Introduction to Viruses - 02.15

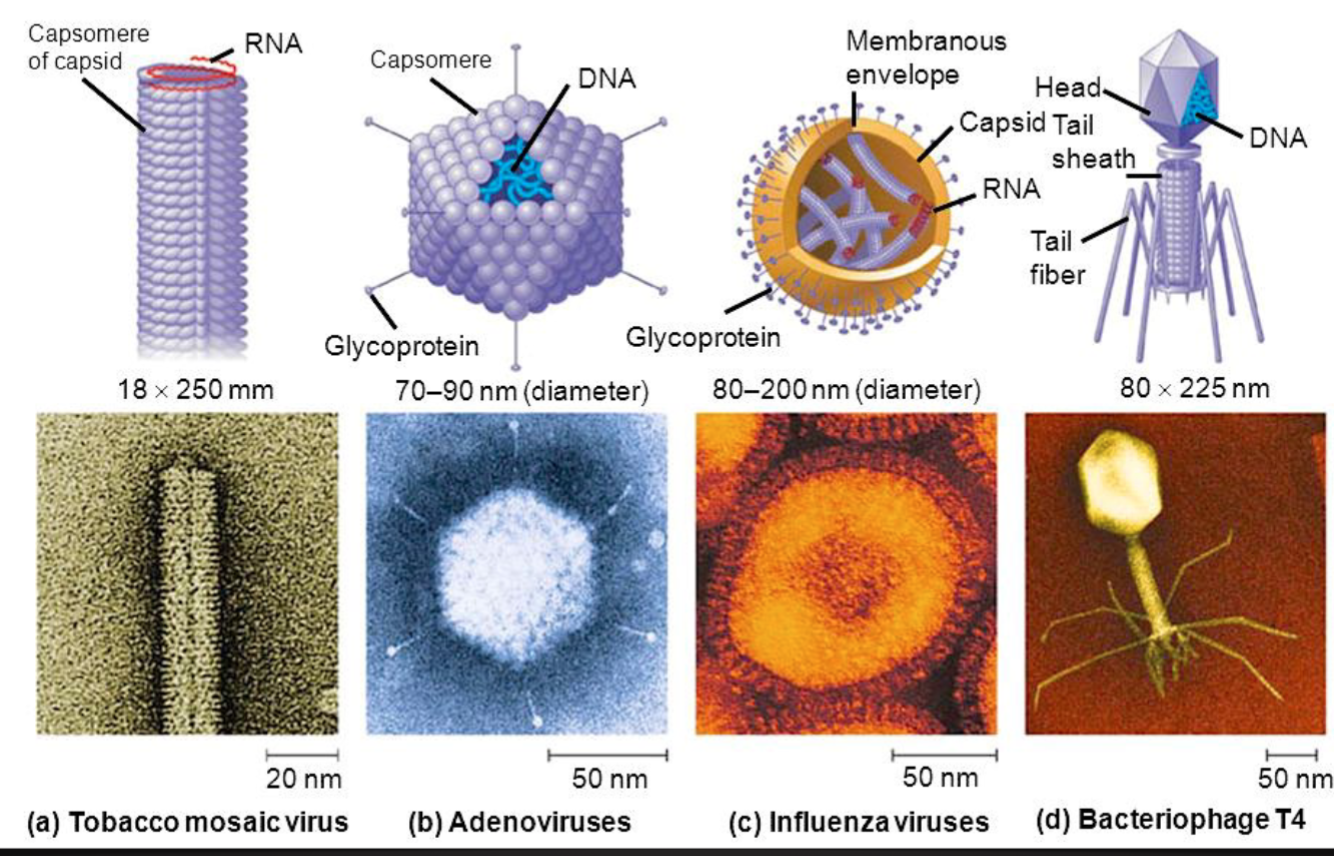

Virions/Viruses

Acellular and the virion consist of

DNA or RNA core

Single-stranded positive-sense RNA

Single-stranded negative-sense RNA

Double stranded RNA

Double stranded DNA

Protein coat (capsid)

Lipid envelope (on some viruses) and “spikes” (glycoproteins

Viruses can infect all types of life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria (“bacteriophage”) and archaea.

Can replicate only when within living host cell;

General rule: DNA viruses replicate within the nucleus while RNA viruses replicate within the cytoplasm

Viruses: Structure

Structuve

Viral proteins

Envelop from host cell

Capsid forming virus structure

Nucleic acid

Nucleoprotein

Viruses: Classification

Two Systems of Classification

Hierarchical virus classification system

Four Main characteristic are used

Nature of nucleic acid: RNA or DNA

Symmetry of the capsid

Presence or absence of an envelope

Dimensions of the virion and capsid

The Baltimore Classification

Viruses can be classified into seven (arbitrary) groups

Double-stranded DNA

Single stranded (+) sense DNA

Double-stranded RNA

Single stranded (+) sense DNA

Single stranded (-) sense RNA

Single-stranded (+) sense with RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle

Double stranded DNA with RNA intermediate

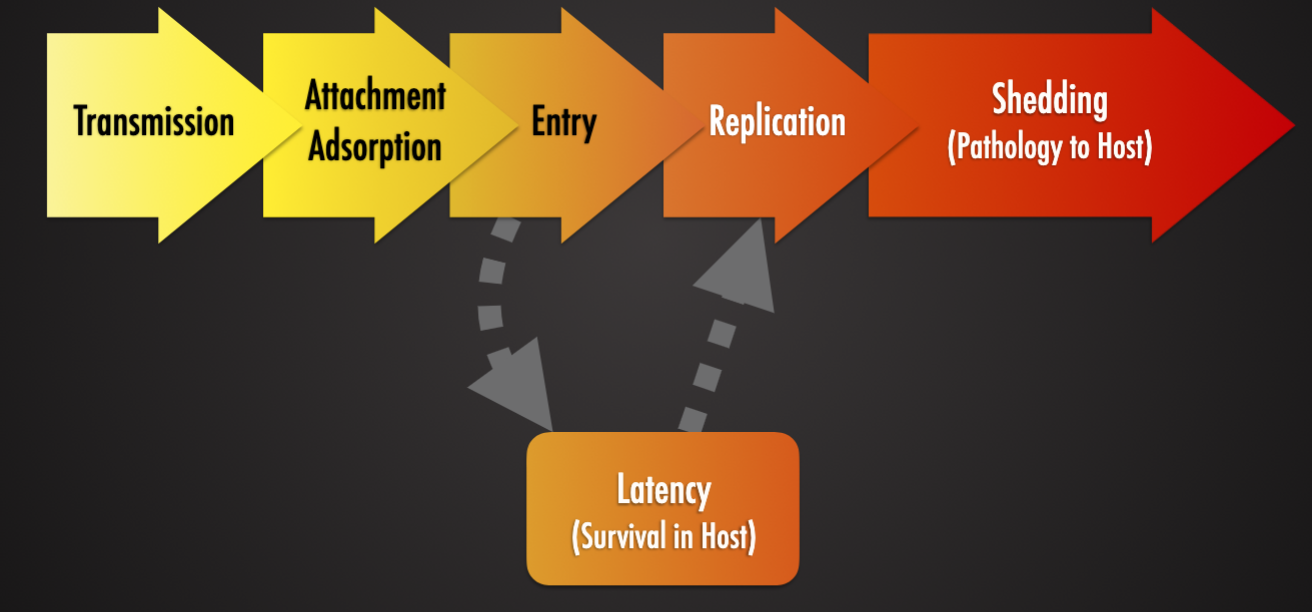

Viral Pathogenesis

Viral Attachment and Entry

Direct penetration

Viral capsid or genome is inject into the host cell’s cytoplasm (poliovirus)

Membrane Fusion

The cell membrane is punctured and made to further connect with the unfolding viral envelope (influenza virus)

Endocytosis

The host cell engulfs and takes in the viral particle (HIV)

Viral Replication

Uncoating

Stripping off the viral protein coat, releasing the viral nucleic acid or genome

Transcription / mRNA production

Virus takes advantage of host cell structures to replicate itself

For some RNA viruses, the infection RNA produces messenger RNA (mRNA) for translation into protein (virus components).

For others with negative stranded RNA and DNA, transcription occurs before translation

Synthesis of virus components:

Viral protein synthesis: virus mRNA is translated on host cell ribosomes into two types of viral protein

Viron assembly

Newly synthesized genome (nucleic acid), and proteins are assembled to form new virus particles (virions)

Can occur at the cell’s nucleus, cytoplasm or plasma membrane

Viral Latency

Ability of some viruses to remain dormant within the host dell (occult infection), sometimes for years

Viral genome can remain latent either as an episome or integrated in the host chromosome. The latter allows for replication of viral genome during host cell division

Latency is maintained by a few viral genes that keep viral genome silent and escape from host immune system

Latency can stop upon viral genome reactivation, often promoted by external stimuli (host stress cellular signals)

Viruses with the ability for latency have two options when infecting a cell:

Enter the latency or the lytic pathway. The decision is regulated by expression of regulatory proteins part of a genetic switch system, usually repressor(s) as well as proteins controlling the stability of the latter. The outcome depends on the ratio of these key regulators. The ratio may be determined by environmental factors such as the host cell type, its shape, or the nutrient availability.

Viral Shedding

Via Budding:

Most effective for viruses that require an envelope (HIV, smallpox)

Before budding, the viral receptor are placed on the host cell surface

Depletes host cell membrane → eventual host cell death

Via Apoptosis

Forced cell suicide released viral progeny.

As apoptotic host cells are phagocytosed by macrophages, virus has the opportunity to get into macrophages to infect or be transported to other tissues in the body

Via Exocytosis

Used by non-enveloped viruses

Host cell is not destroyed

Virus progeny are enclosed in vesicles and transported to cell membrane to be released

Protozoa 02/22/24

Pathogenesis of Infection: Protozoa 02/22/24

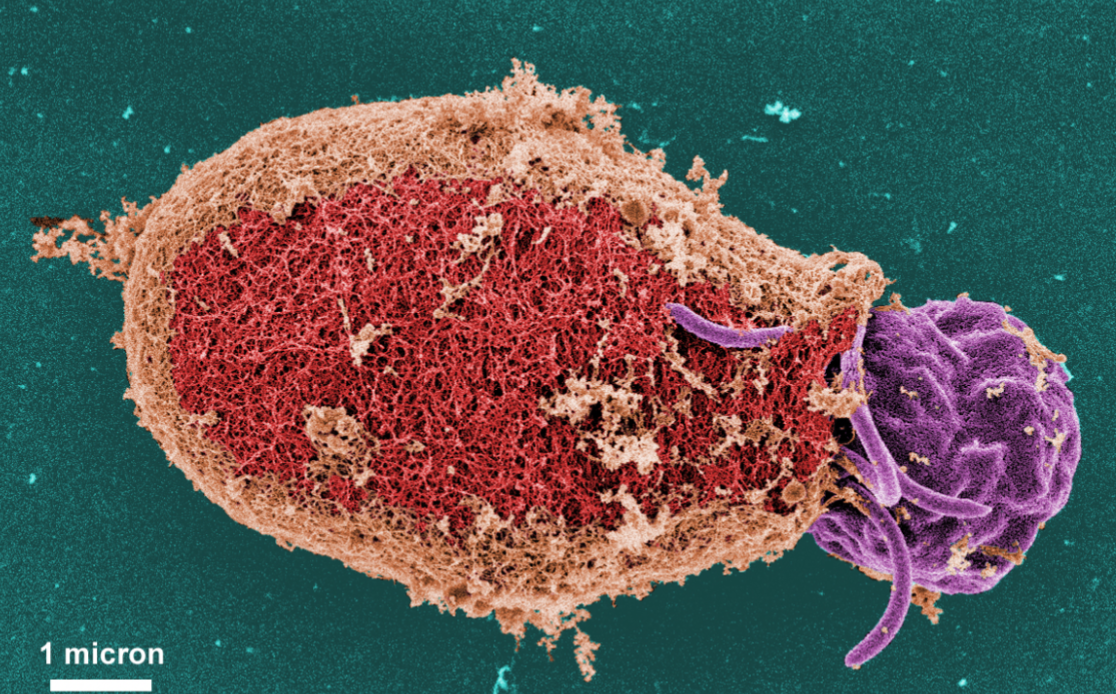

Paramecium

A protozoan

Abundant in freshwater, brackish, and marine environments (very abundant in stagnant basins and ponds)

Readily cumulative

Widely used in classrooms and labs to study biological processes

Dictyostelium Discoideum

Species of soli-living amoeba: referred to as “slime mold”

Social amoeba

Protozoan Parasites

Eukaryotic organism – “Proto-zoa” literally means “first animals”

About 32,000 living species (34,000 are extinct)

21,000 species occur as free-living organisms

11,000 species are parasitic in vertebrae and invertebrate hosts

Most protozoa are microscopic organism

Few grow to be seen by the naked eye, they are <50 um in size

Nutrition is holozoic (type of heterotrophic nutrition) as in higher animals

Via osmotrophy OR absorb nutrients through cell membrane

Via phagocytosis: engulf food particles with pseudopodia or take in food through a mouth-like aperture called a cytostome

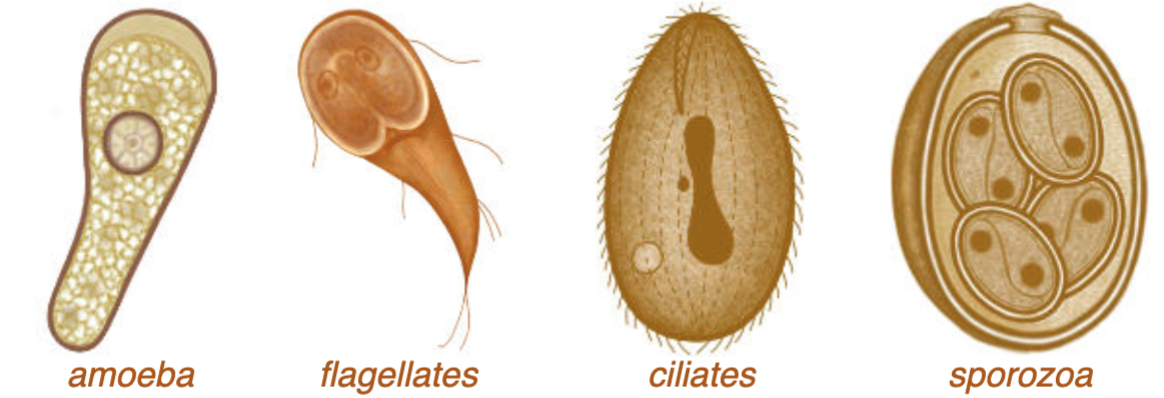

Classified into four groups

Sarcodina (ameba)

Ex. Entamoeba

Mastigophora (flagellates)

ex. Giardia, leishmania

Ciliophora (ciliates)

ex. Balantidium

Sporozoa organism whose adult stage is not motile (can't move)

Ex. plasmodium, cryptosporidium

Protozoan Classes

Amoebae

Use pseudopodia to creep or crawl over solid substrates

Similar to human macrophages

Flagellates

Use elongate flagella: undulate to propel the cell through liquid environments

Flagella: whip-like extensions of the cell membrane with an inner core of microtubules arranged in a specific 2+9 configuration (similar to human spermatozoa)

Ciliates

Use numerous small cilia which undulate (move up and down) in waves allowing the ell to swim in fluids

Cilia: “hair-like” extensions of cell membrane similar to flagella but with interconnecting basal element facilitating synchronous movement (similar to human bronchial epithelial cells)

Sporozoa

“Spore-formers” form non-motile spores as transmission stages

Many pre-spore stages move using tiny undulating ridges or waves in the cell membrane imparting a forward gliding motion

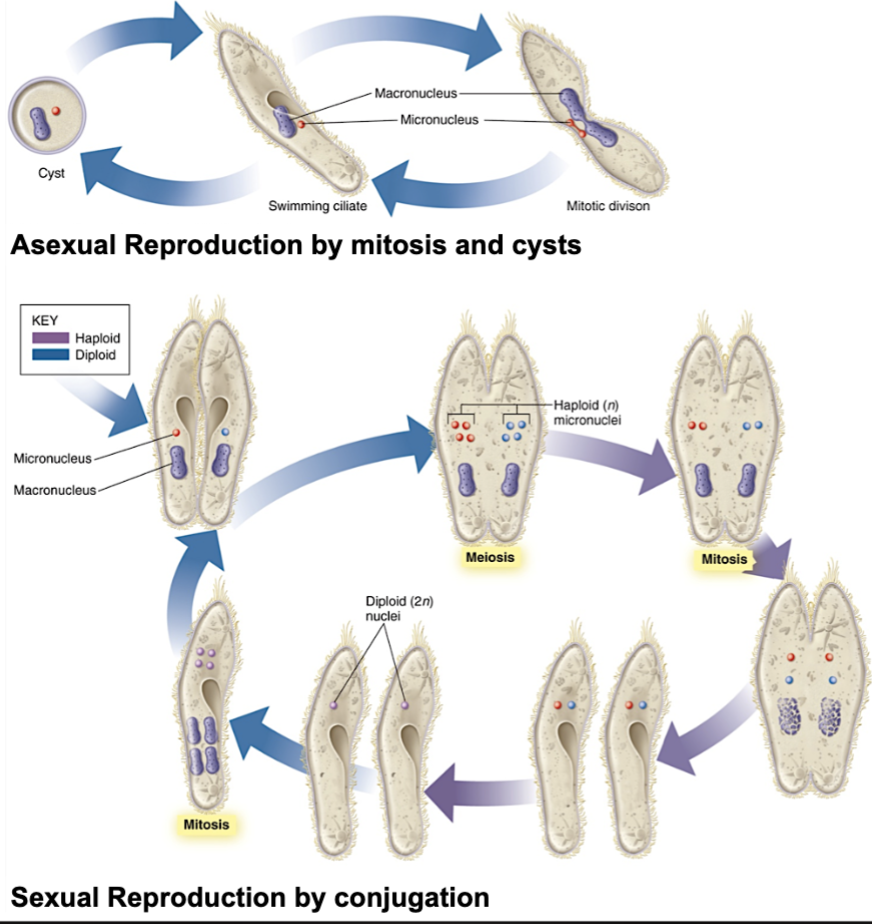

Protozoan Life Cycles

Short generation times

Enormous reproductive potential → rapidly causes acute disease

Increased chances for mutation → changes in virulence, drug susceptibility and other characteris

Asexual or sexual reproduction

Asexual (in intermediate hosts)

Budding: outgrowth of a mature cell grows and becomes a new daughter cell

Binary fission: one nuclear division gives rise to two daughter cells (closest to mitosis)

Schizogony: “multiple fission” – nucleus divides repeatedly, allowing one cell to give rise to many daughter cells

Sexual (in definite hosts)

Conjugation: cells that java undergone a reduction division fuse, exchange haploid micronuclei, and separate – each gives ride to two daughter cells

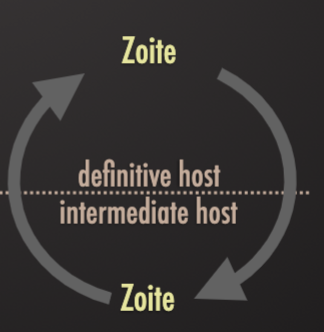

Some protozoa have complex life cy;es requiring two different host species: others require only a single host to complete the life cycle

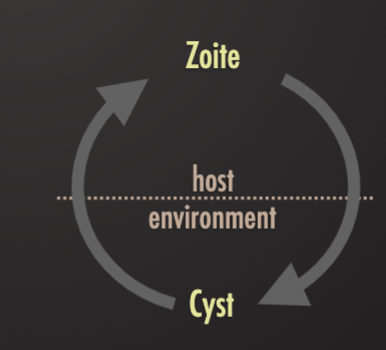

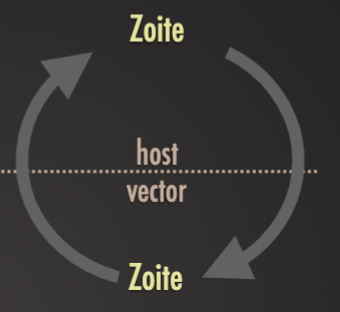

Protozoan Life Cycles

Protozoan Terminology

Trophozoite (“animals that feeds”)

Active, feeding, multiplying stage of most protozoa

Stage usually associated with pathogenesis

May be found intracellularly (within host cells) or extracellularly (in hollow organs, body fluids or interstitial spaces between cells)

Not very resistant to external environmental conditions and do not survive long outside of their hosts

Cyst (process: “encystment”)

Formed by only some protozoa

Can contain one or more infective forms

Multiplication can occurs in the cyst of some species, excystation releases more than one organism

Cyst released into the environment (stools) have a protective wall

Oocyst

A hardy, thick-walled stage of the life cycle of some protozoa (sporozoan): stage results from sexual reproduction

Oocysts of some protozoans (sporozoan) are passed in the feces of the host.

Oocysts of plasmodium (causative agent of malaria) developed in the body cavity of the mosquito vector

Protozoan Excystation

Ultrastructural morphology details of an oblong-shaped Giardia sp. Protozoan cyst, revealing the filamentous nature of the cyst wall.

The cyst is undergoing”excystation” with a flagellated trophozoite

Mode of Transmission

Direct Transmission

Of trophozoites through intimate body contact, such as sexual transmission

Ex. trichomonas spp. Flagellates: causes trichomoniasis → infertility in humans and cattle

Fecal-Oral transmission

Environmentally-resistant cyst stages passed in feces of one host and ingested with food/water by another

Ex. entamoeba histolytica, giardia duodenalis

Vector-borne transmission

Trophozoites taken up by blood-sucking arthropods (insect or arachnid) and passed to new hosts when they next feed

Ex. Trypanosoma brucei by tsetse flies to humans (sleeping sickness), cattle, horses, and other livestock . Plasmodium spp. Haemosporidia by mosquitoes to humans (malaria)

Predator-prey transmission

Ziotres encysted within the tissue of prey animal (herbivore) being eaten by a predator (carnivore) which subsequently sheds spores into the environment to be ingested by new pet animals

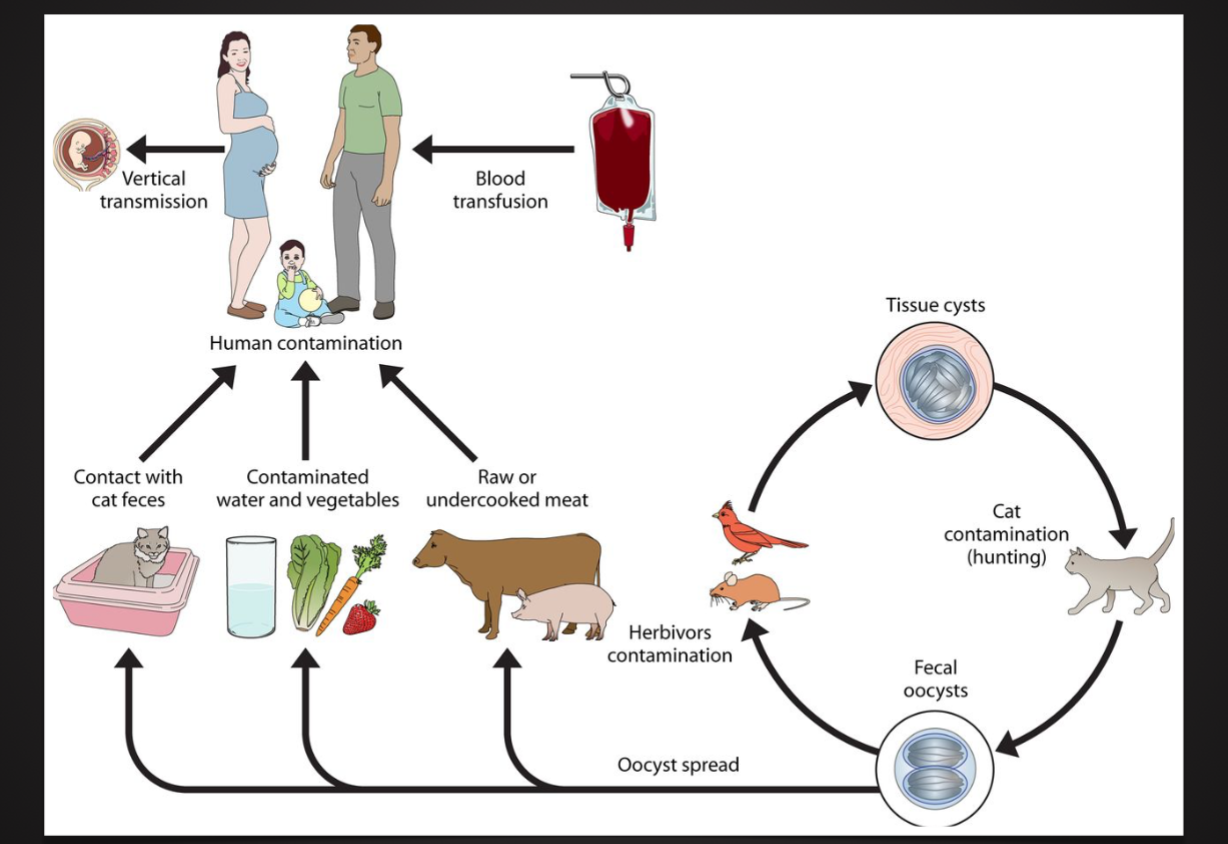

Ex. toxoplasma gondii ingested by cats

Protozoan Escape Mechanisms

Antigenic Masking (and Mimicry?)

Ability of a parasite to escape immune detection by covering itself with host antigens

Blocking of Serum Factors

Some parasites acquire a coating of antigen-antibody complexes or non cytotoxic antibodies that sterically blocks the binding of specific antibody or lymphocytes to a parasite surface antigens

Intracellular Location

The intracellular habitat of some protozoan parasites protects them from the direct effects of the host’s immune response.

By concealing the parasites antigens, this strategy also delays detection by the immune system

Antigenic Variation

Some protozoa parasites change their surface antigens during the course of an infection

Parasites carrying the new antigens escape the immune response to the original antigens

Immunosuppression

Parasitic protozoan infections generally produce some degree of host immunosuppression

This reduced immune response may delay detection of antigenic variants

Can reduce the ability of the immune system to inhibit the growth of and/or to kill the parasites

Protozoan Pathogenesis

Cellular ,Tissue and Organ Damage

Extracellular or intracellular parasites that destroy cells while feeding can lead to organ dysfunction and serious or life-threatening consequences

Toxic protozoal products

Toxins associated with some protozoa (plasmodium) can cause fever and chills (can occur cyclically)

Interference with host function

Some parasites that inhabit the small intestine can significantly interfere with digestion and absorption and affect the nutritional status of the host

Delayed-type hypersensitivity

Pathology as a consequence of immune response mediated by antigen-specific effect T cells

Immunosuppression

Host is susceptible to secondary infection (by other pathogens)

Toxoplasma Gondii

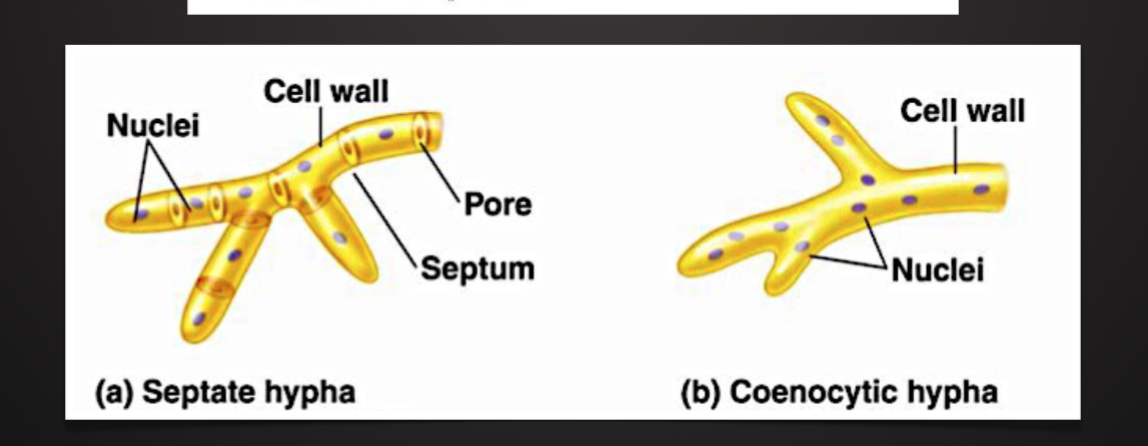

Fungi 02/27/24

Pathogenesis of Infection: Fungi Tuesday 02/27/24

Some Terminology

Mycoses (singular = mycosis);

Diseases of warm-blooded animals caused by fungi

Medical Mycology

Study of fungi as animal and human pathogens

Fungal Pathogens

Eukaryotic organisms:

separate from plants and animals

Genetically more closely related to animals than plants

About 1.5 million different species exist

Only 300 species are pathogenic

Many pathogenic fungi are microorganisms

Most are multicellular (molds), but some are unicellular (yeasts)

Dimorphic fungi can exist as molds or yeasts

Heterotropic

Incapable of producing food

Fungi feed by extracellular digestion

Saprobic

Live of dead organic matter

Help to cycle nutrients (decomposition)

Mutualistic

Some are in symbiosis with plant roots

Parasitic

Live on living organism, cause disease of the host

Mostly asecual or secual reporduction and dispersion by spores

In contrast: yeast reproduce by budding or binary fission

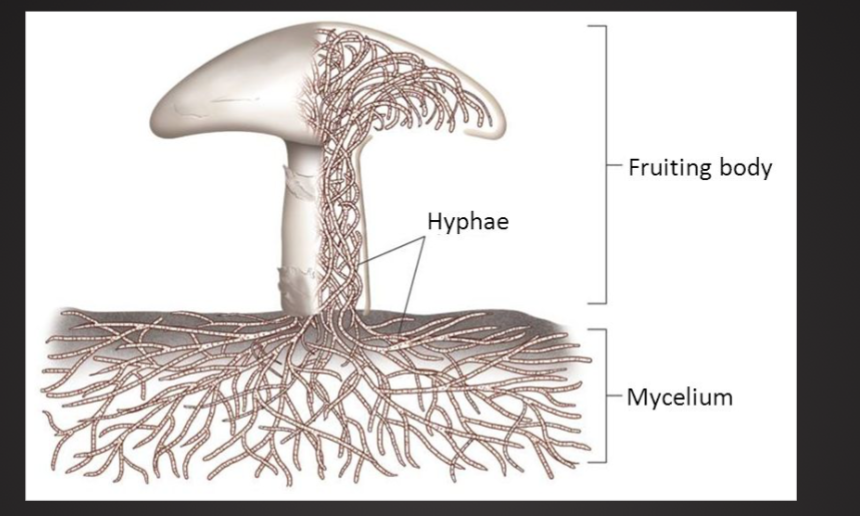

Have rigid cell wall (glucans and chitin)

Basic Fungal Structure

Fungal Cell Wall

Yeast (Unicellular Fungi)

Yeast genus Candida

Most clinically relevant fungal group

Has multiple species which cause disease in humans and animals

Yeast genus Cryptococcus

Causes opportunistic infections (meningitis, pneumonia)

Has a few species which cause disease in humans and animals (most common in cats but also in dogs, cattle, horses, sheep, goats, birds and wild animals)

Molds (multicellular fungi)

Molds are extremely diverse group of organism, the vast majority of which are non-pathogenic

Has two major pathologic groups:

Genus aspergillus

Order mucorales

Molds and their pores are found in soil and decaying vegetation throughout the world

Both can cause rhino-sinustitis and various forms of pulmonary infections in immunocompromised humans and animals

Dimorphic Fungi

Can exist as either yeast or molds

Typically exist in environment as a mold but shen spores are inhaled they grow in the host as a yeast

Most commonly cause subacute pulmonary infections

Bacteria which Masquerade as Fungi

Nocardia and actinomycetes were originally believed to be fungi, but now are known to be bacteria

Develop filamentous, branching structures

Causes subacute and chronic infections of the lungs, CNS, and soft tissue: most commonly seen in immunocompromised humans and animals

Can be clinically indistinguishable from frugal disease

Streptomycin, actinomycin, and streptothricin and are all medically important antibiotics isolated from actinomycetes bacteria

Risk Factors for developing fungal infections

Use of antibiotics

Use of drugs that suppress the immune system

Cancer chemotherapy drugs

Corticosteroids

Anti-organ rejection drugs (ex. Azathioprine, methotrexate and cyclosporine)

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (treat rheumatoid arthritis and related disorder

Disorders

AIDS

Burns, if extensive

Diabetes

Hodgkin lymphoma ar other lymphomas, leukemia

Environmental Factors

Warm, moist areas of the body (mouth, vagina)

Sweaty clothes and shoes enhance fungus growth on the skin

Indwelling catheters

Mechanical ventilation

Genetic predisposition

Not well understood

General Features of Fungal Infection

Often seen in immunocompromised patients or animals

Exceptions: dimorphic fungi, dermatophytes

Clinical presentation is typically subacute to chronic

Exceptions: candidemia and mucormycosis

Person-toperson transmission doesnt usually occur

Exceptions: dermatophytes and mucocutaneous candida infections

There are no specific symptoms or signs which reliably distinguish fungal infections from bacterial ones

Typical antibiotics are ineffective

Exception: pneumocystis

Classifications of Fungal Infections

Superficial and Cutaneous Mycoses

Involve outermost (stratum corneum) or deeper (keratinized) layers of skin and its appendages (nails or hair)

“Tinea Infections” or “Ringworm”

Usually no inflammation (superficial) allergic or inflammatory response (when deeper)

Primarily caused by dermatophytes

Mucocutaneous Mycoses

Involved skin, eyes, sinuses, oropharynx, external ears, vagina

Candidal Infection

Manifests a superficial mucocutaneous disease to invasive disease with dissemination

Oral candidiasis (thrush) and esophageal candidiasis are characterized by white patches on the tongue or mucosal surfaces (can be removed by scraping).

Vulvovaginitis is seen in the settings or oral contraceptive use, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy , and antibiotic therapy, it manifests with vaginal discharge and vulvar edema and pruritus

Subcutaneous Mycoses

Often caused by saprophytes from soil or vegetation

Many are confined to tropical and subtropical regions

Involve subcutaneous tissues, muscles and fascia

Traumatic inoculation

Localized (often chronic) infection

Treatment usually involves use of antifungal agents and/or surgical excision

Treatment of some serious subcutaneous mycoses reamines unresolved

Systemic (Deep) Mycoses

Diseases that occur deep within the tissues, involving vital organs and/or the nervous system

Entry into the body is usually through inhalation of spores or open wounds

Causes by the true pathogenic fungi (usually dimorphic fungi) or opportunistic saprobes

Usually subclinical/ subacute presentation

May be fatal (can also be chronic)

Examples: blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis and histoplasmosis

Symptoms: fever, cough, chest pain, weight loss, fatigue

Allergic Disorders

Mold exposure can trigger several allergic disorders, including:

Asthma

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)

Allergic fungal rhinitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

No established safe limits for indoor mold

Visible mold growth in a home is not reliable measure of exposure

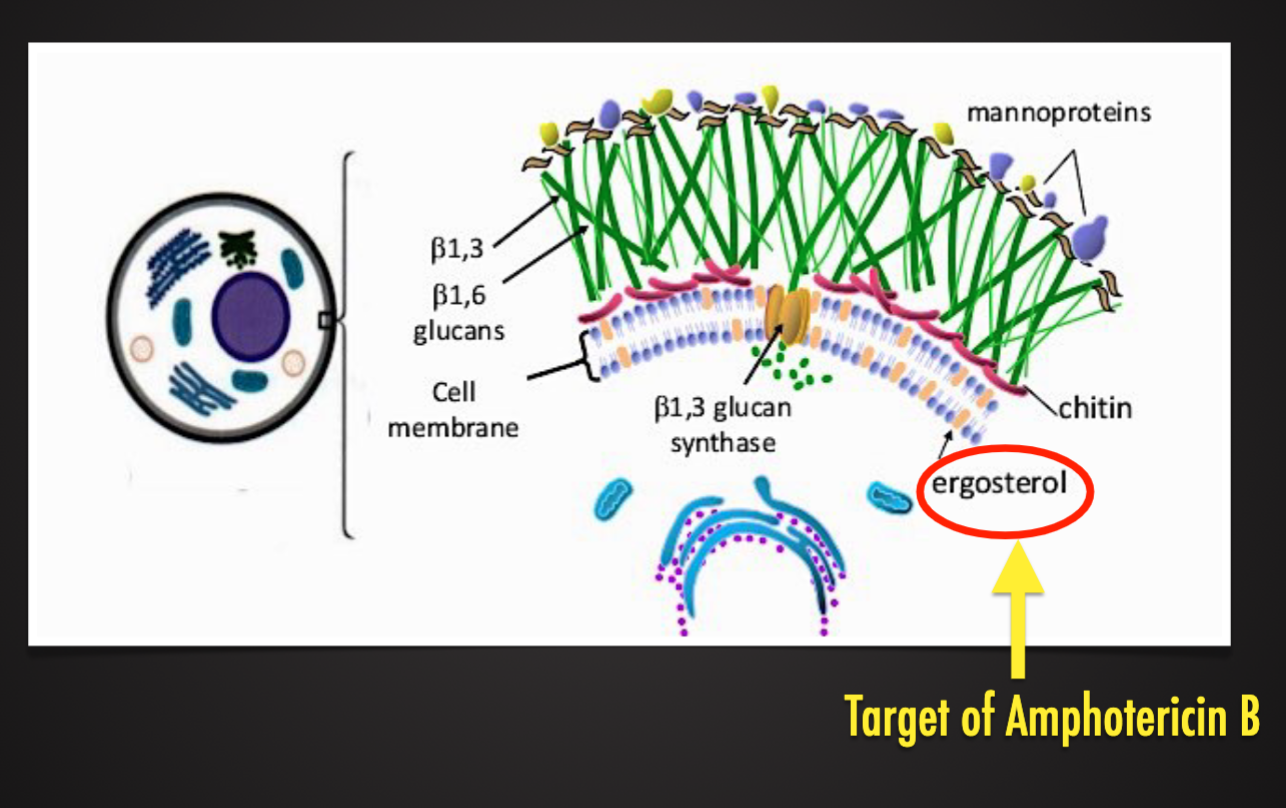

Mycotoxins

Types of Mycotoxins (Fungus poisons)

Mushrooms

50-100 toxic species

Identical to non-toxic ones

Many variety of toxins - different clinical manifestations and severity

Acute liver and renal failure: life-threatening

Aflatoxins

Produced by Aspergillus sp.

At least 14 types

Contaminate corn, soybeans, and peanuts

Acutely, can cause liver failure

Chronic exposure increases risk of hepatocellular carcinoma

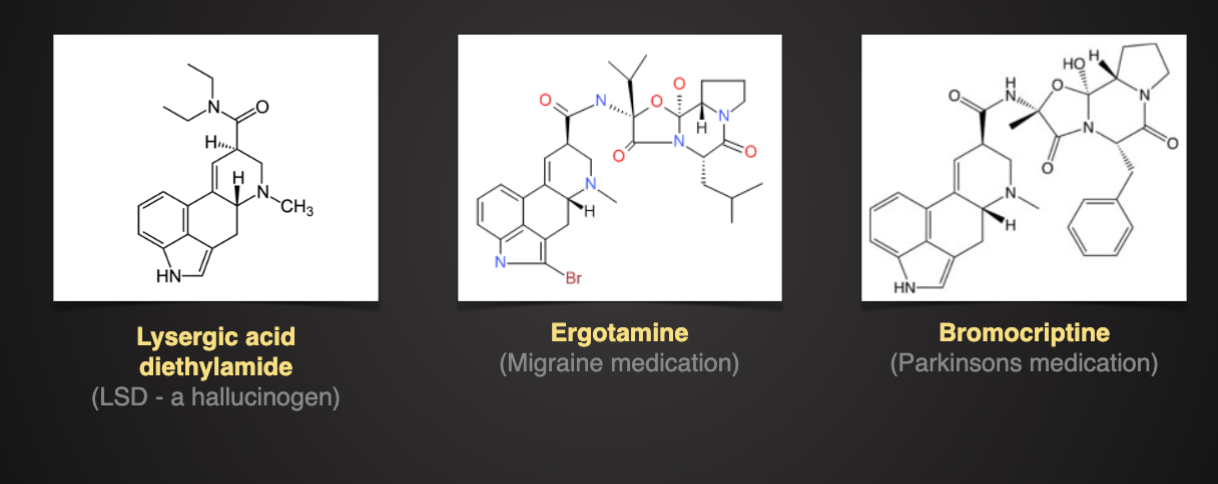

Ergot Alkaloids

Produced by genus, Claviceps

Affected grains: tye, wheat, barely

Ergot alkaloids similar in structure to neurotransmitters, also have vasoconstriction properties.

Ergot Alkaloids

Two forms of ergotism

Acute: seizures, hallucination, mani, vomiting, diarrhea

Chronic- ischemia, and dry gangrene of extremities

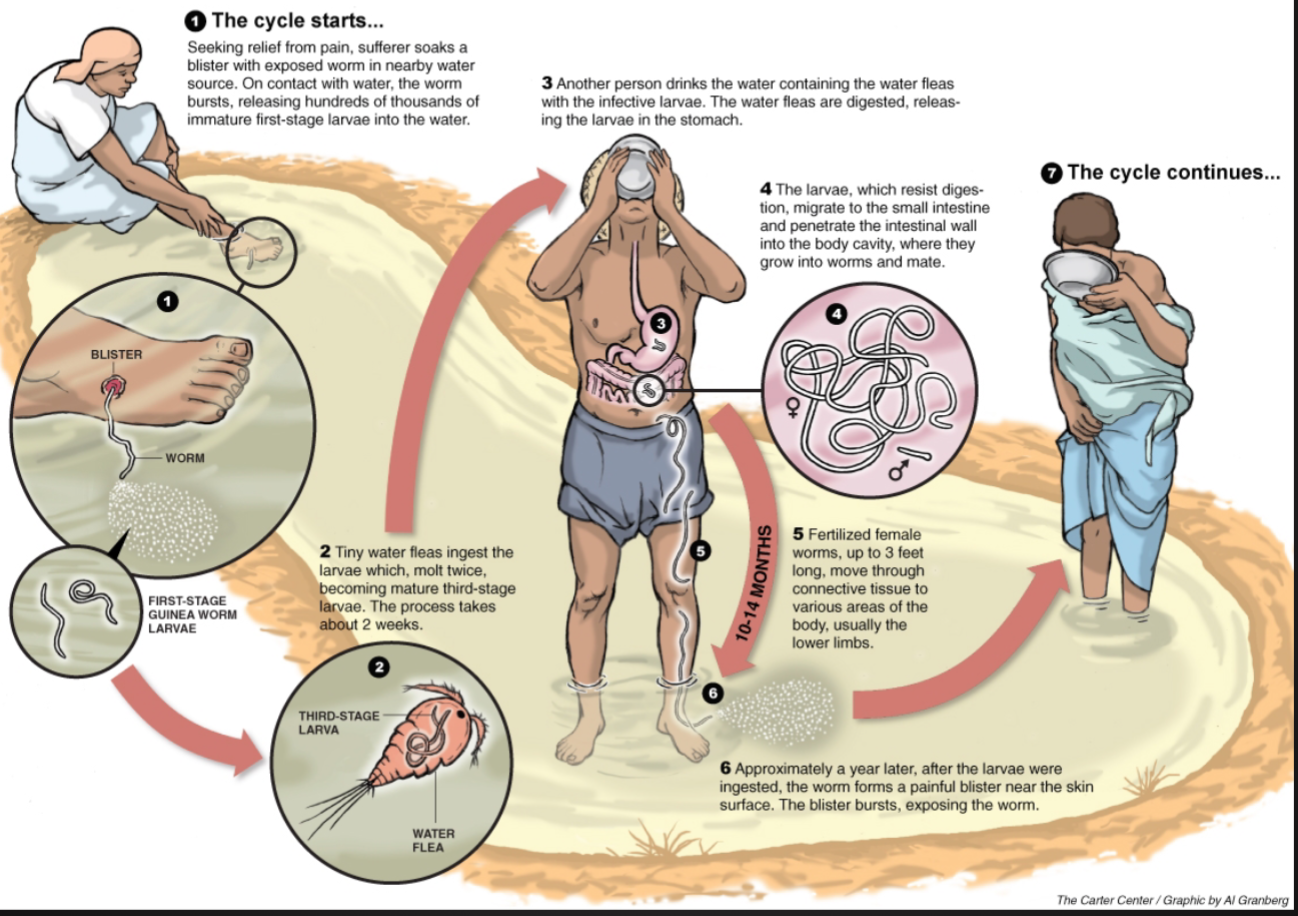

Dracunculus Medinensis – 02.29.24

Dracunculus Medinensis (Guinea Worm)

Parasite: Dracunculus Medinensis - “Little Dragon from Medina”

A nematode: females up to 31” in length, males: ⅙ in length

Disease: Dracunculiasis: Guinea-worm disease (GWD)

One of the older diseases known to humankind

Mentioned in number of historical texts

Sanskrit greek, hebrew (15-16 BS)

Parasite found in egyptian mummies (3000 years old_

Remains endemic in 3 countries: Sudan, Mali, and Ethiopia

Infects humans and domestic animals

Transmitted by drinking water

The Life Cycle of the Guinea Worm

Rod of Asclepius (symbol of medicine)

Greek god Asclepius deity associated with healing and medicine

Symbol continues to be used in modern times, associated with medicine and health care

Historians believe that the extraction of Dracunculus Medinensis (“the fiery serpent”) on a stick led to the symbolism behind the Rod of Asclepius

Caduceus (Staff of Mercury and Hermes)

The caduceus is recognized symbol of commerce and negotiation

Mistakenly used as the symbol of medicine in the united states

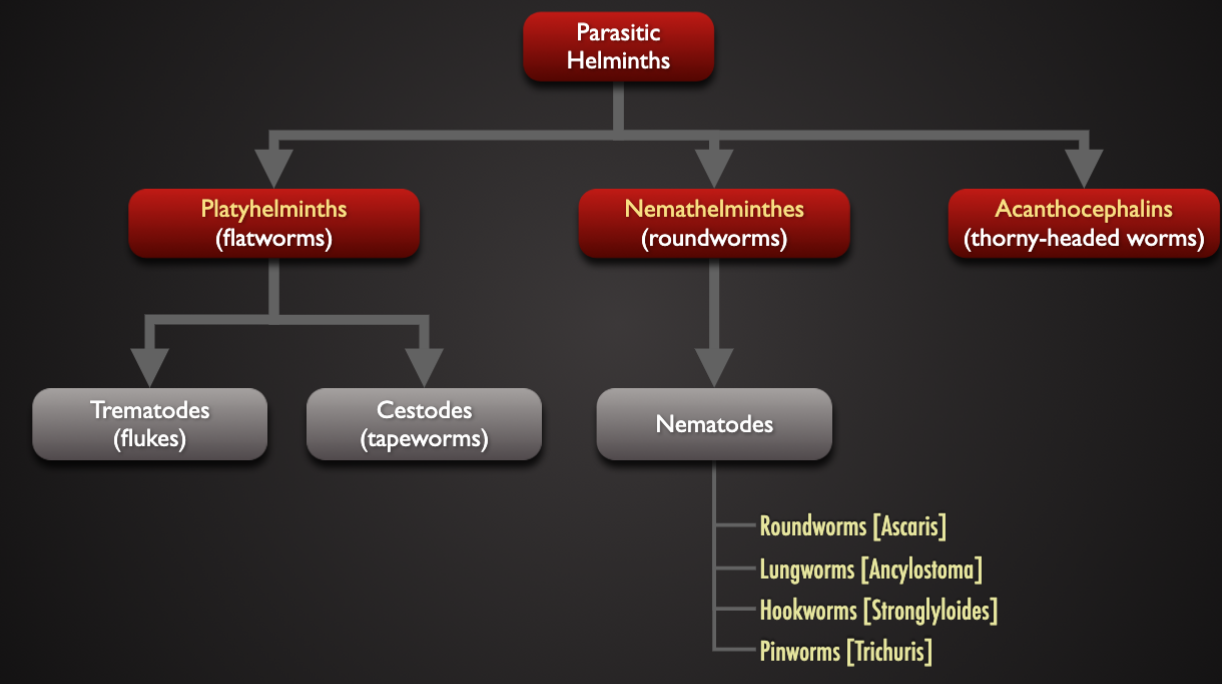

Introduction to Helminths (Parasitic Worms)

Helminths (Parasitic Worms)

Eukaryotic organism, invertebrates

Relatively large (>1 mm long) some are very large (>1 m long)

Have well-developed organ systems and most are active feeder

The body is either flattened and covered with plasma membrane (flatworms) or cylindrical and covered with cuticle (roundworms)

In their adult form, helminths are unable to multiply in humans

Some helminths are hermaphrodites (monoecious) other have separate sexes (dioecious)

Worldwide distribution: infection is most common and serious in poor countries. The distributions by clime, hygiene, diet and explore to vectors

Many infections are asymptomatic, pathogenic manifestations depend on the size, activity, and metabolism of the worms. Immune and inflammatory responses also cause pathology

Production losses due to:

Competition for nutrients

Damage to body systems (gut, liver, can lead to death)

Animal welfare: companion animals - food animals

Public health: zoonotic infections

Taxonomy of Helminths

Characteristic of Helminths

Trematode (flukes) | Cestode (tapeworm) | Nematode (roundworm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Appearance | leaf-life | tape-like | worm-like |

cross-section | Flattened | flattened | cylindrical |

Body cavity | absent | absent | fluid-filled |

gut | Blind sack | absent | true-gut |

Life cycle | indirect | indirect | Direct and indirect |

reproduction | monoecious | monoecious | dioecious |

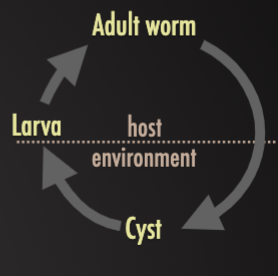

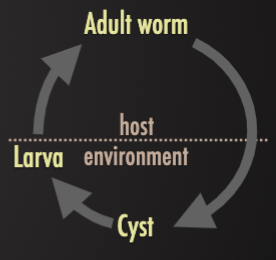

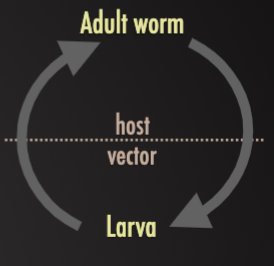

Host Types

Definitive Host

Host where adult stages develop

Intermediate Host

Host where immature stages develop to produce usually ineffective stages of it without reaching to maturity

Paratenic Host

Immature stage retained but no parasite development

Transmission Route

Fecal-Oral

Eggs or larvae passed in the feces of one host and ingested with food/water by another

Ex. ( Ingestion of Trichuris eggs leads directly to guy infections in humans.) (Ingestion of Ascaris eggs and Strongyloides larvae leads to a pulmonary migration phase before gut infection in humans)

Transdermal

Infective larvae in the soil (geo-helminths) actively penetrate the skin and migrating through the tissues to the guy where adults develop and produce eggs that are released in host feces

Ex. larval hookworms penetrate the skin, undergoing pulmonary migration and infecting the guy where they feed on blood causing iron-deficiency anemia in humans

Vector-borne

Larval stages taken up by blood-sucking arthropods or undergoing amplification in aquatic molluscs

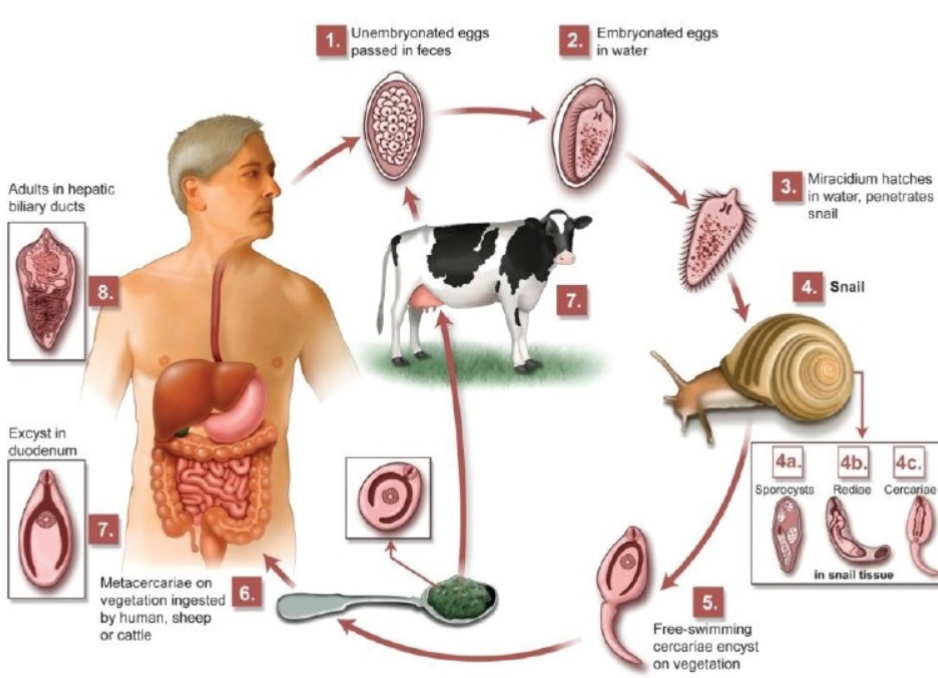

Ex. (1) Onchocerca microfilariae ingested by blackflies and injected into new human hosts, (2) Schistosoma eggs release miracidia to infect snails where they multiply and form cercariae which are released to infect new hosts. Cause of “river blindness”

Predator-prey

Encysted larvae within prey animals (vertebrate or invertebrates) being eaten by predators where adult worms develop and produce eggs

Ex. (1) Taenia cysticerci in beef and pork being eaten by humans, (2) Echinococcus hydatid cysts in offal being eaten by dogs.

Survival Strategies

Morphological Adaptations

Degeneration of organs

Organs of locomotion

Tropic organs

Nervous system and sense organs

Attainment of new organs

Body shape (adapted to host environment and migration)

Developed of protective covering (cuticle is resistant to digestive enzymes)

Development of adhesive organs (sucks, hooks, jaws, secretory glands, acetabulum)

Physiological Adaptations

Secretion of anti-enzymes and mucous

Facultative anaerobic respiration

Osmotic pressure adaptability

Chemotaxis

Hypobiosis

Critical hatching conditions

Periparturient rise

Reproductive

Hermaphroditism

Development of cyst wall

Fecundity

Complexity of life cycle

Avoidance of Host Defence

Acquisition of host molecules to reduce antigenicity

Release substance the depress immune system (ex. Depress lymphocyte function, inactive macrophages, or digest antibodies )

Producing anti-complement factors (to protect their outer layers from lytic attack)

Release large amounts of antigenic material - antigen overload ( to divert immune responses, locally exhaust immune potential)

Induce a form of immune tolerance (infections acquired in life- before or shortly after birth)

Pathogenesis of Helminth Infections

Direction damage from worm activity

Block of internal organs

Ex. Gi transit, blood flow through organs or lymph flow affected by worm size, migration and granuloma formation

Pressure exerted by growing parasites

Ex. large fluid-like cyst in the liver, brain, lungs or body cavity

Physical Damage

Ex. tissue necrosis, feeding by worms, damage during migration

Chemical damage

Ex. release of excretory-secretory materials, release of enzymes and factors such as anticoagulants)

Nutritional impact in under-nutritioned individuals or animals

Infect Damage from Host Response

Hypersensitivity-base inflammatory changes

Ex. contribute to lymphatic blockage associated with filarial infections)

Local allergic responses

Eosinophilia, edema, and joint pain

Structural changes

Ex. villous atrophy, mucosa permeability changes

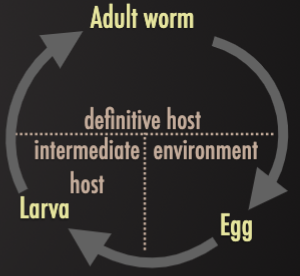

Simple (direct) Life Cycle: Enterobius Vermicularis (pinworm)

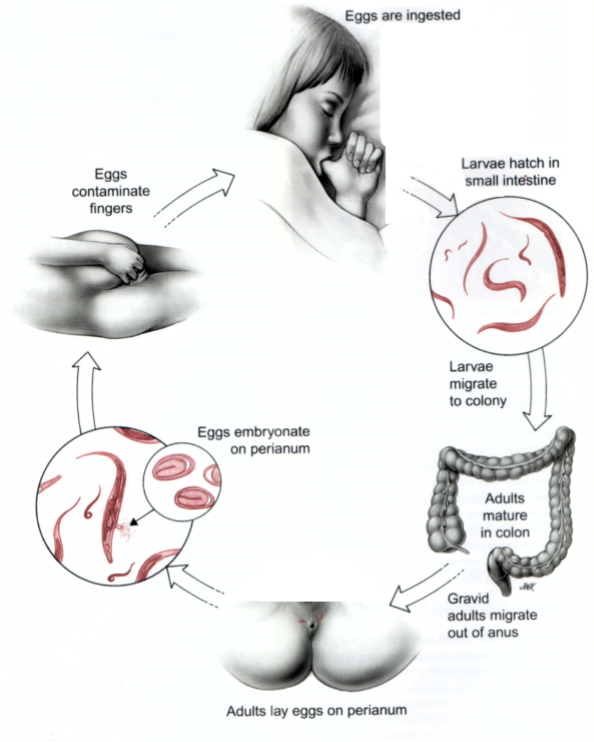

Complex Life Cycle: Paragonium westermani (Lung Fluke)

Complex Life Cycle: Fasciola Hepatica (Liver Fluker)

Prion Disease 03/05/24

Prion Diseases (transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs))

Humans

Kuru (“to shake”)

Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease (CJD)

Fatal Familial Insomnia (FF)

Gerstmann Straussler Syndrome (GSS)

Cattle

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (Mad Cow Disease) (BSE)

Sheep/Goats

Scrapie

Deer/ELK

Chronic Wasting Disease (CDW)

Characteristics of TSEs (Prions Disease)

Spongiform (brain vacuolation

Neuronal loss, gliosis and astocytosis

Atrophy of brain tissue

Accumulation of misfolded prion plaques

Different Prions affect different parts of the brain

Cerebral cortex

Symptoms: loss of memory, mental acuity, visual impairment (CJD)

Thalamus

Damage leads to insomnia (FFI)

Cerebellum

Damage leads to body coordination movement problems and hard to walk (kuru, GSS)

Brain stem

Mad cow disease (BSE) – brain stem is affected

Characteristics of Infection

Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

widespread neuronal loss

Loss of motor control

Dementia

Paralysis

Kuru

Identified by epidemiology in Papua New Guinea based on anthropological research by Robert and Louise Glasse in 1950’s

1% of the Fore tribe was afflicted: most women, some children, few adult males

Symptoms: headache, joint,6-12 weeks later →difficult walking, death within 1-2 years

1910-1920

Evidence lead Glasse to suggest that endocannibalism was associated with disease

Carlton Gadjusek did research and proved Kuru killed patients

From Kuru to Scrapie

Animals needed to study TSEs

Scrape disease in sheep is similar to kuru with symptoms and etiology

Scrapie can be transmitted to hamster and mice, not kuru

Mice infected with scrape were the first good animal model

Infectious agent purified 5000 fold:

Nuclease resistant

UV and heat resistant

Sensitive to protease (only at high levels) and protein denaturants

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) “mad cow disease”

1970: hydrocarbon-solvent extraction of meat and bone meal for cattle feed was abandoned in Britain

1986: 7000 infected cows. BSE became reportable, epidemiology suggested a prion ideas, and meat and bond meal use was abandoned

BSE incubation period is 5 years: 1 mill cows were infected

1989: human consumption of bovine CNS tissue (though to have highest prion concentration) banned based on fears of transmission to humans

1996: new type of CJD appeared in Britain and France on young patients and different neuropathology. Linked with consumption of BSE-contaminated beef

Introduction to Prions

“Pree-ons”

Shortened for “proteinaceous infectious particle”

Causes transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) among other disease

No treatment available to halt progression of TSEs. Treatment in humans is aimed at alleviating symptoms and making patient comfortable

TSEs are ALWAYS FATAL

Basic Structure

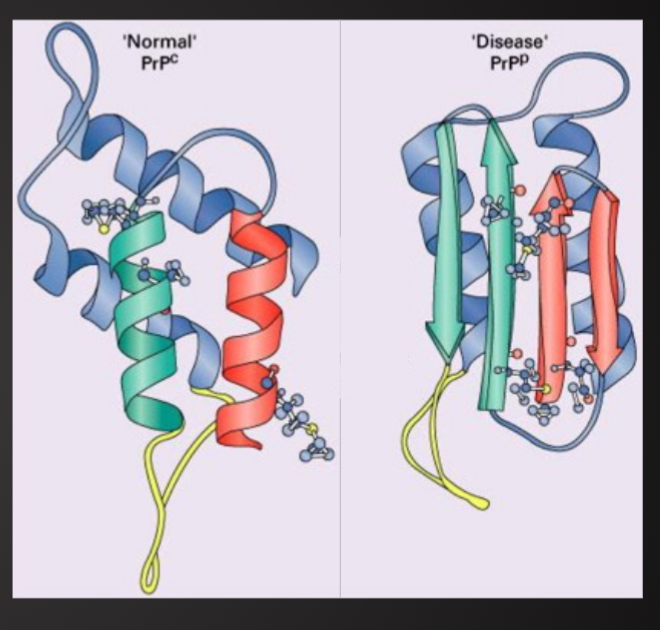

Normal prions (PrPC ) – common in brain cells

Contains 200-250 amino acids twisted into coils(helices) with tails of more amino acids

The mutated and infectious form (PrPSC )

Built from same amino acids but take different shape

100x smaller than known virus

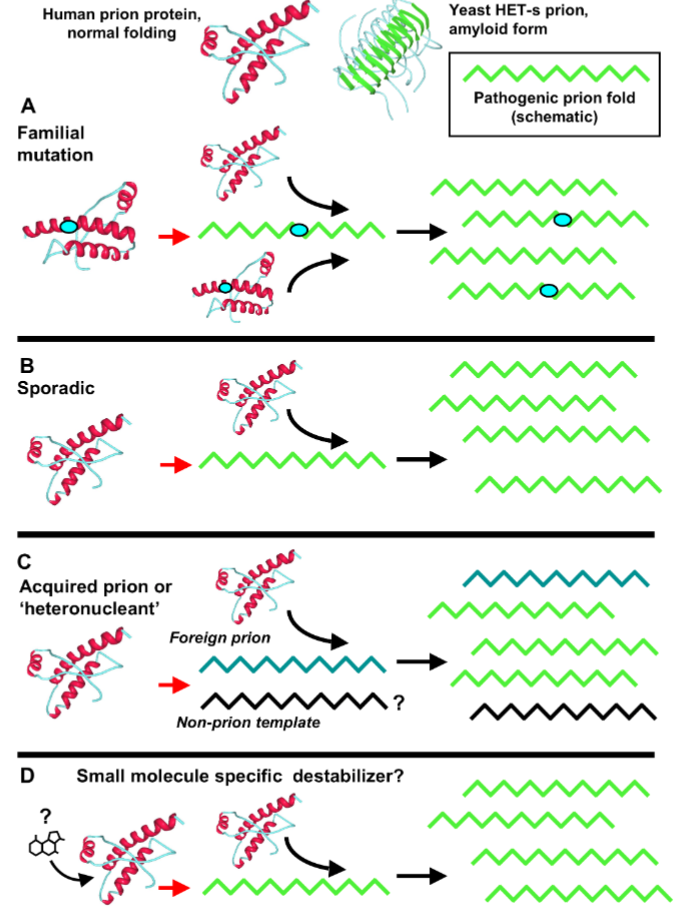

Types of Prion Diseases (TSEs)

Sporadic

Occur with no prion protein mutation

Most TSEs are sporadic

Cause unknown

Infected 1-2 mill people late in life

Infectious

Ex. Kuru,, BSE (mad cow disease), Scrapie

Consumption of infected material

Iatrogenic spread (organ transplant, esp. corneaL been operated with surgical instruments used on a CJD patient)

Familial / Hereditary

Due to autosomal dominant mutation of PrP

inherited : 10-15% of total human TSE cases

Properties of Infectious Prions (PrPSC )

Resistant to degradation by proteases → leads to accumulation

B-sheet structure of PrPSC have high affinity for other B-sheet structures (in other proteins or other PrPSC) → forms oligomeric, insoluble aggregates that in turn form toxin amyloid plaques → interferes with cell and tissue function and death of cells and tissues

PrPSC are extremely resistant to heat and chemicals

PrPSC are very difficult to decompose biologically

Survive in soil for many years

Prions are not nucleic acids (ex. DNA or RNA0

How do infectious prions propagate>

During oligomerization the prions corrupt the native form of the protein into a transmissible disease conformation

Formation of Infectious Prions PrPSC

Intro to Immunology and Innate Immune System 03.12.24

Basic Concepts of Immunology

Immunology is the study of the body's defense against infection. We are continually exposed to microorganisms, many of which cause disease, and yet become ill only rarely

How does the body defend itself?

When infection does occur, how does the body eliminate the invader and cure itself?

Why do we develop long-lasting immunity to many infectious diseases

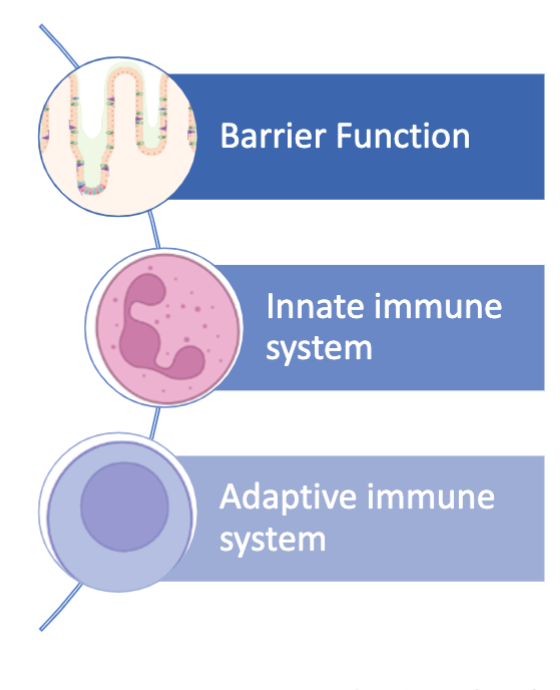

Components of the Immune System

Basic defense system of the body

Composed by specialized cell types and organized structures that coordinate defense mechanisms

Protects from harmful pathogens and disease

Prevent and limit infection

When unsuccessful in curving the infection disease arise

History of Immunology

Edward Jenner, developed the first vaccine against smallpox (18th century). Develop the first vaccine by infecting a patient with cowpox and demonstrating that the patient became immune to smallpox.

Louis Pasteur, France, 19th century: Demonstrated that infectious diseases are caused by microorganisms (Germ theory of disease). Pasteur developed the first vaccine against rabies by attenuating the rabies virus, making it less harmful.

Robert Koch, Germany, 19th and early 20th centuries: Koch's work on tuberculosis and anthrax led to significant breakthroughs in our understanding of these diseases and their treatment. Laid the foundation for modern microbiology and the development of antibiotics.

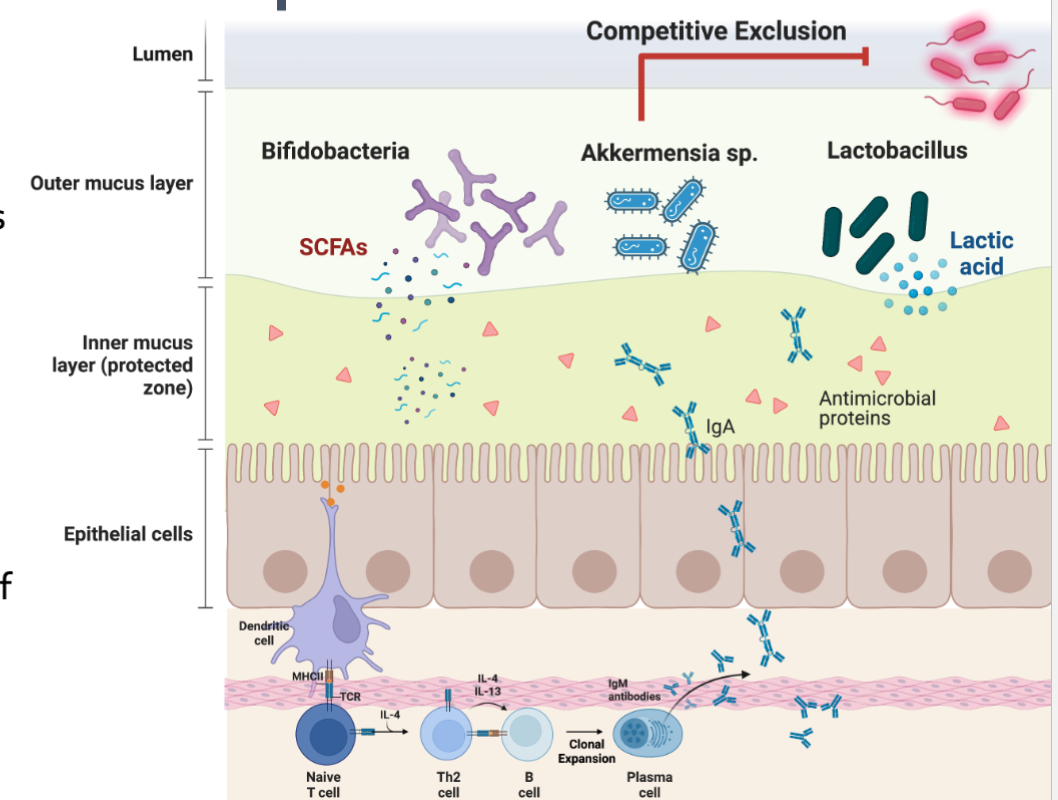

Components of the Mucosal Immune System

Several immune factors function in concert to:

Stratify luminal microbes

Minimize bacterial-epithelial cell contact

Tolerance towards food antigens and commensal microorganism (“oral tolerance”)

Prevent the induction of unnecessary systemic immune responses (“compartmentalization”)

Work in concert to:

Survival and respond accordingly to microbial threats

Maintaining a balance between tolerance and defense mechanisms

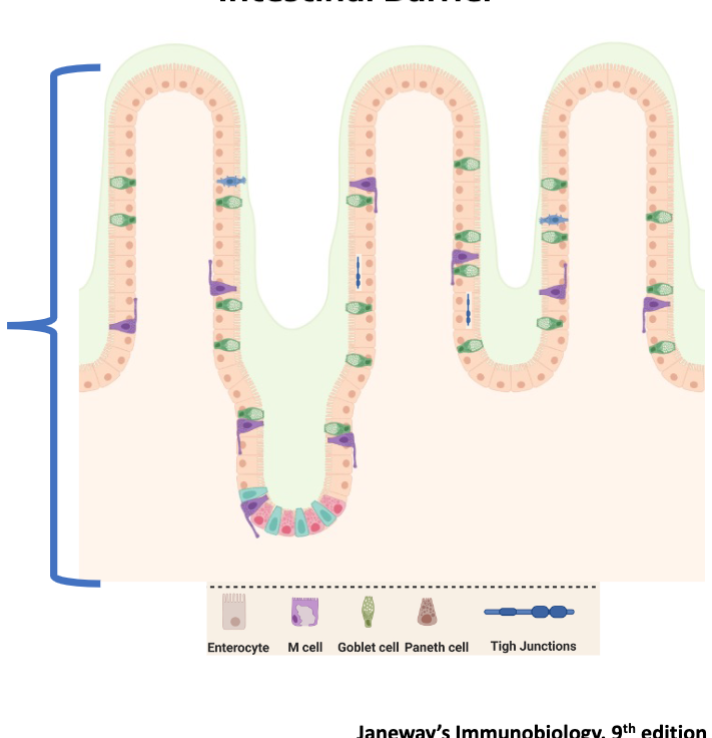

Components of Barrier Function

Intestinal barrier are made up of numerous different cell types

Enterocytes (absorptive)

Goblet cells (mucus-producing)

Paneth cells (found in crypts, produce antimicrobial compounds)

All these cell types develop from a common stem cell at the base of the intestinal crypts

Structure:

One layer of epithelial cells tightly adhered to each other

Epithelial cell shedding

Unidirectional flushing

Inteintal barrier: surface area 25000 sq ft

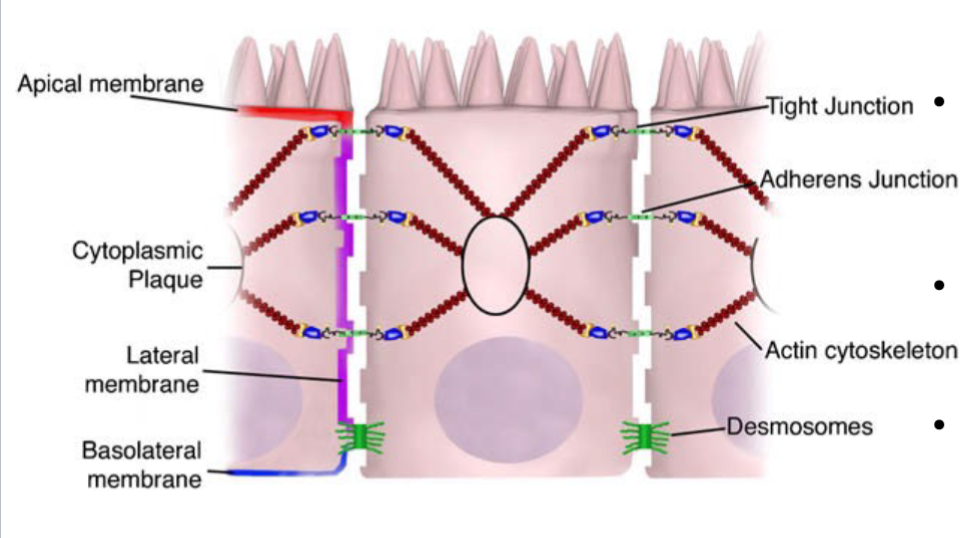

The junctional complex

Transcellular proteins connected through adaptor proteins to the actin cytoskeleton

Important in maintaining cell polarity

Desmosomes are localized dense plaques that are connected to keratin filaments

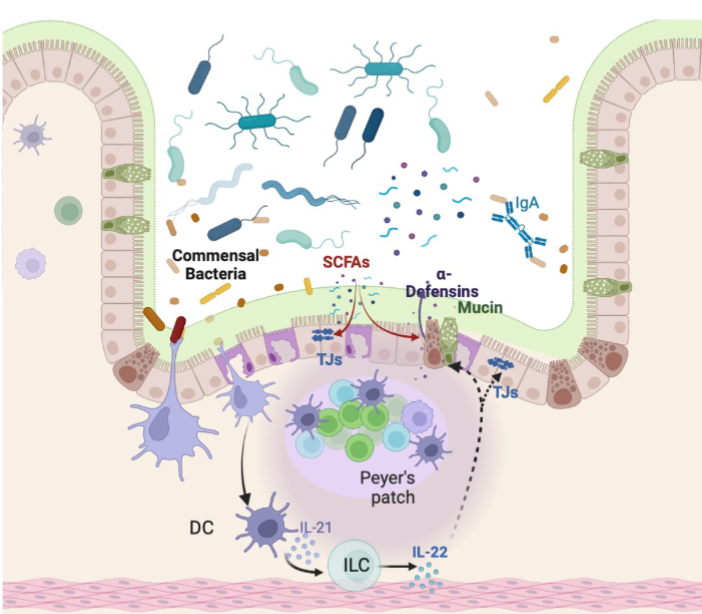

Components of Barrier Function: Mucus Layer

Glycoproteins called mucin by goblet cells

Protein core with several polysaccharide molecules attached

2 layer of Mucin

Outlet layer: colonized by microorganisms

Inner layer: high concentrations of antimicrobial peptides prevents microbial colonization “Killing Zone”

Microbial Sensing of Intestinal Environment

Presence of microorganisms close to epithelial surfaces are recognized by APCs via PRRs

Activated Dcs stimulate IL-22 secretion by innate lymphoid cells

Stimulates epithelial cell proliferation and the secretion of antimicrobial peptides:

Defensins, REGIII, Lactoferricin

AMPs act as lytic enzymes disturbing microbial cell membrane

AMPs disrupt microbial cell membrane by forming pore

Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs)

Several germline-encoded receptors used to recognize different MAMPS

Sensing of MAMPS through the PRRs induces tissue repair and epithelial cell proliferation

Immunological Components of Barrier Function:

Lamina Propria

Loose connective tissue

Contains several immune cells

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

T cells and B cells

Innate lymphoid cells

Other immune mediators (complement, chemokines, cytokines)

Microbiology Research: Pre-NGS Periods

After Louis Pasteur discovered bacteria, medical research focused mainly on their role in causing disease.

The bacteria that reside in and on our bodies were generally regarded as either harmless commensals, or pathogens.

Tools available only allowed us to study these microorganisms one at a time, rather than as communities.

Research focused on the few bacteria that could be grown in vitro. But the majority of microbes that live in our bodies are extremely hard to grow in vitro

Microbiology Research: POST-NGS

Culture-independent techniques (NGS) allow the study of the ecological complexity of the intestinal microbiota and its impact on host physiology.

Have revolutionized the field of microbiology and broadened the lens to explore the functional roles of microbiota on host health and disease.

Intestinal microbiota serves an important role in protecting health, by shaping metabolic and immune function both locally and systemically

Microbial cells in intestine surpass human cells by a factor of 10

Microbial genome is 100 x more extensive than human genome

Intestinal Microbiota role in Health and Disease

The intestinal microbiota have likely evolved under selective pressure to effectively degrade nondigestible plant carbohydrates enhancing the host digestive efficient

Additionally

Metabolic: Vitamin B, K and SCFA

Structural: promote epithelial cell proliferation mucin production

Protective: Competitive exclusion of non-resident bacteria and pathogens

Bidirectional communication between the host and intestinal microbiota via a wide range of metabolites (SCFA, Indoles, BA)

Niche Occupation and Competitive Exclusion

Mucin glycans are nutrients for some bacteria

Establishing a physical barrier (niche Occupation) excluding potential pathogens

Reduce pH by production of SCFAs acetate and lactate

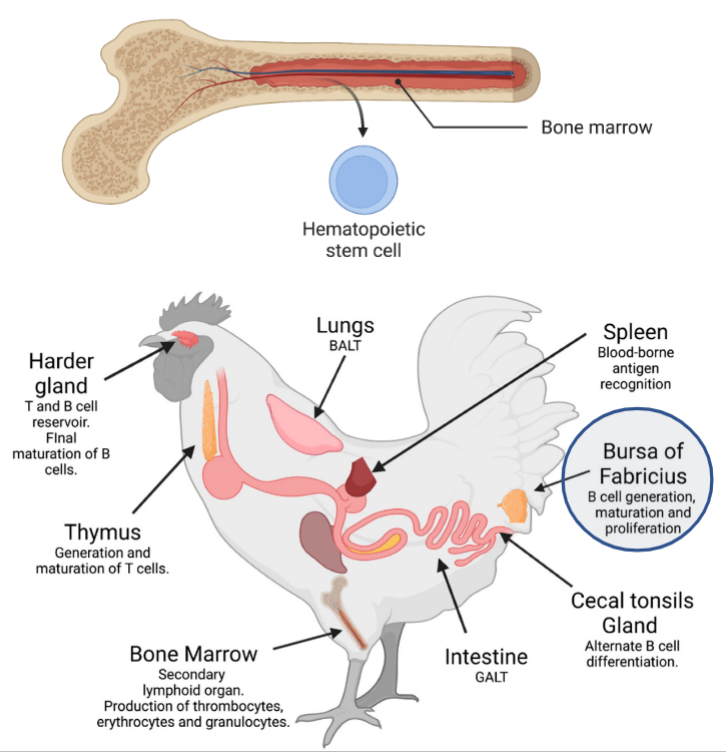

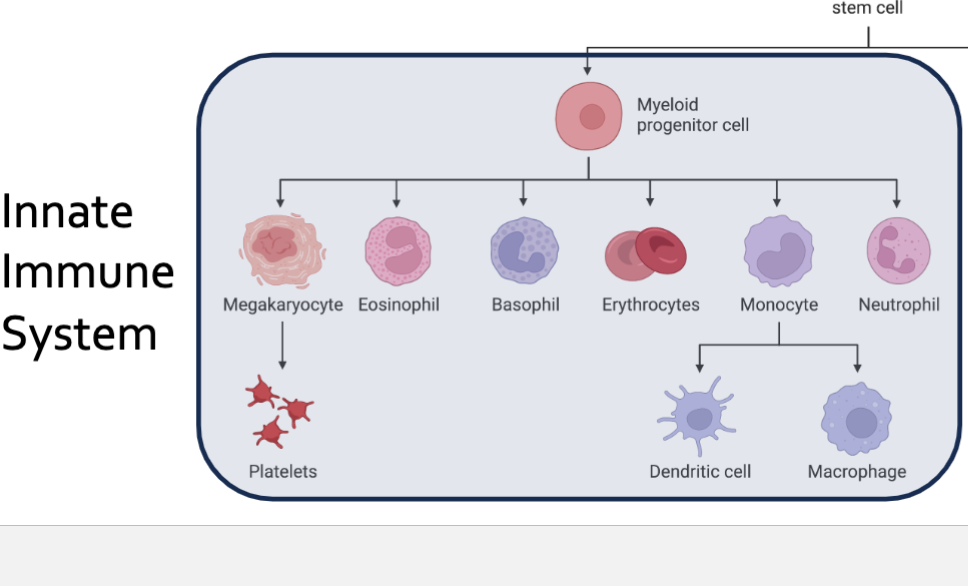

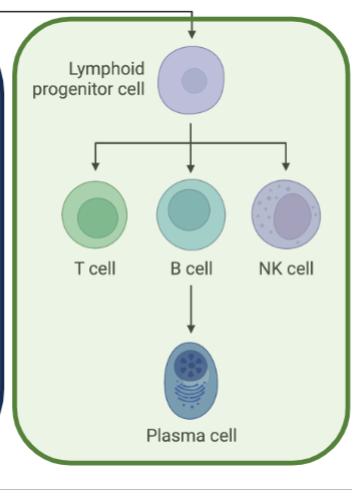

Components of the Immune System

Where do the cells of the immune system come from?

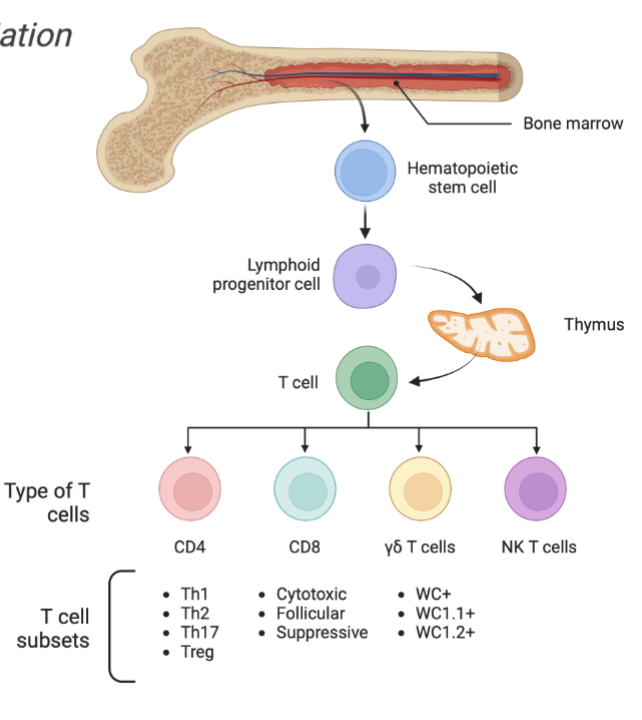

Hematopoiesis in the Bone Marrow

Production of blood cells

Myeloid

Lymphoid

Maturation of Lymphocytes occurs in Central Lymphoid Organs

Bone marrow of animals (Bursa of Fabricius in birds) for B cells

Thymus, for T cells

Immune Cells

Stem cell differentiation from bone marrow

All lymphoid and myeloid cells are derived from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow

Lymphoid and myeloid cells in circulation are collectively referred to as leukocytes or WBCs

Cells are differentiated by appearance and surface markers, clusters of differentiation: CD4, CD8, T cell receptor and C cell receptor

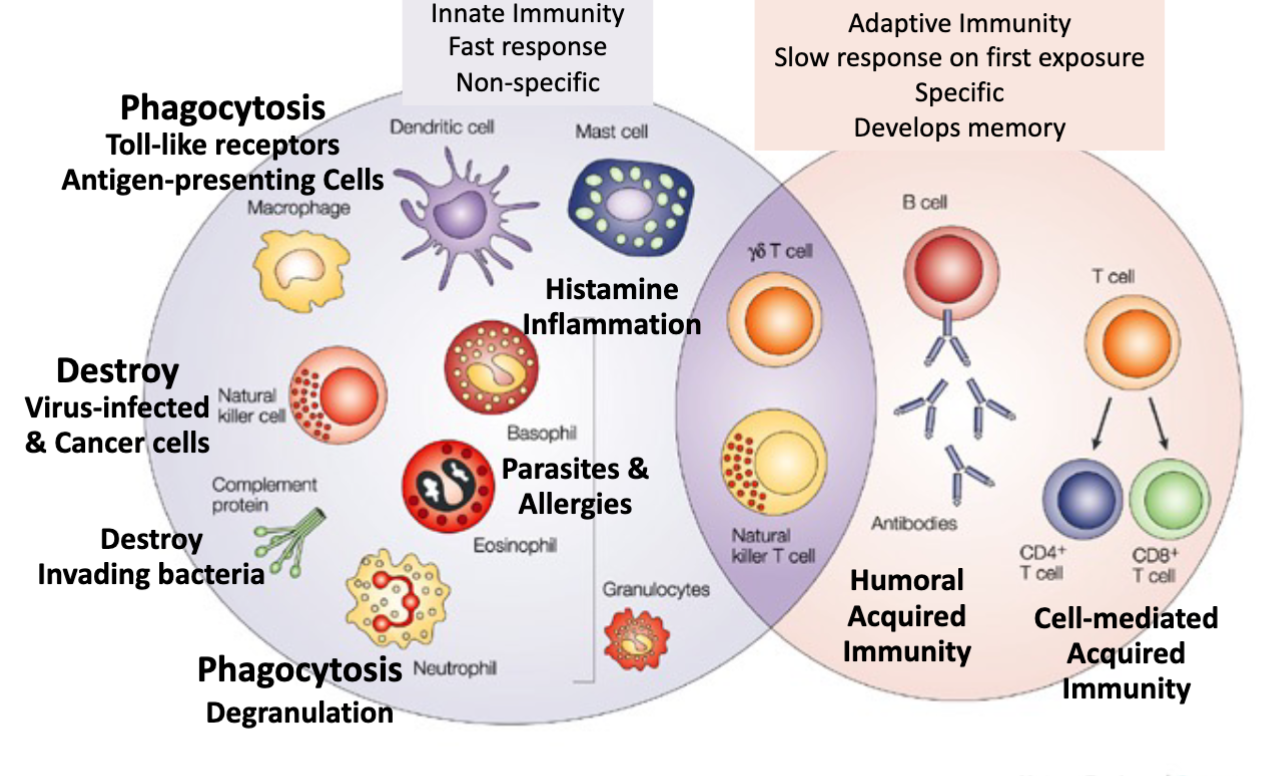

Innate Immunity Faster Response NonSpecific vs Adaptive Immunity Slow response on first exposure specific, develops memory

Innate Immune system Part 2 03.14.24

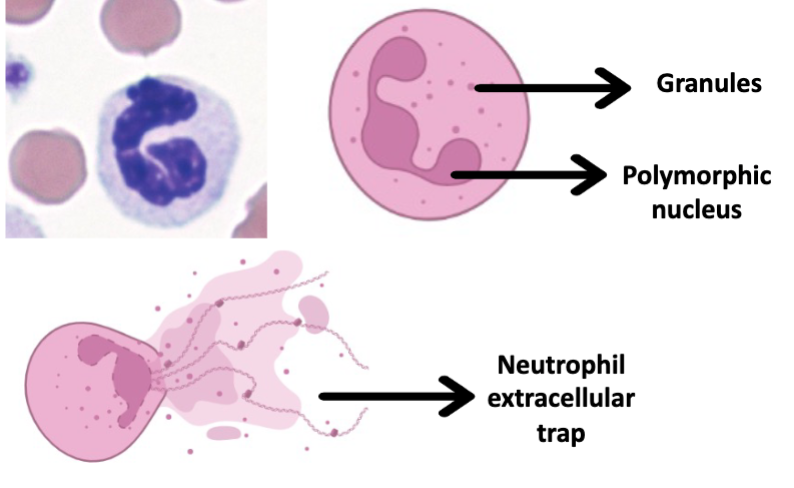

Neutrophils

Components of the immune system innate immunity

50-60% of circulating immune cells

Produce potent antimicrobial toxins, stored in vesicles

First responders to infection

Release mesh like structure composed of cytoskeleton and DNA that traps microorganism

Miltibulate nucleus

Lysosomal granules

Activation of bactericidal mechanism

Phagocytosis and kill

1st white blood cell to infection site

Die and release their contents

Irritate surrounding tissue/recruit other cells

Phagocytosis is improved by opsonization with immunoglobulins

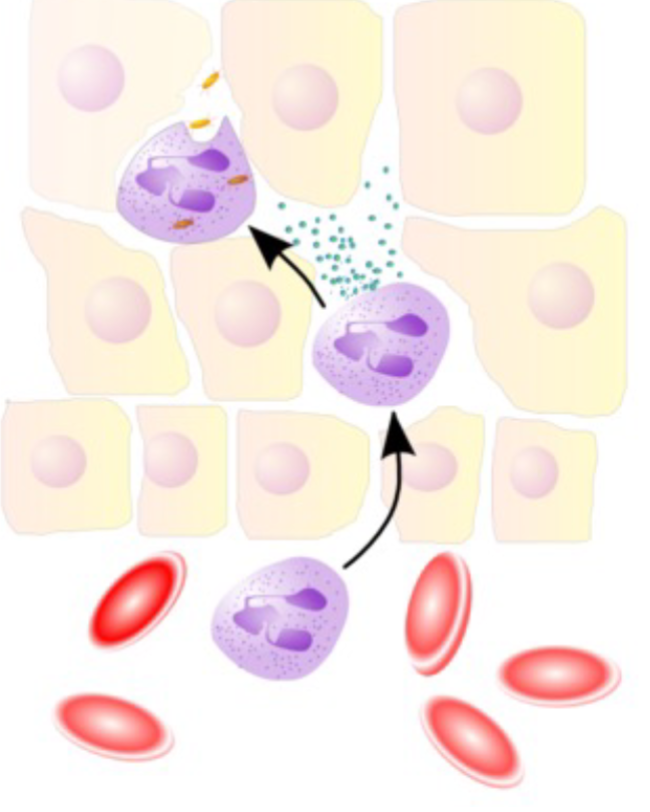

Neutrophils enter site of injury and infiltrate

Release factors important in immune response

Eosinophils and Basophils

Eosinophils

Granules

0.2-3% circulating immune cells

Effective in killing parasites

Basophils

Granules

<0.5% circulating immune cells

Coordinate immune response to parasitic infection

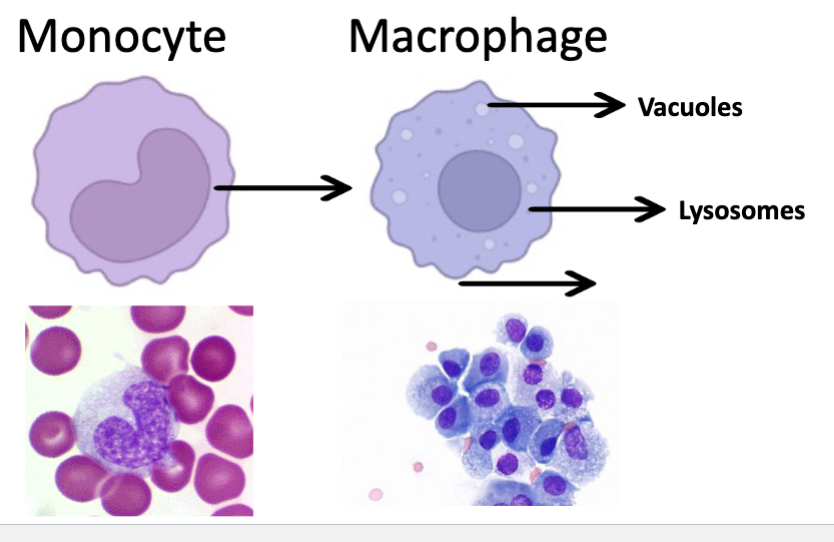

Macrophages and Monocytes

Tissue resident immune cells (sentinel)

Constantly patrolling extracell spaces

Engulf and phagocyte microbes

Coordinate immune activation and promote recruitment of other immune cells

Macrophages

Large cell (10-25 uM diameter)

Main purpose: phagocytosis/kill

Act non-specifically

Chemotactic capability

Release cytokines

Potent phagocytosis when activated by T lymphocytes

Express antigen on surface to T/B cells

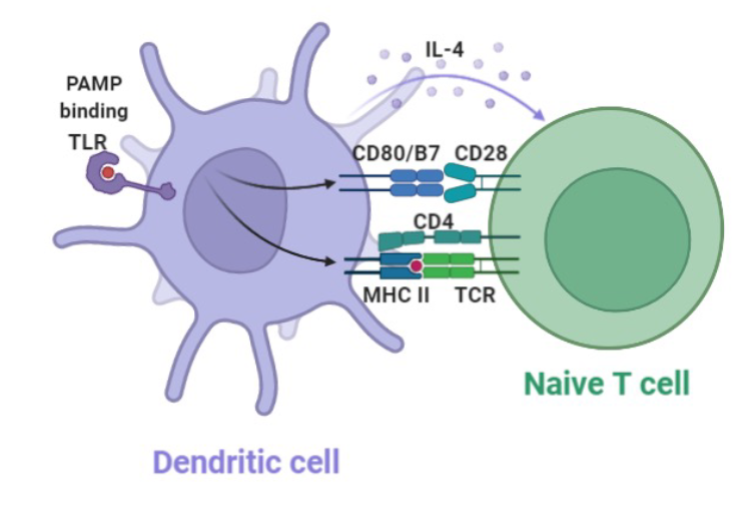

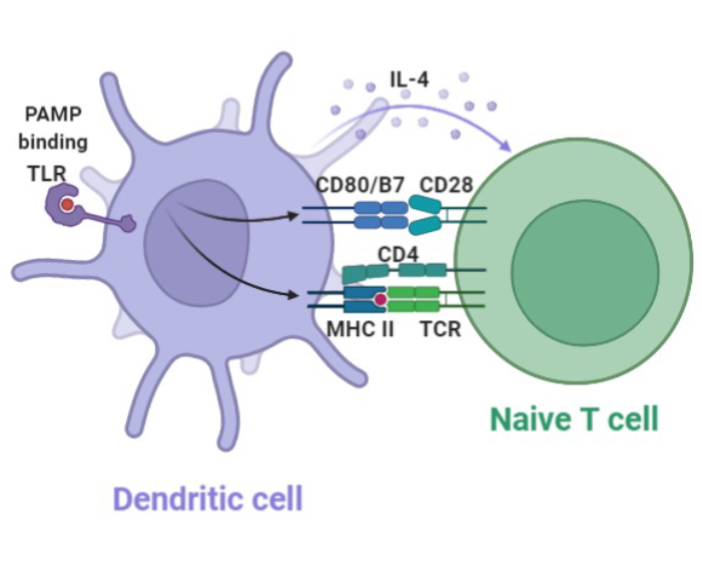

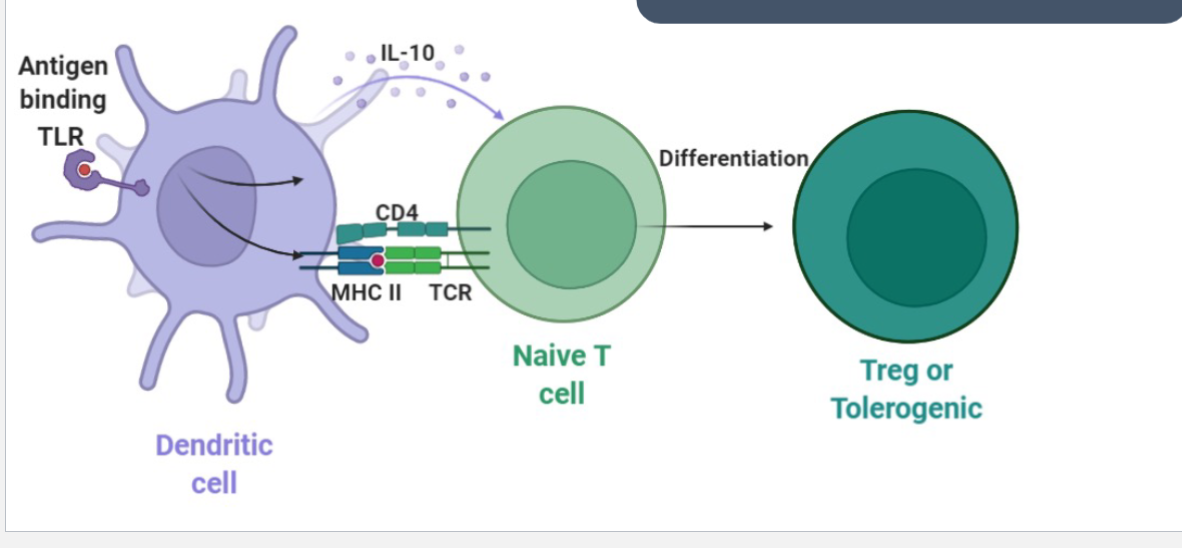

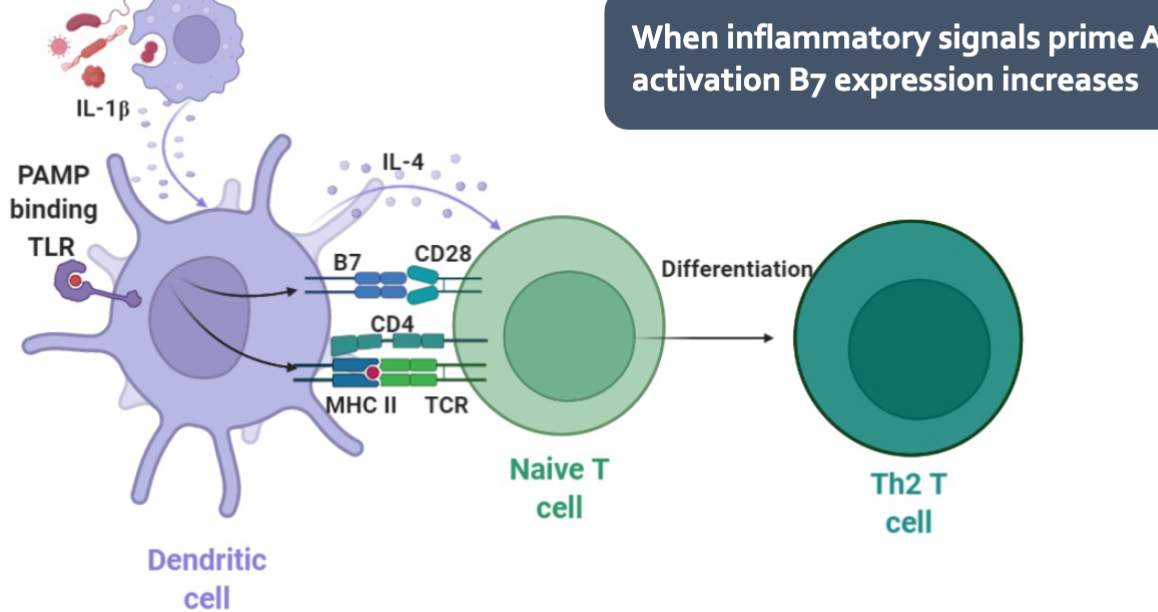

Dendritic Cell

“Professional” antigen presenting cells

Derived from monocytes

Located at barrier sites and lymphoid tissues (Lymph nodes, peyer’s patches)

Main function is to present antigens to T and B cells

Initiate immune response

Promote tolerance towards harmless microorganism or to self antigens

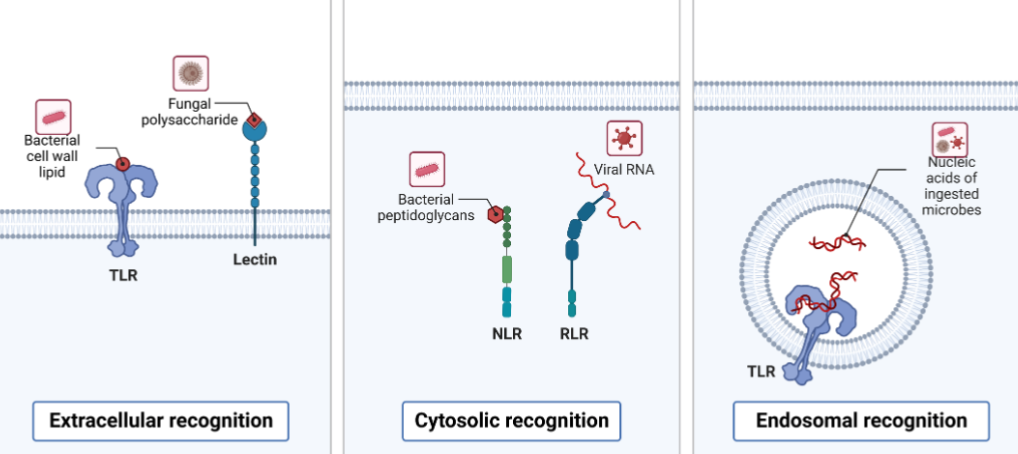

Sensing Mechanisms of Innate Immunity

Coordination of the innate immune response relies on the information provided by many types of receptors

Pattern recognition Receptors (PRRs)

Evolutionarily ancient pathogen system of recognition and signaling

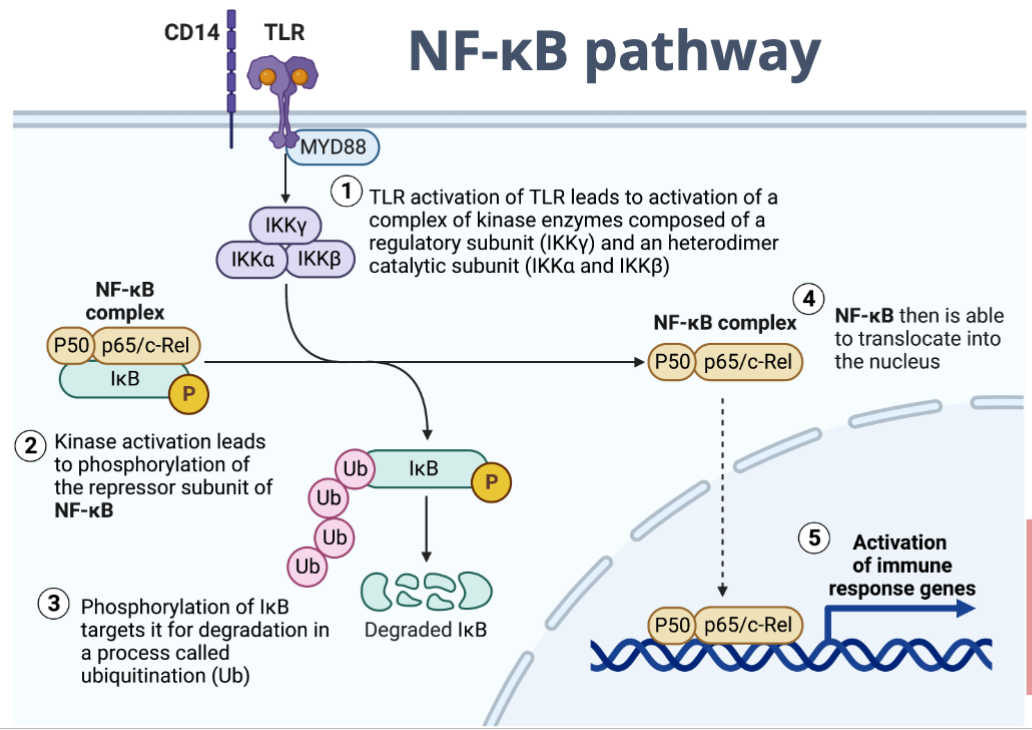

Toll Like Receptors

Limited specificity compared with the antigen receptors of the adaptive immune system

Recognize elements of most pathogenic microbes

Are expressed by many types of cells:

Macrophages

Dendritic cells

B cells

Stromal cells

Certain epithelial cells

Enabling the initiation of antimicrobial responses in many tissues

Toll-like receptor family (10 in humans and in cattle, 12 in mice)

Extracellular and intracellular

Bacterial, viral, year associated molecular patterns

NF-kB pathway

Cytokines and chemokines responsible for initiation of innate immune response

NOD Like Receptors

Nucleotide binding oligomerization dimer (NOD)- like receptors

Intracellular

NOD recognizes muramyl dipeptide from peptidoglycan

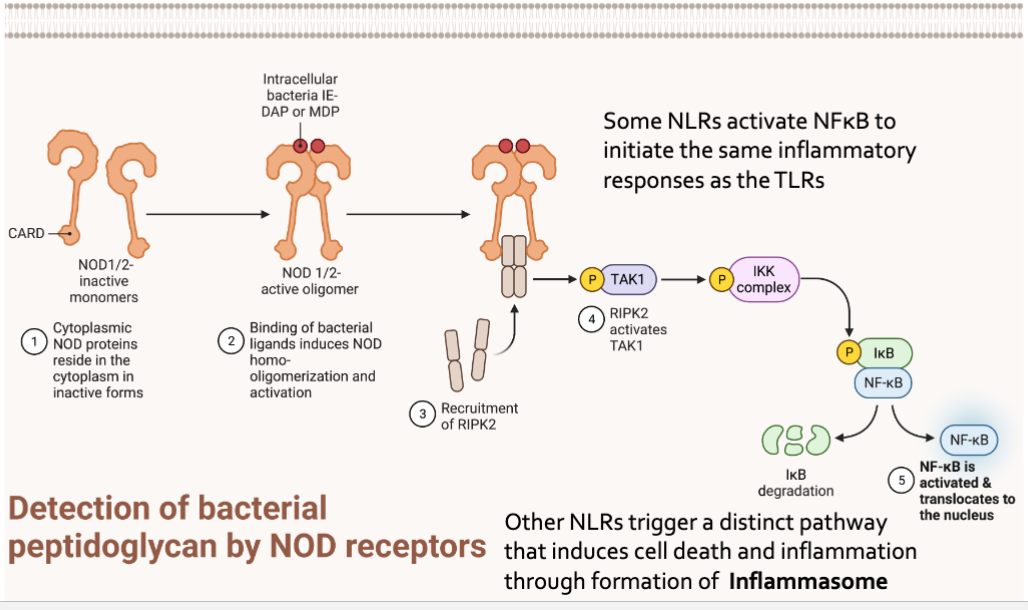

Detection of bacterial peptidoglycan by NOD receptors

Some NLR activate NFkB to initiate the same inflammatory response as the TLRs

Other NLRs trigger a distinct pathway that induces cell death and inflammation through formation of Inflamasome

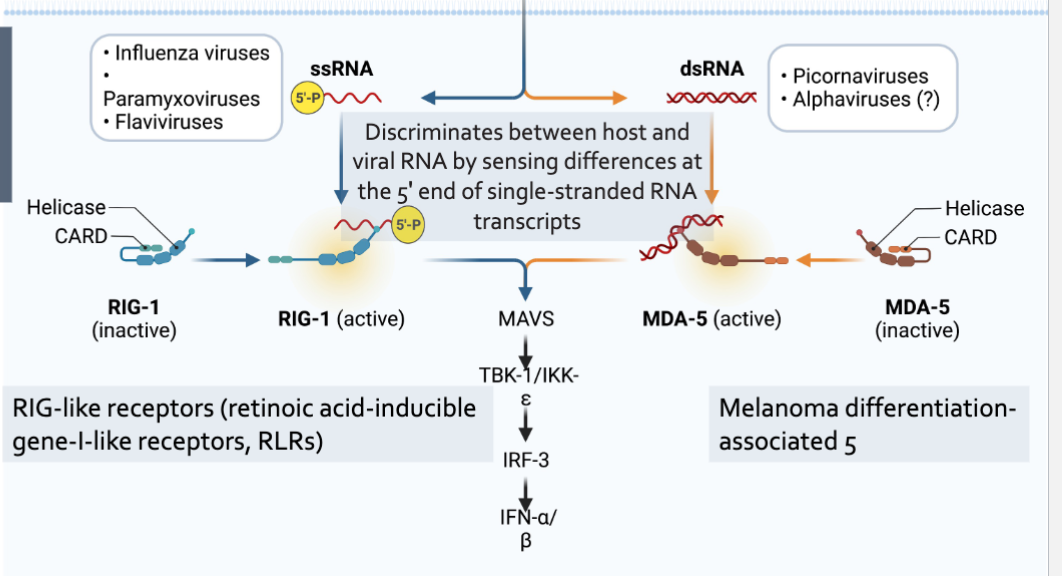

RIG-I and MDA-5

Intracellular pattern recognition receptors

Involved in viral recognition

Sentinels for intracellular viral RNA produced within the cell in contract with TLRs

Provide frontline defense against viral infections in most tissues

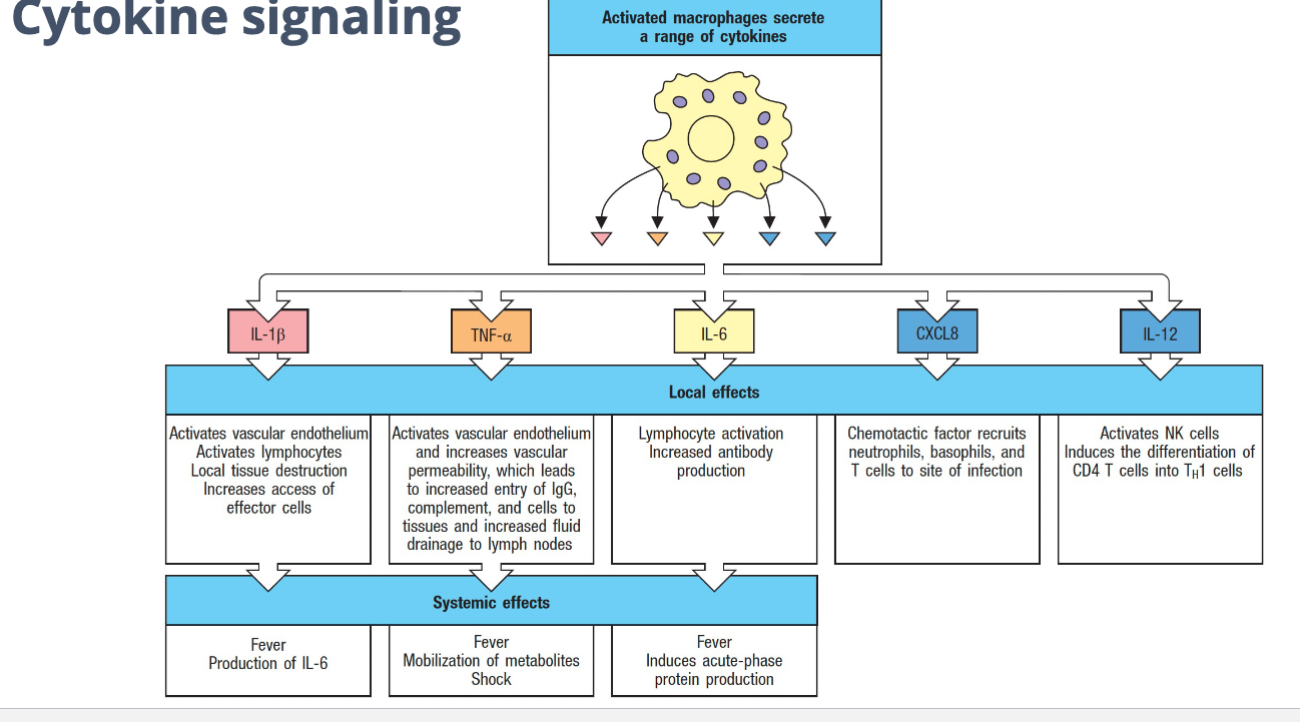

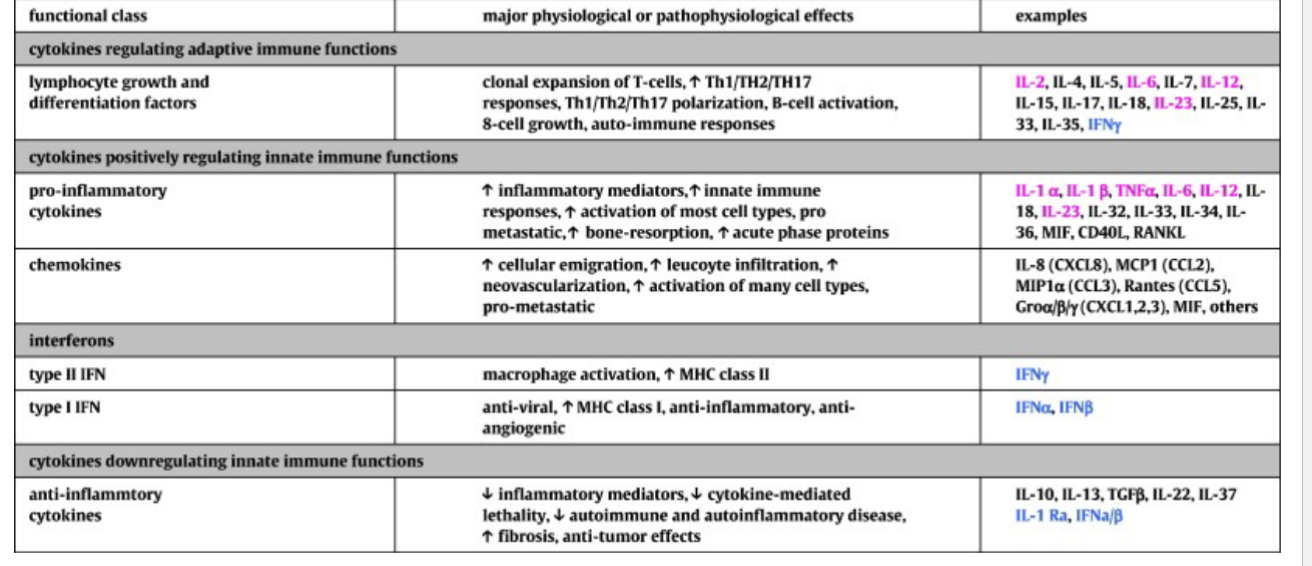

Cytokine Signaling

Activated macrophages secrete a range of cytokines

Local effects

Systemic effect

Cytokines signaling molecules of the immune system

Mammalian Inflammatory response in response to bacterial infiltration through the physical barrier

Inflammatory response

Sensed by the integrated mast cells; neutrophils. Macrophages and effectors cells

Production of cytokines and chemokines

Interleukin-1beta

Interleukin-6

Interkelin-12

TNF-alpha

Vasodilation

Immune cell recruitment

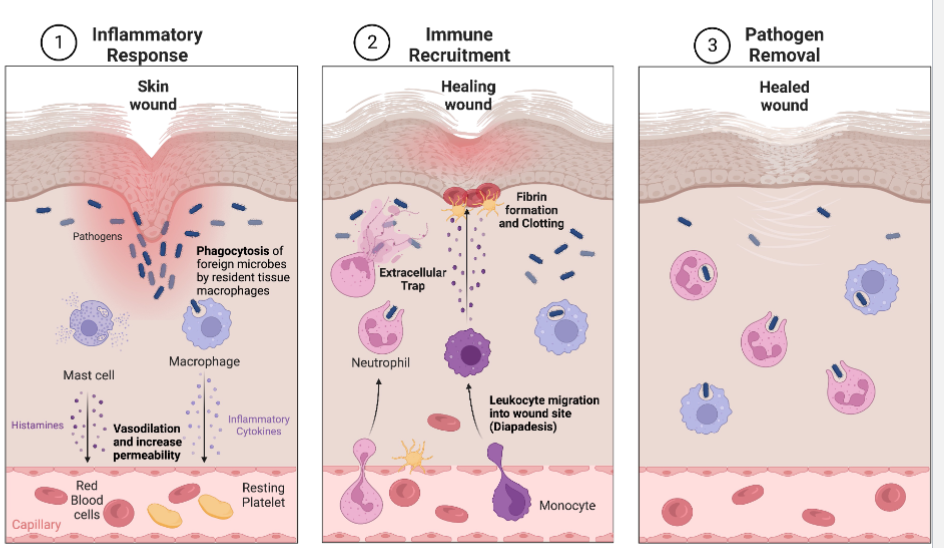

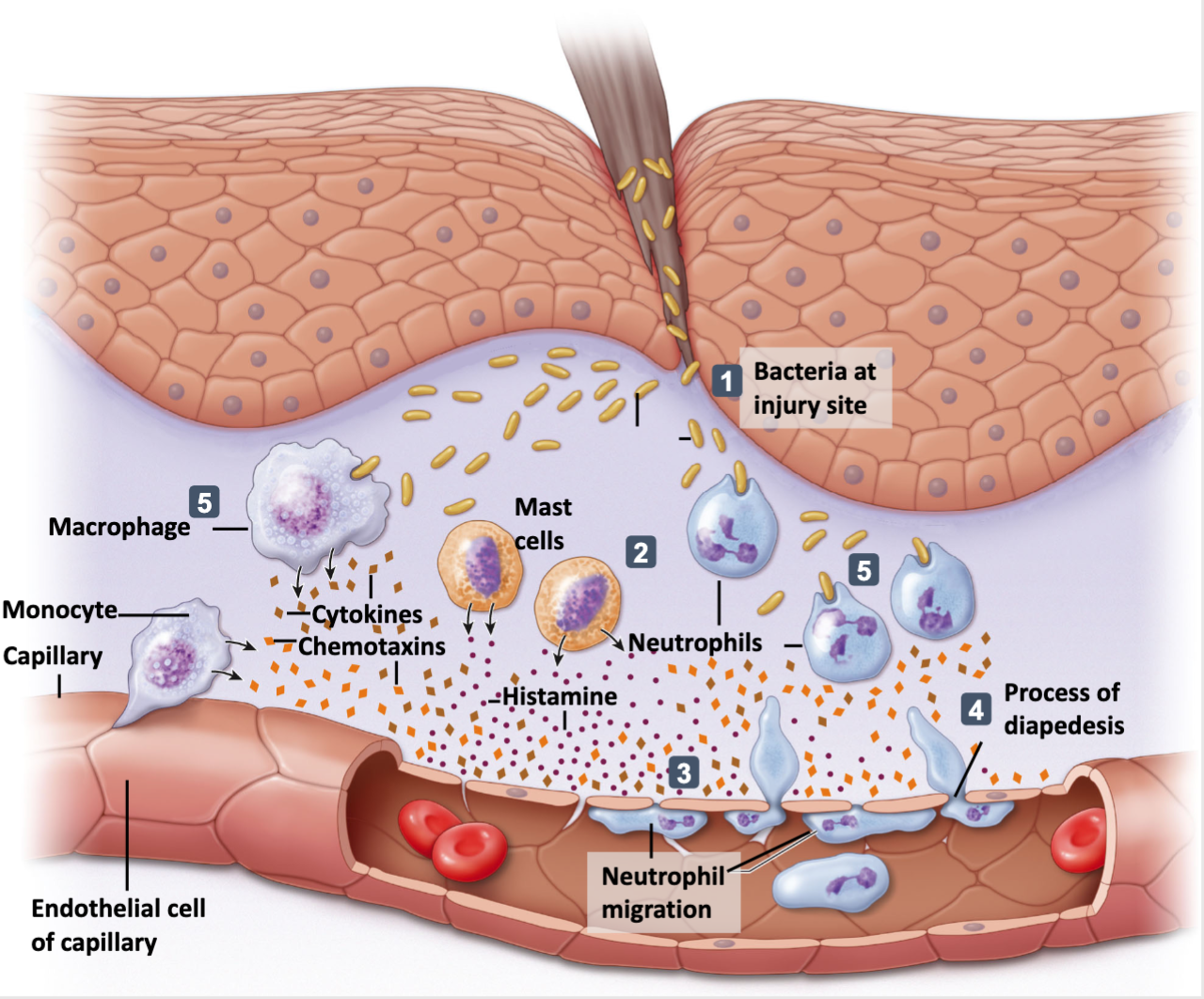

Wound Healing

Pathogen infiltration through wound

Mast cells secrete factors that mediate vasodilation and vascular constriction. Delivery of blood, plasma, platelets and cells to injured area increases

Platelets from blood release blood-clotting proteins at wound site

Neutrophils secrete factors that kills and degrade pathogens

Neutrophil and macrophages remove pathogens by phagocytosis

Macrophages secrete hormones called cytokines that attract immune system cells ot the site and activate cells involved in tissue repair

Inflammatory response continues until the foreign material eliminated and the wound is repaired

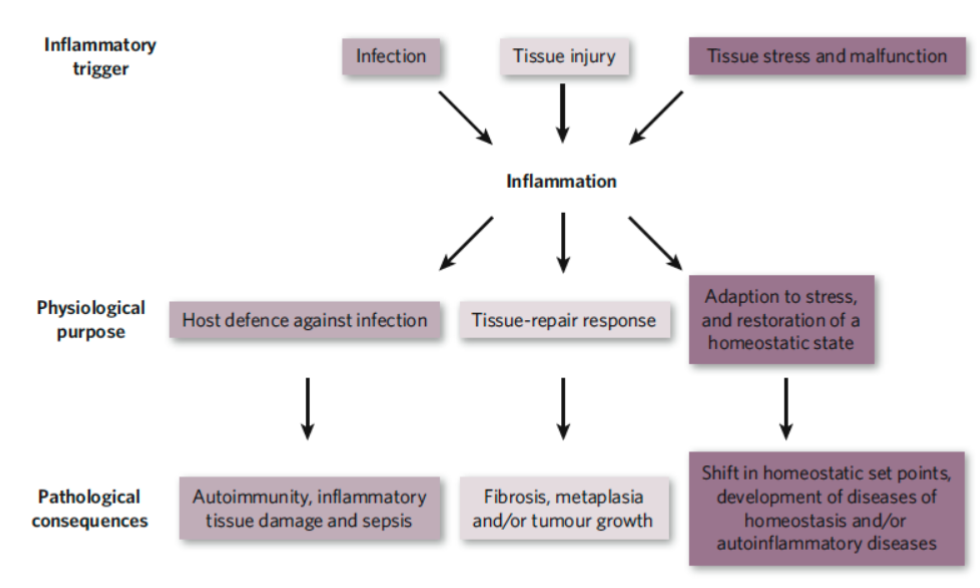

Map

Inflammatory trigger → inflammation → physiological purpose → pathological consequences

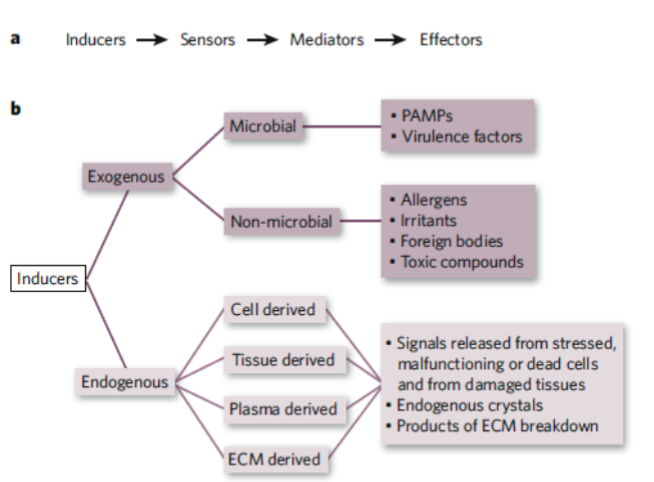

Inducers of Inflammations

Exogenous Inducers

Pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPS)

Virulence factors from microbial inducers

Commensal bacteria which can also induce inflammation (through TLRs)

Non-microbial origin: allergens, irritants, foreign bodies, toxic compounds

Foreign bodies

Endogenous Inducers

Sequestration of cells or molecules kept in intact cells and tissues

Necrotic cell death

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Damage to vascular endothelium

Chronic inflammation

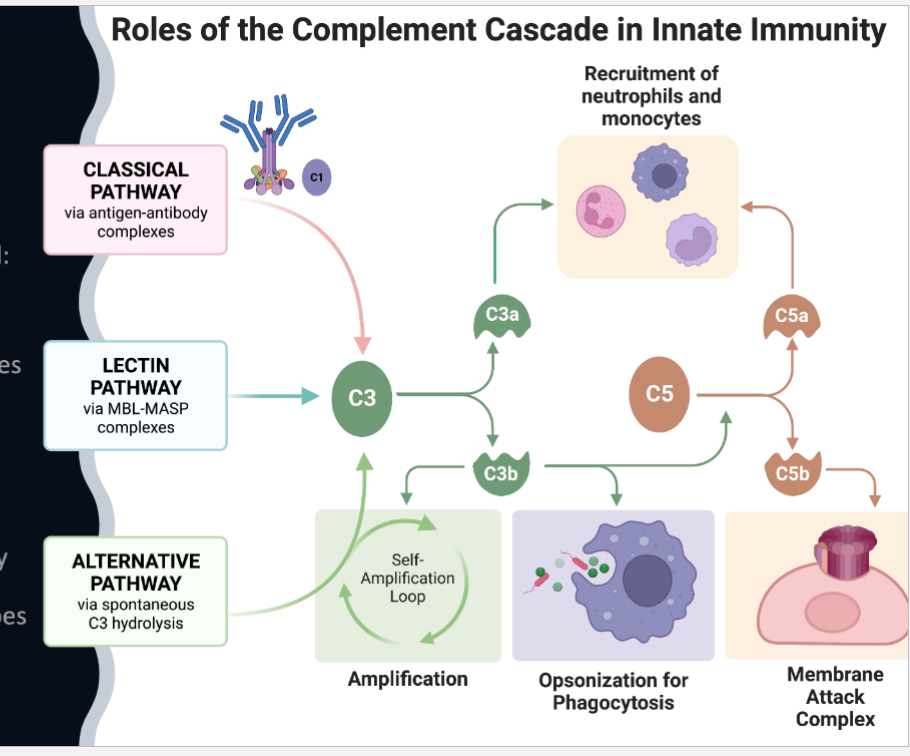

Complement System

Nine plasma proteins (C1 to C9) that are produced by the liver and circulate in the blood in inactive form

Sequential activation leads to assembly of large donut-shaped membrane attack complex (MAC) with the assembly of the C5-C9

MAC inserts in microorganism to form pores

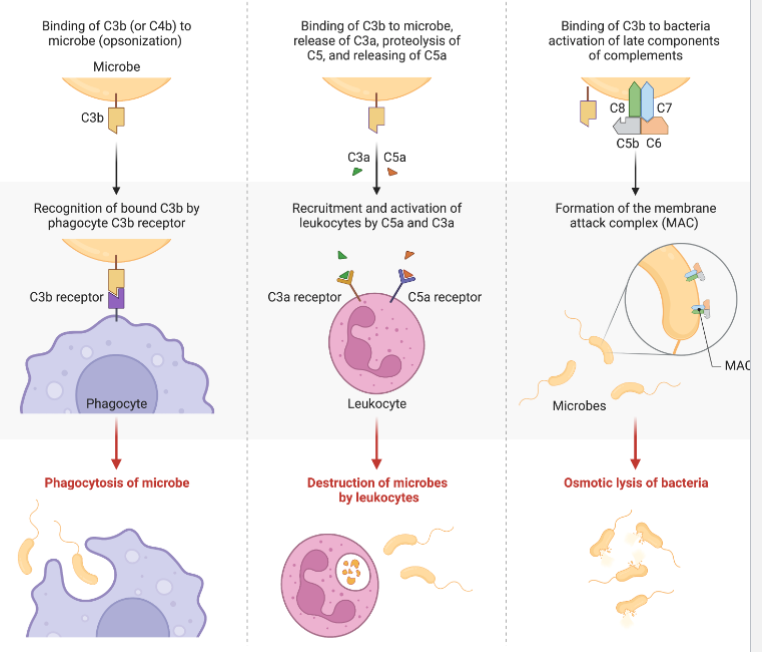

3 outcomes of complement activation

Complement System

Antimicrobial response continued: complement pathway

Cascade sequences that amplify

Classical:

binding to antibodies (adaptive)

Alternative:

directly binds to foreign invader (innate) - polysaccharides from yeast, gram negative bacteria

Lectin Pathway:

stimulated by mannose containing proteins and carbohydrates on microbes (viruses and yeast)

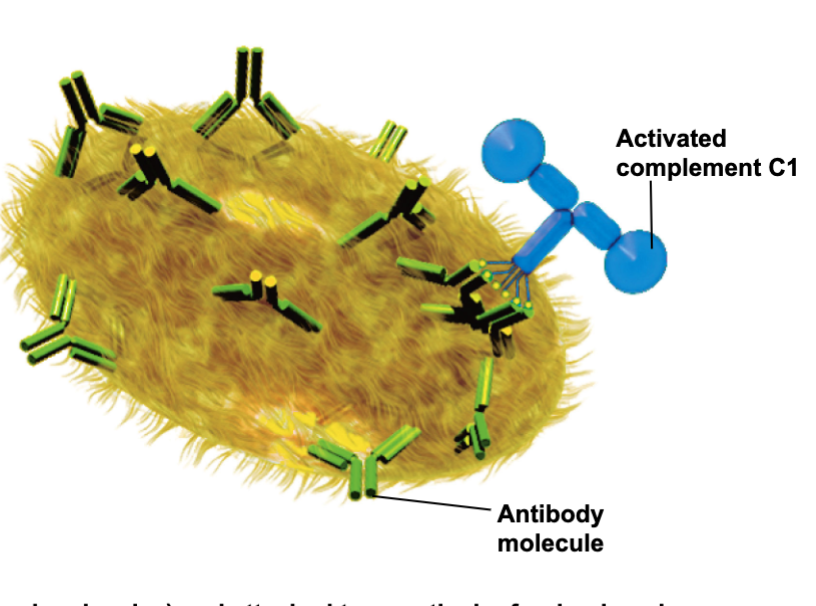

Complement System: Classical pathway

Binding to antibodies(Y-shaped molecules) and attached to a particular foreign invader

Initiates complement activation cascade

Activated complement C1

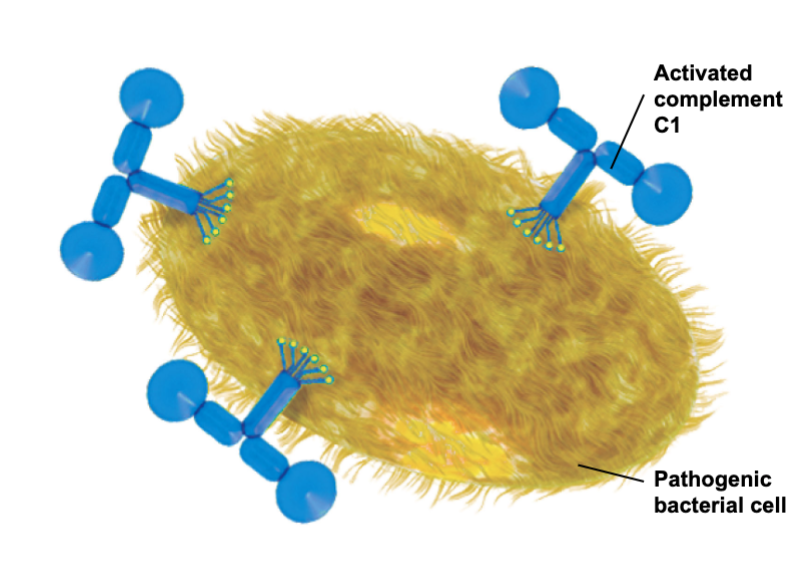

Complement System: Alternative Pathway

Binding directly to a foreign invader non specifically activates the complement cascade

Activates complement C1

Pathogenic bacterial cell

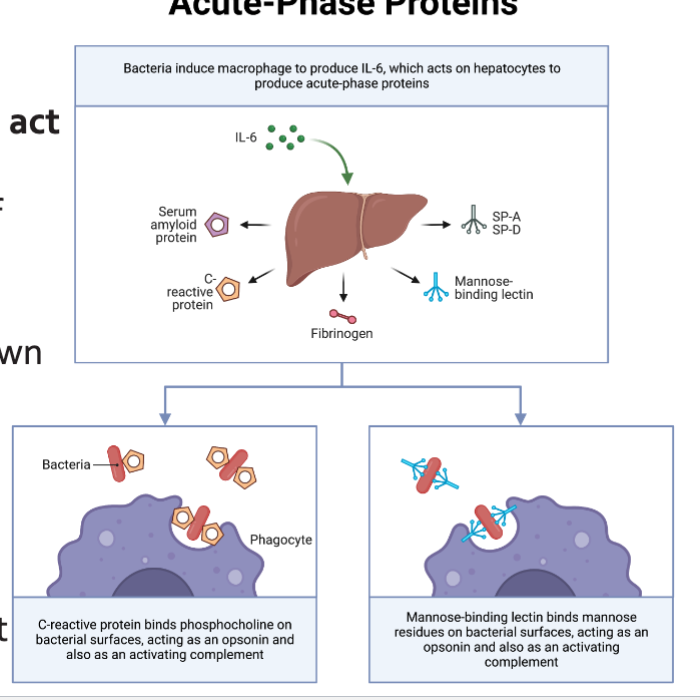

The Acute phase response

Cytokines (TND-a, IL1B, and IL-6) act on hepatocyte toL

Promotes a change in the profile of proteins that they synthesize

Blood levels of some proteins go down (Albumin), whereas levels of others increase markedly (SAA)

C-reactive protein: opsonization and complement activation

Serum Amyloid A: chemoattractant and inflammasome activation

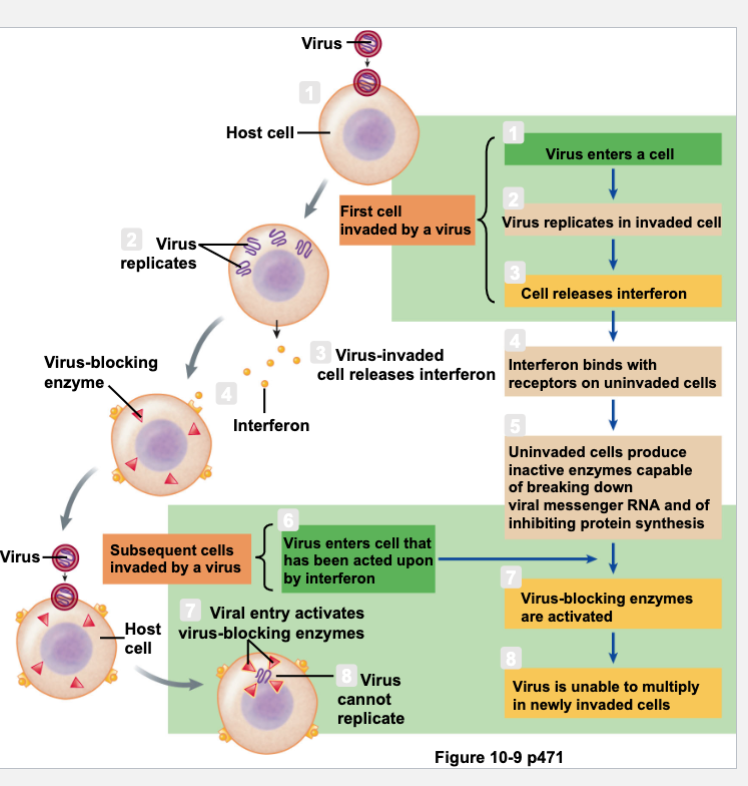

Role of Interferon in Viral Defense Mechanisms

Called interferon because it interferes with viral replication

Block spread of viral replication on neighboring cells

Signal neighboring cells to put up barriers

Signal infected cells to die

Recruitment of white blood cells to stimulate long lasting immunity

Released from virus-infected cells

Transiently interferes with viral replication

Enhance actions of NK cells

Slows cell division and suppresses tumor growth

SARS-COV-2 interferes with interferon signaling

SARS-CoV-2 inhibits multiple arms of the type I IFN response: Reduce IFN-b production during infection. Inhibits recognition of the foreign viral RNA by RIG-I Inhibits phosphorylation of repressor subunit of NF-kB Reducing import into the nucleus and reducing transcription of type I IFN

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 on respiration

Moderate damage: accumulating fluid, reduced gas exchange

Severe damage: build up of protein-rich fluid, vert limited on gas exchange

Cytokine Storm

Coronavirus infects lung cells

Immune cells, including macrophages, identify the virus and produce cytokines

Cytokines attract more immune cells, such as white blood cells, which in turn produce more cytokines, creating a cycle of inflammation that damages the lung cells

Damage can occur through formation of fibrin

Weakened blood vessels allow fluid to seep in and fill the lung cavities leading to respiratory failure

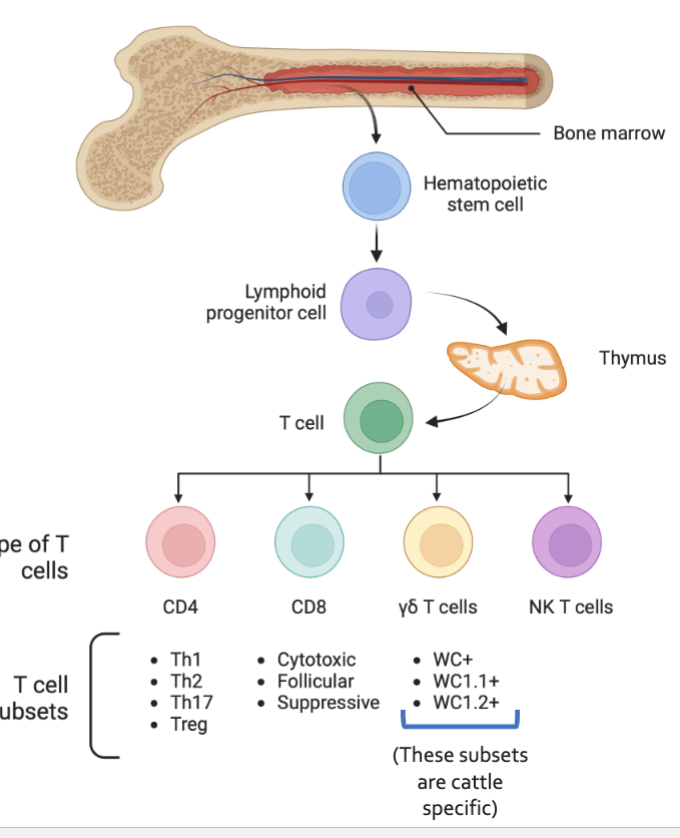

Adaptive Immune System-T Cell Development and Function: 03.19.24

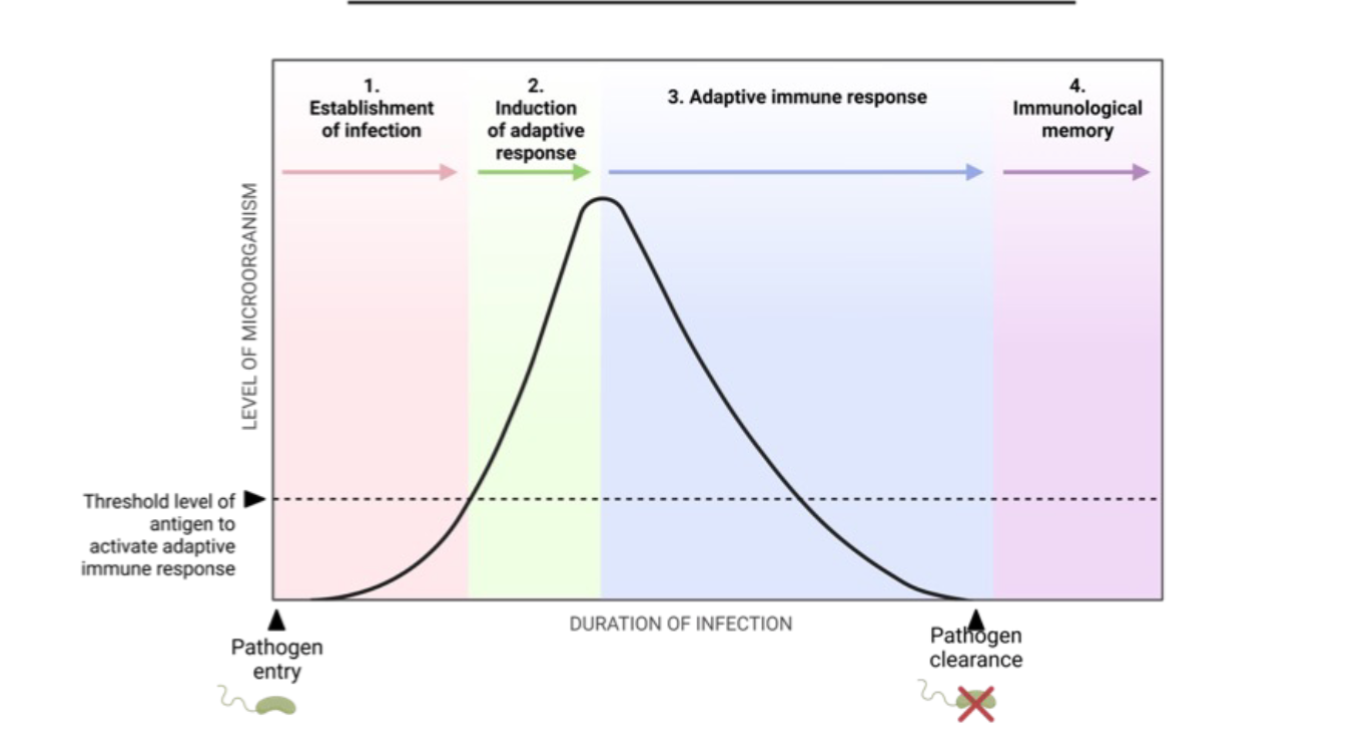

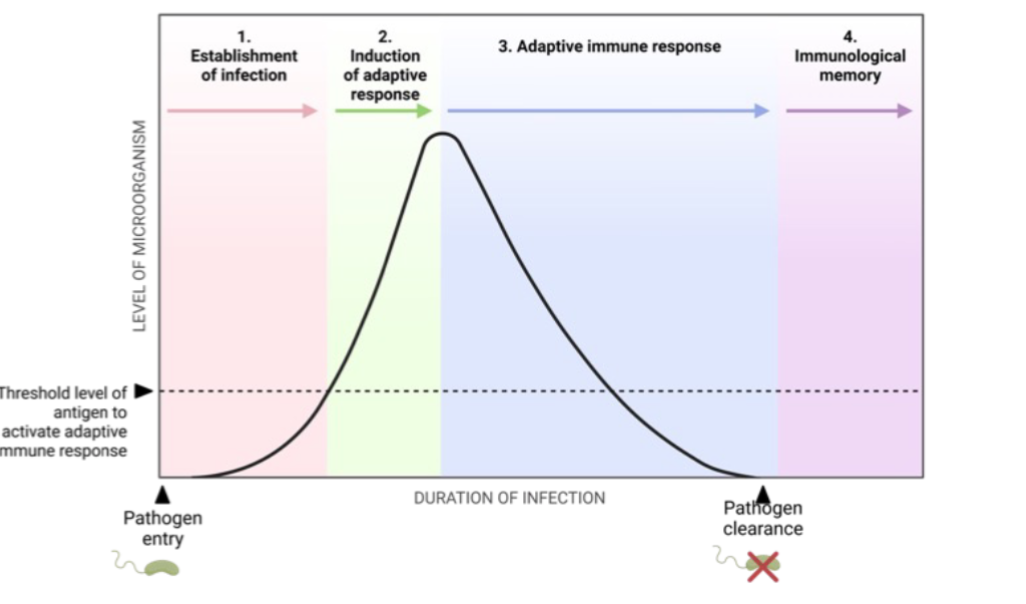

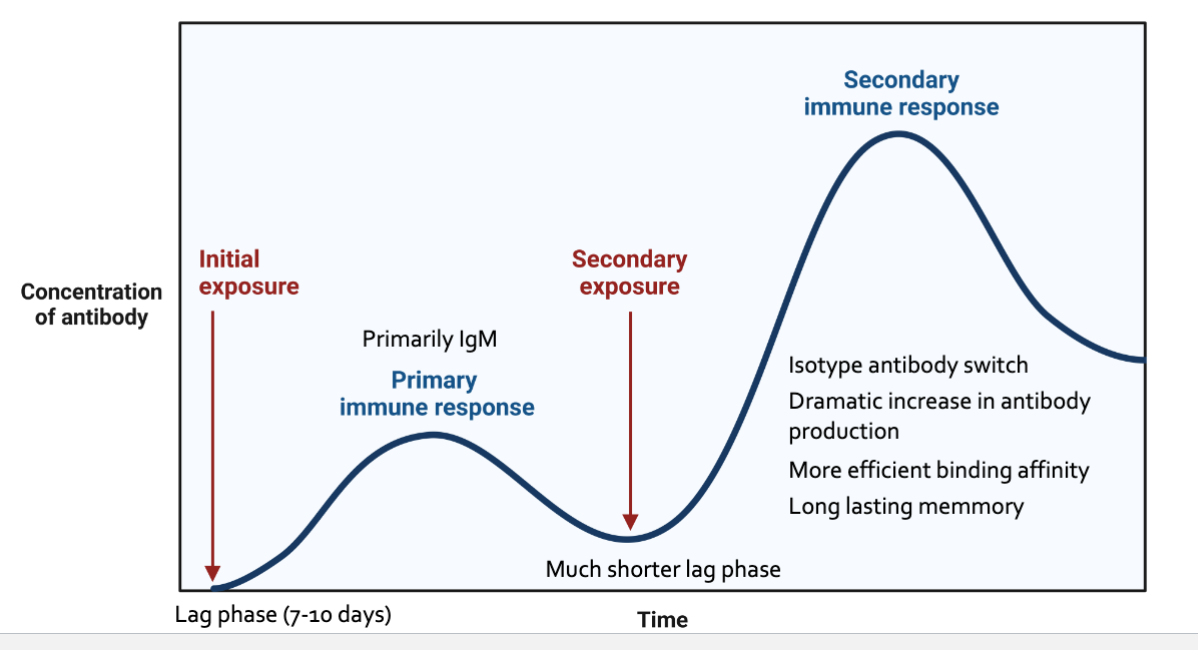

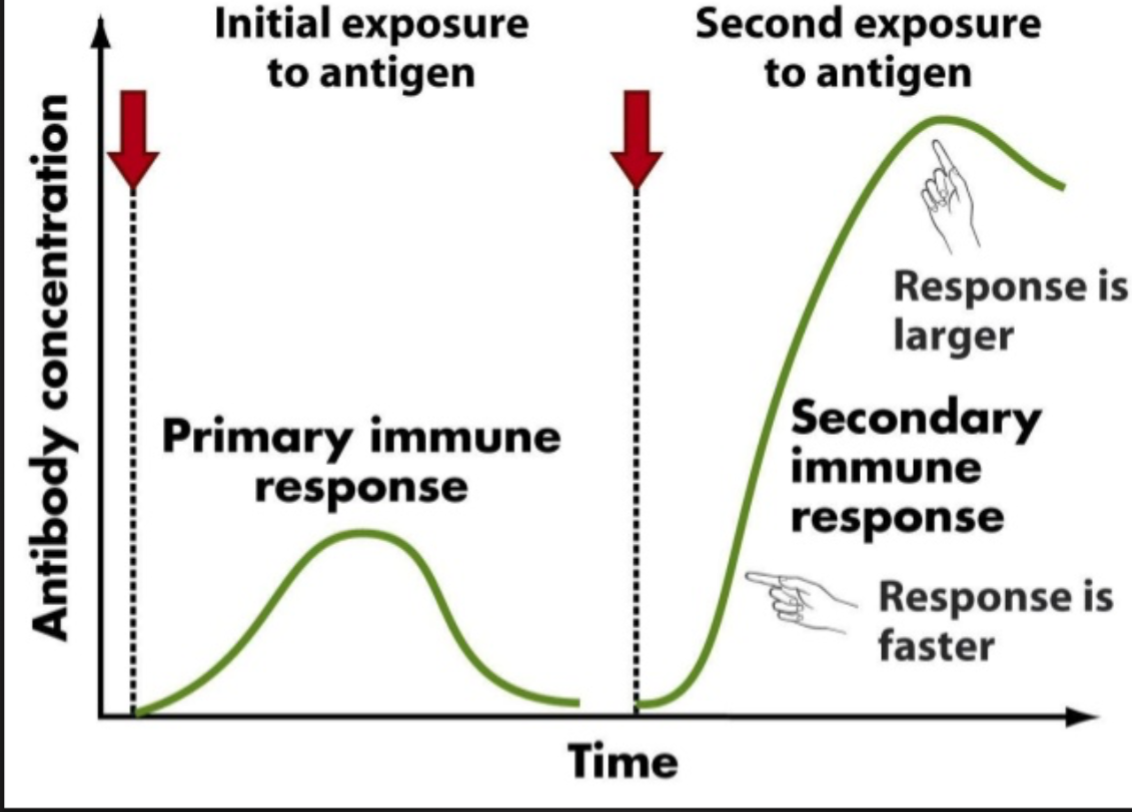

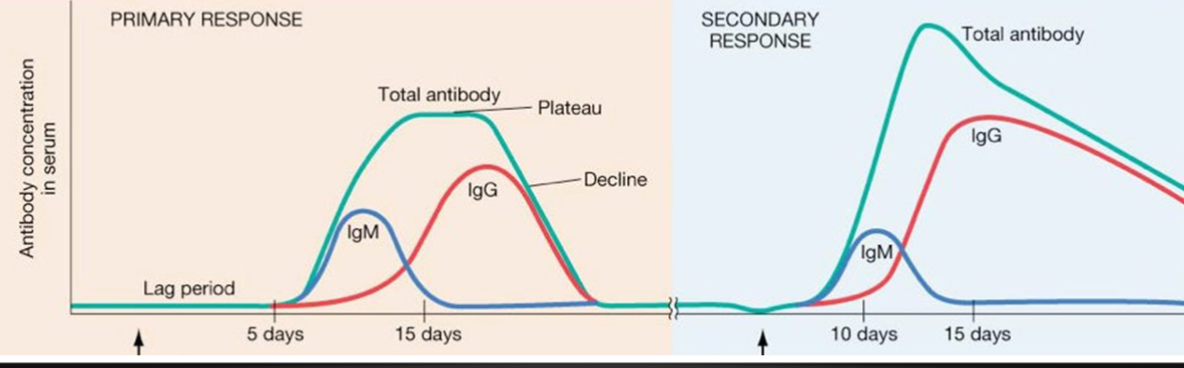

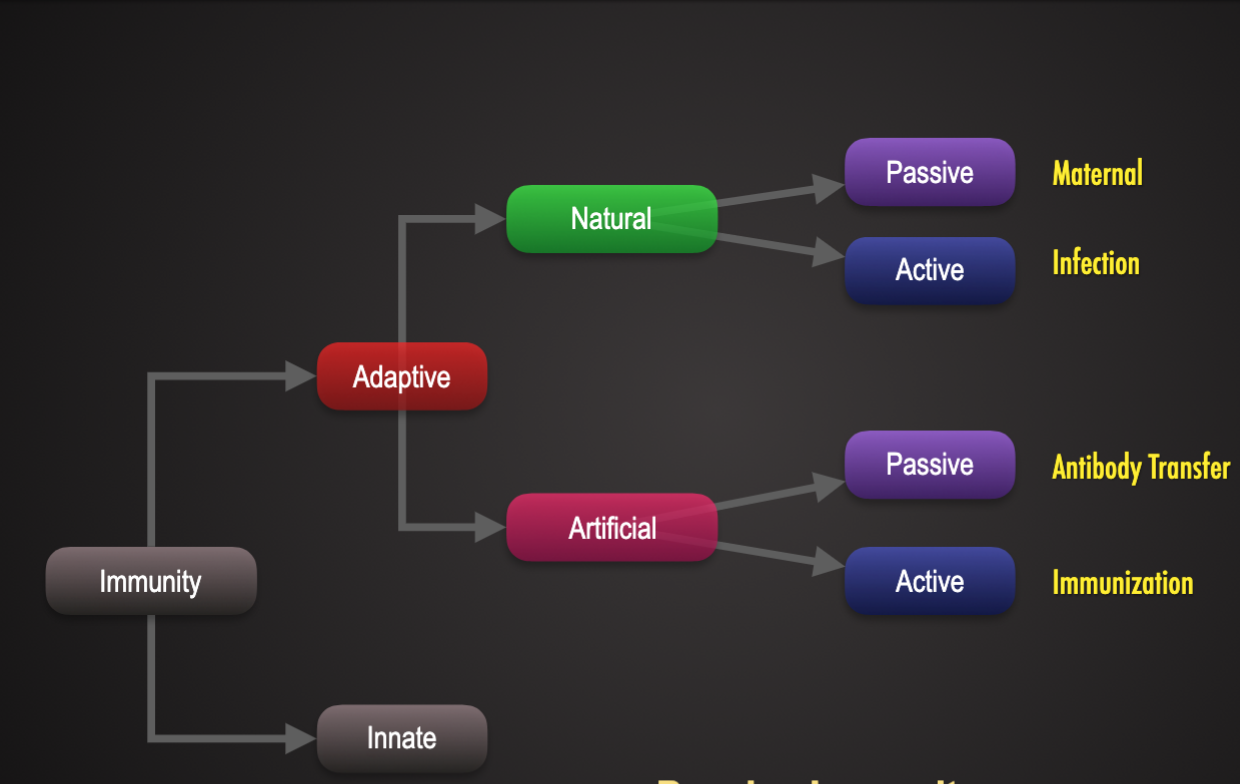

Stages of Adaptive Immune Response

Components of the immune system: immune cells

Innate Immune System

Both have hematopoietic cell in bone marrow

Adaptive Immune System

Both have hematopoietic cell in bone marrow

Components of the immune system: Immune Cells

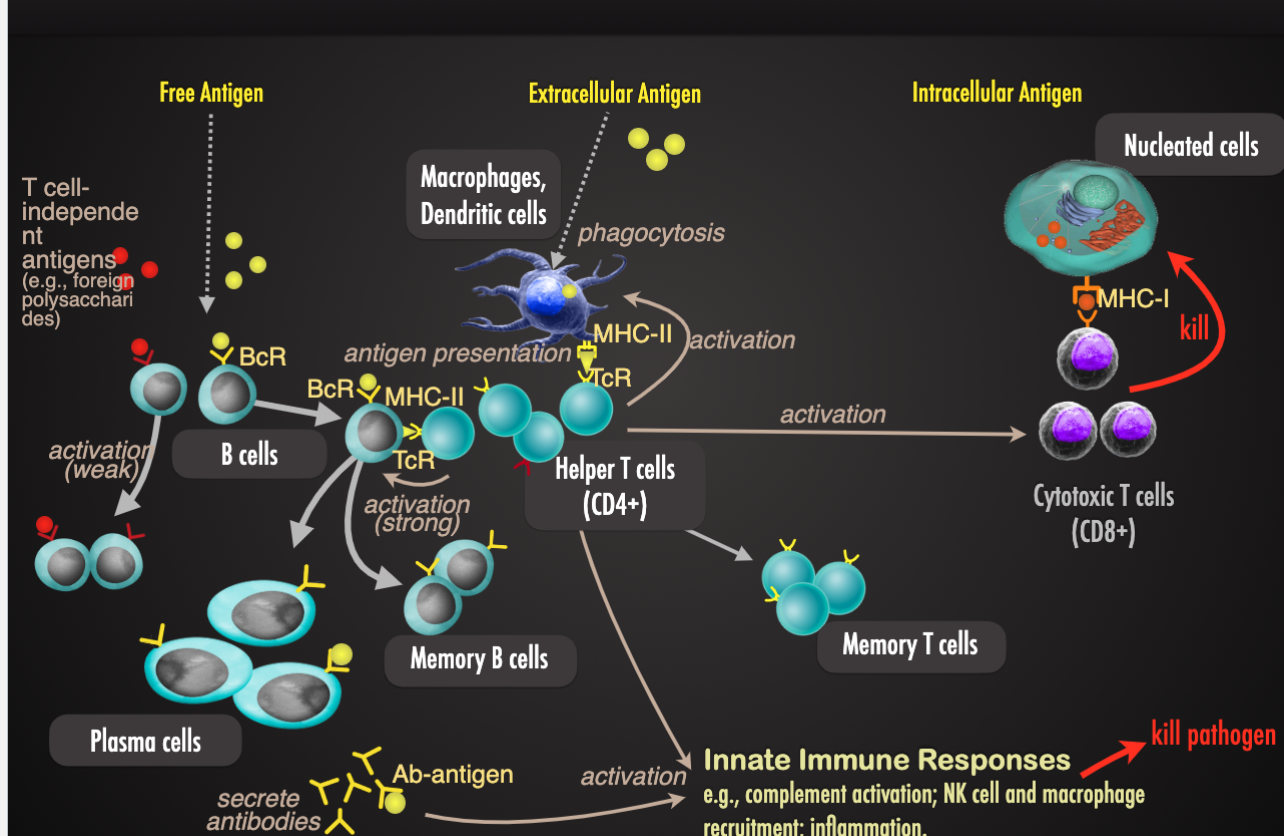

T cells recognize specific antigen fragments presented by other cells

Orchestrate immune responses to eliminate pathogens, infected cells, and abnormal cells

The vast diversity of function between different T cell subsets ensures that responses are tailored to the specific need

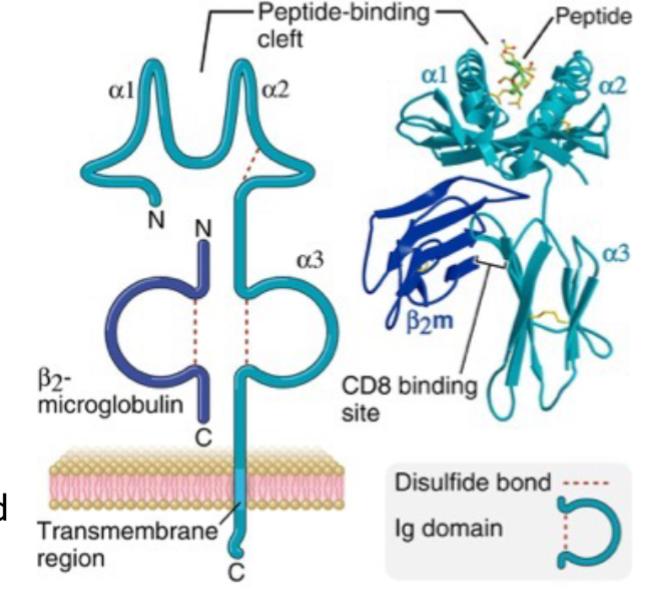

T Cell Development in Thymus

Selection process

Positive selection

Negative selection

Enter circulation as

CD4+: T Helper Cell

CD8+: Cytotoxic T cell

Treg: T regulatory cell

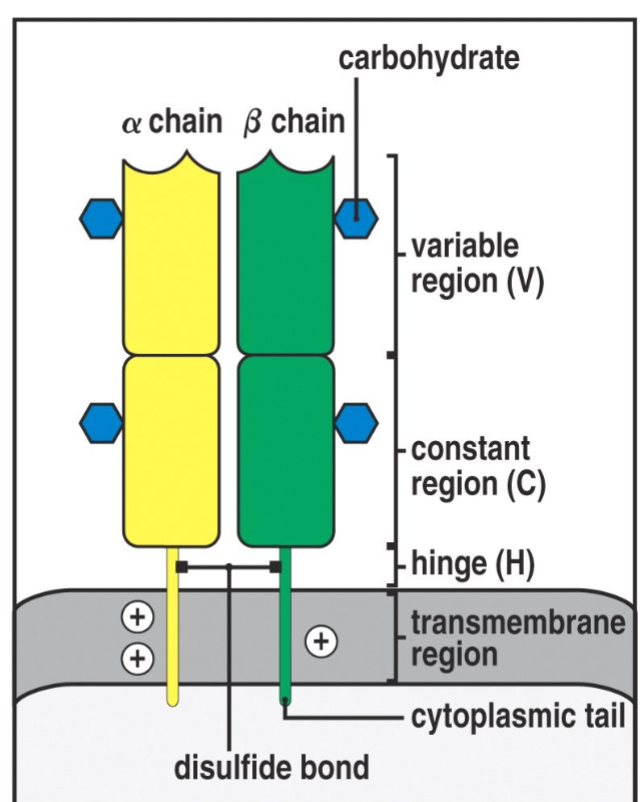

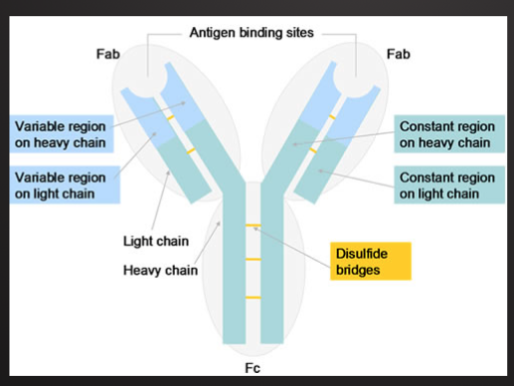

T Cell Receptor

Recognize specific antigen via the T CELL RECEPTOR (TCR)

TCR is a multi-subunit surface protein

Constant region

Variable region

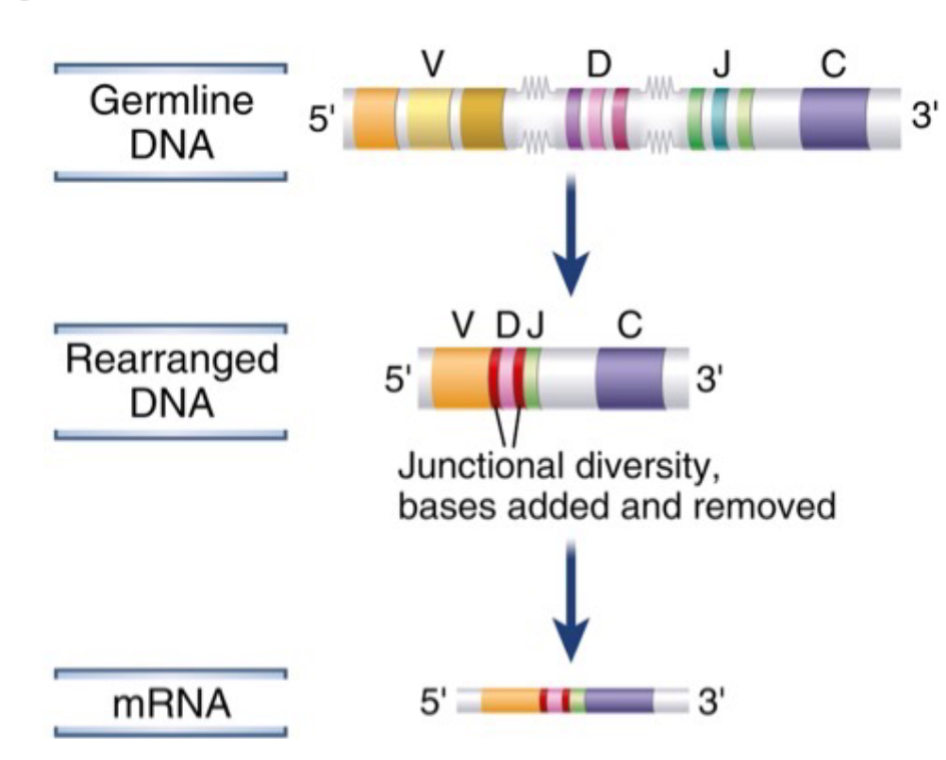

How million of different antigen receptors can be generated from a limited amount of coding DNA in the genome

Gene Recombination

Diversity of TCR is accomplish by unique random genetic rearrangement of germline gene segments

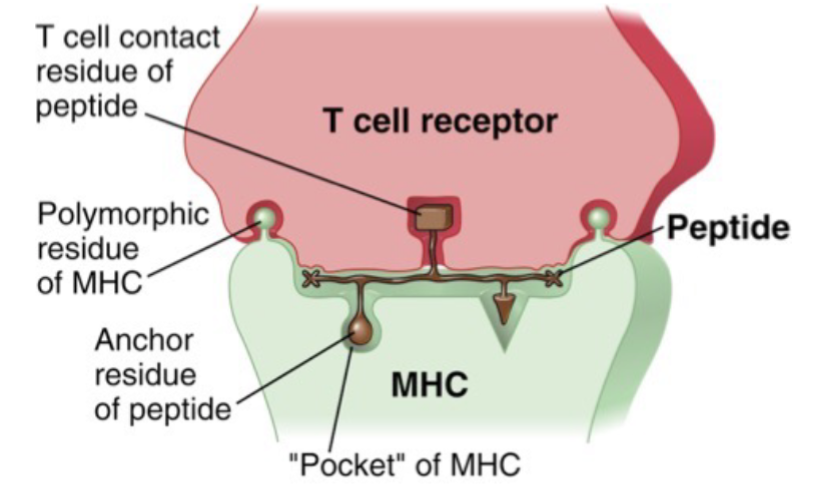

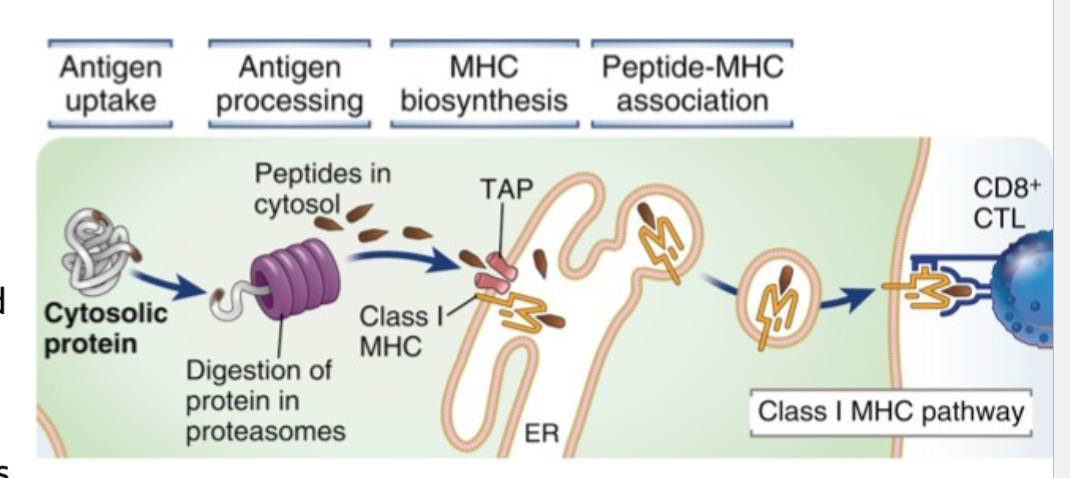

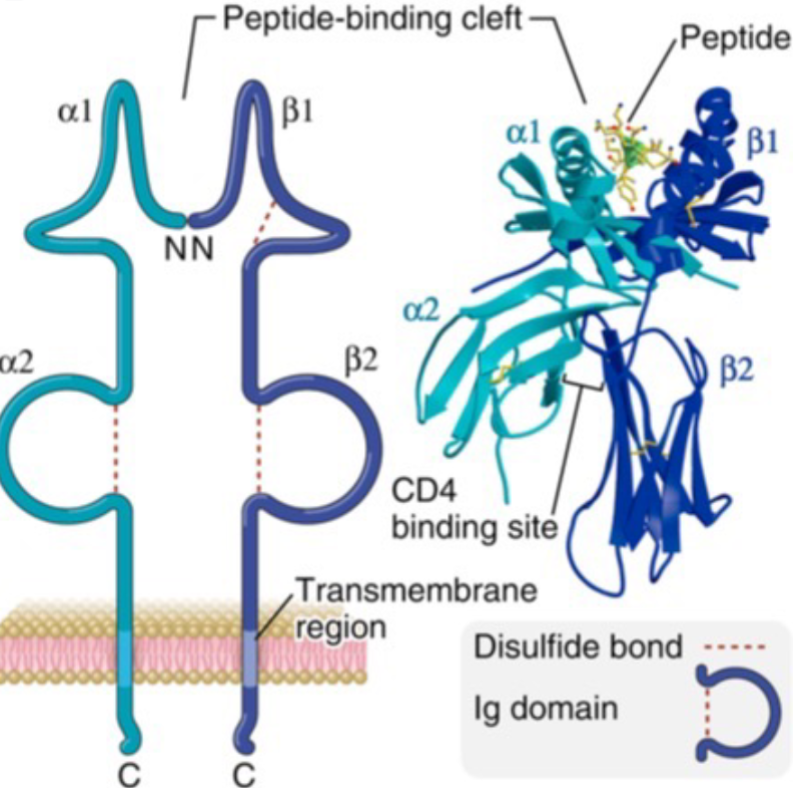

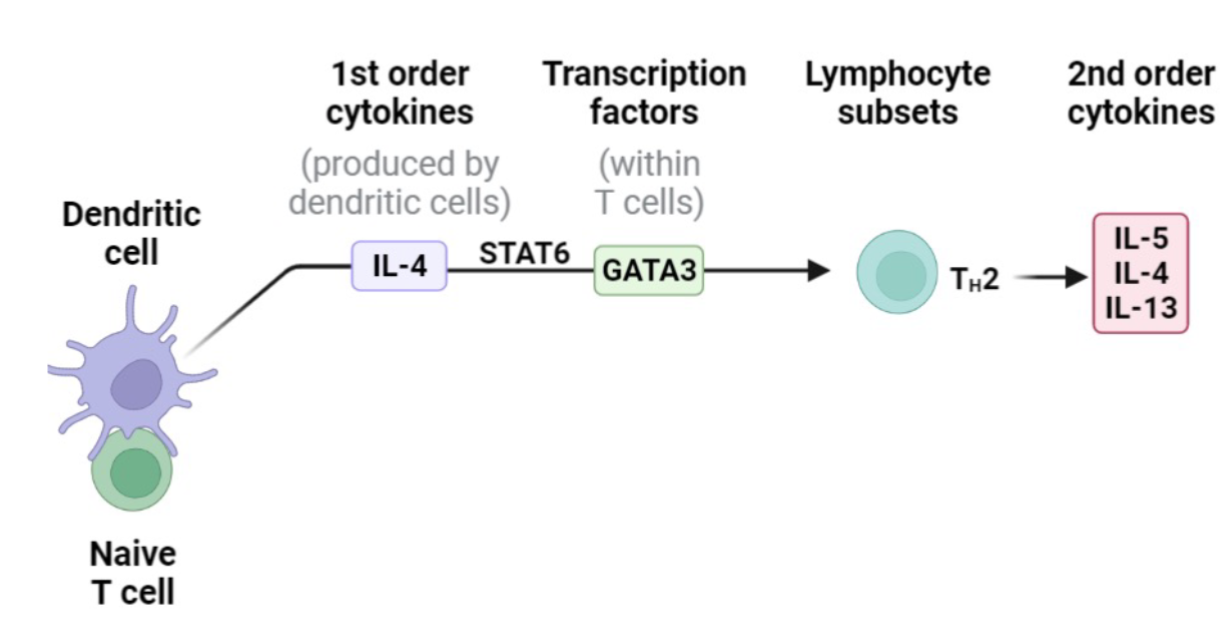

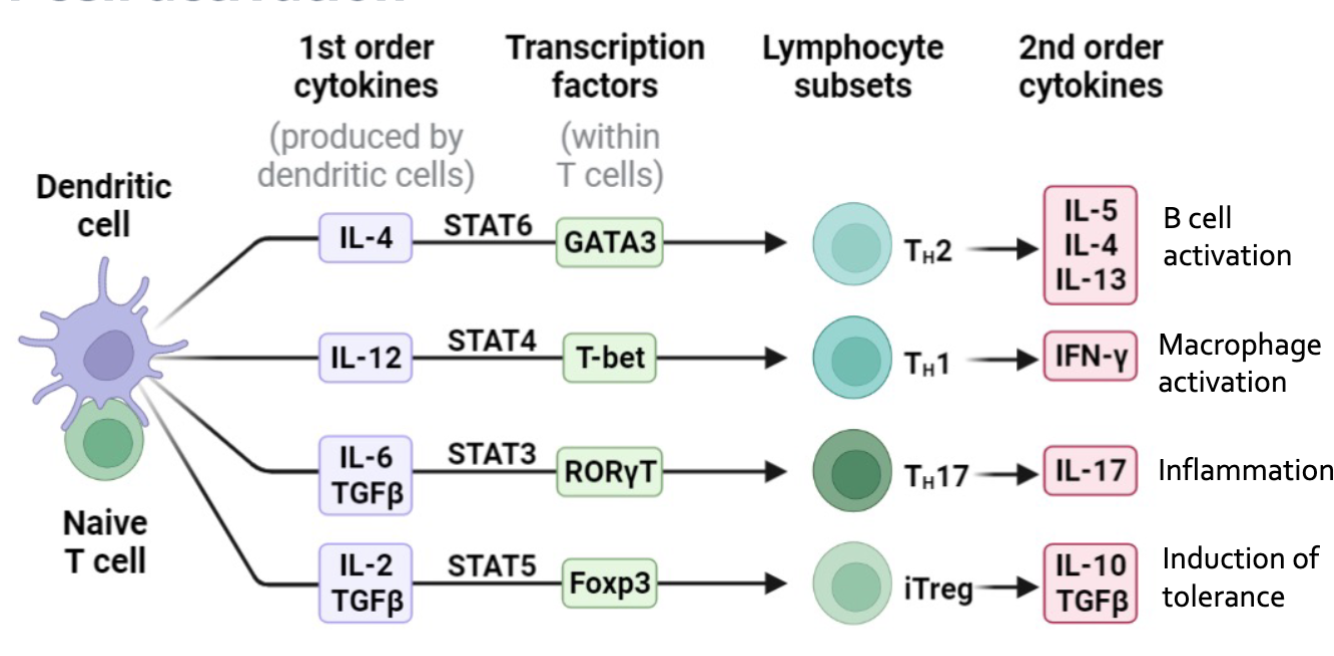

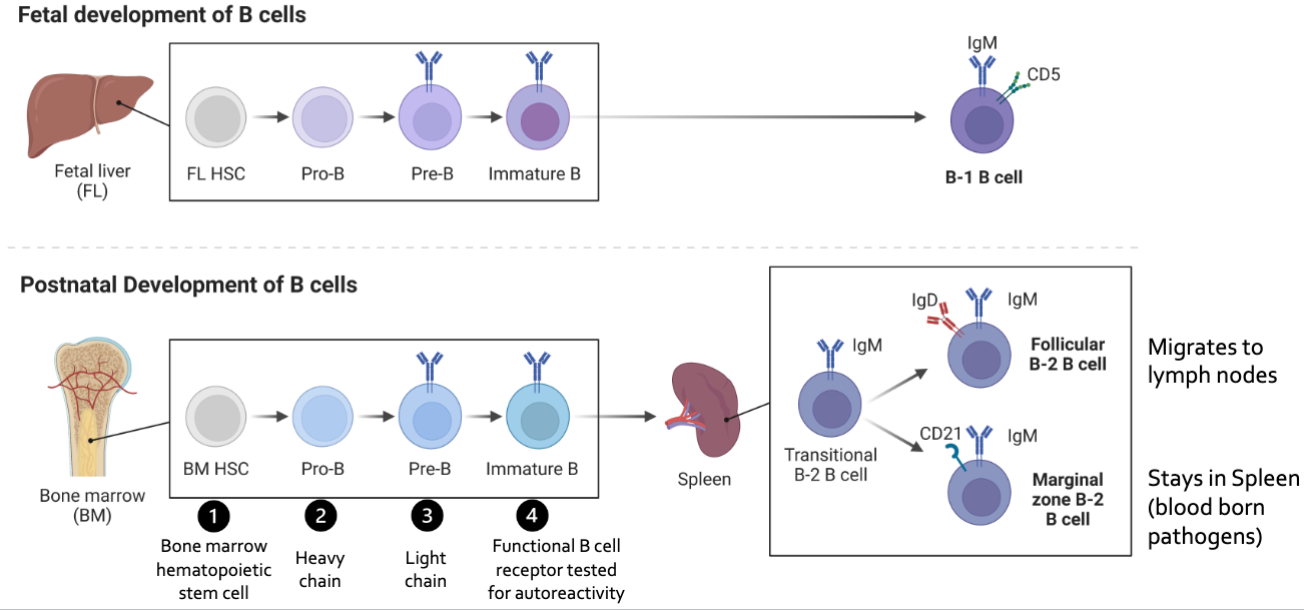

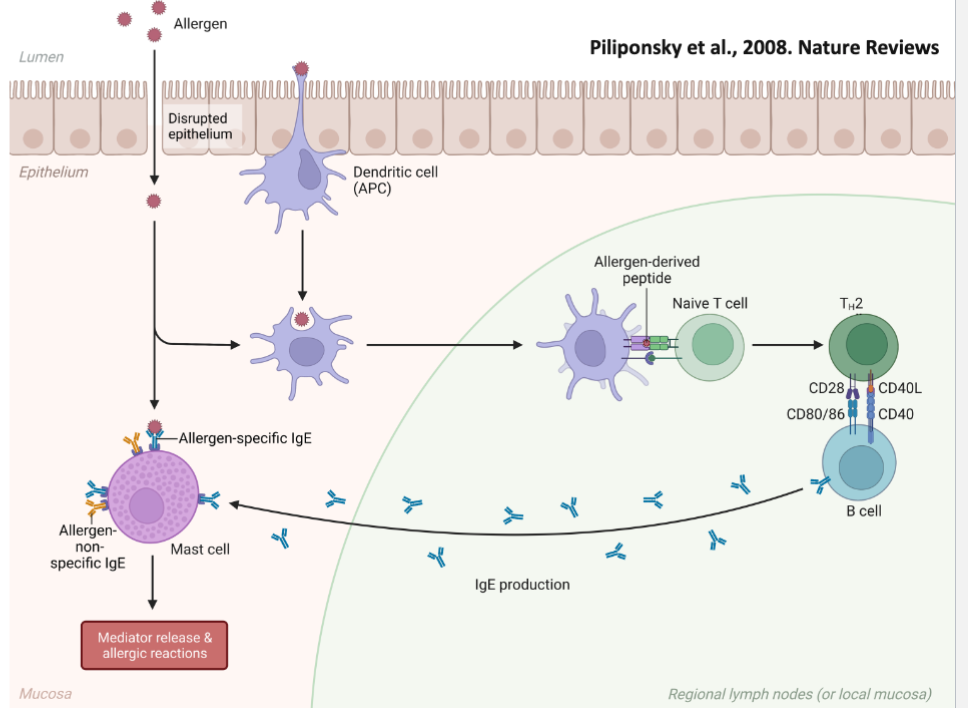

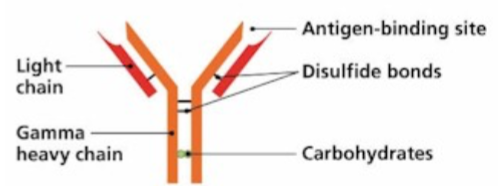

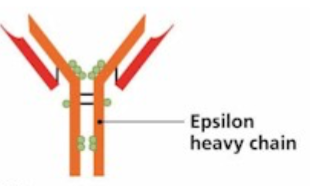

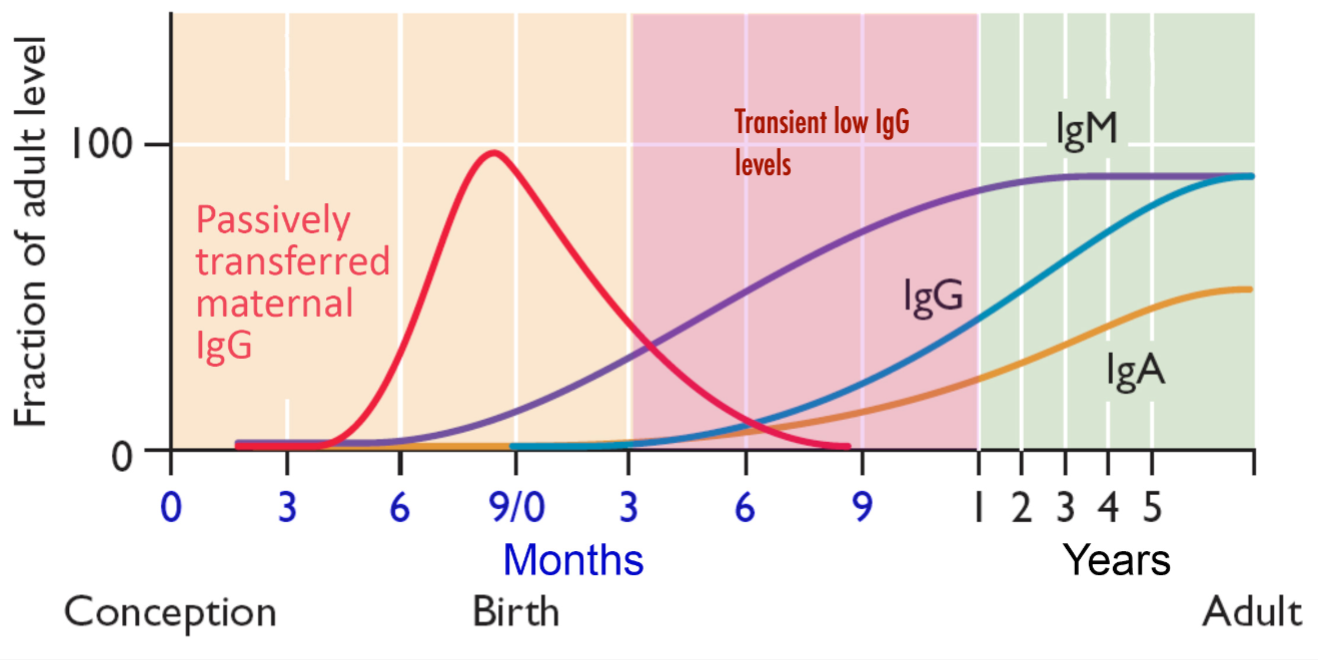

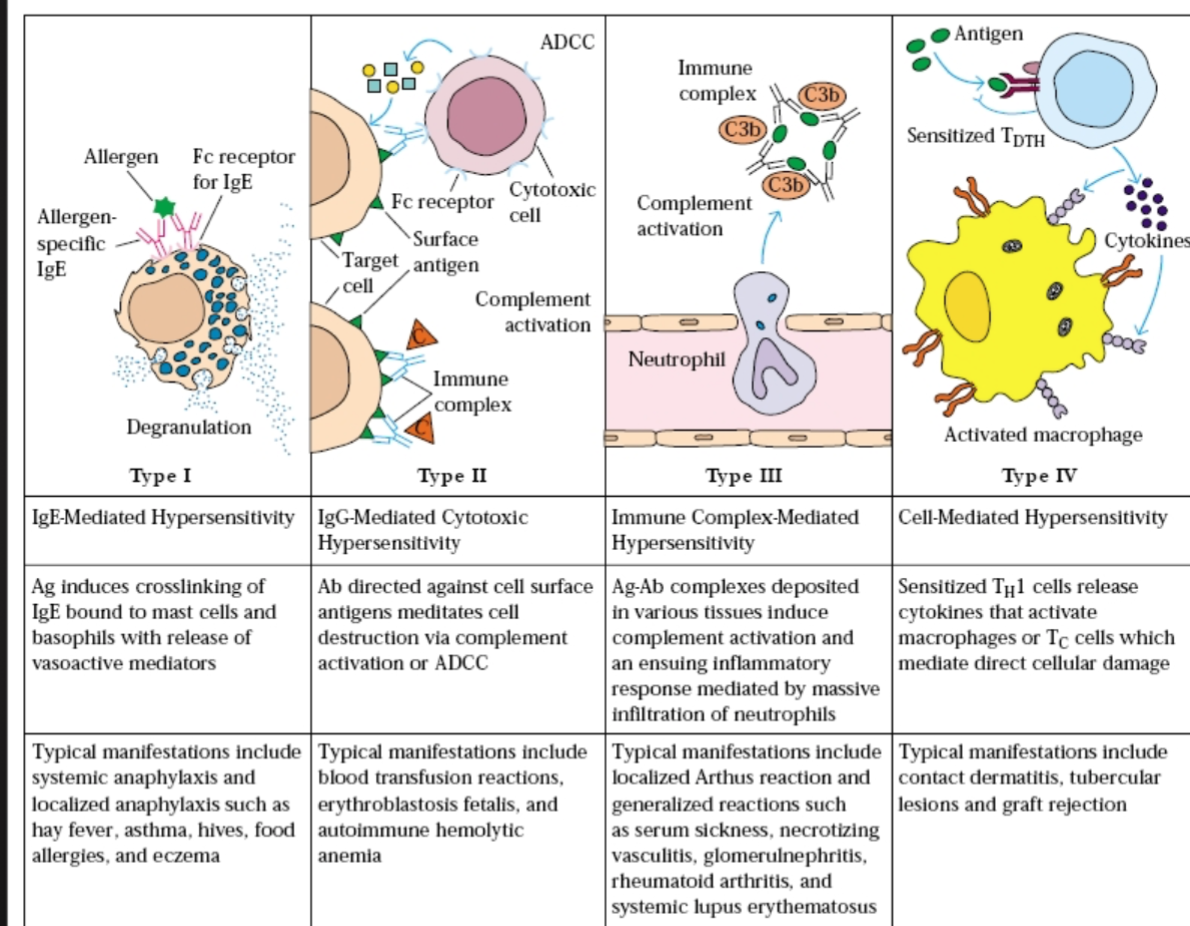

Functional receptors are created during T cell development in the thymus by randomly choosing V, D and J gene segment