AP Psychology Ultimate Guide

Unit 1: Scientific Foundations of Psychology

Roots of Psychology

Roots of psychology can be traced to philosophy and physiology/biology over 2,000 years ago in ancient Greece.

As a result of examining organisms, physician/philosopher/physiologist Hippocrates thought the mind or soul resided in the brain but was not composed of physical substance (mind-body dualism).

Philosopher Plato (circa 350 BC), who also believed in dualism, used self-examination of inner ideas and experiences to conclude that who we are and what we know are innate (inborn).

Plato’s student, Aristotle, believed that the mind/soul results from our anatomy and physiological processes (monism), that reality is best studied by observation, and that who we are and what we know are acquired from experience.

Descartes defended mind-body dualism (Cogito ergo sum—“I think, therefore I am”) and that what we know is innate.

Empirical philosopher Locke believed that mind and body interact symmetrically (monism), knowledge comes from observation, and what we know comes from experience since we are born without knowledge, “a blank slate” (tabula rasa).

Nature-nurture controversy: which our behavior is inborn or learned through experience.

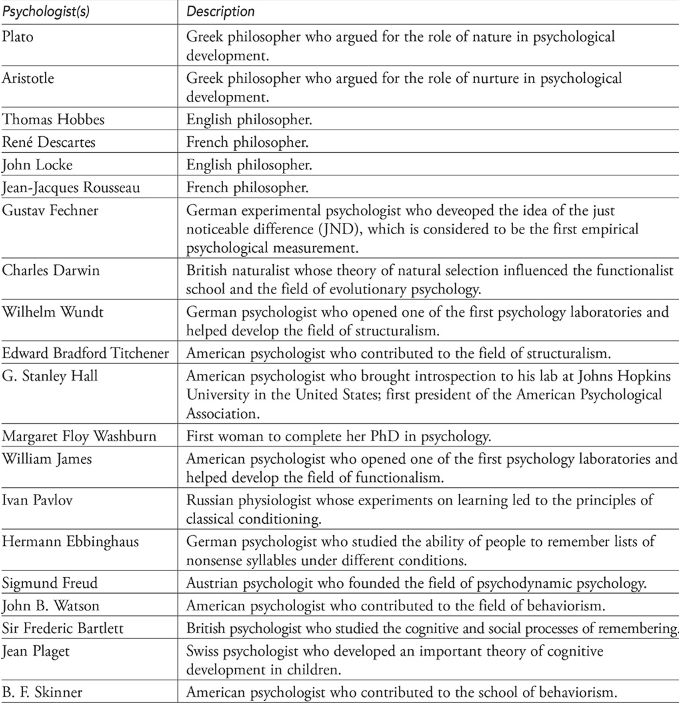

Leading Psychologists

Structuralism

In 1879, Wilhelm Wundt founded scientific psychology by founding a laboratory in Leipzig, Germany, to study immediate conscious sensation.

He taught his associates and observers to introspectively analyze their sensory experiences (inward-looking).

Replicating results under different conditions was his requirement.

Wundt used trained introspection to study the mind's structure and identify consciousness's basic elements—sensations, feelings, and images.

G. Stanley Hall founded the American Psychological Association, founded a psychology lab using introspection at Johns Hopkins University, and became its first president.

Edward Titchener brought introspection to his Cornell University lab, analyzed consciousness into its basic elements, and investigated how they are related.

Structuralism included Wundt, Hall, and Titchener.

Titchener's first graduate student and first psychology PhD was Margaret Floy Washburn.

Functionalism

American psychologist William James thought structuralists were asking the wrong questions.

James studied behavioral functions.

He believed humans actively processed sensations and actions.

James, James Cattell, and John Dewey were Functionalist psychologists who studied mental testing, child development, and education.

Functionalists used various methods to apply psychological findings to practical situations and study how mental operations adapt to the environment (stream of consciousness).

Behaviorism and applied psychology followed functionalism.

First female American Psychological Association president Mary Whiton Calkins studied psychology under James at Harvard.

Her self-psychology reconciled structural and functional psychology.

Principal Approaches to Psychology

Behavioral Approach

The behavioral approach focuses on measuring and recording observable behavior in relation to the environment.

Behaviorists think behavior results from learning.

Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov trained dogs to salivate in response to the sound of a tone, demonstrating stimulus–response learning.

Pavlov’s experiments at the beginning of the 20th century paved the way for behaviorism, which dominated psychology in America from the 1920s to the 1960s.

Behaviorists examine the ABCs of behavior.

They analyze Antecedent environmental conditions that precede a behavior, look at the Behavior (the action to understand, predict, and/or control), and examine the Consequences that follow the behavior (its effect on the environment).

Psychoanalytic/Psychodynamic Approach

Sigmund Freud opposed behaviorists in Austria.

He talked with mental patients for long periods to reveal unconscious conflicts, motives, and defenses to improve self-knowledge.

Psychoanalytic theory explained mental disorders, personality, and motivation through unconscious internal conflicts.

Freud believed that early life experiences shape personality and that the unconscious is the source of desires, thoughts, and memories.

Psychodynamic psychoanalysis includes Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Karen Horney, Heinz Kohut, and others.

Humanistic Approach

In contrast to behaviorists and psychoanalysts, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and other psychologists believed that humans have unique behavior.

Free will and personal growth shape behavior and thought.

Humanists value feelings and believe people are naturally positive and growth-seeking. Humanists interview people to solve their own problems.

Evolutionary Approach

An offshoot of the biological approach, evolutionary psychologists, returning to Darwin’s Theory of Natural Selection, explain behavior patterns as adaptations naturally selected because they increase reproductive success.

Cognitive Approach

Psychologists could study cognition—thinking and memory—again thanks to technology.

Cognitive psychologists emphasize receiving, storing, and processing information, thinking and reasoning, and language to understand human behavior.

Jean Piaget's cognitive development research influenced preschool and primary education.

Sociocultural Approach

Travel and the economy globalized in the second half of the 20th century, increasing cross-cultural interactions.

Psychologists found that different cultures interpret gestures, body language, and speech differently.

Psychologists studied social and environmental factors affecting cultural differences in behavior.

The sociocultural approach examines cultural differences to understand, predict, and control behavior.

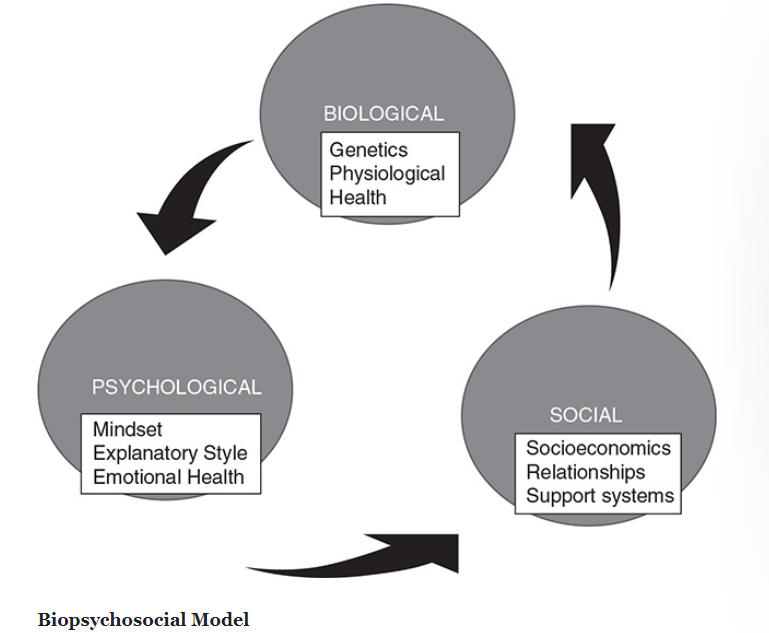

Biopsychosocial Model

Psychologists who use techniques and adopt ideas from a variety of approaches are considered eclectic.

The biopsychosocial model integrates biological processes, psychological factors, and social forces to provide a more complete picture of behavior and mental processes.

The model is a unifying theme in modern psychology drawing from and interacting with the seven approaches to explain behavior.

Domains of Psychology

Research and applied psychologists deal with a huge number of topics.

Topics can be grouped into broad categories known as domains.

Psychologists specializing in different domains identify themselves with many labels.

Clinical psychologists evaluate and treat mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders.

Clinical psychologists treat people with temporary psychological crises like grief, addiction, or social issues and those with chronic psychiatric disorders.

Clinical psychologists can specialize in children, the elderly, or specific disorders or work with a wide range of populations. Hospitals, community health centers, and private practice employ them.

Counseling psychologists help people adapt to change or make changes in their lifestyle.

Counseling psychologists are similar to clinical psychologists, but they focus more on lifestyle changes than psychological disorders.

Schools, universities, community mental health centers, and private practice employ these psychologists.

Developmental psychologists study psychological development throughout the life span.

They study intellectual, social, emotional, and moral development.

Some specialize in adolescence or geriatrics.

Developmental psychologists work in schools, daycare centers, social service agencies, and senior and geriatric facilities.

Educational psychologists focus on how effective teaching and learning take place.

They study human learning and create materials and strategies to improve it.

Universities, labs, and publishers employ educational psychologists.

Forensic psychologists apply psychological principles to legal issues.

They are concerned with the numerous facets of the law, such as determining a defendant’s competence to stand trial, or whether a victim has suffered psychological or neurological trauma.

Health/positive psychologists concentrate on biological, psychological, and social factors involved in health and illness.

They focus on psychology's role in health promotion and illness prevention and treatment.

This may include creating and promoting programs to help people quit smoking, diet, manage stress, and exercise.

Hospitals, rehabilitation centers, public health agencies, and private practice employ them.

Industrial/organizational psychologists aim to improve productivity and the quality of work life by applying psychological principles and methods to the workplace.

They manage organizational efficiency through human resources.

Organizational psychology emphasizes employee well-being and development, while industrial psychology emphasizes performance appraisals, job design, and selection and training.

Business, factories, and research facilities employ I/O psychologists.

Neuropsychologists explore the relationships between brain/nervous systems and behavior.

Biological psychologists, biopsychologists, behavioral geneticists, physiological psychologists, and behavioral neuroscientists are neuropsychologists.

They study biochemical mechanisms, brain structure and function, and emotional chemical and physical changes.

They can diagnose and treat brain and nervous system dysfunction-related behavior.

Hospitals have most doctoral and postdoctoral positions.

Psychometricians, sometimes called psychometric psychologists or measurement psychologists, focus on methods for acquiring and analyzing psychological data.

Psychometrists can create and modify intelligence, personality, and aptitude tests.

They may help psychology and other researchers design and interpret experiments.

They work in universities, testing centers, research firms, and government agencies.

Social psychologists focus on how a person’s mental life and behavior are shaped by interactions with other people.

They study how others influence our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Hospitals, federal agencies, and businesses are hiring social psychologists for applied research.

Experimental Method

The Controlled Experiment

The laboratory tests hypotheses, predictions of how two or more factors are likely to be related.

Variables are factors with multiple values.

In a scientific experiment, the researcher controls a variable and observes the response.

The researcher manipulates the independent variable (IV).

The dependent variable (DV) is the factor that may change as a result of manipulating the independent variable.

The researcher can draw the conclusion that the change in the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable if the dependent variable changes when only the independent variable is changed.

The independent variable causes the dependent variable.

Only a controlled experiment can prove cause-and-effect.

The population includes all the individuals in the group to which the study applies

Sample: a subgroup of the population.

Random selection can be achieved by putting all the names in a hat and picking out a specified number of names, by alphabetizing the roster of enrollees and choosing every fifth name, or by using a table of random numbers to choose participants.

Experimental group: receives the treatment

Control group: does not receive the treatment.

Between-subjects design: The participants in the experimental and control groups are different individuals.

Random assignment of participants to the experimental and control groups minimizes the existence of preexisting differences between the two groups.

Confounding variables: Differences between the experimental group and the control group other than those resulting from the independent variable.

Subjects: attend the same two sessions upon which the quiz is based.

Operational definition describes the specific procedure used to determine the presence of a variable.

Eliminating Confounding Variables

Experimenter bias (also called the experimenter expectancy effect) is a phenomenon that occurs when a researcher’s expectations or preferences about the outcome of a study influence the results obtained.

Demand characteristics: The clues participants discover about the purpose of the study, including rumors they hear about the study suggesting how they should respond.

Single-blind procedure, a research design in which the participants don’t know which treatment group—experimental or control—they are in.

Double-blind procedure, a research design in which neither the experimenter nor the participants know who is in the experimental group and who is in the control group.

Placebo: The imitation pill, injection, patch, or other treatment

Placebo effect is now used to describe any cases when experimental participants change their behavior in the absence of any kind of experimental manipulation.

Within-subjects design: A research design that uses each participant as his or her own control.

Counterbalancing, a procedure that assigns half the subjects to one of the treatments first and the other half of the subjects to the other treatment first.

Quasi-Experimental Research: Quasi-experimental research designs are similar to controlled experiments, but participants are not randomly assigned.

Correlational Research: Correlational methods look at the relationship between two variables without establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

The goal is to determine to what extent one variable predicts the other.

Naturalistic Observation: Naturalistic observation is carried out in the field where naturally occurring behavior can be observed.

Naturalistic observation studies gather descriptive information about typical behavior of people or animals without manipulating any variables.

Survey Method: researchers use questionnaires or interviews to ask a large number of people questions about their behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes.

Retrospective or ex post facto studies look at an effect and seek the cause.

Test Method: Tests are procedures used to measure attributes of individuals at a particular time and place.

Like surveys, tests can be used to gather huge amounts of information relatively quickly and cheaply.

Results of tests can be used for correlational analysis or for generating ideas for other research.

Reliability is consistency or repeatability.

Validity is the extent to which an instrument measures or predicts what it is supposed to.

Case Study: is an in-depth examination of a specific group or single person that typically includes interviews, observations, and test scores.

Elementary Statistics: Statistics is a field that involves the analysis of numerical data about representative samples of populations.

A large amount of data can be collected in research studies.

Descriptive Statistics: Numbers that summarize a set of research data obtained from a sample.

Frequency distribution, an orderly arrangement of scores indicating the frequency of each score or group of scores.

Histogram—a bar graph from the frequency distribution

Frequency polygon—a line graph that replaces the bars with single points and connects the points with a line.

Measures of Central Tendency

Measures of central tendency describe the average or most typical scores for a set of research data or distribution.

The mode is the most frequently occurring score in a set of research data. If two scores appear most frequently, the distribution is bimodal; if three or more scores appear most frequently, the distribution is multimodal.

The median is the middle score when the set of data is ordered by size.

The mean is the arithmetic average of the set of scores.

The normal distribution or normal curve is a symmetric, bell-shaped curve that represents data about how many human characteristics are dispersed in the population.

Distributions where most of the scores are squeezed into one end are skewed.

Measures of Variability

Variability describes the spread or dispersion of scores for a set of research data or distribution.

The range is the largest score minus the smallest score.

Variance and standard deviation (SD) indicate the degree to which scores differ from each other and vary around the mean value for the set.

Correlation

Scores can be reported in different ways.

One example is the standard score or z score.

Standard scores enable psychologists to compare scores that are initially on different scales.

Percentile score, indicates the percentage of scores at or below a particular score.

A statistical measure of the degree of relatedness or association between two sets of data, X and Y, is called the correlation coefficient.

The strength and direction of correlations can be illustrated graphically in scattergrams or scatterplots in which paired X and Y scores for each subject are plotted as single points on a graph.

Inferential Statistics

Inferential statistics are used to interpret data and draw conclusions.

They tell psychologists whether or not they can generalize from the chosen sample to the whole population, if the sample actually represents the population.

Statistical significance (p) is a measure of the likelihood that the difference between groups results from a real difference between the two groups rather than from chance alone.

Meta-analysis provides a way of statistically combining the results of individual research studies to reach an overall conclusion.

Ethical Guidelines

The American Psychological Association (APA) lists ethical principles and code of conduct for the scientific, educational, or professional roles for all psychologists.

They include psychology practice, research, teaching, and trainee supervision.

They also include all aspects of their performance in public service, policy development, social intervention, and development and conduction of assessments, to name but a few.

The code applies to all communications, including phone, social media, and in-person.

Discuss intellectual property frankly: The “publish-or-perish” mindset can lead to trouble when it comes to determining credit for authorship.

The best way to avoid disagreements, according to the APA, is to discuss these issues openly at the start of a working relationship, even though many people often feel uncomfortable about such topics.

Be conscious of multiple roles: This includes avoiding relationships that could negatively affect professional performance or exploit or harm others.

Participation in a study should be voluntary, and not coerced or influenced as part of a grade, raise, or promotion.

Follow informed consent rules such as IRBs, which ensure that individuals are voluntarily participating in the research with full knowledge of relevant risks and benefits.

The purpose, expected duration, and procedures of the research.

Their rights to decline to participate and withdraw from the research once it has begun, as well as consequences, if any, of doing so.

Factors that might influence their willingness to participate, such as possible risks, discomfort, or adverse effects.

Any possible research benefits.

Limits of confidentiality and when that confidentiality must be broken.

Incentives for participation, if any.

Unit 2: Biological Bases of Behavior

Techniques to Learn About Structure and Function

Paul Broca (1861) performed an autopsy on the brain of a patient, nicknamed Tan, who had lost the capacity to speak, although his mouth and his vocal cords weren’t damaged and he could still understand language.

Tan’s brain showed deterioration of part of the frontal lobe of the left cerebral hemisphere, as did the brains of several similar cases.

This connected destruction of the part of the left frontal lobe known as Broca’s area to loss of the ability to speak, known as expressive aphasia.

Carl Wernicke similarly found another brain area involved in understanding language in the left temporal lobe.

Destruction of Wernicke’s area results in loss of the ability to comprehend written and spoken language, known as receptive aphasia.

Lesions, precise destruction of brain tissue, enabled more systematic study of the loss of function resulting from surgical removal (also called ablation), cutting of neural connections, or destruction by chemical applications.

Studies by Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga of patients with these “split brains” have revealed that the left and right hemispheres do not perform exactly the same functions (brain lateralization) that the hemispheres specialize in.

Computerized axial tomography (CAT or CT) creates a computerized image using X-rays passed through various angles of the brain showing two-dimensional “slices” that can be arranged to show the extent of a lesion.

In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a magnetic field and pulses of radio waves cause the emission of faint radio frequency signals that depend upon the density of the tissue.

Measuring Brain Function

An EEG (electroencephalogram) is an amplified tracing of brain activity produced when electrodes positioned over the scalp transmit signals about the brain’s electrical activity (“brain waves”) to an electroencephalograph machine.

The amplified tracings are called evoked potentials when the recorded change in voltage results from a response to a specific stimulus presented to the subject.

Positron emission tomography (PET) produces color computer graphics that depend on the amount of metabolic activity in the imaged brain region.

Functional MRI (fMRI) shows the brain at work at higher resolution than the PET scanner.

Changes in oxygen in the blood of an active brain area alters its magnetic qualities, which is recorded by the fMRI scanner.

A magnetic source image (MSI), which is produced by magnetoencephalography (MEG scan), is similar to an EEG, but the MEG scans are able to detect the slight magnetic field caused by the electric potentials in the brain.

Organization of Your Nervous System

Central nervous system: consists of your brain and your spinal cord.

Peripheral nervous system : includes two major subdivisions: your somatic nervous system and your autonomic nervous system.

Your peripheral nervous system lies outside the midline portion of your nervous system carrying sensory information to and motor information away from your central nervous system via spinal and cranial nerves.

Somatic nervous system: has motor neurons that stimulate skeletal (voluntary) muscle.

Autonomic nervous system: has motor neurons that stimulate smooth (involuntary) and heart muscle.

Your autonomic nervous system is subdivided into the antagonistic sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system.

Sympathetic stimulation results in responses that help your body deal with stressful events including dilation of your pupils, release of glucose from your liver, dilation of bronchi, inhibition of digestive functions, acceleration of heart rate, secretion of adrenaline from your adrenal glands, acceleration of breathing rate, and inhibition of secretion of your tear glands.

Parasympathetic stimulation calms your body following sympathetic stimulation by restoring digestive processes (salivation, peristalsis, enzyme secretion), returning pupils to normal pupil size, stimulating tear glands, and restoring normal bladder contractions.

Spinal cord, protected by membranes called meninges and your spinal column of bony vertebrae, starts at the base of your back and extends upward to the base of your skull where it joins your brain.

The Brain

According to one evolutionary model (triune brain), the human brain has three major divisions, overlapping layers with the most recent neural systems nearest the front and top.

The reptilian brain, which maintains homeostasis and instinctive behaviors, roughly corresponds to the brainstem, which includes the medulla, pons, and cerebellum.

The old mammalian brain roughly corresponds to the limbic system that includes the septum, hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate cortex, hypothalamus, and the thalamus, which are all important in controlling emotional behavior, some aspects of memory, and vision.

The new mammalian brain or neocortex, synonymous with the cerebral cortex, accounts for about 80 percent of brain volume and is associated with the higher functions of judgment, decision making, abstract thought, foresight, hindsight and insight, language, and computing, as well as sensation and perception.

The surface of your cortex has peaks called gyri and valleys called sulci, which form convolutions that increase the surface area of your cortex.

Deeper valleys are called fissures.

The last evolutionary development of the brain is the localization of functions on different sides of your brain.

Localization and Lateralization of the Brain’s Function

Association areas are regions of the cerebral cortex that do not have specific sensory or motor functions but are involved in higher mental functions, such as thinking, planning, remembering, and communicating.

Medulla oblongata—regulates heart rhythm, blood flow, breathing rate, digestion, vomiting.

Pons—includes portion of reticular activating system or reticular formation critical for arousal and wakefulness; sends information to and from medulla, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex.

Cerebellum—controls posture, equilibrium, and movement.

Basal ganglia—regulates initiation of movements, balance, eye movements, and posture, and functions in processing of implicit memories.

Thalamus—relays visual, auditory, taste, and somatosensory information to/from appropriate areas of cerebral cortex.

Hypothalamus—controls feeding behavior, drinking behavior, body temperature, sexual behavior, threshold for rage behavior, activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems, and secretion of hormones of the pituitary.

Hippocampus—enables formation of new long-term memories.

Cerebral cortex—center for higher-order processes such as thinking, planning, judgment; receives and processes sensory information and directs movement.

Plasticity: Although specific regions of the brain are associated with specific functions, if one region is damaged, the brain can reorganize to take over its function.

Structure and Function of the Neuron

Glial cells guide the growth of developing neurons, help provide nutrition for and get rid of wastes of neurons, and form an insulating sheath around neurons that speeds conduction.

The neuron is the basic unit of structure and function of your nervous system.

The cell body (a.k.a. cyton or soma) contains cytoplasm and the nucleus, which directs synthesis of such substances as neurotransmitters.

The dendrites are branching tubular processes capable of receiving information.

The axon emerges from the cyton as a single conducting fiber (longer than a dendrite) that branches and ends in tips called terminal buttons, axon terminals, or synaptic knobs.

The axon is usually covered by an insulating myelin sheath (formed by glial cells).

Neurogenesis, the growth of new neurons, takes place throughout life.

Neurotransmitters are chemicals stored in structures of the terminal buttons called synaptic vesicles.

Dopamine stimulates the hypothalamus to synthesize hormones and affects alertness and movement.

Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter involved in information processing throughout the cortex and especially memory formation in the hippocampus.

Serotonin is associated with sexual activity, concentration and attention, moods, and emotions.

Opioid peptides such as endorphins are often considered the brain’s own painkillers. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibits firing of neurons.

Norepinephrine, also known as noradrenaline, is associated with attentiveness, sleeping, dreaming, and learning.

Agonists may mimic a neurotransmitter and bind to its receptor site to produce the effect of the neurotransmitter.

Antagonists block a receptor site, inhibiting the effect of the neurotransmitter or agonist.

Neuron Functions

The neuron at rest is more negative inside the cell membrane relative to outside of the membrane.

The neuron’s resting potential results from the selective permeability of its membrane and the presence of electrically charged particles called ions near the inside and outside surfaces of the membrane in different concentrations.

When sufficiently stimulated (to threshold), a net flow of sodium ions into the cell causes a rapid change in potential across the membrane, known as the action potential.

If stimulation is not strong enough, your neuron doesn’t fire. The strength of the action potential is constant whenever it occurs.

This is the all-or-none principle.

The wave of depolarization and repolarization is passed along the axon to the terminal buttons, which release neurotransmitters.

Spaces between segments of myelin are called nodes of Ranvier.

When the axon is myelinated, conduction speed is increased since depolarizations jump from node to node.

This is called saltatory conduction.

Excitatory, the neurotransmitters cause the neuron on the other side of the synapse to generate an action potential (to fire); other synapses are inhibitory, reducing or preventing neural impulses.

Reflex Action

Reflex involves impulse conduction over a few (perhaps three) neurons. The path is called a reflex arc.

Sensory or afferent neurons transmit impulses from your sensory receptors to the spinal cord or brain.

Interneurons, located entirely within your brain and spinal cord, intervene between sensory and motor neurons.

Motor or efferent neurons transmit impulses from your sensory or interneurons to muscle cells that contract or gland cells that secrete.

Muscle and gland cells are called effectors.

The Endocrine System

Your endocrine system consists of glands that secrete chemical messengers called hormones into your blood.

The hormones travel to target organs where they bind to specific receptors.

Endocrine glands include the pineal gland, hypothalamus, and pituitary gland in your brain; the thyroid and parathyroids in your neck; the adrenal glands atop your kidneys; pancreas near your stomach; and either testes or ovaries.

Pineal Gland: endocrine gland in brain that produces melatonin that helps regulate circadian rhythms and is associated with seasonal affective disorder.

Hypothalamus: portion of brain part that acts as endocrine gland and produces hormones that stimulate (releasing factors) or inhibit secretion of hormones by the pituitary.

Pituitary Gland: endocrine gland in brain that produces stimulating hormones, which promote secretion by other glands including TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone); ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone), which stimulates the adrenal glands; FSH (follicle stimulating hormone), which stimulates egg or sperm production; ADH (antidiuretic hormone) to help retain water in your body; and HGH (human growth hormone).

Thyroid Gland: endocrine gland in neck that produces thyroxine, which stimulates and maintains metabolic activities.

Parathyroids: endocrine glands in neck that produce parathyroid hormone, which helps maintain calcium ion level in blood necessary for normal functioning of neurons.

Adrenal Glands: endocrine glands atop kidneys

Pancreas: gland near stomach that secretes the hormones insulin and glucagon, which regulate blood sugar that fuels all behavioral processes.

Ovaries and Testes: gonads in females and males, respectively, that produce hormones necessary for reproduction and development of secondary sex characteristics.

Genetics and Evolutionary Psychology

The nature-nurture controversy deals with the extent to which heredity and the environment each influence behavior.

Evolutionary psychologists study how natural selection favored behaviors that contributed to survival and the spread of our ancestors’ genes and may currently contribute to our survival into the next generations.

Evolutionary psychologists look at universal behaviors shared by all people.

Genetics and Behavior

Behavioral geneticists study the role played by our genes and our environment in mental ability, emotional stability, temperament, personality, interests, and so forth; they look at the causes of our individual differences.

Identical twins are two individuals who share all of the same genes/heredity because they develop from the same fertilized egg or zygote; they are monozygotic twins.

Fraternal twins are siblings that share about half of the same genes because they develop from two different fertilized eggs or zygotes; they are dizygotic twins.

Heritability is the proportion of variation among individuals in a population that is due to genetic causes.

Transmission of Hereditary Characteristics

Each DNA segment of a chromosome that determines a trait is a gene.

Chromosomes carry information stored in genes to new cells during reproduction.

Normal human body cells have 46 chromosomes, except for eggs and sperms that have 23 chromosomes.

Turner syndrome have only one X sex chromosome (XO).

Klinefelter’s syndrome arise from an XXY zygote.

Males with Klinefelter’s tend to be passive. The presence of three copies of chromosome 21 results in the expression of Down syndrome.

The genetic makeup for a trait of an individual is called its genotype.

The expression of the genes is called its phenotype.

If the genes are different, the expressed gene is called the dominant gene; the hidden gene is the recessive gene.

Tay-Sachs syndrome produces progressive loss of nervous function and death in a baby.

Albinism arises from a failure to synthesize or store pigment and also involves abnormal nerve pathways to the brain, resulting in quivering eyes and the inability to perceive depth or three-dimensionality with both eyes.

Phenylketonuria (PKU) results in severe, irreversible brain damage unless the baby is fed a special diet low in phenylalanine within 30 days of birth; the infant lacks an enzyme to process this amino acid, which can build up and poison cells of the nervous system.

Huntington’s disease is an example of a dominant gene defect that involves degeneration of the nervous system.

A form of familial Alzheimer’s disease has been attributed to a gene on chromosome 21, but not all cases of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with that gene.

Levels of Consciousness

Preconscious is the level of consciousness that is outside of awareness but contains feelings and memories that you can easily bring into conscious awareness.

Nonconscious is the level of consciousness devoted to processes completely inaccessible to conscious awareness, such as blood flow, filtering of blood by kidneys, secretion of hormones, and lower-level processing of sensations, such as detecting edges, estimating size and distance of objects, recognizing patterns, and so forth.

Unconscious, sometimes called the subconscious, is the level of consciousness that includes often unacceptable feelings, wishes, and thoughts not directly available to conscious awareness.

Dual processing refers to processing information on conscious and unconscious levels at the same time.

Unconsciousness is characterized by loss of responsiveness to the environment, resulting from disease, trauma, or anesthesia.

Sleep and Dreams

Hypothalamus: systematically regulates changes in your body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, blood sugar levels, hormonal levels, and activity levels over the course of about a day.

Circadian rhythm is a natural, internal process that regulates the sleep-wake cycle and repeats roughly every 24 hours.

It's also known as your body’s clock — it influences when you fall asleep and wake up.

Your circadian rhythm mainly responds to light and darkness in your environment.

Sleep is a complex combination of states of consciousness, each with its own level of consciousness, awareness, responsiveness, and physiological arousal.

Electroencephalograms (EEGs) can be recorded with electrodes on the surface of the skull.

Hypnagogic state; you feel relaxed, fail to respond to outside stimuli, and begin the first stage of sleep, Non-REM-1.

EEGs of NREM-1 sleep show theta waves, which are higher in amplitude and lower in frequency than alpha waves.

As you pass into NREM-2, your EEG shows high-frequency bursts of brain activity (called sleep spindles) and K complexes.

NREM-3 sleep EEG shows very high amplitude and very low-frequency delta waves.

REM sleep (Rapid Eye Movement sleep) about 90 minutes after falling asleep.

Nightmares are frightening dreams that occur during REM sleep.

Lucid dreaming, the ability to be aware of and direct one’s dreams, has been used to help people make recurrent nightmares less frightening.

Interpretation of Dreams

Freud tried to analyze dreams to uncover the unconscious desires (many of them sexual) and fears disguised in dreams.

He considered the remembered story line of a dream its manifest content, and the underlying meaning its latent content.

Psychiatrists Robert McCarley and J. Alan Hobson proposed another theory of dreams called the activation-synthesis theory.

Pons generates bursts of action potentials to the forebrain, which is activation.

Sleep Disorders

Insomnia is the inability to fall asleep and/or stay asleep.

Narcolepsy is a condition in which an awake person suddenly and uncontrollably falls asleep, often directly into REM sleep.

Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder characterized by temporary cessations of breathing that awaken the sufferer repeatedly during the night.

Night terrors are most frequently childhood sleep disruptions from the deepest part of NREM-3 (formerly referred to as stage 4) sleep characterized by a bloodcurdling scream and intense fear.

Sleepwalking, also called somnambulism, is also most frequently a childhood sleep disruption that occurs during deep NREM-3 sleep characterized by trips out of bed or carrying on complex activities.

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness characterized by deep relaxation and heightened suggestibility.

Under hypnosis, subjects can change aspects of reality and let those changes influence their behavior.

Hypnotized individuals may feel as if their bodies are floating or sinking; see, feel, hear, smell, or taste things that are not there; lose sense of touch or pain; be made to feel like they are passing back in time; act as if they are out of their own control; and respond to suggestions by others.

According to the dissociation theory, hypnotized individuals experience two or more streams of consciousness cut off from each other.

Meditation

Meditation is a set of techniques used to focus concentration away from thoughts and feelings in order to create calmness, tranquility, and inner peace.

Meditation is popular in Asia, where Zen Buddhists meditate.

EEGs of meditators show alpha waves characteristic of relaxed wakefulness.

Drugs

Psychoactive drugs are chemicals that can pass through the blood-brain barrier into the brain to alter perception, thinking, behavior, and mood, producing a wide range of effects from mild relaxation or increased alertness to vivid hallucinations.

Psychological dependence develops when the person has an intense desire to achieve the drugged state in spite of adverse effects.

Tolerance: decreasing responsivity to a drug

Physiological dependence or addiction develops when changes in brain chemistry from taking the drug necessitate taking the drug again to prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Withdrawal symptoms include intense craving for the drug and effects opposite to those the drug usually induces.

Depressants are psychoactive drugs that reduce the activity of the central nervous system and induce relaxation.

Depressants include sedatives, such as barbiturates, tranquilizers, and alcohol.

Narcotics are analgesics (pain reducers) that work by depressing the central nervous system.

They can also depress the respiratory system.

Stimulants are psychoactive drugs that activate motivational centers and reduce activity in inhibitory centers of the central nervous system by increasing activity of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine neurotransmitter systems.

Hallucinogens, also called psychedelics, are a diverse group of psychoactive drugs that alter moods, distort perceptions, and evoke sensory images in the absence of sensory input.

Unit 3: Sensation and Perception

Thresholds

Absolute threshold, the weakest level of a stimulus that can be correctly detected at least half the time.

According to signal detection theory, there is no actual absolute threshold because the threshold changes with a variety of factors, including fatigue, attention, expectations, motivation, and emotional distress.

Subliminal stimulation is the receipt of messages that are below one’s absolute threshold for conscious awareness.

Subliminal messages can have a momentary, subtle effect on thinking.

Difference threshold—the minimum difference between any two stimuli that a person can detect 50 percent of the time—has been reached.

According to Weber’s law, which was quantified by Gustav Fechner, difference thresholds increase in proportion to the size of the stimulus.

Sensory adaptation permits you to focus your attention on informative changes in your environment without being distracted by irrelevant data such as odors or background noises.

Transmission of Sensory Information

Transduction refers to the transformation of stimulus energy to the electrochemical energy of neural impulses.

Perception is the process of selecting, organizing, and interpreting sensations, enabling you to recognize meaningful objects and events.

Vision

Since most people rely on sight, psychologists study visual perception.

The retina's cones and rods, the brain's pathways, and the visual cortex in the occipital lobes are where visual sensation and perception begin.

Your retinal image is upside-down and incomplete. Your brain instantly corrects the upside-down image.

Visual Pathway

Millions of rods and cones are the photoreceptors that convert light energy to electrochemical neural impulses.

Your eyeball is protected by an outer membrane composed of the sclera, tough, white, connective tissue that contains the opaque white of the eye, and the cornea, the transparent tissue in the front of your eye.

Rays of light entering your eye are bent first by the curved transparent cornea, pass through the liquid aqueous humor and the hole through your muscular iris called the pupil, are further bent by the lens, and pass through your transparent vitreous humor before focusing on the rods and cones in the back of your eye.

Nearsighted if too much curvature of the cornea and/or lens focuses an image in front of the Farsighted if too little curvature of the cornea and/or lens focuses the image behind the retina so distant objects are seen more clearly than nearby ones.

Astigmatism is caused by an irregularity in the shape of the cornea and/or the lens.

Dark adaptation: When it suddenly becomes dark, your gradual increase in sensitivity to the low level of light

Bipolar cells: Rods and cones both synapse with a second layer of neurons in front of them in your retina.

Bipolar cells transmit impulses to another layer of neurons in front of them in your retina, the ganglion cells.

Blind spot: Where the optic nerve exits the retina, there aren’t any rods or cones, so the part of an image that falls on your retina in that area is missing.

Feature detectors: The thalamus then routes information to the primary visual cortex of your brain, where specific neurons

Parallel processing: Simultaneous processing of stimulus elements

Color Vision

The colors of objects you see depend on the wavelengths of light reflected from those objects to your eyes.

Light is the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The colors vary in wavelength from the longest (red) to the shortest (violet).

A wavelength is the distance from the top of one wave to the top of the next wave.

In the 1800s, Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz accounted for color vision with the trichromatic theory that three different types of photoreceptors are each most sensitive to a different range of wavelengths.

People with three different types of cones are called trichromats; with two different types, dichromats; and with only one, monochromats.

People who are color-blind lack a chemical usually produced by one or more types of cones.

According to Ewald Hering’s opponent-process theory, certain neurons can be either excited or inhibited, depending on the wavelength of light, and complementary wavelengths have opposite effects.

Hearing (Audition)

Hearing is the primary sensory modality for human language.

Amplitude is measured in logarithmic units of pressure called decibels (dB).

Pitch: determine the highness or lowness of the sound

You can tell the difference between the notes of the same pitch and loudness played on a flute and on a violin because of a difference in the purity of the wave form or mixture of the sound waves, a difference in timbre.

Ear

The pinna, auditory canal, and tympanum make up your outer ear.

The eardrum vibrates with sound waves from the outer ear.

The middle ear's ossicles—the hammer, anvil, and stirrup—vibrate.

The vibrating stirrup hits the inner ear's cochlea oval window.

A basilar membrane with hair cells bends vibrations and converts them to neural impulses.

Auditory neurons form the auditory nerve by synapsing with hair cells.

The auditory nerve sends sound to the temporal lobe auditory cortex via the medulla, pons, and thalamus.

The medulla and pons cross most auditory nerve fibers, so your auditory cortex receives input from both ears, but contralateral input dominates.

The process by which you determine the location of a sound is called sound localization.

According to Georg von Békésy’s place theory, the position on the basilar membrane at which waves reach their peak depends on the frequency of a tone.

According to frequency theory, the rate of the neural impulses traveling up the auditory nerve matches the frequency of a tone, enabling you to sense its pitch.

Conduction deafness is a loss of hearing that results when the eardrum is punctured or any of the ossicles lose their ability to vibrate.

Nerve (sensorineural) deafness results from damage to the cochlea, hair cells, or auditory neurons.

Somatosensation as a general term for four classes of tactile sensations: touch/pressure, warmth, cold, and pain.

Itching results from repeated gentle stimulation of pain receptors, a tickle results from repeated stimulation of touch receptors, and the sensation of wetness results from simultaneous stimulation of adjacent cold and pressure receptors.

Touch is necessary for normal development and promotes a sense of well-being.

Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall’s gate-control theory attempts to explain the experience of pain.

You experience pain only if the pain messages can pass through a gate in the spinal cord on their route to the brain.

Body Senses

Kinesthesis is the system that enables you to sense the position and movement of individual parts of your body.

Sensory receptors for kinesthesis are nerve endings in your muscles, tendons, and joints.

Your vestibular sense is your sense of equilibrium or body orientation.

Chemical Senses

Gustation (taste) and olfaction (smell) are called chemical senses because the stimuli are molecules.

Your chemical senses are important systems for warning and attraction.

You won’t eat rotten eggs or drink sour milk, and you can smell smoke before a sensitive household smoke detector.

Taste receptor cells are most concentrated not only on your tongue in taste buds embedded in tissue called fungiform papillae, but are also on the roof of your mouth and the opening of your throat.

Tasters have an average number of taste buds, nontasters have fewer taste buds, and supertasters have the most.

Supertasters are more sensitive than others to bitter, spicy foods and alcohol, which they find unpleasant.

Attention

Selective attention: You focus your awareness on only a limited aspect of all you are capable of experiencing.

Bottom-up processing: your sensory receptors detect external stimulation and send these raw data to the brain for analysis.

Top-down processing takes what you already know about particular stimulation, what you remember about the context in which it usually appears, and how you label and classify it, to give meaning to your perceptions.

Visual capture: Where you perceive a conflict among senses, vision usually dominates.

Gestalt Organizing Principles of Form Perception

Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Kohler studied how the mind organizes sensations into perceptions of meaningful patterns or forms, called a gestalt in German.

Phi phenomenon, which is the illusion of movement created by presenting visual stimuli in rapid succession.

Figure–ground relationship: The figure is the dominant object, and the ground is the natural and formless setting for the figure.

Proximity, the nearness of objects to each other, is an organizing principle.

Principle of closure states that we tend to fill in gaps in patterns.

The closure principle is not limited to vision.

Principle of similarity states that like stimuli tend to be perceived as parts of the same pattern.

Principle of continuity or continuation states that we tend to group stimuli into forms that follow continuous lines or patterns.

Optical or visual illusions are discrepancies between the appearance of a visual stimulus and its physical reality.

Visual illusions, such as reversible figures, illustrate the mind’s tendency to separate figure and ground in the absence of sufficient cues for deciding which is which.

Depth Perception

Depth perception is the ability to judge the distance of objects.

Monocular cues are clues about distance based on the image of one eye, whereas binocular cues are clues about distance requiring two eyes.

Retinal disparity, which is the slightly different view the two eyes have of the same object because the eyes are a few centimeters apart.

Motion parallax involves images of objects at different distances moving across the retina at different rates.

Interposition or overlap can be seen when a closer object cuts off the view of part or all of a more distant one.

Relative size of familiar objects provides a cue to their distance when the closer of two same-size objects casts a larger image on your retina than the farther one.

Relative clarity can be seen when closer objects appear sharper than more distant, hazy objects.

Texture gradient provides a cue to distance when closer objects have a coarser, more distinct texture than faraway objects that appear more densely packed or smooth.

Relative height or elevation can be seen when the objects closest to the horizon appear to be the farthest from you.

Linear perspective provides a cue to distance when parallel lines, such as edges of sidewalks, seem to converge in the distance.

Relative brightness can be seen when the closer of two identical objects reflects more light to your eyes.

Optical illusions, such as the Müller-Lyer illusion and the Ponzo illusion, in which two identical horizontal bars seems to differ in length, may occur because distance cues lead one line to be judged as farther away than the other.

Perceptual Constancy

As a car approaches, you know that it’s not growing in size, even though the image it casts on your retina gets larger, because you impose stability on the constantly changing sensations you experience.

Three perceptual constancies are size constancy, by which an object appears to stay the same size despite changes in the size of the image it casts on the retina as it moves farther away or closer; shape constancy, by which an object appears to maintain its normal shape regardless of the angle from which it is viewed; and brightness constancy, by which an object maintains a particular level of brightness regardless of the amount of light reflected from it.

Perceptual Adaptation and Perceptual Set

If you repeated your actions, you probably reached the item quickly.

Blind people who become sighted can immediately distinguish colors and figure from ground, but it takes time to recognize shapes.

Cultural assumptions and beliefs affect visual perception.

You must be familiar with the object and have seen it in the distance to use relative size.

Culture and Experience

Your perceptual set or mental predisposition can influence what you perceive when you look at ambiguous stimuli.

Your perceptual set is determined by the schemas you form as a result of your experiences.

Schemas are concepts or frameworks that organize and interpret information.

Unit 4: Learning

Classical Conditioning

In classical conditioning: the subject learns to give a response it already knows to a new stimulus.

The subject associates a new stimulus with a stimulus that automatically and involuntarily brings about the response.

Stimulus is a change in the environment that elicits (brings about) a response.

Response: is a reaction to a stimulus.

Neutral stimulus (NS): initially does not elicit a response.

Unconditioned stimulus (UCS or US): reflexively, or automatically, brings about the unconditioned response (UCR or UR).

Conditioned stimulus (CS): is a NS at first, but when paired with the UCS, it elicits the conditioned response (CR).

Aversive conditioning: Conditioning involving an unpleasant or harmful unconditioned stimulus or reinforcer, such as this conditioning of Baby Albert.

Spontaneous recovery: Although not fully understood by behaviorists, sometimes the extinguished response will show up again later without the re-pairing of the UCS and CS.

Generalization: occurs when stimuli similar to the CS also elicit the CR without any training.

Discrimination occurs when only the CS produces the CR.

Higher-Order Conditioning: Higher-order conditioning, also called second-order or secondary conditioning, occurs when a well-learned CS is paired with an NS to produce a CR to the NS.

In this conditioning, the old CS acts as a UCS.

Operant Conditioning: In operant conditioning, an active subject voluntarily emits behaviors and can learn new behaviors.

The connection is made between the behavior and its consequence, whether pleasant or not.

Thorndike’s Instrumental Conditioning

Instrumental learning: is a type of learning that involves the acquisition and use of skills or strategies to achieve a specific goal. It can involve trial-and-error processes, imitation, reinforcement, modeling, memorization and more.

Law of Effect: states that behaviors followed by satisfying or positive consequences are strengthened (more likely to occur), while behaviors followed by annoying or negative consequences are weakened (less likely to occur).

B. F. Skinner’s Training Procedures

Positive reinforcement: or reward training, emission of a behavior or response is followed by a reinforcer that increases the probability that the response will occur again.

Premack principle: a more probable behavior can be used as a reinforcer for a less probable one.

Negative reinforcement: takes away an aversive or unpleasant consequence after a behavior has been given.

Punishment training: a learner’s response is followed by an aversive consequence.

Omission training: In this training procedure, a response by the learner is followed by taking away something of value from the learner.

Operant Aversive Conditioning

Aversive conditioning: is a type of learning in which an organism learns to associate an unpleasant stimulus with a particular behavior.

This type of conditioning works by creating an association between the behavior and some sort of punishment or discomfort, so that the organism will be less likely to do it again.

Avoidance behavior: takes away the aversive stimulus before it begins.

Reinforcers

Primary reinforcer: is something that is biologically important and, thus, rewarding.

Secondary reinforcer: is something neutral that, when associated with a primary reinforcer, becomes rewarding.

Generalized reinforcer: is a secondary reinforcer that can be associated with a number of different primary reinforcers.

Token economy: has been used extensively in institutions such as mental hospitals and jails.

Teaching a New Behavior

Shaping: positively reinforcing closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior, is an effective way of teaching a new behavior.

Chaining: is used to establish a specific sequence of behaviors by initially positively reinforcing each behavior in a desired sequence and then later rewarding only the completed sequence.

Schedules of Reinforcement

Continuous reinforcement: is the schedule that provides reinforcement every time the behavior is exhibited by the organism.

Partial reinforcement: schedules based on the number of desired responses are ratio schedules.

Interval schedules: Schedules based on time.

Fixed ratio: schedules reinforce the desired behavior after a specific number of responses have been made.

Fixed interval: schedules reinforce the first desired response made after a specific length of time.

Variable ratio: schedule, the number of responses needed before reinforcement occurs changes at random around an average.

Variable interval: schedule, the amount of time that elapses before reinforcement of the behavior changes.

fixed ratio schedule—know how much behavior for reinforcement

fixed interval schedule—know when behavior is reinforced

variable ratio schedule—how much behavior for reinforcement changes

variable interval schedule—when behavior for reinforcement changes

Cognitive Processes in Learning

Behaviorists included John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner.

Only observable behaviors, antecedents, and consequences were studied.

Since they couldn't measure thought processes, they ignored them.

They believed nurture shaped behavior (the environment).

The Contingency Model

Pavlov’s view of classical conditioning is called the contiguity model.

He believed that the close time between the CS and the US was most important for making the connection between the two stimuli and that the CS eventually substituted for the US.

Cognitivist Robert Rescorla: suggesting a contingency model of classical conditioning that the CS tells the organism that the US will follow.

Latent Learning: is defined as learning in the absence of rewards.

Insight is the sudden appearance of an answer or solution to a problem.

Social Learning: which occurs by watching the behavior of a model.

Biological Factors in Learning

Mirror neurons in the premotor cortex and other temporal and parietal lobes support observational learning.

Both doing and watching an action activates neurons.

These neurons convert the sight of someone else's action into the motor program you would use to do the same and feel similar emotions, the basis for empathy.

Preparedness Evolves

Conditioned taste aversion: an intense dislike and avoidance of a food because of its association with an unpleasant or painful stimulus through backward conditioning.

Preparedness: means that through evolution, animals are biologically predisposed to easily learn behaviors related to their survival as a species, and that behaviors contrary to an animal’s natural tendencies are learned slowly or not at all.

Instinctive drift: a conditioned response that drifts back toward the natural (instinctive) behavior of the organism.

Unit 5: Cognition

Models of Memory

Information Processing Model

Information processing model: compares our mind to a computer.

Encoded when our sensory receptors send impulses that are registered by neurons in our brain, similar to getting electronic information into our computer’s CPU (central processing unit) by keyboarding.

Store and retain the information in our brain for some period, ranging from a moment to a lifetime, similar to saving information in our computer’s hard drive.

Retrieved upon demand when it is needed, similar to opening up a document or application from the hard drive.

Donald Broadbent: modeled human memory and thought processes using a flowchart that showed competing information filtered out early, as it is received by the senses and analyzed in the stages of memory.

Attention: is the mechanism by which we restrict information.

Trying to attend to one task over another requires selective or focused attention.

We have great difficulty when we try to attend to two complex tasks at once requiring divided attention, such as listening to different conversations or driving and texting.

According to Anne Treisman’s feature integration theory, you must focus attention on complex incoming auditory or visual information in order to synthesize it into a meaningful pattern.

Levels-of-Processing Model

According to Fergus Craik and Robert Lockhart’s levels-of-processing theory: how long and how well we remember information depends on how deeply we process the information when it is encoded.

Shallow processing: we use structural encoding of superficial sensory information that emphasizes the physical characteristics, such as lines and curves, of the stimulus as it first comes in.

Semantic encoding: associated with deep processing, emphasizes the meaning of verbal input.

Deep processing: occurs when we attach meaning to information and create associations between the new memory and existing memories (elaboration).

Three-Stage Model

Atkinson–Shiffrin three-stage model of memory: describes three different memory systems characterized by time frames: sensory memory, short-term memory (STM), and long-term memory.

Sensory memory: visual or iconic memory that completely represents a visual stimulus lasts for less than a second, just long enough to ensure that we don’t see gaps between frames in a motion picture.

Auditory or echoic memory lasts for about 4 seconds, just long enough for us to hear a flow of information.

Selective attention: focusing of awareness on a specific stimulus in sensory memory, determines which very small fraction of information perceived in sensory memory is encoded into short-term memory.

Automatic processing: is unconscious encoding of information about space, time, and frequency that occurs without interfering with our thinking about other things.

Parallel processing: a natural mode of information processing that involves several information streams simultaneously.

Effortful processing: is encoding that requires our focused attention and conscious effort.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory (STM): can hold a limited amount of information for about 30 seconds unless it is processed further.

Chunk: can be a word rather than individual letters or a date rather than individual numbers.

Alan Baddeley’s: working memory model involves much more than chunking, rehearsal, and passive storage of information.

Working memory model: is an active three-part memory system that temporarily holds information and consists of a phonological loop, visuospatial working memory, and the central executive.

Long-Term Memory

Long-term memory (LTM): is the relatively permanent and practically unlimited capacity memory system into which information from short-term memory may pass.

Explicit memory: also called declarative memory, is our LTM of facts and experiences we consciously know and can verbalize.

Semantic memory of facts and general knowledge, and episodic memory of personally experienced events.

Implicit memory: also called non-declarative memory, is our LTM for skills and procedures to do things affected by previous experience without that experience being consciously recalled.

Procedural memories: are tasks that we perform automatically without thinking, such as tying our shoelaces or swimming.

Prospective memory: is our memory to perform a planned action or remembering to perform that planned action.

Organization of Memories

Hierarchies: are systems in which concepts are arranged from more general to more specific classes.

Concepts: can be simple or complex.

Prototypes: which are the most typical examples of the concept.

Semantic networks: are more irregular and distorted systems than strict hierarchies, with multiple links from one concept to others.

Dr. Steve Kosslyn: showed that we seem to scan a visual image of a picture (mental map) in our mind when asked questions.

Schemas: are preexisting mental frameworks that start as basic operations and then get more and more complex as we gain additional information.

Script: is a schema for an event.

Connectionism: theory states that memory is stored throughout the brain in connections between neurons, many of which work together to process a single memory.

Artificial intelligence (AI): have designed the neural network or parallel processing model that emphasizes the simultaneous processing of information, which occurs automatically and without our awareness.

Neural network: computer models are based on neuronlike systems, which are biological rather than artificially contrived computer codes; they can learn, adapt to new situations, and deal with imprecise and incomplete information.

Biology of Long-Term Memory

Long-term potentiation (or LTP): involves an increase in the efficiency with which signals are sent across the synapses within neural networks of long-term memories.

Flashbulb memory: a vivid memory of an emotionally arousing event, is associated with an increase of adrenal hormones triggering release of energy for neural processes and activation of the amygdala and the hippocampus involved in emotional memories.

The role of the thalamus in memory seems to involve the encoding of sensory memory into short-term memory.

The hippocampus, frontal and temporal lobes of the cerebral cortex, and other regions of the limbic system are involved in explicit long-term memory.

Anterograde amnesia: the inability to put new information into explicit memory; no new semantic memories are formed.

Retrograde amnesia: involves memory loss for a segment of the past, usually around the time of an accident, such as a blow to the head.

The cerebellum is involved in implicit memory of skills, and studies involving patients with Parkinson’s disease have indicated involvement of basal ganglia in implicit memory too.

Retrieving Memories

Retrieval: is the process of getting information out of memory storage.

Multiple-choice questions require recognition, identification of learned items when they are presented.

Fill-in and essay questions require recall, retrieval of previously learned information.

Often the information we try to remember has missing pieces, which results in reconstruction, retrieval of memories that can be distorted by adding, dropping, or changing details to fit a schema.

Hermann Ebbinghaus: experimentally investigated the properties of human memory using lists of meaningless syllables.

He drew a learning curve.

He drew a forgetting curve that declined rapidly before slowing.

Savings method: the amount of repetitions required to relearn the list compared to the amount of repetitions it took to learn the list originally.

Overlearning effect: Ebbinghaus also found that if he continued to practice a list after memorizing it well, the information was more resistant to forgetting.

Serial position effect: When we try to retrieve a long list of words, we usually recall the last words and the first words best, forgetting the words in the middle.

Primacy effect: refers to better recall of the first items, thought to result from greater rehearsal

Recency effect: refers to better recall of the last items.

Retrieval cues: can be other words or phrases in a specific hierarchy or semantic network, context, and mood or emotions.

Priming: is activating specific associations in memory either consciously or unconsciously.

Distributed practice: spreading out the memorization of information or the learning of skills over several sessions, facilitates remembering.

Massed practice: cramming the memorization of information or the learning of skills into one session.

Mnemonic devices: or memory tricks when encoding information, these devices will help us retrieve concepts.

Method of loci: uses association of words on a list with visualization of places on a familiar path.

Peg word mnemonic: requires us to first memorize a scheme.

Context-dependent memory: Our recall is often better when we try to recall information in the same physical setting in which we encoded it, possibly because along with the information, the environment is part of the memory trace

Mood congruence: aids retrieval.

State-dependent: things we learn in one internal state are more easily recalled when in the same state again.

Forgetting: may result from failure to encode information, decay of stored memories, or an inability to access information from LTM.

Relearning: is a measure of retention of memory that assesses the time saved compared to learning the first time when learning information again.

Cues and Interference

Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon: Sometimes we know that we know something but can’t pull it out of memory.

Interference: Learning some items may prevent retrieving others, especially when the items are similar.

Proactive interference: occurs when something we learned earlier disrupts recall of something we experience later.

Retroactive interference: is the disruptive effect of new learning on the recall of old information.

Sigmund Freud: believed that repression (unconscious forgetting) of painful memories occurs as a defense mechanism to protect our self-concepts and minimize anxiety.

Misinformation effect: occurs when we incorporate misleading information into our memory of an event.

Misattribution error: Forgetting what really happened, or distortion of information at retrieval, can result when we confuse the source of information—putting words in someone else’s mouth—or remember something we see in the movies or on the Internet as actually having happened.

Language: is a flexible system of spoken, written, or signed symbols that enables us to communicate our thoughts and feelings.

Building Blocks: Phonemes and Morphemes

Language is made up of basic sound units called phonemes.

Morphemes: are the smallest meaningful units of speech, such as simple words, prefixes, and suffixes.

Combination Rules

Each language has a system of rules that determines how sounds and words can be combined and used to communicate meaning, called grammar.

The set of rules that regulate the order in which words can be combined into grammatically sensible sentences in a language is called syntax.

The set of rules that enables us to derive meaning from morphemes, words, and sentences is semantics.

Language Acquisition Stages

Babbling is the production of phonemes, not limited to the phonemes to which the baby is exposed.

Holophrase: one word—to convey meaning.

Telegraphic speech: they begin to put together two-word sentences.

Overgeneralization: or overregularization in which children apply grammatical rules without making appropriate exceptions.

Theories of Language Acquisition

Noam Chomsky says that our brains are prewired for a universal grammar of nouns, verbs, subjects, objects, negations, and questions.

He compares our language acquisition capacity to a “language acquisition device,” in which grammar switches are turned on as children are exposed to their language.

Thinking

Linguist Benjamin Whorf proposed a radical hypothesis that our language guides and determines our thinking.

He thought that different languages cause people to view the world quite differently.

Linguistic relativity hypothesis: has largely been discredited by empirical research.

Metacognition: thinking about how you think

Problem Solving

Algorithm: is a problem-solving strategy that involves a slow, step-by-step procedure that guarantees a solution to many types of problems.

Insight: is a sudden and often novel realization of the solution to a problem.

Trial-and-error approach: This approach involves trying possible solutions and discarding those that do not work.

Inductive reasoning: involves reasoning from the specific to the general, forming concepts about all members of a category based on some members, which is often correct but may be wrong if the members we have chosen do not fairly represent all of the members.

Deductive reasoning: involves reasoning from the general to the specific.

Obstacles to Problem Solving

Fixation: is an inability to look at a problem from a fresh perspective, using a prior strategy that may not lead to success.

Functional fixedness: a failure to use an object in an unusual way.

Amos Tversky and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman studied how and why people make illogical choices.

Availability heuristic: estimating the probability of certain events in terms of how readily they come to mind.

Representative heuristic: a mental shortcut by which a new situation is judged by how well it matches a stereotypical model or a particular prototype.

Framing: refers to the way a problem is posed.

Anchoring effect: is this tendency to be influenced by a suggested reference point, pulling our response toward that point.

Biases

Confirmation bias: is a tendency to search for and use information that supports our preconceptions and ignore information that refutes our ideas.

Belief perseverance: is a tendency to hold onto a belief after the basis for the belief is discredited.

Belief bias: the tendency for our preexisting beliefs to distort logical reasoning, making illogical conclusions seem valid or logical conclusions seem invalid.

Hindsight bias: is a tendency to falsely report, after the event, that we correctly predicted the outcome of the event.

Overconfidence bias: is a tendency to underestimate the extent to which our judgments are erroneous.

Creativity

Creativity: is the ability to think about a problem or idea in new and unusual ways, to come up with unconventional solutions.

Convergent thinkers: use problem-solving strategies directed toward one correct solution to a problem

Divergent thinkers: produce many answers to the same question, characteristic of creativity.

Brainstorm: generating lots of ideas without evaluating them.

Standardization and Norms

Psychometricians: are involved in test development in order to measure some construct or behavior that distinguishes people.

Constructs: are ideas that help summarize a group of related phenomena or objects; they are hypothetical abstractions related to behavior and defined by groups of objects or events.

Standardization: is a two-part test development procedure that first establishes test norms from the test results of the large representative sample that initially took the test and then ensures that the test is both administered and scored uniformly for all test takers.

Norms: are scores established from the test results of the representative sample, which are then used as a standard for assessing the performances of subsequent test takers; more simply, norms are standards used to compare scores of test takers.

Reliability and Validity

If a test is reliable, we should obtain the same score no matter where, when, or how many times we take it (if other variables remain the same).

Several methods are used to determine if a test is reliable.

Test-retest method: the same exam is administered to the same group on two different occasions, and the scores compared.

Split-half method: the score on one half of the test questions is correlated with the score on the other half of the questions to see if they are consistent.

Alternate form method or equivalent form method: two different versions of a test on the same material are given to the same test takers, and the scores are correlated.

Interrater reliability: the extent to which two or more scorers evaluate the responses in the same way.

Validity: is the extent to which an instrument accurately measures or predicts what it is supposed to measure or predict.

Performance, Observational, and Self-Report Tests

Performance test: the test taker knows what he or she should do in response to questions or tasks on the test, and it is assumed that the test taker will do the best he or she can to succeed.