social; week 4; emotion regulation

What are emotions and how are they generate?

emotions are a short-lived complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural, and physiological elements, by which an individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event

Emotion generation: the modal model of emotion

situation → attention → appraisal → response

Situation can be real or imagined

Attention is direct towards the emotional situation

Appraised (evaluated/interpreted) either consciously or unconsciously in terms of what it means in relation to an individual’s goals

Generates an emotional response which leads to changes in experiential, behavioural and physiological response systems

Emotions in daily life

Trampe et al., (2015):

Conducted an experience sampling study (N = 11,000+)

Aimed to capture emotions in everyday life

Found that participants experienced at least one emotion 90% of the time

Positive emotions experience 2.5 times more frequently than negative emotions

Also frequently experience mixed emotions

Most frequently experienced emotions: (1) joy, (2) love, (3) anxiety

functions of emotions

prepare the body for action

influence our thought process

motivate future behaviours

influence interpersonal relationships

However we don’t always let our emotions flow freely

What is emotion regulation?

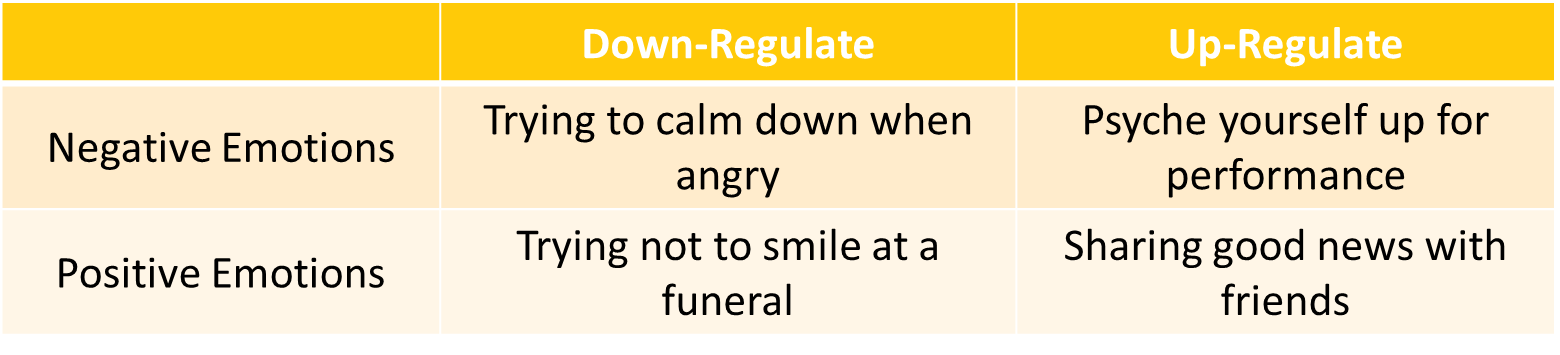

Emotion regulation refers to the processes aimed at influencing which emotions someone has, when they have them and how they experience and express them (Gross, 1998)

Involves monitoring, evaluating and modifying different aspects of emotions, such as the initiation, duration, magnitude, and frequency (McRae, 2013; Thompson, 1994)

Features of emotion regulation

People may also want to maintain their current emotional state

It is a motivated process (Tamir, 2020)

Can be effortful and occur explicitly or it can be automatic and occur implicitly (Gyurak et al., 2011)

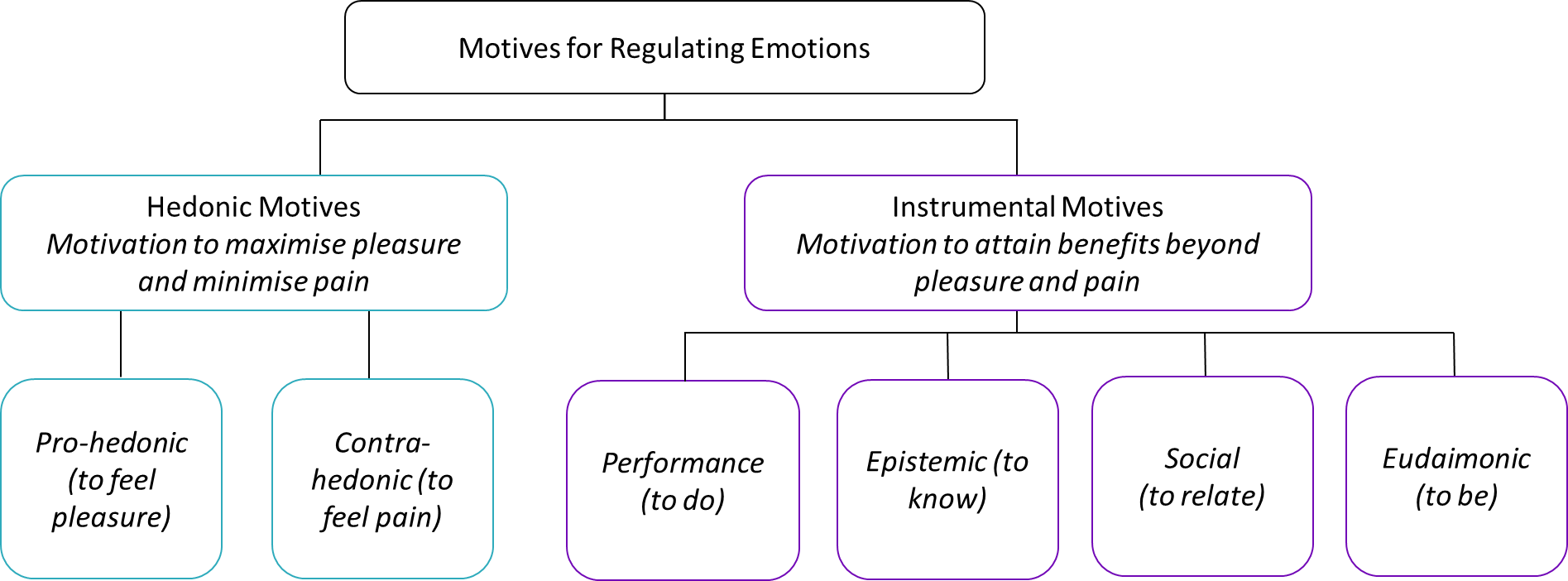

Taxonomy of motives

Hedonic motives- motivations to feel pleasure

people may want to feel pleasant emotions and avoid unpleasant ones

Helps to understand:

down-regulation of negative emotions

up-regulation of positive emotions

Evidence for hedonic motives

People more frequently report attempting to increase pleasant emotions and decreasing negative emotions (e.g., Gross et al., 2006; Riediger et al., 2009)

When asked to list what they want to feel and why, participants listed prohedonic motives (i.e., increase positive or decrease negative) on 50% of the cases (Augustine et al., 2010)

instrumental motives- motivations to perform certain behaviours to achieve certain goals

people may also want to experience emotions that are helpful and avoid unhelpful ones

Helps us to understand:

Up-regulation of negative emotions

Down-regulation of positive emotions

Evidence for instrumental motives

Tamir et al (2008)- performance motives

What did they do?

Participants (N =82) read 2 different game scenarios: confrontational and non-confrontational

Rated preferences for different types of activities before playing

the games: anger-inducing vs. neutral vs. exciting

What did they find?

Participants preferred anger-inducing activities when anticipating

playing a confrontational, but not a non-confrontational game

What does this mean?

People do not always want to feel good, sometimes they want to

feel bad if it will help them to achieve their goals

Lane et al (2011)- performance motives - real life example

What did they do?

Examined runners (N = 360) beliefs about the emotions

associated with ideal performance and the regulatory strategies they used

What did they find?

Greater use of strategies to increase unpleasant emotions was associated with the belief that increasing anger or anxiety helps performance

What does this mean?

Tamir’s findings regarding instrumental reasons for regulating can be applied outside of the lab to help achieve goals

Instrumental motives in daily life

Kalokerinos et al., (2017)

Daily diary study that lasted for 7 days

Reported the most negative event of the day and their instrumental motives in that event

Performance motives were endorsed in approximately 1 in 3 events

Other instrumental motives endorsed in approximately 1 in 10 events

Motives varied depending on the context

Daily diary studies are similar to experience sampling methodologies (ESM) in that data is collected in a naturalistic setting – however, unlike ESM, data will only be collected at one time point (usually towards the end of the day).

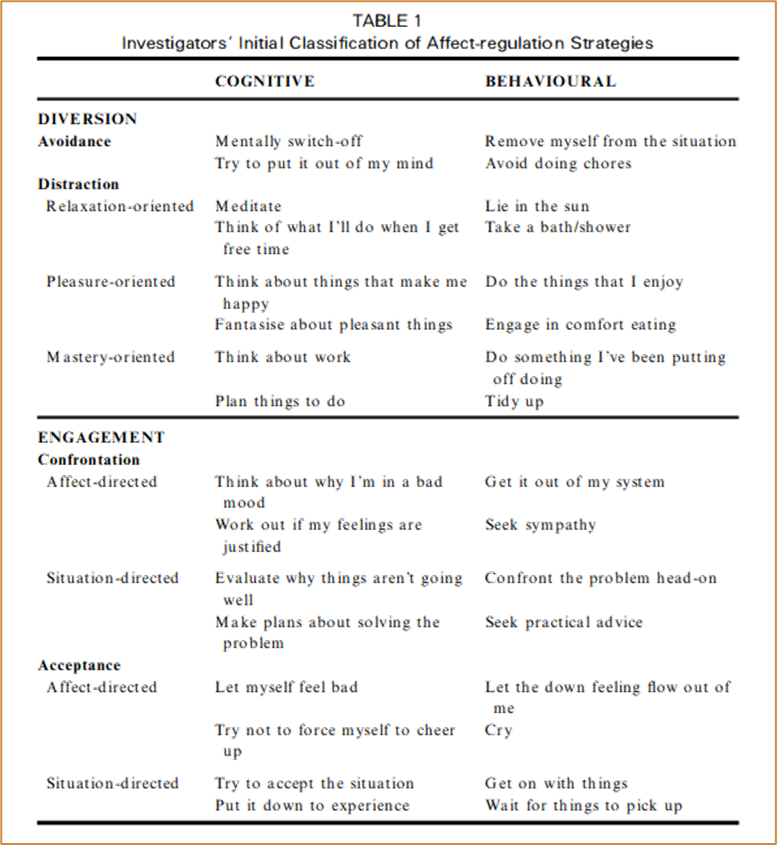

How do people regulate emotions?

Emotion regulation strategies- Parkinson & Totterdell (1999)

Identified 162 distinct strategies*

Organised them based on several features:

Whether they were implemented behaviourally (e.g., doing something) or cognitively (e.g., think about something)

Whether they involved engaging with (e.g., reappraisal) or disengaging from (e.g., distraction) the emotional situation

However, many strategies involve a mixture of both cognition and emotion (e.g., guided mindfulness)

Some strategies can be implemented cognitively or behaviourally

Common Strategies:

Reappraisal: “Modifying how we appraise the situation we are in to alter its emotional significance, either by changing how we think about the situation or our capacity to manage the demands it poses”

Distraction: “Focuses attention on different aspects of the situation or moves attention away from the situation altogether”

Suppression: “When one tries to inhibit ongoing negative or positive emotion-expressive behaviour”

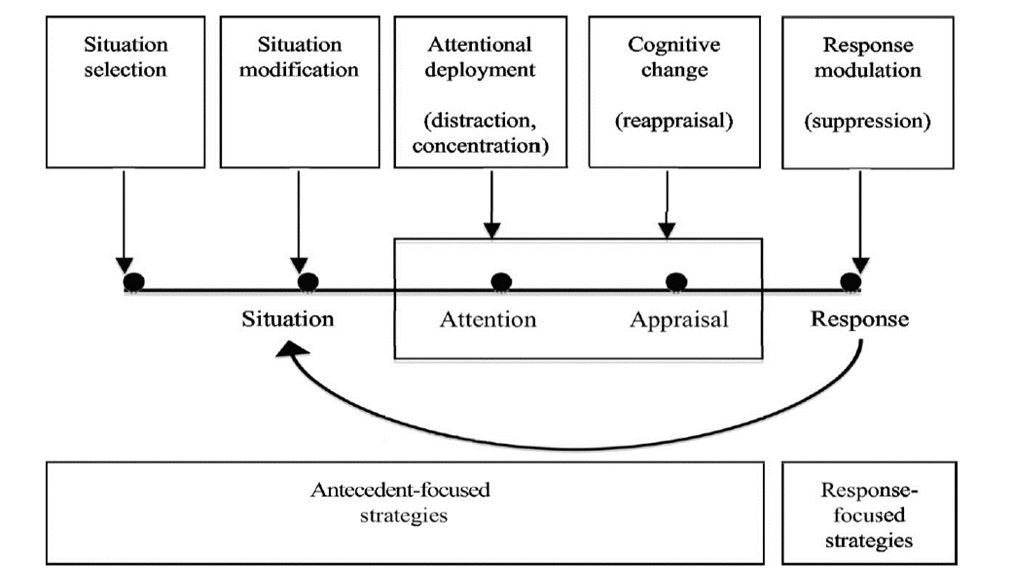

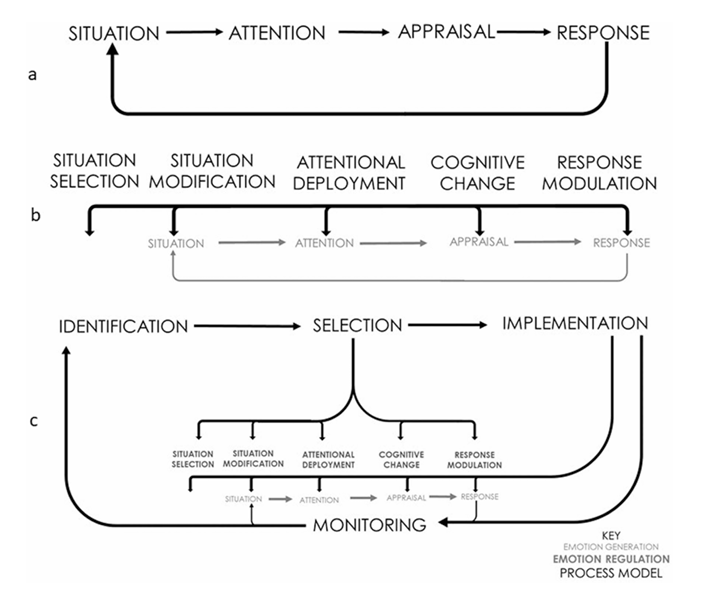

Process Model of Emotion Regulation

Can use different strategies to regulate emotions depending on the point in the emotion generation process the regulation takes place (Gross, 1998)

Strategies before the emotion response = antecedent-focused strategies

Strategies after the emotion response = response-focused strategies

Situation selection

Choose to enter or avoid situations depending on how they will make you feel

Used before the emotion generation process begins

For example, you know attending a particular event will make you feel anxious, so you choose not to go

Situation Modification

Change aspects of the situation you are in

Used during the “situation” stage of emotion generation

For example, you have attended an event and begin to feel anxious, so you limit the amount of time that you spend there

Attentional Deployment

Change what you are focusing on in a particular situation

Used during the “attention” stage of emotion generation

One strategy is “distraction” – for example, you may scroll through social media to take your mind of what is happening in a situation

Cognitive Change

Think about the situation differently

Used during the “appraisal” stage of emotion generation

One strategy is “reappraisal” – for example, you may try to find a “silver lining” in the situation that you are in

Response modulation

Response-focused strategies alter the emotion when it is in full swing

These are used during the “response” stage of emotion generation

For example, you may try to take some deep breaths or try to suppress/hide your true emotional response

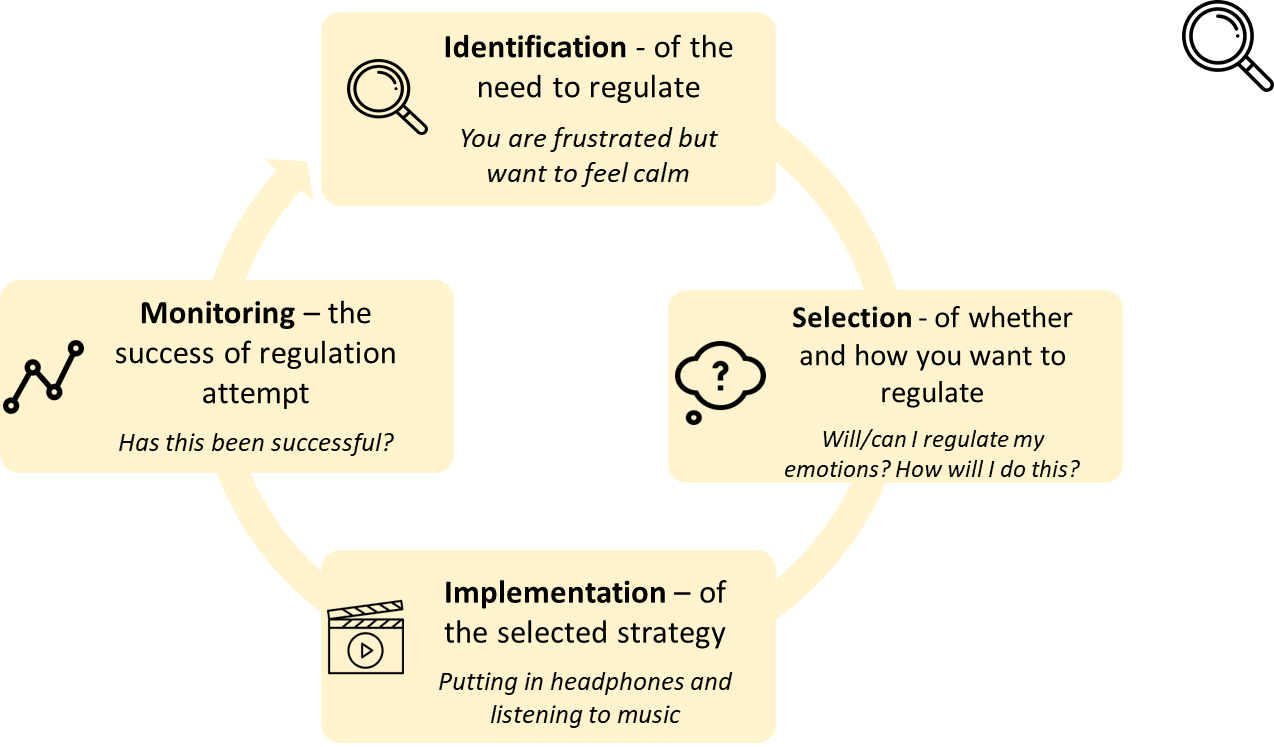

Multi-stage process

Identification- Involves identifying a discrepancy between how you do feel and how you want to feel

selection- Decide whether you want and/or able to regulate your emotions? If so, how will you choose to do this?

implementation- The selected strategy is put into action in an attempt to regulate emotions

monitoring- Involves monitoring the progress and success of the regulation attempt, if successful it can be stopped, if unsuccessful it can be switched

Which strategies are effective?

Webb et al., 2012

Systematic review of 306 studies that asked participants to use a strategy to regulate emotions and then examined the effectiveness

e.g., Donaldson & Lam (2004): compared effects of playing scrabble (distraction) vs., thinking about what feelings mean (rumination) on mood

Studied effects on three different types of outcome:

Experiential, behavioural, physiological

They found:

distraction helped people to feel better, but did not influence behavioural or physiological measures

Concentration exacerbated the emotion (i.e., made them feel worse)

Reappraisal had a small-to-medium sized effects on emotional responses

Suppression influenced behavioural measures but it did not influence how people actually felt and had a negative impact on physiological measures

What does this all mean?

Different emotion regulatory processes are differentially effective

Findings suggest that reappraisal is an effective strategy

The role of context

The effects of different strategies are context specific

Global conclusions regarding one strategy being “better” than another are possibly misleading (Gross, 2014)

Shift in research to consider ER to be an interaction between person, situation, and strategy (Dore et al., 2016)

Suggests that for effective and successful regulation we need to take the context into account and to be able to flexibly switch between different strategies depending on the context (Troy et al., 2016)

Rotweiller et al (2018)

What did they do?

Experience sampling study (N = 68) where participants reported mood, their most intensely experienced emotion and whether it was regarding an exam-related or non-exam-related context

What did they find?

Suppression improved mood in exam-related anxiety and distraction improved mood in only non-exam-related anxiety

What does this mean?

Important to not classify strategies as effective vs. ineffective but also consider the context

Emotion regulation choice- selection of whether and how to regulate (MSP)

Whether and how people choose to regulate their emotions from the strategies available to them in a situation where regulation is warranted

(e.g., Sheppes et al., 2011, 2014)

Intensity of the emotion

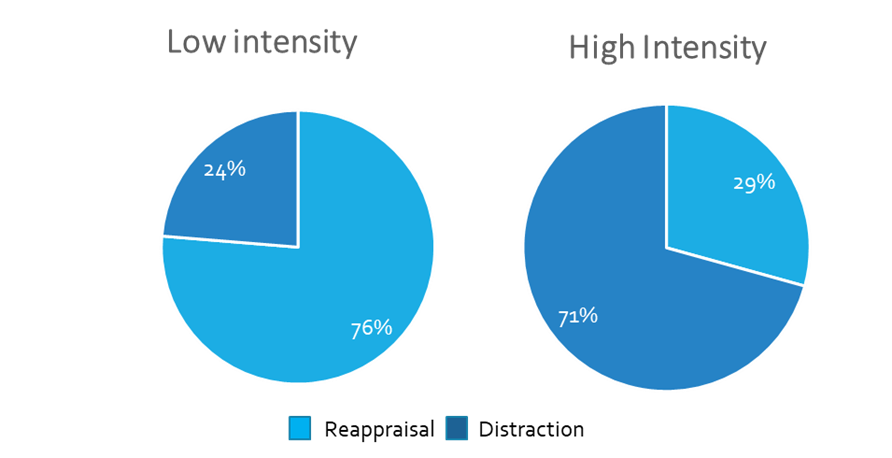

Sheppes et al., (2011)

What did they do?

Participants choose between reappraisal and distraction to regulate emotions in response to images of low vs. high intensity

What did they find?

Low intensity, prefer to reappraise

High intensity, prefer to distract

What does this mean?

Aspects relating to the emotion being regulated influence choice of regulation strategy

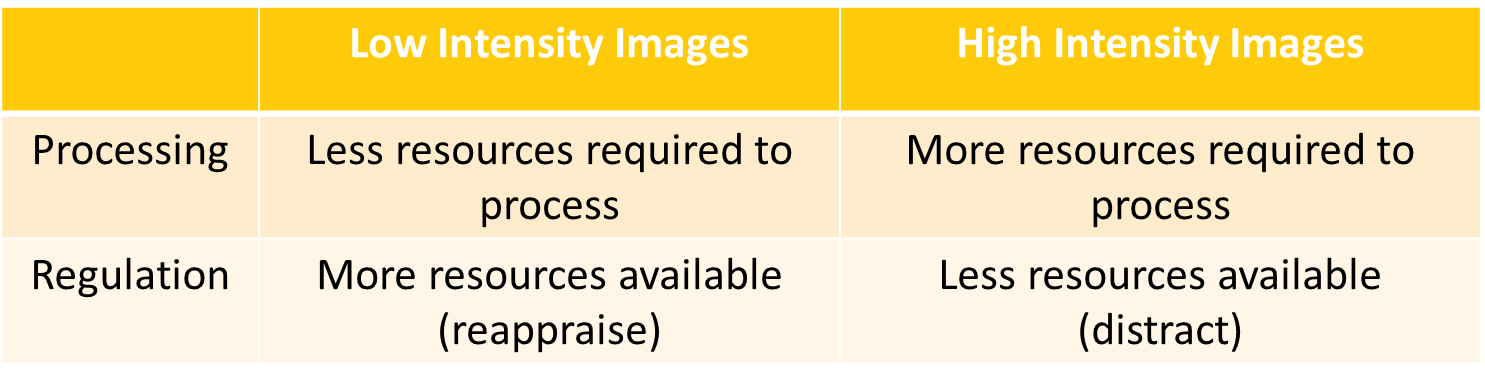

Proposed explanation- sheppes et al., (2011)

Balancing processing the emotion and regulation the emotion

Reappraisal is more effortful than distraction as you have to engage with the emotional stimuli

Why is ERC research important?

Flexibly choosing between different strategies is thought to be associated with psychological health and wellbeing (e.g., Bonanno & Burton, 2013; Troy et al., 2016)

Rigid choice might be associated with various forms of psychopathology (Sheppes et al., 2014)

By understanding what strategies healthy adults make in different situations, deviations can be identified to understand different forms of psychopathology

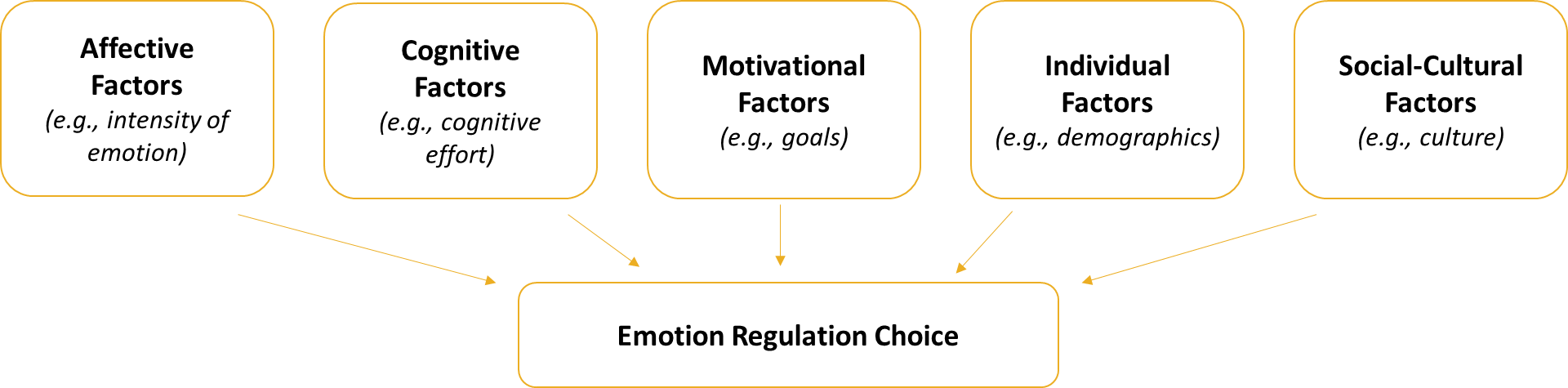

Factors that influence ERC

why is emotion regulation important?

Successful emotion regulation is associated with:

Successful functioning in day-to-day life (Christou-Champi et al., 2015)

Psychological wellbeing and health (Aldao et al., 2010; Martins et al., 2010)

Creating and maintaining social relationships (Gross & John, 2003)

Work performance (Diefendorff et al., 2000)

Emotion regulation and mental health- Aldao et al., (2010)

What did they do?

Meta-analysis to examine relationships between 6 strategies (acceptance, avoidance, problem solving, reappraisal, rumination and suppression) and symptoms of 4 psychopathologies (anxiety, depression, eating, substance-related disorders)

What did they find?

Maladaptive strategies (rumination, avoidance, suppression) were associated with more psychopathology

Adaptive strategies (acceptance, reappraisal and problem solving) were associated with less psychopathology

Rumination showed the largest effect size

What does this mean?

How people regulate their emotions may have an influence on their mental health

What about the social side of emotion regulation?

Interpersonal emotion regulation (IER)

Humans are social beings, and both the experience and regulation of emotions often occur within social contexts (e.g., Zaki & Williams, 2013)

Interpersonal emotion regulation involves the pursuit of an emotion regulation goal in the context of social interaction (Springstein et al., 2024; Zaki & Williams, 2013)

Intrinsic Interpersonal Emotion Regulation- Individual initiates social contact to regulate their own emotions

Extrinsic Interpersonal Emotion Regulation- A person attempts to regulate another person’s emotions

Interpersonal emotion regulation (IER)

Zaki & Williams (2013) also distinguish between response-dependent and response-independent IER

Response-dependent regulation depends on the feedback of another person

Response-independent regulation does not require feedback of the other person

IER in daily life- Tran et al., (2023)

Daily diary and experience sampling methods to explore interpersonal emotion regulation (both intrinsic and extrinsic) in everyday social interactions

Regulate others’ emotions nearly twice a day (extrinsic)

Regulate their own emotions through others around once a day (intrinsic)

Regulate own and others’ emotions in the same interaction approximately every other day

Typically, people were trying to improve how the other person was feeling

Intrinsic IER

Strategies:

Social sharing: When feelings about events are shared with others (covered at L1)

Co-reappraisal: When someone else is sought out to offer a different perspective on an emotional event

People share negative emotional experiences roughly every other day (Liu et al., 2021)

People distribute their emotion regulation needs across different relationships and have a range of “emotionships” (Cheung et al., 2015)

Extrinsic IER

four key characteristics:

1.Goal-directed

2.Deliberate process

3.Targets an affective (i.e., feeling) state

4.Belongs to someone else than the person doing the regulating (i.e., has a social target)

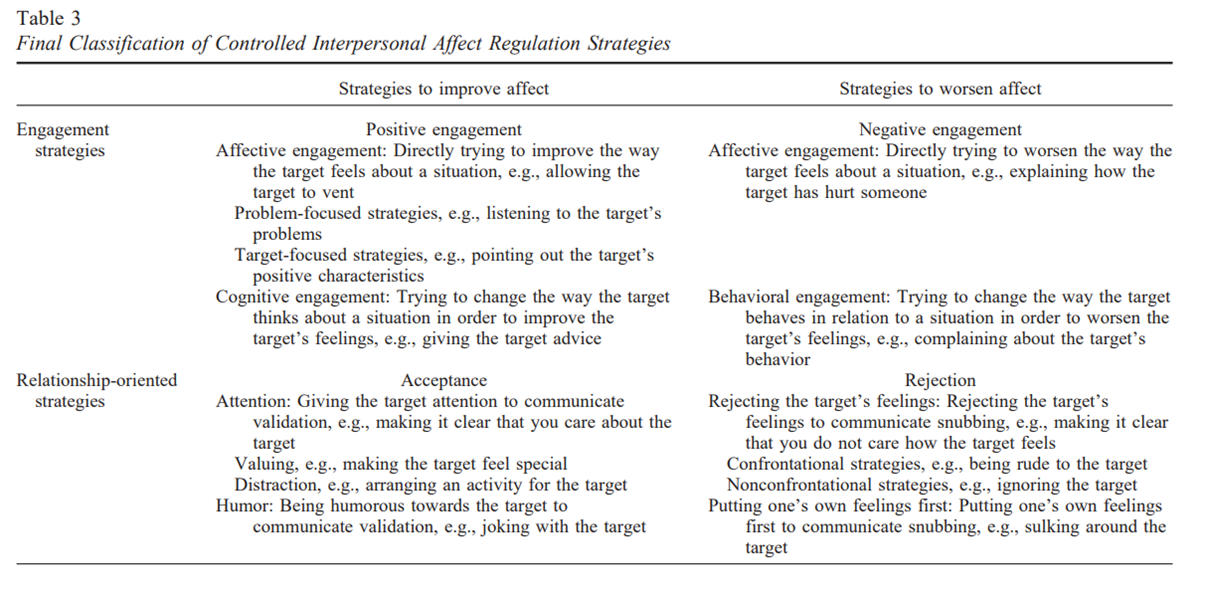

Extrinsic IER: stratgeies- Niven et al., (2009)

Questionnaires, diary studies and a card sorting task

Key distinctions:

Improve vs. worsen affect

Engagement vs. relationship- oriented strategies

Extrinsic IER in daily life- Double et al., (2024)

What did they do?

Used experience sampling to look at the extrinsic IER strategies people use and how they relate to personal characteristics (N = 165)

Assessed use of 5 strategies: humour, distraction, cognitive reframing, receptive listening and valuing

Measured empathy, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, and personality (Big-5: conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, openness)

What did they find?

People do frequently report regulating other people’s emotions

Regulate emotions of people we are close to (e.g., partner, friends)

Receptive listening and valuing were used most frequently (humour and distraction used least frequently)

Personality traits, empathy, and gender influenced strategy use

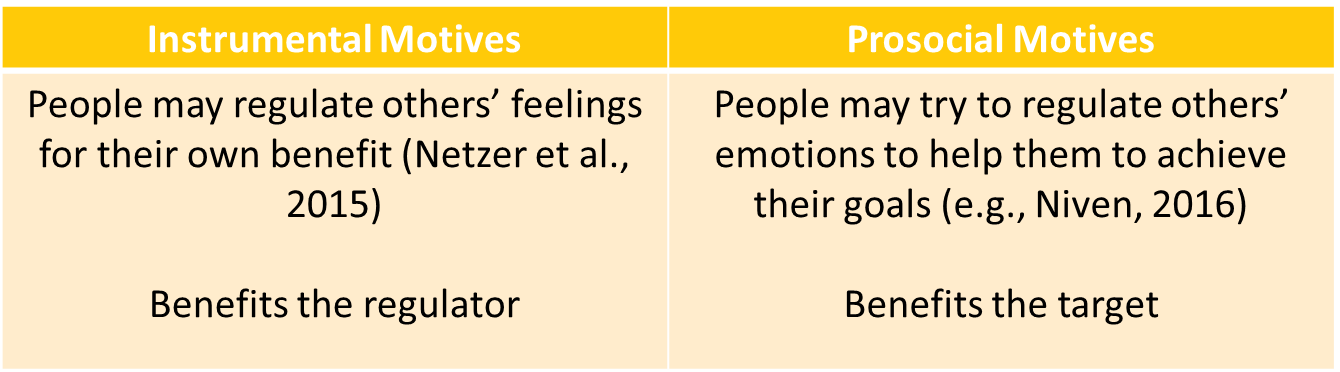

Extrinsic IER: Motives

People do regulate others emotions for hedonic reasons (e.g., Gable & Reis, 2010; Rime, 2007)

People will also make other people feel worse to achieve certain goals (e.g., Lopez-Perez et al., 2017; Netzer et al., 2015; Niven et al., 2016)

Instrumental and prosocial motives- Niven et al., (2016)

what did they do?

Created situations in which it would be useful for participants to be either happy (collaborative game) or angry (aggressive game)

Participants were asked to select stimuli for a friend facing these situations (i.e., what to view before playing a collaborative or angry game)

Half of the participants were in a situation where they would benefit themselves (instrumental) and half where the other participant would benefit (prosocial)

What did they find?

When enhancing friends' performance would benefit their friend (prosocial) or themselves (instrumental), participants selected performance-conducive emotion-inducive stimuli

Either happy (collaborative game) or angry (aggressive game) stimuli

What does this mean?

People will induce emotions that they think will be useful to achieve a goal, even if this means making someone feel more negative

Interpersonal motives in daily life- Tran et al., (2025)

Two week daily-diary study to examine why people regulate others’ emotions in social interactions

Most commonly used to make others feel better (55% of ER instances)

But people did often have self-focused motives too

Wanting to feel helpful or good about the self (16%)

To avoid feeling uncomfortable (12%)

People also regulate others to help them achieve a goal (19%) or to achieve their own goals (17%)

IER outcomes

Development of closer friendships (e.g., Rose et al., 2007)

Increased feelings of intimacy between romantic partners (e.g., Horn et al., 2019)

Increased feelings of social connections and more supportive relationships (e.g., Williams et al., 2018)

More diverse “emotionships” associated with higher wellbeing (e.g., Cheung et al., 2015)

There are benefits for both the regulator and target for extrinsic IER

Effectiveness of intrapersonal vs interpersonal emotion regulation- Levy-Gigi & Shamay-Tsoory (2017)- What did they do?

Randomly assigned each person in a couple (N = 47) as the target or the regulator

The target viewed pictures and was instructed to either:

Choose and apply a strategy to regulate their own emotions (intrapersonal)

Apply a strategy chosen by their partner (extrinsic interpersonal)

What did they find?

Extrinsic interpersonal emotion regulation was

more effective at reducing distress than

intrapersonal

What does this mean?

Highlights the advantage of an outside

perspective in reducing stress and improving

emotion regulation

Summary

Emotion regulation refers to how people shape their own and other people’s emotions

People regulate emotions for a range of reasons: prohedonic motives and instrumental motives

There are a range of strategies available to people to regulate emotions, but the effectiveness of the strategies depends on the context

People can choose how to regulate emotions and there are a range of factors that influence this choice: affective, cognitive, motivational, individual and socio-cultural

Emotion regulation isn’t confined to intrapersonal processes, people often engage in emotion regulation in social contexts either to regulate their own emotions (intrinsic IER) or to help others to regulate their emotions (extrinsic IER)

There are a number of personal and social outcomes associated with successful regulation

Reading

Emotion, 1-9

emotion, 803-810

emotion regulation

refers to attempts to influence emotions in ourselves or others

in the 1990s, the field of emotion regulation (ER) began to emerge as a distinct research domain

ER focuses on people’s attempts to influence emotions, defined as time-limited, situationally bound, and valenced (positive or negative) states

Compared with historical predecessors, ER is broader in that it is not limited to the down-regulation of negative emotions (fear, anxiety, stress) but encompasses up- and down regulation of positive and negative emotions in accordance with regulation-related goals.

Whereas goal pursuit (and therefore ER) is often conscious and deliberate, it can also occur implicitly, outside conscious awareness

the process model of ER

framework that has helped to organize work on ER

distinguishes 5 families of strategies defined by when they impact the emotion generation process.

embeds these ER strategies in stages in which a need for regulation is identified, a strategy is selected and implemented, and monitoring occurs to track success.

At the first level of this model, emotion generation is sequentially described as encountering relevant situations, at tending to key aspects of those situations, appraising the situations in relation to active goals, and having experiential, physiological, and/or behavioural responses. For example, an individual might have a job interview (situation), notice the cool demeanor of the evaluator (attention), interpret the coolness as displeasure with the interviewee (appraisal), and experience fear, shortness of breath, and begin fidgeting (response) in the interview.

The output of the emotion generation cycle creates a new aspect of the situation (the situation is now sitting in a job interview while feeling afraid, being short of breath, and fidgeting), and the cycle repeats.

According to the process model, the ER cycle begins with a discrepancy between someone’s goal state (i.e., the emotional state they desire) and the actual (or projected) state.

This discrepancy is then identified as an opportunity for regulation (1), a regulation strategy is selected from alternatives (2), the strategy is implemented through specific tactics (3), and the whole cycle is monitored for success in achieving the regulatory goal.

In the job interview scenario, identification would involve noticing the feeling of fear but wanting to feel excited, paired with believing it is possible for this emotion to change. Selection would occur when deciding to modify expressive behaviour rather than attention to the interviewer. Implementation would involve increasing tension on facial muscles to prevent displaying a worried countenance. Monitoring could include asking, “Am I feeling more excited because I decided to not display my worry?” as well as noting changes in the environment, which would indicate the need to continue, stop, or switch to a different ER strategy—processes that con tribute to ER flexibility

Reappraisal

Much of the research to date has focused on a strategy called cognitive reappraisal

involves changing how one thinks about a situation to influence one’s emotional response.

Reappraisal is thought to be generally effective and adaptive, but there are important qualifications.

extrinsic regulation

the regulation of someone else’s emotions

What kinds of things do people do when they want to influence emotion?

ER strategies can be organized into five families according to the emotion generation stage at which they first intervene

what consequences does emotion regulation have?

Most studies of ER either manipulated ER or assessed typical patterns of ER use.

The consequences of manipulating ER (implementation stage) have typically been the purview of basic affective science because strategies are trained and cued in the laboratory, and the measured emotional outcomes are temporally proximal to the regulation.

Researchers often refer to this as ER effectiveness, ability, capacity, or success.

Initial studies of ER success tested the hypothesis that the timing of the ER strategy (either relative timing within one cycle or timing of earlier Vslater repeating cycles) predicted ER success.

By contrast, patterns of ER use (selection stage) have largely been studied within personality, developmental, and clinical psychology, are often measured using questionnaires, and many consequences are relatively distal associates.

Typical ER use is referred to as ER tendency, ER use, habitual ER, trait ER, or ER frequency. ER frequency has increasingly been operationalized as how often someone chooses to use a particular strategy in the lab.

Reappraisal is frequently successful, as it often results in the desired changes in self-reported emotion, peripheral physiology, and neural measures of emotion.

Studies using experience sampling to examine reappraisal in more natural environments have been largely consistent with laboratory findings.

Reappraisal’s success contrasts with suppression, which results in weak, null, or paradoxical (reversed) changes in negative emotion.

Consequences of reappraisal also contrast which distraction, in that reappraisal results in less short-term success in decreasing negative emotion than distraction, but is more effective upon later encounters with the stimulus.

Greater reappraisal frequency is associated with adaptive outcomes such as greater physical health, higher academic achievement, more positive social outcomes, greater psychological well being, and fewer symptoms psychopathology. This contrasts the greater suppression frequency, which is often associated with lesser well being, more symptoms of psychopathology, and lesser relationship satisfaction. However, suppression seems to be a relatively adaptive skill early in development, and is associated with greater school readiness in preschoolers

What determines (moderates) emotion regulation?

Researchers have identified individual and environmental factors that moderate the ER success or frequency.

Reappraisal’s success varies by context: Laboratory studies indicate that reappraisal is more successful when the negative emotion is of moderate intensity, is generated from cognitive rather than perceptual emotional stimuli, and when there is relatively more time available to regulate.

The presence of positive emotion, perhaps only when related to the negative emotion-eliciting situation, may facilitate reappraisal success.

The engagement of prefrontal cortex (PFC) control regions during reappraisal suggests that reappraisal may be less successful under conditions that impair PFC-dependent cognition. Indeed, sleep deprivation, poor-quality sleep, stress, and developmental variation in PFC integrity and functioning are associated with less successful reappraisal.

What factors determine how often people use reappraisal?

Reappraisal frequency is less heritable and more open to nonfamilial environmental influences than emotion-relevant personality dimensions or suppression frequency.

Contextual and individual factors that determine ER frequency include social relationship partners, especially in childhood, and personality factors.

Individuals select reappraisal more frequently when the stimuli to be regulated are of lesser intensity or contain more reappraisal affordances and use reappraisal less frequently when they have anticipatory information about the content (but not timing) of emotion-relevant events.

When stimuli are of high intensity, distraction or suppression are more likely to be used. Individuals from cultures that value self-reflection and insight tend to use reappraisal more frequently than average, whereas individuals from cultures that value open expression of emotion tend to use suppression less frequently.

Furthermore, there is evidence that a history of having short-term success might lead to more frequent use of maladaptive strategies such as self-injurious behaviour

What are the mechanisms (mediators) of emotion regulation?

Neurobiological mechanisms of reappraisal implementation include brain systems that support cognitive control and linguistic elaboration, compared with distraction, which uses more external attentional control systems, and suppression, which uses more inhibitory systems.

Engagement of reappraisal-related prefrontal and parietal cognitive control and linguistic elaboration systems can lead to either diminished or enhanced emotional responding, in correspondence with one’s emotional goal.

Clarifying how reappraisal relates to affective versus cognitive control may clarify the developmental trajectory of ER during adolescence.

Likewise, clarifying whether reappraisal can be driven by proactive versus reactive control processes may help us determine the most effective and adaptive ER strategies to use in adulthood and later in life.

Another potential mechanism is the (up-)regulation of positive emotion, which may help us better understand associations between ER and psychopathology.

Psychological mechanisms governing the selection of reappraisal include decision-making processes, in which the need for regulation is balanced with anticipated success, the estimated cognitive costs of implementing candidate strategies, and the desire to engage with the emotional aspects of the situation to be regulated.

The process of reappraisal selection may engage a similar frontoparietal network to that engaged during reappraisal implementation, but few studies are able to separate mechanisms of selection from implementation

Which interventions improve emotion regulation?

Interventions can target neurobiological or psychological mechanisms of ER and measure their proximal or distal effects.

Interventions for children often educate parents and/or teachers about healthy ER and offer for children to observe and practice ER either through parent socialization at home or instruction about emotional intelligence at school.

Less frequent, largely adaptive strategies like reappraisal and overuse of maladaptive strategies like rumination and suppression characterize clinical groups with mood disorders.

The goal is to decrease the frequency with which maladaptive ER strategies are used and to increase the frequency and success with which adaptive ER strategies are used.

Cognitive therapies, like CBT, directly target reappraisal skills.

CBT improves self-reported reappraisal success, and other interventions that improve reappraisal success include direct reappraisal training using a picture based task.

Neurobiological interventions like antidepressant medication increase reappraisal frequency and success, and noninvasive stimulation of neural regions engaged during reappraisal increases reappraisal success and decreases symptoms of depression.

direction for future research

What about the consequences, determinants, mechanisms, and interventions that influence the identification and monitoring stages?

The consequence of not identifying a need to regulate is emotion regulation failure, and identification appears to be jointly determined by an individ ual’s emotion goals and their belief in the malleability of emotion. Mechanisms of identification include processes that govern goal pursuit, including goal setting, goal striving, or the use of implementation intentions.

Interventions for identification target the valuation of specific emotional states or beliefs about emotion malleability. Although monitoring is an important stage of the process model, few studies have examined consequences, deter minants, mechanisms, and interventions related to monitoring of ER specifically. One exciting exception is the successful externalization of monitoring in functional magnetic resonance imaging–based neurofeedback.

In future research on emotion regulation, it will be important to examine the full range of stages in the emotion regulation process. We have distinguished between how well and how often people use reappraisal. Why is this important?

In many circumstances, they are conflated, especially as researchers, including ourselves, briefly summarize findings of previous studies of ER. This conflation is reasonable because the short-term success of reappraisal (e.g., successfully reduced negative emotion) could logically lead to some of the long-term adaptive associates of reappraisal frequency. (e.g., lower levels of daily negative affect). However, there is reason to believe how well and how often reappraisal is used might be distinct constructs, which is especially apparent in clinical contexts.

One of the most reliable findings in the ER literature is that greater use of reappraisal is related to fewer symptoms of psycho pathology, but studies of how well reappraisal is used by clinical groups have reported weak or null differences from non clinical groups. With few exceptions, it appears that members of clinical groups can successfully use reappraisal in a laboratory setting.

Meta analyses indicate that members of clinical groups demonstrate reappraisal success that is indistinguishable from controls in 80% of published studies. What is the source of this disconnect between reappraisal success and use?

One possibility is that although individuals from clinical groups can use reappraisal successfully when cued, they fail to appropriately identify moments at which ER would be helpful in everyday life. Alternatively, members of clinical groups may in fact be able to identify moments at which ER would be helpful but for one reason or another choose not to use reappraisal very frequently in everyday life. It is also possible that laboratory use measures capacity, which is an over estimate of actual success everyday life.

Finally, it is possible that this disconnect between reappraisal use and success is an artifact of the way these constructs are measured (cumulative emotion ratings on a laboratory task vs. self-report responses). The source of the disconnect could have important implications for ER intervention science, which would respectively focus on using remind ers and encouragement to select and initiate reappraisal in every day life, improving conditions for implementing reappraisal in everyday life, or developing, refining, or combining measures of reappraisal that most closely correspond to documented emotional difficulties in clinical groups.

Our goal is to show that research on ER has produced sharpened definitions and generative models of ER, outlined different emotional consequences of engaging in different types of ER, identified moderating contextual and individual factors that impact ER, described psychological and neurobiological mechanisms by which regulation influences emotion, and documented the effect of ER interventions on short- and long- term outcomes. Additional reading beyond the scope of our discussion can be found in online supplemental materials. In our view, when considering (or conducting) research on ER, it is helpful to clarify which stage of the ER process (identification, selection, implementation, or monitoring) is being described, manipulated, or measured because this will help to make subsequent ER interventions more targeted and precise. Whereas we have focused primarily on cognitive reappraisal here, research on other ER strategies is obviously critical to clarify the most adaptive and effective ways to influence emotions, with the ultimate goal of finding better ways to achieve better emotional lives.

Second reading

A classic intuition: regulation is interpersonal

Emotional experiences often encourage attempts at control. We sit in traffic, worry about our health, argue with our spouses, and in many cases try to improve on the feelings these experiences bring us. Emotion regulation comprises such attempts, through the implementation of implicit or explicit goals to change the trajectory of either positive or negative emotional experiences.

Researchers have catalogued several emotion regulation strategies—such as reappraisal, distraction, expressive suppression, and distancing—through which people modulate their affect. Extant research investigates how individuals deploy these processes in solitude. However, people experiencing affect commonly choose not to go it alone, but instead turn to others for help in understanding and managing their emotions.

Such interpersonal emotion regulation is a central feature of our psychological lives: individuals draw on others’ support as a resource to dampen stress and intensify positive affect, and even benefit from the mere presence of others during difficult times. Complementing such efforts, individuals often attempt to regulate others’ emotions, through empathic, supportive, and prosocial behaviours. Interpersonal processes critically scaffold emotion regulation throughout life. For instance, coregulation—or shared patterns of affective oscillation across individuals—characterize infant–parent interactions in ways that shape the development of attachment.

Early in life, interpersonal regulation may be the rule, not the exception. Here we focus on the less explored phenomenon of interpersonal regulation in adulthood. Scientists have long studied “pieces” of interpersonal emotion regulation, such as social support receipt and provision, social sharing of affective states, and motivations to help others improve their emotional states.

We propose a framework: We begin by mapping a “space” of interpersonal regulatory strategies according to whether an individual uses interpersonal situations to regulate his own or another person’s emotion. We then consider processes that can support interpersonal regulation, differentiating between those that are response-dependent—and rely on an interlocutor’s feedback—or response-independent—and occur in social contexts but do not require a particular response from one’s interaction partner. The resulting framework organizes a raft of phenomena, ranging from emotional expressivity to prosocial behaviour, clarifies the situations under which interpersonal regulation might succeed or fail, and suggests several directions for future work.

Mapping the space of interpersonal regulation

In the past few years, a small but growing number of research programs have made critical progress in exploring various facets of interpersonal regulation, and a number of theorists have produced important and compelling models of interpersonal regulatory processes. Interestingly, across these models, the term inter personal regulation is often used to capture related but distinct phenomena, including individuals’ desire to share their emotional states with others, the attenuation of negative affect in the presence of others, and the motivation to change others’ affective states. Multiple uses of the same term can slow progress in developing systematic models of interpersonal regulation. Here, we attempt to integrate existing work on this domain into a simple, accessible framework through which to consider the broader domain of interpersonal regulation.

In mapping the space of interpersonal regulation, we make four conceptual “cuts”:

(a) specifying when regulation is interpersonal and when it is not;

(b) distinguishing interpersonal regulation from incidental affective consequences of social interaction;

(c) broadly dividing classes of interpersonal regulation based on whether individuals use social interactions to regulate their own or others’ affect;

(d) drawing a boundary between different processes that comprise interpersonal regulation.

Intra- Vs interpersonal regulation

The first task for any model of interpersonal regulation is specifying when a regulatory episode is “interpersonal” and when it is not. This is tricky, because intra- and interpersonal regulation exist on a continuum. For this article, we constrain our definition of interpersonal regulation to episodes

(a) occurring in the context of a live social interaction,

(b) representing the pursuit of a regulatory goal (consistent with the broader definition of regulation).

This is because the rich, multiperson processes that characterize interpersonal regulation—and especially the response dependent processes described below—require such interactions. However, it is important to note that although interpersonal regulation as defined here can only occur in social contexts, individuals can deploy intrapersonal regulatory processes (e.g., reappraisal) both when they are alone and with others.

Interpersonal Regulation Versus Interpersonal Modulation Just as important as mapping the boundaries of “interpersonal” phenomena, our model must clarify when interpersonal episodes constitute “regulation” and when they do not. For instance, Coan et al have compellingly demonstrated that the mere presence of others attenuates negative affect in the face of stressors. This suggests that any social interaction could constitute regulation, consistent with the broader theory of stress buffering. Nonetheless, we feel that a meaningful border can be drawn between such interpersonal modulation of affect and interpersonal regulation. This is because regulation typically refers to the pursuit of a goal to alter one’s affective state, whereas incidental modulation of affect by social presence can occur outside of any such goal. That said, social modulation plays a widespread and critical role in individuals’ affective lives, and can be integrated into a theory of interpersonal regulation. Specifically, individuals who are buffered from stressful events by the presence of others may have exerted a regulatory goal earlier, in choosing to seek out social contact when stressors are eminent.

Schachter (1959) demonstrated just such an effect in his classic studies of affiliation under threat. The desire for social contact in the face of looming negative events is likely evolutionarily old; for instance monkeys and rats seek out social contact under stressful conditions. Thus, we believe that modulation of affect by the mere presence of others is intimately tied to interpersonal regulation, and often represents the result of an earlier regulatory goal to seek out contact in anticipation of stressors. This can be thought of as an interpersonal analogue of Gross’ (1998) “situation selection,” in which individuals seek out contexts that will reduce the need for later regulation

Intrinsic Vs extrinsic interpersonal regulation

We further divide interpersonal regulation according to whether the “target” of a regulation attempt is intrinsic or extrinsic. By intrinsic interpersonal regula tion, we refer to episodes in which an individual initiates social contact in order to regulate his own experience; by extrinsic interpersonal regulation, we refer to episodes in which a person attempts to regulate another person’s emotion. In an example, Alan (Person A) attempts to regulate his own affective state by soliciting contact with Betsy, whereas Betsy (Person B) attempts to regulate Person A’s affect. As such, Person A engages in intrinsic regulation whereas Person B engages in extrinsic regulation

Response-dependent Vs response-independent processes

Finally, we distinguish between two classes of processes that can support either intrinsic or extrinsic interpersonal regulation: response-dependent and response-independent.

Response dependent processes rely on the particular qualities of another person’s feedback. For instance, Person A may feel better after expressing his emotions to Person B, but only if Person B responds supportively.

Response-independent processes occur in the context of social interactions, but do not require another person respond in a particular way. For instance, Person A might produce behaviours—such as labelling his emotions—while interacting with Person B, and these behaviours could regulate his affect regardless of Person B’s response.

It is important to note that response-dependent and response independent processes are orthogonal to extrinsic and intrinsic regulation. That is, in our example, Person A and Person B can engage intrinsic and extrinsic regulatory strategies through both response-dependent and response-independent processes.

These two dimensions (intrinsic vs. extrinsic; response-dependent vs. response-independent) create a 2 2 matrix of interpersonal regulatory processes. Different regulatory classes or processes are NOT mutually exclusive. Similarly, individuals within an interaction often simultaneously engage in intrinsic and extrinsic regulation, fluidly ex changing roles during social encounters, and likely use response-dependent and response-independent regulatory processes in tandem.

Nonetheless, boundaries between interpersonal regulatory types and processes are useful in organizing data and concepts in this domain. For instance, these distinctions allow us to integrate previous models of interpersonal regulation under one simple framework. Person A shares his emotions as a way of recruiting social resources, whereas Person B regulates Person A’s state by providing support. These individuals are clearly deploying different regulatory strategies, and yet both have been referred to as “interpersonal emotion regulation”. Under the current model, we can differentiate Person A and Person B as using intrinsic and extrinsic interpersonal regulation, respectively.

Building a Process Model of Interpersonal Strategies

In the above example, how does Person A benefit from his contact with Person B? And what motivates Person B’s response to Person A?

Independent lines of research suggest a number of very different answers to this question. We now use the space mapped above to organize this prior work and begin building a model of the many potential processes that make up intrinsic and extrinsic interpersonal regulation.

Intrinsic interpersonal regulation

Under our model, Person A’s affective experiences produce a motive to control emotion, and this motive in turn prompts him to seek contact with, and express his emotion to, Person B. A raft of studies supports the prediction that affective experience indeed causes individuals to share their experience with others. In fact, social sharing ranks among the most prevalent responses to emotional events, regardless of whether those events are positive or traumatic, consequential or trivial, and measured retrospectively or induced experimentally. Social sharing need not always represent an attempt to regulate one’s emotion: some forms of social expression—especially facial actions—are often conceptualized as automatic components of affective experiences that occur regardless of any motive. However, at least two features of social sharing suggest that it often does reflect regulatory motives.

First, individuals modulate their expressive behaviour (including facial actions) in response to the presence of audiences.

Second, individuals are most likely to share affect with others whom they believe can, in fact, help them. These data suggest that social sharing—at least in some cases— reflects interpersonal regulatory goals. Such sharing, in turn, can regulate Person A’s affect by response-dependent and/or response independent mechanisms.

Response-dependent processes

Intrinsic interpersonal regulation is risky because its success often depends on more than one person. Consider our example above. If, instead of comforting Person A, Person B had rattled off her high marks in organic chemistry and pointed out that people who perform poorly in that class often fail medical school entrance exams, Person A might feel considerably less well after this encounter. Response-dependency is a common feature of inter personal regulation. For instance, sharing good news with others can intensify positive affect, but only when others respond with enthusiasm, and social sharing can soften the impact of negative experiences, but only when others respond supportively.

How do response-dependent mechanisms facilitate regulation?

At least two possibilities come to mind. First, others’ supportive behaviours can produce a safety signal that allows individuals to reconsider the events that elicited their emotion. In our scheme, Person B’s supportive response makes clear that Person A does not have to face a negative event alone, but instead has access to both Person A and Person B’s shared psychological resources. This resource appraisal can, in turn, transform a stressful event into a less threatening challenge, and alter responses to such events at subjective, physiological, and neural levels. 1 Intrinsic interpersonal regulation can also work through a second, more diffuse response-dependent mechanism. Even without directly supporting Person A, Person B can provide signals that she shares Person A’s experiences. Evidence suggests that such shar ing (i.e., “being on the same page” as someone else) is experienced as rewarding in and of itself. Further, sharing experiences and opinions with others serves as a proximate signal to affiliation: increasing the likelihood of longer-term connections and support between Persons A and B. Affiliation cues fulfill a deep-seated need for interpersonal contact that could modulate Person A’s affect and perception of support availability, even without changing their appraisal of a particular eliciting event. Indeed, this mechanism dovetails nicely with both Rimé’s (2009) description of socioaffective consequences of social sharing and Lakey and Orehek’s (2011) description of affectively consequential discussion not directly related to stressful events.

Response-independent processes

Intrinsic interpersonal regulation can also work through processes that are independent of an audience’s particular response. Even if Person B fails to respond appropriately, Person A’s disclosure itself may contain psychological “ingredients” that promote regulatory success. For instance, to communicate emotions to others, targets must first label their affective states and the sources of those states; doing so often requires refining appraisals of the emotion one is feeling. This socially inspired conceptual sharpening, in turn, can serve a regulatory goal. For instance, labelling affective states—especially in a nuanced, or “fine grained” way— can reduce the ambiguity of affective states and facilitate coping, especially when labelling is accompanied by assessment of the causes underlying an affective state. To the extent that social sharing produces labelling and assessment, it should also facilitate regulation, regardless of Person B’s response.

Extrinsic interpersonal regulation

In the example above, Person A’s expressive behaviour serves as an “input” to Person B’s empathic affective experience (Figure 1b). Empathy comprises multiple distinct, but related phenomena, including understanding a social target’s state and sharing that state. These empathic components are neurally and behaviorally dissociable, but both depend on Person A’s ability to effectively express his affect. Further, both relate to a third empathic subcomponent: the motive to alter the trajectory of Person A’s emotional experience. This motive comprises an extrinsic regulatory goal; Person B can pursue this goal through a number of prosocial behaviours, such as providing Person A with situation-specific emotional support, comforting messages, diffuse support not associated with a single event, or practical support such as providing material resources. Although researchers rarely describe empathy and prosocial behaviour in regulatory terms, doing so offers an opportunity to synthesize several aspects of other-oriented affect and behaviour that are often considered independent or contradictory. Specifically, we can characterize prominent theories of these behaviours as examples of response-dependent and response-independent mechanisms supporting extrinsic regulatory goals.

Response-dependent processes

One dominant psychological model of prosociality holds that generous behaviours represent fundamentally “other-oriented” motivation: On this view, the goal to change another person’s state represents an end unto itself. As such, this goal cannot be fulfilled without succeeding in helping the other person. Under our framework, this motive is consistent with response-dependent regulatory processes. For instance, consider an episode in which Person B attempts to regulate Person A’s emotion. Person B can only fulfill her regulatory goal by receiving feedback from Person A indicating that he indeed has been helped. As delineated by the dotted line in Figure 1b, this is no guarantee, as prosocial support often fails to modulate a target’s affect. Beyond offering evidence that Person B has succeeded in her regulatory goals (helping Person A), feedback from Person A can also improve Person B’s own affective state.

How might this occur?

One possibility is that Person B could vicariously experience the affective consequences of her own prosocial behaviour. That is, just as Person B experiences negative affect via her vicarious sharing of Person A’s initial expressions, Person B could also experience a reduction in negative affect via signs of Person A’s successful regulation. In fact, this response-dependent mechanism likely provides powerful motivation for other-oriented behaviour. Extant work at both behavioural and neural levels of analysis converges to suggest that individuals’ levels of affect sharing predict prosocial behaviour, suggesting that individuals who experience strong vicarious affect use prosocial behaviour in the service of regulation.

response-independent processes

As with intrinsic interpersonal regulation, extrinsic regulatory goals can be fulfilled even in the absence of an interlocutor’s response. This description may at first appear unintuitive: Person B’s goal appears specifically geared toward Person A’s state, making it difficult to imagine that goal being accomplished without input from Person A. However, as described by Tomasello et al. (2005), goals can be divided into two classes: external goals (the state of the world an individual wishes to achieve) and internal goals (a mental representation of that goal being fulfilled). Interestingly, internal goals can be accomplished even in the absence of external signals, for instance when an individual mistakenly believes they have completed a task. Extrinsic regulatory goals can likewise be fulfilled in the absence of cues from an interaction partner. Consider Person B’s goal of using prosocial behaviour (in this case, social support) to reduce Person A’s negative affect. Dozens of studies have documented that merely engaging in a prosocial act produces a form of positive affect, or “warm glow” irrespective of this act’s consequences for others. Person B may interpret this warm glow as an internally generated signal that her prosociality has effectively reduced Person A’s negative affect. Indeed, individuals often believe their prosociality benefits others (and as such, fulfills an extrinsic regulatory goal) more than it actually does, suggesting that Person B’s extrinsic goal can be fulfilled based on her perception that she has effectively altered another person’s action, whether or not this perception is based on feedback from Person A. These response-independent processes can improve Person B’s affective experiences during extrinsic interpersonal regulatory ep isodes (i.e., when she attempts to regulate Person A) but can also operate during very different episodes: in which Person B never intends to regulate Person A’s affect at all. Such cases are worth considering here. A prominent line of reasoning holds that proso cial behavior—although apparently other-oriented—is often driven by purely intrapersonal regulatory goals. For instance, if Person B simply experiences Person A’s distress as a negative stimulus, her subsequent behavior could reflect attempts to make herself (Person B) feel better. Sometimes this requires helping another person, but sometimes it does not. In fact, in some cases Person B, in lieu of acting prosocially, might regulate her emotion by removing herself from the presence of Person A, or psychologically distancing herself from Person A’s distress. In fact, a recent study demonstrated that individual differences in emotion regulation ability track decreased prosocial motivation, likely reflecting effortful reduction of empathy. Critically, this form of regulation—although often a factor in promoting prosocial behaviors—does not meet our cri teria for extrinsic or interpersonal regulation.

A framework for organising past work and posing new questions

Scientists have studied phenomena relevant to interpersonal regulation—including empathy, social support provision, emotion expression, and prosocial behaviour—for the better part of a century, but these lines of work often make surprisingly little contact with each other. Often this is because extant work focuses on only one half of the interpersonal equation: research on social sharing and social support’s effects on well-being, for instance, often focus exclusively on the individual seeking help (here, Person A), whereas research on empathy and prosociality typically consider only the observer (here, Person B). This approach stands in stark contrast to everyday social interactions, which comprise a deep interplay between target and observer, helped and helper. By considering this interplay under a single conceptual framework, we hope to unite these domains and emphasize their parallels. This framework also explains inconsistent effects documented by prior work on interpersonal regulation. For instance, a great deal of work has documented both cases in which sharing emotions with others exerts positive effects on individuals’ affective responses to events, and cases in which sharing has no such effect. A process model of intrinsic interpersonal regulation suggests that such inconsistency could reflect differences between response-dependent and response-independent regulatory mechanisms. If an individual seeks the safety signals afforded by social support, he will require a particular response from the person with whom he shares. If he instead seeks affiliation and contact with others, a less constrained response from (or the mere presence of) others can suffice in regulating his emotion. Finally, if he need only clarify his affective states and their sources through labeling to feel better, then sharing can have salutary “side effects” that are independent of others’ feedback. Similarly, individuals encountering someone else’s emotions often respond prosocially, but the psychological sources of such behavior have remained the topic of an old and vociferous debate. Specifically, whereas Batson typically refers to prosociality as emerging through a fundamen tally other-oriented affective state, Cialdini and others have claimed that, instead, prosociality reflects self-oriented affective goals, such as reducing one’s own negative affect in response to others’ distress. An interpersonal regulatory framework allows us to reframe this debate: an individual’s responses to another person’s distress could represent (a) an extrinsic interpersonal goal to help the distressed other or (b) an intrapersonal goal to feel better one’s self. Emotions often serve as social magnets: drawing us toward others, in search of or desiring to help. Although scientists have examined various social functions of affect for decades, there have been only scarce attempts to combine these insights with contem porary research on emotion regulation. We believe that doing so can provide new clarity and focus to an exciting and growing research domain.

This framework for interpersonal regulation also draws attention to unanswered questions in this budding research domain. One especially interesting growth point is exploration of how individ uals monitor each other’s states and adjust their behavior accord ingly when pursuing interpersonal regulation goals. For instance, in our model, Person A’s expressive behavior serves as an input that initiates Person B’s affective experience. Similarly, Person B’s prosocial behavior serves as an input that can succeed or fail in helping Person A. How do individuals monitor the extent to which their behavior is “getting through” to others (e.g., serving as an efficient affective input for another person)? And how do individuals tune their behavior to improve its fidelity? These questions have yet to be addressed. Doing so may require drawing from domains far afield from typical experimental psychology but will also undoubtedly enrich our understanding of interpersonal regulation in unanticipated ways. A second avenue for future research will be examining the relationship between intra- and interpersonal regulation. As we mentioned above, individuals in social situations likely deploy both forms of regulation concurrently. However, the contextual factors that determine when people deploy intrapersonal versus interpersonal regulatory strategies—and when each class of regu lation is more or less useful—have yet to be systematically ex plored. Finally, although the majority of research used to build the interpersonal regulation framework emerges from social psychol ogy and cognitive neuroscience, this approach can powerfully describe regulation in many other domains. For instance, the formation of attachment relationships during childhood represent a critical early instantiation of interpersonal regulation that can guide individuals’ use of interpersonal regulatory strategies throughout their lives. Similarly, an interpersonal regulatory framework is germane to understanding both psychiatric disorders—which often include abnormalities in interpersonal regulatory mechanisms—and psychotherapy—which often reflects formalized strategies for extrinsic interpersonal regulation and for training patients to better use intrinsic interpersonal regulation. The relevance of interpersonal regulation across disciplinary boundaries highlights the need to continue developing a synthetic, “portable” framework that can describe interpersonal regulatory processes across multiple domains Emotions often serve as social magnets: drawing us toward others, in search of or desiring to help. Although scientists have examined various social functions of affect for decades, there have been only scarce attempts to combine these insights with contem porary research on emotion regulation. We believe that doing so can provide new clarity and focus to an exciting and growing research domain.